Abstract

A Mexican airline pilot had clinical manifestations of illness after a five-day stay in Lima, Peru. Six months later in Mexico, he was given a diagnosis of infection with Cyclospora cayetanensis by using coproparasitoscopic serial tests. He was treated twice with nitazoxadine successfully.

Case Report

A 26-year-old man from Mexico City had clinical manifestations of illness after a five-day stay in Lima, Peru. The patient was an airline pilot and reported episodes of diarrhea without mucus, pus, or blood. He had a history of periumbilical colic-like abdominal pain, push, tenesmus, meteorism, audible borborygmi, semi-liquid to pasty feces, and 5–8 explosive bowel movements a day. He also reported malaise, asthenia, adynamia, moderate headache, dizziness, nausea, but no emesis; these conditions lasted approximately 14 days.

The symptoms became worse and the patient had persisting dizziness, blurred vision, orthostatic hypotension, and sensation of postprandial fullness with colic pain, tenesmus, and right sacroiliac burning pain. He had frequent bowel movements (2–3 per day) with traces of blood in feces.

After 10 days of disease progression, the patient had deep pain in the right upper quadrant, a hypersensitive vesicular region, fever, diaphoresis, malaise, paresthesias, and belt-like pain in the right hypochondrium from D11 to L3. Bowel movements increased again to 6–8 per day, and the patient had severe diffuse abdominal pain, chills, and myalgia.

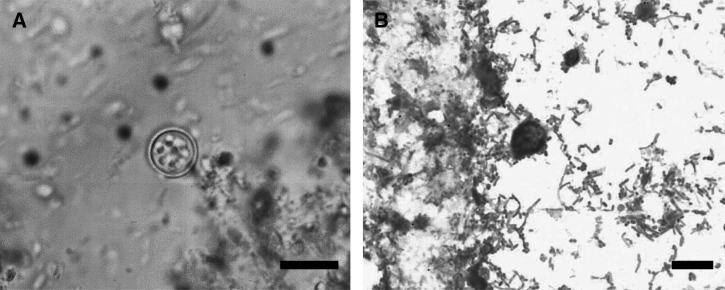

Because of persistence for six months of clinical manifestations and negative results for multiple laboratory and imaging tests, including that for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and a poor response to therapy given by different private physicians, the patient came to the medical unit at the Mexican Institute of Social Security. Cyclospora infection was diagnosed by examining stool specimens at the medical unit in collaboration with the Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico. Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts were detected by using sedimentation and flotation (Faust) tests (Figure 1A) , coproparasitoscopic serial (CPS) tests, and Ziehl-Neelsen stain (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Oocyst of Cyclospora cayetanensis in an unstained wet mount of stool (A) and in a modified Ziehl–Neelsen-stained fecal smear (B) (Bar = 10 μm).

The patient was treated since the onset of the symptoms with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), four times over a two-week period and then four times over a four-week period. However, because of persistence of symptoms and recurrence when this treatment stopped, he was then treated with nitazoxadine, 7.5 mg/kg, twice a day for seven days.

The patient completed the prescribed treatment and reported reduction in the number of bowel movements and improvement of prognosis at the second day of treatment. Ten days after the end of the first treatment, nitazoxanide was prescribed as a second therapy. Although the CPS staining results were negative, the patient reported discrete abdominal pain with push and tenesmus, which stopped at the third day of treatment.

Control CPS tests and staining were performed 10, 20, and 30 days after initial treatment; all tests showed negative results. The patient was then released and he was given information about prophylactic measures to prevent cyclosporiasis and other parasitic diseases.

Discussion

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an emerging protozoan pathogen that causes an acute or chronic diarrheal disease known as cyclosporiasis, which can affect immunocompetent and immunocompromised (infected with human immunodeficiency virus) humans. Cyclosporiasis was firstly described and related to a coccidian in feces of patients with diarrhea in 1979 by Ashford.1

After the studies of Ortega and others,2–4 the taxonomic classification of C. cayetanensis was determined. These investigators induced sporulation of so-called cyanobacterium-like bodies by using potassium dichromate solution. It was observed that these microorganisms contained two sporocyts per oocyst; inside of each sporocyst were two sporozoites2. Consequently, the new species was systematically classified within the phylum Apicomplexa, placing the parasite in the coccidian genus Cyclospora. The species designation C. cayetanensis was proposed because the research studies were first performed at University of Lima, Peru (Cayetano Heredia University).3

This cosmopolitan apicomplexan parasite is endemic to countries such as Nepal, Haiti, Guatemala, and Peru. However, it can also be found as an enteropathogen that causes traveler's diarrhea.4 This condition has been associated with intake of fruits, such as strawberries or raspberries, and with different types of green vegetables such as lettuce contaminated with C. cayetanensis sporulated oocysts.4 C. cayetanensis is an obligate intracellular protozoan that has an enteroepithelial and direct life cycle, combined with asexual (merogony or schizogony) and sexual reproduction (gametogony), respectively.5

The asexual cycle is initiated by ingesting sporulated oocysts from contaminated water, fresh vegetables, or food. In the duodenum, oocyst excystation occurs and results in formation of four invasive sporozoites that adhere and penetrate the enterocyte membrane of the small intestine. These sporozoites undergo an initial (first) merogony inside a parasitophorous vacuole located in the luminal pole of infected host cells6,7 and give rise to type I meronts containing 8–12 merozoites. Merozoites then rupture infected host cells and are released. At this stage, they can infect other enterocytes, initiating the second merogony.5–7

Type II meronts develop into four merozoites. After they are released from enterocytes, these merozoites begin so-called sexual reproduction. Each daughter merozoite differentiates into a male microgamont or female macrogamont. Male microgamonts produce many microgametes, each of which is capable of fertilizing a mature macrogamont. After syngamy, newly formed oocysts will be formed and shed with the feces.5,6

Newly released oocysts are unsporulated. At this stage, they are unable to cause human infections because an internal sporoblast, instead of sporocysts with sporozoites, is found in freshly passed oocysts and because sporulation occurs only under specific environmental conditions (high temperature and humidity). In general, the mode of transmission is through ingestion of sporulated oocysts present in contaminated food or water.7

The prepatent period of C. cayetanesis is variable and short (average = 7 days). Sometimes, especially in disease-endemic areas, cyclosporiasis does not have any symptoms (in healthy carriers).8 When clinical manifestations are present, prodromes begin with 1 or 2 days of malaise and fever. Subsequent symptoms include abrupt watery diarrheal episodes, with 4–10 bowel movements per day that are abundant and contain mucus. Initially, there is no blood in the feces. Blood appears in lower quantities subsequently after onset of initial symptoms. Similarly, asthenia, as well as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and flatulence, are reported frequently.5

Episodes of signs and symptoms are inconsistent (range = 3 to more than 100 days). Abrupt reduction of symptoms is generally associated with disappearance of oocysts from feces.

Diagnosis of cyclosporiasis by laboratory studies is direct when microscopy is used. Unsporulated oocysts in concentration and flotation CPS tests are observed as hyaline spherules 8–10 μm in diameter, which have a morula or mulberry-like structure composed of 6–9 refractile globules. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining identifies oocysts as intense red spherical structures 8–10 μm in diameter.5,8–10

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (160 mg/800 mg), twice a day for seven days, has been presecribed in many studies. If symptoms persist, another treatment for seven days with this drug combination is highly recommended. If oocysts are still found in feces, especially in immunosuppressed patients, who have the most severe symptoms, a 3–7 day treatment should be administered for 3–4 months.11

This case report draws attention to all health professionals to consider C. cayetanensis as potential etiologic cause of persistent human enteritis. Although it was described more than a decade ago, cyclosporiasis is still rarely reported in private or public health laboratories. Unawareness of this disease might often lead to misdiagnosis and incorrect treatments. The possible explanation for this problem is lack of information among clinicians and laboratory workers about this protozoan parasite and its impact on public health.

In addition, in many cases clinical manifestations are self-limited and diagnosis can be delayed when patients seek medical attention while they are in a relapse state or have a chronic disease. The medical practice of erroneously administered antibiotics for any diarrheal symptoms should also be considered. Moreover, the unhealthy habit of self-medication or seeking of empiric therapy will exacerbate this condition.

Furthermore, we emphasize that TMP/SMX was not an effective treatment compared with nitazoxanide. Therefore, we suggest nitazoxanide as an alternative treatment for patients with low or null response to TMP/SMX therapy, or if the patient is allergic to TMP/SMX.12

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Enrique Graue Wiechers (UNAM, MEXICO), Dr. Rosalinda Guevara (UNAM, MEXICO) and Dr. Klaus T. Preissner (JLU-Giessen, Germany) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by the LOEWE-Initiative der Landesförderung (III L 4 – 518/15.004 2009 to Guillermo Barreto) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, BA 4036/1-1 to Guillermo Barreto) H. A. Cabrera-Fuentes is member of the International Research Training Group 1566 (PROMISE) and is supported by the DFG. This work was supported in part by the Dean?s Office of the Faculty of Chemical Sciences and the Director of Strategic Planning and Evaluation at the Universidad Autonoma Benito Juarez de Oaxaca. This work was done according to the Program of competitive growth of Kazan Federal University supported by the Russian Government.

Disclosure: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest.

Authors' addresses: José T. Sánchez-Vega, Parasitology Laboratory, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, E-mail: pptrini@hotmail.com. Héctor A. Cabrera-Fuentes, Institute of Fundamental Medicine and Biology, Kazan Federal University, Tatarstan, Russia, and Biochemistry Institute, Medical School, Justus-Liebig University, Giessen, Germany, E-mail: hector.a.cabrera-fuentes@biochemie.med.uni-giessen.de. Addi J. Romero-Olmedo, Faculty of Chemical Sciences, Universidad Autonoma Benito Juarez de Oaxaca, Oaxaca, Mexico, and Lung Cancer Epigenetic, Max-Planck-Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, Germany, E-mail: addi.romero@mpi-bn.mpg.de. José L. Ortiz-Frías, Unidad Medica Familiar, Delegacion Sur, Unidad 21 Valle de Mexico, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico City, Mexico, E-mail: joseortizfrias@yahoo.com.mx. Sokolina Flura, Institute of Fundamental Medicine and Biology, Kazan Federal University, Tatarstan, Russia, E-mail: flura.sokolina@kpfu.ru. Guillermo Barreto, LOEWE Research Group Lung Cancer Epigenetic, Max-Planck-Institute for Heart, and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, Germany, E-mail: guillermo.barreto@mpi-bn.mpg.de.

References

- 1.Ashford RW. Occurrence of an undescribed coccidian in man in Papua New Guinea. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1979;73:497–500. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1979.11687291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortega YR, Sterling CR, Gilman RH, Cama VA, Diaz F. Cyclospora species: a new protozoan pathogen of humans. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1308–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortega YR, Gilman RH, Sterling CR. A new coccidian parasite (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from humans. J Parasitol. 1994;80:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortega YR, Sanchez R. Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food-borne and waterborne parasite. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:218–234. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00026-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansfield LS, Gajadhar AA. Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food- and waterborne coccidian parasite. Vet Parasitol. 2004;126:73–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega YR, Nagle R, Gilman RH, Wateanabe J, Miyagui J, Quispe H, Kanagusuku P, Roxas C, Sterling CR. Pathologic and clinical findings in patients with cyclosporiasis and a description of intracellular parasite life-cycle stages. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1584–1589. doi: 10.1086/514158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortega YR, Sterling CR, Gilman RH. Cyclospora cayetanensis. Adv Parasitol. 1998;40:399–418. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nessi PA, de Gumaz RC, Wagner AC, Dorta PA, Galindo PM, Vethencourt M, de Perez GV. Reporte de cinco casos de cyclosporiosis en un centro penitenciario en Venezuela. Rev Inst Nac Hig. 2011;42:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chacín-Bonilla L, Barrios F. Cyclospora cayetanensis: biología, distribución ambiental y transferencia. Biomedica. 2011;31:132–144. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572011000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vásquez TO, Jiménez DR, Campos RT, Valencia RS, Romero CR, Gamez AV, Martínez-Barbosa I. Infección por Cyclospora cayetanensis. Diagnóstico de laboratorio. Rev Latinoam Microbiol. 2000;42:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verdier RI, Fitzgerald DW, Johnson WD, Pape JW. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole compared with ciprofloxacin for treatment and prophylaxis of Isospora belli and Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:885–888. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmer SM, Schuetz AN, Franco-Paredes C. Efficacy of nitazoxanide for cyclosporiasis in patients with sulfa allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:466–467. doi: 10.1086/510744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]