Abstract

Alcohol dysregulates the regulation of reproductive vascular adaptations. We herein investigated chronic binge-like alcohol effects on umbilical endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) multi-site phosphorylation and related redox switches under basal (unstimulated) and stimulated (with ATP) states. Alcohol decreased endothelial excitatory Pser1177eNOS (P<0.001), whereas excitatory Pser635eNOS exhibited a main effect of alcohol (↓P=0.016) and ATP (↑P<0.001). Alcohol decreased Pthr495eNOS (P=0.004) levels, whereas inhibitory Pser116eNOS exhibited an alcohol main effect in both basal and stimulated states (↑P=0.005). Total eNOS was reduced by alcohol (P=0.038). In presence of ATP, alcohol inhibited ERK activity (P=0.002), whereas AKT exhibited no alcohol effect. Alcohol main effect on S-nitroso-glutathione reductase (↓P=0.031) and glutathione-S-transferase (↓P=0.027) were noted. Increased protein glutathiolation was noted, whereas no alcohol effect on GSH, GSSG, NOX2 or SOD expression was noted. Thus, alcohol effects on multi-site post-translational modifications and redox switches related to vasodilatory eNOS underscore the necessity for investigating alcohol-induced gestational vascular dysfunction.

Keywords: Endothelium, eNOS, ATP, vascular, FASD

Introduction

Alcohol is a well documented teratogen. Developmental alcohol exposure leads to a range of deficits in the developing fetus including growth restriction, neuroanatomic, behavioral, and cardiovascular deficits collectively termed as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) [1, 2]. Among these deficits, the fetal vascular anamolies have been less investigated. Alcohol administration during pregnancy is reported to decrease placental blood flow in the rats [3] and decrease umbilical blood flow in the sheep [4]. Further, pups born to rats exposed to alcohol during pregnancy exhibit decreased vasorelaxtion [5]. However, the mechanisms underlying these deficits are not well studied.

Nitric oxide (NO), derived from the catalytic activity of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) is an important vasodilator [6]. Many alcohol studies on eNOS have been performed in adult non-pregnant human or animal tissues; for instance, in vitro acute treatment of alcohol (0.1%, 3h) increased bovine aortic endothelial NO [7], whereas alcohol at 4 g/kg for 12 weeks decreased rat aortic eNOS expression, NO levels, and impaired vasorelaxation [8]. Intravenous infusion of alcohol in male and non-pregnant female rabbits [9] as well as in healthy human volunteers [10] dose-dependently decreased levels of exhaled NO. Among studies on fetoplacental cells, in vitro acute alcohol exposure (100 or 200 mM, 2h) decreased placental villi NO and cyclic GMP levels [11]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells, acute alcohol treatment exhibited dose-dependent effects on NO levels [12]. However, none of these studies have investigated effects of a binge-like pattern of alcohol administration or determined the effects of alcohol on eNOS multi-site phosphorylation.

eNOS has four main phosphorylation sites, namely, Pser1179eNOS, Pser635eNOS, Pthr495eNOS, and Pser116eNOS. Out of these sites, Pser1179eNOS and Pser635eNOS are excitatory, whereas Pthr495eNOS and Pser116eNOS are inhibitory [13-15]. An agonist (example, shear stress, ATP, estradiol 17β, etc.) activates the enzyme eNOS via differentially modifying the eNOS multi-site phosphorylation sites [16]. Therefore, we herein for the first time have comprehensively investigated the effects of chronic binge-like alcohol on eNOS multi-site phosphorylation system as well as the related redox balance system under basal (unstimulated) and stimulated (in the presence of the endogenous eNOS activating agonist ATP) states. Our novel findings dilineate alcohol-induced impairment of major post-translational modifications associated with umblical eNOS activity regulation including multi-site phosphorylation, redox switches, and underlying signaling systems.

1. Materials & Methods

2.1 Alcohol Dosing Paradigm

As previously described, we closely mimicked a dose and paradigm of alcohol exposure reported in several animal and human studies [17-20]; in brief, a two week binge-like alcohol exposure paradigm except for two days while passaging (3h/day, 130 mM; human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Lonza) was followed using a sealed compensating system, a pattern of exposure common among women who abuse alcohol during pregnancy [19-25]. This dose mimics clinically relevant abusive patterns of drinking in women of child-bearing age and those who are admitted to emergency wards [17, 26-28]. On the last day of the in vitro experiment, the endothelial cells (primary, 3-4 replicates per treatment group) were serum starved for 4h, treated with or without the endogenous eNOS activating agonist ATP (100 μM, 5 min) [16], scraped and collected in a lysis buffer (Cell Singaling Inc., 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM b-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin) containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, aprotinin, bestatin hydrochloride, N-(trans-epoxysuccinyl)-L-leucine 4-guanidinobutylamide, leupeptin hemisulfate salt, pepstatin A), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma, Na3VO4, sodium molybdate, sodium tartrate, imidazole), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 3 (Sigma, cantharidin, (–)-p-bromolevamisole oxalate, calyculin A).

2.2 Immunoblotting

Solubilized protein was quantified using a modified Lowry assay procedure (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA), and equal volume or mass of protein were separated by size on 4-20% polyacrylamide gels (150 V, 42 min; Mini Protean II, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) alongside Rainbow molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) before transfer to Immobilon P membranes (100 V, 1 h). The Immobilon P membranes were probed using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent detection system, as described by Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Arlington Heights, IL), and exposed to Hyperfilm (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Antibodies to Pser1179eNOS, cav-1, Pser473AKT, total ERK, total AKT, and β-actin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies Inc., total eNOS from BD Transduction laboratories, GP91Phox (NOX2) and all other phosphorylated eNOS antibodies from Millipore Inc. Antisera for Pthr202/tyr204ERK (Promega Inc.), S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR, Lifespan Inc.), glutathione-S-transferase (GST, Pierce Inc.), superoxide dismutase (Abcam Inc.), nitrotyrosine (Sigma), and glutathiolated protein (PSSG, Virogen Inc.) were also utilized for analyses.

2.3 Measurement of glutathione (GSH) and glutathione disulphide (GSSG) using HPLC

Reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) glutathione were extracted from cell lysates containing 50 μg of protein using 1:1 solution of 12 mM iodoacetic acid and 1.5 M perchloric acid to make the final volume to 250 μL and vortexing for 30 seconds. 125 μL of 2M potassium carbonate was added to each tube and vortexed for 30 seconds. Supernatant from the previous step was derivatized to S-carboxymethyl glutathione using 25 mM iodoacetic acid in the presence of 2-mercaptatethanol (for the detection of total glutathione) or 40 mM sodium borate (for the detection of reduced glutathione). Using a modified procedure [29, 30], samples were run separately on HPLC system for the detection of reduced and total glutathione using a Supelco C18 guard column (4.6 mm x 5 cm, 20-40 μm; Supelco® Cat # 59644) and a Supelco C18 column (4.6 mm x 15 cm, 3 μm; Supelco® Cat # 58985). Model 717 plus WISP Autosampler was programmed to mix 25 μl of derivatized sample (or standard) with 25 μl of the o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) reagent for 1 min and then injected the derivatized solution into the HPLC column without any delay. Total run time of 16 min was set at the flow rate of 1.1 ml/min. Initial solvent conditions were 97% A, 3% B run for 1 min. A gradient to 86% A, 14% B was run from 1.1 to 6.5 min. From 6.6 to 9 min, the conditions were maintained at 0% A, 100% B and returned to 97% A, 3% B from 9.1 to 16 min. Mobile phase A was 0.1 M sodium acetate and mobile phase B was HPLC-grade methanol (Fisher Scientific® , Cat # A452-4). 2475 Multi wavelength Fluorescence Detector (Waters® Milford, MA, USA 01757) was set at 220 nm excitation between 0 to 6 min, at 340 nm excitation between 6 to 12 min, and at 220 nm excitation between 12 to 16 min. The setting of excitation at 220 nm before 6 min and after 12 min was designed to suppress fluorescence due to other amino acids that react with OPA. Emission was set at 450 nm between 0 to 16 min and gain of the detection was set at 10. Reduced and total glutathione were quantified on the basis of authentic standards (GSH; Sigma® Cat # G 6529 and GSSG; Sigma® Cat # G 4376) using the Millennium-32 software and workstation.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Interactive effects of alcohol and ATP were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. Further pairwise comparisons were performed when appropriate using Fisher’s protected least significant difference. Level of significance was established at P<0.05. 0.05<P<0.1 were considered trends.

2. Results

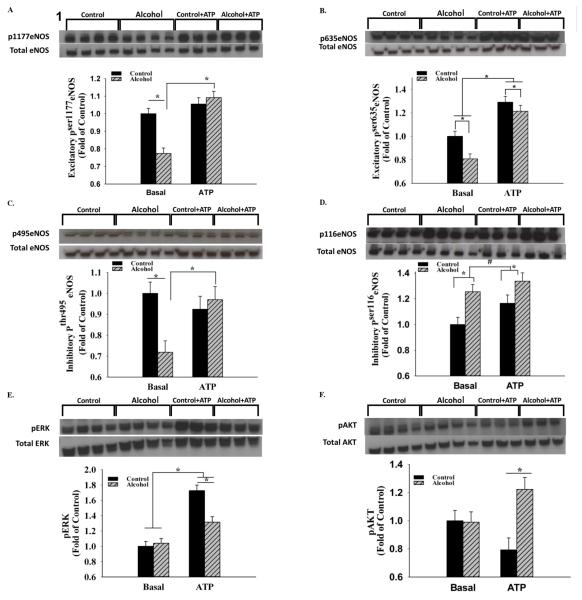

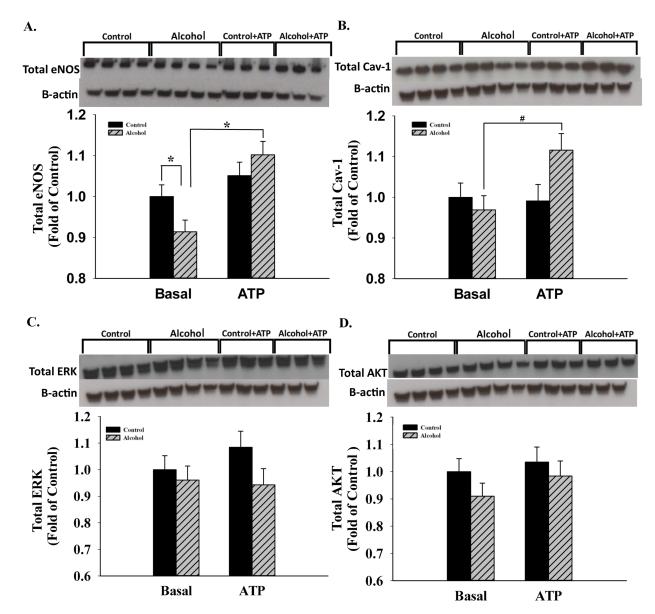

Alcohol significantly decreased umbilical endothelial excitatory Pser1177eNOS by 22.6% (P<0.001), whereas an alcohol effect was not observed in the presence of the agonist ATP (Figure 1). In contrast, the excitatory Pser635eNOS exhibited a significant main effect of both alcohol (↓P = 0.016) and ATP (↑P<0.001). Similar to Pser1177eNOS, the caveolin-1 (cav-1)-binding-associated Pthr495eNOS exhibited a significant interaction; alcohol decreased levels of Pthr495eNOS by 28.1% (P=0.004), whereas an alcohol effect was not observed in the presence of the agonist ATP. In contrast, the inhibitory Pser116eNOS exhibited a main effect of alcohol in both basal and stimulated states (↑P=0.005) and the effect of ATP trended towards significance (P=0.068). The two well studied signaling systems associated with eNOS phosphorylation, namely Pthr202/tyr204ERK and Pser473AKT were studied for underlying mechanisms. ERK activity was not altered in the basal state, whereas in the presence of ATP, alcohol inhibited ERK activity by 23.8% (P=0.002). A significant effect of ATP was further noted independent of alcohol exposure. Activated AKT was not altered by alcohol in the basal state, whereas in the presence of ATP, alcohol significantly increased its levels by 35.1% (P=0.005) showing that alcohol does not alter eNOS multi-site phosphorylation via the classical AKT site. Total eNOS was significantly reduced by alcohol (P=0.038). Furthermore, following chronic alcohol programing, its levels increased stoichiometrically and concomitantly with a trend in cav-1 scaffolding protein levels in response to ATP treatment (Figure 2). However, no changes were noted in the expression of total ERK and AKT. Furthermore, following sucrose density gradient centrifugation of ovine uterine artery endothelial cells, the caveolae enriched fractions were isolated and studied using immunoblotting; excitatory Pser635eNOS was decreased in both the caveolar and non-caveolar and inhibitory Pthr495eNOS was decreased in the caveolar enriched fractions following chronic binge alcohol exposure (Unpublished observations, J. Ramadoss, D.B. Chen, and R. R. Magness). In summary, alcohol interacts with ATP in a complex manner to alter eNOS multi-site phosphorylation status.

Figure 1.

A. In vitro chronic binge alcohol exposure significantly decreased umbilical endothelial excitatory Pser1177eNOS (P<0.001) in the basal but not ATP-stimulated state; B. The excitatory Pser635eNOS exhibited a significant main effect of both alcohol (P = 0.016) and ATP (P<0.001). C. Alcohol decreased levels of Pthr495eNOS (P=0.004) in the basal state, whereas an alcohol effect was not observed in the presence of the agonist ATP; D. The inhibitory Pser116eNOS exhibited a main effect of alcohol in both basal and stimulated states (P=0.005), whereas the ATP effect trended towards significance (P=0.068). E. & F. The two well studied signaling systems Pthr202/tyr204ERK and Pser473AKT associated with eNOS phosphorylation showed absence of effect of alcohol in basal state, whereas alcohol-inhibited ERK activity (P=0.002) and increased AKT activity (P=0.005) in the presence of ATP. *, P<0.05; #, 0.05<P<0.1; 3-4 replicates per treatment group.

Figure 2.

A. & B. Total eNOS was significantly decreased following in vitro chronic binge alcohol exposure (P=0.038), whereas following chronic alcohol programing, its levels increased stoichiometrically and concomitantly with a trend in cav-1 scaffolding protein in response to ATP treatment. C. & D. No changes were noted in the expression of total ERK and AKT. In certain cases, gels were run in replicates and were used for quantification. *, P<0.05. #, 0.05<P<0.1; 3-4 replicates per treatment group.

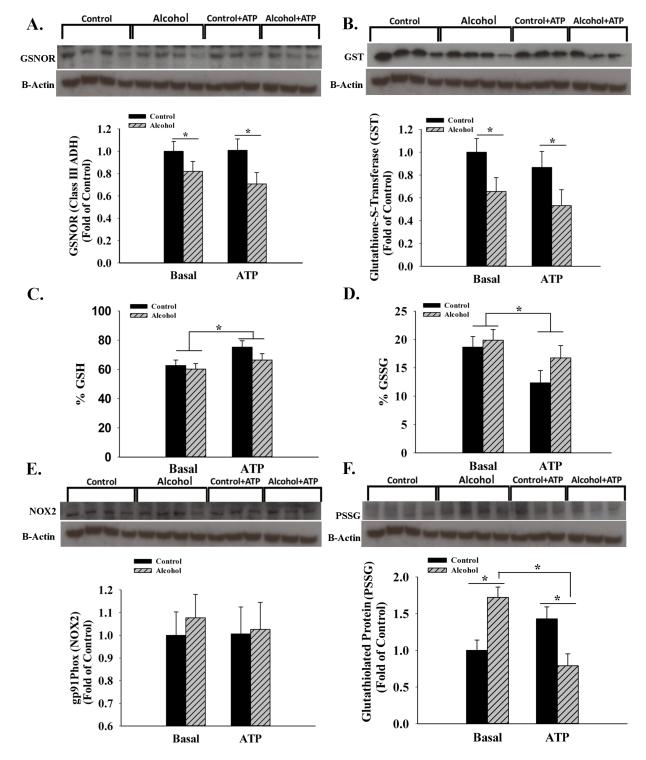

We then investigated GSNOR, an enzyme responsible for denitrosylation of nitrosylated proteins including eNOS (Figure 3). A significant main effect of alcohol (↓P=0.031) was noted independent of ATP showing that alcohol decreases denitrosylation. Further, GST was similarly decreased in the alcohol groups (P=0.027) independent of ATP. In contrast neither GSH nor GSSG were altered by alcohol. We further tested this by measuring NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) responsible for superoxide homeostasis and determined that NOX2 was not altered by alcohol and SOD was barely detectable in any of the treatment groups. Examination of glutathiolated proteins (PSSG) showed bands at ~140 kDa with significantly increased expression in the alcohol group by 72.2% (P=0.005). Similarly, tyrosine-nitratation revealed a band at ~140 kDa and its expression trended lower in the alcohol group (P=0.084, data not shown). In summary, these data show that alcohol produces specialized redox post-translational modifications that are related to the eNOS enzyme system.

Figure 3.

A. & B. Following in vitro chronic binge alcohol exposure, S-nitroso-glutathione reductase (GSNOR, P=0.031) and glutathione transferase (GST, P=0.027) exhibited a significant main effect of alcohol independent of ATP. C. & D. Neither reduced (GSH) nor oxidized (GSSG) glutathione were altered by alcohol. E. & F. NADPH Oxidase 2 (NOX2) was not different among groups. Examination of glutathiolated proteins (PSSG, P=0.005) showed bands at ~140 kDa and was significantly increased following alcohol exposure in the basal state. *, P<0.05; 3-4 replicates per treatment group.

3. Discussion

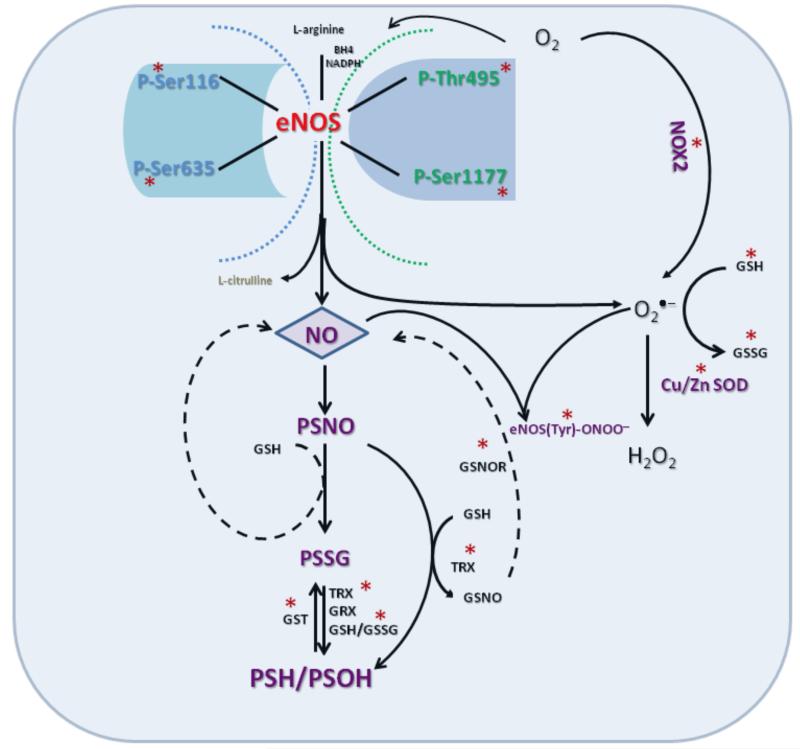

The current report is the first study on the effects of alcohol on umbilical endothelial eNOS post-translational modification and multi-site phosphorylation state. Three major conclusions can be gleaned from this study. First, in vitro binge-like alcohol has detrimental effects on all major eNOS multi-site phosphorylation sites in the primary umbilical endothelial cells (see summary model, Figure 4). Second, there is an interactive effect of alcohol and the endogenous eNOS activating agonist ATP on eNOS multi-site phosphorylation state in these cells. Third, alcohol modulates eNOS-related redox switch post-translational modifications in these cells. These alcohol effects on multi-site post-translational modifications of the major vasodilator system enzyme eNOS has significant implications on fetal umbilical vascular function in FASD.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of chronic binge alcohol-induced dysregulation of the umbilical endothelial eNOS system. The figure depicts the biochemical targets (*, molecules measured) of alcohol. Chronic binge alcohol produces detrimental effects on all major eNOS multi-site phosphorylation sites, and eNOS-related redox switch post-translational modifications. Refer Discussion for details and abbreviations.

In vitro binge alcohol exposure leads to umbilical vascular maladaptations

The current study demonstrates negative effects of alcohol on umbilical endothelial vasodilator system enzyme eNOS and its multi-site post-translational modification. These findings support earlier work showing that umbilical blood flow significantly decreased from 572 + 74 ml/min to 391 + 74 ml/min following intravenous infusion of alcohol in ewes administered with 1g alcohol/min over 1h and the decreases were maintained for 2h post-infusion [4]. Determination of regional blood flow using microspheres in an earlier rodent study that utilized progressively increasing alcohol (10% to 20% V/V before gestation and 30% V/V in utero) doses demonstrated that placental blood flow decreased by ~52% in the alcohol group [3]. Other alcohol studies on the maternal uterine endothelium show similar effects including alcohol-induced decreases in 17β-estradiol induced uterine endothelial cell proliferation, decreases in 20 angiogenesis-associated genes, and impairment of the physiologic conversion of the maternal uterine vasculature within the mesenteric triangle in rats [22, 31, 32]. In summary, alcohol effects on umbilical endothelial eNOS system underscores the necessity for studying alcohol-induced alterations in gestational vascular function and adaptations.

Impact of chronic alcohol on endothelial eNOS-Cav-1 complex

Chronic alcohol decreases the expression of the enzyme eNOS, that catalyzes the production of NO, a major vasodilator. Alcohol programs the endothelial cells such that treatment with eNOS activating agonists like ATP increases the inhibitory cav-1 scaffolding protein expression concomitant with proportional increases in eNOS levels. Interestingly, control endothelial cells were not programmed for altered protein expression upon ATP treatment. Over-expression of cav-1 leads to decreased NO production and cav-1 interaction with eNOS negatively regulates basal NO release [33]. Thus, eNOS and cav-1 are significant targets of chronic alcohol exposure [34-36] in the umbilical vascular endothelial cells.

Interactive effects of alcohol and ATP on eNOS multi-site phosphorylation

Alcohol decreases phosphorylation level of the well known eNOS phosphorylation site Pser1177eNOS in the basal but not ATP-stimulated state. ser1177eNOS is a widely investigated reductase domain excitatory phosphorylation site close to the C-terminus [13] and is shown to be stimulated by mutation of serine to aspartate, and inhibited by mutating the residue to alanine [37]. This site is phosphorylated by bradykinin [38], adiponectin [39], epidermal growth factor [40], histamine [40], thrombin [40], vascular endothelial growth factor [41], and shear stress [42]. ATP is an endogenous vasodilator that binds to endothelial purinergic P2Y receptors and activates eNOS via both signaling cascade(s) activation as well as via an increase in levels of intracellular [Ca2+]i [16]. In this study, we found that in the umbilical endothelial cells, an alcohol effect in the presence of ATP was observed for two of the four phosphorylation sites. Ongoing studies in our lab will block different ATP-stimulated kinases as well as inhibit [Ca2+]i transients to study underlying pathways by which alcohol mediates altered eNOS multi-site phosphorylation under basal and stimulated states. Alcohol also decreased thr495eNOS phosphorylation levels, a site located in the eNOS Ca2+-calmodulin binding domain [43]. thr495eNOS phosphorylation is essential for eNOS-calmodulin interaction and for localizing the enzyme within the caveolar lipid rafts and making it available for extracellular agonists [13, 44]. The decreases in the caveolar Pthr495eNOS levels were confirmed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation showing that although eNOS translocates from the membrane, it is still inactive and probably also inaccessible for further agonist stimulation. Although the most reported signaling molecule for ser1177eNOS phosphorylation is AKT [38], the current report shows that alcohol disrupts its phosphorylation via other mechanisms that may include CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) [45] and AMPK [39] which will be investigated in future. In summary, alcohol-induced reduction of ser1177eNOS phosphorylation might directly result in decreased eNOS enzyme activity because mutation of this residue to aspartate reduces both basal and stimulated NO production [13, 46]. However, alcohol-induced alterations to umbilical endothelial Pthr495eNOS levels may decrease NO production via the effects on subcellular localization of the enzyme within the caveolar lipid rafts [47, 48].

Alcohol further differentially altered the phophorylatyion levels of the two other major sites with significant decreases in the levels of excitatory Pser635eNOS and increases in inhibitory Pser116eNOS in the absence as well as presence of ATP. ser635eNOS is an excitatory site in the CaM autoinhibitory domain [13] and its phosphorylation peaks between 5 and 10 min with sustained levels up to 30 min [44]. NO production from phospho-mimetic (S635D)-expressing cells was significantly higher than that of both control and non-phosphorylatable (S635A) constructs in both basal and increased [Ca2+]i states [49]. The sucrose density gradient centrifugation data further support decreases in excitatory Pser635eNOS in both caveolar and non-caveolar subcellular fractions. Similarly, inhibitory Pser116eNOS is the only site identified in the oxygenase domain of the enzyme [13]. For example, a phosphorylation-deficient mutant of eNOS in which serine 116 was mutated to alanine demonstrated enhanced enzyme activity compared with the wild-type [50]. Furthermore, we did not find that the commonly implicated ERK pathway also related to the eNOS multi-site phosphorylation levels. In summary, alcohol-induced reduction of ser635eNOS phosphorylation might directly result in decreased eNOS enzyme activity because phosphorylation of this site directly relates to sustained endothelial NO production [13, 44]. Further, alcohol-induced increases in Pser116eNOS levels will also contribute to decreased NO production as mimicking dephosphosphorylation of this site via mutation to alanine has been reported to increase the enzyme activity [50].

Impact of chronic alcohol on redox modifications

For the first time, we herein show that alcohol impacts eNOS-related redox post-translational modifications. In the absence or presence of ATP, alcohol decreased the key denitrosylating enzyme GSNOR (also called alcohol dehydrogenase 3). GSNOR regulates both protein (PSNO) and non-protein (GSNO) S-nitrosylation homeostasis [51] and exhibits non-hyperbolic saturation chemical kinetics with ethanol [52] (Figure 4). Further, the observation that alcohol decreased GST expression independent of ATP concomittant with our previous reports that thioredoxin is decreased demonstrate important alcohol effects on protein S-glutathiolation redox post-translational modification and homeostasis of protein thiols (PSH/PSOH) [21, 53-55]. In fact, we confirmed this by probing for PSSG and detected strong bands at ~140 kDa and we reason that eNOS is glutathiolated by alcohol. S-glutathiolation of eNOS results in formation of disulphide bonds between cysteine thiol groups and GSH [56] leading to decreased NOS activity [56, 57]. Furthermore, probing for protein tyrosine nitration yielded bands near 140 kDa showing that alcohol decreased protein nitration. In contrast, alcohol did not affect GSH, GSSG, NOX2, or SOD showing absence of impairment of superoxide homeostasis. Together, we show that alcohol alters eNOS-related specialized redox switches in umbilical endothelial cells.

Perspectives

Prenatal alcohol exposure is a major public health concern as it causes a spectrum of lifelong, debilitating consequences for the affected child. The lack of a clinically relevant viable treatment option for the disorder is likely due to alcohol’s complex mechanisms of action involving multiple organ systems. Although FASD studies so far have primarily focused on the neurodevelopmental sequelae, the current report illustrates major impact of alcohol exposure on the coordination and regulation of umbilical vascular eNOS adaptations. In fact, the current report supports the hypothesis that alcohol fosters a negative synergy by impacting multiple post-translational modifications, and thus impairs the critical eNOS vasodilatory system leading to vascular dysfunction. Thus, a real cure for FASD would likely involve targeting multiple systems including the fetoplacental and umbilical vascular endothelial compartment.

Highlights.

Chronic binge alcohol exposure dysregulates the exquisite coordination and regulation of umbilical endothelial vascular adaptations.

Binge-like alcohol has detrimental effects on all four major eNOS multi-site phosphorylation sites.

There is an interactive effect of alcohol and the endogenous eNOS activating agonist ATP on eNOS multi-site phosphorylation state.

Alcohol modulates eNOS-related redox switch post-translational modifications

Major role for the reproductive vascular system in pathogenesis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Liz Powell (Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Texas Medical Branch-Galveston) for her support in this study.

Source of Funding: NIH AA19446

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, Nordstrom B. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2003;290:2996–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Riley EP, McGee CL. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview with emphasis on changes in brain and behavior. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:357–65. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jones PJ, Leichter J, Lee M. Placental blood flow in rats fed alcohol before and during gestation. Life Sci. 1981;29:1153–9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Falconer J. The effect of maternal ethanol infusion on placental blood flow and fetal glucose metabolism in sheep. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25:413–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Turcotte LA, Aberle NS, Norby FL, Wang GJ, Ren J. Influence of prenatal ethanol exposure on vascular contractile response in rat thoracic aorta. Alcohol. 2002;26:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Toda N, Ayajiki K. Vascular actions of nitric oxide as affected by exposure to alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:347–55. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Venkov CD, Myers PR, Tanner MA, Su M, Vaughan DE. Ethanol increases endothelial nitric oxide production through modulation of nitric oxide synthase expression. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:638–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Washburn SE, Tress U, Lunde ER, Chen WJ, Cudd TA. The role of cortisol in chronic binge alcohol-induced cerebellar injury: Ovine model. Alcohol. 2013;47:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sun MY, Habeck JM, Meyer KM, Koch JM, Ramadoss J, Blohowiak SE, et al. Ovine uterine space restriction alters placental transferrin receptor and fetal iron status during late pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:277–85. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sawant OB, Ramadoss J, Hogan HA, Washburn SE. The Role of Acidemia in Maternal Binge Alcohol-Induced Alterations in Fetal Bone Functional Properties. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acer.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cudd TA, Chen WJ, West JR. Fetal and maternal thyroid hormone responses to ethanol exposure during the third trimester equivalent of gestation in sheep. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kuhlmann CR, Li F, Ludders DW, Schaefer CA, Most AK, Backenkohler U, et al. Dose-dependent activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by ethanol contributes to improved endothelial cell functions. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2004;28:1005–11. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130811.92457.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mount PF, Kemp BE, Power DA. Regulation of endothelial and myocardial NO synthesis by multi-site eNOS phosphorylation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dudzinski DM, Michel T. Life history of eNOS: partners and pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:247–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ramadoss J, Pastore MB, Magness RR. Endothelial Caveolar Subcellular Domain Regulation of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12136. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ramadoss J, Liao WX, Morschauser TJ, Lopez GE, Patankar MS, Chen DB, et al. Endothelial caveolar hub regulation of adenosine triphosphate-induced endothelial nitric oxide synthase subcellular partitioning and domain-specific phosphorylation. Hypertension. 2012;59:1052–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Church MW, Gerkin KP. Hearing disorders in children with fetal alcohol syndrome: findings from case reports. Pediatrics. 1988;82:147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kay HH, Tsoi S, Grindle K, Magness RR. Markers of oxidative stress in placental villi exposed to ethanol. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:118–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gladstone J, Nulman I, Koren G. Reproductive risks of binge drinking during pregnancy. Reprod Toxicol. 1996;10:3–13. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(95)02024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Maier SE, West JR. Drinking patterns and alcohol-related birth defects. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2001;25:168–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ramadoss J, Magness RR. 2-D DIGE uterine endothelial proteomic profile for maternal chronic binge-like alcohol exposure. J Proteomics. 2011;74:2986–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ramadoss J, Magness RR. Multiplexed digital quantification of binge-like alcohol-mediated alterations in maternal uterine angiogenic mRNA transcriptome. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44:622–8. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00009.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].West JR, Parnell SE, Chen WJ, Cudd TA. Alcohol-mediated Purkinje cell loss in the absence of hypoxemia during the third trimester in an ovine model system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1051–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thomas JD, Idrus NM, Monk BR, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates behavioral alterations associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in rats. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2010;88:827–37. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eysseric H, Gonthier B, Soubeyran A, Bessard G, Saxod R, Barret L. Characterization of the production of acetaldehyde by astrocytes in culture after ethanol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1018–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wells DJ, Jr., Barnhill MT., Jr. Unusually high ethanol levels in two emergency medicine patients. J Anal Toxicol. 1996;20:272. doi: 10.1093/jat/20.4.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Urso T, Gavaler JS, Van Thiel DH. Blood ethanol levels in sober alcohol users seen in an emergency room. Life Sci. 1981;28:1053–6. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hammond KB, Rumack BH, Rodgerson DO. Blood ethanol. A report of unusually high levels in a living patient. JAMA. 1973;226:63–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.226.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jones DP, Carlson JL, Samiec PS, Sternberg P, Jr., Mody VC, Jr., Reed RL, et al. Glutathione measurement in human plasma. Evaluation of sample collection, storage and derivatization conditions for analysis of dansyl derivatives by HPLC. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;275:175–84. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang J, Chen L, Li P, Li X, Zhou H, Wang F, et al. Gene expression is altered in piglet small intestine by weaning and dietary glutamine supplementation. J Nutr. 2008;138:1025–32. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gundogan F, Elwood G, Longato L, Tong M, Feijoo A, Carlson RI, et al. Impaired placentation in fetal alcohol syndrome. Placenta. 2008;29:148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ramadoss J, Jobe SO, Magness RR. Alcohol and maternal uterine vascular adaptations during pregnancy-part I: effects of chronic in vitro binge-like alcohol on uterine endothelial nitric oxide system and function. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1686–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Grayson TH, Chadha PS, Bertrand PP, Chen H, Morris MJ, Senadheera S, et al. Increased caveolae density and caveolin-1 expression accompany impaired NO-mediated vasorelaxation in diet-induced obesity. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-1032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ramadoss J, Liao WX, Chen DB, Magness RR. High-throughput caveolar proteomic signature profile for maternal binge alcohol consumption. Alcohol. 2010;44:691–7. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mao H, Diehl AM, Li YX. Sonic hedgehog ligand partners with caveolin-1 for intracellular transport. Lab Invest. 2009;89:290–300. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang X, Abdel-Rahman AA. Effect of chronic ethanol administration on hepatic eNOS activity and its association with caveolin-1 and calmodulin in female rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G579–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00282.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–5. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Harris MB, Ju H, Venema VJ, Liang H, Zou R, Michell BJ, et al. Reciprocal phosphorylation and regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in response to bradykinin stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16587–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chen H, Montagnani M, Funahashi T, Shimomura I, Quon MJ. Adiponectin stimulates production of nitric oxide in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45021–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Thors B, Halldorsson H, Clarke GD, Thorgeirsson G. Inhibition of Akt phosphorylation by thrombin, histamine and lysophosphatidylcholine in endothelial cells. Differential role of protein kinase C. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168:245–53. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dimmeler S, Dernbach E, Zeiher AM. Phosphorylation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase at ser-1177 is required for VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration. FEBS Lett. 2000;477:258–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Boo YC, Sorescu G, Boyd N, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Du J, et al. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3388–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chen ZP, Mitchelhill KI, Michell BJ, Stapleton D, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Witters LA, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of endothelial NO synthase. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:285–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cale JM, Bird IM. Dissociation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and activity in uterine artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1433–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00942.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Dimmeler S, Kemp BE, Busse R. Phosphorylation of Thr(495) regulates Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2001;88:E68–75. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.092677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bauer PM, Fulton D, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, Kemp BE, Jo H, et al. Compensatory phosphorylation and protein-protein interactions revealed by loss of function and gain of function mutants of multiple serine phosphorylation sites in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14841–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ramadoss J, Pastore MB, Magness RR. Endothelial Caveolar Subcellular Domain Regulation of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mineo C, Shaul PW. Regulation of eNOS in caveolae. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;729:51–62. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1222-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Boo YC, Sorescu GP, Bauer PM, Fulton D, Kemp BE, Harrison DG, et al. Endothelial NO synthase phosphorylated at SER635 produces NO without requiring intracellular calcium increase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:729–41. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kou R, Greif D, Michel T. Dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by vascular endothelial growth factor. Implications for the vascular responses to cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29669–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204519200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hou Q, Jiang H, Zhang X, Guo C, Huang B, Wang P, et al. Nitric oxide metabolism controlled by formaldehyde dehydrogenase (fdh, homolog of mammalian GSNOR) plays a crucial role in visual pattern memory in Drosophila. Nitric Oxide. 2011;24:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lee SL, Wang MF, Lee AI, Yin SJ. The metabolic role of human ADH3 functioning as ethanol dehydrogenase. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:143–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Townsend DM, Manevich Y, He L, Hutchens S, Pazoles CJ, Tew KD. Novel role for glutathione S-transferase pi. Regulator of protein S-Glutathionylation following oxidative and nitrosative stress. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:436–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805586200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ramadoss J, Magness RR. Alcohol-Induced Alterations in Maternal Uterine Endothelial Proteome: A Quantitative iTRAQ Mass Spectrometric Approach. Reprodictive Toxicology. 2012;34:538–44. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dalle-Donne I, Colombo G, Gagliano N, Colombo R, Giustarini D, Rossi R, et al. S-glutathiolation in life and death decisions of the cell. Free Radic Res. 2011;45:3–15. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.515217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chen CA, Wang TY, Varadharaj S, Reyes LA, Hemann C, Talukder MA, et al. S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature. 2010;468:1115–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zweier JL, Chen CA, Druhan LJ. S-glutathionylation reshapes our understanding of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and nitric oxide/reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:1769–75. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]