Abstract

Microvascular insufficiency contributes to cardiac hypertrophy and worsens heart dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Our recent study shows that apelin may protect ischemic heart failure via upregulation of sirtuin 3 (Sirt3) and angiogenesis. This study investigated whether apelin promotes angiogenesis and ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy via activation of Sirt3. Wild-type (WT) and diabetic db/db mice were administrated with adenovirus-apelin to overexpressing apelin. In WT mice, overexpression of apelin increased Sirt3, VEGF/VEGFR2, and angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1)/Tie-2 expression in the heart. In vitro, treatment of endothelial cells (EC) with apelin increased VEGF and Ang-1 expression. In EC isolated from Sirt3KO mice, however, apelin treatment did not upregulate VEGF and Ang-1 expression. Moreover, apelin-induced angiogenesis was diminished in Sirt3KO mice. In db/db mice, the basal levels of apelin and Sirt3 expression were significantly reduced in the heart. This was accompanied by a significant reduction of capillary and arteriole densities in the heart. Overexpression of apelin increased Sirt3, VEGF/VEGFR2, and Ang-1/Tie-2 expression together with improved vascular density in db/db mice. Overexpression of apelin further improved cardiac function in db/db mice. Treatment with apelin significantly attenuated high glucose (HG)-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and EC apoptosis. The protection of apelin against HG-induced ROS formation and EC apoptosis was diminished in Sirt3KO-EC. We conclude that apelin gene therapy increases vascular density and alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy by a mechanism involving activation of Sirt3 and upregulation of VEGF/VEGFR2 and Ang-1/Tie-2 expression.

Keywords: apelin, sirtuin 3, Ang-1/Tie-2, VEGF/VEGFR2, angiogenesis, diabetic cardiomyopathy

diabetes is becoming an epidemic worldwide due to increased sedentary lifestyles, overnutrition, and an escalating aging population. Heart disease is increased by up to 10-fold in people with diabetes compared with the general age-matched population. Diabetic cardiomyopathy is a leading cause of heart failure in diabetic patients. Heart failure contributes to higher morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes (3, 39, 47). Impairment of angiogenesis is a major microvascular complication of diabetic patients. Impaired angiogenic growth factor expression and angiogenesis contribute and exacerbate the clinical manifestations of diabetes such as delayed wound healing, critical limb ischemia, and myocardial ischemia (1, 13, 19). Previously, we have shown that VEGF, angiopoietins, and Tie-2 expression are impaired in the hearts of diabetic db/db mice (8, 9). Reduction of VEGF expression and vascular density in diabetic heart also contributes to cardiac dysfunction and progressive heart failure (33, 48). In contrast, the preservation of VEGF expression is associated with the maintenance of a normal capillary density and left ventricular function in diabetes (33). These studies implicate a critical role of myocardial angiogenesis in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and highlight that angiogenic growth factor gene therapy could improve myocardial angiogenesis and diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Apelin, a bioactive peptide isolated from bovine gastric extract, is an endogenous ligand of the human G-protein-coupled receptor APJ (28, 45). Apelin/APJ is expressed in multiple tissues, including vascular endothelial cells and myocardium (16, 26). Apelin has requisite roles for vascular development and has been detected in the region around presumptive blood vessels during early embryogenesis and overlapped with the expression of APJ in the cardiovascular system (15, 24, 52). Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) are the two ligands of the Tie-2 that is expressed on the endothelium. The angiopoietin/Tie-2 system has a critical role in the regulation of vascular maturation and angiogenesis (21, 22). Previous study shows that knockdown of apelin attenuates Tie-2 expression and disrupts blood vessel formation, indicating that angiopoietins/Tie-2 system may act as downstream of apelin signaling and mediate apelin-induced angiogenesis (15, 24, 52). So far, the molecular mechanism by which apelin regulates angiopoietins/Tie-2 expression remains unknown. Sirtuins regulate posttranslational modification of histone protein by coupling lysine deacetylation to NAD+ hydrolysis (35, 44). Sirtuin 3 (Sirt3) is a longevity factor that is closely associated with the prolong lifespan (2, 27, 36). Our recent study shows that intramyocardial injection with apelin overexpressed-bone marrow cells leads to a significant increase in Sirt3 expression in the ischemic heart. This is accompanied by significant increases in Ang-1 and Tie-2 expression in post-myocardial infarction (MI) mice (30). Apelin/APJ has been reported to be downregulated in severe and decompensated heart failure (43). The expression of apelin and APJ is also decreased in diabetic db/db mice (53, 54). Our study has shown that upregulation of apelin expression is associated with improvement of angiogenesis and cardiac function in post-MI db/db mice (50). In this study, we hypothesized that apelin gene therapy improves myocardial vascular density and cardiac function via modulation of Sirt3 in diabetic db/db mice.

To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether: 1) Sirt3 is necessary for apelin-induced angiogenic growth factor expression and angiogenesis, and 2) apelin gene therapy increases vascular density and attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy. We demonstrated that apelin-induced angiogenesis is dependent on Sirt3. Furthermore, apelin gene therapy enhanced vascular density and improved cardiac function via upregulation of Sirt3, VEGF/VEGFR2, and Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling pathways in diabetic cardiomyopathy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures conformed to the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol ID: 1280). The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Animal studies.

The B6.BKS-Leprdb/J (db/db) male mice, control db+/− male mice, and C57BL/6J male (wild type) at age of 8 wk were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Global Sirt3 knockout mice and wild-type control of Sirt3 mice (WT) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and breeding by our laboratory. Male Sirt3KO and WT mice at age 18 wk were used for the experiments.

C57BL/6J WT mice, db+/−, and diabetic db/db male mice at 12 wk of age were divided into following: 1) Ad-GFP + C57BL/6J mice; 2) Ad-apelin (Ad-AP) + C57BL/6J mice; 3) Ad-β-gal + db+/− mice; 4)Ad-β-gal + db/db mice; and 5) Ad-apelin (Ad-AP) + db/db mice. Experimental mice received an intravenous tail vein injection of Ad-apelin [1 × 109 plaque-forming units (PFU)], Ad-GFP (1 × 109 PFU), or Ad-β-gal (1 × 109 PFU) (46). After 6 wk of Ad-apelin, Ad-GFP, or Ad-β-gal administration, experimental mice were killed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia with isoflurane.

Blood was obtained from experimental mice by tail snip, and blood glucose levels were measured with the use of One Touch SureStep test strips and a meter. Glucose levels were expressed as milligram per deciliter.

Western analysis of Sirt3, Sirt1, Tie-2, VEGF, VEGFR2, apelin, Ang-1, and Ang-2 expression.

The hearts were harvested and homogenized in 300 μl of lysis buffer, and total protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Fifteen micrograms of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The blot was probed with Sirt3, Sirt1, Tie-2, and VEGFR2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling); VEGF, apelin, and Ang-2, (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); and Ang-1 (1:1,000; Sigma) antibodies. The membranes were then washed and incubated with a secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase, and densitometric analysis was carried out using image acquisition and analysis software (TINA 2.0).

Analysis of myocardial capillary and arteriole densities.

Eight-micrometer sections were cut and incubated with fluorescerin-labeled Griffonia Bandeiraea Simplicifolia Isolectin B4 (1: 100; IB4; Invitrogen) and Cy3-conjugated anti-α smooth muscle actin (SMA; 1: 200; Sigma). The number of capillaries (IB4-positive EC) was counted and expressed as capillary density per square millimeter of tissue. Myocardial arteriole (SMA-positive smooth muscle cells located in vascular walls) density was measured using image analysis software (ImageJ; National Institutes of Health) (6).

Myocardial cell apoptosis.

Heart tissue sections underwent transferase deoxyuridine nick end labeling (TUNEL) following the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Sections were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Apoptosis was indexed by counting TUNEL-positive cells (green) per 100 nuclei per section (46).

Hemodynamic measurements.

After 6 wk of Ad-apelin or Ad-β-gal gene therapy, experimental mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) plus xylazine (15 mg/kg), intubated, and artificially ventilated with room air. A 1.4-Fr pressure-conductance catheter (SPR-839; Millar Instrument) was inserted into the left ventricle (LV) to record baseline cardiac hemodynamics of the hearts. Raw conductance volumes were corrected for parallel conductance by the hypertonic saline dilution method (50).

Echocardiography.

Transthoracic two-dimensional M-mode echocardiography was performed using a Visual Sonics Vevo 770 Imaging System (Toronto, Canada) equipped with a 707B high-frequency linear transducer. Mice were anesthetized using a mixture of isoflurane (1.5%) and oxygen (0.5 l/min). The short-axis imaging was taken as M-mode acquisition for 30 s. Data analysis was performed with the use of a customized version of Vevo 770 Analytic Software (Toronto, Canada).

Heart weight-to-body weight ratio and cardiac hypertrophy.

Cardiac hypertrophy was assessed by measuring heart-to-body weight ratio. Each heart weight was divided by the total body weight of the mouse, resulting in a ratio representative of cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiac hypertrophic gene β-myosin heavy chain expression was examined by Western blot analysis (6).

Mouse aortic sprouting assay in ex vivo model.

Mouse aortas isolated from WT, Sirt3KO, and db/db mice were placed in the culture dishes and overlaid with 300 μl of ECM gel and 20% FBS endothelial growth medium (EGM). Vessel outgrowth at days 5–8 was examined using EVOS microscope (AMG). Vessel sprouting was quantified by measuring the relative area of aorta explants outgrowth using image acquisition and analysis software (Image J, NIH) (8).

Cultured bone marrow-derived ECs.

Sirt3 knockout and control WT mice were killed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia with isoflurane. BM-derived endothelial cells were obtained by flushing the tibias and femurs with 10% FBS EGM. Immediately after isolation, 105 BM-derived cells were plated into 6-well culture plates. After 4 days of culture, the nonadherent cells were removed and the adherent cells were cultured by 10% EGM (29, 46). When confluent, bone marrow-derived ECs (BMECs) were analyzed by immunocytochemistry to assess the expression of endothelium-specific markers (vWF, CD31 or eNOS, and isolectin IB4). The identified BMEC was then cultured. The primary cultured BMECs, passages between 4 and 5, were used for the experiments.

BMEC tube formation.

Capillary-like tubule formation was performed as previous described (5).

BMEC proliferation and apoptosis.

For the cell proliferation measurement, BMECs were cultured in 10% FBS EGM for 72 h. The proliferative capacity of cultured BMECs was assayed using a cell proliferation (MTT) kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostic, IN) (7, 9). In the apoptosis study, BMEC apoptosis was induced by exposure of cultured BMECs to serum-free medium for 48 h or high glucose (HG; 25 mM). The number of apoptotic cells was then examined by counting TUNEL positive cells per 100 nuclei in cultured BMECs.

Measurement of intracellular ROS formation in cultured BMECs.

Intracellular ROS were determined by oxidative conversion of cell permeable chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes) to fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Briefly, BMECs cultured in two-well chamber slides were incubated with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA in PBS for 30 min. DCF fluorescence was measured over the whole field of vision using an EVOS fluorescence microscope connected to an imaging system as previously described (10, 12).

Statistical analysis.

The results were expressed as the means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons test (Student-Newman-Keuls) or student t-test. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Knockout of Sirt3 reduces angiogenic growth factor expression and angiogenesis.

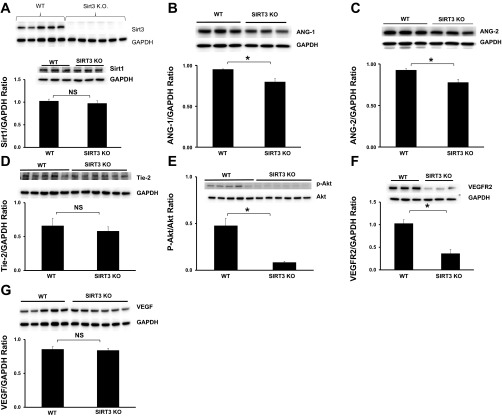

First, we examined whether knockout of Sirt3 alters other proangiogenic isoforms of sirtuins expression in the heart. As shown in Fig. 1A, Sirt3 expression was absent in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice. Knockout of Sirt3 had little effect on Sirt1 expression in the heart (Fig. 1A). To investigate whether Sirt3 is associated with myocardial angiogenesis, the expression of angiopoietins/Tie-2 and VEGF/VEGFR2 was examined in Sirt3KO mice. Western blot analysis revealed that the basal levels of Ang-1 and Ang-2 were significantly reduced in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice when compared with WT mice (Fig. 1, B and C). The basal levels of Tie-2 were also decreased but did not reach significantly difference when compared with the hearts of WT mice (Fig. 1D). Intriguingly, Akt phosphorylation, the downstream mediator of Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling, was abolished in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice (Fig. 1E). Moreover, VEGFR2 expression was significantly reduced while VEGF expression was not significantly different in Sirt3KO mice as compared with WT mice (Fig. 1, F and G).

Fig. 1.

Knockout of sirtuin 3 (Sirt3) reduces angiogenic growth factor expression. A: representative Western blot analysis of Sirt1 and Sirt3 expression. Sirt3 expression was absent in hearts of Sirt3KO mice (n = 5 mice; top). Sirt1 expression was not significantly difference in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice compared with wild-type (WT) mice (bottom; n = 3 mice; P > 0.05). NS, no statistic difference. B: representative images and Western blot analysis of angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) expression. Ang-1 expression was significantly reduced in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice compared with WT control mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). C: Western blot analysis demonstrating that Ang-2 expression was significantly reduced in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice compared with WT control mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). D: representative Western blot analysis of Tie-2 in the hearts of WT and Sirt3KO mice. There was no significantly difference in Tie-2 expression between WT and Sirt3KO mice (n = 5–6 mice; P > 0.05). E: Western blot analysis demonstrating that the phosphorylation levels of Akt were significantly reduced in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice compared with WT control mice (n = 5–6 mice; *P < 0.05). F: Western blot analysis demonstrating that VEGFR2 expression was significantly decreased in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice compared with WT control mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). G: Western blot analysis demonstrating that VEGF expression was no significantly difference between WT and Sirt3KO mice (n = 5–6 mice; P > 0.05).

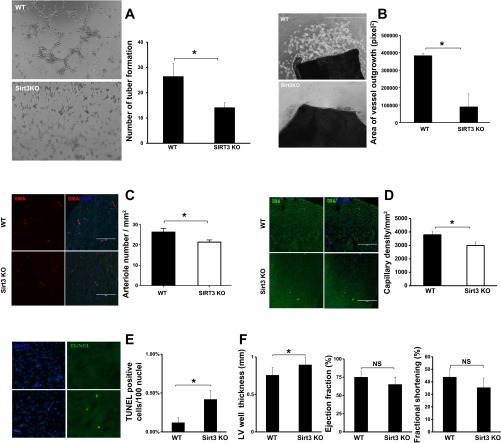

Next, the angiogenic activity was examined in EC isolated from WT and Sirt3KO mice. As shown in Fig. 2A, basal levels of EC tube formation were significantly reduced in Sirt3KO mice compared with those of WT mice. Using aortic sprouting explants of angiogenesis model ex vivo, we further examined basal levels of vessel sprouting in Sirt3KO mice. Ex vivo angiogenesis analysis showed that basal levels of vessel sprouting were significantly reduced in Sirt3KO mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2B). Knockout of Sirt3 further significantly reduced arteriole density compared with WT control hearts (Fig. 2C). Myocardial capillary density was also significantly reduced in Sirt3KO mice when compared with WT control mice (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Knockout of Sirt3 reduces angiogenesis and increases myocardial apoptosis. A: representative images and quantitative analysis of endothelial cell (EC) tube formation. There was few tubule structures in EC isolated from Sirt3KO mice compared with EC from WT mice. Quantitative analysis of tube number showed that the number of tube formation was significantly reduced in Sirt3KO-EC (n = 3; *P < 0.05). B: representative images and quantitative analysis of vessel sprouting in WT mouse and Sirt3KO mouse vessel explants. Quantitative analysis revealed that the area of vessel sprouting was significant reduced in Sirt3KO mice (n = 4 mice) compared with WT mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). C: representative images and quantitative analysis of arteriole density in WT mice and Sirt3KO mice. Arteriole was stained by smooth muscle actin (SMA, red) and nuclei were stained by DAPI (blue, ×40). Merged images show that the arteriole density was decreased in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice compared with control WT mice (n = 3–4 mice; *P < 0.05). D: representative images and quantitative analysis of capillary density in hearts of WT mice and Sirt3KO mice. Capillary was stained with the EC marker IB4 (green) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Myocardial capillary density was reduced in Sirt3KO mice compared with control WT mice (n = 3–4 mice; *P < 0.05). E: representative images and quantitative analysis of transferase deoxyuridine nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells showing apoptotic cells were significantly increased in the heart of Sirt3KO mice (n = 4) compared with that of control WT mice (n = 3; *P < 0.05). Apoptotic cells were stained by TUNEL (green)-positive and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). F: echocardiography was performed on WT mice and Sirt3KO mice. Left vetricular (LV) wall thickness was significantly increased in Sirt3KO mice (n = 6) compared with WT mice (n = 7; *P < 0.05). Ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) were declined in Sirt3KO mice, but there was no statistically significant difference when compared with WT mice (P > 0.05).

Intriguingly, the number of apoptotic cells was higher in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice than WT mice (Fig. 2E). Echocardiography analysis further showed that the LV wall thickness of Sirt3KO mice was significantly higher than that of WT mice (Fig. 2F). The ejection fraction (EF%) and fractional shortening (FS%) were decreased in Sirt3KO mice but did not reach a significant difference compared with WT mice (P = 0.073 and 0.065; Fig. 2F).

Sirt3 is essential for apelin-mediated angiogenesis and antiapoptosis.

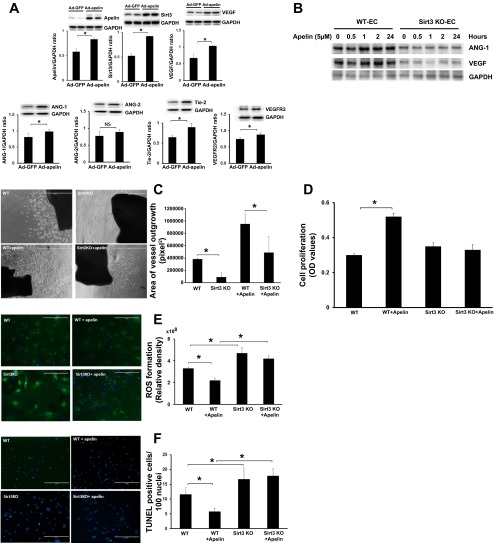

Systemic administration of Ad-apelin (Ad-AP) led to a dramatic increase in Sirt3 expression in the hearts of WT mice. This was accompanied by a dramatic upregulation of Ang-1, Tie-2, VEGF, and VEGFR2 expression. Ang-2 expression, however, was not changed in the hearts of Ad-apelin-treated mice (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Apelin-mediated angiogenesis and suppression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and apoptosis is dependent on Sirt3. A: representative Western blot analysis of apelin, Sirt3, Ang-1, Ang-2, Tie-2, VEGF, and VEGFR2 in the hearts of WT treated with Ad-apelin. Myocardial apelin was overexpressed in Ad-apelin-treated mice. Sirt3, Ang-1, Tie-2, VEGF, and VEGFR2 expression was upregulated in Ad-apelin-treated mice compared with Ad-GFP-treated mice (n = 3–6 mice; *P < 0.05). B: representative images of Western blot analysis of apelin treatment on Ang-1 and VEGF expression in EC isolated from WT and Sirt3KO mice. C: representative images and quantitative analysis of vessel outgrowth area in WT mouse, Sirt3KO mouse, WT + apelin, and Sirt3KO + apelin vessel explants. Quantitative analysis revealed that treatment of aorta rings isolated from WT mice with apelin led to a significant increase in vessel outgrowth (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). The area of vessel sprouting was significantly less in Sirt3KO + apelin-treated mice than WT + apelin-treated mice (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). D: measurement of proliferation rate by MTT assay. Treatment of EC with apelin significantly increased cell proliferation. Apelin-induced proliferative rate of EC was significantly reduced in cultured EC of Sirt3KO mice compared with that of WT mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). OD, optical density. E: representative images and quantification of intracellular ROS formation in cultured ECs isolated from WT and Sirt3KO mice. ROS formation was stained with CM-H2DCFDA (green). ROS formation was significantly increased in cultured ECs of Sirt3KO mice compared with that of WT mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). Treatment with apelin resulted in a significant reduction of ROS formation whereas knockout of Sirt3 diminished apelin-mediated suppression of ROS formation (n = 3; *P < 0.05). F: representative images and quantification of cell apoptosis in cultured ECs isolated from WT and Sirt3 KO mice. Apoptotic cells were stained by TUNEL+ cells (green) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). EC apoptosis was significantly increased in cultured ECs of Sirt3KO mice compared with that of WT mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). Treatment with apelin resulted in a significant reduction of ECs apoptosis whereas knockout of Sirt3 blunted anti-apoptotic effects of apelin in cultured ECs (n = 3; *P < 0.05).

Using EC isolated from WT and Sirt3KO mice, we next investigated whether Sirt3 contributes to apelin-mediated angiogenesis. Treatment with apelin (5 μM) led to a gradual increase in Ang-1 and VEGF expression seen at 1 h and up to 24 h in WT-EC, whereas apelin treatment did not increase Ang-1 and VEGF expression in Sirt3KO-EC (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, treatment of WT mouse aorta explants with apelin (5 μM) led to more robust vessel sprouting compared with control without apelin. Apelin treatment also increased vessel sprouting in Sirt3KO mice but was significantly less than WT mice (Fig. 3C).

In addition, treatment of EC with apelin (5 μM) resulted in a significant increase in cell proliferation. However, treatment of Sirt3KO-EC with apelin did not to promote cell proliferation (Fig. 3D). Loss of Sirt3 also significantly enhanced ROS formation and cell apoptosis in EC. Treatment of EC with apelin (5 μM) resulted in a significant reduction of ROS formation and cell apoptosis. Moreover, loss of Sirt3 in EC significantly blunted apelin-induced suppression of ROS formation and cell apoptosis (Fig. 3, E and F).

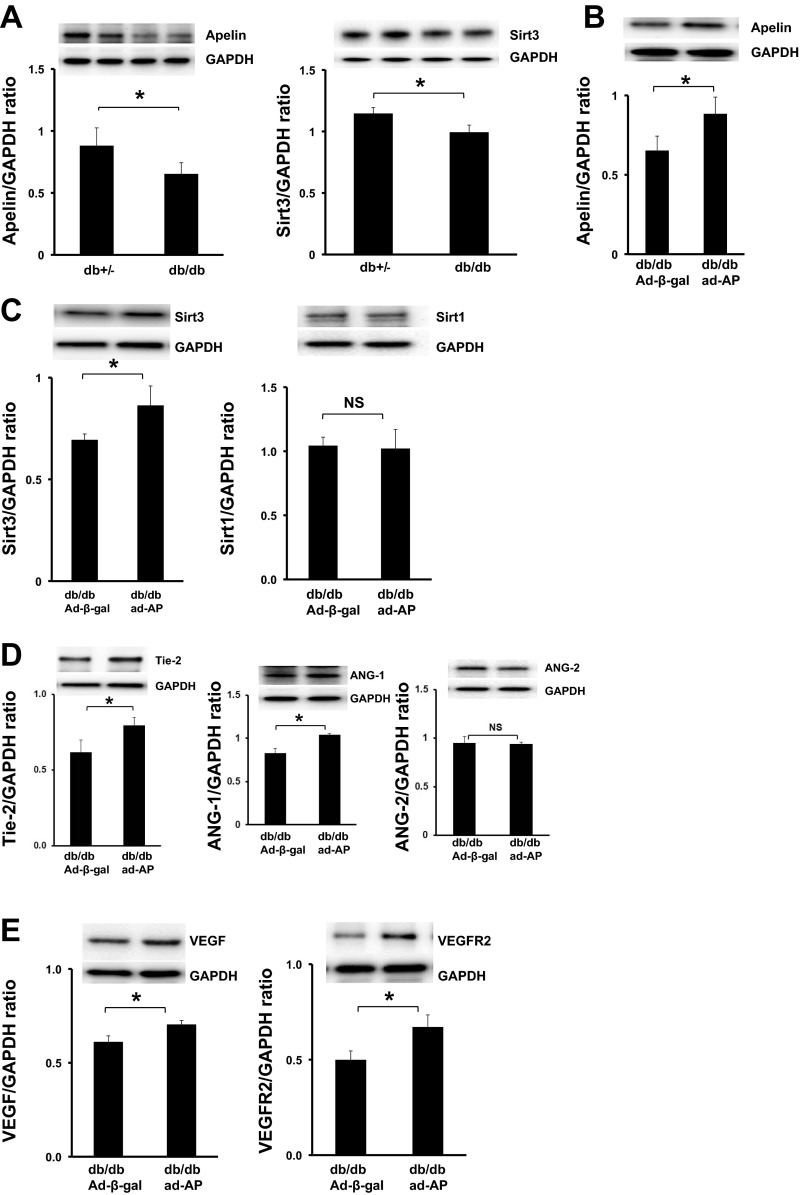

The expression of apelin and Sirt3 is decreased in the hearts of db/db mice.

As shown in Fig. 4A, the basal level of apelin expression was significantly decreased in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. To determine whether Sirt3 is involved in diabetes-associated reduction of myocardial vascular density, the levels of Sirt3 were examined in the hearts of db/db mice. Sirt3 expression was significantly reduced in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Apelin gene therapy upregulates Sirt3 and angiogenic growth factor expression in db/db mice. A: Western blot analysis showing apelin and Sirt3 expression was significantly decreased in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice (n = 5–6 mice; *P < 0.05). B: Western blot analysis showing systemic administration of Ad-apelin [1 × 109 plaque-forming units (PFU) Ad-apelin] resulted in overexpression of apelin in the hearts of db/db mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). C: Western blot analysis showing overexpression of apelin led to a significant upregulation of Sirt3 expression in db/db mice compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). Sirt-1 expression was not significantly difference in the hearts of Ad-apelin + db/db mice compared with Ad-β-gal + db/db mice (n = 3 mice, P > 0.05). D: Western blot analysis showing overexpression of apelin resulted in a significant increase in Tie-2 expression compared with Ad-β-gal-treated db/db mice (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). Overexpression of apelin led to a significant upregulation of Ang-1 expression but not Ang-2, in db/db mice compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). E: Western blot analysis showing overexpression of apelin resulted in significant increases in VEGF and VEGFR2 expression in db/db mice compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05).

Apelin gene therapy increases Sirt3, VEGF/VEGFR2, and Ang-1/Tie-2 expression in diabetic heart.

We then examined whether systemic administration of Ad-apelin increases apelin and Sirt3 expression in the hearts of diabetic db/db mice. As shown in Fig. 4B, apelin expression was significantly increased in db/db mice after systemic delivery of Ad-apelin. Overexpression of apelin further led to a significant increase in Sirt3 expression, but had little effect on Sirt1 expression, in the hearts of db/db mice compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (Fig. 4C).

Next, we examined whether overexpression of apelin regulates angiopoietins/Tie-2 and VEGF/VEGFR2 expression. Overexpression of apelin significantly upregulated Tie-2 and Ang-1 expression but did not affect Ang-2 expression in db/db mouse hearts (Fig. 4D). Overexpression of apelin also resulted in significant increases in VEGF and VEGFR2 expression in the hearts of db/db mice when compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (Fig. 4E).

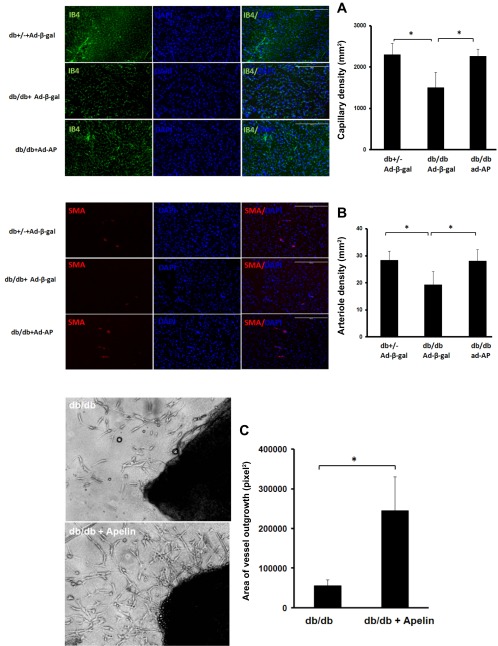

Overexpression of apelin increases vascular density in the hearts of db/db mice.

We further examined whether overexpression of apelin increases myocardial vascular density. Myocardial capillary and arteriole densities were significantly reduced in db/db mice when compared with control db+/− mice. Overexpression of apelin significantly increased myocardial capillary and arteriole densities in db/db mice compared with db/db mice that received the Ad-β-gal treatment (Fig. 5, A and B). Similarly, treatment of db/db mouse aortic explants with apelin (5 μM) dramatically increased vessel sprouting in db/db mouse aortic explants (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Apelin increases myocardial vascular density in db/db mice A: capillary was stained with EC marker IB4 (green) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Capillary density was reduced in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. Capillary density was significantly increased in the hearts of db/db treated with Ad-apelin as compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). B: arteriole was stained with SMA (red) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The arteriole density was decreased in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. Apelin gene therapy resulted in a dramatic increase in arteriole density as compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). C: representative images of vessel sprouting and quantitative analysis of vessel outgrowth area in db/db and db/db + apelin-treated vessel explants. Quantitative analysis area of vessel outgrowth revealed that treatment of aortic explants isolated from db/db mice with apelin (5 μM) for 5–8 days led to a significant increase in vessel outgrowth (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05).

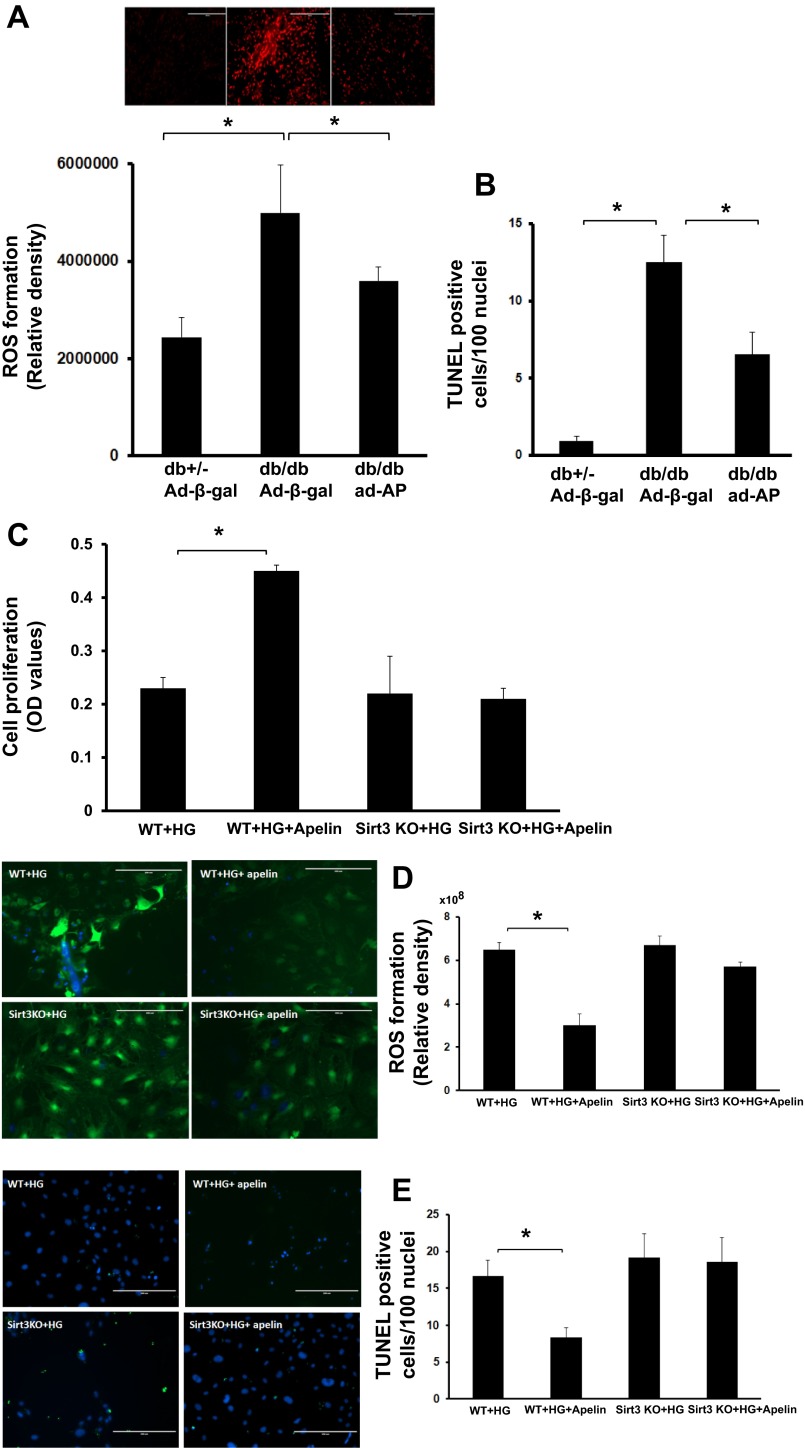

Overexpression of apelin attenuates myocardial ROS formation and apoptosis in db/db mice.

DHE staining revealed that ROS formation was significantly enhanced in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. Overexpression of apelin resulted in a significant reduction of ROS formation in db/db mice compared with db/db mice that received the Ad-β-gal (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Apelin attenuates diabetes and high glucose-induced ROS formation and EC apoptosis. A: ROS were stained by DHE (red) in the hearts. DHE staining and quantitative analysis showing that ROS formation was significantly increased in the hearts of db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. Overexpression of apelin significantly suppressed ROS formation compared with that of db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 5 mice; *P < 0.05). B: quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells showing TUNEL+ cells were significantly increased in the Ad-β-gal-treated db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. Significantly fewer TUNEL+ cells were seen in the Ad-apelin-treated db/db mice (n = 6 mice; *P < 0.05). C: treatment with apelin significantly increased EC proliferation under high-glucose conditions. Apelin-induced EC proliferation was significantly blunted in cultured EC of Sirt3KO mice under high glucose conditions (n = 3 mice; *P < 0.05). D: ROS was stained with CM-H2DCFDA (green). Treatment of EC with apelin significantly reduced high glucose-induced ROS formation whereas knockout of Sirt3 in EC abolished apelin-mediated inhibition of high glucose-induced ROS formation (n = 3; *P < 0.05). E: apoptotic cells were stained by TUNEL (green) and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Treatment of EC with apelin led to a significant suppression of high glucose-induced apoptosis. Treatment with apelin did not suppress high glucose-induced cell apoptosis in EC isolated from Sirt3KO mice (n = 3; *P < 0.05).

The number of TUNEL-positive cells was significantly higher in the hearts of db/db mice than the control db+/− mice. Overexpression of apelin significantly reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells in db/db mice compared with db/db mice that received the Ad-β-gal (Fig. 6B).

Apelin attenuates HG-induced ROS formation and apoptosis via Sirt3.

To further explore whether apelin treatment attenuates diabetes-induced EC dysfunction via activation of Sirt3, parallel studies were performed in WT-EC and Sirt3KO-EC that were exposed to apelin under HG (25 mM) conditions. Under HG conditions, treatment of EC with apelin led to a significant increase in cell proliferation, whereas treatment of Sirt3KO-EC with apelin had little effect on cell proliferation (Fig. 6C). Apelin treatment also significantly attenuated HG-induced ROS formation and cell apoptosis. Knockout of Sirt3 in EC significantly blunted apelin-induced suppression of ROS formation and cell apoptosis under HG conditions (Fig. 6, D and E).

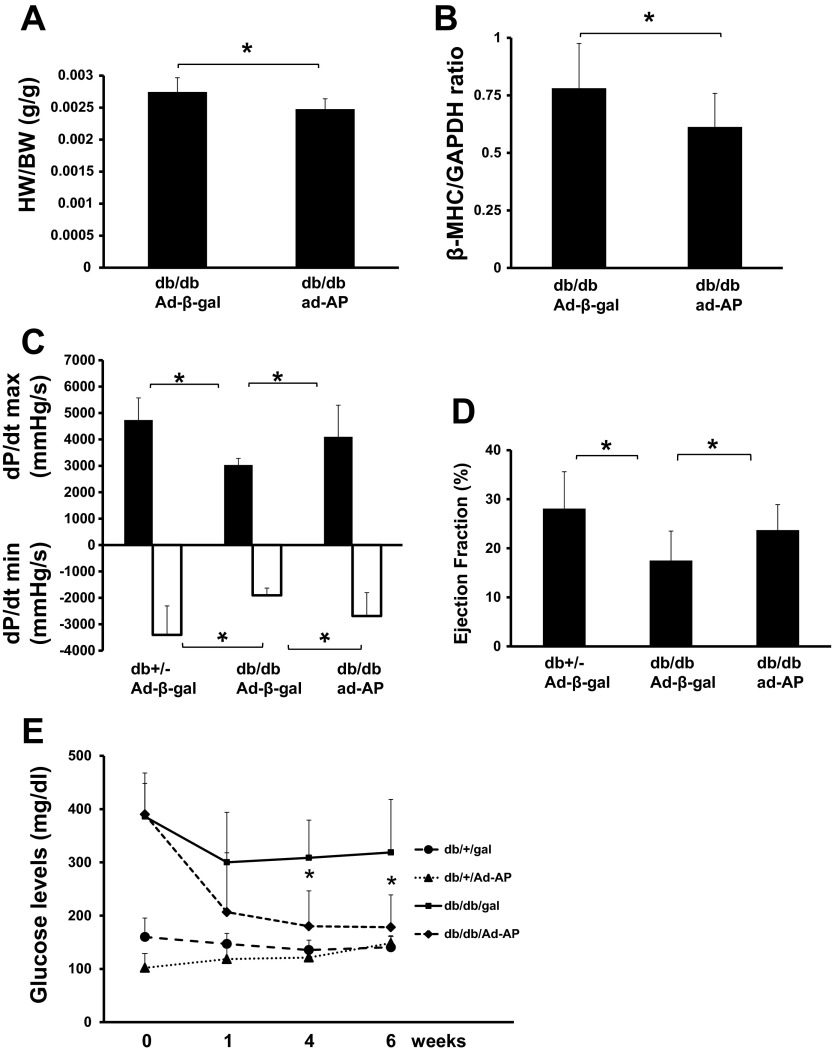

Overexpression of apelin attenuates diabetic cardiac hypertrophy and improves cardiac function.

Overexpression of apelin led to a significant reduction of heart/body weight ratio and β-myosin heavy chain protein expression when compared with db/db mice that received the Ad-β-gal (Fig. 7, A and B). Diabetic db/db mice showed a significant reduction of cardiac function, reflected by decreased ejection fraction (EF%) and +dP/dtmax pressure together with elevated −dP/dtmin pressure when compared with control db+/− mice. Overexpression of apelin in db/db mice resulted in a significant improvement of these variables compared with db/db mice received Ad-β-gal treatment (Fig. 7, C and D). In addition, glucose levels were significantly decreased in Ad-apelin-treated db/db mice compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal. Ad-apelin treatment had little effect on the glucose levels in the control db+/− mice (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Apelin gene therapy attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and improves cardiac function in db/db mice. A: ratio of heart and body weight (HW/BW) showing that overexpression of apelin significantly reduced HW/BW ratio compared with Ad-β-gal-treated db/db mice (n = 10 mice; *P < 0.05). B: Western blot analysis showing overexpression of apelin significantly reduced cardiac β-myosin heavy chain (MHC) expression compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 10 mice; *P < 0.05). C: representative cardiac function of pressure-volume (P-V) loop analysis. P-V loop analysis showing that maximum +dP/dt pressure was decreased whereas minimum −dP/dt pressure was elevated in db/db mice compared with control db+/− mice. Apelin gene therapy significantly improved maximum +dP/dt and minimum −dP/dt pressures as compared with that of db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal. n = 8 mice,*P < 0.05. D: P-V loop analysis showing that cardiac ejection fraction (EF%) was reduced in db/db mice as compared with control db+/− mice. Apelin gene therapy significantly increased EF% as compared with db/db mice treated with Ad-β-gal (n = 8 mice; *P < 0.05). E: effects of apelin on blood glucose levels in db/db mice. Systemic delivery of Ad-apelin in db/db mice led to a significant decrease in fasting blood glucose levels compared with Ad-β-gal-treated db/db mice during 6 wk of the studies (n = 10; *P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our data, for the first time, demonstrated that knockout of Sirt3 attenuates apelin-induced angiogenesis and suppression of ROS formation. We also found that apelin gene therapy alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy by increasing myocardial vascular density via a mechanism involving upregulation of Sirt3 signaling pathway and increases in Ang-1/Tie-2 and VEGF/VEGFR2 expression.

Sirt3 is metabolic sensor that couples energy and oxygen homeostasis (18). Sirt3 has been reported to be a major mitochondrial deacetylase in human (2, 36). Previous studies reveal that Sirt3 is detected only in the mitochondria of the hearts (37, 41). Sirt3 protein levels are significantly reduced with aging, and exercise increases Sirt3 levels both in young and old individuals (27). Sirt3 activity is regulated by nutritional stress. Nutrient deprivation has been shown to increase levels of Sirt3 in mice (34). Our present study showed that knockout of Sirt3 significantly increased EC apoptosis. Moreover, knockout of Sirt3 completely blunted the protection of apelin against EC apoptosis, implicating that activation of Sirt3 is important for the cell survival under oxidative stress. Most recent studies demonstrate that Sirt3 expression is reduced during nutrient excess and by feeding mice with a high-fat diet (14, 18, 20). Sirt3 expression is also significantly decreased in patients with diabetes (4). Our present study, for the first time, demonstrated that basal levels of Sirt3 were significantly reduced in the hearts of db/db mice. Our data further showed that knockout of Sirt3 exhibited a very similar cardiac phenotypic pattern as diabetic db/db cardiomyopathy with reduction of angiogenic growth factor and VEGFR2 expression and myocardial vascular density. Knockout of Sirt3 in EC further abolished apelin-mediated improvement of EC function under hyperglycemic conditions. Upregulation of Sirt3 by apelin gene therapy reduced myocardial apoptosis and hypertrophy and significantly improved myocardial vascular density and cardiac function in db/db mice. These data implicate a critical role of Sirt3 in diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Apelin has been shown previously to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via suppression of ROS formation (51). Moreover, apelin attenuates pressure-overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy through a ROS-dependent mechanism in mice (17). However, the underlying mechanisms by which apelin attenuates ROS formation and cardiac hypertrophy are not completely understood. Knockdown of Sirt3 in cells has been reported to increase ROS formation (25). Moreover, cardiomyocytes isolated from Sirt3KO mice show increased ROS production (40). Consistent with these findings, our present data showed that knockout of Sirt3 in EC led to a significant increase in ROS formation. This was accompanied by a significant increase in cardiac hypertrophy in Sirt3 KO mice. Our data also showed that apelin-induced suppression of ROS formation was significantly blunted in EC isolated from Sirt3KO mice, implicating that inhibitory effect of apelin on ROS formation is mediated, at least in part, by activation of endothelial Sirt3. Surprisingly, knockout of Sirt3 in EC did not further increased ROS formation and apoptosis under HG conditions. This discrepancy maybe due to exposure of EC to HG impaired Sirt3 function, thus leading to mitochondria dysfunction, increased ROS formation, and apoptosis in WT-ECs. Therefore, loss of Sirt3 did not further enhance HG-induced ROS formation and apoptosis. Nevertheless, our study provides evidence that apelin ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy through a Sirt3-dependent suppression of ROS formation.

In present study, we also revealed that treatment with apelin increased EC proliferation whereas knockout of Sirt3 abolished apelin-induced EC proliferation. Furthermore, treatment of apelin significantly increased endothelial cell sprouting and promoted angiogenesis in WT and diabetic db/db mice. Most importantly, apelin gene therapy significantly reduced cardiac hypertrophy and improved heart function in db/db mice. It is well documented that cardiomyocytes size and cardiac function are dependent on angiogenesis. Cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis are coordinately regulated during physiological or adaptive cardiac growth. Disruption of the balanced growth and angiogenesis leads to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (23, 38). Endothelial proliferation is a major determinant in the angiogenesis process while apoptosis is a key contributor to vessel regression or reduction of vascular density during disease progression such as diabetic cardiomyopathy (11). Our present study showed that apoptosis was significantly increased in EC of Sirt3KO mice. The number of apoptotic cells was also increased in the heart of Sirt3KO mice together with reduction of vascular density. Moreover, Akt phosphorylation was abolished in the heart of Sirt3KO mice. This was accompanied by a significant increase in cardiac hypertrophy. Our data implicate that increased endothelial cell apoptosis may contribute to reduction of vascular density and cardiac hypertrophy in Sirt3KO mice.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy is characterized by microvascular insufficiency, which may lead to progressive heart failure. Accumulating evidence demonstrated a progressive reduction of the microvasculature in relation to the duration of diabetes (33, 48). Ang-1 is necessary for vessel stabilization (42). Our previous studies show that disruption of Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling contributes to diabetes-associated impairment of angiogenesis (8). Furthermore, upregulation of VEGF and apelin expression is associated with improvement of angiogenesis and cardiac function in post-MI db/db mice (6, 50). Previously, we also demonstrate that overexpression of Ang-1 attenuates diabetic cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in db/db mice (11). Our present data showed that apelin significantly increased Ang-1 and Tie-2 expression, which may contribute to attenuation of endothelial cell apoptosis and capillary regression in the hearts of db/db mice. In addition, we found that VEGFR2 expression was significantly reduced in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice. Interestingly, Tie-2 expression was not changed in the hearts of Sirt3KO mice. These data indicate that the regulation of VEGFR2 expression is through Sirt3 signaling pathway. Since Tie-2 expression was upregulated by apelin but was not affected by Sirt3, this may explain why knockout of Sirt3 could not completely abolish apelin-induced vessel sprouting. Blockade of VEGF has been shown to promote compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure in response to pressure overload (23). VEGF is significantly decreased in the heart of diabetes compared with nondiabetic heart (32). The expression of VEGF/VEGFR2 in response to myocardial ischemia or ischemia/reperfusion is also significantly impaired in diabetes (6, 31, 46). Our data showed that apelin gene therapy increased VEGF and VEGFR2 expression, enhanced myocardial vascular density, and improved cardiac function in diabetic db/db mice. Our findings suggest that apelin gene therapy may rescue diabetes-associated reduction of vascular density and cardiac dysfunction via activation of Sirt3 and upregulation of VEGF/VEGFR2 and Ang-1/Tie-2 expression.

Recent study shows that apelin treatment increases insulin sensitivity and improves glucose metabolism in db/db mice (49). In line with this study, we also found that apelin gene therapy significantly improved glucose levels in db/db mice during 6 wk of studies. There is no doubt that these effects of apelin gene therapy also contribute to the improvement of cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy. However, our present study did not address the long-term effects of apelin gene therapy on insulin action and glucose uptake in the hearts of diabetes. These studies are warranted to further investigation.

In summary, diabetic patients are strongly associated with cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, which constitutes a major and growing health burden in developed countries. Despite considerable treatment advances over that past two decades, the development of novel treatment for diabetic patients with heart failure remains a major priority. Apelin shows beneficial effects in the cardiovascular system and has recently been shown as a candidate therapeutic for treating chronic heart failure. The current study provides evidence that apelin gene therapy ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy. Our study further suggests that modification of Sirt3 could use as a novel therapy target for the treatment of diabetes-associated heart dysfunction and heart failure.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-102042 (to J. X. Chen).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: H.Z., X. He, X. Hou, and L.L. performed experiments; H.Z., X. He, X. Hou, and L.L. analyzed data; H.Z. and J.-X.C. interpreted results of experiments; H.Z. prepared figures; J.-X.C. conception and design of research; J.-X.C. drafted manuscript; J.-X.C. edited and revised manuscript; J.-X.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abaci A, Oguzhan A, Kahraman S, Eryol NK, Unal S, Arinc H, Ergin A. Effect of diabetes mellitus on formation of coronary collateral vessels. Circulation 99: 2239–2242, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellizzi D, Rose G, Cavalcante P, Covello G, Dato S, De RF, Greco V, Maggiolini M, Feraco E, Mari V, Franceschi C, Passarino G, De BG. A novel VNTR enhancer within the SIRT3 gene, a human homologue of SIR2, is associated with survival at oldest ages. Genomics 85: 258–263, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation 115: 3213–3223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caton PW, Richardson SJ, Kieswich J, Bugliani M, Holland ML, Marchetti P, Morgan NG, Yaqoob MM, Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Sirtuin 3 regulates mouse pancreatic beta cell function and is suppressed in pancreatic islets isolated from human type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 56: 1068–1077, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen JX, Lawrence ML, Cunningham G, Christman BW, Meyrick B. HSP90 and Akt modulate Ang-1-induced angiogenesis via NO in coronary artery endothelium. J Appl Physiol 96: 612–620, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen JX, Stinnett A. Ang-1 gene therapy inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha)-prolyl-4-hydroxylase-2, stabilizes HIF-1alpha expression, and normalizes immature vasculature in db/db mice. Diabetes 57: 3335–3343, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JX, Stinnett A. Critical role of the NADPH oxidase subunit p47(phox) on vascular TLR expression and neointimal lesion formation in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Lab Invest 88: 1316–1328, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JX, Stinnett A. Disruption of Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling contributes to the impaired myocardial vascular maturation and angiogenesis in type II diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1606–1613, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JX, Tuo Q, Liao DF, Zeng H. Inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase improves angiogenesis via enhancing Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling in diabetes. Exp Diabetes Res 2012: 836759, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JX, Zeng H, Lawrence ML, Blackwell TS, Meyrick B. Angiopoietin-1-induced angiogenesis is modulated by endothelial NADPH oxidase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1563–H1572, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JX, Zeng H, Reese J, Aschner JL, Meyrick B. Overexpression of angiopoietin-2 impairs myocardial angiogenesis and exacerbates cardiac fibrosis in the diabetic db/db mouse model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1003–H1012, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JX, Zeng H, Tuo QH, Yu H, Meyrick B, Aschner JL. NADPH oxidase modulates myocardial Akt, ERK1/2 activation and angiogenesis after hypoxia/reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1664–H1674, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou E, Suzuma I, Way KJ, Opland D, Clermont AC, Naruse K, Suzuma K, Bowling NL, Vlahos CJ, Aiello LP, King GL. Decreased cardiac expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in insulin-resistant and diabetic States: a possible explanation for impaired collateral formation in cardiac tissue. Circulation 105: 373–379, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhury M, Jonscher KR, Friedman JE. Reduced mitochondrial function in obesity-associated fatty liver: SIRT3 takes on the fat. Aging (Albany NY) 3: 175–178, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox CM, D'Agostino SL, Miller MK, Heimark RL, Krieg PA. Apelin, the ligand for the endothelial G-protein-coupled receptor, APJ, is a potent angiogenic factor required for normal vascular development of the frog embryo. Dev Biol 296: 177–189, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foldes G, Horkay F, Szokodi I, Vuolteenaho O, Ilves M, Lindstedt KA, Mayranpaa M, Sarman B, Seres L, Skoumal R, Lako-Futo Z, deChatel R, Ruskoaho H, Toth M. Circulating and cardiac levels of apelin, the novel ligand of the orphan receptor APJ, in patients with heart failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 308: 480–485, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foussal C, Lairez O, Calise D, Pathak A, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Valet P, Parini A, Kunduzova O. Activation of catalase by apelin prevents oxidative stress-linked cardiac hypertrophy. FEBS Lett 584: 2363–2370, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green MF, Hirschey MD. SIRT3 weighs heavily in the metabolic balance: a new role for SIRT3 in metabolic syndrome. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68: 105–107, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazarika S, Dokun AO, Li Y, Popel AS, Kontos CD, Annex BH. Impaired angiogenesis following hindlimb ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Differential regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 and soluble VEGFR-1. Circ Res 101: 948–956, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Jing E, Grueter CA, Collins AM, Aouizerat B, Stancakova A, Goetzman E, Lam MM, Schwer B, Stevens RD, Muehlbauer MJ, Kakar S, Bass NM, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Alt FW, Newgard CB, Farese RV, Jr, Kahn CR, Verdin E. SIRT3 deficiency and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation accelerate the development of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell 44: 177–190, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holash J, Maisonpierre PC, Compton D, Boland P, Alexander CR, Zagzag D, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ. Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science 284: 1994–1998, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holash J, Wiegand SJ, Yancopoulos GD. New model of tumor angiogenesis: dynamic balance between vessel regression and growth mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Oncogene 18: 5356–5362, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension 47: 887–893, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalin RE, Kretz MP, Meyer AM, Kispert A, Heppner FL, Brandli AW. Paracrine and autocrine mechanisms of apelin signaling govern embryonic and tumor angiogenesis. Dev Biol 305: 599–614, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HS, Patel K, Muldoon-Jacobs K, Bisht KS, Aykin-Burns N, Pennington JD, van der Meer R, Nguyen P, Savage J, Owens KM, Vassilopoulos A, Ozden O, Park SH, Singh KK, Abdulkadir SA, Spitz DR, Deng CX, Gius D. SIRT3 is a mitochondria-localized tumor suppressor required for maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and metabolism during stress. Cancer Cell 17: 41–52, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinz MJ, Davenport AP. Immunocytochemical localization of the endogenous vasoactive peptide apelin to human vascular and endocardial endothelial cells. Regul Pept 118: 119–125, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanza IR, Short DK, Short KR, Raghavakaimal S, Basu R, Joyner MJ, McConnell JP, Nair KS. Endurance exercise as a countermeasure for aging. Diabetes 57: 2933–2942, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DK, Cheng R, Nguyen T, Fan T, Kariyawasam AP, Liu Y, Osmond DH, George SR, O'Dowd BF. Characterization of apelin, the ligand for the APJ receptor. J Neurochem 74: 34–41, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Zeng H, Chen JX. Apelin-13 increases myocardial progenitor cells and improves repair postmyocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H605–H618, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Zeng H, Hou X, He X, Chen JX. Myocardial Injection of Apelin-Overexpressing Bone Marrow Cells Improves Cardiac Repair via Upregulation of Sirt3 after Myocardial Infarction. PLoS One 8: e71041, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marfella R, D'Amico M, Di FC, Piegari E, Nappo F, Esposito K, Berrino L, Rossi F, Giugliano D. Myocardial infarction in diabetic rats: role of hyperglycaemia on infarct size and early expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Diabetologia 45: 1172–1181, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marfella R, Esposito K, Nappo F, Siniscalchi M, Sasso FC, Portoghese M, Di Marino MP, Baldi A, Cuzzocrea S, Di FC, Barboso G, Baldi F, Rossi F, D'Amico M, Giugliano D. Expression of angiogenic factors during acute coronary syndromes in human type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53: 2383–2391, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messaoudi S, Milliez P, Samuel JL, Delcayre C. Cardiac aldosterone overexpression prevents harmful effects of diabetes in the mouse heart by preserving capillary density. FASEB J 23: 2176–2185, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palacios OM, Carmona JJ, Michan S, Chen KY, Manabe Y, Ward JL, III, Goodyear LJ, Tong Q. Diet and exercise signals regulate SIRT3 and activate AMPK and PGC-1alpha in skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY) 1: 771–783, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pillai VB, Sundaresan NR, Jeevanandam V, Gupta MP. Mitochondrial SIRT3 and heart disease. Cardiovasc Res 88: 250–256, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose G, Dato S, Altomare K, Bellizzi D, Garasto S, Greco V, Passarino G, Feraco E, Mari V, Barbi C, BonaFe M, Franceschi C, Tan Q, Boiko S, Yashin AI, De BG. Variability of the SIRT3 gene, human silent information regulator Sir2 homologue, and survivorship in the elderly. Exp Gerontol 38: 1065–1070, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sack MN. Emerging characterization of the role of SIRT3-mediated mitochondrial protein deacetylation in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H2191–H2197, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiojima I, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Schiekofer S, Ito M, Liao R, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Disruption of coordinated cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis contributes to the transition to heart failure. J Clin Invest 115: 2108–2118, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stratmann B, Gawlowski T, Tschoepe D. Diabetic cardiomyopathy–to take a long story serious. Herz 35: 161–168, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundaresan NR, Gupta M, Kim G, Rajamohan SB, Isbatan A, Gupta MP. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 2758–2771, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundaresan NR, Samant SA, Pillai VB, Rajamohan SB, Gupta MP. SIRT3 is a stress-responsive deacetylase in cardiomyocytes that protects cells from stress-mediated cell death by deacetylation of Ku70. Mol Cell Biol 28: 6384–6401, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suri C, Jones PF, Patan S, Bartunkova S, Maisonpierre PC, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD. Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell 87: 1171–1180, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szokodi I, Tavi P, Foldes G, Voutilainen-Myllyla S, Ilves M, Tokola H, Pikkarainen S, Piuhola J, Rysa J, Toth M, Ruskoaho H. Apelin, the novel endogenous ligand of the orphan receptor APJ, regulates cardiac contractility. Circ Res 91: 434–440, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanno M, Sakamoto J, Miura T, Shimamoto K, Horio Y. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1. J Biol Chem 282: 6823–6832, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tatemoto K, Hosoya M, Habata Y, Fujii R, Kakegawa T, Zou MX, Kawamata Y, Fukusumi S, Hinuma S, Kitada C, Kurokawa T, Onda H, Fujino M. Isolation and characterization of a novel endogenous peptide ligand for the human APJ receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 251: 471–476, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tuo QH, Zeng H, Stinnett A, Yu H, Aschner JL, Liao DF, Chen JX. Critical role of angiopoietins/Tie-2 in hyperglycemic exacerbation of myocardial infarction and impaired angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2547–H2557, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tziakas DN, Chalikias GK, Kaski JC. Epidemiology of the diabetic heart. Coron Artery Dis 16, Suppl 1: S3–S10, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon YS, Uchida S, Masuo O, Cejna M, Park JS, Gwon HC, Kirchmair R, Bahlman F, Walter D, Curry C, Hanley A, Isner JM, Losordo DW. Progressive attenuation of myocardial vascular endothelial growth factor expression is a seminal event in diabetic cardiomyopathy: restoration of microvascular homeostasis and recovery of cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy after replenishment of local vascular endothelial growth factor. Circulation 111: 2073–2085, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yue P, Jin H, illaud-Manzanera M, Deng AC, Azuma J, Asagami T, Kundu RK, Reaven GM, Quertermous T, Tsao PS. Apelin is necessary for the maintenance of insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E59–E67, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng H, Li L, Chen JX. Overexpression of angiopoietin-1 increases CD133+/c-kit+ cells and reduces myocardial apoptosis in db/db mouse infarcted hearts. PLoS One 7: e35905, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng XJ, Zhang LK, Wang HX, Lu LQ, Ma LQ, Tang CS. Apelin protects heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat. Peptides 30: 1144–1152, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng XX, Wilm TP, Sepich DS, Solnica-Krezel L. Apelin and its receptor control heart field formation during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev Cell 12: 391–402, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong JC, Huang Y, Yung LM, Lau CW, Leung FP, Wong WT, Lin SG, Yu XY. The novel peptide apelin regulates intrarenal artery tone in diabetic mice. Regul Pept 144: 109–114, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong JC, Yu XY, Huang Y, Yung LM, Lau CW, Lin SG. Apelin modulates aortic vascular tone via endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation pathway in diabetic mice. Cardiovasc Res 74: 388–395, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]