To the Editor:

Advancing critical care research is necessary to improve patient outcomes and has been defined as a priority for our healthcare system (1). However, most critically ill patients are initially incapacitated due to their acute illness, and are unable to participate in informed consent for research participation decisions (2). Therefore, surrogates make decisions for patients and often do so without a priori knowledge of the patients’ wishes. The surrogate consent process to enroll critically ill patients into research studies is complex. During the initial consent for a clinical trial, surrogates may also be asked to consent for the collection of biospecimens from the patient, including genetic material. Though consent rates for most genetic studies are generally high, individuals who are able to consent for themselves often have concerns regarding the use of their genetic material (3). In addition, racial and ethnic disparities have been reported in the willingness of individuals to consent to their own participation in genetic studies (4–6). However, whether surrogates are willing to consent for the collection of genetic material from critically ill patients has not been previously determined.

When a surrogate provides consent for a research study, surviving patients who regain decisional capacity should be reconsented for their prior and continued participation. This reconsent process is unique to critical care research, as other incapacitated research participants, such as those with dementia, usually do not regain consent capacity. A better understanding of this reconsent process may provide insight into the patient’s perception of the burden of participating in clinical research. Finally, multicenter clinical trials of critically ill patients are recommended to include assessment of long-term outcomes (LTO) (7). However, it is presently unclear whether critical care survivors are willing to participate in LTO assessments.

Therefore, using 1,164 patients enrolled into three Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network trials (ALTA, OMEGA, and EDEN) (8–10), we sought to better understand the surrogate consent for genetic studies, the reconsent process, and the willingness of critical care survivors to participate in subsequent LTO studies. At the time of consent for these three clinical trials, surrogates were asked to provide consent for the collection of the patient’s genetic material for three types of ancillary studies: (1) genetic studies related to the parent study only (n = 1164), (2) future genetic studies for any acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)-related research (n = 1164), and (3) future genetic studies for non–ARDS-related research (n = 1059). Patient race was categorized as white, African American, other, or not reported. Patient ethnicity was defined as Hispanic or not Hispanic; thus, study patients could be coded as being any race and also Hispanic. When they regained decisional capacity sufficient to provide informed consent, surviving patients underwent reconsent for their study participation. In regard to LTO, surrogates were initially consented for subject participation in assessments at 6 and 12 months after ARDS onset. Patients meeting eligibility criteria and not reconsented by hospital discharge were reconsented for LTO participation when subsequently contacted by telephone. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of abstracts (11, 12).

Overall, surrogates were generally willing to consent to the collection of the patient’s genetic material for all three types of ancillary studies (type 1, 92.0%, 95% CI = 90.3–93.4%; type 2, 90.5%, 95% CI = 88.7–92.1%; and type 3, 84.6%, 95% CI = 82.3–86.7%). However, surrogates were statistically less likely to provide consent for genetic studies when the future use of the material was not related to the parent study or ARDS research in general (P < 0.05). In univariate and multivariate analyses, surrogates of African Americans and other races were less likely to consent for each of the three different genetic studies when compared with surrogates of white patients (Tables 1 and 2). Surrogates of Hispanic patients were less likely to consent for genetic testing related to the parent study and genetic testing for future ARDS research not related to the parent study (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

SURROGATE CONSENT FOR ANCILLARY GENETIC SUBSTUDIES BY PATIENT RACE/ETHNICITY

| Patient | Percentage of Surrogate Approval for Genetic Substudies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Studies for Parent Study Only (n = 1164) | Future Genetic Studies for Any ARDS-related Research (n = 1164) | Future Genetic Studies for Non–ARDS-related Research (n = 1059) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 93.8% [92.2–95.4%] (n = 884) | 92.3% [90.5–94.1%] (n = 884) | 87.6% [85.3–89.9%] (n = 798) |

| African American | 84.8% [79.7–89.9%] (n = 191) | 83.8% [75.6–89.0%] (n = 191) | 79.1% [73.2–85.0%] (n = 182) |

| Other | 81.0% [69.1–92.3%] (n = 42) | 81.0% [69.1–92.3%] (n = 42) | 71.4% [56.4–86.4%] (n = 35) |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 90.5% [85.6–95.4%] (n = 137) | 86.9% [81.3–92.6%] (n = 137) | 74.2% [66.6–81.8%] (n = 128) |

Data in brackets are 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE 2.

SURROGATE CONSENT FOR ANCILLARY GENETIC SUBSTUDIES BY PATIENT RACE/ETHNICITY: MULTIVARIABLE ANALYSES

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic material collection for parent-related studies | ||||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.55 | <0.01 |

| Other | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.64 | <0.01 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.04 |

| Age, yr | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.71 |

| Female | 0.90 | 0.58 | 1.39 | 0.63 |

| Genetic material collection for any ARDS-related research | ||||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.61 | <0.01 |

| Other | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.82 | 0.02 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.02 |

| Age, yr | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.96 |

| Female | 0.97 | 0.64 | 1.45 | 0.87 |

| Genetic material for non–ARDS-related research | ||||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.76 | <0.01 |

| Other | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.76 | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 0.67 | 0.37 | 1.20 | 0.18 |

| Age, yr | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.93 |

| Female | 1.28 | 0.90 | 1.83 | 0.18 |

Definition of abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

All of these analyses were performed using white patients as the referent.

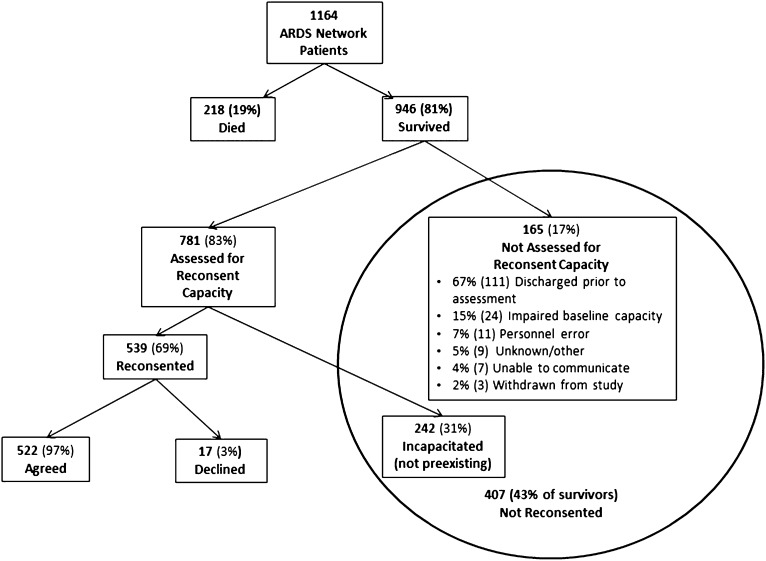

Of the 946 surviving patients, 407 (43%, 95% CI = 40–46%) were not reconsented due to either not being assessed for regaining consent capacity (n = 165) or a perceived lack of decisional capacity upon assessment (n = 242) (Figure 1). Of patients who survived and regained decisional capacity sufficient to provide reconsent, 522 of 539 (97%, 95% CI = 96–98%) affirmed their study participation. A total of 659 surviving patients met eligibility criteria for LTO assessments. The majority, 440 (67%, 95% CI = 63–70%), had provided reconsent for participation prior to hospital discharge. The remaining 219 (33%, 95% CI = 29–37%) were either not assessed for reconsent or lacked reconsent capacity in the hospital. Subsequently, they were consented for LTO assessment at the time of the initial follow-up telephone call conducted as part of the LTO assessment protocol. Overall, 211 of 219 (96%, 95% CI = 93–99%) were willing to consent to ongoing LTO study participation.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the reconsent process.

Optimizing the surrogate consent process for critical care research is imperative to both protect the rights of vulnerable patients and increase study enrollment. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation examining the willingness of surrogates to provide informed consent for the collection of biospecimen samples from critically ill patients. In our study, surrogates were less willing to provide consent for future non–ARDS-related genetic research studies. Patients are generally willing to consent broadly to the use of biospecimens, but desire information regarding the type of research performed on their specimens before providing consent (3, 4). Similarly, our results demonstrate that surrogates are also less willing to provide consent for the collection of genetic material from patients when there is uncertainty regarding the use of the genetic material. Higher rates of study participation from surrogates may occur with enhanced communication concerning the actual use of the biospecimen material. In general, individuals of racial and ethnic minorities are less willing to agree to participate in clinical research studies (3–6). The lower consent rates for genetic studies in surrogates of underrepresented minorities highlights potential concerns regarding cultural differences and disparities in medical research (13, 14). Future prospective studies should examine the role of racial and ethnic disparities of surrogates in providing consent for a critically ill patient’s participation in research.

In 2008, the Office for Human Research Participations Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision Making in Research recommended that incapacitated research participants who are anticipated to regain consent capacity be evaluated for reconsent (15). Our high rates of reconsent may indicate that subjects agreed with their surrogates’ consent decision; however, this would be an oversimplification of a complex consent process. Previous studies have shown that significant discrepancies exist between critically ill patients and their surrogates regarding willingness to participate in hypothetical critical care research studies (16). A complete understanding of the reconsent process is also inherently hampered by the inability to include patients who died before they could be reconsented (i.e., survivorship bias). Furthermore, reconsent rates may be influenced by the magnitude of burden from continued study participation at the time of reconsent. As 43% of the surviving patients were not able to be reconsented, our results raise important concerns about the feasibility of conducting these assessments. To improve the conduct of the reconsent process, specific tools to assess decision-making capacity exist and should be used, and research personnel should be properly trained to reliably conduct competency assessments (17–19). Although obtaining LTO assessments of critical care survivors is important, concerns have been raised regarding feasibility of these studies and cohort retention (20). Our study demonstrates that subjects are willing to be contacted for LTO assessments, and therefore, high rates of cohort retention are possible in studies of critical care survivors. In conclusion, our study begins to examine the nuances of the surrogate consent and reconsent process, and demonstrates the need for future investigation in this area.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants K24-HL-089223 and N01 HR56167 (M.M.) and N01HR56170, R01HL091760, and 3R01HL091760-02S1 (D.M.N.).

Author Contributions: A.S. and M.M.: involvement in conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; and writing the article and substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission. B.T.T.: involvement in design of the study, acquisition of data, and substantial involvement in revision prior to submission. D.M.N. and R.O.H.: involvement in conception and design of the study; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; and substantial involvement in revision prior to submission. A.W.: involvement in data analysis. E.L.B.: involvement in conception, hypothesis delineation, and design of the study and data interpretation.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Luce JM, Cook DJ, Martin TR, Angus DC, Boushey HA, Curtis JR, Heffner JE, Lanken PN, Levy MM, Polite PY, et al. American Thoracic Society. The ethical conduct of clinical research involving critically ill patients in the United States and Canada: principles and recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1375–1384. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-726ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen DT. Why surrogate consent is important: a role for data in refining ethics policy and practice. Neurology. 2008;71:1562–1563. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334763.64570.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon CM, L’heureux J, Murray JC, Winokur P, Weiner G, Newbury E, Shinkunas L, Zimmerman B. Active choice but not too active: public perspectives on biobank consent models. Genet Med. 2011;13:821–831. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821d2f88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sterling R, Henderson GE, Corbie-Smith G. Public willingness to participate in and public opinions about genetic variation research: a review of the literature. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1971–1978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogner HR, Wittink MN, Merz JF, Straton JB, Cronholm PF, Rabins PV, Gallo JJ. Personal characteristics of older primary care patients who provide a buccal swab for apolipoprotein E testing and banking of genetic material: the spectrum study. Community Genet. 2004;7:202–210. doi: 10.1159/000082263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McQuillan GM, Porter KS, Agelli M, Kington R. Consent for genetic research in a general population: the NHANES experience. Genet Med. 2003;5:35–42. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, Curtis JR, Gajic O, Guyatt G, Hall J, Israel E, Jain M, Needham DM, et al. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1121–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthay MA, Brower RG, Carson S, Douglas IS, Eisner M, Hite D, Holets S, Kallet RH, Liu KD, MacIntyre N, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an aerosolized β2 agonist for treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:561–568. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2090OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, deBoisblanc BP, Steingrub J, Rock P NIH NHLBI Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network of Investigators. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA. 2011;306:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Steingrub J, Hite RD, Moss M, Morris A, Dong N, Rock P National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:795–803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smart A, Mealer M, Moss M. Understanding the re-consent process for critical care research: results of an observational study and national survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A3884. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smart A, Thompson BT, Clark BJ, Macht M, Benson AB, Burnham EL, Moss M. Surrogate informed consent for genetic studies in ARDS Network trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A4448. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankar P, Cho MK, Condit CM, Hunt LM, Koenig B, Marshall P, Lee SS, Spicer P. Genetic research and health disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2985–2989. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seto B. History of medical ethics and perspectives on disparities in minority recruitment and involvement in health research. Am J Med Sci. 2001;322:248–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Secretary's Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP), US Department of Health and Human ServicesRecommendations from the Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision Making in Research (SIIIDR). 2008. [updated 2009, accessed 2013]. Available from:http:www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/20090715letterattach.html

- 16.Newman JT, Smart A, Reese TR, Williams A, Moss M. Surrogate and patient discrepancy regarding consent for critical care research. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2590–2594. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318258ff19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, Golshan S, Glorioso D, Dunn LB, Kim K, Meeks T, Kraemer HC. A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:966–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, Singer PA, McKenny J, Naglie G, Katz M, Guyatt GH, Molloy DW, Strang D. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:27–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan E, Shahid S, Kondreddi VP, Bienvenu OJ, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Informed consent in the critically ill: a two-step approach incorporating delirium screening. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:94–99. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295308.29870.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubenfeld GD, Angus DC, Pinsky MR, Curtis JR, Connors AF, Jr, Bernard GR. Outcomes research in critical care: results of the American Thoracic Society Critical Care Assembly Workshop on Outcomes Research. The Members of the Outcomes Research Workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:358–367. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9807118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]