Abstract

Diabetes mellitus results from immune cell invasion into pancreatic islets of Langerhans, eventually leading to selective destruction of the insulin-producing β-cells. How this process is initiated is not well understood. In this study, we investigated the regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes, which encode proteins that promote migration of CXCR2+ cells, such as neutrophils, toward secreting tissue. Herein, we found that IL-1β markedly enhanced the expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in rat islets and β-cell lines, which resulted in increased secretion of each of these proteins. CXCL1 and CXCL2 also stimulated the expression of specific integrin proteins on the surface of human neutrophils. Mutation of a consensus NF-κB genomic sequence present in both gene promoters reduced the ability of IL-1β to promote transcription. In addition, IL-1β induced binding of the p65 and p50 subunits of NF-κB to these consensus κB regulatory elements as well as to additional κB sites located near the core promoter regions of each gene. Additionally, serine-phosphorylated STAT1 bound to the promoters of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes. We further found that IL-1β induced specific posttranslational modifications to histone H3 in a time frame congruent with transcription factor binding and transcript accumulation. We conclude that IL-1β-mediated regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in pancreatic β-cells requires stimulus-induced changes in histone chemical modifications, recruitment of the NF-κB and STAT1 transcription factors to genomic regulatory sequences within the proximal gene promoters, and increases in phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II.

autoimmune diseases are often categorized as systemic, such as rheumatoid arthritis, or organ specific, such as type 1 diabetes mellitus [T1DM (49)]. Both types of autoimmune diseases arise through inappropriate immune cell targeting of a self tissue. In the case of T1DM, leukocyte infiltration into the pancreatic islets culminates with the destruction of the insulin-producing β-cells (42). This loss in functional islet β-cell mass leads to the clinical symptoms associated with T1DM. The eradication of islet β-cells requires multiple immune cell types, with T cells and macrophages being among the best known contributors to T1DM (13, 46, 57). The accumulation of these immune cells in pancreatic islets is referred to as inflammatory insulitis and is a hallmark of T1DM (13–14, 29, 45) and is beginning to be recognized in lipid overload and T2DM (25–26).

A logical basis for initiating and/or maintaining leukocyte infiltration into pancreatic islets is the production and secretion, by β-cells themselves, of chemotactic proteins that control recruitment of immune cells into the islet tissue (7, 18, 65). Indeed, studies using transgenic mice reveal that monocytes and macrophages are recruited into pancreatic islets by β-cell release of the chemokine CCL2 (50), while CXCL10 secretion from insulin-producing cells promotes T cell infiltration (60). Macrophages and various T cell populations are known to participate in autoimmune-mediated β-cell destruction in both rodents and humans (9, 13, 28, 46). However, how this process is initially instigated is not well understood.

It has only recently become apparent that the interplay of other immune cells, including B cells, dendritic cells, and neutrophils, is also a critical component of the initiation of autoimmune-mediated β-cell destruction (22). Neutrophils are highly abundant in the circulation and rapidly respond to inflammatory stimuli to provide host defense against many microorganisms (53). In addition to their role in maintenance of host homeostasis, neutrophils also contribute to the development of many different autoimmune diseases (54). Similar to macrophages and T cells, neutrophils can be recruited to sites of inflammation by specific chemokines (2).

Neutrophils express the CXCR1 and CXCR2 chemokine receptors. CXCR2 is activated by a variety of chemokine ligands, including CXCL1 and CXCL2 (3). The CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes are expressed in both rodent and human islets in response to proinflammatory cytokines (18, 65). Moreover, these two chemokines are strongly linked to a variety of autoimmune diseases, including T1DM (72). Indeed, CXCL1 levels are elevated in the blood of both rodents and humans with T1DM (71) and in humans with type 2 diabetes mellitus (64). In addition, pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion of the CXCR2 receptor improves islet graft survival and function (10). However, the regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in pancreatic β-cells by inflammatory signals, such as IL-1β, is not well understood.

IL-1β induces a variety of signaling pathways linked to inflammatory responses (31) and directly contributes to β-cell death and dysfunction (57). IL-1β-induced activation of the NF-κB pathway is one of the central signaling cascades leading to the alterations in gene transcription that promote islet inflammation. NF-κB transcriptional regulatory proteins include p65/RelA, RelB, c-Rel, p50, and p52 (56). This family of transcription factors forms homo- or heterodimers to alter gene expression patterns, many of which are associated with inflammatory processes (69). Therefore, although IL-1β and NF-κB strongly correlate with a distinct variety of autoimmune diseases through systems biology analyses (72), the molecular mechanisms underlying regulation of genes controlling inflammatory processes have not been fully delineated. Herein, we report that IL-1β requires NF-κB and STAT1 for transcriptional regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes and that specific posttranslational modifications to histone proteins are associated with IL-1β-mediated alterations in gene transcription patterns.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, islet isolation, and reagents.

The 832/13 rat insulinoma cell line was cultured as previously described (36). Isolation of islets from Wistar rats has also been described (12). IL-1β was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), and IFNγ was from Shenandoah Biotechnology (Warwick, PA). TPCA was from Tocris Bioscience (Elllisville, MO). Recombinant adenoviruses expressing β-galactosidase (35), 5× NF-κB-luciferase (7), and IκBα S32A/S36A (40) are described elsewhere. The adenovirus encoding IκKβ/S177E/S181E was a generous gift from Dr. Haiyan Xu (Brown University).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from cell lines using Isol-RNA Lysis Reagent (5 Prime Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), and from rat islets using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized using the Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). iTAQ Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used for real-time RT-PCR analysis. Analysis of real-time PCR data was done using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method also commonly referred to as the ΔΔCT method (67). Primers used to detect transcript levels of RS9, CXCL1and CXCL2 were designed using Primer3Plus software and are available upon request.

Plasmid construction.

The CXCL1 promoter-reporter luciferase plasmid was constructed by PCR amplifying −1.5 kb of the CXCL1 promoter using rat genomic DNA as a template, AmpliTaq Gold 360 DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and the following primer pair: (F) 5′-CAGAGGGAGGCCCATCAT-3′ and (R) 5′-GGAGTGTGGCTGGAGTCT-3′. The resulting amplicon was inserted into the TOPO TA cloning vector (Life Technologies) and then subcloned into pGL3 Basic using the SacI and XhoI sites in both vectors. The CXCL2 −1.5-luciferase reporter plasmid was constructed by similar methods using the following primer pair: (F) 5′-CAAAACCCAGGGTGAGAACT-3′ and (R) 5′-CTTGAAGTCAACCCTTGGTAGG-3′.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to incorporate mutations within the conserved NF-κB response elements of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 −1.5-kb-luciferase plasmids. The following primer pairs were used to incorporate these mutations: CXCL1: (F) 5′-GGAGTTTGGGAGTTCTGGAAccTCCCGAGTTCAAAAAGCAAAG-3′ and (R) 5′-CTTTGCTTTTTGAACTCGGGAggTTCCAGAACTCCCAAACTCC-3′. CXCL2: (F) 5′-CACTGGAGCCTCGGAAccTCCCGAATTTCACAG-3′ and (R) 5′-CTGTGAAATTCGGGAggTTCCGAGGCTCCAGTG-3′. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Molecular Biology Resource Facility at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Transfection and luciferase assays.

Transfection of plasmid and siRNA duplexes into 832/13 cells, harvesting of cellular lysates, luciferase reporter activity determination, and measurement of total protein content were all described previously (7, 11). Silencer Select siRNA duplexes (Life Technologies) used in this study are as follows: negative control siScramble (M4611), sip65 (siRNA ID no. s159516 and s159517) and (mutations are shown in lowercase and underlined) sip50 (siRNA ID no. s135617).

ELISA.

Secretion of CXCL1 and CXCL2 into the culture medium was detected using Quantikine kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. CXCL1 and CXCL2 release into the medium was normalized to total protein to account for any potential variability in cell number.

Neutrophil migration.

Peripheral blood neutrophils (PBN) were isolated from EDTA-treated blood from healthy human volunteers by using dextran sedimentation and density gradient centrifugation as previously described (48). Erythrocytes were lysed with hypotonic lysis in 0.2% NaCl. PBN were resuspended in HBSS with 0.1% BSA and 10 mM HEPES, and 20 μl of 10 nM CXCL1 or a 1:10 dilution of β-cell supernatants from IL-1β-treated or untreated cells were loaded into the lower well of the 96-well modified Boyden chamber (Neuroprobe, Gaithersburg, MD) and fitted with a 5-μm filter. PBN were labeled with 1 ng/ml CalceinAM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 400 nM of SB225002 (Millipore) or DMSO control for 0.5 h on a rotating wheel at 37°C. Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended to 1 × 106 cells/ml in HBSS with SB225002 (400 nM) or DMSO control. Then, 30 μl of the cell suspension was added to the upper well. The cells were then incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. Migration of PBN was measured with a fluorescent plate reader (Synergy 2, Biotek) using Ex/Em wavelength 495/515. The fluorescence from buffer only (no chemokine) control wells was the background migration. The use of human subjects for neutrophil isolation was approved by the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 6476B).

Integrin expression.

PBNs (1 × 106), isolated as described above, were stained with varying concentrations of CXCL1, CXCL2, or both. After a 2-h incubation, cells were stained for integrin expression using a 1:6 dilution of directly conjugated antibodies [CD11a-PerCP, CD11b-APC, CD11c-PE (Biolegend) (52)]. After a 2-h incubation, cells were washed and fixed with paraformaldehyde for 10 min. The abundance of integrin expression was analyzed via flow cytometry (BD FACsCalibur) followed by FlowJo analysis (Tree Star).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

ChIP assays and analysis of downstream data were performed as described previously (5, 8). Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation of acetylated histone H3 (K9 and K14) and H4 (K5, K8, K12, and K16), methylated histone H3 (K4, 9 and 27), and acetylated histone H3 (K14) were from Millipore, while p65 and p50 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Normal rabbit and mouse serum (control IgG) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Primers used for detection of recovered DNA were designed using Primer3 Plus software and are available upon request.

Protein isolation and immunoblot analysis.

Cellular lysates were harvested using the M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with a cocktail of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). Proteins were quantified using a BCA assay (Thermo Scientific), and immunoblotting was performed as previously described (11). Antibodies used for detection of proteins were from the following manufacturers: Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (PO4-IκBα and IκBα), Cell Signaling (PO4-Y701 STAT1), and Sigma-Aldrich (β-actin).

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed on the data using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc correction. Statistical significance is reported in the individual figure legends with confidence intervals denoted. All calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

RESULTS

IL-1β increases the expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in rat islets and β-cell lines.

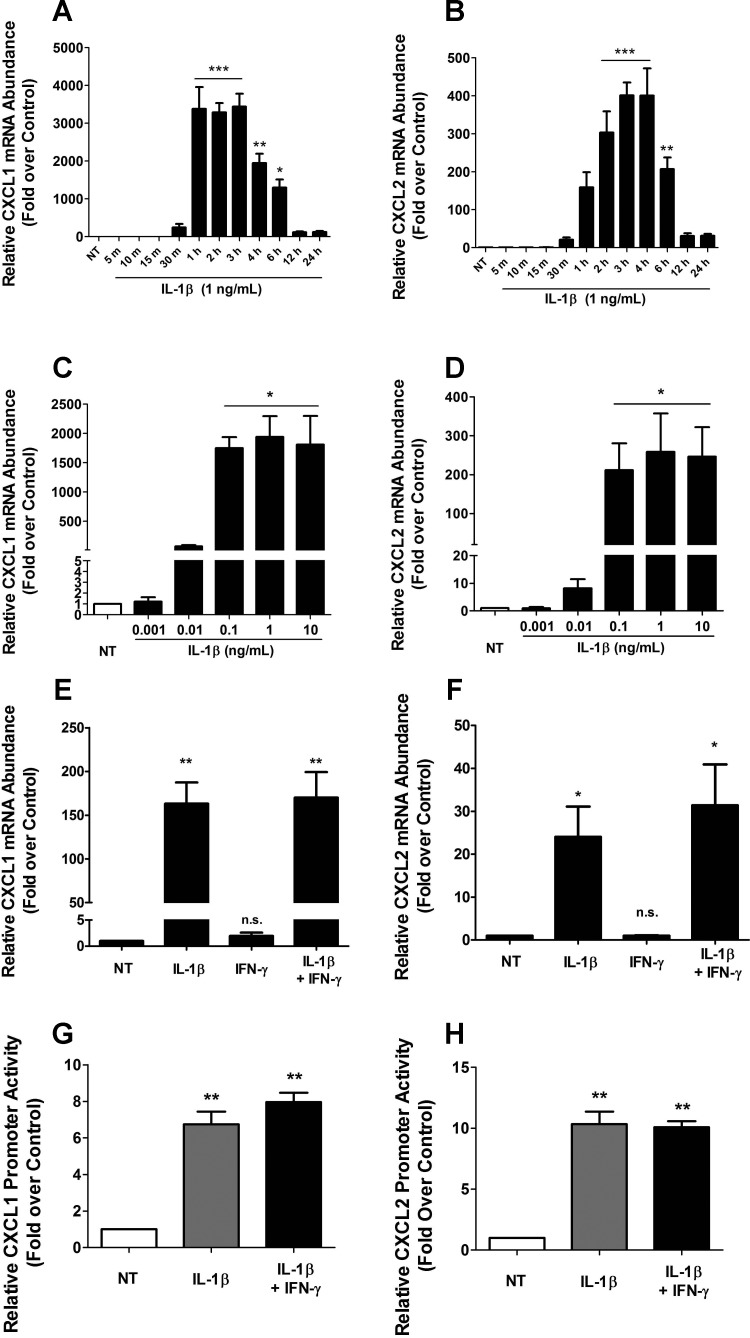

CXCL1 and CXCL2 levels are elevated in human islets exposed to cytokines (18, 65) and in individuals with diabetes mellitus (34, 68). Thus, we investigated the signals that increase the expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes by using rat islets and β-cell lines. We found that 1 ng/ml IL-1β induced the first appearance of transcript encoding the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes over baseline within 30 min in 832/13 rat insulinoma cells (Fig. 1, A and B). Expression of the CXCL1 gene peaked at 1 h, whereas maximal expression of the CXCL2 gene was at 3 h (Fig. 1, A and B). Furthermore, the response of these genes to IL-1β is not sensitive to cycloheximide, indicating that new protein synthesis is most likely not required for signal-induced transcription of these two genes (data not shown). A similar response was obtained in the INS-1E rat insulinoma cell line (not shown). We have previously reported that 1 ng/ml IL-1β is required to drive maximal expression of the COX2 and CCL2 genes (4, 7). In addition, 1 ng/ml IL-1β is also the saturation point for 832/13 cell death (11). However, the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes respond to a 10-fold lower dose of IL-1β, displaying robust and maximal gene expression at 0.1 ng/ml of this cytokine (Fig. 1, C and D). In addition, IL-1β also increased CXCL1 and CXCL2 mRNA levels in isolated rat islets (Fig. 1, E and F), results that are consistent with those reported in human islets (65).

Fig. 1.

Cytokine-mediated activation of CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in the 832/13 rat β-cell line and isolated rat islets. A and B: 832/13 cells were untreated (NT) or treated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for indicated times. C and D: 832/13 cells were untreated or treated with increasing concentrations of IL-1β for 3 h. E and F: rat islets were untreated or treated with 10 ng/ml IL-1β, 100 U/ml IFNγ or both cytokines for 6 h. A–F: CXCL1 (A, C, E) and CXCL2 (B, D, F) mRNA levels were measured and normalized to those of the housekeeping gene ribosomal S9 (RS9). *P < 0.05 vs. NT (A, C, D, F), **P < 0.01 vs. NT (A, B, E), ***P < 0.001 vs. NT (A, B); n.s., not significant vs. NT (E, F). G and H: 832/13 cells were transfected with 1.5 kb of the CXCL1 (G) or CXCL2 (H) promoter upstream of the transcriptional start site fused to a luciferase reporter. Posttransfection (24 h), cells were untreated or stimulated for 4 h with 1 ng/ml IL-1β or IL-1β + 100 U/ml IFNγ. Relative promoter luciferase activity is shown. **P < 0.01 vs. NT (G, H). Data are presented as means ± SE from 3–4 individual experiments.

To examine the transcriptional responses of each gene, we cloned 1.5 kb of the genomic DNA sequence upstream of the transcriptional start site, which corresponds to the proximal gene promoters of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes. Transfection of the CXCL1 promoter-luciferase reporter construct into 832/13 cells revealed a 6.7-fold response to 1 ng/ml IL-1β with no further potentiation by IFNγ (Fig. 1G). The activity of the CXCL2 gene promoter was induced 10.3-fold upon stimulation with 1 ng/ml IL-1β (Fig. 1H). These results are also consistent with the CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcript profiling obtained using mouse and human islets (18).

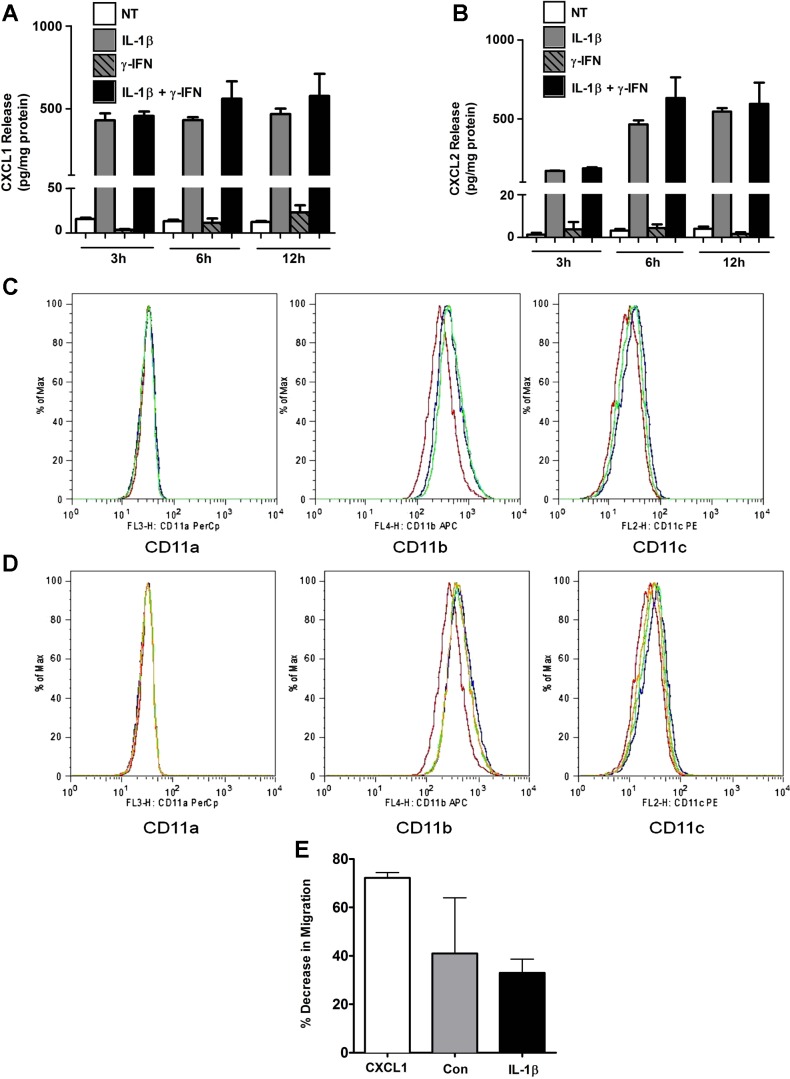

We next used ELISA to determine the quantity of CXCL1 and CXCL2 protein being secreted in response to IL-1β, IFNγ, or a combination of these cytokines. The secretion of CXCL1 was robust and rapid after cellular incubation with 1 ng/ml IL-1β, with a 28-fold increase in secreted protein within 3 h (Fig. 2A). In addition, CXCL2 protein release was induced 132-fold by IL-1β at 3 h and rose to 464-fold at 6 h (Fig. 2B). These results are consistent with the kinetics of transcript accumulation shown in Fig. 1, A and B. We further note that IFNγ did not augment the synthesis or secretion of either CXCL1 or CXCL2. Thus, IL-1β appears to be the predominant signal controlling synthesis and secretion of CXCL1 and CXCL2 in pancreatic β-cells.

Fig. 2.

IL-1β promotes release of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 chemokines and activates peripheral blood neutrophils (PBN) for integrin expression and migration via CXCR2. A and B: 832/13 cells were untreated or treated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β, 100 U/ml IFNγ, or the combination of both cytokines for 0, 3, 6, and 12 h. CXCL1 (A) and CXCL2 (B) release into culture medium was measured by ELISA and normalized to protein content via BCA assay. Values are presented as means ± SE from 3 individual experiments. PBN were unstimulated (PBS control, red lines) or exposed to CXCL1 (blue) or CXCL2 (green) at 100 nM and the level of expression of intergrins CD11a, CD11b, or CD11c measured by flow cytometry (C). PBNs were unstimulated (red) or incubated with a combination of CXCL1/CXCL2 at (1 nM/10 nM, green lines) or CXCL1/CXCL2 at 10 nM/1 nM (blue lines), and levels of integrin expression were measured (D). Plots are representative experiments from 3 replicates. PBNs were exposed to human CXCL1 (10 nM) or 1:10 dilutions of supernatants from control 832/13 (Con) or IL-β exposed (IL-1β) in the presence of CXCR2 inhibitor SB225002 (400 nM) in a chemotaxis assay (E). Bars, are average decrease in migration in the presence of the CXCR2 inhibitor relative to control with no inhibitor. Each bar is the average of 4–6 duplicates ± SD from 6 biological replicates.

Because the pancreatic β-cell produces a variety of chemokines in response to IL-1β (7, 65), we used recombinant CXCL1 or CXCL2 to test the efficiency of these chemokines either in isolation or in combination with each other on PBN function. PBNs express integrins CD11a (LFA-1), CD11b (Mac-1), and CD11c (ITGAX, αX) for attaching to the endothelial surface prior to extravasation out of the blood stream (78). Integrins are members of a superfamily of heterodimers that are responsible for cellular adhesion to the extracellular matrix. Either CXCL1 or CXCL2 alone was sufficient to induce neutrophil surface expression of integrins CD11b and CD11c, but not CD11a (Fig. 2C and data not shown). Combining these chemokines in differing ratios of CXCL1/CXCL2 (1/10, 10/10, 10/1 nM) did not further enhance integrin surface expression over either chemokine alone (Fig. 2D and data not shown). We further found that human blood neutrophils migrate in response to either CXCL1 or CXCL2 recombinant proteins in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown). However, interfering with the activity of CXCR2 by using the allosteric inhibitor SB225002 markedly reduced the migration of neutrophils in response to recombinant CXCL1 (72%) and in response to β-cell supernatants (41% for control and 33% for IL-1β exposure, respectively; Fig. 2E) Taking the data from Figs. 1 and 2 together, we conclude that IL-1β promotes synthesis and secretion of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in pancreatic β-cells and that these proteins enhance the expression of integrins at the neutrophil cell surface as well as promote cell migration through CXCR2.

NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 and a consensus κB sequence are required for transcription of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in response to IL-1β.

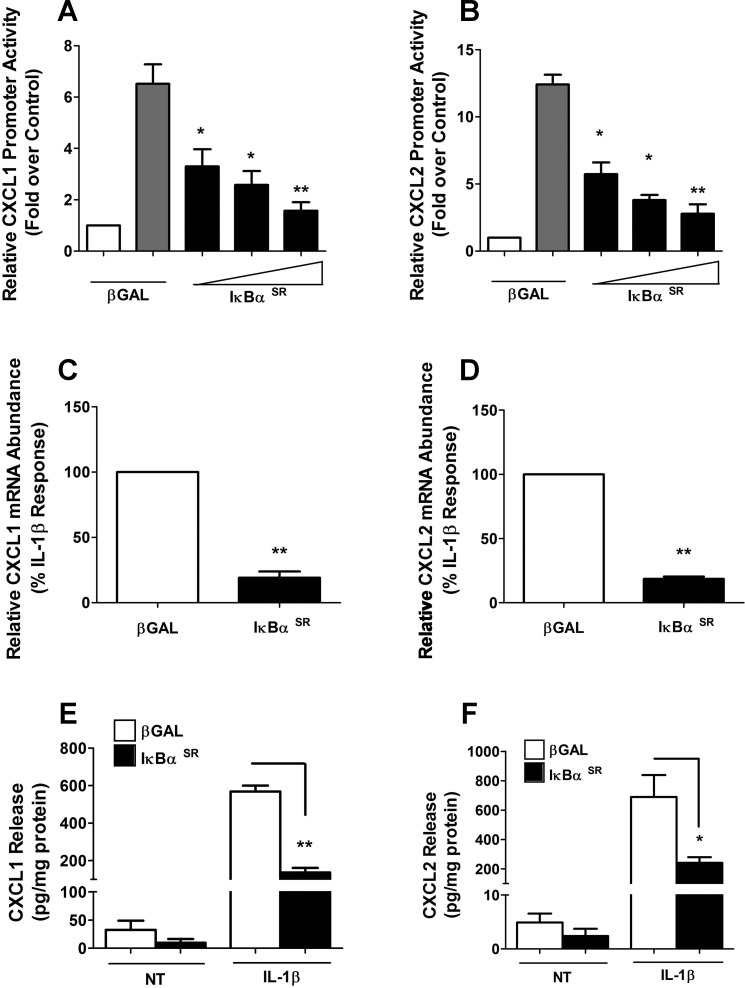

To identify components required for signal integration at the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters, we first targeted NF-κB signaling using the IκBα superrepressor (SR), a protein with mutations that render it resistant to stimulus-induced degradation (40). Overexpression of the IκBαSR in 832/13 cells blocked IL-1β-mediated transcriptional activity of the CXCL1 gene promoter (Fig. 3A). We detected 53, 61, and 75% decreases in promoter activity with increasing doses of the IκBαSR. In addition, we noted 54, 73, and 74% decreases in the ability of IL-1β to drive CXCL2 transcriptional activity in the presence of the IκBαSR (Fig. 3B). This was also true for the endogenous genes, as the CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcripts were decreased 81 and 82%, respectively, in the presence of the IκBαSR (Fig. 3, C and D). The diminution in gene expression and promoter activity also corresponds to 76 and 65% decreases in secreted CXCL1 and CXCL2 proteins (Fig. 3, E and F).

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of a mutant IκBα protein blocks cytokine-mediated activation and secretion of both CXCL1 and CXCL2. A and B: 832/13 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids containing −1.5 kb of CXCL1 (A) and CXCL2 (B) promoters. Posttransfection (4 h), adenoviruses expressing βGAL or IκBαSR (SR, superrepressor, which denotes S32A/S36A mutations) were transduced and cultured overnight. Cells were then untreated (open bars) or stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 4 h (gray and filled bars). Relative promoter luciferase activity normalized to total protein is shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL (gray bars). C and D: 832/13 cells were treated with indicated adenoviruses for 12 h and then stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 6 h. Relative mRNA abundance of CXCL1 and CXCL2 was normalized to RS9. **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL (C, D). E and F: 832/13 cells were treated with indicated adenoviruses. Postadenoviral transduction (12 h), cells were treated with IL-1β for an additional 12 h. CXCL1 (E) and CXCL2 (F) release into medium was measured by ELISA and normalized to protein content via BCA assay. **P < 0.01 (E), *P < 0.05 (F). Data are shown as means ± SE from 3 individual experiments.

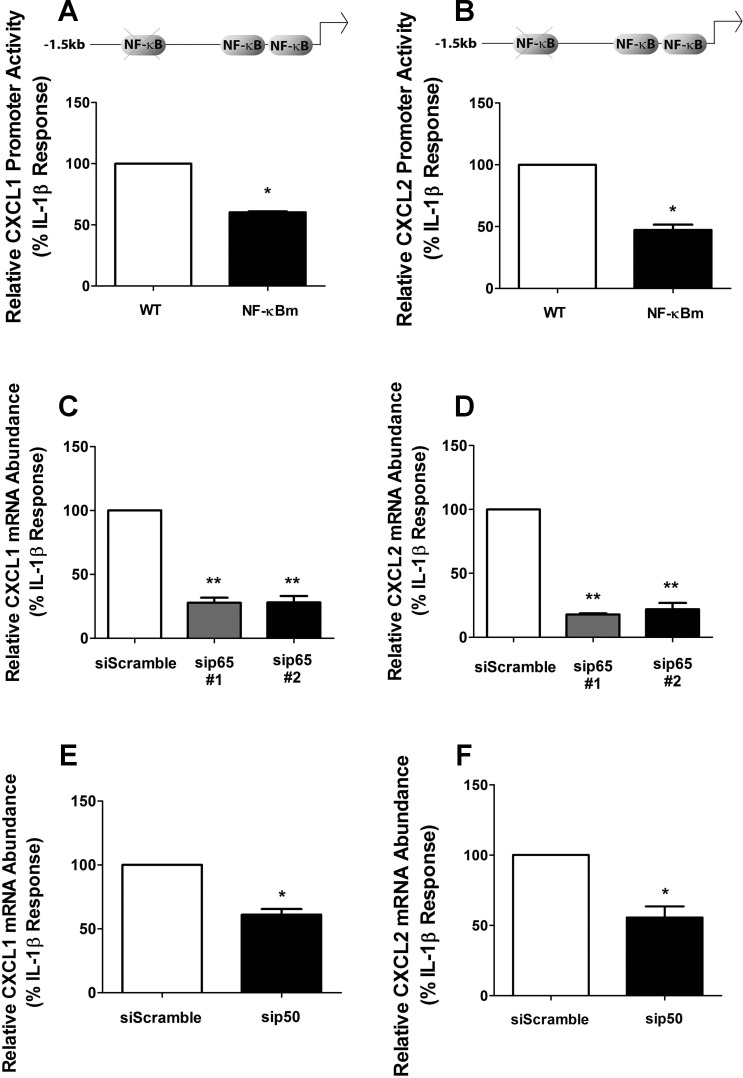

Because the experimental approach with IκBαSR indicated that NF-κB proteins are critical for expression of each gene, we used transcription factor search algorithms to predict known regulatory response elements within the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters. We observed several predicted κB sequences for each gene and discovered a conserved consensus κB site with an identical sequence in both CXCL1and CXCL2 promoters at positions −641 (CXCL1) and −640 (CXCL2) (relative to the transcriptional start site; results shown in Table 1). Mutating this consensus κB sequence decreased CXCL1 (40%) and CXCL2 (53%) gene transcription in response to IL-1β (Fig. 4, A and B).

Table 1.

Predicted NF-κB sequences in the rat CXCL1 and CXCL2 proximal gene promoters

| CXCL1 | CXCL2 | CXCL1/CXCL2 |

|---|---|---|

| GGGAATTTCCC | GGGGCTTTTCC | −83/−54 |

| GGGAAACACCC | GGGGATTTCCC | −102/−73 |

| GGAAGTTCCC | GGAAGTTCCC | −641/−640 |

| TGGACTTTCC | ND | −709/ND |

| GGGATTTGCT | ND | −1299/ND |

For each gene, TFSEARCH (v. 1.3) was used to analyze ∼1.5 kb of the upstream promoter region (relative to the transcriptional start site) for recognized κB genomic regulatory sequences. Predicted κB sequences for each gene are shown in the left (CXCL1) and middle (CXCL2) columns, with a comparison of relative positioning of each detected κB site shown at the right. Bolded sequence is a consensus κB response element detected in both genes at almost identical genomic positions. ND, no comparable site detected by the software algorithm within that region. Consensus κB sequence: GGRRNNYYCC, where R is purine, N is any nucleotide, and Y is pyrimidine.

Fig. 4.

NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 are required for cytokine-dependent activation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes. A and B: 832/13 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing −1.5 kb of the CXCL1 (A) or CXCL2 (B) promoters (WT) or similar-length constructs wherein upstream conserved NF-κB response elements were mutated (NF-κBm; as shown in schematic). Posttransfection (24 h), cells were stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 4 h and luciferase activity was quantified. *P < 0.05 vs. WT (A, B). C–F: 832/13 cells were transfected with duplexes against p65 (C, D) or p50 (E, F), using a scrambled siRNA sequence duplex as a control. Posttransfection (48 h), cells were treated for 6 h with 1 ng/ml IL-1β. Relative CXCL1 and CXCL2 mRNA levels were normalized to RS9. **P < 0.01 vs. siScramble (C, D), *P < 0.05 vs. siScramble (E, F). Data are expressed as means ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

Since heterodimers of p65/p50 are considered the major dimer species controlling signal-specific transcriptional activation (32), we next used siRNA-directed suppression of the p65 and p50 NF-κB subunits. Upon duplex transfection, p65 transcript levels were decreased by 71%, resulting in a marked loss in p65 protein abundance (not shown). This maneuver resulted in a 73% decrease in CXCL1 mRNA abundance (Fig. 4C). In addition, the CXCL2 gene was decreased by 83 and 80%, using two different siRNA sequences targeting different exons of the p65 transcript (Fig. 4D). Similarly, siRNA-mediated suppression of p50 also decreased the IL-1β-induced expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes by 42 and 38%, respectively (Figs. 4, E and F). Thus, IL-1β controls the expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes, using the p65 and p50 subunits of NF-κB and a conserved κB binding site located in their proximal gene promoter regions.

The inhibitor of κB kinase-β is necessary and sufficient for activation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes.

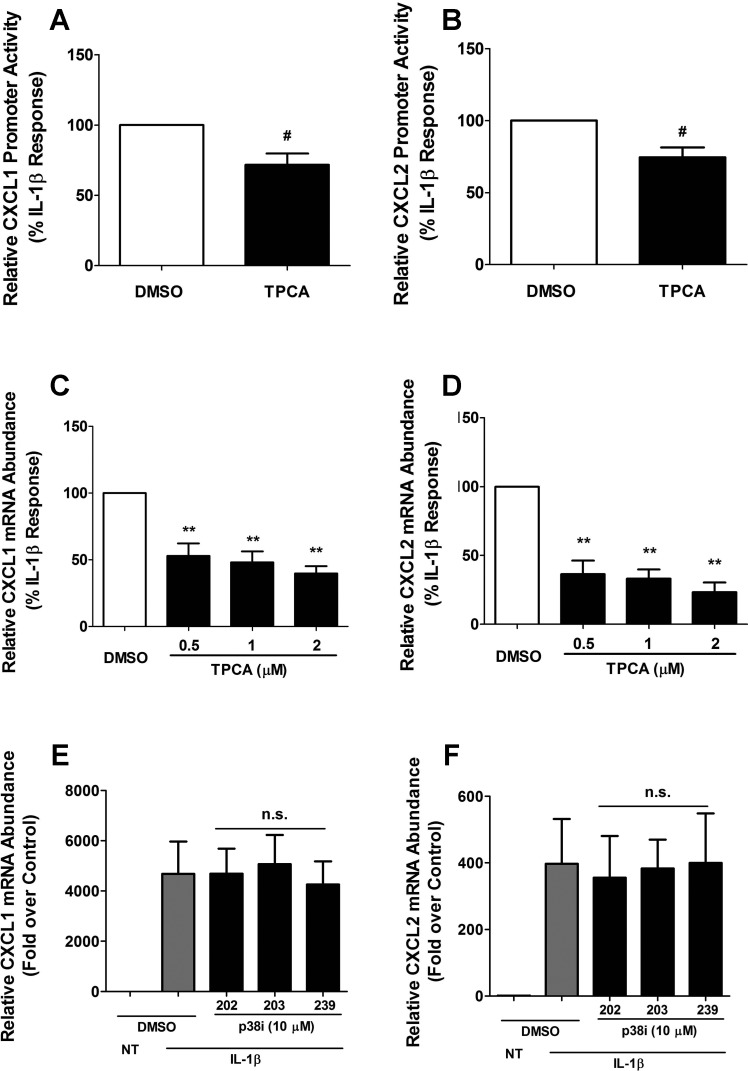

The inhibitor of κB kinase-β (IκKβ) is a major convergence point for regulation of NF-κB signaling (32, 38) and also modulates the viability of pancreatic β-cells upon exposure to IL-1β (11). To investigate whether IκKβ is involved in mediating the increase in expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in response to IL-1β, we used the small molecule inhibitor 2-[(aminocarbonyl)amino]-5-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-thiophenecarboxamide (TPCA) to inhibit IκKβ (59). We observed that the IL-1β-mediated enhancement in transcriptional activity at the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters was decreased (35 and 32%, respectively) with the addition of TPCA (Fig. 5, A and B). Additionally, IL-1β induced steady-state mRNA accumulation of the CXCL1 gene was diminished 47, 52, and 61% in the presence of TPCA (Fig. 5C), and CXCL2 transcript was reduced by 64, 67, and 77% under the same conditions (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that IκKβ is necessary for IL-1β signaling-induced increases in the expression of each of these chemokine genes.

Fig. 5.

IκKβ inhibition impairs IL-1β-mediated induction of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes. A and B: 832/13 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing −1.5 kb of CXCL1 (A) or CXCL2 (B) promoters. The next day, cells were pretreated for 1 h with 2 μM TPCA and then stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 4 h. Cells were lysed, and CXCL1 and CXCL2 promoter luciferase activity was quantified. #P < 0.1 vs. DMSO (A, B). C and D: 832/13 cells were pretreated for 1 h with 0.5, 1, or 2 μM TPCA, followed by 6 h stimulation with 1 ng/ml IL-1β. Relative CXCL1 and CXCL2 mRNA abundance was normalized to RS9. **P < 0.01 vs. DMSO (C, D). E and F: 832/13 cells were pretreated individually for 1 h with 10 μM of 3 different p38 inhibitors (SB202190, SB203580, and SB239063) followed by 6 h incubation with 1 ng/ml IL-1β. Relative mRNA abundance of CXCL1 and CXCL2 was calculated; n.s. vs. DMSO (E, F). Data shown represent means ± SE from 3 individual experiments.

Alternatively, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is not involved in induction of either the CXCL1 or CXCL2 genes in response to IL-1β (Fig. 5, E and F). Using three different pyridinyl imidazole-based inhibitors, which effectively reduce the expression of the CCL2 gene upon exposure to IL-1β (Ref 7 and data not shown), we saw no loss in transcript abundance.

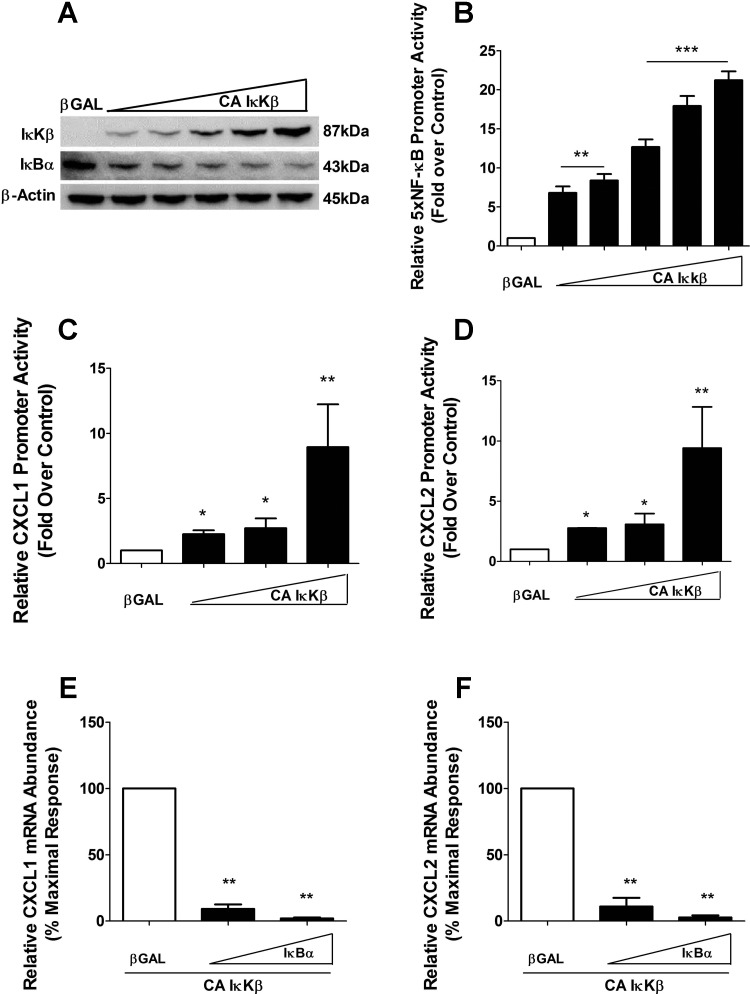

To determine whether or not IκKβ was sufficient for induction of the CXCL1 or CXCL2 genes, we overexpressed a constitutively active version of the kinase (CA IκKβ). This adenoviral construct expresses IκKβ with S177E/S181E substitutions to create a constitutively active kinase (19, 51). We detected dose-dependent expression of the mutant protein, which corresponded to degradation of IκBα protein (Fig. 6A), a known target of IκKβ (38). Expression of CA IκKβ was also capable of driving transcription from a multimerized NF-κB promoter luciferase reporter gene in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

IκKβ drives expression of CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes. A: 832/13 cells were transduced with βGAL or 5 increasing concentrations of IκKβ S177E/S181E (CA IκKβ) overnight. Whole cell lysates were harvested, and immunoblot analysis was performed using antibodies directed against IκKβ, IκBα, and β-actin. B: cells were transfected with 5× NF-κB-Luc and subsequently transduced with indicated adenoviruses (the same concentrations as in Fig. 6A); relative promoter luciferase activity was measured. **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL, ***P < 0.001 vs. βGAL. C and D: 832/13 cells were transfected with −1.5kb-luciferase plasmids (C, CXCL1; D, CXCL2), and 4 h posttransfection, cells were stimulated with adenoviruses expressing βGAL or 3 increasing doses of CA IκKβ. Doses shown correspond to the 3 highest doses seen in the immunoblot for a further 12 h. At the end of the 12 h, cells were lysed and CXCL1 and CXCL2 promoter activity was quantified. *P < 0.05 vs. βGAL, **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL. E and F: 832/13 cells were treated with adenoviruses expressing CA IκKβ and either βGAL or 2 increasing concentrations of IκBαSR (IκBα). CXCL1 (E) and CXCL2 (F) mRNA levels were measured and normalized to those of RS9. **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL. Data shown represent means ± SE from 3 independent experiments. The immunoblot in A is representative of 2 independent experiments.

We next examined whether expression of CA IκKβ was capable of increasing transcription from luciferase reporter constructs driven specifically by the CXCL1 or CXCL2 proximal gene promoters. These experiments were performed in the absence of cytokines. Indeed, we detected 2.3-, 2.7-, and 8.8-fold enhancements in promoter activity on the CXCL1 reporter gene (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the CXCL2 reporter gene displayed 2.7-, 3.0-, and 8.0-fold increases in promoter activity in the presence of the CA IκKβ (Fig. 6D). The CA IκKβ also increased the abundance of the endogenous CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcripts; this expression was completely blocked by the IκBαSR (Fig. 6, E and F), which confirms that the gene expression promoted by CA IκKβ is through downstream NF-κB proteins. In addition, CA IκKβ further enhances the IL-1β-induced increases in CXCL1 and CXCL2 mRNA (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that IκKβ participates in the regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes and is both necessary and sufficient to promote expression of these two genes.

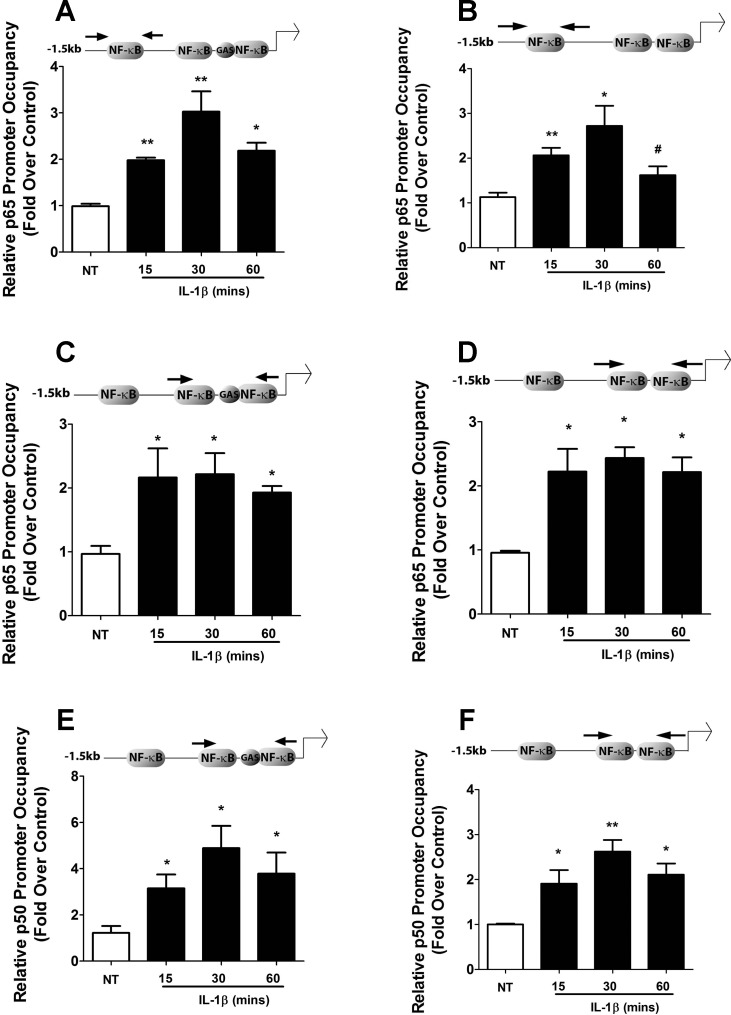

NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 are recruited to κB regulatory elements within the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters in an IL-1β-dependent manner.

Mutational analysis of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters, as well as siRNA-mediated suppression of the p65 and p50 subunits, revealed a role for NF-κB in the IL-1β-dependent upregulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes (Fig. 4). Thus, we next examined occupancy of the p65 and p50 subunits at conserved proximal and core promoter NF-κB binding sites, respectively, for each gene. We found a significant increase in p65 promoter occupancy at the common consensus κB site for both genes in response to IL-1β (Fig. 7, A and B). In addition, there was an enhancement in p65 association with κB sequences near the core promoter for both genes after exposure to IL-1β (Fig. 7, C and D). Moreover, there was an IL-1β-mediated increase in occupancy of p50 near the core promoters of both the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes (Figs. 7, E and F). Thus, IL-1β promotes association of key regulatory factors with the appropriate response elements driving transcription of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes.

Fig. 7.

Cytokines promote recruitment of p65 and p50 to specific genomic regions in the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters. A–F: 832/13 cells were untreated or stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 15, 30, and 60 min. ChIP assays were carried out using antibodies that immunoprecipitated p65 (A–D) and p50 (E, F). Distal (A, B) and proximal (C–F) NF-κB elements (indicated by arrows in the schematics) in CXCL1 (left) and CXCL2 (right) promoters were targeted for amplification by real-time PCR using recovered DNA as a template. **P < 0.01 vs. NT (A, B, F), *P < 0.05 vs NT (A–F); #P < 0.1 vs. NT (B). Data represent means ± SE from 4 individual experiments.

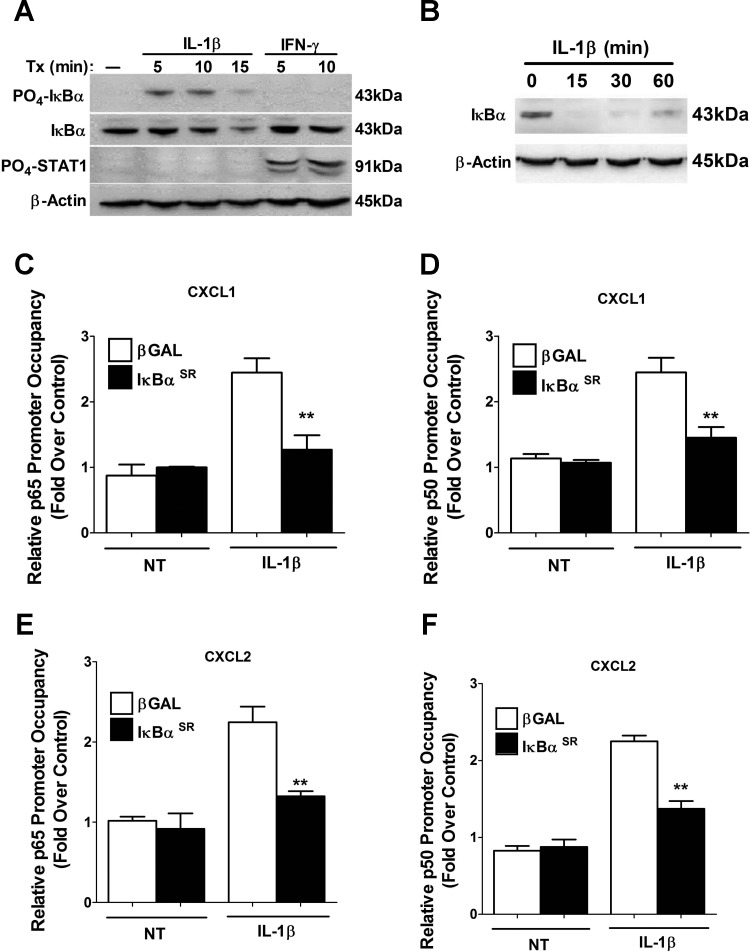

Consistent with the binding of NF-κB subunits to κB response elements, IL-1β signaling to IκBα is rapid, as we detected phosphorylation of the protein within 5 min of IL-1β exposure and observed degradation after 15 min of cytokine stimulus (Fig. 8A). The response is also stimulus specific, since IFNγ, which rapidly promotes phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701, does not induce phosphorylation or degradation of IκBα (Fig. 8A and data not shown). We next loaded 50% less protein to fully visualize IκBα degradation, at which point we observed full turnover of protein within 15 min with noticeable resynthesis detectable by 60 min (Fig. 8B). This observation fits with increased binding of p65 at gene promoters 15 and 30 min after exposure to IL-1β (Fig. 7).

Fig. 8.

NF-κB subunits are recruited to κB genomic response elements within the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters in a signal-dependent and IκBα-sensitive manner. A: 832/13 cells were stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 5, 10, and 15 min or 100 U/ml IFNγ for 5 and 10 min. Whole cell lysates (40 μg) were immunoblotted for PO4-IκBα, total IκBα, PO4-STAT1, and β-actin (as loading control). B: 832/13 cells were treated for 15, 30, and 60 min with 1 ng/ml IL-1β. Whole cell lysates (20 μg) were blotted for abundance of total IκBα with β-actin serving as loading control. C–F: 832/13 cells were cultured with recombinant adenoviruses that express either βGAL or IκBαSR for 12 h. Cells were then stimulated for 15 min with 1 ng/ml IL-1β. ChIP assays were performed with antibodies that immunoprecipitated p65 (C, E) and p50 (D, F). Proximal (C–F) NF-κB elements in the CXCL1 and CXCL2 core promoters were targeted for real-time PCR amplification. **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL + IL-1β. Data in C–F represent means ± SE from 3 individual experiments; immunoblots shown in A and B are representative of 2 independent experiments.

We next examined how overexpression of the IκBαSR protein impacted binding of p65 and p50 after an IL-1β stimulus. There was a 48.3% decrease in p65 occupancy at the core κB sites within the CXCL1 gene promoter in the presence of the adenoviral-delivered IκBαSR (Fig. 8C). Note that there was no change in the control condition, indicating stimulus-specific binding in response to IL-1β and a reduction by overexpression of the IκBαSR protein. There was also a 40.5% decrease in p50 association at the CXCL1 κB sequence in the presence of the IκBαSR protein (Fig. 8D). Binding of p65 and p50 at the CXCL2 gene promoter was also reduced by 41 and 39%, respectively, by overexpression of IκBαSR (Fig. 8, E and F). Thus, we conclude that signal-specific association of the NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 at precise gene promoter response elements matches the timing of degradation of IκBα.

STAT1 is an accessory factor for IL-1β-mediated expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes.

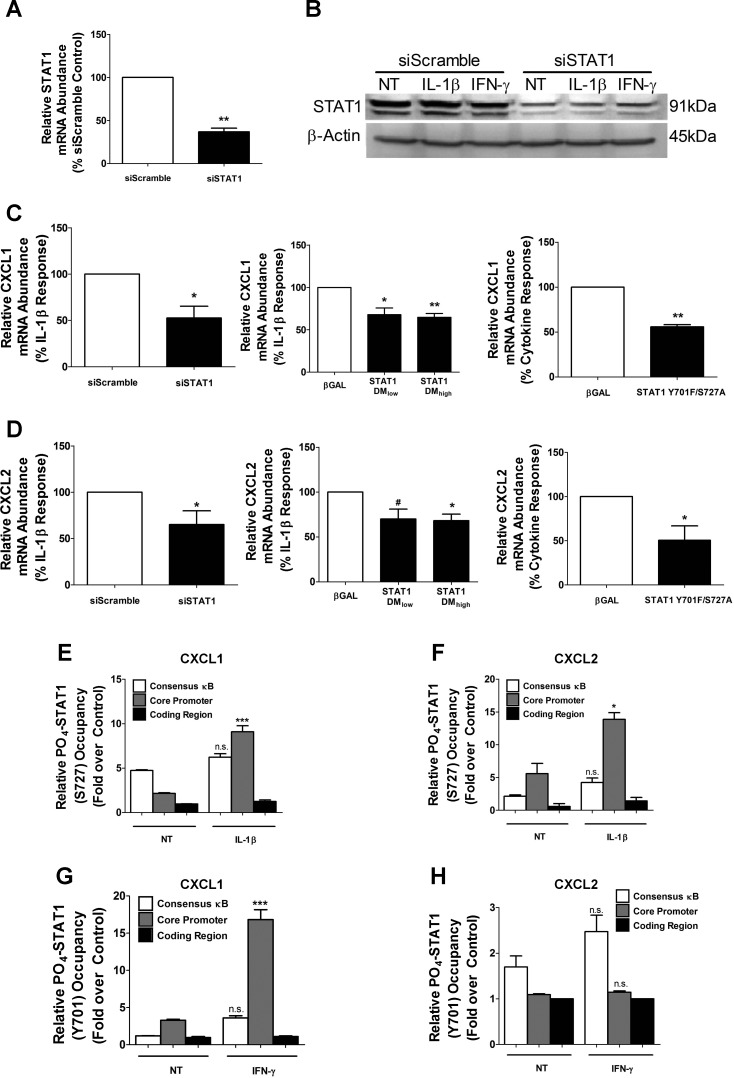

In addition to κB response elements, in silico analysis of the genomic regions upstream of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 coding regions reveal a number of sites potentially recognized by STAT1 (Table 2). Therefore, we used siRNA-directed suppression of STAT1 to determine whether the IL-1β response to either CXCL1 or CXCL2 was impacted. We detected a 63% decrease in STAT1 mRNA by siRNA duplex transfection (Fig. 9A), which produced a 50% decrease in STAT1 protein (Fig. 9B). The diminution in STAT1 reduced the ability of IL-1β to enhance transcript levels of both CXCL1 and CXCL2 (Fig. 9, C and D, left). We next examined whether specific phosphoacceptor sites at Tyr701 and Ser727, which are known to control STAT1 activity (77), interfered with the IL-1β response of each gene. Using adenoviral overexpression of STAT1 with Y701F/S727A mutations, we observed a decrease in the accumulation of CXCL1 and CXCL2 transcripts in 832/13 cells (Fig. 9, C and D, middle) and in isolated rat islets (Fig. 9, C and D, right).

Table 2.

Potential STAT1 binding sites within the rat CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters

| CXCL1 | CXCL2 | CXCL1/CXCL2 |

|---|---|---|

| TTTGCAGAA | TTCTGAGTA | −1445/−1289 |

| TTCAAGGAC | TTCTCTGTA | −887/−1258 |

| TTCAGGAA | TTTCCTGAA | −653/−732 |

| TTCTGGAA | TTCATGAA | −625/−723 |

| TCCAGCGAA | TTCCCGAA | −218/−665 |

| CTCCGGGAA* | TTCACAGAG | −87/−656 |

| ND | TTCCTCAAA | −317 |

| ND | TTCCCTGAT | −67 |

In silico examination of 1.5-kb regions controlling the proximal gene promoters for CXCL1 and CXCL2 reveals several regulatory sequences that are similar to a consensus γ-activated sequence (GAS) element. The putative STAT1 elements shown are either different by one nucleotide (nt) from a consensus GAS element or have a 2-nt spacer (NN) instead of a 3-nt spacer (NNN). One element in the CXCL1 gene promoter is a composite GAS/NF-κB sequence with demonstrated stimulus-induced STAT1 occupancy as shown in Fig. 9G.

Part of a Composite Element. Consensus GAS: TTCNNNGAA, where N is any nucleotide.

Fig. 9.

STAT1 is a key accessory factor for IL-1β-mediated gene transcription. A and B: 832/13 cells were transfected with an siRNA duplex targeting STAT1 or a scrambled sequence (siScramble) as a control. mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels of STAT1 were determined 48 h posttransfection. B: 832/13 cells were treated for 15 min with 1 ng/mL IL-1β or 100 U/ml IFNγ 48 h after siRNA transfection. Blots are from whole cell lysates with β-actin as loading control. C and D: 832/13 cells were transfected with an siSTAT1 duplex. Following 48 h incubation, cells were stimulated for 6 h with 1 ng/ml IL-1β (left). 832/13 cells were treated with adenoviruses expressing 2 increasing concentrations of STAT1 DM (double mutant; Y701F/S727A) for 24 h followed by 6 h stimulation with 1 ng/ml IL-1β (middle). Rat islets were transduced with adenoviruses expressing βGAL or STAT1 Y701F/S727A for 24 h and then treated for a further 6 h with 10 ng/ml IL-β and 100 U/ml IFNγ (right). CXCL1 (C) and CXCL2 (D) mRNA levels were measured. *P < 0.05 vs. siScramble (C, D), **P < 0.01 vs. siScramble (A); #P < 0.1 vs. βGAL (D); *P < 0.05 vs. βGAL (C, D), **P < 0.01 vs. βGAL (C). E and F: 832/13 cells were induced with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 15 min. ChIP assays were performed with antibodies that immunoprecipitate STAT1 PO4-S727 and IgG as negative control. G and H: 832/13 cells were stimulated for 15 min with 100 U/ml IFNγ. ChIP assays were employed to immunoprecipitate STAT1 PO4-Y701 with IgG as the negative control. Primer sets used for real-time PCR are indicated for CXCL1 (left) and CXCL2 (right). n.s. vs. respective control (E, F, G, H); *P < 0.05 vs. control (F), ***P < 0.001 vs. control (E, G). All experiments are expressed as means ± SE from 3–4 individual experiments. Immunoblot in B was performed on 2 separate occasions.

Using chromatin immunoprecipitation, we detected occupancy of phosphorylated STAT1Ser727 in the distal promoter region of the CXCL1 gene, which also contains the consensus κB response element (Fig. 9E, open bars). However, this STAT1Ser727 binding was not enhanced by the addition of IL-1β (Fig. 9E, open bars). By contrast, the binding of STAT1Ser727 near the core promoter is increased by 4.25-fold after IL-1β exposure (Fig. 9E, gray bars). We did not detect binding of STAT1 in the coding region of the CXCL1 gene, thus indicating stimulus-specific occupancy of this transcription factor within the proximal core promoter (Fig. 9E, filled bars).

Upon examining STAT1Ser727 occupancy at the CXCL2 gene, we observed a 2.49-fold increase at the region near the core promoter in response to IL-1β (Fig. 9F, gray bars). There was no discernible increase in STAT1Ser727 binding near the consensus κB site within the CXCL2 gene promoter (Fig. 9F, open bars) as well as no detectable binding in the coding region (Fig. 9F, filled bars). Because IFNγ promotes phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 in pancreatic β-cells (5, 8, 33), we specifically examined whether tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 was present at the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters. We found that IFNγ stimulates a 5.09-fold increase in STAT1Tyr701 occupancy at the core promoter region of the CXCL1 gene (Fig. 9G, gray bars). This fits with the CXCL1 core promoter containing a γ-activated sequence (GAS; Table 2). However, the increase in STAT1Tyr701 binding at this genomic regulatory site did not induce transcription of the gene or secretion of protein (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, A and B). By contrast, the CXCL2 gene, which does not contain a matching GAS element within its core promoter, did not result in STAT1Tyr701 occupancy in response to IFNγ at any regulatory regions examined (Fig. 9H). Thus, serine phosphorylated STAT1 serves as a potential accessory factor for the IL-1β-mediated increases in CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene transcription.

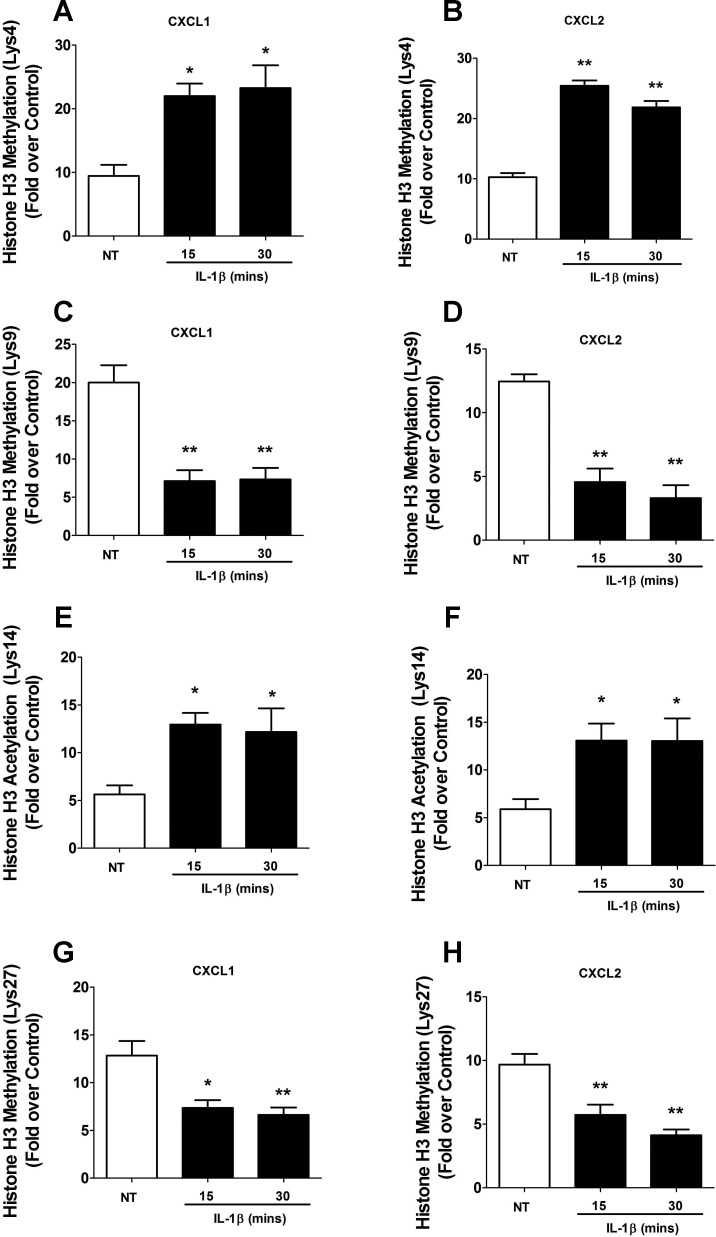

IL-1β promotes changes in histone modifications at regions associated with transcriptional regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes.

There are many alterations in chromatin that occur during transcription, including signal-induced changes in posttranslational modifications (43). Using ChIP assays, we found that IL-1β promotes changes in overall acetylation of histone H3 at both the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters (data not shown). Upon examining more precise sites of modification that correlate with regulation of gene transcription, we first found that methylation of H3K4 increased over twofold after exposure to IL-1β at both the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes (Fig. 10, A and B). Furthermore, methylation of H3K9 decreased 65 and 63%, respectively, after 15- or 30-min stimulus with IL-1β (Fig. 10C). There was similar 63 and 74% decreases in methylation of the H3K9 at the CXCL2 gene (Fig. 10D). Upon examining the acetylation of Lys14 of histone H3, we observed a more than twofold increase at both the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes after IL-1β exposure (Fig. 10, E and F). Additionally, methylation of histone H3 at Lys27 decreased by 43 and 48% at the CXCL1 gene (Fig. 10G), while methylation of this residue decreased by 41 and 57% at the CXCL2 gene (Fig. 10H). Note that all of those changes occurred in an IL-1β-dependent manner. We conclude that the regulation of CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene transcription by IL-1β is associated with key modifications to histones within the promoter regions of each of these genes.

Fig. 10.

IL-1β promotes specific changes in histone acetylation and methylation at regions associated with transcriptional regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes. A–H: 832/13 cells were untreated or stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 15 or 30 min. ChIP assays were performed using antibodies that immunoprecipitate methylated histone H3 (A, B: lysine 4; C, D: lysine 9; G, H: lysine 27) and acetylated histone H3 (E, F: lysine 14). The core promoter region of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes was amplified by real-time PCR. *P < 0.05 vs. NT, **P < 0.01 vs. NT. ChIP assays are represented as means ± SE from 4 individual experiments.

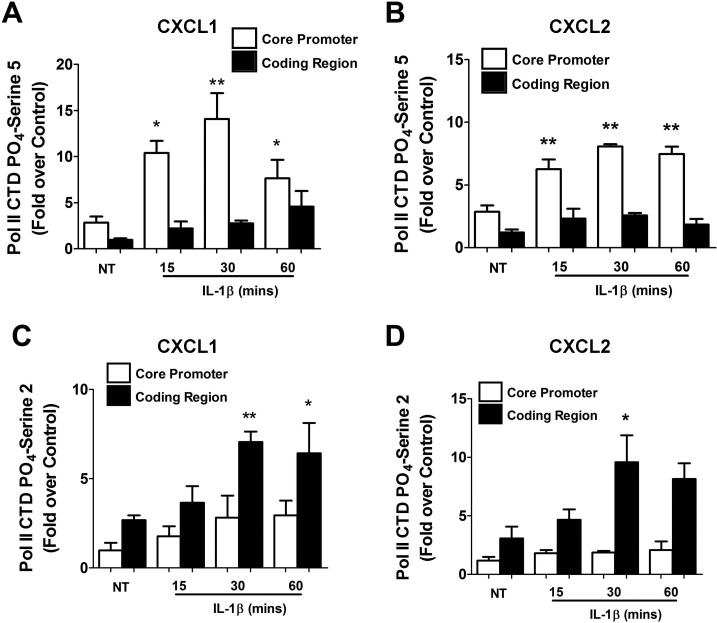

RNA polymerase II phosphorylation at the core promoter and coding regions of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes changes upon exposure to IL-1β.

Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) at the carboxy terminal domain (CTD) regulates both transcription and RNA processing (37). Because CXCL1 and CXCL2 are induced by IL-1β, we examined whether RNA Pol II phosphorylation status was changed concurrently. RNA Pol II phosphorylation at Ser5 increased 3.71-, 4.98-, and 2.70-fold at 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively, at the CXCL1 core promoter region (Fig. 11A). This timing is consistent with the first appearance of CXCL1 transcript upon exposure to IL-1β (Fig. 1). Similar results were obtained at the core promoter region in the CXCL2 gene (Fig. 11B). In addition, phosphorylation of Ser2, which is associated with elongation, increased 2.63- and 2.39-fold at 30 and 60 min, respectively, in the coding region of CXCL1 after IL-1β exposure (Fig. 11C). Within the CXCL2 coding region, we detected 3.11-fold and 2.65-fold increases in Ser2 phosphorylation, respectively, after a 30- or 60-min stimulus with IL-1β (Fig. 11D). Thus, phosphorylation of RNA Pol II is altered in response to IL-1β in a manner consistent with transcription factor binding, histone chemical modifications, and timing of gene transcription.

Fig. 11.

IL-1β induces signal-specific phosphorylation of RNA Pol II on the CXCL1 and CXCL2 promoters. A–D: 832/13 cells were untreated or stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 15, 30, or 60 min. ChIP assays using antisera to immunoprecipitate Pol II CTD PO4-serine 5 (A, B) or Pol II CTD PO4-serine 2 (C, D). The core promoter region and a segment of the coding region, downstream of the transcriptional start site, corresponding to CXCL1(left) and CXCL2 (right) genes were targeted for real-time PCR amplification. *P < 0.05 vs. NT, **P < 0.01 vs. NT. ChIP assays are expressed as means ± SE from 3–4 individual experiments.

DISCUSSION

The autoimmune-mediated elimination of pancreatic β-cells is a complex process that requires intricate interactions between diverse types of immune cells (46). While the initiating event in the organ-specific autoimmunity that leads to T1DM has not been identified, it is clear that chemokines are critical signals for immune cell recruitment into pancreatic islets (28, 50, 60). Chemokines are small secreted proteins (≈8–10 kDa) that are not typically stored in individual cells but rather are synthesized and secreted in response to a specific stimulus. In this study, we examined the transcriptional control of two chemokine genes, CXCL1 and CXCL2, in response to IL-1β in pancreatic β-cells.

IL-1β is one of the principal cytokines involved in β-cell death and dysfunction during development of T1DM (47, 57) and is a key contributor to onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM; (23, 30)]. The chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 are synthesized and secreted in response to IL-1β in pancreatic β-cells (Figs. 1 and 2 and Ref. 18). Serum CXCL1 levels are also higher in individuals with T1DM (71) and T2DM (64). Moreover, a recent systems biology study showed an association of both CXCL1 and CXCL2 with various autoimmune diseases, including T1DM (72). Thus, transcriptional regulation of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes by IL-1β is likely to represent a key critical component underlying β-cell inflammation.

Chromatin remodeling is one of the central events associated with transcriptional regulation. There are many posttranslational modifications to histone proteins that either alter the milieu of regulatory factors promoting the transcriptional activation or repression of specific genes and/or that provide docking sites for additional proteins participating in the regulatory process (43). To our knowledge, our results are the first to demonstrate histone chemical modifications at the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters in response to IL-1β in the pancreatic β-cell. Indeed, sites associated with transcriptional activation, such as methylation at H3K4, increased with IL-1β exposure (Fig. 10, A and B), while sites associated with transcriptional repression, such as methylation at H3K9, decreased with IL-1β exposure (Fig. 10, C and D). Overall, the histone chemical modifications detected at the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes are consistent with signal-specific activation of gene transcription by IL-1β. These data provide heretofore undescribed regulatory information regarding control of these key chemokine genes under inflammatory conditions in pancreatic β-cells.

CXCL1 and CXCL2 are capable of attracting CXCR2+ cells, such as neutrophils, to sites of inflammation (63). Neutrophils participate in the initiation of the autoimmune-mediated process that results in a decrease in functional β-cell mass (22). However, how different leukocytes collaborate to initiate the autoimmune process is not well understood. Initiation of autoimmunity and/or continuation of the autoinflammatory response that leads to β-cell destruction may require the synthesis and secretion of chemokines, such as CXCL1 and CXCL2, directly from the islet β-cells. These chemoattractant proteins recruit cells that begin (or maintain) the inflammatory process, eventually leading to the onset and progression of autoimmunity (22, 46). Indeed, both rodent and human β-cells make and secrete CXCL1 and CXCL2 (see Refs. 18 and 65 and Figs. 1 and 2 of this study), which bind to CXCR2 to initiate neutrophil activation and migration (Ref. 55 and data not shown). Although very effective against recombinant CXCL1 alone, the allosteric inhibitor of CXCR2 does not entirely block the migratory response to β-cell supernatants (Fig. 2E). We interpret these data to indicate that there may be additional chemokines capable of activating or recruiting neutrophils independently of CXCR2.

Neutrophils are involved in initiating autoimmune-mediated β-cell destruction (22, 46), and β-cells are killed in response to proinflammatory cytokine exposure (11, 12, 27, 70). Islet β-cell death occurs with release of the damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules, such as HMGB1 (70). We posit that release of HMGB1 (and potentially other DAMPs) triggers neutrophil activation and recruitment of additional immune cells to the site of dead and dying β-cells. The amalgamation of chemokines secreted from inflamed tissue (e.g., islets exposed to IL-1β) in combination with DAMPs, such as HMGB1, may synergize to enhance leukocyte chemoattraction in addition to effects on immune cell function (66, 81). Because of the many diverse leukocyte populations that participate in autoimmune-mediated β-cell destruction (46, 57), there may be additive or synergistic effects between multiple chemokines and/or DAMPs on immune cell recruitment, activation, and release of cytotoxic molecules. Along these lines, viral chemokines increase cell surface expression of CD11b and CD11c on PBNs, which in turn can affect downstream activation signals (52). CXCL8 increases the expression of integrins, including CD11b/CD18, on PBNs (20). Herein, we report that exposure to either CXCL1 or CXCL2 alone (Fig. 2C) increased CD11b and CD11c expression in human PBNs without altering CD11a expression, whereas the combination of these chemokines was redundant (Fig. 2D) Thus, there are no additional combinatorial or priming effects of CXCL1/CXCL2 on integrin expression at the concentrations tested in this study.

The evidence for the importance of CXCL1 and CXCL2 in diabetes continues to grow. For example, there is a mild decrease in circulating PBNs that precedes the onset of T1DM (74). Although this initially seems to contradict the role of neutrophils in T1DM, the authors also reported an increase in neutrophils in the pancreas. An explanation for the loss of PBNs in circulation is that they extravasated from the bloodstream into the pancreas in response to elevated synthesis and secretion of chemoattractants such as CXCL1 and CXCL2. In T2DM, the associated lipid overload induces tissue dysfunction and promotes M1 macrophage activation in pancreatic islets (25, 73); the expression of the CXCL1 and CCL2 genes is linked to this phenotype (25). In addition, CXCL1 and CCL2 expression is increased in the islets of genetic models of obesity and diabetes such as the db/db mouse (25). Thus, islet inflammation, a key factor associated with losses in functional β-cell mass in both T1DM and T2DM (24, 26, 57) may be initiated and/or exacerbated by locally high chemokine gene expression and secretion (e.g., such as within pancreatic islets). Expression of these chemokines is driven largely by activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in response to IL-1β (Refs. 5, 7, and 57 and the present study). This may explain why sequestering IL-1β, using cytokine trap strategies, promotes improvements in β-cell function (75) and survival of transplanted islets (62) but does not ameliorate peripheral insulin resistance (75).

One commonality between all the chemokine genes induced by IL-1β in the pancreatic β-cell studied thus far is their regulation by NF-κB proteins, in which the p65 subunit plays a critical role. Indeed, a key finding in the present study is that the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes both have a consensus NF-κB response element within their proximal gene promoters, at an almost identical genomic positioning (Table 1). p65/RelA, one of the major transcriptional activators of the NF-κB family of proteins, occupies these sites in response to IL-1β (Fig. 7, A and B). Additional κB sequences are also present in the promoters of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes, including near the transcriptional start site (Table 1). Thus, the data presented in this study provide molecular evidence supporting the systems biology approach that indicated a strong link between IL-1/NF-κB and CXCL1/2 in autoimmune diseases (72). Our data also explain why small molecule inhibition of the CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors prolongs the survival of transplanted pancreatic islets (10).

An additional novel observation in our study was the identification of serine-phosphorylated STAT1 as a key accessory factor for the IL-1β-mediated transcriptional induction of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes (Fig. 9). Altough IFNγ can promote STAT1 phosphorylation at Tyr701 (Fig. 8A) and association with genomic regions of these genes (Fig. 9), it does not promote synthesis of transcript (Fig. 1) or secretion of chemokine proteins (Fig. 2, A and B). IL-1β promotes p65 association with the CXCL1 and CXCL2 gene promoters (Figs. 7 and 8), which induces robust transcript production (Fig. 1) and secretion of chemokine protein (Fig. 2, A and B). We speculate that preloading of STAT1 phosphorylated at Ser727 onto genomic regions in the proximal gene promoters might serve to prime the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes for the major stimulus that enhances transcription (e.g., IL-1β). In support of this notion, we discovered that there are several “GAS-like” sites distributed throughout the proximal promoters of these two chemokine genes (Table 2). We speculate that, although each of these sites individually may be relatively low-affinity binding sites (compared with a consensus GAS), they collectively provide support for STAT1 occupancy prior to an IL-1β stimulus.

IL-1β increases transcription in a time frame that is congruent with alterations in histone chemical modifications (Fig. 10) and Pol II phosphorylation at both the core promoter and coding regions (Fig. 11). Furthermore, our results using STAT1 deletion or removal of phosphoacceptor sites reveal a decrease in the ability of pancreatic β-cells to induce chemokine gene transcription (Fig. 9). These observations provide a novel molecular explanation for a prior study showing that STAT1 deletion prevents insulitis in NOD mice (41). Accordingly, interfering with STAT1 abundance or activity diminishes production of the chemoattractant signals that promote immune cell invasion into islets. In addition, diminishing STAT1 activity also impacts the IL-1β-mediated expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene (8). The expression of iNOS and subsequent production of NO is strongly associated with losses in functional β-cell mass (15–17, 70). Thus, STAT1 is a major contributor to the β-cell inflammation that is associated with islet β-cell destruction.

Overall, chemokines impact a variety of human diseases (39, 76). Therefore, a full understanding of the transcriptional processes controlling their expression is critical for development of novel therapeutic approaches to treat or prevent many human diseases, including diabetes and cancer. For example, the inflammatory responses induced by chemotherapeutic drugs also promote NF-κB activation, which in turn activates chemokine gene transcription (44, 61). Along these lines, increased expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in breast cancer cells promotes tumor survival in metastatic regions (1). Interference with CXCR2 signaling enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy, implicating CXCR2 in metastasis and demonstrating another key role for chemokines in human disease. In addition, CXCL1 and CXCL2 are elevated in tumorigenic melanocytes, allowing these cells to form tumors in immune-compromised mice (79); normal melanocytes do not express these chemokines (21, 80).

Finally, we also demonstrated herein that IκKβ plays a key role in regulating the expression of the CXCL1 and CXCL2 genes in β-cells (Figs. 5 and 6), matching the NF-κB-driven expression of chemokines in human melanoma cells (80). TNF-α, IL-1β, or other inflammatory stimuli capable of activating IκKβ, would thus have the potential to drive CXCL1 and CXCL2 expression in a variety of tissues. This finding has major implications for both autoimmune diseases and the upregulation of NF-κB-responsive genes after chemotherapeutic treatments in specific cancers. It therefore establishes IκKβ as an attractive target with broad therapeutic potential. Furthermore, a combination therapy of CXCR2 interference with discrete approaches that dampen NF-κB activation (e.g., IκKβ inhibition) may be one way to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of existing treatments and/or to circumvent side effects caused by high doses of individual salutary approaches. Still more appealing may be the targeting of specific transcription factor complexes or enhanceosomes, which would allow for cell-specific, signal-specific, and perhaps even gene-specific therapeutic interventions. Such approaches await full characterization of the transcriptional mechanisms controlling precise regulatory networks involved in inflammatory processes.

GRANTS

Support for this work was through start-up funds provided by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (to J. J. Collier), a grant from the Physicians' Medical Education and Research Foundation (to M. D. Karlstad and J. J. Collier), funding from the Microbiology across Campuses Educational and Research Venture (to J. J. Collier and T. E. Sparer), and NIH Grant RO1 AI-071042 (to T. E. Sparer).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.J.B. and J.J.C. conception and design of research; S.J.B., D.L., T.E.S., T.M., and M.R.G. performed experiments; S.J.B., D.L., T.E.S., T.M., and J.J.C. analyzed data; S.J.B., T.E.S., T.M., M.D.K., and J.J.C. interpreted results of experiments; S.J.B., T.E.S., T.M., M.R.G., and J.J.C. prepared figures; S.J.B. and J.J.C. drafted manuscript; S.J.B., T.E.S., M.R.G., M.D.K., and J.J.C. edited and revised manuscript; S.J.B., D.L., T.E.S., T.M., M.R.G., M.D.K., and J.J.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Naima Moustaid-Moussa, Chris Newgard, Jay Whelan, and Haiyan Xu for reagents. We also express our gratitude to Emily Lazek and Dana Omari for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acharyya S, Oskarsson T, Vanharanta S, Malladi S, Kim J, Morris PG, Manova-Todorova K, Leversha M, Hogg N, Seshan VE, Norton L, Brogi E, Massague J. A CXCL1 paracrine network links cancer chemoresistance and metastasis. Cell 150: 165–178, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, Metzler KD, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 459–489, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M. Chemokines in pathology and medicine. J Intern Med 250: 91–104, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke SJ, Collier JJ. The gene encoding cyclooxygenase-2 is regulated by IL-1beta and prostaglandins in 832/13 rat insulinoma cells. Cell Immunol 271: 379–384, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke SJ, Goff MR, Lu D, Proud D, Karlstad MD, Collier JJ. Synergistic expression of the CXCL10 gene in response to IL-1beta and IFN-gamma involves NF-kappaB, phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701, and acetylation of histones H3 and H4. J Immunol 191: 323–336, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke SJ, Goff MR, Updegraff BL, Lu D, Brown PL, Minkin SC, Jr, Biggerstaff JP, Zhao L, Karlstad MD, Collier JJ. Regulation of the CCL2 gene in pancreatic beta-cells by IL-1beta and glucocorticoids: role of MKP-1. PLoS One 7: e46986, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke SJ, Updegraff BL, Bellich RM, Goff MR, Lu D, Minkin SC, Jr, Karlstad MD, Collier JJ. Regulation of iNOS gene transcription by IL-1beta and IFN-gamma requires a coactivator exchange mechanism. Mol Endocrinol 27: 1724–1742, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderon B, Suri A, Unanue ER. In CD4+ T-cell-induced diabetes, macrophages are the final effector cells that mediate islet beta-cell killing: studies from an acute model. Am J Pathol 169: 2137–2147, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Citro A, Cantarelli E, Maffi P, Nano R, Melzi R, Mercalli A, Dugnani E, Sordi V, Magistretti P, Daffonchio L, Ruffini PA, Allegretti M, Secchi A, Bonifacio E, Piemonti L. CXCR1/2 inhibition enhances pancreatic islet survival after transplantation. J Clin Invest 122: 3647–3651, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collier JJ, Burke SJ, Eisenhauer ME, Lu D, Sapp RC, Frydman CJ, Campagna SR. Pancreatic beta-cell death in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines is distinct from genuine apoptosis. PLoS One 6: e22485, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collier JJ, Fueger PT, Hohmeier HE, Newgard CB. Pro- and antiapoptotic proteins regulate apoptosis but do not protect against cytokine-mediated cytotoxicity in rat islets and beta-cell lines. Diabetes 55: 1398–1406, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coppieters KT, Dotta F, Amirian N, Campbell PD, Kay TW, Atkinson MA, Roep BO, von Herrath MG. Demonstration of islet-autoreactive CD8 T cells in insulitic lesions from recent onset and long-term type 1 diabetes patients. J Exp Med 209: 51–60, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coppieters KT, von Herrath MG. Histopathology of type 1 diabetes: old paradigms and new insights. Rev Diabet Stud 6: 85–96, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbett JA, Mikhael A, Shimizu J, Frederick K, Misko TP, McDaniel ML, Kanagawa O, Unanue ER. Nitric oxide production in islets from nonobese diabetic mice: aminoguanidine-sensitive and -resistant stages in the immunological diabetic process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 8992–8995, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbett JA, Sweetland MA, Wang JL, Lancaster JR, Jr, McDaniel ML. Nitric oxide mediates cytokine-induced inhibition of insulin secretion by human islets of Langerhans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 1731–1735, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbett JA, Wang JL, Misko TP, Zhao W, Hickey WF, McDaniel ML. Nitric oxide mediates IL-1 beta-induced islet dysfunction and destruction: prevention by dexamethasone. Autoimmunity 15: 145–153, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowley MJ, Weinberg A, Zammit NW, Walters SN, Hawthorne WJ, Loudovaris T, Thomas H, Kay T, Gunton JE, Alexander SI, Kaplan W, Chapman J, O'Connell PJ, Grey ST. Human islets express a marked proinflammatory molecular signature prior to transplantation. Cell Transplant 21: 2063–2078, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IkappaB kinase activity through IKKbeta subunit phosphorylation. Science 284: 309–313, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Detmers PA, Lo SK, Olsen-Egbert E, Walz A, Baggiolini M, Cohn ZA. Neutrophil-activating protein 1/interleukin 8 stimulates the binding activity of the leukocyte adhesion receptor CD11b/CD18 on human neutrophils. J Exp Med 171: 1155–1162, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhawan P, Richmond A. A novel NF-kappa B-inducing kinase-MAPK signaling pathway up-regulates NF-kappa B activity in melanoma cells. J Biol Chem 277: 7920–7928, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diana J, Simoni Y, Furio L, Beaudoin L, Agerberth B, Barrat F, Lehuen A. Crosstalk between neutrophils, B-1a cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells initiates autoimmune diabetes. Nat Med 19: 65–73, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinarello CA, Donath MY, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Role of IL-1beta in type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 17: 314–321, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 98–107, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eguchi K, Manabe I, Oishi-Tanaka Y, Ohsugi M, Kono N, Ogata F, Yagi N, Ohto U, Kimoto M, Miyake K, Tobe K, Arai H, Kadowaki T, Nagai R. Saturated fatty acid and TLR signaling link beta cell dysfunction and islet inflammation. Cell Metab 15: 518–533, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehses JA, Perren A, Eppler E, Ribaux P, Pospisilik JA, Maor-Cahn R, Gueripel X, Ellingsgaard H, Schneider MK, Biollaz G, Fontana A, Reinecke M, Homo-Delarche F, Donath MY. Increased number of islet-associated macrophages in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 56: 2356–2370, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fehsel K, Kolb-Bachofen V, Kroncke KD. Necrosis is the predominant type of islet cell death during development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in BB rats. Lab Invest 83: 549–559, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frigerio S, Junt T, Lu B, Gerard C, Zumsteg U, Hollander GA, Piali L. Beta cells are responsible for CXCR3-mediated T-cell infiltration in insulitis. Nat Med 8: 1414–1420, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gepts W. Pathologic anatomy of the pancreas in juvenile diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 14: 619–633, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant RW, Dixit VD. Mechanisms of disease: inflammasome activation and the development of type 2 diabetes. Front Immunol 4: 50, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, the first quarter-century: remarkable progress and outstanding questions. Genes Dev 26: 203–234, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell 132: 344–362, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heitmeier MR, Scarim AL, Corbett JA. Interferon-gamma increases the sensitivity of islets of Langerhans for inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression induced by interleukin 1. J Biol Chem 272: 13697–13704, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herder C, Baumert J, Thorand B, Koenig W, de Jager W, Meisinger C, Illig T, Martin S, Kolb H. Chemokines as risk factors for type 2 diabetes: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg study, 1984–2002. Diabetologia 49: 921–929, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herz J, Gerard RD. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of low density lipoprotein receptor gene acutely accelerates cholesterol clearance in normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 2812–2816, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 49: 424–430, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsin JP, Manley JL. The RNA polymerase II CTD coordinates transcription and RNA processing. Genes Dev 26: 2119–2137, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Israel A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a000158, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin T, Xu X, Hereld D. Chemotaxis, chemokine receptors and human disease. Cytokine 44: 1–8, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jobin C, Panja A, Hellerbrand C, Iimuro Y, Didonato J, Brenner DA, Sartor RB. Inhibition of proinflammatory molecule production by adenovirus-mediated expression of a nuclear factor kappaB super-repressor in human intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol 160: 410–418, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, Kim HS, Chung KW, Oh SH, Yun JW, Im SH, Lee MK, Kim KW, Lee MS. Essential role for signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 in pancreatic beta-cell death and autoimmune type 1 diabetes of nonobese diabetic mice. Diabetes 56: 2561–2568, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knip M, Siljander H. Autoimmune mechanisms in type 1 diabetes. Autoimmun Rev 7: 550–557, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128: 693–705, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazennec G, Richmond A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol Med 16: 133–144, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LeCompte PM, Legg MA. Insulitis (lymphocytic infiltration of pancreatic islets) in late-onset diabetes. Diabetes 21: 762–769, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehuen A, Diana J, Zaccone P, Cooke A. Immune cell crosstalk in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 501–513, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandrup-Poulsen T. The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of IDDM. Diabetologia 39: 1005–1029, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markert M, Andrews PC, Babior BM. Measurement of O2- production by human neutrophils. The preparation and assay of NADPH oxidase-containing particles from human neutrophils. Methods Enzymol 105: 358–365, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marrack P, Kappler J, Kotzin BL. Autoimmune disease: why and where it occurs. Nat Med 7: 899–905, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin AP, Rankin S, Pitchford S, Charo IF, Furtado GC, Lira SA. Increased expression of CCL2 in insulin-producing cells of transgenic mice promotes mobilization of myeloid cells from the bone marrow, marked insulitis, and diabetes. Diabetes 57: 3025–3033, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Li J, Young DB, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science 278: 860–866, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller-Kittrell M, Sai J, Penfold M, Richmond A, Sparer TE. Functional characterization of chimpanzee cytomegalovirus chemokine, vCXCL-1(CCMV). Virology 364: 454–465, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 173–182, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nemeth T, Mocsai A. The role of neutrophils in autoimmune diseases. Immunol Lett 143: 9–19, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Callaghan K, Kuliopulos A, Covic L. Turning receptors on and off with intracellular pepducins: new insights into G-protein-coupled receptor drug development. J Biol Chem 287: 12787–12796, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol 12: 695–708, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Padgett LE, Broniowska KA, Hansen PA, Corbett JA, Tse HM. The role of reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines in type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1281: 16–35, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park G, Masi T, Choi CK, Kim H, Becker JM, Sparer TE. Screening for novel constitutively active CXCR2 mutants and their cellular effects. Methods Enzymol 485: 481–497, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Podolin PL, Callahan JF, Bolognese BJ, Li YH, Carlson K, Davis TG, Mellor GW, Evans C, Roshak AK. Attenuation of murine collagen-induced arthritis by a novel, potent, selective small molecule inhibitor of IkappaB kinase 2, TPCA-1 (2-[(aminocarbonyl)amino]-5-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-thiophenecarboxamide), occurs via reduction of proinflammatory cytokines and antigen-induced T cell Proliferation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312: 373–381, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhode A, Pauza ME, Barral AM, Rodrigo E, Oldstone MB, von Herrath MG, Christen U. Islet-specific expression of CXCL10 causes spontaneous islet infiltration and accelerates diabetes development. J Immunol 175: 3516–3524, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richmond A. Nf-kappa B, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth. Nat Rev Immunol 2: 664–674, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rydgren T, Oster E, Sandberg M, Sandler S. Administration of IL-1 trap prolongs survival of transplanted pancreatic islets to type 1 diabetic NOD mice. Cytokine 63: 123–129, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sadik CD, Kim ND, Luster AD. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends Immunol 32: 452–460, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sajadi SM, Khoramdelazad H, Hassanshahi G, Rafatpanah H, Hosseini J, Mahmoodi M, Arababadi MK, Derakhshan R, Hasheminasabzavareh R, Hosseini-Zijoud SM, Ahmadi Z. Plasma levels of CXCL1 (GRO-alpha) and CXCL10 (IP-10) are elevated in type 2 diabetic patients: evidence for the involvement of inflammation and angiogenesis/angiostasis in this disease state. Clin Lab 59: 133–137, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sarkar SA, Lee CE, Victorino F, Nguyen TT, Walters JA, Burrack A, Eberlein J, Hildemann SK, Homann D. Expression and regulation of chemokines in murine and human type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 61: 436–446, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418: 191–195, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shimada A, Morimoto J, Kodama K, Suzuki R, Oikawa Y, Funae O, Kasuga A, Saruta T, Narumi S. Elevated serum IP-10 levels observed in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 24: 510–515, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smale ST. Hierarchies of NF-kappaB target-gene regulation. Nat Immunol 12: 689–694, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steer SA, Scarim AL, Chambers KT, Corbett JA. Interleukin-1 stimulates beta-cell necrosis and release of the immunological adjuvant HMGB1. PLoS Med 3: e17, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi K, Ohara M, Sasai T, Homma H, Nagasawa K, Takahashi T, Yamashina M, Ishii M, Fujiwara F, Kajiwara T, Taneichi H, Takebe N, Satoh J. Serum CXCL1 concentrations are elevated in type 1 diabetes mellitus, possibly reflecting activity of anti-islet autoimmune activity. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 27: 830–833, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tuller T, Atar S, Ruppin E, Gurevich M, Achiron A. Common and specific signatures of gene expression and protein-protein interactions in autoimmune diseases. Genes Immun 14: 67–82, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Unger RH. Lipotoxic diseases. Annu Rev Med 53: 319–336, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Valle A, Giamporcaro GM, Scavini M, Stabilini A, Grogan P, Bianconi E, Sebastiani G, Masini M, Maugeri N, Porretti L, Bonfanti R, Meschi F, De Pellegrin M, Lesma A, Rossini S, Piemonti L, Marchetti P, Dotta F, Bosi E, Battaglia M. Reduction of circulating neutrophils precedes and accompanies type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 62: 2072–2077, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Asseldonk EJ, Stienstra R, Koenen TB, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Tack CJ. Treatment with Anakinra improves disposition index but not insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic subjects with the metabolic syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: 2119–2126, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Viola A, Luster AD. Chemokines and their receptors: drug targets in immunity and inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 48: 171–197, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE., Jr Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell 82: 241–250, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams MA, Solomkin JS. Integrin-mediated signaling in human neutrophil functioning. J Leukoc Biol 65: 725–736, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang J, Luan J, Yu Y, Li C, DePinho RA, Chin L, Richmond A. Induction of melanoma in murine macrophage inflammatory protein 2 transgenic mice heterozygous for inhibitor of kinase/alternate reading frame. Cancer Res 61: 8150–8157, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang J, Richmond A. Constitutive IkappaB kinase activity correlates with nuclear factor-kappaB activation in human melanoma cells. Cancer Res 61: 4901–4909, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu M, Wang H, Ding A, Golenbock DT, Latz E, Czura CJ, Fenton MJ, Tracey KJ, Yang H. HMGB1 signals through toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock 26: 174–179, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]