Summary

Background

Depression is common and is associated with poor outcomes among elderly care-home residents. Exercise is a promising low-risk intervention for depression in this population. We tested the hypothesis that a moderate intensity exercise programme would reduce the burden of depressive symptoms in residents of care homes.

Methods

We did a cluster-randomised controlled trial in care homes in two regions in England; northeast London, and Coventry and Warwickshire. Residents aged 65 years or older were eligible for inclusion. A statistician independent of the study randomised each home (1 to 1·5 ratio, stratified by location, minimised by type of home provider [local authority, voluntary, private and care home, private and nursing home] and size of home [<32 or ≥32 residents]) into intervention and control groups. The intervention package included depression awareness training for care-home staff, 45 min physiotherapist-led group exercise sessions for residents (delivered twice weekly), and a whole home component designed to encourage more physical activity in daily life. The control consisted of only the depression awareness training. Researchers collecting follow-up data from individual participants and the participants themselves were inevitably aware of home randomisation because of the physiotherapists' activities within the home. A researcher masked to study allocation coded NHS routine data. The primary outcome was number of depressive symptoms on the geriatric depression scale-15 (GDS-15). Follow-up was for 12 months. This trial is registered with ISRCTN Register, number ISRCTN43769277.

Findings

Care homes were randomised between Dec 15, 2008, and April 9, 2010. At randomisation, 891 individuals in 78 care homes (35 intervention, 43 control) had provided baseline data. We delivered 3191 group exercise sessions attended on average by five study participants and five non-study residents. Of residents with a GDS-15 score, 374 of 765 (49%) were depressed at baseline; 484 of 765 (63%) provided 12 month follow-up scores. Overall the GDS-15 score was 0·13 (95% CI −0·33 to 0·60) points higher (worse) at 12 months for the intervention group compared with the control group. Among residents depressed at baseline, GDS-15 score was 0·22 (95% CI −0·52 to 0·95) points higher at 6 months in the intervention group than in the control group. In an end of study cross-sectional analysis, including 132 additional residents joining after randomisation, the odds of being depressed were 0·76 (95% CI 0·53 to 1·09) for the intervention group compared with the control group.

Interpretation

This moderately intense exercise programme did not reduce depressive symptoms in residents of care homes. In this frail population, alternative strategies to manage psychological symptoms are required.

Funding

National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment.

Introduction

A growing number of elderly people (ie, older than 65 years) live in residential accommodation, which offers assistance with personal, and in some cases nursing, care. Clinically significant depression is very common among residents of care homes1 and is associated with poor outcomes, including frailty and increased mortality.2 Exercise is a promising, low-risk intervention that might be helpful in prevention and treatment of depression in this group.3–5 We describe a cluster randomised trial to test the hypothesis that a moderate intensity exercise programme would reduce the burden of depressive symptoms in residents of care homes.

Methods

Study design and participants

Full details of the trial methods and conduct are available elsewhere;6–8 they are briefly summarised here. We approached all care homes with between 16 and 70 beds in two locations in the UK; Coventry and Warwickshire, and northeast London. Care homes were excluded when fewer than six residents were likely to take part in the study, or when most residents either had severe cognitive impairment or were non-English speaking.

Once care homes had agreed to participate, we invited residents to give written, informed consent, or if they lacked capacity to consent, for their next of kin to give written, informed agreement for us to collect data directly from participants, from care-home staff, and from care-home and National Health Service (NHS) records. We included English speaking, permanent residents, aged 65 years or older. We excluded residents who were too ill to approach at the time of recruitment visits or who had severe communication problems, those with a terminal illness, and those whom the care-home manager believed it was inappropriate to approach at the time of recruitment (eg, when a resident had a recent bereavement). We provided participant information sheets in larger print and audio format for residents with poor eyesight. The recruitment team, who were all nurses or physiotherapists with experience of working with elderly people, received additional training from the study ethicist in the assessment of capacity to consent to this research. To help maximise completion of patient-reported outcomes these instruments were administered orally; the primary outcome was always completed first. When a resident was unable or unwilling to provide outcome data a further attempt was made to collect data on a subsequent visit to the home. We included all residents in the intervention activities except those who had difficulty sitting, or were breathless at rest. We recruited additional participants for 9 months after randomisation for an end of study cross-sectional analysis, using the same criteria as described previously. Ethical review for the study was provided by the Joint University College London/University College London Hospital Committees on the Ethics of Human Research (Committee A).

Randomisation and masking

A statistician independent of the study randomised each home, immediately after baseline data collection in that home. We used a 1 to 1·5 randomisation to reduce intervention costs. Care homes were first stratified by location and then minimised into intervention and control groups by type of home provider (local authority, voluntary, private and care home, private and nursing home) and size of home (<32 or ≥32 residents). Researchers collecting follow-up data from individual participants, and the participants themselves, were inevitably aware of home randomisation because of the physiotherapists' activities within the home. A researcher masked to study allocation coded NHS routine data; however, because of the unbalanced randomisation we were not able to mask the researchers doing the final statistical analyses to assignments.

Procedures

For the control home, we delivered one session of training in depression awareness to staff, ensuring that they were aware of present best care for the identification and management of depression in this population, including encouraging discussion of depression, increasing activities (eg, playing games with group interaction), and referral to primary or secondary care when needed.

For the intervention group, we developed a package that included the depression awareness training, group exercise sessions, and a whole home component. Development of the active interventions was informed by physiotherapy and organisational change literature along with empirical data from two systematic reviews.3,5,8 Physiotherapists delivered all elements of the programme. Care-home staff were informed about individualised mobility assessments and exercise prescriptions for each of the residents to encourage an increase in residents' physical activity. We delivered exercise in groups to enhance adherence, increase social interaction, and reduce the cost per resident.9,10 The exercise classes were designed to provide a moderate intensity strength and aerobic training stimulus.8 The twice-weekly physiotherapist-led 45 min sessions ran for up to 12 months (intended length 12 months, no minimum duration) in each home and provided a moderately intense exercise stimulus via progressive aerobic and resistance training activities to be done while sitting and standing, using simple, accessible exercise equipment supported by music tracks selected for their facilitatory effects.11 As part of the whole home approach the physiotherapists also engaged the care-home staff and managers in encouraging residents to be more physically active in their daily lives.

Our primary outcome was the geriatric depression scale-15 (GDS-15), which was developed and validated for measurement of depressive symptoms among elderly people.12 We defined depression as having five or more depressive symptoms on GDS-15 or equivalent for those with 10–14 responses (five positive responses when 13 or more items completed, four positive responses when 11 or 12 items completed, and three positive responses when 10 items completed; nine or fewer items completed was deemed missing data). This approach seems to give the best sensitivity and specificity for presence or absence of depressive mood.13 Our three coprimary analyses were: cohort analysis—number of depressive symptoms 12 months after randomisation in those recruited before randomisation; depressed cohort analysis—number of depressive symptoms 6 months after randomisation in those recruited before randomisation and depressed at baseline; and cross-sectional analysis—prevalence of depression among all participants resident in a study home at 12 months.

Our cohort analyses included only study participants present at randomisation. We report these analyses for all participants, and separately for those with depression, because we were testing a whole home intervention whose effects—positive or negative—could affect all residents, not only those with depression at baseline. We included residents recruited after care homes were randomised for our end-of-study cross-sectional analyses to ensure that we could estimate the long-term effects of our intervention on the prevalence of depression in participating care homes rather than only its effect on relatively healthy cohort survivors.

Study researchers measured cognitive function using the mini-mental state examination (MMSE14), quality of life using the European quality of life-5 dimensions instrument (EQ-5D15), and fear of falling using a yes or no question, present level of pain on a five point ordinal scale conditional on the EQ-5D pain question, and used the short physical performance battery (SPPB) to measure functional performance (assessment data).16 The resident's main carer, or home manager, completed a proxy EQ-5D, Barthel index, and social engagement scale (proxy data).15–18 Researchers also collected data for comorbidities, length of residence, present medication, and demographic data from care-home records (care-home data). We collected data for peripheral fractures and deaths from care-home and NHS records. We defined an adverse event occurring during the exercise groups or study assessments as one that required external medical attention as a consequence of participation in the study.

Cohort participants completed the same questionnaire instruments at baseline, and 6 and 12 months. We repeated the SPPB at 12 months. We collected care-home and proxy data (drug use over preceding week, proxy EQ-5D, and social engagement scale) 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after the home was randomised.

Statistical analysis

To show an increase in the rate of remission of depression after 6 months from 25% to 40% in the depressed cohort, with 80% power at the 5% significance level, using a 1 to 1·5 randomisation, requires data for 343 participants. Assuming 32 residents per home, a 50% recruitment rate, 40% prevalence of depression, and 15% loss to follow-up at 6 months the average cluster size would be 5·44. We inflated the sample size by 1·22 to allow for an intracluster correlation (ICC) coefficient of 0·05. We aimed to recruit 1232 (∼[343 × 1·22] / [0·4 × 0·85]) participants from 77 homes.

Examination of baseline data after randomisation of 47 homes showed that maintenance of our original recruitment target gave insufficient power for the outcome of remission from depression at 6 months. With the agreement of the trial steering committee, data monitoring ethics committee, and funder, we replaced this outcome with mean difference in number of depressive symptoms on the GDS-15 at 6 months as our primary outcome for the depressed cohort. We set the clinically important difference in the GDS-15 as 1·2 points on the basis of established data.19 Keeping our original recruitment target (77 homes) provided ample statistical power for all three coprimary analyses.

For cohort analyses we included residents in the home from which they were recruited. For cross-sectional analyses we included residents in the home in which they were resident at the end of the study. To avoid obtaining biased estimates in the presence of missing data, we used mixed models to account for clustering, instead of the generalised estimating equations specified in the published protocol.7,20 All analyses were done with Stata (version 11), using the xtmixed command to fit linear mixed models for continuous outcomes and the xtmelogit command to fit logistic mixed models for binary outcomes, with the exception of ordinal and count outcomes, for which SAS (version 9.2) proc glimmix was used. All models included the prespecified covariates of: location, type of home provider, size of home, proportion of residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment in the home at baseline (except when the MMSE was the outcome), sex, age at time of analysis, on antidepressants at baseline, SPPB at baseline (except when proxy EQ-5D or social engagement was the outcome), mean baseline level of outcome (cohort analyses), or mean baseline level of outcome in the home (cross-sectional analysis), and included a random intercept for home. In a sensitivity analysis we did multilevel multiple imputation of the primary outcomes.21 For the purposes of measuring dose received we predefined that attendance equivalent to one group per week would be classed as a minmum dose. This trial is registered with ISRCTN Register, number ISRCTN43769277.

Role of the funding source

A funder's brief informed the development of this study. They had no role in the detailed design of the study; data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

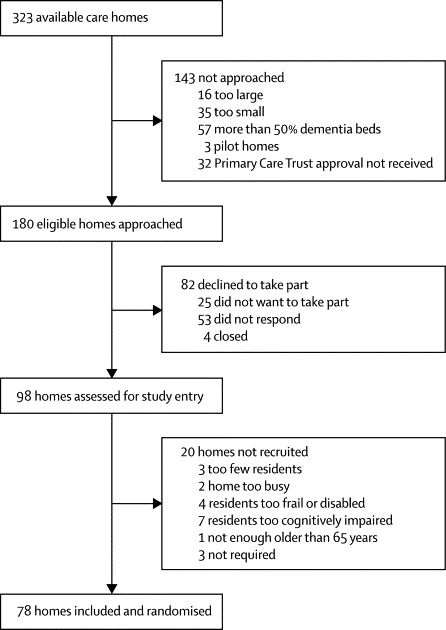

Care homes were randomised between Dec 15, 2008, and April 9, 2010; follow-up was completed 1 year later. 35 homes were assigned to intervention and 43 to control (1 to 1·2 ratio; figure 1, table 1). The final allocation ratio of 1 to 1·2 was less than the 1 to 1·5 planned, but lies within bounds of chance.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of care homes

Table 1.

Cluster (care home) characteristics

| All care homes* |

Study care homes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Intervention | Control | |||

| Number | 323 | 78 | 35 | 43 | |

| Type† | |||||

| Nursing | 81 (25%) | 18 (23%) | 9 (26%) | 9 (21%) | |

| Residential | 242 (75%) | 60 (77%) | 26 (74%) | 34 (79%) | |

| Ownership | |||||

| Private | 262 (81%) | 61 (78%) | 28 (80%) | 33 (77%) | |

| Voluntary or charity | 36 (11%) | 16 (21%) | 7 (20%) | 9 (21%) | |

| Local authority | 25 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Size | |||||

| <32 beds | 158 | 43 | 20 | 23 | |

| ≥32 beds | 165 | 35 | 15 | 20 | |

| Mean number of beds (SD) | 34·89 (19·62) | 31·41 (11·49) | 31·54 (12·15) | 31·30 (11·08) | |

| Median cohort participants per home (IQR) | .. | 11 (8–15) | 11 (7–15) | 11 (9–15) | |

Data are n or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

All care homes registered on the Care Quality Commission website within the two geographical regions of the trial (northeast London, and Coventry and Warwickshire) during development of the trial (in 2008).

Minimisation factors were type of home (local authority, voluntary, private and care home, private and nursing home) and size of home (32 beds or fewer, or more than 32 beds).

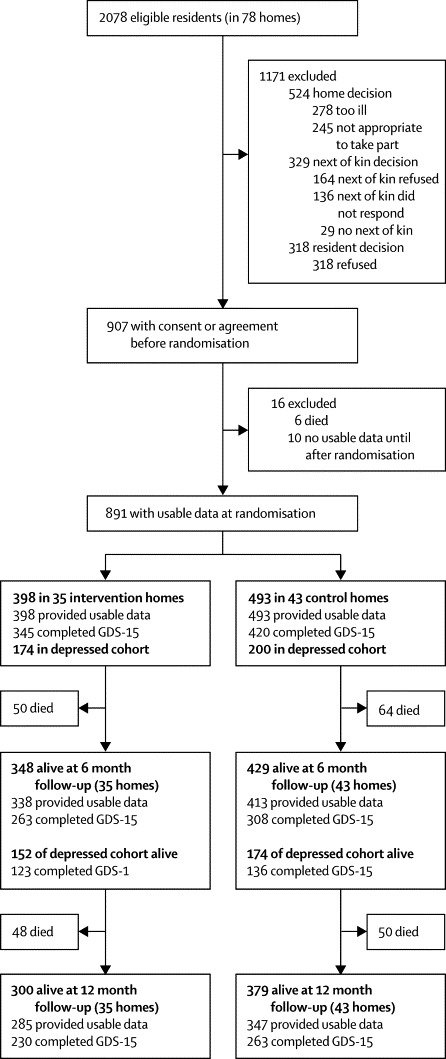

We initially obtained consent or agreement to collect data from 907 (44%) of the 2078 eligible residents; for 50 of 907 (6%) we could only collect proxy, care home, and NHS data. Before randomisation we obtained baseline data from 891 participants (figure 2; table 2). We obtained baseline assessment data from 781 of 891 (88%) residents; 765 of 781 (98%) of whom provided a GDS-15 score. We obtained baseline proxy EQ-5D data for 776 of 891 (87%) residents and drug data for 869 of 891 (98%). The sample were old (mean 86·5 years, range 65–107), predominantly (76%) women, with several comorbidities (tables 2, 3). Baseline characteristics were similar in intervention and control groups (tables 2, 3).

Figure 2.

Recruitment and follow-up of cohort participants

GDS-15=geriatric depression scale 15.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of all cohort participants (N=891)

|

Intervention |

Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Demographic data | |||||||

| Women | 398 | 294 (74%) | .. | 493 | 383 (78%) | .. | |

| White | 393 | 385 (98%) | .. | 488 | 480 (98%) | .. | |

| Taking antidepressants | 397 | 110 (28%) | .. | 490 | 156 (32%) | .. | |

| Age at baseline (years) | 396 | .. | 86·7 (7·2) | 490 | .. | 86·3 (7·5) | |

| Age when left full-time education (years) | 304 | .. | 15·0 (1·8) | 348 | .. | 14·9 (1·9) | |

| Years in home | 392 | .. | 2·4 (2·6) | 488 | .. | 2·5 (2·6) | |

| Assessment data | |||||||

| Depressed (GDS-15 ≥5 or equivalent)* | 345 | 174 (50%) | .. | 420 | 200 (48%) | .. | |

| GDS-15 score (0–15, 0=best) | 345 | .. | 4·8 (3·3) | 420 | .. | 4·8 (3·3) | |

| MMSE score (0–30, 30=best) | 346 | .. | 18·7 (6·9) | 404 | .. | 18·1 (6·6) | |

| SPPB score (0–12, 12=best) | 348 | .. | 1·9 (2·2) | 413 | .. | 1·8 (2·0 | |

| EQ-5D score (−0·594 to 1, 1=best) | 297 | .. | 0·54 (0·39) | 335 | .. | 0·59 (0·37) | |

| Pain today | |||||||

| None | 335 | 221 (66%) | .. | 397 | 264 (66%) | .. | |

| Mild-moderate | 335 | 107 (32%) | .. | 397 | 116 (29%) | .. | |

| Severe | 335 | 7 (2%) | .. | 397 | 17 4% | .. | |

| Fear of falling | 341 | 141 (41%) | .. | 405 | 189 47% | .. | |

| Proxy data | |||||||

| Social engagement | |||||||

| High | 342 | 211 (62%) | .. | 435 | 259 (60%) | .. | |

| Medium | 342 | 97 (28%) | .. | 435 | 133 (31%) | .. | |

| Low | 342 | 34 (10%) | .. | 435 | 43 (10%) | .. | |

| Barthel index (0–100, 100=best) | 337 | .. | 54·5 (29·4) | 417 | .. | 54·0 (27·8) | |

| Proxy EQ-5D (−0·594 to 1, 1=best) | 345 | .. | 0·44 (0·35) | 431 | .. | 0·46 (0·34) | |

| Comorbidities recorded in care-home records | |||||||

| Cancer | 389 | 28 (7%) | .. | 485 | 40 (8%) | .. | |

| Stroke | 392 | 97 (25%) | .. | 488 | 109 (22%) | .. | |

| Dementia | 393 | 113 (29%) | .. | 488 | 134 (27%) | .. | |

| Depression | 392 | 84 (21%) | .. | 486 | 96 (20%) | .. | |

| Anxiety | 391 | 67 (17%) | .. | 485 | 84 (17%) | .. | |

| Osteoporosis | 392 | 45 (11%) | .. | 486 | 50 (10%) | .. | |

| Chronic lung disease | 391 | 47 (12%) | .. | 489 | 56 (11%) | .. | |

| Urinary incontinence | 393 | 214 (54%) | .. | 489 | 286 (58%) | .. | |

GDS-15=geriatric depression scale 15. MMSE=mini-mental state examination. SPPB=short physical performance battery. EQ-5D=European quality of life-5 dimensions.

When fewer than 15 items on the GDS were completed, we deemed depression to be five positive responses when 13 or more items were completed, four positive responses when 11 or 12 items were completed, and three positive responses when 10 items were completed; nine or fewer items completed was deemed missing data.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of all cross-sectional participants (N=751)*

|

Intervention |

Control |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | |

| Women | 355 | 266 (75%) | .. | 396 | 313 (79%) | .. |

| White | 353 | 344 (97%) | .. | 392 | 384 (98%) | .. |

| Age at time of recruitment (years) | 355 | .. | 86·5 (7·6) | 394 | .. | 86·0 (7·7) |

| Age when left full-time education (years) | 283 | .. | 14·9 (1·8) | 284 | .. | 15·0 (1·8) |

| Years in home | 302 | .. | 2·5 (2·8) | 353 | .. | 2·4 (2·7) |

751 of 775 residents provided usable outcome data; for this comparison, intervention and control defined by the homes residents were in at 12 month follow-up.

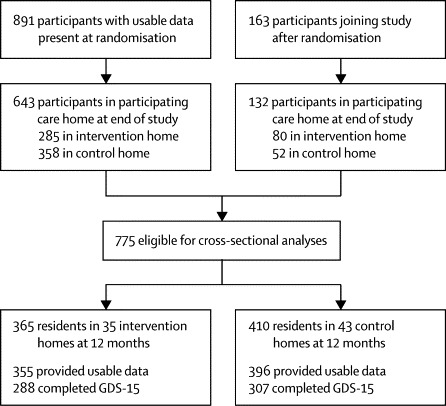

In intervention homes, 80 of 365 (22%) of those in the cross-sectional analysis were recruited after randomisation; in control homes this proportion was 52 of 410 (13%; table 3). The baseline characteristics of participants recruited after randomisation were much the same as those of participants recruited before randomisation and were much the same in both intervention and control groups (appendix pp 3, 5).

In the control homes 496 of 1126 (44%) staff attended depression awareness training. In the intervention homes at least 406 of 884 (46%) staff attended depression awareness and activity training (one training register is missing). One home did not receive the active intervention because residents were too disabled to participate. We delivered 3191 exercise sessions, open to both study participants and non-study participants, in 34 homes; 90% of our target of 92 sets of sessions per home (some larger homes ran several sets of sessions). There were 31 705 individual attendances. On average 9·9 residents attended each session; 5·3 (53%) of whom were trial participants. The median number of sessions attended by study participants in the intervention homes contributing to the 12 month overall cohort analysis was 53 (IQR 15–69), 114 of 224 (51%) achieved the intended minimum dose of 51 attendances (one per working week) or more. Residents with depression at baseline were less likely than those without depression to achieve the minimum intended dose (40 of 99 [40%] vs 74 of 125 [59%]).

No care homes dropped out. In view of the poor state of health of our participants, we achieved very good follow-up rates for the GDS-15; 493 of 679 (73%) in survivors in the cohort analysis at 12 months and 259 of 326 (79%) in survivors in the depressed cohort analysis at 6 months. We collected slightly more outcomes in intervention homes than control homes; of participants who were alive at 12 months we collected GDS-15 data for 230 of 300 (77%) in intervention homes and 263 of 379 (69%) in control homes. The equivalent proportions for the proxy EQ-5D were 272 of 300 (91%) and 327 of 379 (86%). For the cross-sectional analysis we obtained GDS-15 score from 595 of 775 (77%) participants and care-home data for 724 of 775 (93%) participants (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Recruitment and follow-up of cross-sectional participants

GDS-15=geriatric depression scale 15.

We identified no statistically significant, or clinically important, between-group differences in the GDS-15 score. In the overall cohort analysis, at 12 months, the adjusted mean difference in GDS-15 scores was 0·13 points (95% CI −0·33 to 0·60, p=0·5758; ie, control group slightly less depressed). The GDS-15 scores at 12 months were much the same as baseline values in both groups (table 4). In the depressed-cohort analysis the adjusted mean difference in GDS scores was 0·22 (95% CI −0·52 to 0·95, p=0·5662). The GDS-15 scores decreased by a small amount—about one point—in both groups between baseline and 6 months (table 4). In the end of study cross-sectional analysis 124 of 288 (43%) participants in the intervention group and 149 of 307 (49%) participants in the control group were depressed. The odds ratio for depression (intervention: control) was 0·76 (95% CI 0·53–1·09, p=0·1304; table 4).

Table 4.

Effect estimates from multivariable models for three coprimary GDS-15 outcomes

|

Intervention |

Control |

Mean difference (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ICC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 0 months | 6 months | 12 months | N | 0 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||||

| GDS-15 score at 12 months | 224 | 4·5 (3·2) | .. | 4·6 (3·3) | 260 | 4·7 (3·2) | .. | 4·6 (3·3) | 0·13* (−0·33 to 0·60) | .. | 0·00 |

| GDS-15 score at 6 months, in residents who were depressed at baseline | 123 | 7·3 (2·2) | 6·3 (3·1) | .. | 136 | 7·4 (2·4) | 6·5 (3·0) | .. | 0·22† (−0·52 to 0·95) | .. | 0·03 |

| Prevalence of depression at 12 months in all participants with data | 288 | .. | 124 (43%) | .. | 307 | .. | 149 (49%) | .. | .. | 0·76† (0·53 to 1·09) | 0·00 |

Data are mean (SD) or n (%) unless otherwise specified. OR less than 1 or negative mean difference favours intervention. OR=odds ratio. GDS-15=geriatric depression scale 15. ICC=model based intracluster correlation coefficient. Each model adjusted for place (Coventry and Warwickshire or northeast London), type of home, size of home, proportion of residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment at baseline, sex, on antidepressants at baseline, short physical performance battery at baseline, individual baseline GDS, and age at baseline (or mean of baseline GDS in the home and age at 12 months in prevalence analysis).

Two intervention and seven control residents excluded because of missing values in covariates.

One intervention and five control residents excluded because of missing values in covariates.

Seven intervention and 12 control residents excluded because of missing values in covariates.

We identified no evidence of a difference between intervention and control groups in any of our secondary comparisons, including for MMSE, fear of falling, and EQ-5D (tables 5, 6). Antidepressant use, mental health care team visits, and fracture and death rates did not differ between the intervention and control groups. No serious adverse events occurred during the exercise sessions or the assessments (appendix pp 3–5).

Table 5.

Secondary outcomes for all cohort participants (N=891)

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

Effect (95% CI) | ICC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

Control |

||||||||||||

| N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| 6 months | |||||||||||||||

| EQ-5D, self-completed | 214 | .. | 0·58 (0·38) | 201 | .. | 0·60 (0·36) | 214 | .. | 0·59 (0·36) | 201 | .. | 0·57 (0·37) | 0·03 (−0·02 to 0·08) | 0·00 | |

| EQ-5D, proxy-completed | 278 | .. | 0·44 (0·34) | 336 | .. | 0·47 (0·33) | 278 | .. | 0·45 (0·35) | 336 | .. | 0·44 (0·35) | 0·05 (−0·01 to 0·11) | 0·10 | |

| MMSE | 257 | .. | 19·5 (6·4) | 269 | .. | 19·1 (6·1) | 257 | .. | 18·8 (7·0) | 269 | .. | 17·8 (6·6) | 0·53 (−0·16 to 1·22) | 0·02 | |

| Fear of falling | 246 | 95 (39%) | .. | 281 | 132 (47%) | .. | 281 | 93 (38%) | .. | 281 | 136 (48%) | .. | 0·76 (0·51 to 1·15) | 0·00 | |

| Pain | |||||||||||||||

| None | 245 | 169 (69%) | .. | 278 | 184 (66%) | .. | 245 | 168 (69%) | .. | 278 | 196 (71%) | .. | 1·08 (0·70 to 1·66)* | 0·03* | |

| Moderate | 245 | 72 (29%) | .. | 278 | 82 (30%) | .. | 245 | 69 (28%) | .. | 278 | 72 (26%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Severe | 245 | 4 (2%) | .. | 278 | 12 (4%) | .. | 245 | 8 (3%) | .. | 278 | 10 (4%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Social engagement | |||||||||||||||

| Low | 276 | 27 (10%) | .. | 341 | 35 (10%) | .. | 276 | 43 (16%) | .. | 341 | 47 (14%) | .. | 1·11 (0·73 to 1·69)† | 0·06† | |

| Moderate | 276 | 77 (28%) | .. | 341 | 98 (29%) | .. | 276 | 72 (26%) | .. | 341 | 112 (33%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| High | 276 | 172 (62%) | .. | 341 | 208 (61%) | .. | 276 | 161 (58%) | .. | 341 | 182 (53%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| 12 months | |||||||||||||||

| EQ-5D, self-completed | 184 | .. | 0·56 (0·39) | 182 | .. | 0·60 (0·36) | 184 | .. | 0·56 (0·40) | 182 | .. | 0·58 (0·38) | 0·01 (−0·05 to 0·06) | 0·02 | |

| EQ-5D, proxy-completed | 232 | .. | 0·46 (0·35) | 294 | .. | 0·49 (0·33) | 232 | .. | 0·43 (0·36) | 294 | .. | 0·45 (0·35) | 0·01 (−0·06 to 0·08) | 0·17 | |

| MMSE | 227 | .. | 19·6 (6·4) | 234 | .. | 19·0 (6·3) | 227 | .. | 18·2 (7·5) | 234 | .. | 17·3 (6·9) | 0·02 (−0·78 to 0·83) | 0·03 | |

| SPPB | 231 | .. | 2·2 (2·4) | 261 | .. | 2·0 (2·1) | 231 | .. | 1·9 (2·4) | 261 | .. | 1·6 (1·9) | 0·30 (−0·05 to 0·64) | 0·09 | |

| Fear of falling | 211 | 84 (40%) | .. | 228 | 115 (50%) | .. | 211 | 76 (36%) | .. | 228 | 95 (42%) | .. | 1·07 (0·68 to 1·67) | 0·00 | |

| Pain | |||||||||||||||

| None | 216 | 143 (66%) | .. | 227 | 153 (67%) | .. | 216 | 155 (72%) | .. | 227 | 167 (74%) | .. | 1·07 (0·67 to 1·72)* | 0·00* | |

| Moderate | 216 | 68 (31%) | .. | 227 | 63 (28%) | .. | 216 | 51 (24%) | .. | 227 | 54 (24%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Severe | 216 | 5 (2%) | .. | 227 | 11 (5%) | .. | 216 | 10 (5%) | .. | 227 | 6 (3%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| Social engagement | |||||||||||||||

| Low | 235 | 22 (9%) | .. | 306 | 28 (9%) | .. | 235 | 27 (11%) | .. | 306 | 46 (15%) | .. | 1·08 (0·64 to 1·83)† | 0·14† | |

| Moderate | 235 | 58 (25%) | .. | 306 | 85 (28%) | .. | 235 | 80 (34%) | .. | 306 | 97 (32%) | .. | .. | .. | |

| High | 235 | 155 (66%) | .. | 306 | 193 (63%) | .. | 235 | 128 (54%) | .. | 306 | 163 (53%) | .. | .. | .. | |

ICC=model based intracluster correlation coefficient. EQ-5D=European quality of life-5 dimensions. MMSE=mini-mental state examination. SPPB=short physical performance battery.

For all pain.

For all social engagement.

Table 6.

Secondary outcomes for all cross-sectional participants (N=751)

|

Intervention |

Control |

Effect (95% CI) | ICC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | N | n (%) | Mean (SD) | |||

| EQ-5D, self-completed | 251 | .. | 0·55 (0·39) | 245 | .. | 0·57 (0·38) | 0·00 (−0·06 to 0·06) | 0·00 |

| EQ-5D, proxy-completed | 346 | .. | 0·45 (0·37) | 378 | .. | 0·44 (0·36) | 0·02 (−0·05 to 0·08) | 0·09 |

| MMSE | 284 | .. | 18·6 (7·3) | 285 | .. | 17·0 (6·9) | 0·68 (−0·46 to 1·82) | 0·00 |

| Fear of falling | 273 | 103 (38%) | .. | 280 | 110 (39%) | .. | 1·16 (0·79 to 1·71) | 0·00 |

| SPPB | 296 | .. | 1·9 (2·4) | 315 | .. | 1·9 (1·5) | 0·20 (−0·14 to 0·53)* | 0·00* |

| Pain | ||||||||

| None | 278 | 198 (71%) | .. | 281 | 213 (76%) | .. | 1·39 (0·92 to 2·08) | 0 |

| Moderate | 278 | 70 (25%) | .. | 281 | 61 (22%) | .. | .. | .. |

| Severe | 278 | 10 (4%) | .. | 281 | 7 (2%) | .. | .. | .. |

| Social engagement | ||||||||

| Low | 349 | 49 (14%) | .. | 386 | 51 (13%) | .. | 0·89 (0·57 to 1·38)† | 0·12† |

| Moderate | 349 | 108 (31%) | .. | 386 | 125 (32%) | .. | .. | .. |

| High | 349 | 192 (55%) | .. | 386 | 210 (54%) | .. | .. | .. |

ICC=model based intracluster correlation coefficient. EQ-5D=European quality of life-5 dimensions. MMSE=mini-mental state examination. SPPB=short physical performance battery.

For all pain.

For all social engagement.

Discussion

Provision of group exercise classes over 12 months to residents of care homes older than 65 years had no effect on depressive symptoms in this population, as measured by the GDS-15, irrespective of whether residents were depressed at baseline.

This is a large cluster randomised trial with robust findings. The results are clear and conclusively negative. Although uptake of the intervention was very good we recorded no evidence of any benefit on any of our primary or secondary outcome measures. The limits of the 95% CIs for the possible benefit from the intervention for cohort and depressed cohort analyses exclude the likelihood of a clinically important effect. Furthermore, in our cost–utility analysis the intervention was dominated by the control, showing that this is not a cost-effective intervention (appendix p 7).

Participating homes were broadly representative of UK care homes, and participant baseline characteristics were much the same as population values.8,22,23 That nearly half of our participants were depressed, and that only a quarter of these cases were identified as depressed in care-home records underscores the relevance of depression as an important and neglected health problem needing treatment (appendix p 2).8 A quarter of residents were excluded by care-home managers because their health was very poor, or because of concerns that approaching the resident might cause distress (figure 2). Residents excluded because of very poor health would have been unlikely to be able to participate in the exercise groups and thus unlikely to benefit from the intervention.

Prevalence of depressive symptoms between baseline and follow-up did not differ in either group suggesting that both control and active interventions were ineffective. Also, the pattern of use of antidepressant drugs, or mental health team visits, did not differ, which might have masked a beneficial effect from the intervention (appendix p 3).

These findings effectively exclude any possibility of a beneficial effect on depressive symptoms, as measured on the GDS-15, from this exercise intervention. We have not excluded the possibility that our intervention might improve mobility; the limits of the 95% CI for the improvement in the SPPB in both the cohort analysis (–0·05 to 0·64) and the cross sectional analysis (–0·10 to 0·58) include a minimum clinically important difference of 0·5.24,25

We are aware of one other cluster randomised trial (N=191, follow-up 6 months) and one individually randomised trial (N=134, follow-up 1 year) in care homes of exercise programmes that were much the same as ours with participants who had similar characteristics to ours.26,27 These studies also failed to show a benefit on depressive symptoms (panel). We are aware of two other trials in care homes that excluded people with substantial cognitive impairment. One (N=389) showed no benefit on depressive symptoms from Tai Chi while the other (N=82) did find a benefit on depressive symptoms from qigong.28,29

Panel. Research in context.

Systematic review

We have done three relevant systematic reviews to identify randomised controlled trials comparing the effect of an exercise intervention on depressive symptoms with usual care or an attention control in elderly residents of care homes. First, we updated our review of the effects of exercise on depression in elderly people.3 Search terms were: “exercise” OR “exercise therapy” OR “physical activity” OR “physical exercise” OR “dancing” OR “Tai Chi” OR Tai Ji OR “walking” OR “yoga” OR “physical fitness” OR “aerobic exercise” OR “exertion” AND “depression” OR “dysthymic disorder” OR “depressive disorder” OR “major depressive disorder” OR “depressive disorder major” OR “dysthymia” AND “elderly” OR “aged” OR “geriatric” OR “seniors” AND “randomised controlled trials”. Second, we updated our review of physical activity or the effects of physical activity on elderly people with dementia.5 Search terms were: “exercise” OR “exercise therapy” OR “physical activity” OR “physical exercise” OR “dancing” OR “Tai Chi” OR Tai Ji OR “Walking” OR “yoga” OR “physical fitness” OR “aerobic exercise” OR “exertion” AND “elderly” OR “Aged” OR “geriatric” OR “seniors” AND “dementia” OR “Alzheimer disease” AND “randomised controlled trials”. Finally we updated our unpublished systematic review of cluster randomised controlled trials in residential and nursing homes. Search terms were “randomised trial” OR “clinical trial” AND “long term care facility” OR “long term care” OR “assisted living” OR “group homes” OR “homes of aged” OR “residential facilities” OR “nursing home” OR “retirement homes” OR “retirement communities” AND “cluster randomisation” OR “cluster randomisation” OR “cluster” OR “clustered” OR “clustering” OR “clusters” OR “group-randomised” OR “group-randomised” OR “randomisation unit” OR “randomisation unit”. Our searches were done in Scopus and PubMed, for papers reported between Jan 1, 2010, to Feb 13, 2013. We indentified four relevant studies; Tsang and colleagues,28 Rolland and colleagues,27 Conradsson and colleagues,26 and Lam and colleagues.29

Interpretation

The populations included the trials by Tsang and colleagues28 and Lam and colleagues29 differ from our participants because they excluded residents with substantial cognitive impairment. Both the populations included, and the frequency and intensity of the exercise sessions, in the studies by Rolland and colleagues27 and Conradsson and colleagues26 are much the same as those in our trial. Neither, however, included a whole home component to the intervention.

Taken together with the earlier findings of Rolland and colleagues27 and Conradsson and colleagues,26 our findings show that regular moderately intense group exercise sessions do not live up to their promise as a treatment for depression in elderly residents of care homes. Nevertheless, exercise might be useful treatment for depression in fitter older people, including residents of care homes, who do not have substantial cognitive impairment and who are able to achieve more intense levels of sustained physical activity.

The whole home nature of the active intervention meant that masking data collection within the homes after randomisation was not possible. Also support from care-home staff with data collection might differ between intervention and control homes. In intervention homes we noted a consistent trend for the collection of more post-randomisation data. Our findings did not, however, change materially in a sensitivity analysis in which we imputed missing data or when an extreme scenario sensitivity analysis was done (data not shown).

The prevalence of depression in all residents at the end of the study is an important analysis to ensure the findings apply to all residents rather than only relatively healthy survivors. In this analysis we recruited more participants in the intervention homes than in the control homes after randomisation. Results were, however, unchanged by excluding the post randomisation participants. Since this is one of the largest trials done in a care-home setting and intra-cluster correlation coefficients are mostly close to zero, we achieved precise estimates for our effect sizes, suggesting that our conclusions are robust.

We designed an intervention package that had a good theoretical grounding designed to be delivered, over the long term, in a care-home environment. Participants had good exposure to the exercise sessions without any serious adverse events. The session design included ambulatory exercises, but because of the poor physical health and abilities of participants in the exercise group, the exercises were largely done while seated, reducing the intensity of the exercises. In a parallel process assessment we noted that our intervention had little effect on physical activity within homes outside the times of exercise sessions8 and that although overall session attendance was good, many participants, particularly those with depression, attended too few sessions to gain the anticipated benefits. Our approach, although popular with the homes, does not seem to have delivered an adequate dose to those with greatest need. Exercise interventions targeted at the fittest, least cognitively impaired care-home residents with depression could be effective.28–32

We have achieved very precise estimates of the possible effect of the intervention. The study is, however, limited by the sensitivity of the measures used. Other, more sensitive, outcome measures might have shown a benefit, particularly for health-related quality of life. Nevertheless, this large study shows that group exercise is unlikely to be an effective approach for prevention and treatment of depression among elderly residents of care homes. We cannot exclude the possibility that this intervention had beneficial effects on other unmeasured outcomes such as cardiovascular fitness or staff morale within care homes.

Despite robust methodology, a strong theoretical grounding and good uptake of a moderately intensive exercise intervention, we identified no evidence that our intervention had a positive effect on any of our carefully selected primary or secondary outcomes. This evidence does not support the use of this type of intervention to reduce the burden of depressive symptoms in residents of care homes, and alternative strategies for this common and important problem are needed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme (project 06/02/01). The sponsors of the study played no part in the preparation of this Article. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Health Technology Assessment programme, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health. This project benefited from facilities funded through Birmingham Science City Translational Medicine Clinical Research and Infrastructure Trials Platform, with support from Advantage West Midlands. We thank the care-home owners, providers, managers, staff, residents and their families who participated in this trial.

Contributors

MU was chief investigator; SE, SL, BS, A-MS, AS, ST, MT, and MU were coapplicants for funding and designed the original study protocol; NA, SL, BS, ST, and MT developed the intervention; RP and A-MS were involved in recruitment processes; A-MS was responsible for research ethics; DE, RP, and KS collected and managed the data; SB, SE, AD, BS, KDO, KS, AS, and MU developed the statistical analysis plans; SB, DE, AD, KS, KD-O, and SE analysed the data; all authors contributed to interpretation of results, and drafting of the final Article, including critique for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Llewellyn-Jones R, Baikie K, Smithers H. Multifaceted shared care intervention for late life depression in residential care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;319:676–682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutcliffe C, Burns A, Challis D. Depressed mood, cognitive impairment, and survival in older people admitted to care homes in England. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:708–715. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180381537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, Atherton NM, Lamb SE. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:180–185. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craft LL, Perna FM. The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6:104–111. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter R, Ellard D, Rees K, Thorogood M. A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on physical functioning, quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1000–1011. doi: 10.1002/gps.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellard D, Taylor S, Parsons S, Thorogood M. The OPERA trial: a protocol for the process evaluation of a randomised trial of an exercise intervention for older people in residential and nursing accommodation. Trials. 2011;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Underwood M, Eldridge S, Lamb S. The OPERA trial: protocol for a randomised trial of an exercise intervention for older people in residential and nursing accommodation. Trials. 2011;12:27. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Underwood M, Lamb SE, Eldridge S. Exercise for depression in care home residents: a randomised controlled trial with cost-effectiveness analysis (OPERA) Health Technol Assess. 2013 doi: 10.3310/hta17180. published online May 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodard CM, Berry MJ. Enhancing adherence to prescribed exercise: structured behavioral interventions in clinical exercise programs. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2001;21:201–209. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowensteyn I, Coupal L, Zowall H, Grover SA. The cost-effectiveness of exercise training for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20:147–155. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karageorghis CI, Priest D-L. Music in the exercise domain: a review and synthesis (Part II) Int Rev Sport Exercise Psychol. 2011;5:67–84. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2011.631027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jongenelis K, Pot AM, Eisses AM. Diagnostic accuracy of the original 30-item and shortened versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale in nursing home patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:1067–1074. doi: 10.1002/gps.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The EuroQol Group EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. MD State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JN, Hawes C, Fries BE. Designing the national resident assessment instrument for nursing homes. Gerontologist. 1990;30:293–307. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinkers DJ, Gussekloo J, Stek ML. The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) detects changes in depressive symptoms after a major negative life event. The Leiden 85-plus Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:80–84. doi: 10.1002/gps.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpenter J, Kenward M. Missing data in randomised controlled trials—a practical guide. National Institute for Health Research; Birmingham: 2008. p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter J, Goldstein H, Kenward M. REALCOM-IMPUTE software for multilevel multiple imputation with mixed response. J Statistic Software. 2011;45:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutcliffe C, Cordingley L, Burns A. A new version of the geriatric depression scale for nursing and residential home populations: the geriatric depression scale (residential) (GDS-12R) Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:173–181. doi: 10.1017/s104161020000630x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koehler M, Rabinowitz T, Hirdes J. Measuring depression in nursing home residents with the MDS and GDS: an observational psychometric study. BMC Geriatr. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon S, Perera S, Pahor M. What is a meaningful change in physical performance? Findings from a clinical trial in older adults (the LIFE-P study) J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:538–544. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conradsson M, Littbrand H, Lindelof N, Gustafson Y, Rosendahl E. Effects of a high-intensity functional exercise programme on depressive symptoms and psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:565–576. doi: 10.1080/13607860903483078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A. Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease: a 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsang HW, Fung KM, Chan AS, Lee G, Chan F. Effect of a qigong exercise programme on elderly with depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:890–897. doi: 10.1002/gps.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam LC, Chau RC, Wong BM. A 1-year randomized controlled trial comparing mind body exercise (Tai Chi) with stretching and toning exercise on cognitive function in older Chinese adults at risk of cognitive decline. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:568.e15–568.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billinger SA, Vidoni ED, Honea RA, Burns JM. Cardiorespiratory response to exercise testing in individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:2000–2005. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.07.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill TM, DiPietro L, Krumholz HM. Role of exercise stress testing and safety monitoring for older persons starting an exercise program. JAMA. 2000;284:342–349. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theou O, Stathokostas L, Roland KP. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:569194. doi: 10.4061/2011/569194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.