To the Editor:

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common and debilitating problem that involves inflammation of the mucosal surfaces lining the nose and sinuses.1 Triggers leading to CRS disease exacerbation are not well characterized. Previous epidemiologic studies have focused on identification of risk factors for having a diagnosis of CRS rather than on risk factors that lead to disease exacerbation in those with an established CRS diagnosis.2 and 3 Given the insights gained from examining seasonal patterns of asthma exacerbations (a disease often linked to CRS),4 we performed a study that examined the seasonal pattern of CRS exacerbation visits using a unique database that electronically links residents of a single county in southeastern Minnesota (Olmsted County).

We performed a retrospective cohort study following patients for up to 2 years (2003–2004) using existing medical records. Patients were identified by using the Rochester Epidemiology Project, an electronically linked medical record system that allows for examination of nearly all health care encounters in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Both sexes and all ages were included. Patients with a diagnosis of specific immune deficiency were excluded. A CRS exacerbation was defined as any visit with an International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Revisions (ICD-9) code of 473.xx and at least 1 of the following: a prescription for systemic antibiotics, systemic corticosteroid, plans for a semiurgent surgical intervention, emergency department or urgent care visit, or a hospitalization for CRS. Each medical record was reviewed to ensure subjects met inclusion criteria and that the prescribed medications were directly linked with the diagnosis of CRS. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Olmsted Medical Center and Mayo Clinic Rochester.

Descriptive statistics were tabulated for subject demographics and visit frequencies. Seasonality was confirmed by defining 4 equal-length calendar seasons and comparing visit frequencies for equality across seasons with a χ2 test. For graphic displays, visit frequencies were smoothed by using a kernel smoother with a Parzen kernel and a bandwidth chosen empirically.

One thousand one hundred four patients with a diagnosis of 473.xx were screened, and 800 patients had at least 1 visit that met our definition of a CRS exacerbation. Most subjects were female (65.6%) and white (94%). The mean age of the patients was 37 years, with 17.8% of the subjects defined as children (<18 years old). A total of 1217 CRS exacerbation visits were analyzed. The number of visits per subject over 2003–2004 ranged from 1 to 16, and 607 (75.9%) patients had only 1 CRS exacerbation visit. Primary care provider visits accounted for 55.7% of the visits, whereas allergy (13.7%), otolaryngology (13.1%), and emergency department/urgent care (13.1%) accounted for the nearly all of the remaining visits.

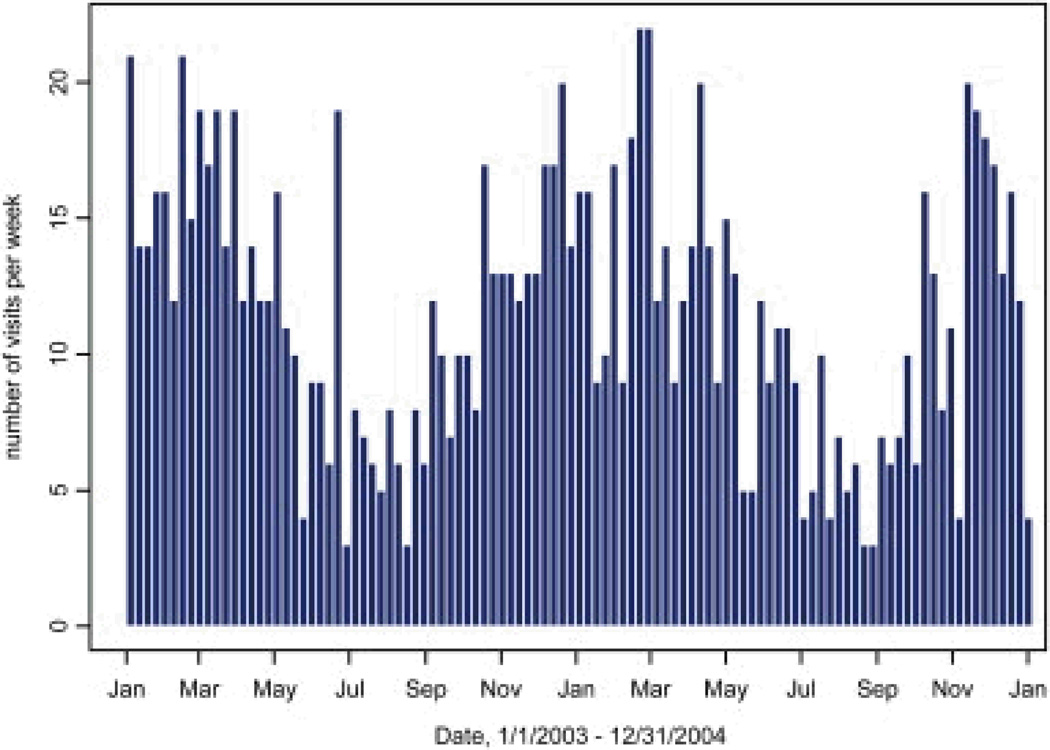

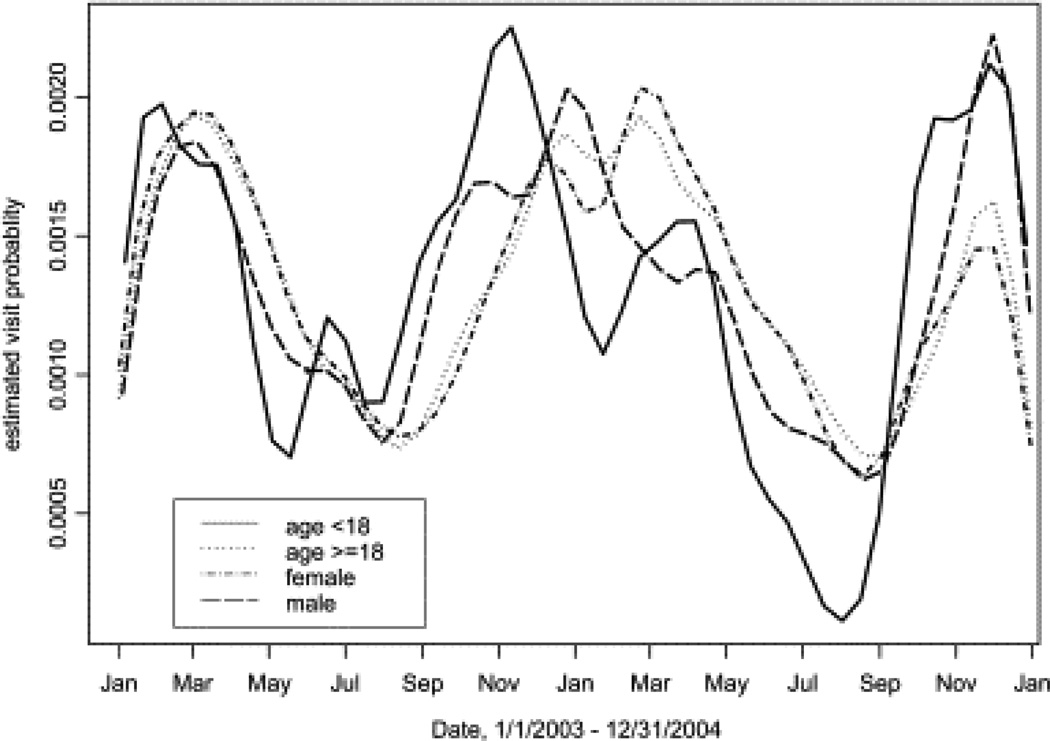

Subjects were approximately twice as likely to present for a CRS exacerbation in winter months compared with spring, summer, or fall (P < .0001, Fig 1). The seasonal pattern of increased CRS exacerbation visits in winter was consistent between 2003 and 2004. Age and sex did not significantly affect the seasonal pattern of CRS exacerbation visits, although in both 2003 and 2004, the CRS exacerbation visit frequency of children began to increase earlier (more in fall than winter) compared with that seen in adults (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Seasonal pattern of CRS exacerbation visits (n=1217). Each bar represents 1 weeks

Fig 2.

Seasonal pattern of CRS exacerbation visits by age and sex

The findings from this study suggest that patients with CRS are most likely to present for disease exacerbation in the winter months in the upper Midwestern United States than in spring, summer, or fall seasons. Using the linked electronic medical record system in Olmsted County, Minnesota, we were able to use a definition of disease exacerbation that is based on health care use (escalating management, mostly prescriptions for systemic antibiotics or systemic corticosteroids) rather than billing data alone.

There are important limitations when interpreting the data from this study. Screening patients based on ICD-9 codes relies on clinician billing diagnosis rather than an objective set of criteria. A risk for diagnostic misclassification exists, in particular that the increased winter visit frequency represented viral upper respiratory tract infections uncomplicated by sinusitis. The potential for this bias to occur is difficult to measure with our study design, and even if sinus computed tomographic scans were available from each visit, they might be difficult to interpret given that previous research has demonstrated that uncomplicated upper respiratory tract viral infections frequently result in significant sinus computed tomographic findings.5

A consensus definition of an acute exacerbation of CRS is not available. Therefore although we recognize that a surgical intervention and a prescription for antibiotics might represent different impressions of disease severity, we believed that evidence of management escalation was the best possible measurement that an exacerbation of CRS had occurred in our dataset. Another limitation of this study is that generalizing findings to other climates is difficult. Finally, the ethnic diversity in our sample might not represent other CRS populations well, and ethnic differences in the inflammatory characteristics of CRS have been demonstrated.6 Despite these limitations, we believe that these data uncovered a strong signal that patients with CRS exacerbations are more likely to visit for disease worsening during winter months.

Several plausible hypotheses arise from these findings, including a potential relationship between CRS disease activity and viral infection, air quality, air temperature, air humidity, or indoor allergen/irritant exposure. These findings are important because they direct future research toward previously understudied explanations for CRS exacerbations. Data from this study also might help clinicians anticipate an increased need for CRS disease management during winter months.

Acknowledgements

We thank Linda Paradise, RN, and Christine Pilon-Kacir, RN, PhD, for their assistance with data abstraction. We also thank the Rochester Epidemiology Project and its funding source (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases RO1 AR30582).

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: M. A. Rank has received research support from PureZone, Inc. The rest of the authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pleis JR, Coles R. Summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 1998. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2002;10:1–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Dales R, Li M. The epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Canadians. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1199–1205. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Min Y-G, Jung H-W, Park SK, Yoo KY. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic sinusitis in Korea: results of a nationwide survey. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253:435–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00168498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston NW, Johnston SL, Norman GR, Dai J, Sears MR. The September epidemic of asthma hospitalization: school children as disease vectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:557–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Phillips CD, Miller RD, Riker DK. Computed tomography study of the common cold. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:25–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401063300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang N, Van Zele T, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene H, Holtappels G, DeRuyck N, et al. Different types T-effector cells orchestrate mucosal inflammation in chronic sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]