Introduction

Post transplant parasitic infections are a rarity and occur in around 2% of transplant recipients1; the intestinal helminth Strongyloides stercoralis (Ss) is found in contaminated soil in hot and humid tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, South and East Asia, and South America. Infective larvae from contaminated soil enter the host venous system from the skin to end up in the lungs and are then ingested into the GI tract by the pharynx where they mature into adults.2 Approximately half of the immune competent hosts become carriers and the remainder usually present with mild abdominal and respiratory symptoms.3 Transplant recipients receive steroids, have altered cellular immunity, and are at increased risk for hyperinfection syndrome because of an accelerated auto-infective cycle, rapid multiplication, and systemic larval dissemination.4 This can result in serious complications including GI bleeding, bacteremia, meningitis, liver abscesses, pneumonia, and death.5 We report a Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in a Saudi kidney recipient with recurrent Streptococcus bovis bacterial meningitis and significant weight loss 2 months after deceased donor kidney transplantation.

Case report

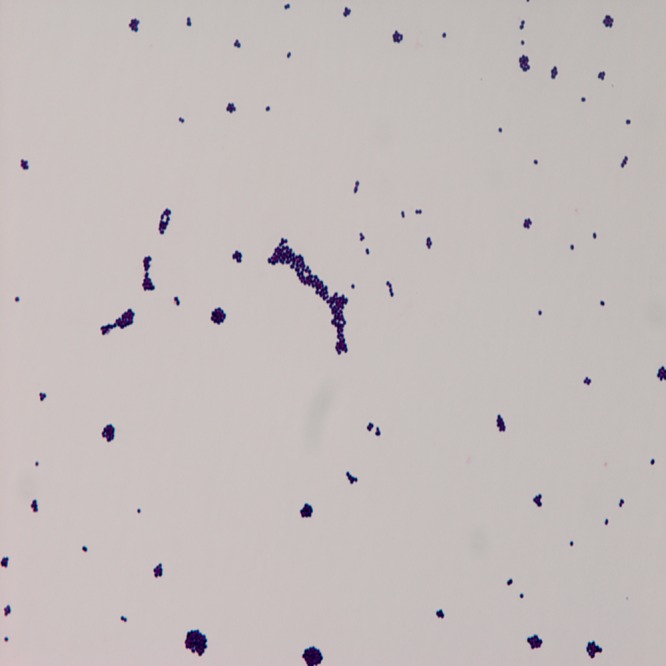

A 27-year-old Saudi male with end stage renal disease secondary to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis on regular hemodialysis for 4 years, received a 4 HLA antigen mismatch standard criteria deceased donor kidney from an expatriate Indian donor. Induction comprised anti-thymocyte globulin and methylprednisolone with immediate graft function after 8 hours of cold ischemia. He was discharged home on tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisolone with a serum creatinine of 102 μmol/L. Two months later, he was admitted complaining of occipital headache, neck pain, vomiting, photophobia, and blurred vision but no seizures. He also gave a history of vague abdominal pain and diarrhea. On examination, he was afebrile with normal vital signs, a chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain were unremarkable, and a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample was compatible with acute bacterial meningitis (ABM) and culture positive for Streptococcus bovis but no vegetations were documented on echocardiography (Figure 1). The total and differential white cell count was within normal limits and all blood cultures were negative. With a diagnosis of ABM, the mycophenolate was discontinued and tacrolimus was reduced. He received a 2-week course of appropriate broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics with improvement in symptoms. This recipient had also received 10 mg dexamethasone 6 hourly until S. bovis was discovered in the CSF. In view of the association of S. bovis with colonic cancer, he underwent a colonoscopy that was unremarkable and he was discharged home on his original triple immunosuppression.

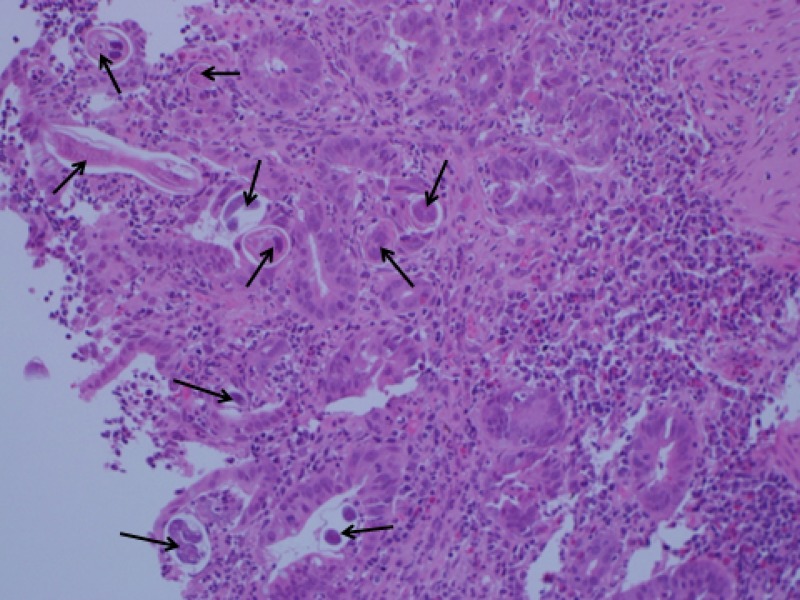

Figure 1.

Gram stain film of the cerebrospinal fluid culture growing Streptococcus bovis.

He was readmitted after 3 weeks with fever, headache, persistent vomiting, and neck pain, and a 20 kg weight loss. He was febrile (38.5°C) with tachycardia and pallor with mild signs of meningeal irritation. He also gave a history of abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea for the preceding month associated with weight loss. A CT brain scan was again unremarkable and an MRI revealed pachymeningeal enhancement but no abscess. A plain abdominal film was reported as a paralytic ileus/sub-acute intestinal obstruction, CSF showed a high neutrophil count, however like the blood sample, was culture negative (Table 1). The impression was a recurrence of ABM for which he again received intravenous antibiotics with a reduction in the immunosuppression. The next day, he developed a cough with sputum, a chest examination and chest x-ray were unremarkable, but Escherichia coli, sensitive to cephalosporins was isolated from the sputum. In view of the weight loss and diarrhea, thyroid function tests were also requested, which revealed a slightly elevated T4 and a low thyrotropin (TSH). Thyroiditis was also suggested by the low uptake on the nuclear scan with a negative autoimmune screen, and he was started on carbimazole. The pp65 antigen and Brucella were negative and all tumor markers were also within normal. Mild eosinophilia in the differential count along with abdominal symptoms was suggestive of a parasitic infestation but all stool analyses were negative for ova and parasites (O+P). The continuing abdominal symptoms and weight loss prompted an upper GI endoscopy, which revealed multiple erosions in D1 and D2 and tissue samples confirmed intramucosal nematodes compatible with Ss (Figure 2). The infectious diseases staff recommended treatment with a 10-day twice daily course of 400 mg albendazole with improvement in abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. The stool analyses had repeatedly been negative for Ss and no O+P were ever documented and the preoperative (before immunosuppression) eosinophil count was also found to be normal. The regular immunosuppression was resumed after completing the intravenous antibiotics. He regained 8 kg in the next 3 weeks and was back to his normal weight in 3 months. At 36 months, he remains symptom free with excellent renal function.

Table 1.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis during the two admissions*

| Test | First admission | Second admission |

|---|---|---|

| CSF glucose | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| Blood glucose | 6.3 | 6.5 |

| Protein | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| White cells | 34/cu mm | 320/cu mm |

| Polymorphs | 96% | 97% |

| Lymphocytes | 4% | 3% |

| Cryptococcus antigen | Negative | Negative |

Leukocytes, overwhelmingly neutrophils, are present in both samples.

Figure 2.

Widespread presence of Strongyloides stercoralis worms (black arrows) in a duodenal tissue specimen. Low magnification H&E stain.

Discussion

The intestinal parasite S. stercoralis is not endemic in Saudi Arabia; however, the majority of deceased donors are expatriates from endemic areas of South India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Donor-linked parasitic transmission has been suspected in transplant recipients who received organs from donors from endemic areas or proven when different recipients developed Ss after receiving different organs from the same donor.6–8 In our case, it is unlikely that this infection was donor derived because the recipient of the sister kidney did not develop any symptoms, and neither a donor eosinophil count nor a donor serum sample was available to confirm Ss IgG antibodies with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).5 Cyclosporine A has been reported to confer immunity against Ss9 but both kidney recipients in this case were receiving tacrolimus.

Expatriate workers in Saudi Arabia who become deceased donors from known Ss-endemic areas should be considered a transmission risk and predonation screening for this parasite and other imported infections would be beneficial. For Ss, screening with eosinophil count and IgG antibodies is desirable, but the unreliable history and short period of evaluation remains an obstacle for productive screening. This deceased donor was from an endemic area but the required screening was not performed and the use of steroids in donor preconditioning enhances the potential for Ss dissemination and hyperinfection.7 In addition, this donor received regular dexamethasone following the head injury, and the recipient was given bolus steroids as part of induction and both would have played a part in reactivating Ss, causing hyperinfection and dissemination in the recipient.10 The source of this transmission remains a mystery, there being no direct evidence that this Ss infection was donor derived, first because our Saudi recipient had never traveled to an endemic area and second, the other Saudi who received the sister kidney also did not develop any symptoms.

The majority of Ss cases present within 1–3 months after transplantation, and our recipient developed symptoms 2 months post transplant. Meningeal symptoms, the positive CSF culture and the E. coli from the sputum represent the bacteremia associated with unrestricted larval migration through the bowel wall6,11 that can result in a high incidence of S. bovis meningitis, especially after steroid therapy.12 The ability to cause autoinfection makes this parasite particularly virulent, which in immunocompromised recipients can result in the hyperinfection syndrome with larval proliferation in various organs including the lungs, kidneys, thyroid and the brain, with serious consequences.9,13,14 Because mortality in transplant recipients who develop the hyperinfection syndrome is very high reaching up to 85%,5,9,15 it has been suggested that diagnosis in the donor should preclude transplantation.7 Multisystem involvement is not rare, as in our case, with paralytic ileus, E. coli acute tracheobronchitis, meningitis, and weight loss.12–14,16 Saudi Arabia is not considered endemic for Ss17 and may be the reason it was not considered in the differential diagnosis. Early diagnosis is vital but is liable to get delayed in non-endemic areas because the disease is neither suspected, nor pursued if the stool samples are negative, as in our case. Peripheral eosinophil counts may be low because of steroids and thus unhelpful in affected transplant recipients and diarrhea is generally considered to be drug related2,6; our patient received high dose dexamethasone that might have masked the oesinophilia in the first admission. In case the diarrhea continues, it is important to test several fresh stool samples and an agar culture for better yields of the parasite.13 Antibodies to Ss using ELISA can confirm diagnosis, especially when repeated stool testing is negative.5

Weight loss is common in GI Ss infection because of malabsorption,7,13 which in our recipient was ascribed to mild thyrotoxicosis, diarrhea, cytomegalovirus, and other prevailing infective phenomena. Because ivermectin, considered the drug of choice was not available,7,15,18 the recipient was given albendazole 400 mg for 10 days. As reactivation and relapse remains a possibility in immunosuppressed patients, some researchers have advised intermittent monthly therapy.19

Strongyloides hyperinfection was neither suspected nor confirmed in the first admission and the symptoms that led to urgent admission were primarily related to the central nervous system (CNS) along with mild abdominal symptoms with weight loss. The meningeal symptoms were overwhelming and overshadowed the abdominal symptoms, and the negative stool samples were further misleading. The focus remained on the CNS, especially when S. bovis was isolated from the CSF confirming acute bacterial meningitis. It is thought that migration of larvae through the bowel wall resulted in the bacteremia6 that caused the first meningeal symptoms and then recurred because hyperinfection continued. In retrospect, our recipient had abdominal symptoms and would have benefitted from an upper GI endoscopy, because Ss were not diagnosed until its eventual discovery on duodenoscopy. The abdominal symptoms were present at the time of the first admission and had the patient been more cooperative, we could perhaps have diagnosed Ss earlier, with duodenoscopy. During the second admission, the patient also developed a cough with E. coli-positive sputum indicating, in retrospect perhaps, another wave of Ss driven bacterial translocation. This is the main reason for the reported Klebsiella pneumonia and S. bovis acute bacterial meningitis, in patients with Ss, especially those receiving steroids.11,12

This however is the first report from Saudi Arabia of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome with recurring ABM in a Saudi kidney recipient. Despite a relatively late diagnosis and the unavailability of ivermectin, this recipient had a good outcome.

In conclusion, Ss is a serious disease and requires a high index of suspicion in non-endemic areas and all donors from endemic areas should be screened. Abdominal symptoms, eosinophilia, pruritis, or asthma in any transplant recipient should warrant examination of fresh stool samples along with ELISA testing for IgM and IgG antibodies. Treatment should be initiated when Ss is suspected because delay in treatment can be fatal5,9,16 and should include ivermectin.6,7,18 Repeated stool examination and therapy are also recommended because relapses are common.19

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Taqi T. Khan, Riyadh Military Hospital, Renal Transplant Surgery, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: taqikahn@yahoo.com. Fatehi Elzein, Riyadh Military Hospital, Infectious Diseases, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: fatehielzein@yahoo.com. Abdullah Fiaar, Riyadh Military Hospital, Pathology, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: Faheem Akhtar. Faheem Akhtar, Riyadh Military Hospital, Transplant Nephrology, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: drfaheemakhtar@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Valar C, Keitel E, Dal Pra RL. Parasitic infection in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:460. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Laiye AP. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1411. doi: 10.1086/630201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol. 17:208. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.208-217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Davila P, Fortun J, Lopez-Valez R, Norman F, Montes de Oca M, Zamarrón P, González MI, Moreno A, Pumarola T, Garrido G, Candela A, Moreno S. Transmission of tropical and geographically restricted infections during solid organ transplantation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:60–96. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00021-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim S, Katz K, Krajden S, Fuksa M, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians. Risk factors, diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2004;171:479–484. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-hernandez MJ, Ruiz-Perez-Pipaon M, Canas E, Bernal C, Gavilan F. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection transmitted by liver allograft in a transplant recipient. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2637–2640. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton KW, Abt PL, Rosenbach MA, Bleicher MB, Levine MS, Mehta J, Montgomery SP, Hasz RD, Bono BR, Tetzlaff MT, Mildiner-Early S, Introcaso CE, Blumberg EA. Donor-derived Strongyloides stercoralis infections in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;91:1019–1024. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182115b7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Youssef B, Baron P. Strongyloides stercoralis infection from pancreas allograft. Transplantation. 2005;80:997. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000173825.12681.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsoum RS. Parasitic infections in transplant recipients. Nature. 2006;2:490–502. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas MC, Costello SA. Disseminated Strongyloidiasis arising from a single dose of dexamethasone before stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52:520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaeffer MW, Buell JF, Gupta M, Conway GD, Akhter SA, Wagoner LE. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki Y, Taniguchi T, Kinjo M, McGill RL, McGill AT, Tsuha S, Shiiki S. Meningitis associated with Strongyloides in an area endemic for Strongyloides and human T-lymphotropic virus-1: a single center experience in Japan between 1990 and 2010. Infection. 2013;41:1189–1193. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0483-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltran Catalan S, Albiach JFC, Garcia AIM, Martinez EG, Teruel JLC, Mateu LMP. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in kidney transplant patients. Nefrologia. 2009;29:482–485. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.2009.29.5.4525.en.full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller S. Helminthic infections in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1988;8:133–135. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060080109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balagopal A, Mills L, Shah A, Subramanian A. Detection and treatment of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome following lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarr PE, Miele PS, Peregoy KS, Smith MA, Neva FA, Lucey DR. Case report: Rectal administration of ivermectin to a patient with Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:453–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekait MA, Ansary LA, Zamel F. Prevalence of pathogenic intestinal parasites among Saudi rural schoolchildren. Eur J Pub Health. 1993;4:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiodini PL, Reid AJ, Wiselka MJ, Firmin R, Foweraker J. Parenteral ivermectin in Strongyloides hyperinfection. Lancet. 2000;335:43. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler CG, Lindsay I, Levin J, Sweny P, Fernando ON, Moorhead JF. Recurrent hyperinfestation with Strongyloides stercoralis in a renal allograft recipient. BMJ. 1982;285:1394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6352.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]