Abstract

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a fetal complication of pregnancy epidemiologically linked to cardiovascular disease in the newborn later in life. However, the mechanism is poorly understood with very little research on the vascular structure and function during development in healthy and IUGR neonates. Previously, we found vascular remodeling and increased stiffness in the carotid and umbilical arteries, but here we examine the remodeling and biomechanics in the larger vessels more proximal to the heart. To study this question, thoracic and abdominal aortas were collected from a sheep model of placental insufficiency IUGR (PI-IUGR) due to exposure to elevated ambient temperatures. Aortas from control (n = 12) and PI-IUGR fetuses (n = 10) were analyzed for functional biomechanics and structural remodeling. PI-IUGR aortas had a significant increase in stiffness (P < 0.05), increased collagen content (P < 0.05), and decreased sulfated glycosaminoglycan content (P < 0.05). Our derived constitutive model from experimental data related increased stiffness to reorganization changes of increased alignment angle of collagen fibers and increased elastin (P < 0.05) in the thoracic aorta and increased concentration of collagen fibers in the abdominal aorta toward the circumferential direction verified through use of histological techniques. This fetal vascular remodeling in PI-IUGR may set the stage for possible altered growth and development and help to explain the pathophysiology of adult cardiovascular disease in previously IUGR individuals.

Keywords: fetal programming, biomechanics, vascular remodeling, collagen, elastin

intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a clinical complication that places the fetus and newborn infant at significant risk for morbidity and mortality (8, 19, 29). Epidemiological studies have reported long-term chronic complications in the fetus such as adult hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and diabetes (2, 3, 18, 28). Currently, researchers have hypothesized the mechanism of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is arterial dysfunction characterized by “premature aging” (27). This theory is based upon extracellular matrix (ECM) formation during the fetal and neonatal period with protein depositions of collagen and elastin, the largest contributors to vessel compliance, highest during this developmental window (9, 15, 42, 43) and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), important proteins in vessel ECM development and viscoelastic strength, also deposited during this period (13, 35). Disruption of the synthesis and deposition of vascular collagen, elastin, and GAGs in utero is thought to be a major mechanism in adult CVD in previously IUGR individuals.

Hemodynamic stress in adult arteries has been shown as an important modulator in vascular ECM composition and stiffness (12, 20). The fetal cardiovascular system in utero receives growth and development signaling from hemodynamic forces during the fetal and neonatal period (6, 7) and is highly susceptible to abnormal vascular constitutive remodeling due to abnormal hemodynamic stress (1). Hypoxic IUGR fetuses redistribute cardiac output altering the hemodynamics forces along the arterial tree (5). Changes in the thoracic aorta and abdominal aorta in the healthy neonatal lamb between 131 days gestation and 2–3 wk postpartum show that hemodynamics play a critical role in determining arterial structure (6). In IUGR newborns, a sustained change in hemodynamics has been shown through increased aortic pulse wave velocity indicating vascular stiffening in low birth weight babies as young children (31). Proximal aortic vascular stiffening is thought to be an important contributor to the progression of CVD (22, 36, 37).

Our group has used a fetal sheep model of placental insufficiency IUGR (PI-IUGR) that replicates many of the key features of human IUGR to study the pathogenesis of placental insufficiency complications (5). The sheep model of PI-IUGR has proven a useful model for studying underlying mechanisms in human PI-IUGR and has played an integral part in our current understanding of both normal and complicated pregnancies (4). Previously, we showed carotid and umbilical stiffening through different remodeling mechanisms in smaller more muscular arteries (10). However, the extent of proximal remodeling in the large elastic arteries has yet to be determined. In adolescents and adults, increased stiffness in the proximal large elastic arteries is a significant contributor to the progression of CVD increasing vascular resistance and heart afterloading (22, 36, 37).

Therefore, our goal was to test the biomechanics of the great elastic vessels, the thoracic and abdominal aortas, and measure the wall composition and structural organization to assess the degree and site-specific changes in proximal remodeling. We hypothesized PI-IUGR thoracic and abdominal aortas would exhibit increased stiffness due to increased collagen content and reorganized structure compared with controls. To test this hypothesis, we used aortas harvested from near-term control and PI-IUGR animals and assessed passive compliance, biochemical composition, and histomorphological structure to model the stiffening mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

This study was approved by the University of Colorado Denver Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed at the Perinatal Research Center, an accredited facility by the National Institutes of Health, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. A total of 22 mixed-breed Columbia-Rambouillet ewes with time-dated singleton pregnancies were used for this study. Ten ewes were housed in an environmental chamber for maternal hyperthermic exposure (40°C for 12 h; 35° for 12 h) for 80 days beginning at 35 days of gestational age (term = 147 days) as previously described (4, 5, 10, 32, 33). Following the hyperthermic exposure, ewes were housed in a normothermic environment (20°C) for the remainder of the study. Twelve control ewes were housed in a normothermic environment for the duration of the study.

Mechanical testing.

Fetal and placental weights and lengths were obtained and recorded as previously described (10, 11). The thoracic aortas (control n = 11; PI-IUGR n = 10) were dissected from the base of the aortic arch to the diaphragm. The abdominal aorta (control n = 11; PI-IUGR n = 9) was dissected from the top of the diaphragm to the branches of the iliac and umbilical arteries. The aortas were stored in calcium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C until testing.

Vessel morphology was assessed before testing by measuring a stress-free 2-mm-long ring portion of the dissected arteries measured for thickness and inner diameter optically. The dissected aortas were tested for stiffness using transmural pressure and diameter as previously described (10, 11). In brief, the aorta was cannulated and sutured into a custom arteriography chamber and tested for passive compliance measuring transmural pressure, axial stretch, and vessel diameter. Aortas were tested for compliance using the ISO 7198.8.6 standard for the determination of a pressurized diameter. Aortas were inflated from 5 to 10–200 mmHg in 10-mmHg increments and from 200 to 300 mmHg in 20-mmHg increments at prescribed axial stretches from 0 to 40% in 10% increments. Following mechanical testing, segments were collected and frozen for biochemical assay or fixed for histological examination as described below.

In vitro biochemical assay.

An ∼20-mg portion/test sample was lyophilized and weighed for dry mass. The dried tissue was hydrolyzed in 200 μl of 6 M HCl and dried using a speedvac. The amounts of elastin and collagen in the ECM were quantified using standard measurements of tissue desmosine and hydroxyproline content, respectively (38, 39). An additional ∼20-mg portion/test sample was dried and weighed for dry mass. Sulfated GAG content was measured using a standard dimethylmethylene assay with chondroitin-6-sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as the standard (14).

Histology.

Mechanical test samples of control and PI-IUGR aortas were processed for histology. The histological samples were formalin fixed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm with each artery stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson (VVG) for collagen and elastin content and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for general structure and cell number. Three representative fixed test samples of control and PI-IUGR thoracic and abdominal aortas were processed for imaging. Samples were rehydrated using PBS and then dissected and oriented for imaging in the circumferential-axial plane and imaged using laser confocal second harmonic generation (SHG) to visualize collagen and elastin content as previously described (11). Images were quantified for collagen fiber orientation and dispersion using a previously validated custom-written ImageJ analysis macro OrientationJ (30). An effective fiber angle was determined through a weighted mean and dispersion through the standard deviation from the mean.

Data analysis.

The aortic walls were analyzed using the Gasser et al. constitutive model as previously described (11, 17). Experimental arterial walls were modeled as single layer fiber reinforced isochoric hyperelastic material. A strain energy function constitutively relates the stress required to deform a fiber composite hyperelastic artery. It is composed of an isotropic function (ΨIsotropic) that describes the ground substance and elastin dominant portion of the vessel low load response and an anisotropic function (ΨAnisotropic) that accounts for collagen fiber orientation and engagement at higher loads with an exponential increase in material stiffness at high strains as collagen recruitment takes over the load response.

The isotropic function (ΨIsotropic) employs a neo-Hooken model that describes the behavior of isotropic rubber-like materials. In the circumferential and axial planes this term becomes:

| (1) |

where Î1 is the first invariant, c is a fitting constant, and λθ and λz are the stretches in the circumferential and axial directions, respectively. The constant c is related to the shear modulus of the tissue. The anisotropic function (ΨAnisotropic) describes the exponential increase in load as collagen engagement begins, and the strain energy function is appropriately in exponential form:

| (2) |

in which the constant k1 ≥ 0 is a stress-like parameter, k2 is dimensionless, κ describes the fiber dispersion (κ = 0 fibers ideally anisotropically aligned, κ = 1/3 fibers isotropically distributed), and the collagen fiber angle, γ. The invariant, Î4, characterizes the constitutive response of the fibers to mechanical loading.

To model the experimental response, the pressurization of a thin-walled tube was considered with an initial wall thickness (H) and mean vessel radius (R) axially stretched across the experimentally prescribed conditions with no applied axial load and an internal pressure, pi, resulting in boundary conditions described in the axial and circumferential directions (17):

| (3) |

where fz and fθ denote the axial and circumferential functions. Equations 3 define a system of nonlinear equations that can be solved numerically for a prescribed internal pressure, pi.

The hyperelastic constitutive model was fit to experimental data by optimizing the correspondence between model predicted behavior and experimental behavior provided from the experimental pressure-diameter tests, by minimizing the stress-based nonlinear error function

| (4) |

where n is the number of experimental data points and the weighting factors are w1 and w2. Error function minimization was performed using Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) across a continuous spectrum of circumferential stretches and at five discrete axial stretches, corresponding to the available experimental data. Constitutive parameters were found for both the thoracic and abdominal aorta across all sets of data minimizing the error function.

The degree of agreement between the experimental data and the constitutive model was assessed by a goodness of fit test. The F distribution (F) was measured based upon the value of the residual sum of the squares (Res SS) of the considered constitutive model for the individual experimental data points (yi) and the residual points (ŷi) and defined

| (5) |

where n is the number of considered data points, q is the number of parameters of Ψ, and n-q is the number of degrees of freedom. The regression sum of the squares (Reg SS) is the sum of all the wall stresses for each data point divided by the number of all data points.

RESULTS

Anatomical findings.

PI-IUGR fetuses exhibited a 40% reduction in fetal weight (P < 0.05), a 33% reduction in placental weight (P < 0.05), and a 14% reduction in crown to rump length (P < 0.05) compared with the control fetuses (Table 1). The PI-IUGR thoracic aorta morphology exhibited no change in the inner diameter and a reduction of the wall thickness by 30% (P < 0.05) compared with the control, increasing the ratio of inner diameter to wall thickness. Abdominal aorta morphology in PI-IUGR had a reduced inner diameter by 18% (P < 0.05) and wall thickness by 19% (P < 0.05), maintaining the ratio of inner diameter to wall thickness. Wall composition measured by biochemical assays demonstrated vessel-specific changes. In the thoracic aorta, the collagen (hydroxyproline) and elastin (desmosine) content increased by 24% (P < 0.05) and 30% (P < 0.05), respectively, whereas sulfated GAG content was decreased by 33% (P < 0.05) in PI-IUGR (Table 1). The abdominal aorta contained increased collagen by 30% (P < 0.05) and decreased sulfated GAG by 38% (P < 0.05) in PI-IUGR.

Table 1.

Necropsy data

| Control (n = 12) | PI-IUGR (n = 10) | Change, % | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necropsy data | ||||

| Fetal wt, g | 3,391.4 ± 228.0 | 2,044.0 ± 163.8 | ↓40% | <0.001 |

| Placental wt, g | 324.8 ± 34.6 | 218.9 ± 17.8 | ↓33% | 0.03* |

| Age at Necropsy, days | 134 ± 1 | 133 ± 1 | 0.7 | |

| Crown to rump length, mm | 468 ± 13 | 403 ± 9 | ↓14% | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female n (%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (45%) | ||

| Male n (%) | 8 (67%) | 6 (55%) | ||

| Morphology | ||||

| Thoracic | ||||

| ID, mm | 3.98 ± 0.23 | 3.52 ± 0.16 | 0.21 | |

| Thickness, mm | 1.99 ± 0.07 | 1.38 ± 0.08 | ↓30% | <0.001 |

| ID-to-thickness ratio | 1.93 ± 0.14 | 2.61 ± 0.19 | ↑35% | 0.008 |

| Cross-sectional area, mm2 | 37.6 ± 2.2 | 21.6 ± 2.1 | ↓43% | <0.001 |

| Abdominal | ||||

| ID, mm | 4.58 ± 0.81 | 3.75 ± 0.16 | ↓18% | 0.01 |

| Thickness, mm | 0.67 ± 0.13 | 0.54 ± 0.09 | ↓19% | 0.02 |

| ID-to-thickness ratio | 7.08 ± 0.63 | 7.12 ± 0.64 | 0.96 | |

| Cross-sectional area, mm2 | 11.1 ± 2.8 | 7.3 ± 1.3 | ↓34% | <0.01 |

| Biochemical composition | ||||

| Thoracic | ||||

| Hydroxyproline, μg/mg dry tissue | 54.0 ± 3.3 | 66.8 ± 2.9 | ↑24% | 0.01 |

| Desmosine, μg/mg dry tissue | 3.00 ± 0.39 | 3.90 ± 0.15 | ↑30% | 0.05 |

| sGAG, μg/mg dry tissue | 32.9 ± 1.7 | 21.9 ± 1.3 | ↓33% | <0.001 |

| Abdominal | ||||

| Hydroxyproline, μg/mg dry tissue | 78.0 ± 6.0 | 101.4 ± 6.0 | ↑30% | 0.010 |

| Desmosine, μg/mg dry tissue | 2.80 ± 0.31 | 2.94 ± 0.39 | 0.78 | |

| sGAG, μg/mg dry tissue | 28.4 ± 2.1 | 17.5 ± 1.1 | ↓38% | <0.001 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of ewes. ID, inner diameter; sGAG, sulfated glycosaminoglycans; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase. Animals show reduced fetal size in the placental insufficiency intrauterine growth restriction (PI-IUGR) model. PI-IUGR vessels have reduced geometry and remodeled wall composition.

Mann-Whitney Nonparametric test.

Biomechanical findings.

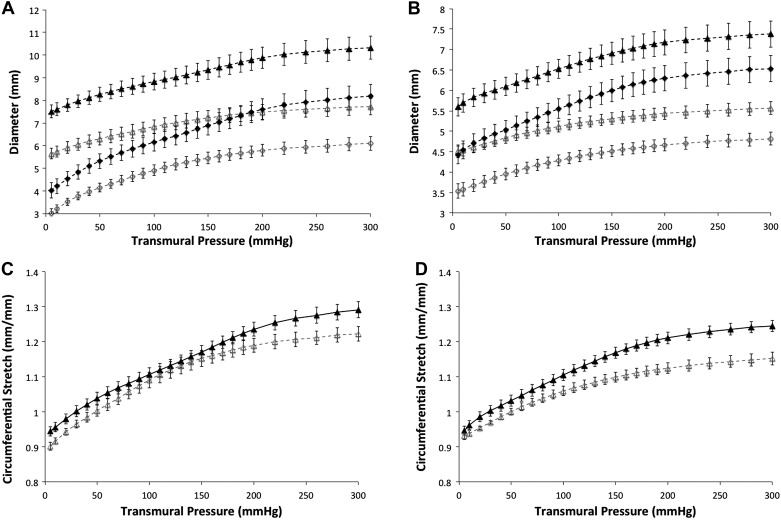

The thoracic aorta exhibited reduced outer diameter, inner diameter, and wall thickness across all transmural pressures (5–300 mmHg) in PI-IUGR (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Similarly, the abdominal aorta had decreased outer and inner diameters (P < 0.05) across all transmural pressures (5–300 mmHg) in PI-IUGR but retained a mean wall thickness similar to the controls (P = 0.50). Both thoracic and abdominal aortas showed increased stiffness demonstrated by the reduced circumferential stretch in response to transmural pressure in PI-IUGR (Fig. 1). In PI-IUGR, the thoracic aorta showed an increased stiffness at transmural pressures between 5–20 and 190–300 mmHg (P < 0.05), whereas the abdominal aorta demonstrated an increased stiffness at transmural pressures between 100 and 300 mmHg in PI-IUGR (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

A and B: pressure vs. diameter for control (closed symbols) and placental insufficiency IUGR (PI-IUGR, open symbols) at a stretch of 1.2. Thoracic aorta (A) has a significantly reduced outer diameter (triangles), inner diameter (diamonds), and wall thickness from 5 to 300 mmHg (P < 0.05). Abdominal aorta (B) has a significantly reduced outer diameter (triangles) and inner diameter (diamonds) from 5 to 300 mmHg (P < 0.05). C and D: pressure vs. circumferential stretch for control (closed triangles) and PI-IUGR (open triangles) at a stretch of 1.2. Thoracic aorta (C) is significantly different at pressures between 5–20 and 190–300 mmHg (P < 0.05). Abdominal aorta (D) is significantly different at pressures between 100 and 300 mmHg (P < 0.05).

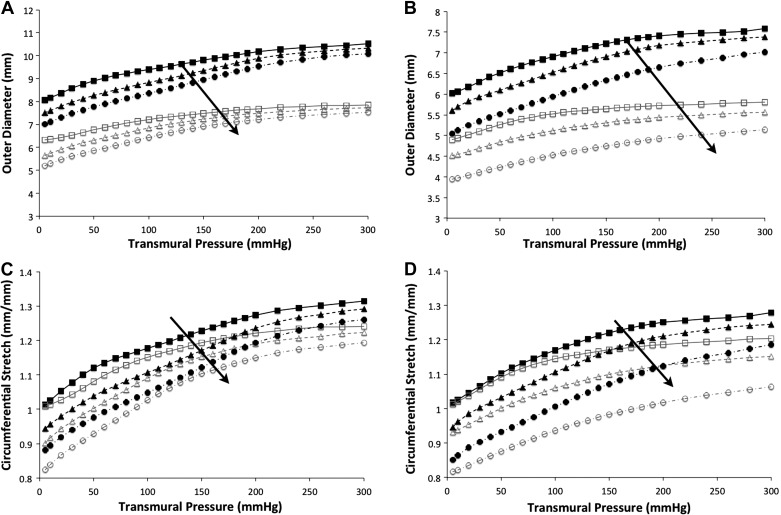

Figure 2 shows the stiffening trend with reduced outer diameter and circumferential stretch as axial stretches were applied from 1.0 to 1.2 and finally to 1.4. Across an axial stress step, the abdominal aorta PI-IUGR artery increases in stiffness much more than the control artery. As axial stretch increased, a reduction of the mean thoracic aorta outer diameter and circumferential stretch was observed of 5% (range = 2–7%) in control arteries and 5% (range = 2–10%) in PI-IUGR arteries. In the abdominal aorta, the mean outer diameter and circumferential stretch were reduced, varying from 6% (range = 2–7%) in control arteries and 8% (range = 4–10%) in PI-IUGR as axial stretch was increased from 1.0 to 1.2. As axial stretch was increased from 1.2 to 1.4 in the abdominal aorta, the mean outer diameter and circumferential stretch were reduced, varying from 8% (range = 5–10%) in the control arteries and 11% (range = 8–12%) in the PI-IUGR arteries. The PI-IUGR abdominal aortas had an increased stiffening as shown in reduced circumferential stretch (P < 0.05) due to applied axial stretching compared with the control arteries.

Fig. 2.

A and B: representative pressure vs. outer diameter for thoracic aorta (A) and abdominal aorta (B) with axial stretches of 1.0, 1.2, and 1.4 (squares, triangles, and circles, respectively). Closed symbols, control; open symbols, PI-IUGR. Curves shift downward showing reduced diameter with increased stretching as indicated by the arrows. C and D: representative circumferential stretch vs. pressure for thoracic aorta (C) and abdominal aorta (D) with axial stretches of 1.0, 1.2, and 1.4 (squares, triangles, and circles, respectively). Curves shift downward with increasing stretches as indicated by the arrows showing increased stiffness.

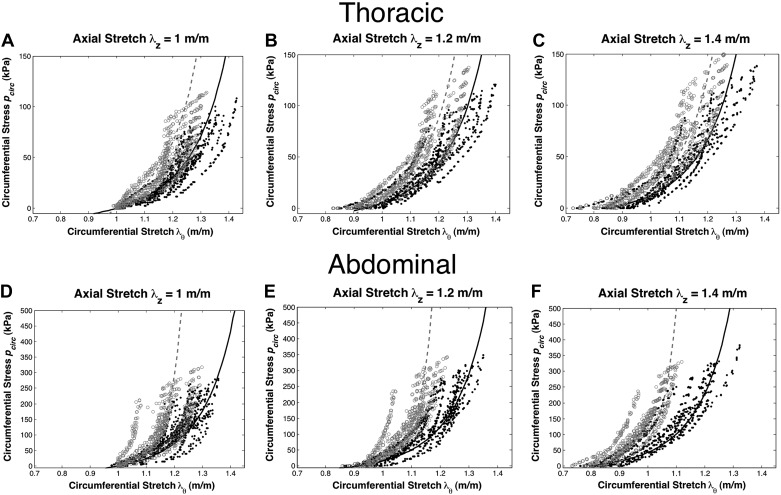

The constitutive model response (curves) was obtained from a fit to the experimental data (points) of circumferential stretch vs. circumferential stress shown across axial stretches of 1.0, 1.2, and 1.4 for the thoracic and abdominal aortas (Fig. 3). The goodness of fit values for the thoracic aorta obtained from the error for the F distribution were 3.6 × 10−6 and 4.3 × 10−6 for the control and PI-IUGR arteries, respectively, whereas for the abdominal aorta these values were 9.4 × 10−7 and 4.4 × 10−6 for the control and PI-IUGR arteries, respectively. These minimal F distribution errors indicate the constitutive model fit parameters are statistically significant (P < 0.05). The constitutive parameters c, k1, k2, γ, and κ based upon macroscopic response are summarized in Table 2. The thoracic aorta showed an increase in the isotropic and anisotropic contribution concomitant to collagen fibers aligned circumferentially (γ) creating stiffer vessels in PI-IUGR. The abdominal aorta exhibited increased anisotropic contribution with more circumferentially oriented collagen fibers (κ) stiffening in PI-IUGR vessels.

Fig. 3.

Experimental data for control (●) and PI-IUGR (○) with experimental fit for control (solid line) and PI-IUGR (broken line). Axial stretches of 1.0 (A), 1.2 (B), and 1.4 (C) for the thoracic aorta and axial stretches of 1.0 (D), 1.2 (E), and 1.4 (F) for the abdominal aorta.

Table 2.

Data fit coefficients using the anisotropic hyperelastic model of the thoracic aorta and the abdominal aorta in control and IUGR near-term fetuses

| c, kPa | k1, kPa | k2 | γ, degree | κ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoracic | |||||

| Control | 4.7 | 26.5 | 2.2 | 23.4 | 0.118 |

| PI-IUGR | 25.3 | 34.1 | 4.3 | 15.7 | 0.126 |

| Abdominal | |||||

| Control | 3.1 | 84.3 | 2.9 | 29.5 | 0.121 |

| PI-IUGR | 1.0 | 94.5 | 15.9 | 27.4 | 0.085 |

IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; c, fitting constant; k1 stress-like parameter constant; k2, dimensionless constant; γ, collagen fiber angle; κ, fiber dispersion.

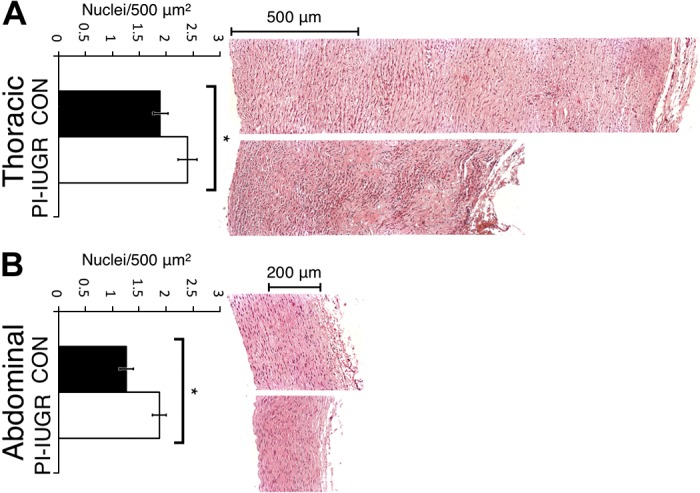

Histomorphology.

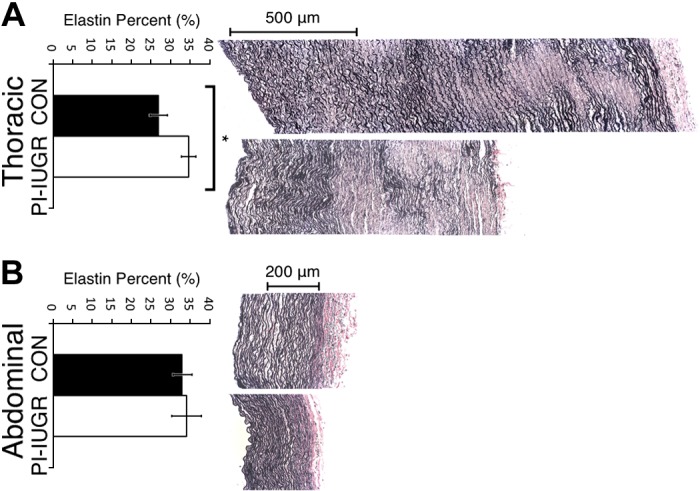

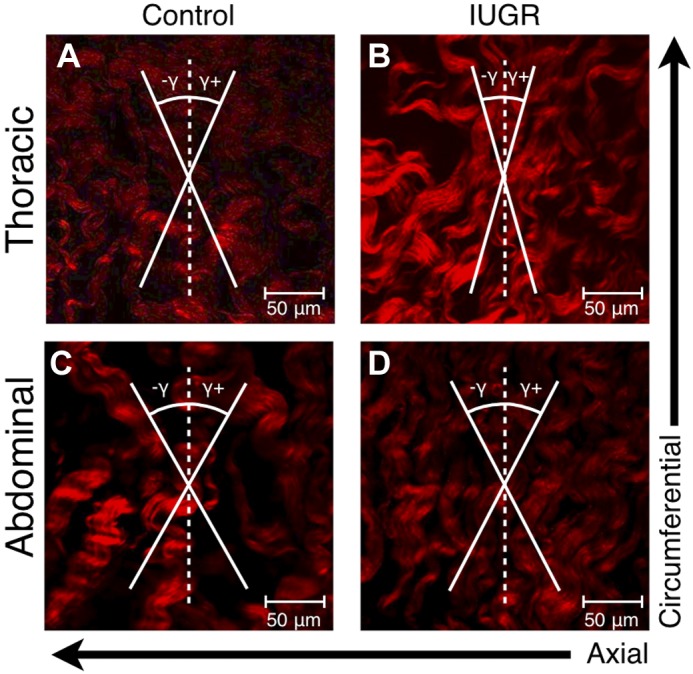

Histology samples were examined for both morphological quantitative and qualitative differences. H&E image analysis from thoracic and abdominal aortas showed an increase in cellular density in the PI-IUGR vessels (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4). Changes in cellular shape and distribution were also noted between the two groups. PI-IUGR vessels exhibited densely clustered cells near the external elastic lamina and adventitia. Histomorphometric analysis of VVG-stained sections in the thoracic aorta showed significant increased elastin content in PI-IUGR (P < 0.5) (Fig. 5). However, histomorphometric analysis of the abdominal aorta showed no significant changes in elastin content. Observed qualitative differences were noted: elastic lamellae (black) structure in the PI-IUGR appeared more globular and less organized than the control samples that exhibited concentric elastic bands. The predicted fiber angle values (γ) and fiber dispersion (κ) were validated using SHG (Fig. 6). Thoracic and abdominal aorta images confirmed a strong correlation for fiber angle and fiber dispersion compared with the predictive constitutive model parameters.

Fig. 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histology and analysis. H&E-stained cross sections for thoracic aorta (A) and abdominal aorta (B). Top in A and B: representative control (CON) images. Bottom in A and B: representative PI-IUGR images. Quantification for no. of nuclei/500 mm2 for both the thoracic aorta and abdominal aorta showed increased cell nuclei per area in PI-IUGR (*P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Verhoeff-van Gieson (VVG) histology and analysis. VVG-stained cross sections for thoracic aorta (A) and abdominal aorta (B). Top in A and B: representative control images. Bottom in A and B: representative PI-IUGR images. Elastin area fraction measures the collagen-to-elastin ratio. The thoracic aorta (A) showed increased area of elastin to total arterial wall area in PI-IUGR (*P < 0.05), but the abdominal aorta (B) showed no significant changes in area of elastin to total wall area in PI-IUGR. Qualitative reorganization of collagen (red) and elastin (black) was noted with elastic lamellae appearing more globular and less organized in PI-IUGR compared with the well-formed concentric elastic bands in the control.

Fig. 6.

Experimental second harmonic generation image measurements showed a fiber angle (γ) 26.3 ± 3.6° and dispersion of 0.092 for control thoracic aortas (A) and a fiber angle 12.4 ± 3.4° and dispersion of 0.091 for the PI-IUGR thoracic aortas (B) matching predicted values. Image measurements showed a fiber angle 26.8 ± 4.0° and dispersion of 0.102 for control abdominal aortas (C) and a fiber angle 28.7 ± 2.0° and dispersion of 0.051 for the PI-IUGR abdominal aortas (D) matching predicted values.

DISCUSSION

Our major findings showed that the proximal, elastic arteries of the thoracic and abdominal aortas stiffen in response to PI-IUGR, while displaying different structural etiologies. The PI-IUGR thoracic aorta had a reduction in sulfated GAG content, increases in both collagen and elastin content, and increased collagen fiber alignment (γ) in the circumferential direction. The increased elastin and collagen contributed to isotropic and anisotropic stiffening, respectively. The PI-IUGR abdominal aorta had a reduction in sulfated GAG content, an increase in collagen, and decreased collagen fiber dispersion (κ) creating more aligned anisotropic fibers, increasing circumferential stiffness. At the end of gestation, the extracellular content and organization is remodeled in the PI-IUGR fetal sheep systemic vasculature increasing aortic stiffness.

These findings are important in understanding changes in the functional response of stiffened proximal vessels under diseased conditions, namely a reduction in the functional elastic reservoir, due to ECM remodeling. This important change is an often neglected contributor compared with the well-known increases in resistance and altered hemodynamics in the PI-IUGR model. Vascular remodeling indicates vascular dysfunction in PI-IUGR altering systemic cardiovascular growth and development. The increase in systemic stiffening represents a novel finding and possible mechanism of increased CVD of IUGR infants as adults. This work demonstrates that the intrauterine stress environment shapes vascular growth and development and can be altered in response to maternal disease. Building upon our previous work, we show that increases in stiffness occur along the arterial tree, but the pathophysiological remodeling mechanism differs with location, which may be due to the complex changes in hemodynamic blood flows to organ beds in PI-IUGR. Through the PI-IUGR model, our work moves toward understanding preclinical molecular events that may enhance the ability to detect patient risk and has the unique benefit of determining early life influences on later cardiovascular health.

During the neonatal transition, the thoracic and abdominal aortas develop differently in response to the changes in hemodynamic stress (23, 24). Our previous work showed that remodeling occurs differently in the carotid and umbilical arteries concomitant with increased stiffness with increases in collagen in the carotid artery and decreased sulfated GAGs in the umbilical artery in PI-IUGR (10, 11). This work further examines the role of PI-IUGR alterations in systemic vascular development in the proximal aortas. CVD is thought to start vascular remodeling with changes in resistance at the organ level and progress to the proximal artery stiffness, which has recently received interest as an important indicator of morbidity and mortality (36). The work presented here shows that newborns with IUGR are at risk for increased proximal artery stiffness that will more directly affect left heart afterload and systemic hemodynamics than the carotid stiffness. Hypoxia has been shown to be a strong modulator of structural vascular remodeling in fetal sheep thoracic aorta resulting in increased collagen content, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1), matrix metalloproteinases, α-actin, and E-selectin and reduced elastin content (41). Remodeling in fetal aortic development due to IUGR stress in utero leads to structural remodeling resulting in aortic stiffening in the guinea pig as an adult (40). Therefore, both hemodynamics and oxygen tension appear to be important modulators of fetal vascular development and that development clearly has far-reaching implications beyond gestation.

Altered hemodynamics, increases in flow and pressure with the intrinsic stretch, have been shown to increase vascular stiffening and cause vascular remodeling in the mature vasculature (12, 16, 20). The mechanotransduction pathways for the vascular remodeling have been well established in the adult where small increases in flow have been observed to stimulate production of nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin, nitric oxide synthase, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGR)-A, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-1, FGF-2, TGF-β, interleukin-1 and -6, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 while downregulating vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (21). Small increases in pressure are also observed to stimulate the production of PDGR-A, PDGF-B, FGF-1, FGF-2, and thromboxane (21). However, large pathological increases in hemodynamic flow and pressure in the mature vasculature have been shown to disrupt production of biomolecules of vasoactive mediators, angiogenesis, and inflammation (25, 26). These mechanisms of hemodynamic stress are relatively well established in the mature vasculature, but have received little attention in the fetal and neonatal developing vasculature. While the possible mechanisms outlined were not examined in the current study, it is probable that these factors play a role in the different vascular mechanical stiffening observed along the vascular tree. Our group has shown impaired endothelial function in the IUGR pulmonary arteries with disruption in the NO, VEGF, and protein kinase B production in IUGR (34). With preliminary data gathered in ongoing studies, we speculate that PI-IUGR may lead to systemic artery endothelial cell dysfunction as measured through decreased growth, migration, tube formation, and loss of a highly proliferative population. We also have preliminary data of disrupted myogenic tone concomitant to vascular stiffening. Furthermore, our current in vitro studies indicate that hemodynamics may alter fetal endothelial cell phenotype by altering vasoactive mediators, angiogenic, inflammatory, and ECM gene expression. Future studies may include coherent analysis of biomechanical and biomolecular factors to identify key pathways in systemic vascular remodeling in IUGR.

In addition, several potential limitations in our study must be acknowledged. First, in this study we examined the role of PI-IUGR in the near-term time point. This work has important consequences for understanding vascular dysfunction and disease that may be present in the IUGR newborn. Furthermore, we hypothesize that intrauterine stress has long-term consequences based upon the Barker hypothesis literature, and acknowledge that exploration of this hypothesis will require future work in understanding the sequelae of CVD following intrauterine stress. By studying the end of gestation, the disease initiation and progression of vascular disease is not clearly understood, but this work represents an initial study into an underlying mechanism that altered vascular development and provides a potentially novel therapeutic target in the newborn treating vascular remodeling before the onset of CVD. Also, we present here the static and passive stiffness. Further studies should examine the dynamic compliance and vasoactive tone; however, static passive tests for compliance are the gold standard and basis for relating anatomical structure and physiological function. Finally, this work represents an investigation of the role of PI-IUGR in vascular remodeling. The underlying cellular and extracellular mechanisms of fetal vascular remodeling are still not understood and will require more research to understand the vascular pathogenesis in PI-IUGR.

Placental insufficiency in fetal sheep creates increased vascular stiffening through remodeling at the end of gestation, which in turn sets the stage for possible altered vascular growth and development. Changes in fetal development in response to placental insufficiency may be a mechanism for CVD later in life, the Barker hypothesis (2). The observed vascular changes in this study help define the pathogenic link between placental insufficiency and adult hypertension. Timely clinical recognition and treatment of disadvantageous fetal programming development may provide novel approaches for diagnosing and alleviating increased incidence of hypertension in adulthood.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the American Heart Association, Sigma Xi Grants in Aid, National Institutes of Health grants (1K08-HD-060688-1, 1K25-HL-094749-1, and 1R01-DK-088139-01A1), the Center for Women's Health Research, and a University of Colorado Junior Faculty Research Development Award.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.B.D., P.J.R., K.S.H., and V.L.F. conception and design of research; R.B.D., P.J.R., and C.C.P. performed experiments; R.B.D. and K.S.H. analyzed data; R.B.D., P.J.R., K.S.H., and V.L.F. interpreted results of experiments; R.B.D. prepared figures; R.B.D. drafted manuscript; R.B.D., P.J.R., K.S.H., and V.L.F. edited and revised manuscript; R.B.D., P.J.R., K.S.H., and V.L.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laura Brown and Stephanie Thorn of the Perinatal Research Center (PRC) at the University of Colorado at Denver for providing tissue, expertise, and assistance in using the PI-IUGR model. Additionally, we thank the staff at the PRC for assistance and resources for this project. Biochemical assays were run under the advisement of Ivan Stoilov and Robert Mecham, Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO. We thank Kurt Stenmark at the University of Colorado at Denver for helpful conversations about this work. SHG images were taken with the expertise at the Advanced Light Microscopy Core, School of Medicine, University of Colorado at Denver.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abman SH, Shanley PF, Accurso FJ. Failure of postnatal adaptation of the pulmonary circulation after chronic intrauterine pulmonary-hypertension in fetal lambs. J Clin Invest 83: 1849–1858, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJP, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular-disease in adult life. Lancet 341: 938–941, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJP, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ, Wield GA. The relation of small head circumference and thinness at birth to death from cardiovascular-disease in adult life. Br Med J 306: 422–426, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry JS, Anthony RV. The pregnant sheep as a model for human pregnancy. Theriogenology 69: 55–67, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry JS, Rozance PJ, Anthony RV. An animal model of placental insufficiency-induced intrauterine growth restriction. Semin Perinatol 32: 225–230, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendeck M, Keeley FW, Langille B. Perinatal accumulation of arterial-wall constituents: relation to hemodynamic-changes at birth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H2268–H2279, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendeck M, Langille B. Rapid accumulation of elastin and collagen in the aortas of sheep in the immediate perinatal-period. Circ Res 69: 1165–1169, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brar HS, Rutherford SE. Classification of intrauterine growth retardation. Seminars Perinatol 12: 2–10, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkhardt T, Matter C, Lohmann C, Cai H, Luscher T, Zisch A, Beinder E. Decreased umbilical artery compliance and IGF-I plasma levels in infants with intrauterine growth restriction: implications for fetal programming of hypertension. Placenta 30: 136–141, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodson RB, Rozance PJ, Fleenor BS, Petrash CC, Shoemaker LG, Hunter KS, Ferguson VL. Increased arterial stiffness and extracellular matrix reorganization in intrauterine growth-restricted fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 73: 147–154, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodson RB, Rozance PJ, Reina-Romo E, Ferguson VL, Hunter KS. Hyperelastic remodeling in the intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) carotid artery in the near-term fetus. J Biomechanics 46: 956–963, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eberth JF, Popovic N, Gresham VC, Wilson E, Humphrey JD. Time course of carotid artery growth and remodeling in response to altered pulsatility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1875–H1883, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan J. A constitutive model for the mechanical behaviour of soft connective tissues (Abstract). J Biomechanics 20: 681, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ. A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connective Tissue Res 9: 247–248, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faury G. Function,Äìstructure relationship of elastic arteries in evolution: from microfibrils to elastin and elastic fibres. Pathologie Biologie 49: 310–325, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folkow B. Structure and function of the arteries in hypertension. Am Heart J 114: 938–948, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasser T, Ogden R, Holzapfel G. Hyperelastic modelling of arterial layers with distributed collagen fibre orientations (Abstract). J Royal Soc Interface 3: 15, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godfrey KM. Maternal regulation of fetal development and health in adult life. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 78: 141–150, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray PH, O'Callaghan MJ, Harvey JM, Burke CJ, Payton DJ. Placental pathology and neurodevelopment of the infant with intrauterine growth restriction. Dev Med Child Neurol 41: 16–20, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphrey J, Rajagopal K. A constrained mixture model for arterial adaptations to a sustained step change in blood flow. Biomechanics Modeling Mechanobiology 2: 109–126, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphrey JD. Cardiovascular Solid Mechanics: Cells, Tissues, and Organs. New York, NY: Springer, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobs R, Chesler N. The mechanobiology of pulmonary vascular remodeling in the congenital absence of eNOS. Biomechanics Modeling Mechanobiol 5: 217–225, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langille BL. Remodeling of developing and mature arteries - endothelium, smooth-muscle, and matrix. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 21: S11–S17, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langille BL, Brownlee RD, Adamson SL. Perinatal aortic growth in lambs - relation to blood-flow changes at birth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H1247–H1253, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Scott DE, Shandas R, Stenmark KR, Tan W. High pulsatility flow induces adhesion molecule and cytokine mRNA expression in distal pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Ann Biomed Engineering 37: 1082–1092, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li M, Stenmark KR, Shandas R, Tan W. Effects of pathological flow on pulmonary artery endothelial production of vasoactive mediators and growth factors. J Vasc Res 46: 561–571, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson P, Lurbe E, Laurent S. The early life origins of vascular ageing and cardiovascular risk: the EVA syndrome (Abstract). J Hypertens 26: 1049, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phipps K, Barker DJP, Hales CN, Fall CHD, Osmond C, Clark PMS. Fetal growth and impaired glucose-tolerance in men and women. Diabetologia 36: 225–228, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollack RN, Divon MY. Intrauterine growth retardation: definition, classification, and etiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol 35: 99–107, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezakhaniha R, Agianniotis A, Schrauwen JT, Griffa A, Sage D, Bouten CV, van de Vosse FN, Unser M, Stergiopulos N. Experimental investigation of collagen waviness and orientation in the arterial adventitia using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Biomechanics Modeling Mechanobiol 11: 461–473, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rondo PHC, Lemos JO, Pereira JA, Oliveira JM, Innocente LR. Relationship between birthweight and arterial elasticity in childhood. Clin Sci 115: 317–326, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozance PJ, Crispo MM, Barry JS, O'Meara MC, Frost MS, Hansen KC, Hay WW, Brown LD. Prolonged maternal amino acid infusion in late-gestation pregnant sheep increases fetal amino acid oxidation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E638–E646, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozance PJ, Limesand SW, Barry JS, Brown LD, Hay WW. Glucose replacement to euglycemia causes hypoxia, acidosis, and decreased insulin secretion in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr Res 65: 72–78, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rozance PJ, Seedorf GJ, Brown A, Roe G, O'Meara MC, Gien J, Tang JR, Abman SH. Intrauterine growth restriction decreases pulmonary alveolar and vessel growth and causes pulmonary artery endothelial cell dysfunction in vitro in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L860–L871, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozario T, Desimone DW. The extracellular matrix in development and morphogenesis: a dynamic view. Dev Biol 341: 126–140, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safar M. Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 107: 2864–2869, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shadwick R. Mechanical design in arteries. J Exp Biol 202: 3305–3313, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sims TJ, Bailey AJ. Quantitative analysis of collagen and elastin cross-links using a single-column system. J Chromatogr 582: 49–55, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Starcher B, Conrad M. A role for neutrophil elastase in the progression of solar elastosis. Connective Tissue Res 31: 133–140, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson JA, Gros R, Richardson BS, Piorkowska K, Regnault TR. Central stiffening in adulthood linked to aberrant aortic remodeling under suboptimal intrauterine conditions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R1731–R1737, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson JA, Richardson BS, Gagnon R, Regnault TR. Chronic intrauterine hypoxia interferes with aortic development in the late gestation ovine fetus. J Physiol 589: 3319–3332, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagenseil JE, Mecham R. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev 89: 957–989, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells SM, Langille B, Lee JM, Adamson S. Determinants of mechanical properties in the developing ovine thoracic aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1385–H1391, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]