Abstract

This paper describes an integration of the stereotype content model with social identity theory in which we theorise links between the legitimacy and stability of status relations between groups on the one hand, and stereotypes of warmth and competence on the other. Warmth stereotypes associate with the perceived morality of inequalities, so we reason that high and low status groups are more differentiated in warmth in illegitimate status systems. Also, stereotypes of competence explain status differences, so differences in stereotypical competence may be more pronounced when status is stable rather than unstable. Across two experiments high and low status groups were more sharply differentiated in warmth in illegitimate than legitimate status systems, as predicted. The effect of stability on competence was less clear, as groups were clearly differentiated in competence in all status systems. Implications for the roles of warmth and competence stereotypes in social change are discussed.

In recent years research on social stereotypes has uncovered basic dimensions on which groups tend to be differentiated: competence and warmth (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2008). Most stereotypes convey a group’s perceived competence (e.g. motivated, powerful, intelligent, efficient) and warmth (e.g. trustworthy, sincere, friendly, moral). Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and colleagues (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2007, 2008; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2006; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002), in their stereotype content model (SCM) and Behaviour from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes (BIAS) map, argue these stereotypes capture important types of intergroup relationships and prejudices. Outgroups stereotyped as competent but cold, such as rich people and feminists, are envied and avoided; those characterised as incompetent but warm, including elderly and disabled people, are pitied and helped; and those stereotyped as both incompetent and cold, such as social outcasts, addicts, and homeless people, are despised and excluded. Being competent and warm is a combination generally reserved for society’s prototypes and ingroups, who are respected and admired.

Another general theory of intergroup relations, social identity theory (SIT), characterises intergroup relations in terms of the structural variables of status stability, legitimacy and permeability. These variables determine whether groups are likely to accept social inequalities and adopt belief systems that justify them, or reject inequalities and challenge the status quo (see also Leach, Snider, & Iyer, 2002). For example, Blacks and women began to fight for equal rights only when they came to see race and gender inequalities as illegitimate and change as a real possibility. A connection between the SCM and SIT becomes apparent here because part of the process of social change involves a change to stereotypes, particularly stereotypes of competence and warmth. One reason that Herrnstein and Murray’s (1994) book ‘The Bell Curve’ was so controversial was that it provided intellectual support to stereotypical differences in intelligence between races, which justified and stabilised racial inequalities. Hence, both the SCM and SIT seek to explain the psychological foundations of major types of intergroup relationships, but each focuses on different mechanisms—the SCM on stereotypes and SIT on structural variables.

To date there have been few attempts to bring these two approaches together, to theorise how stereotype contents might be systematically related to the broader social context surrounding status inequalities, defined in SIT through legitimacy and stability (but see Oldmeadow & Fiske, 2010, for an example). Given the overlap in the explanatory domains of the SCM and SIT it seems reasonable to suppose there may be close relationships between stereotypes of competence and warmth and particular kinds of social relationships defined in terms of legitimacy and stability. For example, a consensual difference in stereotypical competence between groups may be indicative of a stable status relationship since the stereotype both describes and justifies status differences. Stereotypes of warmth, on the other hand, may be linked particularly to legitimacy since stereotypes of (lack of) warmth signal competition between groups and also justify harsh treatment and exclusion of outgroups. Hence, combinations of competence and warmth stereotypes may align with intergroup relationships varying in legitimacy and stability.

In this paper we attempt to formally connect different combinations of competence and warmth stereotypes to different combinations of legitimacy and stability of intergroup relations. We outline a theoretical model of different status systems varying in legitimacy and stability, and describe the stereotypes likely to characterise groups within them. We then present two studies testing hypotheses derived from the model.

A model of status systems and associated stereotypes

In social psychology, hierarchical social arrangements at societal, intergroup, and interpersonal levels are often characterised in terms of legitimacy and stability (Ridgeway & Berger, 1988; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Tyler, 2006). Legitimacy refers to how fair or just a status system is believed to be, whereas stability refers to how enduring it is or is likely to be. These concepts play an important role in theories of compliance (Tyler & Lind, 1992), intergroup relations (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Tajfel & Turner, 1986), and status processes (Ridgeway & Berger, 1988). In social identity theory, for example, legitimacy and stability (along with permeability) are conceptualized as collective belief systems that determine whether groups accept their positions and acquiesce to social inequalities or seek to change the system and/or their place within it (Bettencourt, Dorr, Charlton, & Hume, 2001; Ellemers, 1993; Leach, et al., 2002; Spears, 2002). According to social identity theory, groups are most likely to accept social inequalities if they are legitimate and stable, and this is maximized if intergroup boundaries are permeable for individuals (Wright, 2001). From this and other theoretical perspectives, legitimacy and stability are critical in understanding the attitudes, behaviours and stereotypes of groups within hierarchical social systems.

How might the stability and legitimacy of status relations affect stereotypes of competence and warmth? Relationships between stability, legitimacy, competence and warmth are likely to be complex, but we predict that stability will primarily influence competence stereotypes and legitimacy will primarily influence warmth. Stereotypes of competence can be understood as group-level dispositional attributions for status, and dispositional attributions are more likely when an actor’s behaviour (or in this case status) is stable across situations (Kelley, 1967). Therefore, high and low status groups may be more differentiated in competence when status relations are stable compared to unstable. On the other hand, stereotypes of warmth relate to a groups’ perceived morality (Wojciszke, 2005), and also differentiate whether we feel pity or disgust, admiration or envy towards outgroups (Cuddy, et al., 2007). Therefore, warmth may be more strongly tied to the legitimacy of status relations. We expect high and low status groups will be more differentiated in warmth when status relations are illegitimate compared to legitimate.

Conceptualised in binary terms, combining stability and legitimacy produces four status systems, each associated with a distinct pattern of competence and warmth stereotypes. We refer to these four status systems as Content, Dynamic, Cynical, and Resentful.

Content: A Content climate is characteristic of legitimate and stable status relations. High status groups have gained their status legitimately and retained it for a long period of time. There is no consensual desire or hope for change. An example of this system might be Thailand where the King, Bhumibol Adulyadej, has been revered by the public and the world’s longest-serving head of state (Handley, 2006). Another example could be the Indian caste system, particularly prior to British colonization. Supported by religious beliefs, the caste system organized one of the world’s largest populations into a strict hierarchy for 1500 years. In such systems we can expect status groups to be sharply differentiated in competence, with high status groups stereotyped as considerably more competent than low status groups, but relatively undifferentiated in warmth because status relations themselves are essentially non-competitive or at least amicable.

Dynamic: A Dynamic climate emerges in status systems that are legitimate but unstable. High status groups have attained their position legitimately and are accepted as the current legitimate authority, but their status is likely to be temporary. They have not always enjoyed high status and they are likely to lose it again in the foreseeable future. A significant portion of the population may desire and work towards change. Most modern democracies would fit this pattern, as do most sports leagues. There is strong competition for status or power, which is awarded in accordance with a consensual set of rules and criteria. In this system high and low status groups should be relatively undifferentiated in competence because status positions are changeable. High and low status groups should be undifferentiated in terms of warmth since competition between them will be amicable.

Cynical: A Cynical climate surrounds status relations that are both illegitimate and unstable. High status groups are seen to have used illegitimate means to gain status or power (e.g. force, coercion, cheating), but they are unlikely to be able to hold onto it. Their status may have been short-lived historically and there is a strong desire and hope for change in the foreseeable future. An example might include Pakistan, in which no elected government has succeeded in seeing out its term, and leaders are often assassinated. The cultural climates surrounding the recent uprisings in Egypt and Libya, where leaders came to be seen as illegitimate and were forced out of power, could also be described as cynical. High and low status groups should be relatively undifferentiated in competence on account of status instability, but sharply differentiated in warmth with the high status group seen as particularly cold on account of their illegitimate actions.

Resentful: Status relations that are illegitimate yet stable correspond to Resentment. Those in power have attained their position through illegitimate means, but are able to maintain their position over a long period of time. Although there is likely to be a strong desire for change, there is little hope. Examples include any number of dictatorships, from Kim Jong-il in North Korea to Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe. In this system high status groups are likely to be seen as very low in warmth, though they will still be perceived as competent for being able to gain and hold their position. Low status groups should be characterized as lacking competence but excelling in warmth. Thus, status groups should be sharply differentiated in both competence and warmth in Resentful systems.

Table 1 presents a summary of the four status systems and the patterns of differentiation predicted by the model. These four status systems derive from combinations of status stability and legitimacy, and their predicted effects on competence and warmth stereotypes respectively. Although we have illustrated these systems with societal examples, we do not maintain that they apply only at the level of society. The cultures in organisations, institutions, and even some informal groups may be described as Content, Dynamic, Cynical or Resentful. At the same time we do not presume to have presented an exhaustive taxonomy of social systems, but rather one based on the major variables employed in relevant social-psychological theories (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Jost, Banaji, & Nosek, 2004; Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

Table 1.

The Four Status Systems Defined by Status Stability and Legitimacy and Predicted Patterns of Stereotypes

| Stable | Unstable | |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Dynamic | |

| Legitimate | E.g. caste systems Differentiated in competence but not in warmth |

E.g. democracies Differentiated in neither competence nor warmth |

| Resentful | Cynical | |

| Illegitimate | E.g. dictatorships Differentiated in both competence and warmth |

E.g. civil uprisings Differentiated in warmth but not in competence |

To summarise, we propose that status stability and legitimacy moderate stereotypes of competence and warmth respectively, producing four status systems characterized by distinct combinations of stereotypes. Specifically, we hypothesise that high and low status groups will be more differentiated in competence when status is stable rather than unstable, and more differentiated in warmth when status is illegitimate than when it is legitimate. Accordingly, we hypothesize that groups will be clearly differentiated on both competence and warmth in Resentful systems, and relatively undifferentiated on both dimensions in Dynamic systems. In Content systems groups will be differentiated on competence but not warmth, and in Cynical systems on warmth but not competence.

Study 1

An experimental study examined patterns of competence-warmth stereotypes within the four social systems defined by legitimacy and stability. In order to maintain maximum control over participants’ knowledge or perceptions of the relations between groups, we used a scenario describing two fictitious groups that differed in status, systematically varying legitimacy and stability in a between-participants design.

Method

Participants and Design

University students, 136 male and 207 female (n=345, two not specified), participated in the study. Age ranged from 18 to 59 years (M = 20.6, SD = 3.9). Several female experimenters approached participants in public places around campus and asked them to participate in the study by completing a questionnaire. Those who agreed to participate were handed one randomly selected version of the questionnaire, comprising one condition of a 2 (target group: high status vs. low status) by 4 (status system) mixed design with repeated measures on the first factor.

Materials and Procedure

Participants read a description of a fictitious society comprising two groups, Marpurs and Taipurs, that differed in socio-economic status. Four versions of the scenario orthogonally varied the legitimacy and stability of status relations. The first page of the questionnaire introduced the study as investigating “perceptions of group members,” explaining that it aimed to examine people’s perceptions and impressions of others who belong to different types of groups. Participants were informed that they would be asked to read a description of a fictitious society and answer questions about it. The remaining information dealt with issues of informed consent.

The scenario described a society (the Turithians), comprising two groups, Marpurs and Taipurs, that differed in socioeconomic status. In all conditions, the Marpurs were said to enjoy greater wealth, luxury, and health than Taipurs, and to have more prestigious jobs, earn more money, and have a better quality of life than Taipurs. The manipulations of legitimacy and stability followed this description. Stability was manipulated by informing participants that the Taipurs had never had higher social, economic, or political status than Marpurs and were unlikely to in the future (stable), or that the Marpurs had not always been higher in status and that the situation was likely to change again in the future (unstable). Legitimacy was manipulated by describing the means by which the Marpurs came into power, either through a fair democratic election (legitimate) or by rigging elections and using whatever means necessary to further their own wealth and power (illegitimate).

Participants responded to a series of questions using 7-point scales anchored at 1 with ‘Not at all’ and at 7 with ‘Extremely.’ The first set of questions related to participants’ perceptions of the socioeconomic differences between the groups, the legitimacy and stability of the status difference, and the degree of competition between the groups. On a separate page, participants rated the Marpurs and Taipurs on competence and warmth. For each group, three items measured competence (competent, capable, intelligent) and three measured warmth (friendly, warm, sincere). The three competence items were combined into single scores for each group (alphas > .85), as were the three warmth items (alphas > .89).

Results

Manipulation Checks

A 2 (target group: high status vs. low status) by 2 (stability) by 2 (legitimacy) mixed ANOVA on ratings of each group’s status revealed a highly significant main effect of target group, F (1, 341) = 903.12, p < .001, η2 = .73, confirming the status manipulation was successful. A univariate ANOVA on legitimacy ratings revealed a highly significant effect of status system, F (1, 341) = 149.98, p < .001, η2 = .31. A Tukey post hoc test showed the Resentful (M = 2.37) and Cynical (M = 2.81) systems were rated significantly lower in legitimacy than the Content (M = 4.01) and Dynamic (M = 4.38) systems. The legitimacy manipulation was therefore successful. Finally, there was a highly significant effect of the stability manipulation on perceived stability, F (1, 341) = 145.55, p < .001, η2 = .30, with the Dynamic (M = 4.91) and Cynical (M = 4.92) systems perceived as more unstable than the Resentful (M = 3.02) and Content (M = 3.10) systems. The manipulation of stability was therefore also successful.

Differentiation in competence and warmth across status systems

To assess whether the two groups were differentiated on competence and warmth in each status system, ratings of the high and low status groups on each stereotype dimension were compared using four separate 2 (target group: high versus low status) by 2 (stereotype dimension: competence versus warmth) ANOVAs. These ANOVAs were followed up with simple main effects analyses comparing high and low status groups on each stereotype dimension.

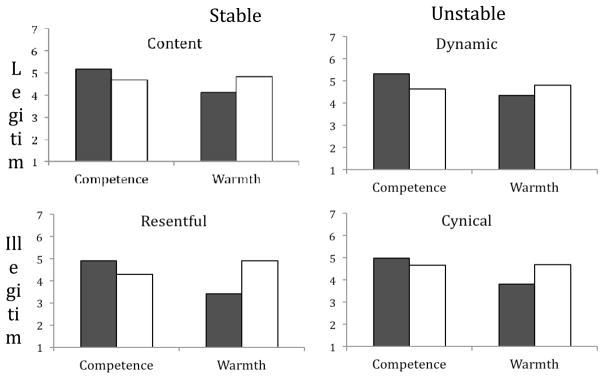

Consistent with the SCM the high status group was rated higher in competence and lower in warmth than the low status group in all status systems (see Figure 1). The group by stereotype dimension interaction was highly significant in each status system (Fs > 38.95, ps < .001, η2 > .31). Simple main effects confirmed that the high status group was rated significantly higher in competence than the low status group in all status systems (Fs > 9.73, ps < .002, η2 > .10), and the low status group was rated higher in warmth in all status systems (Fs > 18.38, ps < .001, η2 > .16).

Figure 1.

Competence and warmth ratings of the high status (black bars) and low status (white bars) groups as a function of status stability and legitimacy (Study 1).

To test the hypotheses that groups would be more differentiated in competence in stable systems and more differentiated in warmth in illegitimate systems, differentiation scores were created by subtracting the lower rated group from the higher rated group on each dimension. These were then analysed with 2 (legitimacy) by 2 (stability) ANOVAs. There were no main effects of either legitimacy or stability on differentiation in competence, Fs < 1, ns, and the interaction was also non-significant, F (1, 340) = 3.13, p = .078. For differentiation in warmth there were significant main effects of both legitimacy, F (1, 338) = 14.41, p < .001, η2 = .04, and stability, F (1, 338) = 7.55, p = .006, η2 = .02. Groups were more differentiated in warmth in illegitimate than legitimate status systems, as hypothesized, but also more differentiated in stable than unstable systems.

Discussion

Study 1 provided mixed support for our hypotheses. The groups were more differentiated in warmth in illegitimate systems—Cynical and Resentful—than in legitimate systems—Content and Dynamic—as predicted. However, they were also more differentiated in warmth in stable than unstable systems, and so were most differentiated in warmth in the Resentful system overall. Although we predicted groups to be more differentiated in competence in stable than unstable systems, there was no support for this. Instead, groups were equally differentiated in competence across all status systems.

The effects of stability on warmth were unexpected, but not unintelligible. Change is a normal part of the socio-political system for our participants who, as citizens of a liberal democracy, would likely also be opposed to stable systems like dictatorships or caste systems. Accordingly, they may have viewed the stable systems with some reservations, reflected in lower ratings of the high status group’s warmth. Perhaps warmth would be more purely related to legitimacy in contexts where status stability and instability are equally legitimate states of affairs.

With regard to stereotypes of competence, it is possible that they are relatively indifferent to the stability or legitimacy of status relations. Indeed, previous research shows strong associations between status and competence across a wide range of groups, including experimentally created ones (Cuddy et al., 2008; Oldmeadow & Fiske, 2007), so competence stereotypes may be robust. However, it is important to ensure this was not specific to the experimental context or stimuli used, so should be replicated using a different intergroup context.

In order to replicate these results we conducted a second study, again using a scenario-based design. However, this time we chose a sporting group context involving two football teams that differed in status, and manipulated the legitimacy and stability of the status relation. We felt that legitimacy and stability would be more independent in a sports league context since it is normal and acceptable that in some leagues the lead is occupied by one team for a long time while in others it changes frequently and often. Using a sports league context also allowed us to generalize the results beyond a socio-political context.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Twenty-one male and 111 female (n = 133, one not specified) undergraduate psychology students participated as part of a class exercise. Age ranged from 18 to 39 (median = 19). Ninety-one per cent of the sample had never heard of the football teams described in the vignette, 8.3 per cent had heard of them but knew little about them, and one participant claimed to be quite familiar with the league1.

Materials and Procedure

Participants completed an online questionnaire described as a study of impression formation. After giving informed consent, they read one of four vignettes describing two football teams on the Isles of Scilly—the Woolpack Wanderers and the Garrison Gunners. These are real teams and the only two playing in the Isles of Scilly football league. Information describing the teams and the league was taken from a website, but modified to manipulate the status of the groups, and the legitimacy and stability of the league. Four versions of the vignette were created, varying legitimacy and stability, and participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions by the software.

In each vignette, the Woolpack Wanderers were described as being substantially more successful than the Garrison Gunners at securing corporate sponsorship, which allowed them to buy top quality uniforms and equipment. The Garrison Gunners were described as less successful at securing sponsorship and having just enough money to keep the team going. This was designed to create a status difference between the teams. The final two paragraphs included the manipulations of status stability and legitimacy. In the stable condition, the penultimate paragraph stated: “Part of the Woolpack Wanderer’s success with sponsorship is no doubt due to the fact that they usually win the league. In fact, they have lost to the Gunners only once in the past nine years.” In the unstable condition this paragraph read: “Despite the Woolpack Wanderer’s success with sponsorship, the league is always closely contested. Over the past nine years, the Woolpack Wanderers have won five leagues, and the Garrison Gunners have won four.”

In the legitimate status condition, the final paragraph read: “This year’s trophy went to the Woolpack Wanderers, who won 12 of the 17 matches. Each game was played fair and square, and the referring was faultless. Both teams are taking a short break before training starts again for the new season.” In the illegitimate condition this paragraph read: “This year’s trophy went to the Woolpack Wanderers, who won 12 of the 17 matches. However, there were a number of questionable decisions by the referee during quite a few of the matches, and they all went the way of the Wanderers. It was later discovered that the Woolpack Wanderers had breached the rules of the league by investing in businesses closely associated with the referee. Many believed this was a deliberate attempt to bias the referee and had contributed to the Wanderers winning the league.”

On the next page participants responded to items designed to measure the relative status of the two teams (how prestigious and successful each was) and how competitive each team was (from 1 = not at all, to 7 = extremely). They also rated each team in terms of how likely they were to win the league next year (stability), and indicated to what extent the result of the league was due to biased refereeing (legitimacy).

Finally, participants rated each group in terms of competence and warmth. Four items measured competence (skillfulness, organization, team work, and coordination; alphas > .83) and four measured warmth (friendliness, sociability, trustworthiness, and sincerity; alphas > .83). The order in which participants rated each group was counterbalanced. Rating scales ranged from 1 (‘extremely low’) to 7 (‘extremely high’).

Results

Manipulation checks

The manipulations of status, legitimacy and stability were clearly successful, but there was some variability in perceived status across status systems. A 2 (group) by 2 (stability) by 2 (legitimacy) ANOVA revealed the expected main effect of group, F (1, 129) = 221.34, p < .001, η2 = .63, but additionally a significant group by stability interaction, F (1, 129) = 77.98, p < .001, η2 = .38. This interaction did not qualify the main effect of group, but indicated larger differences in status in the two stable systems (Content and Resentful) than in the two unstable systems (Dynamic and Cynical).

The stability manipulation revealed a main effect of stability only, F (1, 129) = 34.75, p < .001, η2 = .21. The high status group was rated more likely to win next year in the Content (M = 6.00) and Resentful (M = 5.45) systems than in the Dynamic (M = 4.73) and Cynical (M = 4.64) systems. Similarly, the legitimacy item revealed a main effect of the legitimacy manipulation only, F (1, 129) = 141.13, p < .001, η2 = .52. The league was seen as significantly more influenced by biased refereeing in the Cynical (M = 4.84) and Resentful (M = 4.89) systems than in the Content (M = 2.17) and Dynamic (M = 2.30) systems. Overall, our manipulations were successful.

Stereotype patterns across systems

As in Study 1, the group by stereotype dimension interaction was significant with a large effect size in each status system (Fs > 10.78, ps < .003, η2 > .21). The high status group was rated higher in competence and the low status group higher in warmth in each case (see Figure 2). Simple main effects confirmed that the high status group was rated significantly higher in competence than the low status group in all status systems, but more so in the Content, F (1, 29) = 42.25, p < .001, η2 = .59, and Resentful, F (1, 29) = 32.30, p < .001, η2 = .47, systems than in the Dynamic, F (1, 39) = 9.59, p = .004, η2 = .20, and Cynical systems, F (1, 24) = 9.68, p = .004, η2 = .29. The low status group was rated higher in warmth than the high status group in the Cynical, F (1, 24) = 19.00, p < .001, η2 = .44, and Resentful systems, F (1, 37) = 46.07, p < .001, η2 = .56, and less so in the Content, F (1, 29) = 7.20, p = .012, η2 = .20, and Dynamic systems, F (1, 39) = 3.38, p = .078, η2 = .08.

Figure 2.

Competence and warmth ratings of the high status (black bars) and low status (white bars) groups as a function of status stability and legitimacy (Study 2).

To assess whether groups were more differentiated in competence in stable systems and more differentiated in warmth in illegitimate systems we created differentiation scores by subtracting the lower rated group from the higher rated group on each dimension. Consistent with the model, there was a main effect of stability on competence differentiation, F (1, 129) = 10.75, p = .001, η2 = .08, and a main effect of legitimacy on warmth differentiation, F (1, 129) = 30.76, p < .001, η2 = .19. No other main effects or interactions were significant. Groups were differentiated more on competence in stable than unstable status systems, and more differentiated in warmth in illegitimate than legitimate status systems.

General Discussion

This paper represents a first attempt to systematically link stereotype content to the legitimacy and stability of status relations between groups. We reasoned that competence stereotypes would associate with stability and warmth with legitimacy so that groups would be most differentiated in competence when status relations were stable and most differentiated in warmth when status relations were illegitimate. Based on these links we theorised four types of status system, each characterised by a distinct combination of stability and legitimacy and a distinct combination of competence and warmth stereotypes.

Across both studies the manipulations of status stability and legitimacy had significant effects on competence and warmth stereotypes, supporting the view that stereotype contents are indeed related to these variables. The most consistent effect was that groups were more differentiated in warmth when status relations were illegitimate compared to legitimate. While in Study 1 warmth was affected by both stability and legitimacy, in Study 2 warmth was only affected by legitimacy. Stability might have affected warmth in Study 1, using a political intergroup context, if stability and legitimacy were not completely orthogonal, i.e. if participants viewed the stable political systems as less legitimate than the unstable ones. Alternatively, combinations of legitimacy and stability may produce four qualitatively distinct Gestalt-like status systems in which competence and warmth stereotypes do not share simple relationships with stability and legitimacy respectively. In Study 2 a sports league context was used in which legitimacy and stability could be manipulated more independently, and here competence was affected by stability only and warmth by legitimacy only.

The effects of stability and legitimacy on stereotypes of competence and warmth were more clearly separated in Study 2, such that groups were more differentiated in competence in the stable than unstable contexts. However, the perceived difference in status between the groups was also larger in the stable than unstable contexts. Hence it could be argued that the change in competence stereotypes across stable and unstable systems was driven by a concurrent change in status itself, rather than stability per se. This would mean that, holding stability constant, the relationship between status and competence was unchanged across Content, Dynamic, Cynical and Resentful systems. Nevertheless, that the perceived competence of the groups varied across stable and unstable systems supports the importance of this variable in the way groups are differentiated in competence. This hints at a possible social function of competence stereotypes—that they may stabilise status relations.

These effects of legitimacy on warmth stereotypes add further empirical support to the theoretical links between stereotypes and the legitimacy and stability of social inequalities (e.g. Glick & Fiske, 2001; Jost & Banaji, 1994; Tajfel, 1981). Importantly, our data suggest warmth may play a particularly important role in legitimising social inequalities. Previous discussions have tended to focus on stereotypes of competence legitimising status differences by providing moral and intellectual justification them (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Jost & Kay, 2005). While this makes sense, our data suggest it is stereotypes of warmth rather than competence that differentiate legitimate from illegitimate status systems. Stereotypes of warmth, and the emotional and behavioural responses associated with them (Cuddy, et al., 2007), may be more indicative of whether a status system is considered legitimate or not than are stereotypes of competence. If so, warmth stereotypes may play an important role in social change.

The combined effects of stability and legitimacy on competence and warmth stereotypes resulted, in both studies, in groups being least differentiated in Dynamic systems (legitimate, unstable) and most differentiated in Corrupt systems (illegitimate, stable). Interestingly, new cross-cultural data shows that ambivalently stereotyped groups (high on one dimension, low on the other) are more prevalent in countries with high levels of income inequality (Durante, Fiske, Kervyn, & Cuddy, under review). One reason for this pattern could be that social systems within societies characterised by high levels of income inquality are generally seen as less legitimate, though they are often stable. Consequently, in such societies there are likely to be more groups that are seen as competent but lacking warmth (the rich and selfish), or warm but lacking competence (the poor but honest).

Limitations and Directions

A limitation of this research is that it was based on descriptions of groups about which the participants had little or no prior knowledge or involvement. This limits our ability to generalize the findings to contexts where stereotypes are based on experience with groups and on one’s own position in the status hierarchy. Yet many stereotypes are based on sparse second hand information about groups that we have very little knowledge or experience with (Gilovich, 1987; Thompson, Judd, & Park, 2000), and our scenarios would seem an appropriate approximation of these common situations. This approach also has the benefit of maximizing control over the factors that influence participants’ responses, since they can only make judgments on the information given to them. Nevertheless, further research should aim to test the external validity of our model by examining relationships between structural variables and stereotypes in status systems that fit the four types we have identified.

A further avenue for future research is to examine the construction of status-based stereotypes amongst perceiver’s embedded in hierarchical status systems of the sort described here. This would allow better integration of the motivational processes discussed in social identity and system justification theories with stereotype content processes in understanding how groups can achieve social change within the constraints imposed by structural and material inequalities.

Conclusion

We have outlined a model of status systems defined by status stability and legitimacy, and described stereotypes of competence and warmth characterizing high and low status groups within each. Our results suggest that high and low status groups are more sharply differentiated in warmth in illegitimate than legitimate systems, and may also be more differentiated in competence in stable than unstable systems. This, in turn, suggests that stereotypes of competence reflect the social reality, and stereotypes of warmth reflect the perceived morality, of status differences. The power of the stereotype content model comes from its articulation of the ways in which stereotypes are linked to structural relations, and the ways in which these stereotypes shape emotional and behavioural responses to outgroups, in turn affecting structural relations. It outlines how stereotypes both derive from structural realities and give particular meanings to them, portraying them as legitimate and deserved, or illegitimate and in need of change. Stereotypes of warmth play a particularly important role here because they (perhaps more than competence) paint social inequalities with the colours of legitimacy.

Footnotes

Analyses with this participant excluded yielded almost identical results, so they were retained in the analysis.

Contributor Information

Julian A. Oldmeadow, University of York.

Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University

References

- Bettencourt BA, Dorr N, Charlton K, Hume DL. Status differences and in-group bias: A meta-analytic examination of the effects of status stability, status legitimacy, and group permeability. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(4):520–542. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. Competence and warmth as universal trait dimensions of interpersonal and intergroup perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. NY: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Durante F, Fiske ST, Kervyn N, Cuddy AJC. Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12005. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers N. The influence of socio-structural variables on identity management strategies. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European Review of Social Psychology. Vol. 4. Chichester: Wiley; 1993. pp. 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;11(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(6):878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T. Secondhand information and social judgment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1987;23:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST. Ambivalent stereotypes as legitimizing ideologies: Differentiating paternalistic and envious prejudice. In: Jost JT, Major B, editors. The psychology of legitimacy: Emerging perspectives on ideology, justice, and intergroup relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 278–306. [Google Scholar]

- Handley PM. The king never smiles: A biography of Thailand’s Bhumibol Adulyadej. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ, Murray C. The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. NY: Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Banaji MR. The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;33(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Banaji MR, Nosek BA. A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology. 2004;25(6):881–919. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Kay AC. Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotype: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:498–509. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH. Attribution theory in social psychology. In: Levine D, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation. Vol. 15. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1967. pp. 192–241. [Google Scholar]

- Leach C, Snider N, Iyer A. “Spoiling the consciences of the fortunate”: The experience of relative advantage and support for social equality. In: Walker I, Smith HJ, editors. Relative deprivation: specification, development, and integration. NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 136–163. [Google Scholar]

- Oldmeadow JA, Fiske ST. Social status and the pursuit of positive social identity: Systematic domains of intergroup differentiation and discrimination for high- and low-status groups. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2010;13(4):425–444. doi: 10.1177/1368430209355650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway CL, Berger J. The legitimation of power and prestige orders in task groups. In: Webster MJ, Foschi M, editors. Status generalization: New theory and research. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1988. pp. 207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Spears R. Four degrees of stereotype formation: Differentiation by any means necessary. In: McGarty C, Yzerbyt V, Spears R, editors. Stereotypes as explanations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Social stereotypes and social groups. In: Turner JC, Giles H, editors. Intergroup behaviour. Oxford: Blackwell; 1981. pp. 144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MS, Judd CM, Park B. The consequences of communicating social stereotypes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2000;36:567–599. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR, Lind E. A relational model of authority in groups. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 25. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 115–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke B. Morality and competence in person- and self-perception. European Review of Social Psychology. 2005;16:155–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wright SC. Restricted intergroup boundaries: Tokenism, ambiguity, and the tolerance of injustice. In: Jost JT, Major B, editors. The psychology of legitimacy: Emerging perspectives on ideology, justice, and intergroup relations. NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 223–254. [Google Scholar]