To the Editor:

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, granulomatous disease of unknown cause that most commonly affects young adults, particularly black females (1). Recent studies indicate that sarcoidosis-related mortality is on the rise, perhaps relating to improved disease detection (2). Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is the second-leading cause of death, and young adults are particularly at risk (3). CS is commonly missed during routine clinical screening, including history, exam, and electrocardiography (4), and most cases are detected for the first time during autopsy (5, 6). Although no reference standard exists for the diagnosis of CS, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is emerging as the preferred diagnostic modality (7, 8). Despite excellent spatial resolution, CMR with LGE as the sole means of detecting CS may be insufficient (9, 10) as it readily detects nonviable myocardium (11) but is less sensitive to inflamed but viable myocardial tissue that commonly occurs in the early and potentially reversible stages of CS (12). We have shown that CMR with T2 mapping improves the detection of active myocarditis compared with LGE alone (13). Given that active CS is an inflammatory condition, we hypothesized that (1) T2 mapping demonstrates quantitative abnormalities in the myocardium of patients with sarcoidosis compared with controls and (2) myocardial T2 provides complementary myocardial characterization relative to LGE, which together likely form the myocardial substrate for conduction system disease and cardiac arrhythmias.

With local Institutional Review Board approval, we conducted a retrospective study of 50 consecutive subjects with histologically proven sarcoidosis who had undergone CMR for suspected CS between 2010 and 2013. We used established criteria to screen for CS, including an appropriate history (e.g., palpitations, syncope or near syncope, and heart failure symptoms), cardiac exam, and ECG (14). Additional testing (transthoracic echocardiography, Holter monitoring, and electrophysiologic [EP] study) was performed as clinically indicated. Results of clinically acquired ECG, Holter monitoring, and invasive EP testing were recorded along with patient demographics and medications at time of CMR examination, as shown in Table 1. The vast majority (94%) had pulmonary involvement and 30% had skin involvement. Thirty patients (60%) were on oral steroids or immunosuppressive therapy at the time of CMR examination. Fifty-five percent of the patients in this cohort had documented atrial arrhythmia, ventricular arrhythmia, atrioventricular block, or QRS complex duration > 120 ms, collectively termed “significant ECG/EP abnormalities.”

Table 1:

Characteristics of Study Population (N = 50)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 48.6 ± 11.9 |

| Female, n (%) | 26 (52) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 27 (54%) |

| Black | 22 (44%) |

| Other | 1 (2%) |

| LVEF, %, median (IQR) | 60.0 (56.0–66.0) |

| Subjects with LVEF > 50%, n (%) | 40 (80%) |

Definition of abbreviation: LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction.

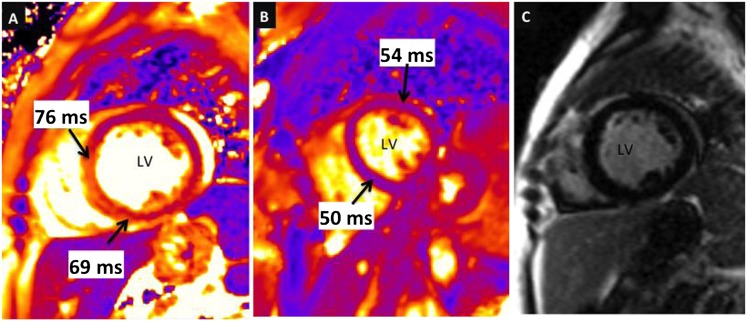

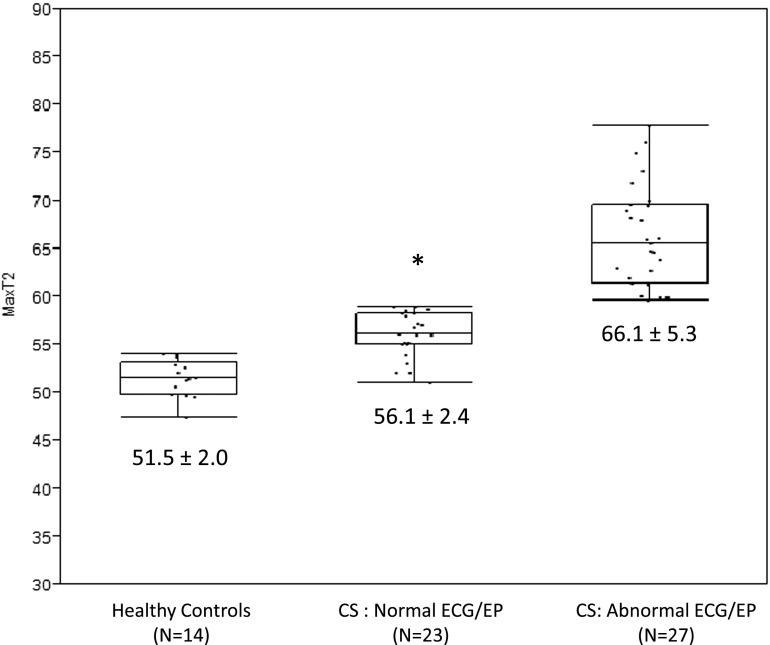

CMR examinations were performed on the identical 1.5 T scanner (MAGNETOM Avanto, Siemens Medical Solutions, Inc., Erlangen, Germany) to detect myocardial LGE and T2 changes using established protocols (15). Standard left ventricular myocardial segments (16) were rated by expert reviewers for presence/absence of LGE positivity, and maximum myocardial T2 was recorded for each exam. Maximum myocardial T2 exceeding 59 milliseconds was used to indicate abnormal T2 based on established values derived from patients with acute myocarditis (13), as demonstrated in Figure 1. Among the 14 control subjects (no known chronic or acute disease), none had elevated T2 above the established threshold (59 ms), and all were LGE negative. Twenty-seven patients (54%) had significantly elevated myocardial T2 compared with healthy control subjects (60.0 [56.8–65.9] ms, vs. 51.5 [50.0–52.9] ms, P < 0.0001). The prevalence of abnormal T2 was not significantly higher (54%) than the prevalence of LGE positivity in this cohort (45%, P = 0.3458). However, 11 of 27 (41%) LGE-negative patients showed T2 abnormality (e.g., Figure 1) and 7 of 23 normal T2 patients were LGE positive, suggesting complementary information to detect CS from both techniques. Patients with versus those without significant ECG abnormalities had higher myocardial T2 values (62.9 [58.6–68.9] ms vs. 58.3 [55.0–61.3] ms, P = 0.0109) as well as a greater prevalence of myocardial injury by LGE (62% vs. 26%, P = 0.0128) (Figure 2). Finally, there were no statistical differences in CMR manifestations (T2 or LGE) observed between black and white patients with CS (Table 2).

Figure 1.

(A, B) T2 maps and sample T2 values of the left ventricle (LV) in cross-section are shown in a patient with sarcoidosis (A) in comparison to a healthy control subject (B). Note the considerably higher myocardial T2 values in the patient with sarcoidosis. (C) A late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) image acquired in the same sarcoidosis patient shows no evident hyperenhancement (i.e., LGE was negative despite markedly abnormal T2).

Figure 2.

Box plots of myocardial T2 values in healthy control subjects, patients with cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) without significant abnormalities by ECG or invasive electrophysiologic testing (EP), and patients with sarcoidosis with significant ECG or EP abnormalities. Patients with sarcoidosis with normal ECG and EP results had significantly higher myocardial T2 values than healthy controls, and had significantly lower myocardial T2 values compared with sarcoidosis patients with significant ECG or EP abnormalities (*P ≤ 0.01 for both comparisons).

Table 2:

Comparison of CMR Characteristics According to Race

| Prevalence | White (n = 27) | African American (n = 22) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal T2 | 48.15% | 63.64% | 0.278 |

| Abnormal LGE | 51.85% | 33.33% | 0.199 |

| Either abnormal T2 or abnormal LGE or both | 70.37% | 63.64% | 0.617 |

| ICD | 18.52% | 22.73% | 0.716 |

Definition of abbreviations: CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; ICD = implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement.

Pearson’s chi-squared test.

To predict significant ECG/EP abnormalities, the logistic regression model using both T2 abnormality and LGE positivity was preferable with the smallest Akaike information criterion (AIC = 63.745), as compared with the model with a single predictor using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test assuming non–normally distributed data (AIC = 66.536 and 65.376 for T2 abnormality and LGE positivity, respectively). Similarly, the prediction model for whether or not the patient had a defibrillator implanted using both T2 abnormality and LGE positivity outperformed the models with either one alone (AIC = 47.303 for the combined model compared with 51.962 and 48.026 for the single-predictor models).

This study confirms our hypothesis that myocardial T2 signal is commonly elevated in patients with sarcoidosis and suspected CS. The clinical implications of abnormal myocardial T2 signals in the context of cardiac disease remain unclear, but are believed to reflect potentially reversible pathology. In contrast to LGE, which typically detects nonviable (e.g., fibrotic or necrotic) tissue, T2 signal arises from changes in free water within the tissues, as occurs in the setting of acidosis, edema, or inflammation (17). Myocardium exhibiting elevated T2 signal is not only viable but may retain normal contractile function (13), as was frequently the case in this study. In the context of sarcoidosis, T2 is presumed to reflect active granulomatous inflammation, which is potentially reversible with appropriate treatment (18). At present, the natural history of T2 abnormalities is unclear; however, this study indicates that T2 abnormalities do correspond to clinically relevant electrocardiographic and EP abnormalities. It is logical to speculate that the T2 abnormalities could progress to irreversible fibrosis and attendant alterations in myocardial function with increased risk of malignant cardiac arrhythmias. If so, the T2 signal could represent an early disease manifestation that is potentially reversible.

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography ([18F]FDG-PET CT) is another option for the detection of CS, and is shown to be comparable to conventional CMR with LGE for the detection of CS in some studies. However, there are certain technical limitations of [18F]FDG-PET CT (e.g., relating to blood glucose/insulin levels), and risks (radiation exposure) attendant to its use. Likewise, CMR is not feasible in those with ferromagnetic or active implants (e.g., shrapnel, implantable cardioverter defibrillator). The uptake of [18F]FDG corresponds with metabolically active tissue, including active immune (e.g., granulomas) or malignant cells. When compared head-to-head, and presuming that the studies were performed by specialists equally competent in performing CMR and [18F]FDG-PET CT, CMR with LGE corresponds better with actual clinical disease manifestations (e.g., electrocardiography) than does FDG-PET (7) and is shown to have higher specificity (19). LGE-CMR has undergone extensive histopathological correlation as a reliable indicator of myocardial injury as well as scar. Although CMR was not compared with [18F]FDG-PET CT in our analysis, it is evident that CMR/LGE combined with T2 mapping is superior for the detection of CS compared with CMR/ LGE alone. Furthermore, CMR with LGE and T2 mapping has the advantage of detecting myocardial damage that is either irreversible (scarred) or reversible (inflamed). As we also showed that this approach improves the detection of myocardial substrate for electrocardiographic abnormalities and arrhythmias, complementary myocardial characterization with T2 and LGE CMR can not only detect clinically relevant disease but also serve as a useful biomarker for response to novel therapies.

In conclusion, myocardial T2 is quantitatively abnormal in patients with sarcoidosis, and the inclusion of abnormal T2 complements that of LGE abnormality for the detection of CS. Furthermore, T2 elevation in conjunction with LGE better predicts electrocardiographic abnormalities and arrhythmias compared with either technique alone. These findings suggest that a comprehensive CMR approach that includes both T2 and LGE is best suited to identify clinically relevant disease activity. Further prospective studies are warranted using myocardial T2 as a tool for guiding decisions relating to medical and device (e.g., implantable cardioverter defibrillator) therapies.

Footnotes

Supported in part by NIH grant R01HL116533.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to this work via (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391–399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erdal BS, Clymer BD, Yildiz VO, Julian MW, Crouser ED. Unexpectedly high prevalence of sarcoidosis in a representative U.S. Metropolitan population. Respir Med. 2012;106:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swigris JJ, Olson AL, Huie TJ, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, Sprunger D, Brown KK. Sarcoidosis-related mortality in the United States from 1988 to 2007. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1524–1530. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1679OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubrey SW, Falk RH. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;52:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabre A, Sheppard MN. Sudden adult death syndrome and other non-ischaemic causes of sudden cardiac death. Heart. 2006;92:316–320. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.045518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomsen TK, Eriksson T. Myocardial sarcoidosis in forensic medicine. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1999;20:52–56. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199903000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman AM, Curran-Everett D, Weinberger HD, Fenster BE, Buckner JK, Gottschall EB, Sauer WH, Maier LA, Hamzeh NY. Predictors of cardiac sarcoidosis using commonly available cardiac studies. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel MR, Cawley PJ, Heitner JF, Klem I, Parker MA, Jaroudi WA, Meine TJ, White JB, Elliott MD, Kim HW, et al. Detection of myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis. Circulation. 2009;120:1969–1977. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen F, Pehrsson SK, Hammar N, Sköld CM, Izumi T, Nagai S, Shigematsu M, Eklund A. ECG-abnormalities in Japanese and Swedish patients with sarcoidosis: a comparison. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2001;18:284–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, van Geuns RJ, Dassen WR, Gorgels AP, Crijns HJ. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vöhringer M, Mahrholdt H, Yilmaz A, Sechtem U. Significance of late gadolinium enhancement in cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) Herz. 2007;32:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s00059-007-2972-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamagishi H, Shirai N, Takagi M, Yoshiyama M, Akioka K, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J. Identification of cardiac sarcoidosis with (13)N-NH(3)/(18)F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1030–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thavendiranathan P, Walls M, Giri S, Verhaert D, Rajagopalan S, Moore S, Simonetti OP, Raman SV. Improved detection of myocardial involvement in acute inflammatory cardiomyopathies using T2 mapping. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:102–110. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.967836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giri S, Shah S, Xue H, Chung YC, Pennell ML, Guehring J, Zuehlsdorff S, Raman SV, Simonetti OP. Myocardial T₂ mapping with respiratory navigator and automatic nonrigid motion correction. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:1570–1578. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial Segmentation and Registration for Cardiac Imaging. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eitel I, Friedrich MG. T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute cardiac disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:13. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Safka K, Graham JJ, Roifman I, Zia MI, Wright GA, Balter M, Dick AJ, Connelly KA. Correlation of late gadolinium enhancement MRI and quantitative T2 measurement in cardiac sarcoidosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. (In press) doi: 10.1002/jmri.24196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohira H, Tsujino I, Ishimaru S, Oyama N, Takei T, Tsukamoto E, Miura M, Sakaue S, Tamaki N, Nishimura M. Myocardial imaging with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:933–941. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]