Abstract

Blood-brain barrier (BBB) opening using focused ultrasound (FUS) and microbubbles has been experimentally established as a non-invasive and localized brain drug delivery technique. In this study, the permeability of the opening is assessed in the murine hippocampus after the application of FUS at three different acoustic pressures and microbubble sizes. Using DCE-MRI, the transfer rates were estimated, yielding permeability maps and quantitative Ktrans values for a predefined region of interest. The volume of BBB opening according to the Ktrans maps was proportional to both the pressure and the microbubble diameter. A Ktrans plateau of approximately 0.05 min−1 was reached at higher pressures (0.45 and 0.60 MPa) for the larger-sized bubbles (4–5 and 6–8 µm), which was on the same order as the Ktrans of the epicranial muscle (no barrier). Smaller bubbles (1–2 µm) yielded significantly lower permeability values. A small percentage (7.5%) of mice showed signs of damage under histological examination, but no correlation with permeability was established. The assessment of the BBB permeability properties and their dependence on both the pressure and the microbubble diameter suggests that Ktrans maps may constitute an in vivo tool for the quantification of the efficacy of the FUS-induced BBB opening.

Keywords: permeability, DCE-MRI, focused ultrasound, blood-brain barrier

1. Introduction

The key to the treatment of various neurological diseases resides in the safe opening of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a specialized structure that impedes the delivery of therapeutic agents to the parenchyma (1, 2). Under normal physiological conditions, the BBB blocks molecules that are larger than 400 Da (3) from penetrating the brain parenchyma. Several techniques have been proposed over the years for the opening of the BBB. Hyperosmolar solutions, such as lactamide or mannitol, have been used clinically and experimentally (4, 5) and have been found to increase the permeability of the interendothelial tight junctions. Intracranial operations with a needle have also been performed in patients allowing for a more localized BBB opening (6). More recently, focused ultrasound (FUS) in the presence of circulating microbubbles has been suggested as the only non-invasive, localized and transient method for BBB opening (7, 8).

A series of studies have assessed the extent of the FUS-induced BBB opening and its dependence on various acoustic parameters. With the use of MR (7, 8) and fluorescence imaging (9, 10), the opening has been found to have a significant dependence on the acoustic pressure, the microbubble size distribution (9) and the molecular size of the administered pharmacological compound (10). More specifically, the BBB opening threshold has been found to lie between the peak rarefactional pressures of 0.30 and 0.45 MPa for both the commercial and the custom-made microbubbles that were tested, while a maximum compound size of 2 kDa was found to sufficiently penetrate the brain parenchyma after the FUS procedure. Other studies have focused on the mechanism of the BBB opening by providing detailed descriptions of the different transcapillary molecular pathways that increase the BBB permeability using electron and immunoelectron microscopy (11, 12) or by quantifying the passive acoustic emissions of the FUS procedure (13, 14). Tung et al. (13), in particular, have measured the broadband spectral response acquired with a passive cavitation detector and the findings indicated that inertial cavitation occurs at and beyond the peak rarefactional pressure of approximately 0.45 MPa. Finally, the safety of the technique has been thoroughly investigated using both ex vivo (15, 16) and in vivo (17) methods. For example, Baseri et al. (15) have indicated that the safest acoustic pressure is within the range of 0.3–0.46 MPa based on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) findings.

While all the aforementioned studies have examined the FUS-induced BBB opening from different points of view, to our knowledge no study has emphasized on the in vivo drug kinetics in the sonicated region. Recently, we compared two standardized MR-based pharmacokinetic models, estimating for the first time a numerical permeability value using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) (18). According to the study, the generalized Tofts and Kermode kinetic model (19) yielded reliable transfer rate constants that demonstrated the significant permeability increase in the sonicated hippocampal region compared to the contra-lateral (control) side in mice. Therefore, DCE-MRI could be established as a standardized in vivo evaluation tool for the efficacy of the FUS procedure.

The objective of this paper is to assess the BBB permeability changes when two of the most influential FUS parameters, i.e. the peak rarefactional pressure and the microbubble size distribution, are varied. The general kinetic model (GKM) (19) was used to generate permeability maps and measure the transfer rates in a specific region within the sonicated murine hippocampus at each acoustic pressure and microbubble size. The permeability of the epicranial muscle (no barrier) was also measured and compared with the values derived from the BBB-opened region. T2 imaging and H&E staining were also used to assess the impact of FUS on the neuronal and vascular cells.

2. Methods

2.1. Focused ultrasound setup

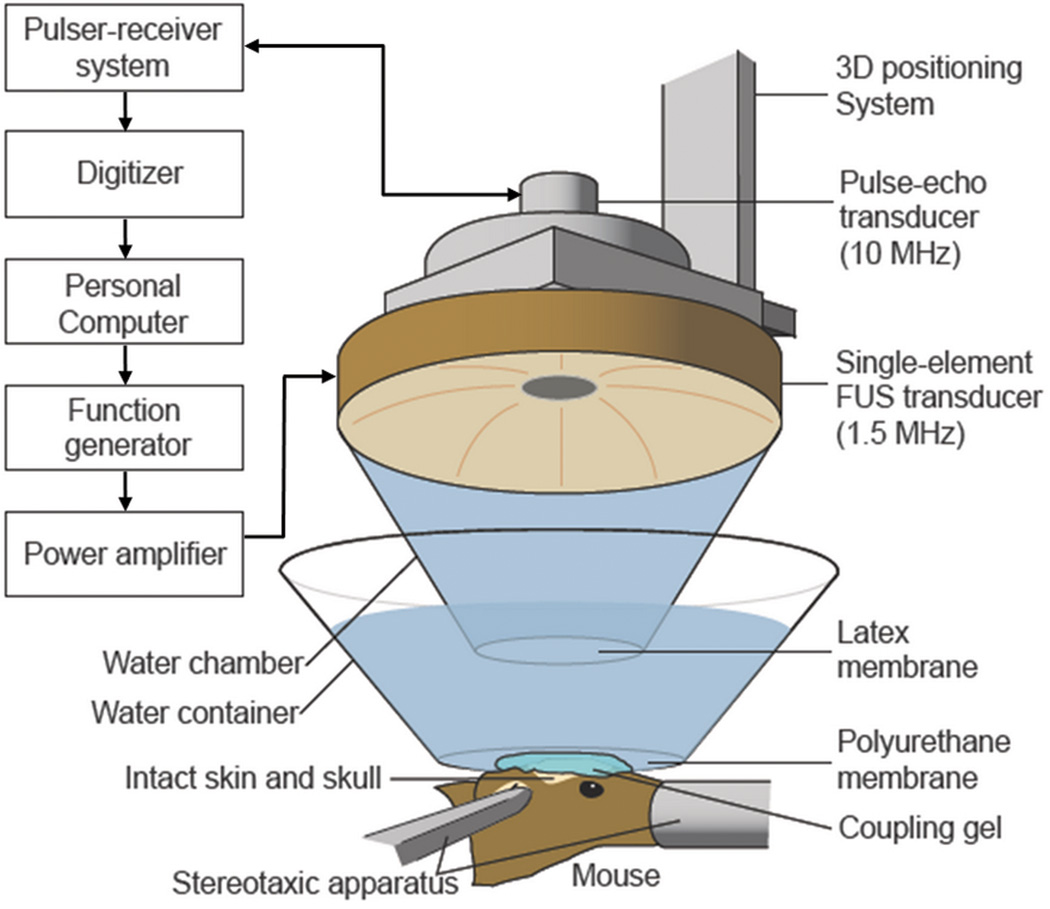

A single-element, spherical-segment FUS transducer (center frequency: 1.525 MHz, focal depth: 90 mm, radius: 30 mm; Riverside Research Institute, New York, USA) was used with a central void (radius: 11.2 mm) that held a pulse-echo diagnostic ultrasound transducer (center frequency: 7.5 MHz, focal length: 60 mm). The transducer assembly was positioned so that the two foci overlapped. A cone filled with degassed and distilled water was mounted onto the transducer system and a fitted polyurethane membrane (Trojan; Church & Dwight Co., Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) supported the water in the cone. The system was attached to a computer-controlled, three-dimensional system (Velmex Inc., Lachine, QC, Canada). The FUS transducer was connected to a matching circuit and was driven by a computer-controlled function generator (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and a 50-dB power RF-amplifier (ENI Inc., Rochester, NY, USA). The pulse-echo transducer was driven by a pulser-receiver system (Panametrics, Waltham, MA) connected to a digitizer (Gage Applied Technologies, Inc., Lachine, QC, Canada) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The FUS experimental set-up.

A needle hydrophone (Precision Acoustics Ltd., Dorchester, Dorset, UK, needle diameter: 0.2 mm) was used to measure the three-dimensional pressure field in a degassed water-tank prior to the in vivo experiments. The calculated peak-negative and peak-positive pressure values were attenuated by 18% to correct for the murine skull attenuation (8), while the lateral and axial full-width-at-half-maximum intensities of the beam were 1 and 7.5 mm, respectively.

2.2. Sonication protocol

All procedures performed were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 40 seven-week old male mice (C57BL/6) of mass 23.87 ± 1.82 g were used for this study. Before the experiment, each mouse was anesthetized using 1–3% isoflurane gas (SurgiVet, Smiths Medical PM, Inc., Wisconsin, USA). Subsequently, the mouse head was shaved and positioned on the stereotactic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) under the transducer assembly during the entire experiment. Coupling gel and degassed water were placed between the skin of the mouse head and the transducer, enabling the focus of the transducer to overlap with the hippocampus and the posterior cerebral artery (PCA). A plastic container and an acoustically and optically transparent surface (Saran, SC Johnson, Racine, WI, USA) maintained the water over the mouse head. The lateral positioning of the transducer was assessed with a grid-positioning method that utilized the pulse-echo diagnostic transducer as described in previous studies (8).

The mice were divided in nine cohorts (Table 1). Each cohort was sonicated using a different combination of microbubble size and acoustic pressure. A minimum of three mice per cohort were used. However, additional mice per cohort were sonicated in most cases, in order to further strengthen the statistical analysis in those cases. The lipid-shelled microbubbles were manufactured in-house by differential centrifugation (20) at mean diameter sizes of 1–2, 4–5 and 6–8 µm. The microbubbles were injected intravenously (IV) through the tail vein at a concentration of approximately 107 numbers/mL, using a 30-G needle. The right hippocampal region of the brain was sonicated immediately after the microbubble injection, using pulsed FUS (burst rate: 10 Hz; burst cycles: 100; duty cycle: 0.067%; frequency: 1.5 MHz) for a duration of 60 s. For each microbubble size, three cohorts of mice were sonicated at three different acoustic pressures (0.30, 0.45, 0.60 MPa peak rarefactional). Previous studies (9) have shown that the safe acoustic pressure for microbubble-mediated BBB opening lies between 0.30–0.45 MPa. However, different sonication parameters (i.e. pulse length and pulse repetition frequency) were used in this study, which can affect the BBB opening properties significantly (21). Thus, a higher acoustic pressure of 0.60 MPa was also included as an input parameter to ensure BBB opening in every case.

Table 1.

Number of sonicated mice (N=40).

| Number of mice |

Acoustic pressure (MPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.60 | ||

| Microbubble size (µm) | 1–2 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| 4–5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | |

| 6–8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

2.3. MRI protocol

All the mice were imaged in a vertical 9.4 T MRI system (DRX400, Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA, USA). Each mouse was scanned 30–40 minutes after sonication, using a 30-mm-diameter birdcage coil. Isoflurane gas (1–2%) was used to anesthetize the mouse at 50–70 breaths/min during the entire MRI procedure. DCE-MRI was performed using a 2D FLASH T1-weighted sequence (spatial resolution: 130×130 µm2; slice thickness 600 µm with no interslice gap; flip angle: 70°, TR/TE=230/2.9 ms, NEX=4, scan time: 88 s). Forty dynamic acquisitions were made over a total period of 60 min. Each acquisition produced 20 horizontal slices that covered the entire mouse head. Upon completion of the second dynamic acquisition, a 0.30 mL non-diluted bolus of gadodiamide (Gd-DTPA) was injected intraperitoneally (IP) through a catheter at a rate of approximately 10 µL/s. The relatively large dosage of contrast agent (CA) was preferred in order to secure the presence of a bolus peak in the vascular system, which is essential for the arterial input function (AIF) determination, but also to have a clearer depiction of the extent of BBB opening (22). IP CA administration was preferred over IV, because it allowed dynamic acquisitions with lower temporal and higher spatial resolution. In addition, several attempts to perform IV catheterization in the tail or femoral vein resulted in clots or scars, which impeded contrast administration (18). Gd-DTPA has been shown to reduce the longitudinal relaxation time when excreted in the extravascular extracellular space (EES), thus enhancing the T1 signal intensity, where the BBB opening has occurred. Upon completion of DCE-MRI, a 2D FLASH T1-weighted sequence (TR/TE=230/3.3 ms; flip angle: 70°; NEX=18; scan time: 9 min 56 s) with higher spatial resolution (matrix size: 256×192; spatial resolution: 86×86 µm2; slice thickness: 500 µm with no interslice gap) and a 2D RARE T2-weighted sequence (TR/TE=3300/43.8 ms; echo train: 8; NEX=10; scan time: 9 min 54 s; matrix size: 256×192; spatial resolution: 86×86 µm2; slice thickness: 500 µm with no interslice gap) were acquired.

2.4. Image processing

The general kinetic model (GKM) was used to measure the BBB permeability in the targeted region. Previous studies (18) have validated the reliability of GKM in the FUS-induced BBB opening. GKM classifies tissues in two compartments, the blood plasma and the EES (23):

| [1] |

where Ktrans, Kep are the transfer rate constants from the blood plasma to the EES and from the EES to the blood plasma, respectively, and Cp, Ct are the concentrations of Gd-DTPA in the blood plasma and the EES, respectively. Cp provides the AIF, which is fitted to a bi-exponential equation:

| [2] |

where Ai, mi (i=1, 2) are the amplitude and decay rates of Cp respectively and t is time. The plasma concentration Cp is calculated as a fraction of the blood concentration Cb, Cp = (1−Hct)Cb, where Hct=0.45 is the hematocrit level for wild-type mice. The difficulty in obtaining an accurate AIF from a detectable vessel in the dynamic images has been reported and assessed with various estimating models (24). However, recent studies (24) have demonstrated that selecting a population average from a large group of the same strain of animals to determine the AIF can be both accurate and robust. In this study, the entire cohort of mice was used to determine the AIF, by averaging the Gd-DTPA concentration changes in the internal carotid artery (ICA), as shown in previous studies (18).

Signal intensity in T1 images is translated to tracer concentration, using the Solomon-Bloembergen equation (25). The equation assumes a linear relationship between the concentration of the CA ([Gd]) and the relaxation rate difference (ΔR1). Relating the relaxation rate to signal intensity (S) in the gradient echo MR images yields a linear relationship between S and [Gd]:

| [5] |

where T1,pre is the longitudinal relaxation time of the corresponding tissue before the CA administration, r1 is the longitudinal relaxivity of the CA and Spre, Spost are the signal intensities before and after Gd-DTPA injection, respectively. Phantom experiments in the 9.4 T MRI system have shown that the r1 relaxivity of gadodiamide (Omniscan®, molecular weight of 530 Da) is approximately 2.6 mM−1s−1, while the longitudinal relaxation times of brain tissue (0.9 s) and arterial blood (1.5 s) in mice have been reported in previous studies, using arterial spin labeling techniques (26).

Prior to the quantitative Ktrans measurements, all the images were smoothed using a 3-by-3 averaging linear filter from the Image Processing Toolbox® of Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). In addition, since the actual Gd-DTPA injection time occurred approximately 3 min after the beginning of DCE-MRI, exclusion criteria were set for the estimated Gd-DTPA injection time (t<0 or t>30 min) to avoid any fitting divergences. The 30-min threshold was selected in accordance with the AIF curve, which showed that Gd-DTPA uptake in the intravascular space reached a “steady-state” approximately 30 min after the beginning of the dynamic acquisition (Fig. 2). Thus, it was assumed that any CA uptake by the tissue after 30 min is the result of diffusion. The spatial permeability distribution was estimated by counting the voxels that exhibited a Ktrans value over a predefined threshold (0.005 min−1). The threshold was selected in the mouse that showed the smallest BBB opening, using the quantification method described below. The estimations represented the volume area in the sonicated region where there was a clear permeability increase. The Ktrans values were measured both pixel-by-pixel, generating transverse and reconstructed coronal permeability maps of the mouse brain, and for a circular region of interest (ROI) of 1 mm in diameter in the targeted hippocampal area and the control side. The ROI was applied on the slice with the highest T1 signal enhancement due to BBB opening and the ROI size was selected so it matched the axial full-width-at-half-maximum intensity area dimension of the beam. If the temporal Gd-DTPA concentration profile of a pixel fitted the AIF curve (Fig. 2), then that pixel was excluded and the remaining pixels within the ROI were averaged to extract the Ktrans value. The permeability was also estimated in the epicranial muscle (Fig. 3g), where the vessels lack a protective barrier, to compare the Ktrans value of muscle tissue (no barrier) with the one in the BBB-opened region. More specifically, a circular ROI with similar dimensions to the one described above was applied on the anterior left epicranial muscle on the transverse MR images, away from the sonicated region and Ktrans was averaged over the entire mouse cohort (N=40).

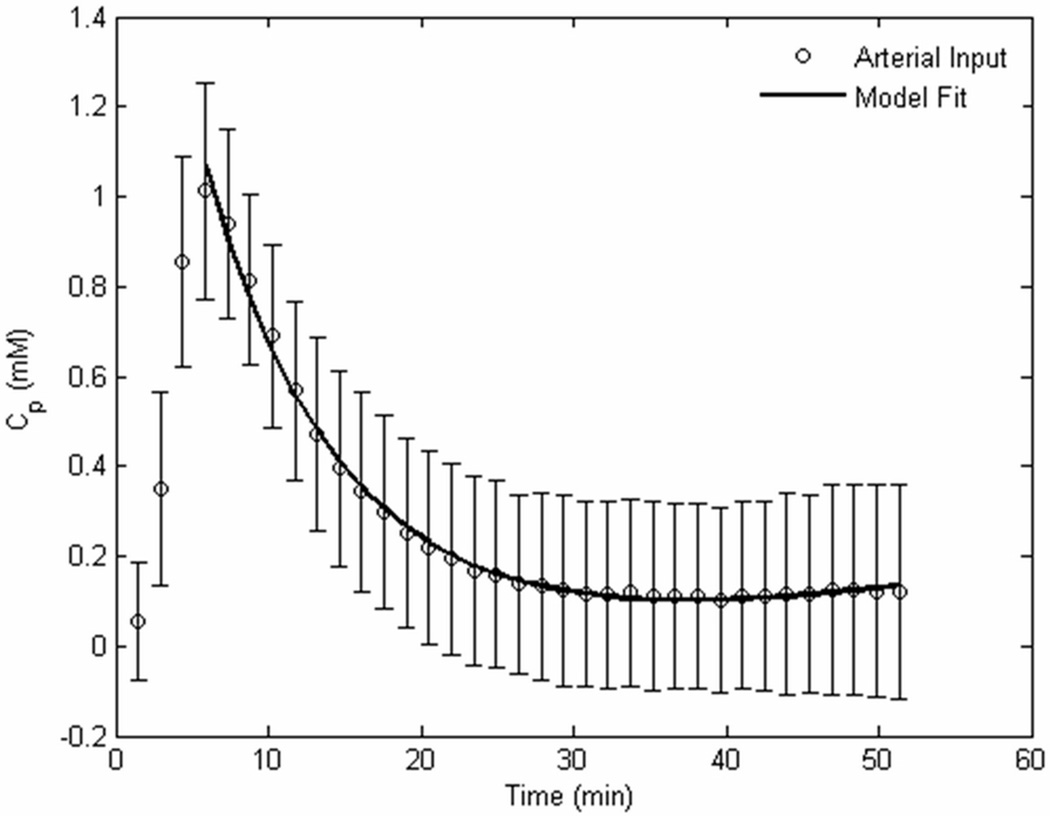

Fig. 2.

The arterial input function, averaged from a population of all 40 mice, by measuring the Gd-DTPA concentration in the internal carotid artery on the dynamic images.

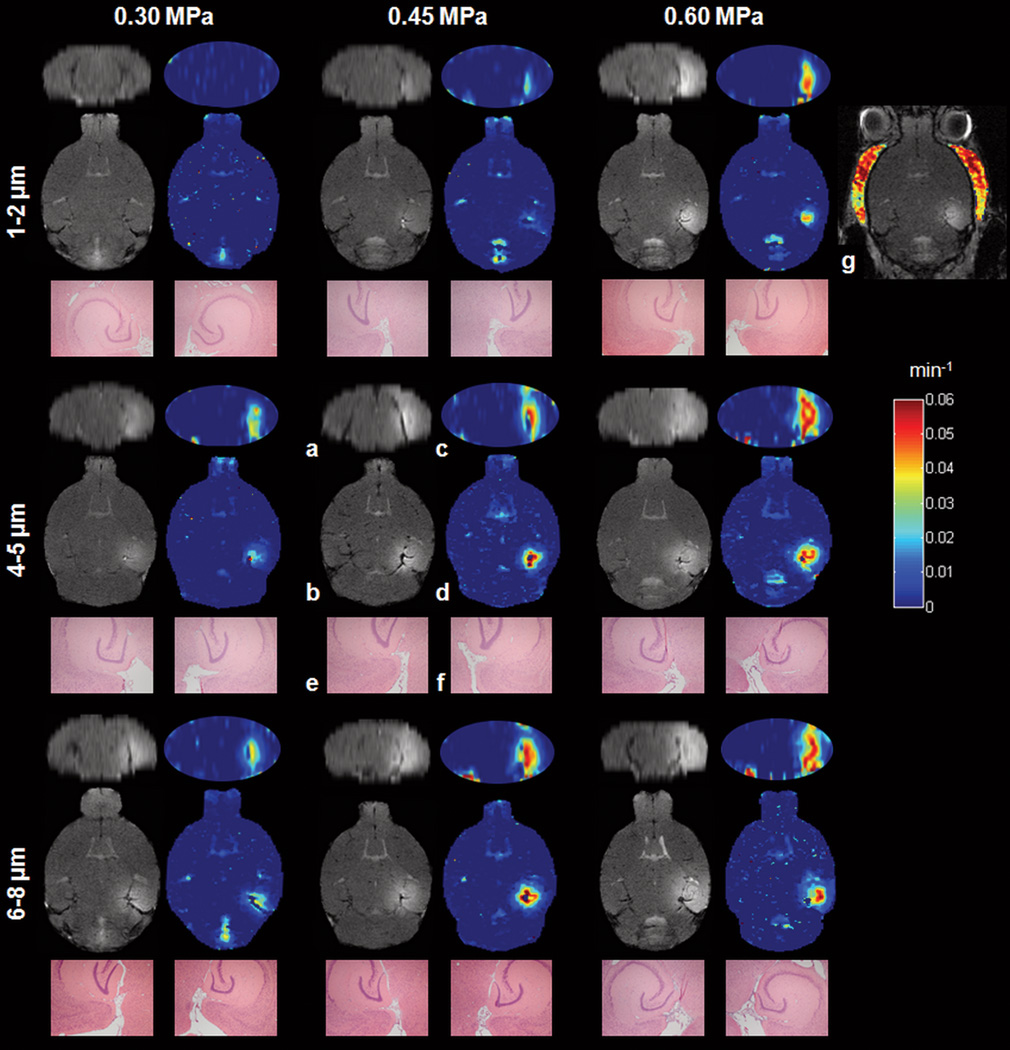

Fig. 3.

(a) Reconstructed coronal and (b) transverse T1 images, (c, d) corresponding permeability maps and H&E sections (40× magnification) of the (e) control and (f) sonicated area of the hippocampal region. The nine different image sets represent nine typical cases from each mouse cohort. The center indicated on each H&E image was manually aligned with the highest contrast-enhanced region on the MR and permeability images shown in (b) and (d), respectively. No damage was detected in any of these cases (see Fig. 5 for cases with damage). (g) The permeability map of the epicranial muscle of the 0.60 MPa/1–2 µm mouse case is presented for comparison. (a, b) T1 images were acquired immediately after the (c, d) DCE-MRI acquisition, 1.5 h after sonication.

The general kinetic algorithm determined both the Ktrans and Kep values, but this study emphasized only on Ktrans, which represents the Gd-DTPA leakage from the systemic circulation and is mostly influenced by the concentration changes immediately after the Gd-DTPA injection. Kep values are mostly influenced by the “steady-state” time points of the concentration curves (Fig. 2), when equilibrium is reached between the EES and the blood plasma concentrations (27, 28).

2.5. Physiological assessment

The mice were sacrificed seven days after sonication and prepared for histology to assess the long-term bioeffects of FUS and separate reversible from irreversible damage. In addition, a parallel study was conducted by our group, which assessed these effects three hours after sonication, which is currently under review elsewhere. A mixture of oxygen (0.8 L/min at 1.0 Bar, 21°C) and 1.5–2.0% vaporized isoflurane (Aerrane, Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) was used to anesthetize the mice and their subsequent transcardial perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (5 min) and 4% paraformaldehyde (8 min) at a flow rate of 6.8 mL/min. After soaking the head in paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, the skull was removed and the brain was fixed again in 4% paraformaldehyde for 144 hours. The brain was embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned into 6 µm thick transverse sections, and then stained with Haematoxylin and Eoisin (H&E). The evaluator searched for dead neurons and erythrocyte extravasations around the sonicated region using microscopy and was blinded with respect to the pressure amplitude and microbubble size. The contrast-enhanced MR images were used as a guide for the determination of the sonicated area. The microscopic examination was also performed on the left hippocampal area, which was used as a control.

The post-contrast T2 images were used as complementary information for the assessment of any physiological changes in the targeted region approximately 2 h after sonication. No quantification was performed in the T2 images, since the field inhomogeneities that the susceptibility effects generate render such quantifications nonreproducible (29).

3. Results

The population-averaged AIF of the IP-injected CA in the blood stream showed a significantly slower Gd-DTPA uptake compared to previously reported IV-administered AIFs (30), where a bolus peak is detected only seconds after the injection. Fig. 2 shows that the bolus peak occurred 5–6 min after the IP injection. The Gd-DTPA concentration decayed exponentially for approximately 25 min after the bolus peak and reached a steady-state concentration onwards. The slow Gd-DTPA uptake, associated with the IP administration, allowed the acquisition of lower temporal resolution dynamic images with relatively increased spatial resolution. The bi-exponential fitting of the AIF yielded the amplitude and decay rates (A1, m1, A2, m2) = (0.02, −0.06, 1.24, 0.17), which were subsequently used for the EES concentration fits.

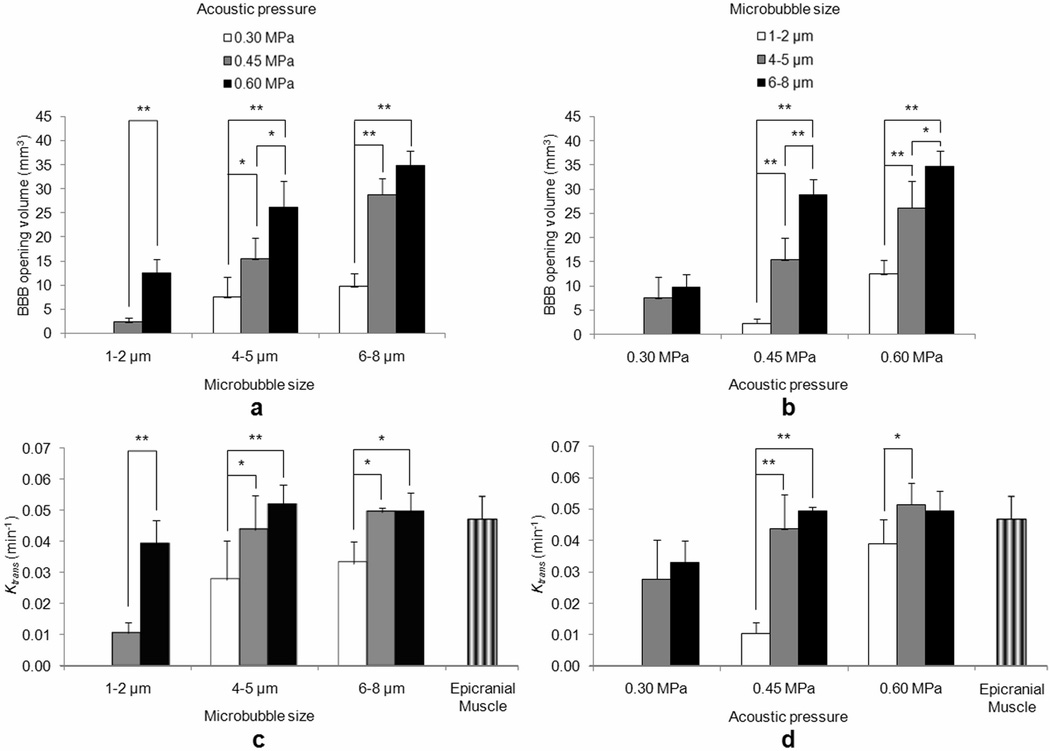

The permeability maps (Fig. 3) assessed both the efficacy of the targeting and the spatial extent of the opening. The 1–2 µm bubbles exhibited no uptake of Gd-DTPA at 0.30 MPa and a small uptake at 0.45 MPa, which covered a volume of 2.3 ± 1 mm3. At 0.60 MPa, a larger area of 12.5 ± 2.8 mm3 exhibited a Ktrans higher than 0.005 min−1. Similar Ktrans distributions were found between the 4–5 µm/0.30 MPa and 6–8 µm/0.30 MPa cases (7.5 ± 4.2 and 9.7 ± 2.7 mm3, respectively), resulting in mildly permeable BBB openings (Fig. 4a). Higher BBB opening volumes were measured in the cases of 4–5 µm/0.45 MPa, 6–8 µm/0.45 MPa, 4–5 µm/0.60 MPa, and 6–8 µm/0.60 MPa (15.4 ± 4.4, 28.8 ± 3.3, 26.1 ± 5.7 and 34.8 ± 3.1 mm3, respectively) (Table 2). The statistically significant p-values for each acoustic pressure and microbubble size using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variances are depicted on the corresponding graphs (Fig. 4a and b, respectively). A linear increase of the BBB opening volume with pressure (R2=0.987) and bubble diameter (R2=0.995) was found. The linearity was mostly evident for the higher pressures (0.45, 0.60 MPa) and larger bubble diameters (4–5, 6–8 µm) (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

Mean (a, b) volumetric and (c, d) quantitative Ktrans measurements. The results are presented in two different ways to demonstrate the dependence of the BBB opening volume and Ktrans on both the (a, c) acoustic pressure and the (b, d) microbubble size. The (c, d) mean Ktrans in the epicranial muscle (no barrier) is also presented for comparison. One asterisk (*) refers to a statistical significance of P<0.05 and two asterisks (**) refer to a statistical significance of P<0.01.

Table 2.

Volumetric and quantitative Ktrans measurements.

| Microbubble size (µm) |

Acoustic pressure (MPa) | ||

| 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.60 | |

| Volumetric measurements (mm3) | |||

| 1–2 | - | 2.314 ± 0.964 | 12.51 ± 2.828 |

| 4–5 | 7.543 ± 4.244 | 15.416 ± 4.441 | 26.106 ± 5.568 |

| 6–8 | 9.729 ± 2.725 | 28.778 ± 3.332 | 34.764 ± 3.13 |

| Quantitative measurements (min−1) | |||

| 1–2 | - | 0.0105 ± 0.0035 | 0.039 ± 0.0078 |

| 4–5 | 0.0277 ± 0.0125 | 0.0437 ± 0.011 | 0.0515 ± 0.0068 |

| 6–8 | 0.0329 ± 0.0071 | 0.0494 ± 0.0014 | 0.0493 ± 0.0063 |

The quantitative measurements provided numerical permeability values of the BBB opening (Fig. 4b). The opening threshold for the 1–2 µm bubbles was 0.45 MPa, yielding a Ktrans value of 0.011 ± 0.004 min−1, while at 0.60 MPa Ktrans reached a value of 0.039 ± 0.008 min−1. The 4–5 µm bubbles exhibited higher Ktrans values, i.e. 0.028 ± 0.013 min−1, 0.044 ± 0.011 min−1 and 0.052 ± 0.007 min−1, for the pressures of 0.30, 0.45 and 0.60 MPa, respectively. Similar results with the 4–5 µm bubbles were found for the 6–8 µm, where the estimated Ktrans was 0.033 ± 0.007 min−1, 0.049 ± 0.001 min−1 and 0.049 ± 0.006 min−1 for the pressures of 0.30, 0.45 and 0.60 MPa, respectively (Table 2). The statistically significant p-values for each acoustic pressure and microbubble size using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variances are depicted on the corresponding graphs (Fig. 4c and d, respectively). The permeability of the epicranial muscle (Fig. 3g) was also measured in every mouse and the mean Ktrans value throughout the entire group of mice was equal to 0.047 ± 0.007 min−1 (Fig 4c, d).

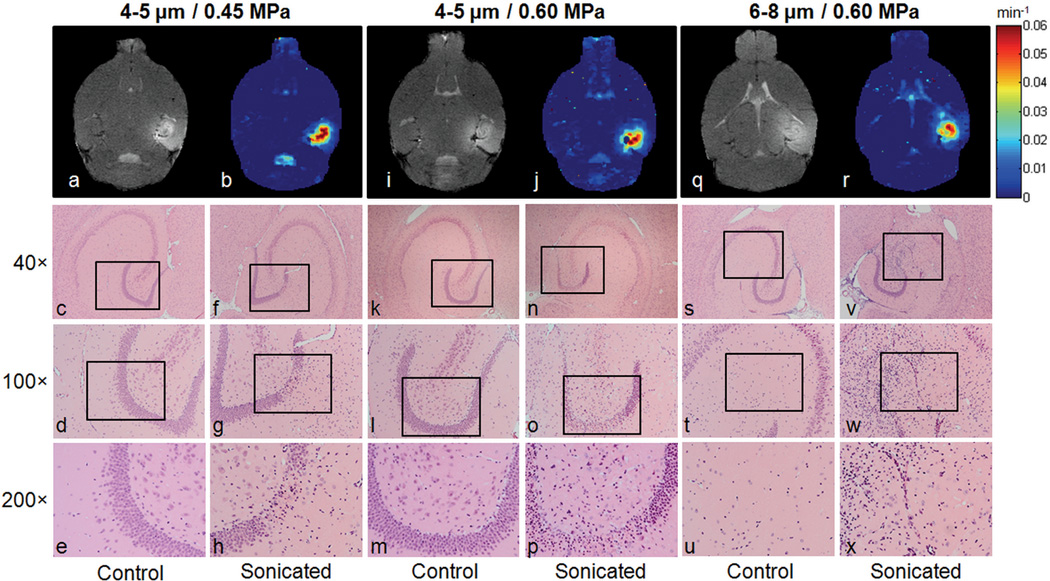

The histological findings showed that only three out of all mice used in this study revealed some structural neuronal damage and cell loss in the sonicated hippocampal area. In two of these mice, which were sonicated at 0.45 and 0.60 MPa, using 4–5 µm microbubbles (Fig. 5c–h and k–p, respectively), cell loss was detected in the granule cell layer of the right dentate gyrus (GrDG). Moreover, the presence of dark neurons in the layer could be an indication of apoptosis. More serious damage was found in the 6–8 µm/0.60 MPa case (Fig. 5s–x), which underwent a major deformation of the structure of the CA3 field of the right hippocampus, followed by cell loss and multiple dark neurons. However, the H&E slices of all the mice showed no red blood cell extravasations that could indicate hemorrhage. The T1 images (Fig. 5a, i, q) and the permeability maps (Fig. 5b, j, r) of the corresponding mice, acquired approximately 1.5 h after sonication are presented along with the histological findings, but no direct correlation could be found between the two imaging techniques.

Fig. 5.

Permeability and histological findings of the only three mice that exhibited neuronal damage and cell loss. (a) T1 image, (b) corresponding permeability map and (c–h) H&E sections of the first mouse, sonicated at 0.45 MPa using 4–5 µm bubbles. (i) T1 image, (j) corresponding permeability map and (k–p) H&E sections of the second mouse, sonicated at 0.60 MPa using 4–5 µm bubbles. (q) T1 image, (r) corresponding permeability map and (s–x) H&E sections of the third mouse, sonicated at 0.60 MPa using 6–8 µm bubbles. The black boxes in (c, f, k, n, s, v) refer to the regions of interest depicted in (d, g, l, o, t, w), respectively. The black boxes in (d, g, l, o, t, w) refer to the regions of interest depicted in (e, h, m, p, u, x), respectively.

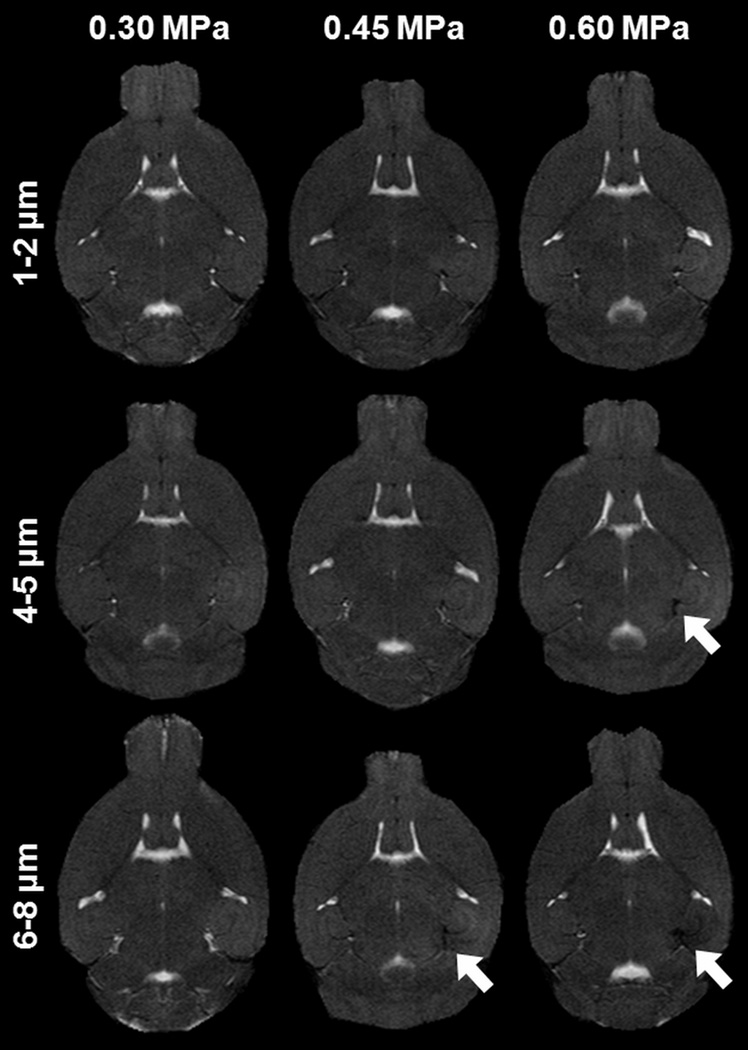

T2 imaging was used as a complementary tool for the assessment of any physiological changes in the sonicated region. Dark regions were detected in the sonicated region in most of the cases of higher pressures and larger microbubbles (Fig. 6), but a distinct correlation with the histological findings could not be established, since H&E staining showed no signs of erythrocyte extravasations. This led to the conclusion that the dark regions in T2 imaging were the result of susceptibility artifacts from the excessive Gd-DTPA excreted in the EES, rather caused by hemorrhage.

Fig. 6.

Transverse T2 images of the brain from each mouse cohort. Dark areas in the sonicated regions (indicated by white arrows) were detected at higher pressures for the larger bubbles as a result of susceptibility artifacts from the excessive Gd-DTPA presence in the extravascular extracellular space.

4. Discussion

In this study, the permeability properties of the FUS-induced BBB opening at different microbubble sizes and acoustic pressures were mapped and quantified. We used GKM to measure the Ktrans values in 40 mice, which were sonicated at three peak rarefactional acoustic pressures (0.30, 0.45 and 0.60 MPa), using three different microbubble sizes of 1–2, 4–5 and 6–8 µm in diameter. Transverse and coronal permeability maps were generated, which exhibited the extent of the Gd-DTPA uptake in the right hippocampal area and its proximity. Quantitative measurements of Ktrans were also carried out, providing a numerical evaluation of the efficacy of the FUS-induced BBB opening. H&E staining was performed in all mice seven days after sonication, to assess any structural macroscopic damage. Our findings showed that the volume of the opening is directly proportional to both the acoustic pressure and the microbubble size for the larger bubbles. The volume spanned from 4.1 to 31.1 mm3 for the 4–5 µm bubbles and from 6.8 to 37.7 mm3 for the 6–8 µm bubbles (Fig. 4a). The 1–2 µm bubbles yielded a mean volume of 8.4 ± 3.7 mm3 (0.45 and 0.60 MPa together) (Fig. 4b). The quantitative permeability measurements demonstrated that the pressure of 0.30 MPa with 4–5 and 6–8 µm bubbles yielded a subtle BBB opening with a mean Ktrans of 0.03 ± 0.011 min−1 (Fig. 4d). For the same bubble sizes, a Ktrans plateau (0.048 ± 0.008 min−1) was reached at higher acoustic pressures (Fig. 4d). The plateau was in excellent agreement with the Ktrans that was found in the epicranial muscle (0.047 ± 0.007 min−1) (Fig. 3g), implying that at higher pressures and for larger bubbles the permeability properties of the sonicated hippocampal vessels are similar to the properties of the vessels that do not possess a barrier. On the other hand, relatively smaller BBB openings were detected with the 1–2 µm bubbles (Fig. 4c), where the pressure of 0.45 MPa was the BBB opening threshold, giving a mean Ktrans of 0.011 ± 0.004 min−1. At 0.60 MPa, a clear opening was observed with a mean Ktrans of 0.039 ± 0.008 min−1.

The 4–5 and 6–8 µm microbubbles appeared to have similar permeability values for each acoustic pressure that was used, although the BBB opening volume measurements exhibited a linear increase. This could be explained by the oscillatory behavior of the bubbles within the sonicated vessel. The wall boundaries of the capillaries, which span from 6 to 10 µm in diameter in the hippocampal region of the mouse brain, could be an important limiting factor in the oscillatory expansion of the bubbles during sonication. Hence, both the 4–5 and 6–8 µm bubbles are expected to expand up to the same threshold within a compliant vessel, leading to similar transfer constants. Relatively lower Ktrans values were reported in the case of 1–2 µm bubbles. These bubbles have a smaller contacting area with the vessel wall and thus, may induce smaller regions with BBB opening. Also, although the number distribution for the 1–2 µm bubbles was consistent before and after the experiments, the bubble volume distribution was shifted to higher microbubble diameter sizes, sometimes within less than 8 h after their manufacturing. However, the consistency of the volumetric and Ktrans measurements across different mice and the significant difference that was observed between the small and the larger-sized bubbles verify the reliability of our permeability findings. In the future, monodispersed microbubbles with more stable shells, i.e. at higher molecular weights, will be used.

The reliability and the limitations of DCE-MRI and GKM for the permeability assessment of the FUS-induced BBB opening have been addressed in a previous study (18), which estimated the Ktrans and Kep values and the Gd-DTPA concentration fits for both GKM and the reference region model (31). The IP CA administration, the time-dependence of Ktrans and the CA diffusion within the EES are the most important potential sources of error. The IP Gd-DTPA injection provides an alternative method of estimating the transfer rate constants without the requirement for a temporal resolution of unit seconds. However, DCE-MRI studies with IV Gd-DTPA injections need to be carried out to compare the estimating constants with those of other BBB permeability models, such as tumors (32), injuries (33) or osmotic BBB disruptive models (34). Also, Ktrans is expected to decrease over time, as BBB properties will change. A strict timeline needs to be followed during the FUS and the DCE-MR acquisitions, to be able to extract solid conclusions from the permeability results. Finally, inaccurate Ktrans values may result from the GKM, since it does not account for the Gd-DTPA diffusion in the EES. Several studies have demonstrated that incorporating a CA diffusion (28), or transcytolemmal water exchange (35) coefficient, in the kinetic model can significantly increase the accuracy of the permeability measurements, especially in BBB disruptive models (34). Future studies will include periodic Ktrans measurements while the BBB remains open, which will allow us to better understand the closing mechanism of the barrier. Finally, additional parameters that permit to evaluate the efficacy of the BBB opening, such as the maximum uptake and washout slope, the Gd-DTPA diffusion in the EES and the EES volume fraction (ve) will be added in our future model estimations, which will provide additional information on the pharmacokinetics.

The histological findings of this study revealed that no significant damage was induced in most of the sonicated mice, demonstrating that the permeability can increase, but not at the expense of safety. Three out of forty mice (7.5%) showed signs of neuronal damage or cell loss in the sonicated hippocampus seven days after sonication at pressures higher than 0.45 MPa and microbubble sizes larger than 4–5 µm (Fig. 5). The damage was represented by the presence of necrotic or apoptotic cells. In one particular case, a significant deformation of the right hippocampal anatomical structure was observed. Overall, the acoustic pressure of 0.30 MPa for larger bubbles and the pressures of 0.45 and 0.60 MPa for the 1–2 µm bubbles appeared to always induce safe BBB opening, according to the 7-day H&E findings. These findings indicate that larger bubbles and the 1–2 µm bubbles may induce larger and smaller BBB openings, respectively, than the commercial microbubbles that have been used in other studies (15).

The presence of dark regions in T2 imaging (Fig. 6) at higher FUS pressures using larger-sized bubbles was found not to correlate with hemorrhage, since no red blood cell extravasations were found at H&E examination of any of the mice used in this study. Thus, the dark regions were assumed to be directly related to field inhomogeneities, because of the excessive Gd-DTPA presence in the EES. Liu et al. (17) have suggested that susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) can detect massive hemorrhagic regions after FUS at the acoustic pressure of 3.47 MPa, but more subtle effects on the brain, as was the case at the low acoustic pressures studied in this paper, appear to be a challenge on the sensitivity and spatial resolution of the MRI used. Future studies will entail histological assessment of the mouse brains on the day of sonication with additional histological examination, which will allow us to accurately detect and characterize other type of damage that has been induced and subsequently relate it to the measured permeability increase.

5. Conclusions

This study has investigated the relationship between permeability, the diameter of the administered microbubbles and the peak rarefactional pressure of the FUS-induced BBB opening. Nine different groups of mice were sonicated using three microbubble sizes (1–2, 4–5 and 6–8 µm) and three acoustic pressures (0.30, 0.45 and 0.60 MPa). The volumetric and quantitative permeability measurements showed that Ktrans in the sonicated region is increasing with the bubble size and the acoustic pressure. The volumetric area of the BBB opening spanned from 1.5 to 37.7 mm3, showing a linear increase with the bubble sizes for the higher acoustic pressures (R2≥0.98). With the exception of the 1–2 µm bubbles, the acoustic pressure of 0.30 MPa yielded a mean Ktrans of 0.03 min−1, while a plateau was reached over 0.45 MPa at approximately 0.05 min–1. An excellent agreement was found between the Ktrans plateau and the permeability value of the epicranial muscle, i.e., at the absence of a barrier. The 1–2 µm bubbles did not open the BBB at 0.30 MPa, while at 0.45 and 0.60 MPa they yielded mean Ktrans values of approximately 0.01 and 0.04 min−1, respectively. Histological examination of H&E sections revealed some structural damage in 7.5% of the mice and only at higher pressures and larger bubbles, but unlike in previous reports no hemorrhagic regions were detected, including in the cases of the highest acoustic pressure studied (0.60 MPa) and the largest bubbles (6–8 µm). This points to the effect of the shorter pulse length used here. The results indicate that DCE-MRI could be used as a diagnostic method for the assessment of the permeability of the barrier and thereby efficacy of drug delivery through the FUS-induced BBB opening.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored in part by NIH (EB009041) and NSF CAREER (0644713). The authors wish to thank Jameel Feshitan, MS and Mark Borden, PhD for the manufacturing of the microbubbles and Kirsten Selert, BS Anna Wang, BS and Gesthimani Samiotaki, MS for the histological specimen preparation and analysis.

References

- 1.Abbott NJ, Rönnbäck L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortin D. Altering the properties of the blood-brain barrier: Disruption and permeabilization. Prog Drug Res. 2003;61:125–154. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8049-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapoport SI. Osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier: Principles, mechanism, and therapeutic applications. J. Cell. Mol. Neurob. 2000;20:217–230. doi: 10.1023/A:1007049806660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doolittle ND, Miner ME, Hall WA, Siegal T, Jerome E, Osztie E, McAllister LD, Bubalo JS, Kraemer DF, Fortin D, Nixon R, Muldoon LL, Neuwelt EA. Safety and efficacy of a multicenter study using intraarterial chemotherapy in conjunction with osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier for the treatment of patients with malignant brain tumors. Cancer. 2000;88:637–647. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<637::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroll RA, Neuwelt EA. Outwitting the Blood-Brain Barrier for Therapeutic Purposes: Osmotic Opening and Other Means. 1998;42:1083–1099. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199805000-00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology. 2001;220:640–646. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2202001804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JJ, Pernot M, Small SA, Konofagou EE. Non-invasive, transcranial and localized opening of the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound in mice. Ultr. Med. Biol. 2007;33:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi JJ, Feshitan JA, Baseri B, Wang S, Tung YS, Borden MA, Konofagou EE. Microbubble-Size Dependence of Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Mice In Vivo. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2010;57:145–154. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2034533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JJ, Wang S, Tung YS, Morisson B, III, Konofagou EE. Molecules of various pharmacologically-relevant sizes can cross the ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in vivo. Ultr Med Biol. 2010;36:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheikov N, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Cellular mechanisms of the blood-brain barrier opening induced by ultrasound in presence of microbubbles. Ultr. Med. Biol. 2004;30:979–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikov N, McDannold N, Sharma S, Hynynen K. Effect of focused ultrasound applied with an ultrasound contrast agent on the tight junctional integrity of the brain microvascular endothelium. Ultr. Med. Biol. 2008;34:1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tung YS, Choi JJ, Baseri B, Konofagou EE. Identifying the inertial cavitation threshold and skull effects in a vessel phantom using focused ultrasound and microbubbles. Ultr Med Biol. 2010;36:840–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tung YS, Vlachos F, Choi JJ, Deffieux T, Selert K, Konofagou EE. In vivo transcranial cavitation threshold detection during ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening in mice. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:6141–6155. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/20/007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baseri B, Choi JJ, Tung YS, Konofagou EE. Multi-Modality Safety Assessment Of Blood-Brain Barrier Opening Using Focused Ultrasound And Definity Microbubbles: A Short-Term Study. Ultr Med Biol. 2010;36:1445–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hynynen K, McDannold N, Martin H, Jolesz F, Vykhodtseva N. The threshold for brain damage in rabbits induced by bursts of ultrasound in the presence of an ultrasound contrast agent (Optison) Ultr Med Biol. 2003;29:473–481. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00741-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu HL, Wai YY, Chen WS, Chen JC, Hsu PH, Wu XY, Huang WC, Yen TC, Wang JJ. Hemorrhage detection during focused-ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening by using susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ultr Med Biol. 2008;34:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlachos F, Tung YS, Konofagou EE. Permeability assessment of the focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:5451–5466. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/18/012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tofts PS, Kermode AG. Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability and leakage space using dynamic MR imaging: 1. Fundamental concepts. Magn Res Med. 1991;17:357–367. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feshitan JA, Chen CC, Kwan JJ, Borden MA. Microbubble size isolation by differential centrifugation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;329:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JJ, Selert K, Gao Z, Samiotaki G, Baseri B, Konofagou EE. Noninvasive and localized blood–brain barrier disruption using focused ultrasound can be achieved at short pulse lengths and low pulse repetition frequencies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howles GP, Bing KF, Qi Y, Rosenzweig SJ, Nightingale KR, Johnson GA. Contrast-enhanced in vivo magnetic resonance microscopy of the mouse brain enabled by noninvasive opening of the blood-brain barrier with ultrasound. Magn Res Med. 2010;64(4):995–1004. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, Larsson HB, Lee TY, Mayr NA, Parker GJ, Port RE, Taylor J, Weisskoff RM. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10(3):223–232. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath DM, Bradley DP, Tessier JL, Lacey T, Taylor CJ, Parker GJ. Comparison of model-based arterial input functions for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in tumor bearing rats. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(5):1173–1184. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker GJM, Buckley DL. Tracer kinetic modeling for T1-weighted DCE-MRI. In: Jackson A, Buckley DL, Parker GJM, editors. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in oncology. Medical radiology diagnostic imaging. Berlin: Springer; 2005. pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas DL, Lythgoe MF, Gadian DG, Ordidge RJ. In vivo measurement of the longitudinal relaxation time of arterial blood (T1a) in the mouse using a pulsed arterial spin labeling approach. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:943–947. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilgen M, Dogan B, Narayana PA. In vivo assessment of blood-spinal cord barrier permeability: serial dynamic contrast enhanced MRI of spinal cord injury. Magn Reson Imag. 2002;20:337–341. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pellerin M, Yankeelov TE, Lepage M. Incorporating Contrast Agent Diffusion Into the Analysis of DCE-MRI data. Magn Res Med. 2007;58:1124–1134. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahnke H, Schaeffter T. Limits of detection of SPIO at 3.0 T using T2 relaxometry. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1202–1206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker GJ, Roberts C, Macdonald A, Buonaccorsi GA, Cheung S, Buckley DL, Jackson A, Watson Y, Davies K, Jayson GC. Experimentally-derived functional form for a population-averaged high-temporal-resolution arterial input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(5):993–1000. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yankeelov TE, Luci JJ, Lepage M, Li R, Debusk L, Lin PC, Price RR, Gore JC. Quantitative pharmacokinetic analysis of DCE-MRI data without an arterial input function: a reference region model. Magn Res Med. 2005;23(4):519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor JS, Toft PS, Port R, Evelhoch JL, Knopp M, Reddick WE, Runge VM, Mayr N. MR Imaging of Tumor Microvasculature: Promise of the New Millenium. J Magn Res Imag. 1999;10:903–907. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199912)10:6<903::aid-jmri1>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilgen M, Narayana PA. A pharmacokinetic model for quantitative evaluation of spinal cord injury with dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Res Med. 2001;46(6):1099–1106. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchette M, Pellerin M, Tremblay L, Lepage M, Fortin D. Real-Time Monitoring of Gadolinium Diethylenetriamine Penta-Acetic Acid During Osmotic Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Normal Wistar Rats. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(2):344–351. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000349762.17256.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yankeelov TE, Luci JJ, Debusk LM, Lin PC, Gore JC. Incorporating the effects of transcytolemmal water exchange in a reference region model for DCE-MRI analysis: Theory, simulations, and experimental results. Magn Res Med. 2008;59(2):326–35. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]