Abstract

Antifolates, in particular methotrexate (MTX), have been widely used in the treatment of primary and secondary tumors of the central nervous system (CNS). Pemetrexed (PMX) is a novel antifolate that also exhibits potent antitumor activity against CNS malignancies. Studies have shown that brain distribution of both antifolates is significantly restricted, possible due to active efflux transport at the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This study characterizes the brain-to-blood transport of PMX and MTX and examines the role of several efflux transporters in brain distribution of the antifolates by use of the intracerebral microinjection technique (brain efflux index). The results from this study show that both PMX and MTX undergo saturable efflux transport across the BBB, with elimination half-lives of approximately 39 minutes and 29 minutes, respectively. Of the various efflux transporters this study investigated, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (Mrp2) does not play an important role in the brain distribution of the two antifolate drugs. Interestingly, breast-cancer resistance protein (Bcrp) makes a significant contribution to the brain elimination of MTX but not PMX. In addition, the brain-to-blood transport of both antifolates was inhibited by probenecid and benzylpenicillin, suggesting the involvement of organic anion transporters in the efflux of these compounds from the brain, with organic anion transporter 3 (Oat3) being a possibility. Our results suggest that one of the underlying mechanisms behind the limited brain distribution of PMX and MTX is active efflux transport processes at the BBB, including a benzylpenicillin-sensitive transport system and/or the active transporter Bcrp.

Introduction

Despite scientific advances in understanding the causes and treatment of human malignancies, the treatment of brain tumors, both primary and metastatic, remains a persistent challenge. Many chemotherapeutic agents that are potent and efficacious against peripheral tumors have been found to be ineffective in treating tumors in the brain. In general, the poor response of central nervous system (CNS) tumors to chemotherapy drugs is multifactorial, but the inability to effectively deliver therapeutic agents to the CNS across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is certainly a well known mechanism (Pardridge, 2001; Motl et al., 2006). The BBB is a highly developed defense mechanism that separates the brain from the peripheral circulation, thereby protecting it from circulating toxins and potentially harmful chemicals. The barrier is formed by a dense network of brain capillaries where the endothelial cells contain tight junctions, which limit paracellular transport. In addition, the barrier function is further strengthened by the expression of active efflux transporters in the endothelium. These efflux pumps mediate the brain-to-blood efflux of substrate drugs, thus limiting their CNS exposure (Pardridge, 1999; Allen and Smith, 2001; Golden and Pollack, 2003). Drug efflux pumps present at the BBB include ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as P-glycoprotein (MDR1/ABCB1), breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2), and multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP2/ABCC2, MRP4/ABCC4), as well as transporters of the solute carrier family such as organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1A2 (SLCO1A2) and organic anion transporter 3 (OAT3, SLC22A8) (Miller et al., 2000; Sugiyama et al., 2001; Urquhart and Kim, 2009). Efflux transport mediated by these pumps has been shown to be an important determinant of drug partitioning into the brain.

Primary CNS lymphoma, a rare form of extranodal lymphoma, accounts for approximately 3 to 4% of brain tumors diagnosed every year in the United States. Despite high rates of response after whole-brain radiotherapy, rapid recurrence is common, and long-term survival is rare (Norden et al., 2011). The classic antifolate agent methotrexate (MTX) is widely used for the treatment of primary CNS lymphoma and chemotherapy; MTX in combination with whole-brain radiotherapy has become the treatment of choice. A recent study has reported that high-dose MTX alone or in combination with other therapies is the most effective treatment available for primary CNS lymphoma (Gerstner et al., 2008). Although it is efficacious, high-dose MTX therapy is associated with severe systemic and neurologic toxicities, with complications in some cases leading to patient death. Most of the systemic toxicities can be attributed to the greater tissues exposure after treatment with MTX at high doses, a need arising from the inability of MTX to penetrate the BBB. Preclinical studies have shown that brain distribution of MTX is severely restricted: only 5% of the free drug in plasma crosses the BBB to reach the brain (Devineni et al., 1996; Dai et al., 2005). In humans, Blakeley et al. (2009) also reported poor cerebral penetration of MTX (3.2 to 9.4%) using the microdialysis technique in patients who have recurrent high-grade gliomas. Pemetrexed (PMX [Alimta]) is a novel antifolate that was developed to overcome some of the problems associated with MTX therapy. It has been reported to have potent antitumor activity against a variety of tumors including CNS malignancies (Kuo and Recht, 2006). However, similar to MTX, distribution of PMX across the BBB is also very limited (Dai et al., 2005). The mechanisms behind the poor brain penetration of PMX and MTX are not well understood; one plausible explanation has been the involvement of efflux transport systems at the BBB.

We hypothesized that efflux transporters at the BBB, such as Mrp2, Bcrp, and OATs, mediate the efflux of PMX and MTX from the brain, thereby restricting their brain penetration. We investigated the role of efflux transporters in the brain elimination of antifolates by use of the brain efflux index (BEI; intracerebral microinjection) method. We used transgenic mice lacking the transporters Mrp2 or Bcrp to characterize the involvement of the two transporters in the efflux of PMX and MTX from the brain. In addition, the involvement of OATs was studied by examining the effect of the OAT inhibitors probenecid and benzylpenicillin on the brain-to-blood transport of MTX and PMX.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

[3H]-pemetrexed was a kind gift from Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN). [3H]-methotrexate, [3H]-valproic acid, and [14C]-carboxyl-inulin were obtained from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). Probenecid and benzylpenicillin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Animals.

Male wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Taconic Farms, Inc. (Germantown, NY). Bcrp1−/− and Mrp2−/− mice of a C57 background were a generous gift from Eli Lilly and Company. All animals were maintained under temperature-controlled conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and were allowed food and water ad libitum. The mice were allowed to acclimatize for a minimum of 1 week upon arrival. All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota.

Brain Efflux Index Method.

The brain efflux study was performed using the intracerebral microinjection technique, as previously reported elsewhere (Kakee et al., 1996). Wild-type Mrp2−/− and Bcrp1−/− mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal dose of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Boynton Health Service Pharmacy, Minneapolis, MN), and then were mounted on a stereotaxic device. A borehole was made 3.8 mm lateral to the bregma, and an injection needle was advanced to a depth of 2.5 mm from the surface of the scalp, that is, into the secondary somatosensory cortex 2 (S2) region. Then, 0.2 µl of a mixture of [3H]-pemetrexed (10 nCi/ml) or [3H]-methotrexate (10 nCi/ml) and [14C]-carboxyl-inulin (10 nCi/ml) dissolved in extracellular fluid (ECF) buffer (122 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3mM KCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM D-glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) was injected over 2 minutes using a 2.5-µl microsyringe (Hamilton, Reno, NE) fitted with a fine needle (32 gauge; Hamilton). The injection process was controlled by a Quintessential stereotaxic injector (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL). Time zero was defined as the time when the injection was completed. After injection, the needle was left in place for additional 4 minutes to minimize the backflow of injected solution along the injection track.

At designated time points after injection, the mice were euthanized and decapitated. The right (ipsilateral) and left (contralateral) cerebrum and cerebellum were harvested, weighed, and homogenized in 3 volumes of 5% bovine serum albumin solution. A 100-µl sample of brain homogenate from the right and left cerebrum and cerebellum was mixed with 4 ml of scintillation fluid (ScintiSafe Econo Cocktail; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the associated radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter (LS-6500 instrument; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

The concentration-dependent efflux of [3H]-pemetrexed across the BBB was examined by injecting a solution containing 1 mM and 50 mM unlabeled PMX in addition to a trace amount of [3H]-pemetrexed and [14C]-carboxyl-inulin. To examine the inhibitory effect of probenecid and benzylpenicillin on the brain efflux of [3H]-pemetrexed, 100 mM probenecid or benzylpenicillin was dissolved in the injection solution. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.4. The inhibitory effect was evaluated by comparing the percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the brain in the presence and absence of the inhibitor at 30 minutes after injection.

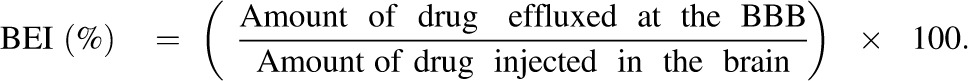

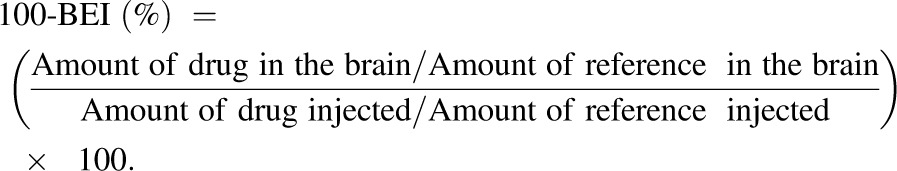

The BEI, defined as the percentage of test drug transported from the ipsilateral cerebrum to the circulating blood across the BBB, compared with the amount of test drug injected into the cerebrum (Kakee et al., 1996), is given by eq. 1:

|

(1) |

100-BEI (%), defined as the percentage of the amount of test drug remaining in the ipsilateral cerebrum compared with the amount of drug injected, is calculated as the amount of test drug retained in the ipsilateral cerebrum divided by the amount of test drug injected, normalized by the corresponding ratio of the BBB impermeable marker (eq. 2):

|

(2) |

The apparent BBB efflux rate constant, keff, was obtained from the slope of the semilogarithmic plot of the value of (100-BEI) versus time using the linear regression function in SigmaPlot (version 9.0.1; Systat Software, Chicago, IL).

Determination of Brain Volume of Distribution by the Brain Slice Uptake Method.

The volume of distribution of PMX and MTX in the brain was determined by the in vitro brain slice uptake technique. Brain slices were prepared according to the method reported by Kakee et al. (1996). In brief, coronal brain slices of the cortex (400 μm) were prepared using a Vibratome (series 1000; Vibratome Company, Bannockburn, IL). The slices were preincubated at 37°C for 5 minutes in ECF buffer oxygenated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After preincubation, the slices were transferred into 5 ml of oxygenated ECF buffer containing [3H]-pemetrexed or [3H]-methotrexate (0.3 μCi/ml) and [14C]-sucrose (0.06 μCi/ml) at 37°C. At designated time points, the slices were removed from the drug solution, dried on filter paper, and weighed. The radioactivity associated with the slice was determined by liquid scintillation counting (LS-6500; Beckman Coulter). The brain volume of distribution (Vd,brain) was calculated as the amount of test drug in the brain slice divided by the medium concentration. The volume of distribution was corrected for the volume of adhering fluid, which was determined as the zero-time intercept of the [14C]-inulin uptake profile: 0.096 mL/g brain. As shown in eq. 3, the apparent brain efflux clearance (Clapp,efflux) was calculated as the product of the elimination rate constant (keff) obtained from the BEI study and brain distribution volume (Vd,brain) obtained from the brain slice uptake study:

| (3) |

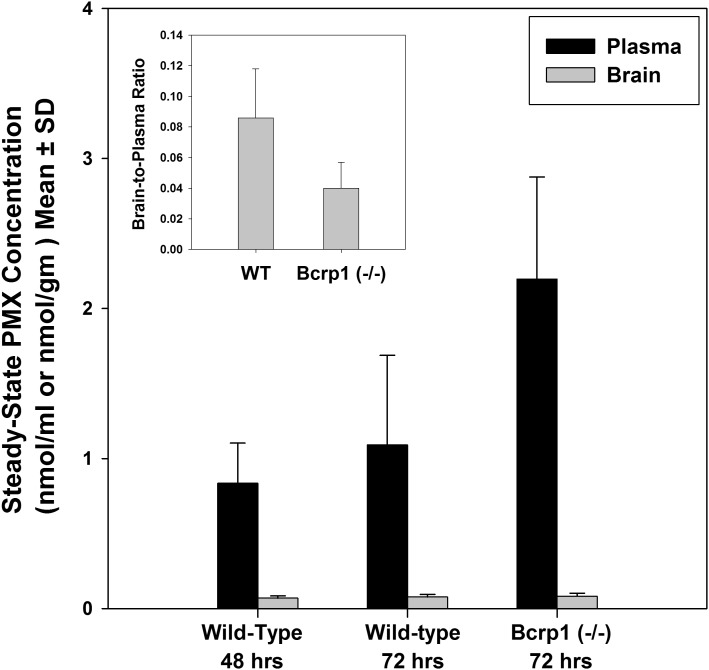

Steady-State Brain Distribution of Pemetrexed.

In addition to the BEI study, the steady-state brain distribution of PMX was examined in wild-type and Bcrp1−/− mice. Alzet osmotic minipumps (Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA) were used to continuously infuse drug into the peritoneal cavity for 72 hours. The pump operated at a flow rate of 1 µl/h, resulting in a constant rate infusion of 25 mg/kg per day. Wild-type mice (n = 5) and Bcrp1−/− mice (n = 5) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal dose of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Boynton Health Service Pharmacy, Minneapolis, MN). A small midline incision was made in the abdominal wall, and the pumps were surgically implanted into the peritoneal cavity. The animals were allowed to recover on a heated pad and were administered ibuprofen in their drinking water for pain relief. The animals were euthanized after 72 hours by using a CO2 chamber. Blood was immediately harvested via cardiac puncture and collected in tubes preloaded with potassium EDTA (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Whole brain was immediately harvested, rinsed with ice-cold saline to remove extraneous blood, and flash frozen using liquid nitrogen. Plasma was isolated from the blood by centrifugation at 3000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. All samples were stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Quantification of Pemetrexed by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectometry.

Mouse plasma and brain samples were analyzed by a rapid and sensitive liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectometry analysis. Whole brain samples were first homogenized in a solution composed of water and ethanol (20:80) with a volume ratio of 1:3. Acetonitrile containing the internal standard (20 ng/ml) was then added to the plasma or brain homogenate, followed by centrifugation to remove the precipitated proteins. The supernatant was diluted with two volumes of water and was chromatographed under reverse-phase conditions on a Betasil C18 analytical column (2.1 × 20 mm, 5 µm particle size; Thermo Electron Corp., Edina, MN). A gradient mobile phase was used with solvent A containing water, trifluoroacetic acid, and 1 mM ammonium bicarbonate (2000:8:2, v:v:v), and solvent B containing acetonitrile, trifluoroacetic acid, and 1 mM ammonium bicarbonate (2000:8:2, v:v:v). The injection volume was 10 µl. PMX detection was accomplished by tandem mass spectrometry using the parent ion m/z ratio of 428.1 and the daughter ion m/z ratio of 281.1. The lower limit of quantification was 1 ng/ml.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SigmaStat (version 3.1; Systat Software). Statistical comparisons between two groups were made by using a two-sample t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance with the Holm-Sidak post hoc test for multiple comparisons, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BEI Method To Characterize the Brain-to-Blood Transport of Pemetrexed and Methotrexate.

The BEI method, also referred to as the intracerebral microinjection technique, is a novel technique to study the mechanisms of brain-to-blood efflux transport at the BBB (Kakee et al., 1996; Kusuhara et al., 2003). Because it isolates efflux processes directly rather than considering efflux as modulator of brain distribution, BEI is an excellent method for determining efflux clearance and studying the mechanisms behind active transport of compounds from the brain. This in vivo method has been extensively used to study the brain efflux clearance of various compounds, including steroid conjugates, valproic acid, nucleoside analogs, buprenorphine, human amyloid-β peptide, and benzylpenicillin and quinidine (Kusuhara et al., 1997; Takasawa et al., 1997; Sugiyama et al., 2001; Kakee et al., 2002; Ohtsuki et al., 2002; Kikuchi et al., 2003; Ito et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2007). In our study, we first validated the technique by studying the brain efflux index of valproic acid. The brain elimination half-life of valproic acid was determined to be 2 minutes (range: 1.6–2.3 minutes, N = 3), a value that is consistent with the reported value of 3.7 minutes from previous studies using the same technique (Kakee et al., 2002). The close agreement of our valproic acid results with the values from the literature supports our brain microinjection technique for the examination of the mechanisms responsible for the brain efflux of PMX and MTX (Kakee et al., 2002). In addition, throughout the course of the efflux studies, less than 0.5% of injected [3H]-pemetrexed or [3H]-methotrexate was found in the contralateral cerebrum and cerebellum, suggesting that diffusion into the rest of the CNS from the injection site was very limited. The percentage of [14C]-carboxyl-inulin (BBB impermeable marker) remaining in the brain did not change significantly for over 90 minutes after injection, indicating little damage to the BBB.

Pemetrexed and Methotrexate Elimination from Mouse Brain.

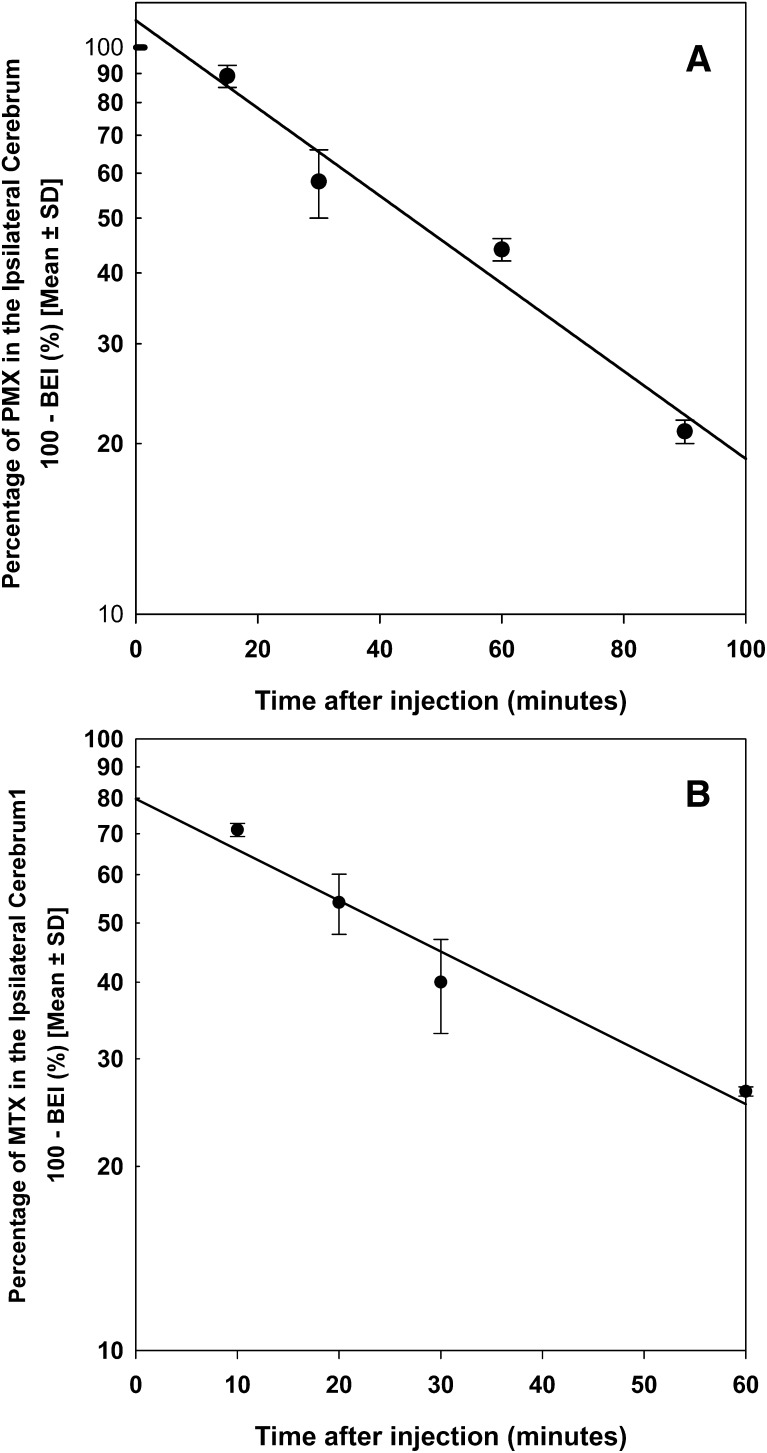

The efflux of MTX and PMX from the mouse brain was investigated using the BEI method. Figure 1A shows the time profile of the percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the brain after intracerebral microinjection. Approximately 80% of the administered dose of [3H]-pemetrexed was eliminated from the brain within 90 minutes. The apparent elimination rate constant (keff) of PMX was estimated to be 1.06 ± 0.18 hour−1, corresponding to a half-life of 0.65 hours. The keff value for MTX was 1.42 ± 0.16 hour−1, resulting in a half-life of 0.48 hours (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Brain efflux index of pemetrexed and methotrexate. The percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the ipsilateral cerebrum was studied for up to 90 minutes after intracerebral injection (A). The percentage of [3H]-methotrexate remaining in the ipsilateral cerebrum was studied for up to 60 minutes after intracerebral injection (B). The solid line was obtained by the regression analysis. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3–4).

Concentration-Dependent Efflux of Pemetrexed at the BBB.

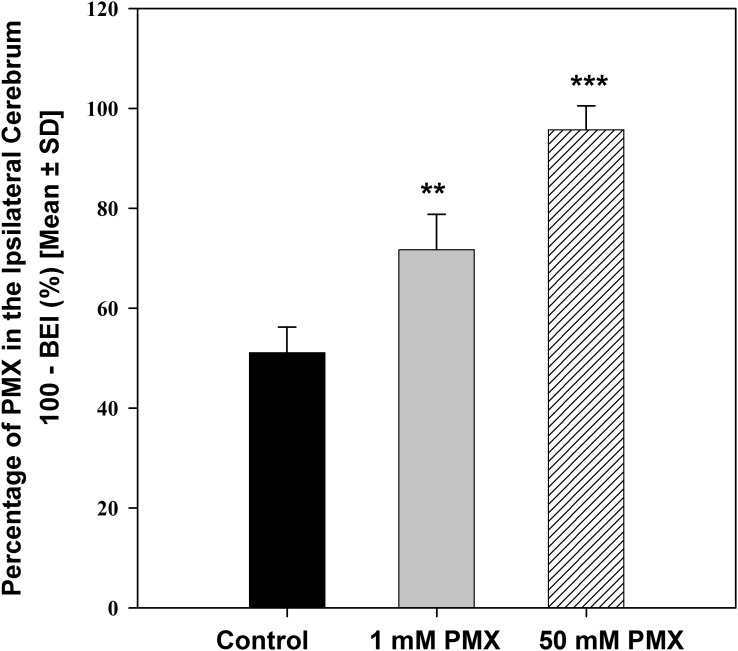

Figure 2 shows that the percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the brain significantly increased after the injection of higher doses of total PMX (unlabeled and [3H]-pemetrexed). Specifically, 51.1% ± 5.1% of [3H]-pemetrexed was retained in the ipsilateral cerebrum 30 minutes after injection of the trace amount of [3H]-pemetrexed (0.1µM). However, in the presence of 1 mM and 50 mM unlabeled PMX in the injectate, the percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the brain increased significantly to 71.7% ± 7.1% and 95.7% ± 4.8%, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 1). This shows that PMX elimination from the brain is saturable, indicating the involvement of a carrier-mediated process.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effect of unlabeled pemetrexed (1 and 50 mM in the injectate) on the efflux of [3H]-pemetrexed from the mouse brain at 30 minutes after the dose. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3∼4). **P < 0.01 compared with control; ***P < 0.001 compared with control.

TABLE 1.

Effect of various treatments on brain-to-blood transport of pemetrexed

| [3H]-Pemetrexed | Concentration in the Injectate (mM) | Concentration in the Brain (mM)a | BEI (%)b | Percentage of Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (control) | — | — | 48.9 ± 5.1 | 100.0 |

| Mrp2−/− | — | — | 58.3 ± 3.3c | 100.4d |

| Bcrp1−/− | — | — | 43.9 ± 2.1 | 89.7 |

| WT + pemetrexed | 1 | 0.025 | 28.3 ± 7.1e | 57.8 |

| WT + pemetrexed | 50 | 1.253 | 4.3 ± 4.8e | 8.8 |

| WT + probenecid | 100 | 2.506 | 27.6 ± 3.3e | 56.5 |

| WT + benzylpenicillin | 100 | 2.506 | 12.2 ± 4.0e | 25.0 |

BEI, brain efflux index; WT, wild type.

Brain concentrations were estimated by dividing the injectate concentration by the dilution factor of 39.9, as previously reported elsewhere (Kakee et al., 1996).

Percentage of pemetrexed eliminated from the ipsilateral cerebrum at 30 minutes.

Percentage of pemetrexed eliminated from the ipsilateral cerebrum at 60 minutes.

Percentage of control normalized by the value of wild-type mice at 60 minutes.

P < 0.001.

Role of Mrp2 in Transport of Pemetrexed and Methotrexate at the BBB.

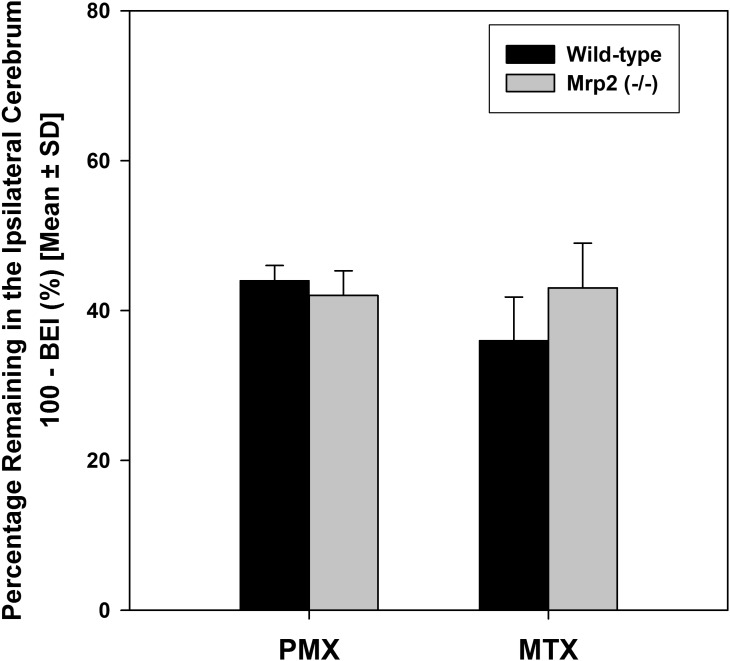

The role of Mrp2 in elimination of PMX and MTX from mouse brain was investigated using Mrp2−/− mice. At 60 minute postdose, the percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the ipsilateral cerebrum of Mrp2−/− mice was not statistically different than that in the wild-type mice (Fig. 3). This indicates that absence of Mrp2 alone does not affect the brain-to-blood transport of PMX. A similar result was found for MTX where elimination of MTX from brain was not different between the wild-type and Mrp2−/− mice (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed and [3H]-methotrexate in the brain of wild-type and Mrp2 deficient (Mrp2−/−) mice at 60 or 30 minutes after administration.

Role of Bcrp in Transport of Pemetrexed and Methotrexate at the BBB.

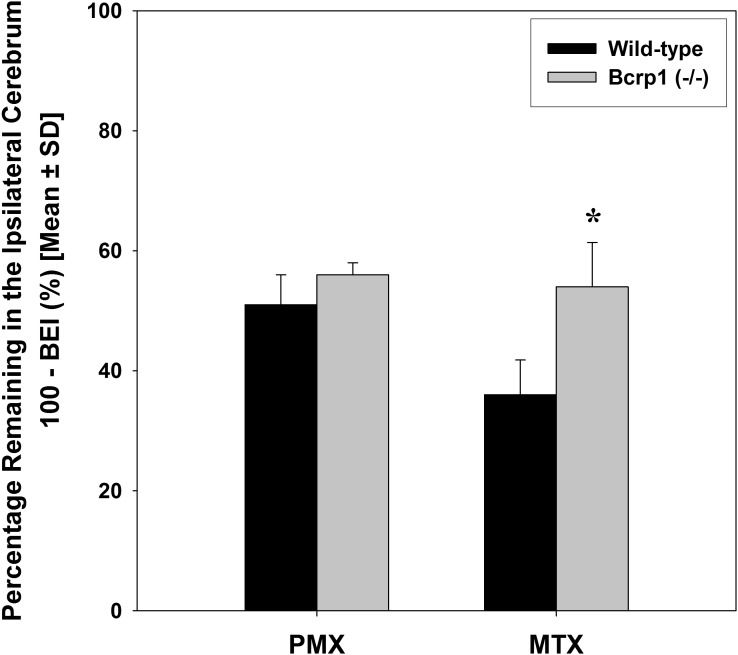

The role of Bcrp in brain-to-blood transport of PMX and MTX at the BBB was studied using the BEI method as well as by determining the steady-state brain partitioning in wild-type and Bcrp1−/− mice. The results from the BEI study show that the percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the brain of Bcrp1−/− mice was not significantly different from that in wild-type mice, suggesting a minor role of Bcrp in the brain-to-blood transport of PMX across the BBB (Fig. 4). This was further confirmed in the 72-hour infusion study, where no statistically significant difference was found in steady-state brain-to-plasma ratios of PMX between the wild-type mice and Bcrp1−/− mice (Fig. 5). The achievement of steady-state in this study was confirmed by the statistical comparison of PMX concentrations in both brain and plasma after 48-hour and 72-hour infusions in the wild-type mice. In contrast to PMX, the results from BEI study suggest the involvement of Bcrp in efflux of MTX at the BBB, i.e., the efflux of [3H]-methotrexate decreased significantly in the Bcrp1−/− mice relative to the wild-type mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The remaining percentage of [3H]-pemetrexed and [3H]-methotrexate in the brain of wild-type and Bcrp deficient (Bcrp1−/−) mice at 30 minutes after the dose. *P < 0.05 compared with WT control.

Fig. 5.

Steady-state pemetrexed brain and plasma concentration in wild-type (WT) and Bcrp deficient (Bcrp1−/−) mice after 2 or 3 days of i.p. administration via osmotic minipump. The inset shows the steady-state brain-to-plasma ratio at 72 hours in wild-type and BCRP knockout mice. Values shown are mean ± S.D. (n = 4).

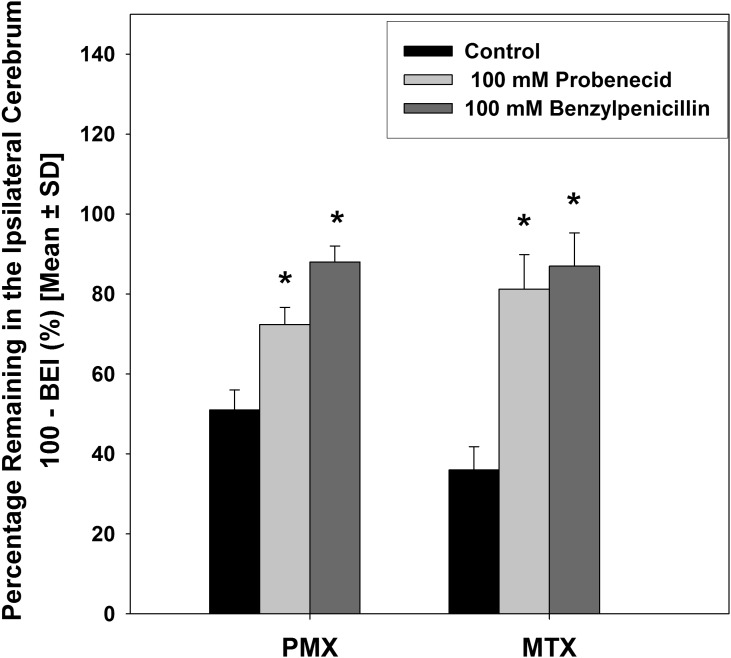

Role of Organic Anion Transporters in Elimination of Pemetrexed and Methotrexate from Mouse Brain.

Probenecid is a nonspecific inhibitor of organic anion transporters, including MRPs, organic anion transporters (OATs), and organic anion-transporting polypeptides (Bakos et al., 2000; Sugiyama et al., 2001; Haimeur et al., 2004). In our study, the involvement of organic anion transporters in brain-to-blood transport of the two antifolates was determined by examining the inhibitory effect of probenecid (Fig. 6). In wild-type mice, simultaneous injection of probenecid (100 mM in the injectate) significantly increased the fraction of [3H]-pemetrexed remaining in the brain from 51.1% ± 5.1% to 72.4% ± 3.3% and [3H]-methotrexate remaining in the brain from 36.2% ± 5.2% to 75.8% ± 8.6%. The substantially diminished efflux of PMX and MTX from the mouse brain in the presence of probenecid indicates the involvement of one or more organic anion transport proteins.

Fig. 6.

Inhibitory effect of probenecid (100 mM in the injectate) and benzylpenicillin (100 mM in the injectate) on the remaining percentage of [3H]-methotrexate and [3H]-pemetrexed in the mouse brain at 30 minutes after the dose. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3∼4). *P < 0.05, compared with control.

Benzylpenicillin is a selective Oat3 substrate/inhibitor (Kikuchi et al., 2003). In our study, the possible role of Oat3 in the efflux transport of the antifolates was examined via the inhibitory effect of benzylpenicillin. As shown in Fig. 6, the elimination of both [3H]-pemetrexed and [3H]-methotrexate from the mouse brain was markedly inhibited in the presence of benzylpenicillin (100 mM in the injectate), with approximately 90% of the dose remaining in the brain 30 minutes after injection. Effect of various treatments on brain-to-blood transport of PMX and MTX are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Effect of various treatments on brain-to-blood transport of methotrexate

| [3H]-Methotrexate | Concentration in the Injectate (mM) | Concentration in the Brain (mM) | BEI (%)a | Percentage of Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (control) | — | — | 63.8 ± 5.2 | 100.0 |

| Mrp2−/− | — | — | 57.2 ± 6.0 | 90.0 |

| Bcrp1−/− | — | — | 46.4 ± 7.4b | 72.7 |

| WT + probenecid | 100 | 2.506 | 24.2 ± 8.6c | 37.9 |

| WT + benzylpenicillin | 100 | 2.506 | 13.7 ± 8.5c | 21.4 |

BEI, brain efflux index; WT, wild type.

Percentage of methotrexate eliminated from the ipsilateral cerebrum at 30 minutes.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

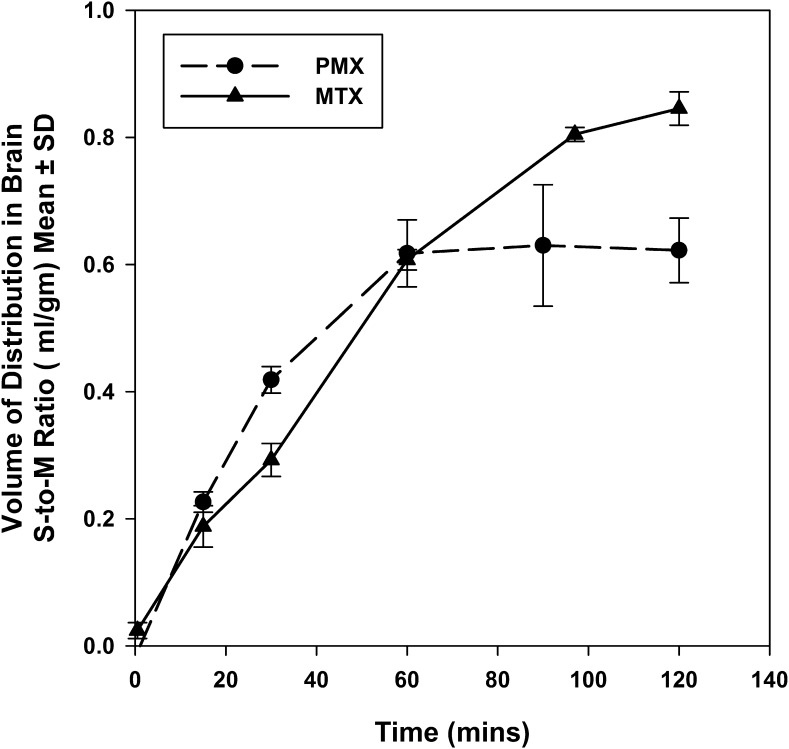

Distribution Volume of Pemetrexed and Methotrexate in Mouse Brain.

The distribution volume of PMX and MTX in the mouse brain was determined by the in vitro brain slice uptake technique. Figure 7 shows the time profiles of uptake of [3H]-pemetrexed and [3H]-methotrexate by brain slices. For both antifolates, there was no statistically significant difference in the brain distribution volume between 1-hour and 2-hour incubation, giving a steady-state brain distribution volume of 0.62 ± 0.10 ml/g brain for PMX and 0.85 ± 0.06 ml/g brain for MTX. Incorporating the elimination rate constant (keff) and brain distribution volume (Vd,brain) into eq. 3, the apparent efflux clearance (Clapp,efflux) is 11.04 μl/min·g brain for PMX and 20.23 μl/min·g brain for MTX (Table 3).

Fig. 7.

Time course of [3H]-pemetrexed and [3H]-methotrexate uptake by mouse brain slices. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3∼4).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of brain distribution of pemetrexed and methotrexate

| Clin/Cleff | keff | Vd,brain | Cleff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | ml/g brain | μl/min·g brain | ||

| Pemetrexed | 0.106a | 0.0178 ± 0.0031 | 0.62 ± 0.10 | 11.04 |

| Methotrexate | 0.05b | 0.0238 ± 0.0028 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 20.23 |

Cleff, efflux clearance; Clin, clearance into brain; Vd,brain, brain distribution volume.

Discussion

The potential use of PMX in treatment of primary and secondary brain tumors has gained more interest in recent years. MTX, a classic antifolate widely used for brain metastasis, has restricted brain penetration, thus necessitating a high systemic dose to achieve a therapeutic effect. In spite of the tremendous need to enhance the brain penetration of these antifolate agents, the mechanisms behind their limited brain distribution are still not clear. In the present study, we characterized the brain elimination kinetics of PMX and MTX, and explored the involvement of several efflux transporters in the brain distribution of the two agents.

Using the BEI method, we show that both PMX and MTX are rapidly eliminated from the brain, with their half-lives in the brain being 0.65 hours and 0.48 hours, respectively. The short retention time in the brain may be attributed to the very limited brain distribution volume. Specifically, the distribution volume (Vd) of PMX and MTX in the mouse brain, as determined by the brain slide uptake method, is close to the brain interstitial fluid space of 0.8 ml/g brain (Reinoso et al., 1997). On the other hand, efficient efflux transport may also play a role in quickly clearing these antifolate agents from the brain. We first confirmed the involvement of active efflux transport in the brain elimination of PMX. The elimination of [3H]-pemetrexed from the brain was almost completely inhibited in presence of 50 mM unlabeled PMX, suggesting that the contribution of passive diffusion to PMX brain efflux transport is very limited; active transport accounts for the majority of the total efflux.

This is consistent with physicochemical properties of PMX. As an anionic compound with a log P of −1.5, it is unlikely that PMX can cross biologic membranes readily by passive diffusion. In fact, intracellular transport of PMX is also facilitated by influx transporters, including reduced folate carrier, folate receptor, and proton-coupled folate transporter. Therefore, it is plausible that active drug transporters are required to remove PMX across lipid membranes as well as across the BBB out of the brain.

After confirming the involvement of active efflux transport in the brain distribution of PMX, we then explored the potential roles of several efflux transporters at the BBB in eliminating PMX and MTX from the brain. The first transporter we investigated is Mrp2. In a recent study, Vlaming et al. (2009) reported that Mrp2 plays an important role in determining the total body clearance of MTX. Other in vitro studies have suggested that both PMX and MTX are avid MRP2 substrates with the reported Km values being 66 µM for PMX and 480 µM for MTX (Pratt et al., 2002; El-Sheikh et al., 2007). Given the purported expression of Mrp2 at the BBB, we tested the hypothesis that Mrp2 may transport PMX and MTX at the BBB and thus limit the brain penetration of the antifolates. However, contrary to the reported in vitro findings, we did not observe any influence of Mrp2 on the efflux of either PMX or MTX from the brain. Although the functional relevance of Mrp2 in the systemic disposition of its substrates has been established via studies using Mrp2 gene knockout mice (Vlaming et al., 2006; Tian et al., 2007; Ieiri et al., 2009; Vlaming et al., 2009), the role of MRP2 in brain distribution of drugs is poorly understood. Our findings confirm this, and further research is needed to investigate the role of Mrp2 at the BBB, including additional expression studies.

In contrast to MRP2, the role of BCRP as a gatekeeper at the BBB has been well established. More importantly, BCRP also mediates the cellular transport of PMX and MTX as indicated by in vitro studies (Volk and Schneider, 2003; Li et al., 2011). The current BEI study revealed that Bcrp plays a significant role in the brain elimination of MTX, but not PMX. This is not totally unexpected because even though PMX is a structurally similar antifolate, it may possess different physiochemical properties that affect the binding affinities for the transporters. Based on the available in vitro data using in vitro vesicular uptake method, Bcrp-mediated intrinsic clearance (Vmax/Km) of MTX is about 3-fold higher than that of PMX (manuscript submitted). Therefore, the discrepancy in Bcrp-mediated efflux of the two antifolates may be explained by their different affinities for this transporter.

Considering that PMX and MTX are weak acids with an anionic charge at physiologic pH, we examined the role of organic anion transporter in brain distribution of the antifolates. We demonstrated the possible involvement of Oat3 in brain elimination of both PMX and MTX using the inhibitors probenecid and benzylpenicillin. Oat3 is localized at the abluminal membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells (Kusuhara et al., 1999; Kikuchi et al., 2003; Mori et al., 2003). It mediates the brain-to-blood transport of many hydrophilic organic anions; including indoxyl sulfate, 6-mercaptopurine, p-aminohippuric acid, benzylpenicillin, and homovanillic acid (Ohtsuki et al., 2002; Kikuchi et al., 2003; Mori et al., 2004; Kusuhara and Sugiyama, 2005). Due to the cellular localization of Oat3, it is believed that Oat3 can only transport its substrate from the brain extracellular space to brain capillary endothelial cells (Kusuhara and Sugiyama, 2005), and that another transporter is needed to remove the molecules from the endothelial cells into the bloodstream. The ABC transporter MRP4 has been shown to transport both PMX and MTX. Specifically, MRP4 mediates the transport of MTX with Km of 220 µM, and the expression of MRP4 correlates with the in vitro chemosensitivity of tumor cells to PMX (Chen et al., 2002; Hanauske et al., 2007). Given the functional role of Mrp4 at the BBB (Leggas et al., 2004; Belinsky et al., 2007), Mrp4 is likely to function at the luminal membrane cooperatively with Oat3 for the brain-to-blood transport of PMX and MTX.

In summary, the present study examined the role of several active efflux transporters at the BBB in the brain distribution of PMX and MTX. Our results show that both MTX and PMX undergo saturable efflux from brain. Of the two transporters we investigated using gene knockout mice, Mrp2 does not play a role in the brain clearance of the two antifolates, whereas Bcrp makes a significant contribution to the brain elimination of MTX but not PMX. In addition, the brain-to-blood transport of both agents was sensitive to probenecid and benzylpenicillin, suggesting the involvement of organic anion transporters, with Oat3 being a possibility. An important mechanism behind the low brain distribution of these antifolates is active efflux transport by multiple efflux systems working in tandem at the BBB. Our study has isolated several efflux systems that could be involved in the efflux of the two antifolates at the BBB.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tom Raub (Eli Lilly and Company) for providing Bcrp- and Mrp2-knockout mice, and Maureen Riedl for the help with intracerebral microinjection technique.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BCRP

breast cancer resistance protein

- BEI

brain efflux index

- Clapp, efflux

apparent efflux clearance

- CNS

central nervous system

- ECF

extracellular fluid

- keff

elimination rate constant

- MRP

multidrug resistance-associated protein

- MTX

methotrexate

- OAT

organic anion transporter

- PMX

pemetrexed

- Vd,brain

brain distribution volume

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Li, Elmquist.

Conducted experiments: Li, Agarwal.

Performed data analysis: Li, Elmquist.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Li, Agarwal, Elmquist.

Footnotes

References

- Allen DD, Smith QR. (2001) Characterization of the blood-brain barrier choline transporter using the in situ rat brain perfusion technique. J Neurochem 76:1032–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos E, Evers R, Sinkó E, Váradi A, Borst P, Sarkadi B. (2000) Interactions of the human multidrug resistance proteins MRP1 and MRP2 with organic anions. Mol Pharmacol 57:760–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky MG, Guo P, Lee K, Zhou F, Kotova E, Grinberg A, Westphal H, Shchaveleva I, Klein-Szanto A, Gallo JM, et al. (2007) Multidrug resistance protein 4 protects bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and intestine from nucleotide analogue-induced damage. Cancer Res 67:262–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley JO, Olson J, Grossman SA, He X, Weingart J, Supko JG, New Approaches to Brain Tumor Therapy (NABTT) Consortium (2009) Effect of blood brain barrier permeability in recurrent high grade gliomas on the intratumoral pharmacokinetics of methotrexate: a microdialysis study. J Neurooncol 91:51–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZS, Lee K, Walther S, Raftogianis RB, Kuwano M, Zeng H, Kruh GD. (2002) Analysis of methotrexate and folate transport by multidrug resistance protein 4 (ABCC4): MRP4 is a component of the methotrexate efflux system. Cancer Res 62:3144–3150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Chen Y, Elmquist WF. (2005) Distribution of the novel antifolate pemetrexed to the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315:222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devineni D, Klein-Szanto A, Gallo JM. (1996) In vivo microdialysis to characterize drug transport in brain tumors: analysis of methotrexate uptake in rat glioma-2 (RG-2)-bearing rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 38:499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh AA, van den Heuvel JJ, Koenderink JB, Russel FG. (2007) Interaction of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with multidrug resistance protein (MRP) 2/ABCC2- and MRP4/ABCC4-mediated methotrexate transport. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner ER, Carson KA, Grossman SA, Batchelor TT. (2008) Long-term outcome in PCNSL patients treated with high-dose methotrexate and deferred radiation. Neurology 70:401–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden PL, Pollack GM. (2003) Blood-brain barrier efflux transport. J Pharm Sci 92:1739–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimeur A, Conseil G, Deeley RG, Cole SP. (2004) The MRP-related and BCRP/ABCG2 multidrug resistance proteins: biology, substrate specificity and regulation. Curr Drug Metab 5:21–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanauske AR, Eismann U, Oberschmidt O, Pospisil H, Hoffmann S, Hanauske-Abel H, Ma D, Chen V, Paoletti P, Niyikiza C. (2007) In vitro chemosensitivity of freshly explanted tumor cells to pemetrexed is correlated with target gene expression. Invest New Drugs 25:417–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieiri I, Higuchi S, Sugiyama Y. (2009) Genetic polymorphisms of uptake (OATP1B1, 1B3) and efflux (MRP2, BCRP) transporters: implications for inter-individual differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of statins and other clinically relevant drugs. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 5:703–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T. (2006) Functional characterization of the brain-to-blood efflux clearance of human amyloid-beta peptide (1-40) across the rat blood-brain barrier. Neurosci Res 56:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakee A, Takanaga H, Hosoya K, Sugiyama Y, Terasaki T. (2002) In vivo evidence for brain-to-blood efflux transport of valproic acid across the blood-brain barrier. Microvasc Res 63:233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakee A, Terasaki T, Sugiyama Y. (1996) Brain efflux index as a novel method of analyzing efflux transport at the blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277:1550–1559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi R, Kusuhara H, Sugiyama D, Sugiyama Y. (2003) Contribution of organic anion transporter 3 (Slc22a8) to the elimination of p-aminohippuric acid and benzylpenicillin across the blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306:51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T, Recht L. (2006) Optimizing therapy for patients with brain metastases. Semin Oncol 33:299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara H, Sekine T, Utsunomiya-Tate N, Tsuda M, Kojima R, Cha SH, Sugiyama Y, Kanai Y, Endou H. (1999) Molecular cloning and characterization of a new multispecific organic anion transporter from rat brain. J Biol Chem 274:13675–13680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y. (2005) Active efflux across the blood-brain barrier: role of the solute carrier family. NeuroRx 2:73–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara H, Suzuki H, Terasaki T, Kakee A, Lemaire M, Sugiyama Y. (1997) P-Glycoprotein mediates the efflux of quinidine across the blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283:574–580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara H, Terasaki T, Sugiyama Y. (2003) Brain efflux index method. Characterization of efflux transport across the blood-brain barrier. Methods Mol Med 89:219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggas M, Adachi M, Scheffer GL, Sun D, Wielinga P, Du G, Mercer KE, Zhuang Y, Panetta JC, Johnston B, et al. (2004) Mrp4 confers resistance to topotecan and protects the brain from chemotherapy. Mol Cell Biol 24:7612–7621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Sham YY, Bikadi Z, Elmquist WF. (2011) pH-Dependent transport of pemetrexed by breast cancer resistance protein. Drug Metab Dispos 39:1478–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DS, Nobmann SN, Gutmann H, Toeroek M, Drewe J, Fricker G. (2000) Xenobiotic transport across isolated brain microvessels studied by confocal microscopy. Mol Pharmacol 58:1357–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Ohtsuki S, Takanaga H, Kikkawa T, Kang YS, Terasaki T. (2004) Organic anion transporter 3 is involved in the brain-to-blood efflux transport of thiopurine nucleobase analogs. J Neurochem 90:931–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Takanaga H, Ohtsuki S, Deguchi T, Kang YS, Hosoya K, Terasaki T. (2003) Rat organic anion transporter 3 (rOAT3) is responsible for brain-to-blood efflux of homovanillic acid at the abluminal membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23:432–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motl S, Zhuang Y, Waters CM, Stewart CF. (2006) Pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of CNS tumours. Clin Pharmacokinet 45:871–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY, Claus EB. (2011) Survival among patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma, 1973-2004. J Neurooncol 101:487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki S, Asaba H, Takanaga H, Deguchi T, Hosoya K, Otagiri M, Terasaki T. (2002) Role of blood-brain barrier organic anion transporter 3 (OAT3) in the efflux of indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin: its involvement in neurotransmitter metabolite clearance from the brain. J Neurochem 83:57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. (1999) Blood-brain barrier biology and methodology. J Neurovirol 5:556–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. (2001) Crossing the blood-brain barrier: are we getting it right? Drug Discov Today 6:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt SE, Emerick RM, Horwitz L, Gallery M, Lesoon A, Jink S, Chen VJ, Dantzig AH. (2002) Multidrug resistance proteins (MRP) 2 and 5 transport and confer resistance to Alimta. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res 43: 782 [Google Scholar]

- Reinoso RF, Telfer BA, Rowland M. (1997) Tissue water content in rats measured by desiccation. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 38:87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama D, Kusuhara H, Shitara Y, Abe T, Meier PJ, Sekine T, Endou H, Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y. (2001) Characterization of the efflux transport of 17β-estradiol-D-17β-glucuronide from the brain across the blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298:316–322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Zaima C, Moriki Y, Fukami T, Tomono K. (2007) P-glycoprotein mediates brain-to-blood efflux transport of buprenorphine across the blood-brain barrier. J Drug Target 15:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasawa K, Terasaki T, Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y. (1997) In vivo evidence for carrier-mediated efflux transport of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine and 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine across the blood-brain barrier via a probenecid-sensitive transport system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 281:369–375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Li J, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Bridges AS, Zhang P, Patel NJ, Raub TJ, Pollack GM, Brouwer KL. (2007) Roles of P-glycoprotein, Bcrp, and Mrp2 in biliary excretion of spiramycin in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3230–3234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart BL, Kim RB. (2009) Blood-brain barrier transporters and response to CNS-active drugs. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 65:1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaming ML, Mohrmann K, Wagenaar E, de Waart DR, Elferink RP, Lagas JS, van Tellingen O, Vainchtein LD, Rosing H, Beijnen JH, et al. (2006) Carcinogen and anticancer drug transport by Mrp2 in vivo: studies using Mrp2 (Abcc2) knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318:319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaming ML, Pala Z, van Esch A, Wagenaar E, de Waart DR, van de Wetering K, van der Kruijssen CM, Oude Elferink RP, van Tellingen O, Schinkel AH. (2009) Functionally overlapping roles of Abcg2 (Bcrp1) and Abcc2 (Mrp2) in the elimination of methotrexate and its main toxic metabolite 7-hydroxymethotrexate in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 15:3084–3093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk EL, Schneider E. (2003) Wild-type breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) is a methotrexate polyglutamate transporter. Cancer Res 63:5538–5543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]