Abstract

Background

Thiopurines are considered immunosuppressive agents and may be associated with an increased risk for infections. However, few inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are appropriately vaccinated, and data on their ability to mount an immune response are vague. We evaluated the effects of the thiopurines, azathioprine (AZA) and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), on cellular and humoral immune responses in IBD patients.

Methods

A prospective clinical investigation was conducted on IBD patients referred for thiopurine treatment. Immune competence was evaluated by assessing lymphocyte counts and phenotype, response to mitogen and antigen stimulation, immunoglobulin levels, and response to pneumococcal and tetanus vaccines (before treatment, week 0), and to Haemophilus influenza type b vaccine (at week 24).

Results

Thirty-one Crohn’s disease and 12 ulcerative colitis patients who completed at least 24 weeks of therapy were included. The posttherapy average 6-MP dose was 1.05 ± 0.30 mg/kg, and white blood cell counts had decreased significantly from baseline values (P < 0.002). The posttreatment response to mitogens and antigens and the immunoglobulin levels were unchanged. Responses to vaccines were normal both in thiopurine-naïve and thiopurine-treated patients, suggesting that these patients were immunologically intact while on thiopurine therapy and capable of generating normal immune responses in vivo.

Conclusions

There is no evidence for any intrinsic systemic immunodeficiency in IBD patients. Thiopurines at the doses used for treating IBD showed no significant suppressive effect on the systemic cellular and humoral immune responses evaluated. Thiopurine-treated IBD patients can be safely and efficiently vaccinated.

Keywords: immunomodulators, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, immune response

The thiopurine immunomodulatory agents, azathioprine (AZA) and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), are increasingly used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs). Their efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission in active Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) has been demonstrated in many studies and metaanalyses. 1,2 The exact mechanism of action remains unclear even after 40 years of use. The prevailing theory is that the active metabolites of these agents interfere with nucleic acid synthesis and have antiproliferative effects on activated lymphocytes.3 Tiede et al4 recently challenged this concept, claiming that thiopurines may induce lymphocyte apoptosis. Their findings shed new light on the mechanism of action of an old drug by suggesting that the 6-MP metabolite, 6-thio-GTP, causes apoptosis of CD4+ T lymphocytes, in the process of being activated, by inhibiting Rac1.

Whether by inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation or by inducing apoptosis, thiopurine treatment is associated with leukopenia. Depending on the metabolic pathway, leukopenia may be life-threatening, as it may increase the risk of overwhelming infections. Infections have, however, been reported without relation to the degree of leukopenia.5,6 An increased susceptibility to infections while on thiopurine therapy has been reported in several studies,7,8 although this may be more relevant for specific infections (e.g., herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV], cytomegalovirus [CMV]).9,10 If patients on thiopurines were more susceptible to infections, it would be prudent to initiate preventive strategies by vaccinating them before the onset of therapy. Only recently have guidelines been developed for vaccination in patients with IBD.11,12 These publications recommend the use of vaccines prior to initiating immunomodulator therapy, but Melmed et al’s13 physician questionnaire and serological response-based study revealed that routine vaccination with tetanus toxoid, pneumococcus, and hepatitis B vaccine was avoided in the majority of IBD patients who were on thiopurines. These authors reported that an adequate serologic response was found in only 33% of patients (n = 9) in a subgroup assessed for hepatitis B virus serology. Two reasons have been proposed for not vaccinating IBD patients who are on thiopurine therapy. The first stems from the concept that cellular and humoral immune responses in these patients would be defective, thus eliminating the likelihood of effective immune responses to vaccines. The second reason is that immune-mediated inflammatory diseases may flare up on the immune activation associated with vaccination. Thus, not only would vaccines be ineffective, but they may also be potentially harmful. Noteworthy, data from studies on patients with other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), on immunosuppressive and biologic therapies suggested that there were no significant defects in vaccine responses. Kapetanovic et al,14 however, reported that RA patients being treated with methotrexate (MTX) had an impaired immune response to pneumococcal vaccine, and this is consistent with the recognized inhibition of antibody responses with this agent. In IBD, Melmed et al15 recently reported that 20 patients treated with combination biologic and immunomodulator therapy had a lower response to pneumococcal vaccine compared to untreated patients or healthy controls. The present study was conducted in order to evaluate the effects of thiopurines on both cellular and humoral immune responses in IBD patients, in vivo and in vitro, specifically for the ability to mount an effective immune response to vaccines. Patients underwent a standard evaluation for evidence of immune deficiency before as well as 3 and 6 months after initiating therapy. No evidence for either an intrinsic or induced immunodeficient state was detected, supporting the concept that these agents are not global immunosuppressive agents at the doses used in the treatment of IBD.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

IBD patients referred for either AZA/6-MP treatment (naive to AZA/6-MP) were prospectively recruited. The indications for the initiation of therapy were either flare-up or postoperative prophylaxis. Recruitment was conducted in parallel at the IBD Centers at the Tel Aviv Medical Center (TASMC) and the Mount Sinai Medical Center (MSMC). Demographic and clinical data were obtained at recruitment, and included disease activity throughout the study (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI]16 and Mayo,17 respectively). The local Institutional Review Board (IRB) committees approved the study protocol and all patients signed an informed consent.

Just before initiating thiopurine therapy, patients were vaccinated intramuscularly with the diphtheria and tetanus toxoid vaccine (Wyeth Laboratories, Madison, NJ) and the Streptococcus pneumonia vaccine (Pneumovax 23, Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ). Pneumovax is a 23-valent preparation containing various capsular polysaccharides and response to this vaccine is used as the standard for determination for the requirement for intravenous gammaglobulin therapy in the presence of immune deficiency. At week 24, when the maximal effect of thiopurines would have been achieved, vaccination against Haemophilus influenza type B (HIB titer, Lederle Labs, Pearl River, NY) was administered.

Standard measures of immune competence were performed in all patients using established in vitro and in vivo assessments. Peripheral venous blood was obtained before (time 0) and during (3, 12, 24, and 27 weeks) therapy. Laboratory tests included standard laboratory tests, lymphocyte counts, and phenotypes as determined by flow cytometry. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were incubated with directly conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD14, CD56 as well as relevant isotype controls as previously described.

Lymphocyte proliferative responses to the mitogens concanavalin A (Con A), phytohemagglutinin (PHA), and to the antigens Candida and tetanus were performed using well-established methods.18,19 Response was assessed using thymidine incorporation by antigen or mitogen activation compared to unstimulated PBMC according to previously described protocols.18,19 The results, presented as fold increase over unstimulated control cell cultures, were compared to both the proliferative responses of healthy volunteers as well as to the patients’ own response at baseline. Total quantitative immunoglobulin (Ig) and IgG subclass levels were measured by a standard radial immunodiffusion assay comparing results to established normal standards.

The responses to vaccination in vivo (Pneumovax, tetanus toxoid, and HIB) were assessed using standard World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for immunodeficiency, comparing serum antibody titers to the relevant proteins (glycoproteins) before and 3 weeks after each vaccination and performed in a central laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ) using established values for normal healthy controls. The response to tetanus toxoid was defined as a 2-fold or greater increase in antibody titer over baseline following immunization. Pneumococcal response was defined as a 2-fold or greater increase in antibody titer over baseline to at least 4/14 serotypic determinants within the vaccine.19 The assessed serotypes were 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 14, 19, 23, 26, 51, 56, and 68 (American nomenclature). The response to HIB was defined as a greater than 2-fold increase in antibody titer (with at least a geometric mean titer of greater than 1 μg/mL, considered a protective level).

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and disease data were analyzed using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Differences between continuous variables at weeks 0, 12, and 24 were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, SPSS v. 16, Chicago, IL). Differences between the geometric mean concentrations in pre- and postvaccination serum samples were calculated by repeated measures of variance. Proportions were compared by χ2 analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 53 patients were recruited, 26 at the TASMC and 27 at the MSMC. Thirty-five patients had CD, 15 had UC, and three had indeterminate colitis (IC). Forty-three patients completed at least a 24-week course of therapy. The other 10 (19%) patients either withdrew due to thiopurine side effects or were lost to follow-up during the study period. In no case did the vaccination induce disease exacerbation. Patient demographics and data related to the specifics of the disease are presented in Table 1. All patients except for three were treated with 6-MP and not AZA. The average dose of 6-MP (AZA dose was converted to 6-MP) at the beginning of the study was 0.85 ± 0.35 mg/kg and 0.87 ± 0.34 mg/kg for CD and UC, respectively. After 6 months of treatment, the average 6-MP dose was 1.05 ± 0.30 mg/kg and 1.08 ± 0.49 mg/kg for CD and UC, respectively. There was a trend towards improvement in the CDAI in nine of the 19 patients (47%) for whom CDAI was detected over the 6-month period. This trend did not reach significance, very likely due to the inclusion of patients receiving thiopurine therapy for post-operative prophylaxis or maintenance of steroid-induced remission. The Mayo scores did not change significantly during thiopurine treatment.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Disease Data

| Crohn’s Disease n = 31 | Ulcerative Colitis n = 12 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender M/F | 21/10 | 4/8 |

| Age, y | 33.1 ± 11.2 | 35.6 ± 12.7 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 21.71 ± 6.9 | 29.00 ± 12.4 |

| Ashkenazi origin | 17 | 7 |

| Smoker | 3 (9.6%) | 0 |

| Disease duration, y | 12.1 ± 12.3 | 6.5 ± 7.9 |

| Concomitant | 5-ASA 14 (45%) | 5-ASA 6 (50%) |

| medical | Antibiotics 8 (26%) | Antibiotics 2 (17%) |

| treatment | Steroids 5 (16%) | Steroids 6 (50%) (P = 0.058) |

| Surgery | ||

| SBR | 10 | 0 |

| IPAA | 1 | 1 |

| Appendectomy | 0 | 1 |

SBR, small bowel resection; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.

Liver chemistries and mean hemoglobin levels remained within normal limits during treatment with thiopurines (data not shown).

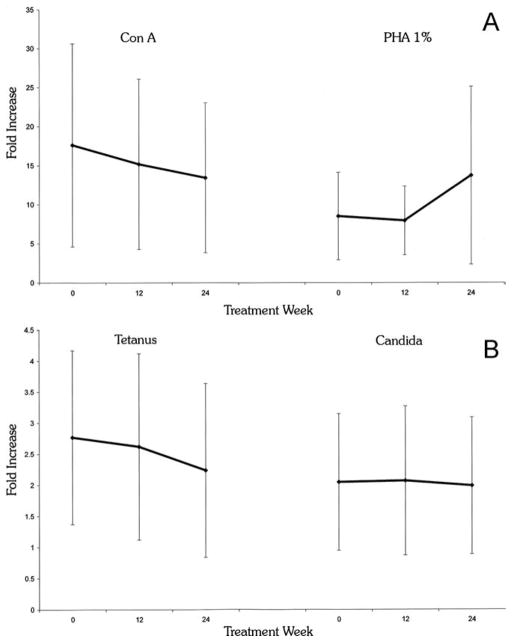

The major laboratory changes expected with thiopurine therapy are a decrease in the white blood cell (WBC) count and potential abnormal liver chemistries (LFTs). These were followed on a routine basis. Over the 24-week period there was a significant reduction in WBC count in both the CD (from 8.2 ± 3.0 103/μL to 5.6 ± 2.1 103/μL, P = 0.002) and the UC (from 8.5 ± 2.8 103/μL to 4.6 ± 0.8 103/μL, P < 0.001) patients. Importantly, this decrease was already noted at 12 weeks (but not 3 weeks) of treatment, in both the CD (6.0 ± 1.8 103/μL, P = 0.003 versus baseline) and the UC (5.0 ± 1.1 103/μL, P = 0.002 versus baseline) patients, supporting the slow onset of action associated with thiopurine therapy. There was no significant reduction in CD3 or CD4+ T-lymphocytes subpopulations in any of the IBD patients. On the contrary, the percentage of CD3 and CD4+ T cells actually increased during the 24 weeks of treatment: CD3 P = 0.05 and CD4 P = 0.025 (Fig. 1). The lowest WBC count seen at any point during follow-up was 2300/mm3. No patient was withdrawn during the study due to leukopenia, and no infectious complications associated with a decreased WBC count were seen.

FIGURE 1.

Lymphocyte subpopulations during the course of thiopurine therapy. Lymphocyte subpopulations were assessed at week 0, 12, and 24. Lymphocytes were incubated with directly conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD14, CD56 as well as relevant isotype controls. Gating on mononuclear cells or CD3+ populations, the percentage of positive cells was measured by flow cytometry. Values are percent ± SE. n = 22–33, P = 0.05 CD3 24 weeks versus 0, P = 0.025 CD4 week 24 versus 0.

Several groups have previously reported that total serum Ig levels and IgG subclasses are reduced in patients with IBD.20 This might correlate with an inability to mount an immune response and might even suggest a primary humoral immune defect in these patients. We therefore measured total quantitative Ig levels as well as IgG subclasses during the study period and found that the neither total Ig levels nor IgG subclasses, IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4, changed significantly over the course of thiopurine therapy (Tables 2, 3).

TABLE 2.

Quantitative Immunoglobulin Levels During Thiopurine Therapy

| Antibody Isotype (Normal Range) | Baseline Mean ± SD n = 49 |

12 weeks Mean ± SD n = 35 |

24 weeks Mean ± SD n = 33 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG (720–1350 mg%) | 1130 ± 377 | 1183 ± 344 | 1220 ± 346 | 0.35 |

| IgA (80–350 mg%) | 224 ± 126 | 233 ± 122 | 243 ± 114 | 0.29 |

| IgM (70–375 mg%) | 123 ± 79 | 118 ± 61 | 129 ± 87 | 0.5 |

TABLE 3.

IgG Subclass Levels During Thiopurine Therapy

| IgG Subclass (Normal Range) | Baseline Mean ± SD n = 49 |

12 weeks Mean ± SD n = 37 |

24 weeks Mean ± SD n = 28 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 455.9–892.6 mg/% | 600 ± 221 | 601 ± 196 | 630 ± 192 | 0.23 |

| IgG2 188.9–526.6 mg/% | 422 ± 230 | 467 ± 215 | 528 ± 216 | 0.017 |

| IgG3 16.8–99.8 mg/% | 66 ± 39 | 74 ± 38 | 76 ± 34 | 0.40 |

| IgG4 7.2–73.9 mg/% | 25 ± 20 | 26 ± 23 | 29 ± 21 | 0.66 |

Interestingly, there was a significant increase in IgG2 subclass levels among the IBD patients after 12 weeks and these remained significantly increased after 24 weeks of therapy (from 422 mg% to 467 mg% and 528 mg%, P = 0.005 and P = 0.017, respectively) which was largely due to an increase in the UC group (P = 0.02), but not the CD group (P = 0.30).

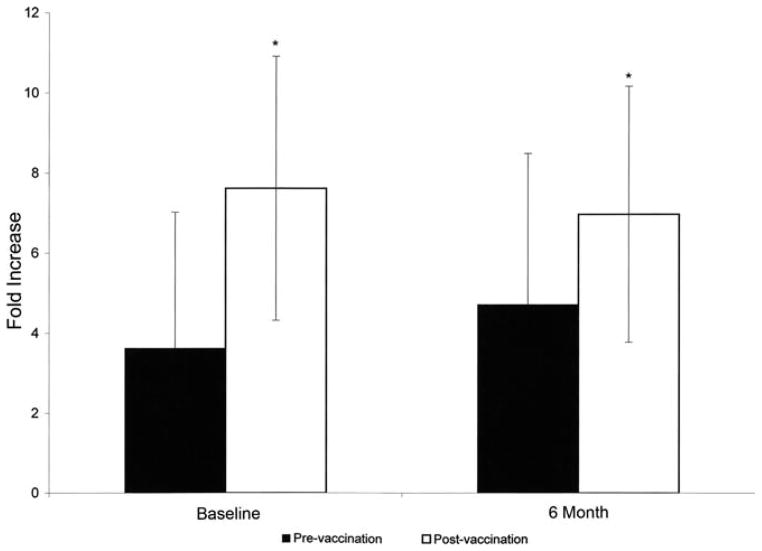

The integrity of T-cell function was measured as cellular proliferation (fold increase in 3H thymidine incorporation) in response to nonspecific mitogens (PHA and Con A) and specific antigens (tetanus and candida). These results were compared longitudinally for each patient as well as between patients and healthy controls. As seen in Figure 2, after 24 weeks of therapy there was no significant reduction in response to either stimulus versus baseline: tetanus: 2.24 ± 1.4 (week 24) versus 2.77 ± 1.44 (baseline) (P = 0.23), candida 1.99 ± 1.1 versus 2.05 ± 1.1 (P = 0.85), Con A 13.44 ± 9.6 versus 17.62 ± 13 (P = 0.22) and PHA 13.73 ± 11.4 versus 8.51 ± 5.6 (P = 0.10). The baseline responses to soluble antigen in the IBD patients were comparable for patients and controls, with a trend toward greater (not reduced) responses: tetanus 2.77 ± 1.44 versus 1.58 ± 0.73 (P < 0.001), candida 2.05 ± 1.1 versus 1.73 ± 0.57 (P = 0.21). For mitogens, the baseline responses compared to controls was Con A 17.62 ± 13 versus 22 ± 2.46 (P = 0.21), PHA 8.51 ± 5.6 versus 19.52 ± 2.2 (P < 0.001). Thus, not only was there little evidence for an inherent adaptive immune defect, but also there was no evidence to suggest that the thiopurine immunomodulators had affected T-cell-specific responses.

FIGURE 2.

Proliferative responses to mitogens and antigens. Peripheral venous blood was obtained before (time 0) and during (12 and 24 weeks) thiopurine therapy. Lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens (MG): Con A, PHA (panel A) and antigens (Ag): candida, tetanus (panel B) were determined after 72 and 96 hours of incubation, respectively, assessed by thymidine incorporation detected by a β-counter, and compared to the proliferative response at baseline and to that of healthy volunteers. Values are fold increase (FI) ± SE compared to the patient’s nonstimulated PBMCs. At week 24 versus baseline: P = 0.23 and P = 0.85 for tetanus and candida stimulation, respectively. P = 0.22 and P = 0.10 for Con A and PHA stimulation, respectively. At week 24 versus healthy controls: P < 0.001 and P = 0.20 for tetanus and candida stimulation, respectively. P = 0.21 and P < 0.001 for Con A and PHA stimulation, respectively.

The most important measure of immunologic integrity is a patient’s response to vaccination in vivo. Vaccine responses indicate the adequacy of antigen uptake, processing, presentation, and T- and B-cell activation and interaction. The patients in our study were immunized with tetanus toxoid (recall response) and Pneumovax (primary response) before initiating thiopurine therapy. There was a normal response to tetanus vaccine at baseline, with mean values significantly increasing after vaccination (from 2.2 ± 2.2 IU/mL to 5.7 ± 2.3 IU/mL, P < 0.01). Moreover, 27/37 patients (73%) had at least a 2-fold rise in antibody titer compared to baseline.

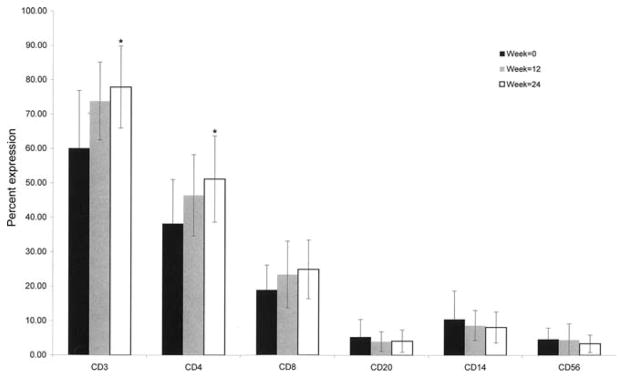

The mean values pre- and postvaccination with Pneumovax are presented in Table 4, and display a significant increase in titer to all pneumococcal serotypes. Importantly, 21/28 (75%) of patients vaccinated with Pneumovax had at least a 2-fold increase in pre- and postvaccination titers to at least 4/14 serotypic determinants—the definition of a response to Pneumovax—before starting thiopurine therapy. These data suggest that there is no intrinsic immunodeficiency in IBD patients. Patients were administered HIB vaccine following 24 weeks of thiopurine therapy with a significant increase in antibody titer: 4.72 ± 3.29 pre- versus 6.97 ± 3.19 IU/mL postvaccination at 27 weeks (P = 0.009, n = 19). A subgroup of nine patients had been previously immunized with HIB and they expressed a significant increase in titer, from a mean of 3.63 ± 3.4 at baseline to 7.62 ± 3.7 IU/mL at 3 weeks (P = 0.008). Thus, a significant increase in response to HIB vaccine was observed in both immunomodulator-naïve versus immunomodulator treated IBD patients (Fig. 3). These data provide convincing evidence for an intact immune system in IBD patients both before and after initiating thiopurine therapy.

TABLE 4.

Serologic Response to Pneumovax

| Serotype | Mean Levels IU/mL Baseline n = 34 |

Mean Levels IU/mL 3 Weeks n = 33 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.7 ± 1 | 10.1 ± 19.6 | 0.026 |

| 3 | 2.5 ± 4.1 | 6.9 ± 7.8 | 0.003 |

| 4 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 7.0 ± 11.0 | 0.003 |

| 5 | 2.4 ± 4.5 | 16.2 ± 25.5 | 0.005 |

| 8 | 15.2 ± 24.5 | 29.4 ± 29.9 | 0.002 |

| 9 | 6.3 ± 16.7 | 18.7 ± 23.6 | 0.000 |

| 12 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.000 |

| 14 | 3.8 ± 11.9 | 20.7 ± 27.6 | 0.001 |

| 19 | 1.6 ± 2.6 | 21.4 ± 35.9 | 0.005 |

| 23 | 9.0 ± 21.9 | 15.3 ± 25.8 | 0.038 |

| 26 | 6.4 ± 13.8 | 19.8 ± 30.5 | 0.035 |

| 51 | 9.2 ± 25.3 | 23.8 ± 37.9 | 0.007 |

| 56 | 5.2 ± 11.7 | 17.9 ± 27.7 | 0.013 |

| 68 | 2.1 ± 2.6 | 6.0 ± 8.6 | 0.006 |

FIGURE 3.

Response to HIB vaccine in thiopurine-naïve and thiopurine- treated IBD patients. IBD patients were vaccinated with HIB vaccine either at baseline (thiopurine-naïve, n = 9, left bars) or after 6 months of therapy (thiopurine-treated, n = 19, right bars). Serum antibody titers before and 3 weeks after vaccination were detected. Values are mean IU/mL ± SE. P = 0.009 for pre- versus postvaccination in thiopurine-naïve patients, P = 0.008 for pre- versus postvaccination in thiopurine-treated patients.

Importantly, in the subgroup of patients who were treated with 6-MP doses higher than 1.1 mg/kg, the response to HIB vaccine was 8.5 ± 1.73 IU/mL compared to 6.4 ± 3.7 IU/mL in the group treated with lower doses (P = 0.04). Total IgG levels were also similar (P = NS). Thus, there was no evidence for decreased in vivo humoral immune responses even when higher 6-MP doses were used.

DISCUSSION

Immunomodulatory drugs are increasingly used in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Questions are still raised about the extent of their immunosuppression and their mechanism of action. Most data relating to the assessment of immune function while on thiopurines have come from studies performed on patients with hematological malignancies, for which the dose is higher or inherent defects in immune function exist. Few attempts have been made to define immune function at the doses used for treating IBD and vaccine responses in patients with IBD have only been studied in part.15 The data published to date suggest that responses might be subpar, and attempts have been made to link this feature to the use of thiopurines. A recent review11 noted that the guidelines and recommendations for vaccination in patients with IBD are based on limited data and extrapolation from other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Interestingly, studies in the rheumatologic patient population have shown adequate vaccine responses in patients on a variety of immunomodulatory drugs (e.g., MTX, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept). Several authors have, however, noted reduced responses to specific vaccines in certain diseases (e.g., RA) with specific treatments, such as MTX or infliximab. 14 Limited data are available on vaccine responses in IBD patients taking thiopurines. Melmed et al’s recent study15 in 24 IBD patients treated with a combination of biologics and immunomodulators demonstrated an impaired response to pneumococcal vaccine in a subgroup of patients, as defined by their inability to mount a 2-fold rise and achieve protective (1 μg/mL) in antibody titers. Of note, those authors measured responses to only five serotypes, not the conventional panel of 14 serotypes, thus increasing the chances of missing normal responses to these other serotypes. It is well recognized that there is wide variation in response to different serotypes within a normal control population. More important, the 17 patients in their study who were treated with immunomodulators were all being concomitantly treated with biologics, making it impossible to differentiate between the effects of the two.

The current study was specifically designed to assess immune function in patients with IBD in vitro and in vivo before and after initiating immunomodulator therapy, using the standard evaluation for suspected immunodeficiency. The main goal was to assess whether patients receiving thiopurines immunomodulators are immunosuppressed as measured by their ability to mount an adequate immune response to vaccines. We also evaluated whether vaccines that act to stimulate the immune system might cause an exacerbation of IBD, given that there is an inherently overactive immune response in the mucosa. Each of our patients served as his or her own control, and changes in lymphocyte numbers, Ig levels, T-cell responses to antigens and mitogens and, most important, in vivo antibody responses, were assessed. Several important findings emerged from these assessments. First, patients with IBD had normal baseline adaptive immune function. We found normal baseline Ig levels, normal lymphocyte numbers, and normal responses to in vitro stimulation with antigens and mitogens. In addition, and more relevant to the assessment of immune function, the response to two distinct vaccines was completely normal at baseline. It should be noted that many of the patients who entered this study had active disease requiring the addition of antimetabolite therapy. Systemic immune function was normal even in the presence of active inflammation in the bowel.

The only significant change observed during the course of thiopurine therapy was leukopenia, which was noted in all patients. There were no significant decreases in lymphocyte subpopulations (CD3 and CD4+ T cells actually increased in percentage), total quantitative Ig and IgG subclass levels, and antigen and mitogen responses. The response to HIB vaccine administered 24 weeks following initiation of thiopurines increased significantly, and it was comparable to the response to HIB in immunomodulator-naïve patients.

Moreover, after 24 weeks of thiopurine therapy there was no significant decrease in response to HIB vaccine between patients receiving higher, compared to relatively lower thiopurine doses. It can therefore be concluded that thiopurines did not suppress this aspect of immune function in vivo.

Furthermore, similar to reports from the rheumatologic literature,22 we did not observe any increase in disease severity that could be attributable to vaccination. Based on these findings, we conclude that vaccines are safe in IBD patients, even when the disease activity is high. We conclude, therefore, that no significant humoral immunodeficiency or disease exacerbation is induced in IBD patients who receive immunomodulators.

In patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) or other forms of immunodeficiency, the decision to treat with intravenous Ig replacement therapy hinges on the response/nonresponse to vaccines such as Pneumovax. This vaccine contains antigenic determinants from 14 serotypes of Streptococcus pneumonia. The response to some serotypes is T-cell-dependent (3, 9, 14, and 23), whereas others elicit a T-cell-independent response (B cell). Thus, this vaccine assesses both T- and B-cell function in vivo. In contrast, both HIB and tetanus are protein vaccines and therefore highly T-cell-dependent.23 It is important to note that our patients demonstrated normal responses to both T-cell-dependent and T-cell-independent antigens, and there is little evidence for inherent adaptive immune deficiency in this patient population whether before or after thiopurine therapy.

Similar studies in patients with rheumatologic diseases (RA, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], and psoriasis) have addressed responses to pneumococcal vaccine in those receiving MTX, prednisone, azathioprine, infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept. Elkayam et al22 reported that while generally immune responses to Pneumovax in RA patients were similar to controls, the vaccine was not uniformly immunogenic and 33% of RA patients responded to none or only one of seven serotypes tested. A poor vaccine response was not associated with the use of any specific immunosuppressive agent in that study,22 including prednisone >10 mg, MTX, or AZA.

Only a few studies have thus far addressed the response to vaccinations in IBD patients. Mamula et al24 compared 51 children with IBD and 29 healthy controls during the 2002–2004 influenza seasons, and reported that the IBD group mounted less effective responses to one-third of antigens compared to controls, while patients on combination anti-TNFα and immunomodulators had impaired responses to two-thirds of antigens. In contrast, Lu et al25 assessed response rates in 146 children with IBD vaccinated against influenza in 2007 and reported that responses were similar among IBD patients, regardless of immunosuppressive status. Of note, none of these studies separated the effect of immunomodulators from that of biologics, or assessed other immune functions.

Recent studies have suggested that the thiopurines work by the intercalation of the Ras pathway downstream of the T-cell receptor,4 causing disrupted T-cell function during activation. Others have shown that the thiopurines do not interfere with T-cell effector cell function (cytokine production),26 but rather that thiopurine treatment resulted in the depletion of antigen-specific memory T cells, dependent on repeated encounters with the antigen. Thus, it is plausible that T-cell activation in response to vaccination could still occur while on these agents. We did not observe any significant phenotypic changes in memory cell subpopulations (data not shown). However, given that T-cell function was maintained after thiopurine treatment, our study results support that somewhat provocative possibility.

In conclusion, this study is one of the first to directly address the specific effect of thiopurine immunomodulatory drugs on intact (in vivo) cellular and humoral immune responses in IBD patients. We were able to demonstrate that there is no intrinsic immune deficiency associated with IBD and, more important, that IBD patients treated with thiopurines are able to mount an effective immune response. The practical implication of these findings is that IBD patients on thiopurines may be safely and effectively vaccinated. This is especially important for the ones who travel frequently and require vaccinations against life-threatening diseases. The recently published ECCO guidelines address the issue of bacterial infections (specifically pneumonia), and recommend that patients should be vaccinated prior to commencing immunomodulator therapy (12). Based on the data described in this current investigation, we propose that vaccination can safely and effectively be given after immunomodulator therapy has been initiated. Finally, it is our position that thiopurines are immunomodulators, rather than global immunosuppressors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Esther Eshkol, the institutional medical and scientific copyeditor, for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:981–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prefontaine E, Sutherland LR, Macdonald JK, et al. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD000067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000067.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaye OA, Yadegari M, Abreu MT, et al. Hepatotoxicity of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and azathioprine (AZA) in adult IBD patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2488–2494. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiede I, Fritz G, Strand S, et al. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target of azathioprine in primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1133–1145. doi: 10.1172/JCI16432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, et al. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081–1085. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombel JF, Ferrari N, Debuysere H, et al. Genotypic analysis of thiopurine S-methyltransferase in patients with Crohn’s disease and severe myelosuppression during azathioprine therapy. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toruner M, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:929–936. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glazier KD, Palance AL, Griffel LH, et al. The ten-year single-center experience with 6-mercaptopurine in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aberra FN, Lichtenstein GR. Methods to avoid infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:685–695. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000160742.91602.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korelitz BI, Fuller SR, Warman JI, et al. Shingles during the course of treatment with 6-mercaptopurine for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:424–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.871_w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sands BE, Cuffari C, Katz J, et al. Guidelines for immunizations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:677–692. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahier JF, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, et al. European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2009;3:47–91. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melmed GY, Ippoliti AF, Papadakis KA, et al. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are at risk for vaccine-preventable illnesses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1834–1840. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapetanovic MC, Saxne T, Sjöholm A, et al. Influence of methotrexate, TNF blockers and prednisolone on antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:106–111. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melmed GY, Agarwal N, Frenck RW, et al. Immunosuppression impairs response to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:148–154. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone KD, Feldman HA, Huisman C, et al. Analysis of in vitro lymphocyte proliferation as a screening tool for cellular immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2009;131:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pacheco SE, Shearer WT. Laboratory aspects of immunology. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1994;41:623–655. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gouni-Berthold I, Baumeister B, Berthold HK, et al. Ig and IgG subclasses in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1720–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkayam O, Caspi D, Reitblatt T, et al. The effect of tumor necrosis factor blockade on the response to pneumococcal vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;33:283–288. doi: 10.1053/j.semarthrit.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkayam O, Paran D, Caspi D, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of pneumococcal vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:147–153. doi: 10.1086/338043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noroski LM, Shearer WT. Screening for primary immunodeficiencies in the clinical immunology laboratory. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;86:237–245. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Piccoli DA, et al. Immune response to influenza vaccine in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Jacobson DL, Ashworth LA, et al. Immune response to influenza vaccine in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:444–453. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Horin S, Goldstein I, Fudim E, et al. Early preservation of effector functions followed by eventual T cell memory depletion: a model for the delayed onset of the effect of thiopurines. Gut. 2009;58:396–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]