Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor-19 (FGF-19), a bile acid-responsive enterokine, is secreted by the ileum and regulates a variety of metabolic processes. These studies examined the signal transduction pathways operant in FGF-19-mediated repression of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT). Responses to FGF-19 were assessed in Caco-2 and CT-26 cells and in mice where c-fos was conditionally silenced in the intestine by a cre-lox strategy. FGF-19 treatment of Caco-2 cells or wild-type mice led to a significant reduction in ASBT protein expression and enhanced phosphorylation of extracellular signaling kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), c-Fos, and c-Jun. FGF-19 treatment of Caco-2 cells led to a reduction in activity of the human ASBT promoter and this repression could be blocked by treatment with a mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase (MEK1/2) inhibitor or by silencing jun kinase 1, jun kinase 2, c-fos, or c-jun. Site directed mutagenesis of a c-fos binding element in the ASBT promoter blocked FGF-19-mediated repression in luciferase reporter constructs. ASBT promoter activity was repressed by FGF-19 in CT-26 cells and this repression could be reduced by MEK1/2 inhibition or silencing c-fos. FGF-19-mediated repression of ASBT protein expression was abrogated in mice where c-fos was conditionally silenced in the intestine. In contrast, ASBT was repressed in the c-Fos expressing gallbladders of the same mice. The studies demonstrate that FGF-19 represses the expression of ASBT in the ileum and gallbladder via a signal transduction pathway involving MEK1/2, ERK1/2, JNK1, JNK2, and c-Fos.

Keywords: gallbladder, ileum, intestine, signal transduction

the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter, ASBT (slc10a2), plays a critical role in the enterohepatic circulation of bile salts (13). ASBT mediates sodium-dependent bile acid transport in ileal enterocytes, renal proximal convoluted tubule cells, and cholangiocytes. ASBT expression is relevant for bile acid, cholesterol, glucose, and lipid homeostasis (12). Genetic defects in ASBT expression are associated with congenital diarrhea, which can be mimicked in a mouse knockout model (14, 41). Pharmacological inhibition of its function leads to intestinal wasting of bile acid and commensurate conversion of cholesterol into bile acids with a significant impact on cholesterol homeostasis (22, 42). Inhibition of ASBT function can also ameliorate hyperglycemia in a mouse model (8). Ileal ASBT expression is reduced in patients with hypertriglyceridemia (15). Alterations in ASBT expression may influence a variety of disease processes and conditions including diarrhea, cholestasis, and necrotizing enterocolitis. ASBT is repressed in the setting of intestinal inflammation, which may exacerbate diarrheal symptoms in Crohn disease (28). Maladaptive upregulation of ASBT expression may be a generalized problem in cholestasis and a more specific pathogenesis of the cholestasis associated with defects in the ATP8B1 gene (Byler disease) (2, 23). Necrotizing enterocolitis in a mouse model is attenuated when ASBT is inhibited or genetically deleted (21). In light of the findings, ASBT has become an interesting target for new pharmacological therapies including treatment of constipation, primary biliary cirrhosis, and Alagille syndrome (10) (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ last accessed 09.28.13).

Given its importance in health and disease, the expression of ASBT is tightly controlled at varied levels including transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation. ASBT has been shown to be transcriptionally activated by the HNF-1a, c-Jun, the glucocorticoid receptor, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, the vitamin D receptor and the caudal-type homeobox protein (4, 9, 28, 29, 35, 45). ASBT expression is regulated posttranscriptionally including changes in ASBT mRNA stability mediated by the RNA binding proteins Hu antigen R and tristetraprolin (7). ASBT targeting to the plasma membrane is reduced by activation of protein kinase c zeta (44). The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway mediates regulated degradation of ASBT (52). ASBT has been recently described as a regulatory target of the enterokine, fibroblast growth factor-19 (FGF-19) (47).

FGF-19 (mouse ortholog FGF-15) is an atypical member of the family of FGFs, which were initially characterized by their ability to stimulate fibroblast proliferation through FGF receptors (27). FGF-19 is not tightly bound by extracellular matrix and thus can act as an endocrine, paracrine, or autocrine factor. FGF-19 is synthesized in enterocytes and cholangiocytes and mediates its effects through the cell surface proteins FGFR4 and β-Klotho (26, 54). Ileal FGF-19 regulates hepatocyte-based bile acid metabolism (25). A wide spectrum of targets and homeostatic processes have been discovered to be influenced by FGF-19 (31). β-Klotho knockout mice have enhanced hepatic bile acid secretion, yet unlike canalicular bile acid transporter-overexpressing mice, commensurate downregulation of ASBT expression in response to the enhanced delivery of bile acids to the ileum is not observed (18, 26). This suggests that FGF-19 is a physiological regulator of ASBT expression. FGF-19 transcription is activated by bile acids via the farnesoid X-receptor (FXR). As an autocrine factor, FGF-19 may repress ASBT expression, providing an immediate feedback loop controlling bile acid pool size. Enhanced delivery of bile acids to the ileum increases FGF-19, which through an autocrine loop represses ASBT, leading to intestinal wasting of bile acids.

ASBT expression is negatively regulated by a number of mechanisms. One pathway involves FXR-mediated activation of the short heterodimer partner and subsequent inactivation of the liver receptor homolog-1 (retinoic acid receptor in humans) (5, 39). Since the liver receptor homolog-1 is an activator of ASBT, the net effect is an indirect negative feedback regulation of ASBT by bile acids. A second inhibitory pathway involves the activator protein-1 (AP-1), c-Fos. This pathway is active in mediating response to inflammatory cytokines. The ASBT promoter contains two distinct AP-1 binding sites. The upstream site, uAP-1, binds a c-Jun homodimer that activates the promoter. In contrast, the downstream site, dAP-1, binds a c-Fos/c-Jun heterodimer leading to repression of ASBT transcription (6). FGF proteins activate immediate early response genes, like AP-1 (34). We therefore hypothesized that FGF-19 represses ASBT expression via a signaling pathway involving c-Fos.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Human Caco-2 colon epithelial cells (HTB-37, ATCC) were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Mouse CT-26 cells (CRL-2638, ATCC) were grown in RPMI medium with 10% FBS. Caco-2 cells were chosen for these studies because of their ability to provide accurate in vitro modeling of signal transduction pathways involved in bile acid transporter homeostasis and in response to inflammatory cytokines (16, 38, 44, 46, 47). CT-26 cells were chose as a mouse intestine cell line that recapitulates relevant signal transduction pathways (20). Cells treated with PD98059 (Calbiochem, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), U0126 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), or recombinant human FGF-19 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), were supplemented with 0.5% charcoal-treated FBS, minimizing the effect of bile acids found in FBS (19). Plasmid transfected cells were cultured for 48 h before harvest for reporter gene assays.

Plasmid Constructs

The following constructs were used in these studies.

pGL3-hASBT5′/0.6 (ASBT) and pGL3-hASBT5′/0.6-dAP1μ [dAP1ASBT(mut)].

pGL3-hASBT/0.6 contains nucleotides −337 to +297 of the human ASBT 5′ flanking region linked to a firefly luciferase reporter gene (38). pGL3-hASBT5′/0.6-dAP1μ contains a mutation in dAP-1 that blocks response to c-Fos (38). The c-fos-containing (pCMV/c-fos) was a generous gift from Dr. Scott Plevy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC (4, 6).

SV40/dAP1 and SV40/ZErO.

SV40/dAP1 contains a dAP-1 45-bp fragment downstream of the SV40 promoter in the luciferase reporter plasmid, pGL3-promoter (6). The control plasmid, SV40/ZErO, contains a nonspecific sequence in the same site (6).

Silencing RNAs.

Silencing RNAs for c-fos (sc-29221), c-jun (sc-29223), JNK1 (sc-29380), and JNK2 (sc-39101) were purchased (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Transient Transfection and Firefly Luciferase Assay

The 1 × 106 confluent cells in 1 ml of serum-free EMEM were transfected with 3 μg of promoter/luciferase constructs and 0.1 μg of thymidine kinase promoter-driven quantitation control Renilla luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI) by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 48 h of transfection, dual luciferase activities were measured with a Turner BioSystems 20/20n luminometer (Promega). Results are expressed as luciferase activity in relative light units (RLU), the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activities. Transfections were performed in triplicate and replicated in three separate experiments. Knockdown of endogenous expression of c-fos, c-jun, JNK1, or JNK2 was accomplished by transfected with 1 μM of siRNA. Scrambled si-c-fos RNA served as a control.

PD98059 and U0126 Dose Response

To examine the effect of MEK1/2 inhibitors on human ASBT promoter activity, Caco-2 cells were treated for 48 h with increasing concentration of PD98059 (0, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM) or U0126 (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 μM). PD98059 is an inhibitor of MEK1, whereas U0126 is a highly selective and potent inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2 (17).

FGF-19 Dose

To examine the effect of FGF-19 on ASBT protein expression, Caco-2 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of recombinant FGF-19 (0, 50, 100, and 150 μg/μl) for 48 h. For ASBT promoter activity, ASBT, dAP1ASBT(mut), SV40/dAP1, or SV40/ZErO luciferase constructs were transfected into Caco-2 cells treated with 50 μg/μl of FGF-19; 50 μg/μl FGF-19 was chosen to avoid potential nonspecific effects from higher concentrations of FGF-19. Studies in CT-26 cells used the mouse ASBT promoter and 100 μg/μl of FGF-19.

Preparation of Whole Cell Extracts from Cultured Caco-2 Cells

As previously described (3), whole cell extracts (WCE) were prepared from 1 × 106 Caco-2 cells that were suspended in 50 μl of RIPA Lysis buffer and 1× Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Preparation of Total Homogenate, Membrane, Cytoplasmic, and Nuclear Extracts

Total homogenate and membrane proteins were prepared from ileum and gallbladder by modification of a previously described technique (11). Weighted tissue (ileum and gallbladder) was homogenized 10 times by using an OMNI International homogenizer in 10 volumes of ice-cold homogenization buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 20% glycerol and 1× Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail). Tissue lysates were centrifuged at 2,400 g for 10 min, pelleting nonhomogenized tissue debris. The supernatant was used as total-homogenate fraction. For analysis of gallbladder each sample was a combination of tissue from the four mice of the same group.

For isolation of a crude membrane fraction from Caco-2 cells, WCE were used in place of total homogenate fraction. Homogenate from tissues or WCE from Caco-2 cells were spun at 30,590 g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer and spun at 30,590 g for 30 min. The pellet (crude membrane) was resuspended in buffer (300 mM Mannitol, 10 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, pH 7.5 and 1× Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail).

Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were prepared from tissues or cultured cells by using the NE-PER kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein concentrations of all the extracts were determined by using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described (6). The following antibodies were used for these studies: anti-ASBT (sc-27493), anti-JNK1 (F-3, sc-1648), and anti-JNK2 (N-18, sc-827); antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-c-Jun (60A8) rabbit 9165, anti-phospho-c-Jun (Ser 63) 54B3 rabbit 2361, c-Fos (9F6) rabbit 2250, and anti-phospho-c-Fos (Ser 32) D82C12 XP rabbit 5348 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). As a loading control for plasma membrane proteins, anti-Na+-K+-ATPase (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) antibody was used as a loading control for plasma membrane proteins, anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for homogenates or cytoplasmic fractions, and TATA binding protein (Abcam) for nuclear extracts.

Animal Studies

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. Intestinal specific silencing of the c-fos gene was attained by crossing mice harboring a floxed c-fos allele (f/fc-fos) (55) with mice expressing Cre recombinase in the intestine as directed by the villin promoter Tg (Vil-cre) (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) (36). Mouse genotyping was performed by Southern blotting as described (55) and/or by PCR of the neomycin cassette in exon 4 of the c-fos gene, with a forward primer 5′ GGA TTT GAC TGG AGG TCT GC 3′ and a reverse primer neo 5′ TTG AAG CGT GCA GAA TGC 3′ (450 bp) or a reverse primer c-fos 5′ ATG ATG CCG GAA ACA AGA AG 3′ (170 bp). Silencing of c-fos in the intestine was confirmed by Western blot analysis of c-Fos and/or phospho-c-Fos in nuclear extracts from appropriate tissues. Four distinct groups of male mice were ultimately studied, wild type (C57BL6J), c-fos int−/− [homozygous f/fc-fos and hemizygous Tg (Vil-cre)], crecont [hemizygous Tg (Vil-cre)], and c-foshypo (homozygous f/fc-fos). All mice were maintained on ad libitum diet of normal rodent chow and water. Seven days prior to tissue sampling and/or FGF-19 treatment, mice were maintained on Open Source Diet AIN-76A (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ). The effect of FGF-19 was assessed 8 h after intraperitoneal injection of 400 μg/kg body wt of FGF-19, as previously described (47). Control mice received an intraperitoneal injection of the same volume of saline.

There were eight groups in total with four mice in each group. The treatment groups were group 1, wild type (wt)+vehicle; group 2, wt+FGF-19; group 3, c-fos−int+vehicle; group 4, c-fos−int+FGF-19; group 5, crecont+vehicle; group 6, crecont+FGF-19; group 7, c-foshypo+vehicle; and group 8, c-foshypo+FGF-19.

FGF-19 ELISA

FGF-19 was measured in the cytoplasmic extracts (20 μg) of mouse ileal tissues of group 1 through group 8, as described above. The amount of FGF-19 was quantified from a standard curve, following the assay procedure of a solid-phase sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with In-Stat software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Unless otherwise stated, means were compared by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test, all values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

FGF-19 Treatment Represses ASBT in Caco-2 Cells

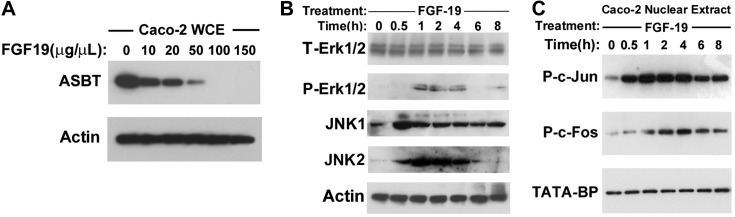

Addition of FGF-19 to the media of Caco-2 cells led to a dose-dependent repression of endogenous ASBT protein in WCE (Fig. 1A). Since 50 μg/μl of FGF-19 led to significant repression of ASBT, this dose of FGF-19 was used in cell culture throughout the study, unless specifically indicated.

Fig. 1.

Effect of fibroblast growth factor-19 (FGF-19) in Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells were treated for 48 h with FGF-19 and protein expression was assessed by Western blotting. A: effect on apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT). Dose-dependent repression of ASBT is observed in Caco-2 cells treated with 10, 20, 50, 100, or 150 μg/μl of recombinant FGF-19. B and C: signaling molecules (B, cytoplasmic; C, nuclear) activated by FGF-19. In response to 50 μg/μl FGF-19 treatment, the abundance of phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK1, and JNK2 in cytoplasmic extracts was increased (A), and phosphorylated c-Jun and c-Fos in nuclear extracts (B) was increased. WCE, whole cell extracts; T-, total; P-, phosphorylated; TATA-BP, TATA binding protein.

Signal Transduction Pathways Initiated by FGF-19 in Caco-2 Cells

Signal transduction pathways activated by FGF-19 were assessed by Western blot analysis of proteins extracted from cytoplasmic (Fig. 1B) and nuclear (Fig. 1C) fractions of Caco-2 cells treated with FGF-19. Within 1 h, there was a transient activation of p-ERK1/2, JNK1 and JNK2 without a change in total ERK1/2 (Fig. 1B). In the nuclear extracts there was similar transient phosphorylation of jun and fos (Fig. 1C).

Silencing MEK1/2 Pathway Activates ASBT

To assess the effect of inhibiting MEK1/2 pathway on ASBT, promoter analysis was performed in Caco-2 cells transfected with pGL3-hASBT along with the MEK1/2 chemical inhibitors PD98059 or U0126. U0126 was added in doses from 1 to 20 μM (49) whereas PD98059 was added in doses from 10 to 100 μM (40). A dose-dependent increase in ASBT promoter activity was observed in response to either PD98059 or U0126, suggesting that the MEK/ERK pathway endogenously represses ASBT (Fig. 2A). U0126 is a more specific and potent inhibitor of the MEK pathway (17). Therefore, U0126 was used in subsequent studies for the inhibition of MEK1/2. U0126 treatment of Caco-2 cells induced a significant increase in endogenous ASBT protein expression (Fig. 2B, no treatment: 233 ± 60 vs. U0126 treatment: 3,307 ± 166 densitometry units, P < 0.0001). U0126 treatment blocked the repressive effect of FGF-19 on the ASBT promoter in Caco-2 cells (control: 86.2 ± 9.1; +FGF-19: 33.7 ± 8.0; +U0126: 153.7 ± 28.2; +FGF-19 and U0126: 117 ± 18.1 RLU; n = 9, see Fig. 2C for relevant statistical comparisons).

Fig. 2.

Effect of MEK1/2 inhibition. Caco-2 cells were treated with MEK1/2 inhibitors and the effect on ASBT was assessed by Western blotting or by measurement of human ASBT promoter activity. A: dose dependence effect on ASBT promoter activity. Dose-dependent activation of human ASBT promoter activity is observed in Caco-2 cells treated with the MEK1/2 inhibitors PD98059 (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mM) or U0126 (0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 mM) (P < 0.001). B: effect of U0126 on ASBT in Caco-2 cells. ASBT protein expression is increased in Caco-2 cells treated with 5 μM U0126 (+) compared with vehicle control (−). Each lane represents a separate experimental group. C: effect of MEK1/2 inhibition on FGF-19 modulation of ASBT promoter activity. ASBT promoter activity was repressed in Caco-2 cells treated with 50 μg/μl FGF-19, whereas it was enhanced by 5 μM U0126. In the presence of U0126, FGF-19 treatment did not lead to a significant reduction in ASBT promoter activity. NS, not significant.

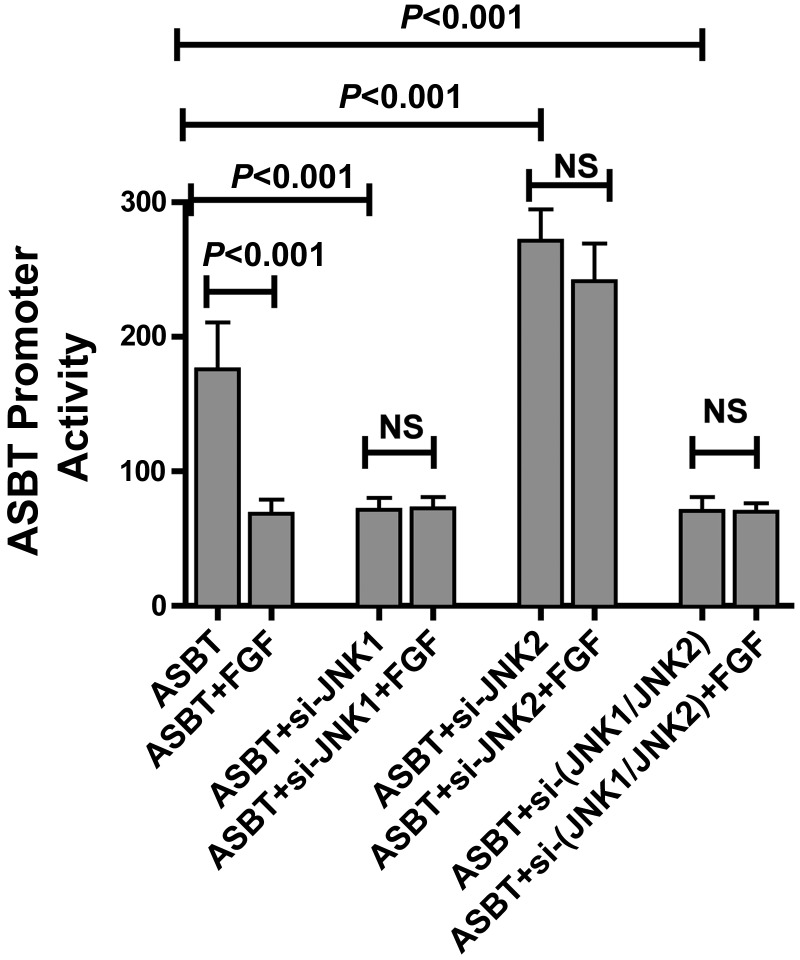

Antagonistic Effects of JNK1 and JNK2 on ASBT Promoter Activity

Our studies (Fig. 1B) suggest that FGF-19 signals through JNK1 and JNK2. To determine the effects of JNK1 and JNK2 on ASBT promoter activity, Caco-2 cells transfected with pGL3-hASBT were pretreated with the silencing constructs for JNK1 and/or JNK2 in the absence or presence of FGF-19. As previously observed, FGF-19 treatment repressed ASBT promoter activity (Fig. 3). Silencing JNK1 led to repression of ASBT whereas silencing JNK2 enhanced ASBT promoter activity. The effect of si-JNK1 or si-JNK2 was observed independent of the addition of exogenous FGF-19 (ASBT: 176 ± 35; +FGF-19: 68 ± 10; +si-JNK1: 71 ± 8; +si-JNK2: 272 ± 23; +si-JNK1+FGF-19: 72 ± 9; +si-JNK2+FGF-19: 287 ± 72; n = 9; see Fig. 3 for relevant statistical comparisons). Moreover, when both JNK-1 and JNK2 were silenced, the effect of silencing JNK1 predominated over JNK2 silencing (+si-JNK1+si-JNK2: 71 ± 10, +si-JNK1+si-JNK2+FGF-19: 70 ± 7) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of JNK1 and JNK2 on FGF-19 modulation of ASBT promoter activity. Caco-2 cells were treated with silencing vectors for JNK1 and/or JNK2. The effect of altering JNK 1 or JNK2 on FGF-19 signaling was tested by treated cells with 50 μg/μl FGF-19. ASBT promoter activity was assessed by use of a luciferase reporter construct. Silencing JNK1 in Caco-2 cells leads to ASBT promoter repression, whereas JNK2 silencing activated ASBT. Moreover, the JNK1 effect predominated when both JNK1 and JNK2 were silenced (P < 0.001 for the comparisons shown on the figure). When JNK1 and/or JNK2 were silenced there was no effect of FGF-19 treatment.

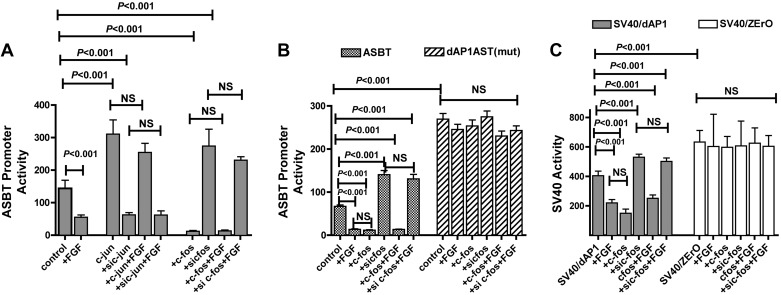

Counterregulatory Effects of c-Jun and c-Fos on the ASBT Promoter

Previous studies have shown that c-Jun is an activator whereas c-Fos is an inhibitor of ASBT (4). To test the hypothesis that FGF-19-mediated repression of ASBT occurs via the AP-1 pathway, c-Jun and c-Fos expression in Caco-2 cells were modulated in presence or absence of FGF-19 (Fig. 4A). As expected, forced expression of c-Jun activated the ASBT promoter whereas silencing the gene repressed ASBT (ASBT: 143 ± 25; +c-jun: 305 ± 43; +si-c-jun: 65 ± 7 RLUs; P < 0.001 for all comparisons). Conversely, c-Fos overexpression repressed the ASBT promoter whereas silencing it activated ASBT (ASBT: 143 ± 25; +c-fos: 12 ± 2; +si-c-fos: 287 ± 31 RLUs; P < 0.001 for all comparisons). Furthermore, when c-Jun or c-Fos expression was modulated, FGF-19 treatment had no effect on the ASBT promoter unlike the repression typically observed with FGF-19 expression.

Fig. 4.

Effect of activator protein-1 (AP-1) on FGF-19 modulation of ASBT promoter activity. All studies were performed in Caco-2 cells. The effect of modulation of AP-1 on FGF-19-mediated repression of ASBT promoter activity was assessed by silencing or overexpressing c-Fos or c-Jun. The cis-element mediating response to c-Fos, dAP-1, was mutated in the human ASBT promoter or in a heterologous SV40 promoter-driven construct. A: counterregulatory effects of c-Jun and c-Fos on ASBT promoter activity. ASBT promoter activity was induced by c-Jun [activation by overexpression (+c-jun) and repression by silencing (si c-jun)] and repressed [repression by overexpression (+c-fos) and activation by silencing (si c-fos)] by c-Fos. Furthermore, when c-Jun or c-Fos expression was modulated, FGF-19 treatment had no effect on the ASBT promoter. B: effect of mutation of the c-Fos cis-element, dAP-1, on ASBT response to FGF-19. The human ASBT promoter construct with a mutation in the dAP-1 element [dAP1ASBT(mut)] had a 3-fold increased basal promoter activity compared with the wild-type promoter. Unlike the wild-type promoter, the dAP1ASBT(mut) was unresponsive to alterations in c-Fos expression or exogenous FGF-19 [P > 0.05, dAP1ASBT(mut) vs. dAP1ASBT(mut)+FGF or +sic-fos or +c-fos]. C: analysis of the role of dAP-1 in mediating responsiveness to FGF-19 in a heterologous system. The specific role of dAP-1 in ASBT promoter response to FGF-19 was assessed by inserting the dAP-1 element in an SV40 heterologous promoter system. Caco-2 cells transfected with SV40/dAP-1 showed marked inhibition in activity in response to either FGF-19 or c-Fos (P < 0.001). The negative control hybrid construct SV40/ZErO containing a 45-bp pZErO plasmid sequence inserted in to the same site as the dAP-1 sequence showed no response to treatment with FGF-19 or c-Fos.

Inhibitory Effect of FGF-19 Is Mediated in Part by the Distal AP-1 Element in the ASBT Promoter

The promoter for ASBT contains two distinct AP-1 binding sites. The distal AP-1 cis-element, dAP-1, mediates inflammatory repression of ASBT via interactions with c-Fos (38). The wild-type construct had predicted responses to FGF-19 and c-Fos (ASBT: 67 ± 10; FGF-19: 14 ± 5; +c-fos: 12 ± 4; +si-c-fos: 140 ± 11; +c-fos+FGF-19: 13 ± 7; +si-c-fos+FGF-19: 130 ± 15 RLUs; n = 9; see Fig. 4B for relevant statistical comparisons) (Fig. 4B). Site-directed point mutation of the dAP-1 element completely abolished ASBT promoter responses to both c-Fos and FGF-19. Basal promoter activity of the mutant promoter was severalfold greater than the wild-type (ASBT) promoter, presumably owing to blocking of endogenous c-Fos repression that exists in Caco-2 cells [ASBT: 67 ± 10; dAP1ASBT(mut): 269 ± 32 RLUs; P < 0.001]. Unlike the wild-type ASBT promoter, no change in the activity of the dAP-1 mutant promoter was observed in response to FGF-19 and/or changes in c-Fos expression. The dAP-1 mutant promoter was responsive to changes in c-Jun as would be expected since the uAP-1 (c-Jun responsive) element is unchanged in this construct (data not shown).

The effects of FGF-19 and c-fos on the ASBT promoter was recapitulated in a heterologous construct driven by the SV-40 promoter, which harbors the dAP-1 element (Fig. 4C). The SV40/dAP-1 promoter activity was reduced by either FGF-19 administration or c-fos transfection and activated by si-c-fos treatment (SV40/dAP-1: 404 ± 32; +FGF: 220 ± 23; +c-fos: 183 ± 15; +si-c-fos: 530 ± 21 RLUs; n = 9, P < 0.001 for all comparisons relative to the baseline construct). When c-Fos expression was modulated the effect of FGF-19 was abrogated (+c-fos+FGF: 251 ± 23; +si-c-fos+FGF: 502 ± 23; P > 0.05 for si-c-fos vs. si-c-fos+FGF or +c-fos vs. +c-fos+FGF). These findings are analogous to the human ASBT promoter reporter results. In contrast and as expected, SV40/pZErO, the negative control dAP1 element-containing construct, showed no change in the promoter activity in response to alterations in c-Fos expression or FGF-19 treatment.

FGF-19-Responsive Regulatory Pathways in CT-26 Cells

The pathways identified in Caco-2 cells were tested in the mouse intestinal cell line, CT-26. As with the Caco-2 line-derived analyses, the ASBT promoter was repressed in response to FGF-19 and activated by treatment with U0126 or in response to silencing of c-fos. U0126 treatment blocked FGF-19-mediated repression, whereas silencing c-fos diminished but did not completely block the response to FGF-19 (control: 28.7 ± 6.5; + FGF: 1.9 ± 0.5; + U0126: 61.8 ± 16.0; + si c-fos: 117.7 ± 14.0; + U0126 + FGF: 47.4 ± 5.4; + si c-fos + FGF: 92.1 ± 6.7, n = 6, P < 0.001 for control vs. FGF or U0126 or si c-fos, P < 0.01 for si c-fos vs. si c-fos + FGF, P > 0.05 for U0126 vs. U0126 + FGF).

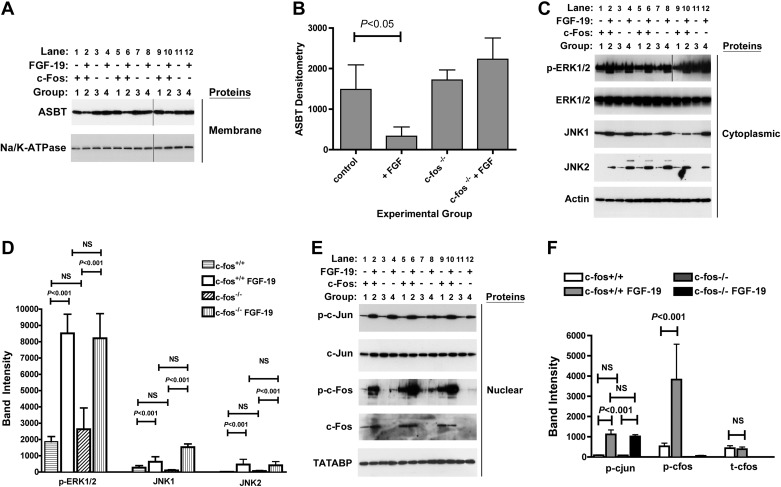

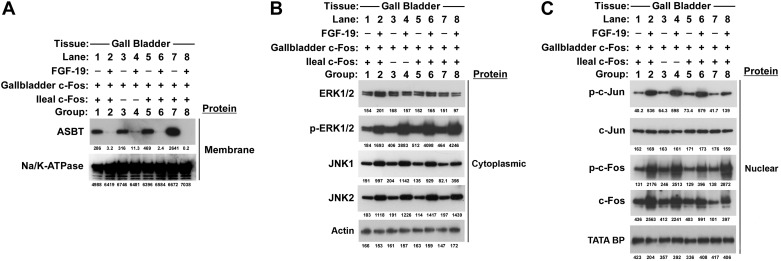

FGF-19 Induced Downregulation of Mouse ASBT in Ileum Is Dependent on c-Fos

As predicted from promoter analysis of ASBT constructs and immunoblotting of FGF-19-treated Caco-2 cells, FGF-19 treatment led to a significant downregulation of ASBT in membrane fractions of mouse ileum [group 2 in Fig. 5, A and B (control: 1,486 ± 606; + FGF-19: 332 ± 230; c-fos−int: 1,720 ± 246; c-fos−int + FGF-19: 2,230 ± 523, densitometry units per μg crude membranes, n = 4 per group, statistical comparisons in Fig. 5B)]. Despite activation of the same signal transduction pathways by FGF-19, ASBT was not repressed in the ileum of mice that did not express c-Fos; in contrast, it was nonsignificantly increased in response to FGF-19 (group 4, Fig. 5, A and B). FGF-19 treatment of the crecont and c-foshypo mice led to significant reductions in ASBT (data not shown). The signal transduction pathways identified in vitro were active in vivo. FGF-19 treatment was associated with induction of JNK1 and JNK2 expression and led to enhanced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in cytoplasmic extracts of ileal tissue (Fig. 5, C and D). c-fos was effectively silenced by the cre-lox strategy used in this breeding, as noted by the minimal or absent c-Fos protein detection in the ileum of group 3 and 4 mice (Fig. 5, E and F). In wild-type as well as in ileal c-fos knockout mice, FGF-19 treatment activated the phosphorylation of c-Jun in nuclear extracts (Fig. 5, E and F). Molecular events were assessed in the gallbladder of the same mice. The villin promoter does not direct expression to the gallbladder and thus as such c-Fos was expressed in the gallbladder of c-fos−int mice (Fig. 6C). The same signal transduction pathways were activated by FGF-19 in the gallbladder and ASBT was repressed in both the wild-type and c-fos−int mice (Fig. 6). Similar results to wild-type mice were observed in ileum (not shown) and gallbladder (Fig. 6) of the crecont and c-foshypo mice. Tissue levels of FGF-19 were quantified in the cytoplasmic extracts of ileal samples from mice treated without (group 1, group 3, group 5, or group 7) or with (group 2, group 4, group 6, or group 8) FGF-19. Detectable and similar levels were measured only in mice treated with FGF-19 (group 2: 4.3 ± 0.2, group 4: 3.3 ± 0.7, group 6: 3.9 ± 0.3, group 8: 4.1 ± 0.8 pg/μg cytosolic protein).

Fig. 5.

Effects of intestinal silencing of c-Fos on FGF-19 mediated responses in the ileum. The role of c-Fos in mediating ileal responses to FGF-19 was assessed in mice with intestinal specific silencing of c-fos. FGF-19 was administered by intraperitoneal injection and tissue samples were obtained 8 h later for Western blot analysis. Two separate sets of mice, wild type and c-fos−int, were untreated (lanes 1, 5, 9 for wild type and lanes 3, 7, 11 for c-fos−int) or treated (lanes 2, 6, 10 for wild type and lanes 4, 8, 12 for c-fos−int) with FGF-19. Ileal protein levels were quantified by Western blot of membrane proteins (10 μg; A), cytoplasmic proteins (5 μg; C), and nuclear proteins (15 μg; E). Results shown are from 3 of 4 replicate samples. Quantitative analyses of all 4 samples are shown in the graphs (B, D, and F). ASBT protein was reduced in FGF-19-treated wild-type mice (group 2; lanes 2, 6, 10) compared with untreated controls (group 1; lanes 1, 5, 9) (A and B). In contrast, ASBT was unchanged in the c-fos−int mice treated with FGF-19 (group 4; lanes 4, 8, 12) compared with untreated c-fos−int mice (group 3; lanes 3, 7, 11) or untreated controls (group 1; lanes 1, 5, 9) (A and B). phosphoERK1/2, JNK-1, and JNK-2 was induced with FGF-19 (C and D). FGF-19 induced phospho-c-jun in wild-type and c-fos−int mice (E and F). FGF-19 increased phospho-c-Fos in wild-type mice compared with untreated controls (E and F). As expected, there was minimal total or phospho-c-Fos expression in the c-fos−int mice untreated or treated with FGF-19 (E and F). In selected circumstances (A and C; phospho-ERK1/2) the images were derived from 2 separate blots as indicated by the vertical line separating results from the 2 blots.

Fig. 6.

Effect of intestinal silencing of c-Fos on FGF-19-mediated responses in the gallbladder. Responses to FGF-19 in gallbladder were assessed in mice with intestinal specific silencing of c-fos as an internal control with normal c-Fos expression, since cre expression was not directed to the gallbladder by villin. FGF-19 was administered by intraperitoneal injection and tissue samples were obtained 8 h later for Western blot analysis. Owing to the small size of the gallbladder, each band shown above for each group results from pooling of the 4 gallbladders into 1 sample per group. Four separate sets of mice were untreated (lane 1, lane 3, lane 5, lane 7 for wild type, c-fos−int, crecont and c-foshypo, respectively) or treated (lane 2, lane 4, lane 6, lane 8 for wild type, c-fos−int, crecont, and c-foshypo, respectively) with FGF-19 and their pooled gallbladder samples (4 for each group) were analyzed by Western blotting with densitometric values below each band. A marked reduction in ASBT protein level was seen in FGF-19-treated wild type, c-fos−int−/−, crecont, and c-foshypo (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, respectively) mice compared with corresponding untreated controls (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) (A, 10 μg protein). Administration of FGF-19 phosphorylated ERK1/2 and increased expression of JNK-1 and JNK-2 proteins (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) in the cytoplasmic extracts of all groups (B, 5 μg protein). FGF-19 increased phospho-c-Jun, phospho-c-Fos and total c-Fos (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8) in the nuclear extracts of all groups (C, 15 μg protein).

DISCUSSION

FGF-19 is an enterokine, which regulates a number of biologically important processes (31). The major focus of most investigations to date has been signaling from the ileum to the liver or gallbladder by FGF-19 in response to bile acids (27, 31). The present studies support the supposition that FGF-19 may also act in an autocrine fashion, leading to negative feedback regulation of intestinal bile acid transport. Intraperitoneal administration of 400 μg/kg of recombinant FGF-19 leads to reproducible and rapid repression of ASBT protein expression in both the ileum and gallbladder. This dosing regimen in these studies is in the range of prior mouse-based experiments and yields tissue concentrations that are in the same order of magnitude of serum concentrations of FGF-19 (30, 34, 50). The high level of secretion of FGF-19 by the gallbladder raises the possibility of autocrine or paracrine signaling to cholangiocytes, thereby altering expression of apical bile acid transport (56). Clearly there are complex systems biology issues present in analyzing the effects of perturbations of the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. The panoply of regulatory mechanisms for bile acid homeostasis ensure tight control of both the size of the bile acid pool and its distribution throughout the body.

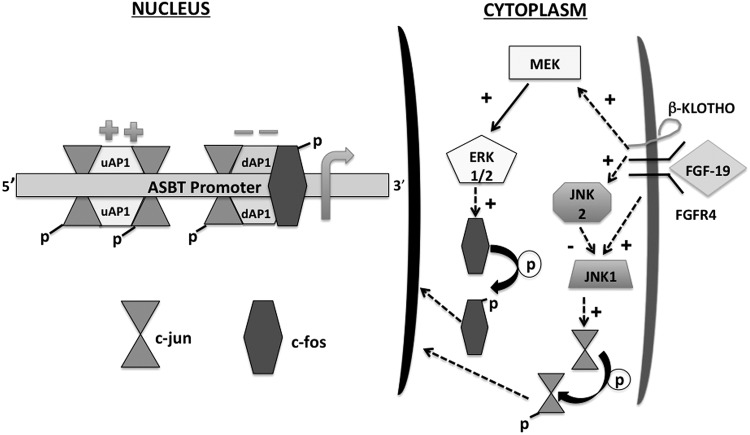

FGF-19-mediated repression of ASBT occurs via the receptor complex of FGFR4 and β-Klotho signaling via mitogen-activated pathways involving MEK, ERK, JNK, and AP-1 (Fig. 7) (43). FGF-19 signals through FGFR4 and β-Klotho to phosphorylate and activate ERK1/2 in a MEK1/2 dependent pathway (33). ERK1/2 phosphorylation was observed in the ileum and gallbladder in response to exogenous FGF-19 administration. Signaling to ASBT was blocked by small molecular inhibitors of MEK1/2. Activated ERK1/2 has the capacity to signal through JNK and also directly via phosphorylation of c-Fos (37, 51). Expression of JNK1 and JNK2 is enhanced in response to FGF-19. JNK1 typically phosphorylates c-Jun and would be expected to activate ASBT. Silencing JNK1 in these studies led to the predicted reduction in ASBT promoter activity. The function of JNK2 remains controversial: it may be a negative regulator of c-Jun (1). Silencing JNK2 activated ASBT, consistent with this supposition. Alterations in JNK in response to FGF-19 may not be the primary pathway for regulation of ASBT expression given the counterregulatory responses and dual activation in response to FGF-19. Phosphorylation of c-Fos appears to be a more predominant mechanism for mediating FGF-19 responses.

Fig. 7.

Model of FGF-19-mediated repression of ASBT expression. FGF-19 binds to a complex of β-Klotho and FGFR4, leading to signaling via MEK and JNK. MEK activates ERK1/2, which phosphorylates c-Fos. Phosphorylated c-Fos translocates to the nucleus and represses ASBT via interaction with the dAP-1 element in the ASBT promoter. Activation of JNK1 leads to phosphorylation of c-Jun and subsequent binding of both the activating upstream AP-1 (uAP-1) site and the repressing dAP-1 site. Activation of JNK2 counterbalances the effect of JNK1 by its inhibition.

The link of FGF-19 to repression of ASBT follows one described for responses to inflammatory cytokines and involves transcriptional repression mediated by binding of a heterodimer of c-Fos and c-Jun to the dAP-1 cis-element in the ASBT promoter (38). The findings in this study provide very strong evidence that this is the primary mechanism of ASBT repression by FGF-19 in the ileum. Ileal ASBT expression was not repressed in FGF-19-treated mice that lack intestinal c-Fos. There was an impression that ASBT might actually be activated in the absence of c-Fos in the ileum in response to FGF-19, which might be predicted from the effect of c-Jun on ASBT. Limited numbers of mice and the counterregulatory effects of JNK1 and JNK2 may have diminished an activation of ASBT. c-fos was not silenced in the gallbladder, thereby establishing an excellent internal control for the role of c-Fos in mediating the effects of FGF-19. Prior studies of the effect of indomethacin-induced ileitis in mice revealed a c-Fos-related inhibition of the basolateral bile acid transporter heterodimer, organic anion solute transporter α/β (38). On the basis of the model suggested by these studies it is possible that FGF-19 would also represses the expression of the organic anion solute transporter α/β.

FGF-19 is also known to repress the expression of cholesterol 7-α hydroxylase (CYP7A1), a key enzyme in bile acid biosynthesis (24). Bile acids exert negative feedback regulation on the transcription of both ASBT and CYP7A1, with the primary mechanism involving FXR mediated activation of the expression of the short heterodimer partner followed by inactivation of permissive transcription factors, like the liver receptor homolog-1 (5, 39). The exact mechanism of FGF-19-mediated repression of CYP7A1 remains controversial but may be FXR independent and operate through a signal pathway similar to that observed in the intestine and gallbladder involving MEK, ERK, and JNK (24, 32, 48, 53). FGF-19 treatment leads to enhanced c-Fos expression in the liver but a link of c-Fos to CYP7A1 is not known (34). In whole animal models and in some cell culture systems it is difficult to dissect out FXR and MAPK signaling pathways, in particular because FGF-19 expression is FXR dependent.

In summary, FGF-19 represses the expression of ASBT in the ileum and gallbladder via a signal transduction pathway involving the cell surface receptors β-Klotho and FGF receptor 4 and the signaling molecules MEK1/2, ERK1/2, JNK1, JNK2, and c-Fos. FGF-19 is well described as an enterokine that acts in a paracrine manner. These studies suggest that autocrine effects in enterocytes and cholangiocytes should be considered in assessing the biology of this interesting signaling molecule. A classical mitogen growth factor signaling pathway terminating in c-Fos is operant in the repression of ASBT and should be considered in other effects of FGF-19.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by grants to B. L. Shneider (NIH NIDDK DK 54165) and to M. Xu (NIH NIDA DA025088).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.G., F.C., M.X., and B.L.S. conception and design of research; A.G., F.C., and S.B. performed experiments; A.G., F.C., and B.L.S. analyzed data; A.G., F.C., and B.L.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.G., F.C., and B.L.S. prepared figures; A.G., F.C., and B.L.S. drafted manuscript; A.G., F.C., S.B., M.X., and B.L.S. edited and revised manuscript; A.G., F.C., S.B., M.X., and B.L.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bode AM, Dong Z. The functional contrariety of JNK. Mol Carcinog 46: 591–598, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen F, Ananthanarayanan M, Emre S, Neimark E, Bull LN, Knisely AS, Strautnieks SS, Thompson RJ, Magid MS, Gordon R, Balasubramanian N, Suchy FJ, Shneider BL. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, type 1, is associated with decreased farnesoid X receptor activity. Gastroenterology 126: 756–764, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen F, Ghosh A, Shneider BL. Phospholipase D2 mediates signaling by ATPase class I type 8B membrane 1. J Lipid Res 54: 379–385, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen F, Ma L, Al-Ansari N, Shneider B. The role of AP-1 in the transcriptional regulation of the rat apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter. J Biol Chem 276: 38703–38714, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen F, Ma L, Dawson P, Sinal C, Sehayek E, Gonzalez F, Breslow J, Ananthanarayanan M, Shneider B. Liver receptor homologue-1 mediated species- and cell line-specific bile acid dependent negative feedback regulation of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter. J Biol Chem 278: 19909–19916, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F, Ma L, Sartor B, Li F, Xiong H, Sun A, Shneider B. Inflammatory-mediated repression of the rat ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter by c-fos nuclear translocation. Gastroenterology 123: 2005–2016, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen F, Shyu AB, Shneider BL. Hu antigen R and tristetraprolin: counter-regulators of rat apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter by way of effects on messenger RNA stability. Hepatology 54: 1371–1378, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Yao X, Young A, McNulty J, Anderson D, Liu Y, Nystrom C, Croom D, Ross S, Collins J, Rajpal D, Hamlet K, Smith C, Gedulin B. Inhibition of apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter as a novel treatment for diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E68–E76, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Chen F, Liu S, Glaeser H, Dawson PA, Hofmann AF, Kim RB, Shneider BL, Pang KS. Transactivation of rat apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter and increased bile acid transport by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 via the vitamin D receptor. Mol Pharmacol 69: 1913–1923, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chey WD, Camilleri M, Chang L, Rikner L, Graffner H. A randomized placebo-controlled phase IIb trial of a3309, a bile acid transporter inhibitor, for chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 106: 1803–1812, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie DM, Dawson PA, Thevananther S, Shneider BL. Comparative analysis of the ontogeny of a sodium-dependent bile acid transporter in rat kidney and ileum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 271: G377–G385, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claro da Silva T, Polli JE, Swaan PW. The solute carrier family 10 (SLC10): beyond bile acid transport. Mol Aspects Med 34: 252–269, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson PA. Bile formation and the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, edited by Johnson LR, Ghishan F, Kaunitz JD, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic, 2012, p. 1461–1506 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson PA, Haywood J, Craddock AL, Wilson M, Tietjen M, Kluckman K, Maeda N, Parks JS. Targeted deletion of the ileal bile acid transporter eliminates enterohepatic cycling of bile acids in mice. J Biol Chem 278: 33920–33927, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duane W. Abnormal bile acid absorption in familial hypertriglyceridemia. J Lipid Res 36: 96–107, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duboc H, Rajca S, Rainteau D, Benarous D, Maubert MA, Quervain E, Thomas G, Barbu V, Humbert L, Despras G, Bridonneau C, Dumetz F, Grill JP, Masliah J, Beaugerie L, Cosnes J, Chazouilleres O, Poupon R, Wolf C, Mallet JM, Langella P, Trugnan G, Sokol H, Seksik P. Connecting dysbiosis, bile-acid dysmetabolism and gut inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 62: 531–539, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS, Van Dyk DE, Pitts WJ, Earl RA, Hobbs F, Copeland RA, Magolda RL, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 18623–18632, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figge A, Lammert F, Paigen B, Henkel A, Matern S, Korstanje R, Shneider B, Chen F, Stoltenberg E, Spatz K, Hoda F, Cohen D, Green R. Hepatic over-expression of murine Abcb11 increases hepatobiliary lipid secretion and reduces hepatic steatosis. J Biol Chem 2790–2799: 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankenberg T, Miloh T, Chen FY, Ananthanarayanan M, Sun AQ, Balasubramaniyan N, Arias I, Setchell KD, Suchy FJ, Shneider BL. The membrane protein ATPase class I type 8B member 1 signals through protein kinase C zeta to activate the farnesoid X receptor. Hepatology 48: 1896–1905, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankenberg T, Rao A, Chen F, Haywood J, Shneider BL, Dawson PA. Regulation of the mouse organic solute transporter α-β, Ostα-Ostβ, by bile acids. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G912–G922, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halpern MD, Weitkamp JH, Mount Patrick SK, Dobrenen HJ, Khailova L, Correa H, Dvorak B. Apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter upregulation is associated with necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G623–G631, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higaki J, Hara S, Takasu N, Tonda K, Miyata K, Shike T, Nagata K, Mizui T. Inhibition of ileal Na+/bile acid cotransporter by S-8921 reduces serum cholesterol and prevents atherosclerosis in rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 1304–1311, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann AF. Inappropriate ileal conservation of bile acids in cholestatic liver disease: homeostasis gone awry. Gut 52: 1239–1241, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt JA, Luo G, Billin AN, Bisi J, McNeill YY, Kozarsky KF, Donahee M, Wang DY, Mansfield TA, Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Jones SA. Definition of a novel growth factor-dependent signal cascade for the suppression of bile acid biosynthesis. Genes Dev 17: 1581–1591, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG, Luo G, Jones SA, Goodwin B, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2: 217–225, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito S, Fujimori T, Furuya A, Satoh J, Nabeshima Y, Nabeshima Y. Impaired negative feedback suppression of bile acid synthesis in mice lacking betaKlotho. J Clin Invest 115: 2202–2208, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones SA. Physiology of FGF15/19. Adv Exp Med Biol 728: 171–182, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung D, Fantin AC, Scheurer U, Fried M, Kullak-Ublick GA. Human ileal bile acid transporter gene ASBT (SLC10A2) is transactivated by the glucocorticoid receptor. Gut 53: 78–84, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung D, Fried M, Kullak-Ublick G. Human apical sodium-dependent bile salt transporter gene (SLC10A2) is regulated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a. J Biol Chem 277: 30559–30566, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kir S, Beddow SA, Samuel VT, Miller P, Previs SF, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Shulman GI, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science 331: 1621–1624, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kir S, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Roles of FGF19 in liver metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 76: 139–144, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong B, Wang L, Chiang JY, Zhang Y, Klaassen CD, Guo GL. Mechanism of tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor in suppressing the expression of genes in bile-acid synthesis in mice. Hepatology 56: 1034–1043, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurosu H, Choi M, Ogawa Y, Dickson AS, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, Mohammadi M, Rosenblatt KP, Kliewer SA, Kuro-o M. Tissue-specific expression of betaKlotho and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor isoforms determines metabolic activity of FGF19 and FGF21. J Biol Chem 282: 26687–26695, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin BC, Wang M, Blackmore C, Desnoyers LR. Liver-specific activities of FGF19 require Klotho beta. J Biol Chem 282: 27277–27284, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma L, Juttner M, Kullak-Ublick GA, Eloranta JJ. Regulation of the gene encoding the intestinal bile acid transporter ASBT by the caudal-type homeobox proteins CDX1 and CDX2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G123–G133, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madison BB, Dunbar L, Qiao XT, Braunstein K, Braunstein E, Gumucio DL. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem 277: 33275–33283, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen RH, Fingar DC, Blenis J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat Cell Biol 4: 556–564, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neimark E, Chen F, Li X, Magid MS, Alasio TM, Frankenberg T, Sinha J, Dawson PA, Shneider BL. c-Fos is a critical mediator of inflammatory-mediated repression of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter. Gastroenterology 131: 554–567, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neimark E, Chen F, Li X, Shneider BL. Bile acid-induced negative feedback regulation of the human ileal bile acid transporter. Hepatology 40: 149–156, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newton R, Cambridge L, Hart LA, Stevens DA, Lindsay MA, Barnes PJ. The MAP kinase inhibitors, PD098059, UO126 and SB203580, inhibit IL-1beta-dependent PGE(2) release via mechanistically distinct processes. Br J Pharmacol 130: 1353–1361, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oelkers P, Kirby LC, Heubi JE, Dawson PA. Primary bile acid malabsorption caused by mutations in the ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter gene (SLC10A2). J Clin Invest 99: 1880–1887, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Root C, Smith CD, Sundseth SS, Pink HM, Wilson JG, Lewis MC. Ileal bile acid transporter inhibition, CYP7A1 induction, and antilipemic action of 264W94. J Lipid Res 43: 1320–1330, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roskoski R., Jr. ERK1/2 MAP kinases: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Res 66: 105–143, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarwar Z, Annaba F, Dwivedi A, Saksena S, Gill RK, Alrefai WA. Modulation of ileal apical Na+-dependent bile acid transporter ASBT by protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G532–G538, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shih D, Bussen M, Sehayek E, Ananthanarayanan M, Shneider B, Suchy F, Shefer S, Bollileni J, Gonzalez F, Breslow J, Stoffel M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1a is an essential regulator of bile acid and plasma cholesterol metabolism. Nat Genet 27: 375–382, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu M, Li J, Maruyama R, Inoue J, Sato R. FGF19 (fibroblast growth factor 19) as a novel target gene for activating transcription factor 4 in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochem J 450: 221–229, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sinha J, Chen F, Miloh T, Burns RC, Yu Z, Shneider BL. beta-Klotho and FGF-15/19 inhibit the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter in enterocytes and cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G996–G1003, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song KH, Li T, Owsley E, Strom S, Chiang JY. Bile acids activate fibroblast growth factor 19 signaling in human hepatocytes to inhibit cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene expression. Hepatology 49: 297–305, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabu K, Kimura T, Sasai K, Wang L, Bizen N, Nishihara H, Taga T, Tanaka S. Analysis of an alternative human CD133 promoter reveals the implication of Ras/ERK pathway in tumor stem-like hallmarks. Mol Cancer 9: 39, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walters JR, Tasleem AM, Omer OS, Brydon WG, Dew T, le Roux CW. A new mechanism for bile acid diarrhea: defective feedback inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: 1189–1194, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wortzel I, Seger R. The ERK cascade: distinct functions within various subcellular organelles. Genes Cancer 2: 195–209, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xia X, Roundtree M, Merikhi A, Lu X, Shentu S, Lesage G. Degradation of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in cholangiocytes. J Biol Chem 279: 44931–44937, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu C, Wang F, Jin C, Huang X, McKeehan WL. Independent repression of bile acid synthesis and activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by activated hepatocyte fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) and bile acids. J Biol Chem 280: 17707–17714, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu C, Wang F, Kan M, Jin C, Jones RB, Weinstein M, Deng CX, McKeehan WL. Elevated cholesterol metabolism and bile acid synthesis in mice lacking membrane tyrosine kinase receptor FGFR4. J Biol Chem 275: 15482–15489, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J, Zhang D, McQuade JS, Behbehani M, Tsien JZ, Xu M. c-fos regulates neuronal excitability and survival. Nat Genet 30: 416–420, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zweers SJ, Booij KA, Komuta M, Roskams T, Gouma DJ, Jansen PL, Schaap FG. The human gallbladder secretes fibroblast growth factor 19 into bile: towards defining the role of fibroblast growth factor 19 in the enterobiliary tract. Hepatology 55: 575–583, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]