Abstract

Tuberculosis and lymphoma can share common features. We report the case of a non-HIV 60-year old man diagnosed with a severe form of disseminated tuberculosis in whom the atypical course of the disease under treatment led to investigations that unveiled the coexistence a non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This rare association has putative pathophysiological foundations. This justifies to raise the lymphoma hypothesis when a proved tuberculosis exhibits an atypical course.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Lymphoma, Splenomegaly

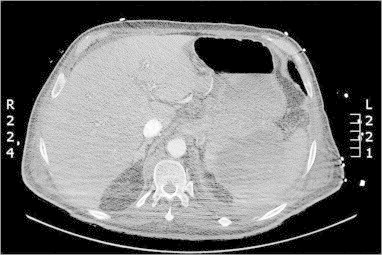

A 60-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a three month history of lethargy, weight loss, cough and night sweats. Upon admission, temperature was 37,2 °C, cardiac frequency was 80 bpm, respiratory frequency was 20/min, blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg and transcutaneous oxygen pulsed saturation was 97%. Physical examination was unremarkable (of note, no peripheral lymph nodes were found clinically). The patient had no personal or family history of tuberculosis. He was born in Turkey, and had lived in France for thirty years. The chest X-ray showed mediastinal enlargement without pulmonary infiltrates. The computed tomography evidenced large mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes as well as a hypodense spleen collection (Fig. 1). Full blood count, renal and liver function tests were unremarkable. HIV serology was negative. Because acid-fast stained bacilli were identified in a sputum sample (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), the diagnostic of tuberculosis was retained and a disseminated form suspected. Molecular analysis did not raise the suspicion of an antibiotic resistance. A quadruple therapy (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) was started, followed by some clinical improvement. Two weeks later, the patient presented a relapse of fever and asthenia. New bacteriological samples were analyzed (blood cultures, broncho-alveolar lavage) without results. A second CT revealed that the mediastinal lymph nodes had decreased in size while the spleen was still enlarged with a necrotic aspect (Fig. 1). Splenectomy was decided to prevent the risk of fistula into the peritoneum. The pathological examination of the spleen revealed a non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and chemotherapy was started. The patient died shortly after of septic shock, and no follow-up CT could be performed.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomography revealing necrotic splenomegaly.

This case report is an occasion to remind that the principle of parsimony that is a backbone of medical reasoning is not an absolute dogma. In some cases, a disease may hide another one. TB and lymphoma can share similar clinical and radiological features, which may make the differential diagnosis a challenge. In a recent report, three patients with a presumed diagnosis of TB on clinical grounds (without bacteriological confirmation) were eventually diagnosed with a Hodgkin disease in two cases, and with a diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the other case.1 Several reports have described the coexistence of tuberculosis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in lymph nodes.2 Of importance, TB and lymphoma can be causatively related, through the well established lymphoma-related immunosuppression.3,4 In the other direction, it has been reported that the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is significantly increased (OR 1.8) in individuals with a history of TB.5 The risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is increased in individuals with a history of severe forms of tuberculosis who have not received curative chemotherapy,6 and an underlying common susceptibility has been postulated. In our patient, the relapse of fever two weeks after the initiation of treatment occurred too early for the possible diagnosis of a paradoxical reaction to have been likely. This type of reaction tends to happen later during the course of treatment, especially in non-HIV-patients.7,8 In absence of documented nosocomial infection, it appeared logical to consider the diagnosis of extensive caseous necrosis of the spleen and that of a lymphoma. Because of the poor diagnostic performances of fine needle aspiration cytology of the spleen9,10 and because of the risk associated with the intraperitoneal rupture of a massive caseous abscess, a splenectomy was performed that unveiled the coexistence of tuberculosis and the lymphoma.

The diagnosis of lymphoma should be considered among the possible explanations of the atypical evolution of a diagnosed TB under treatment, especially in the absence of arguments for antibiotic resistance.

References

- 1.Sellar R.S., Corbett E.L., D'Sa S., Linch D.C., Ardeshna K.M. Treatment for lymph node tuberculosis. BMJ. 2010 Mar;340:c63. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellido M.C., Martino R., Martinez C., Sureda A., Brunet S. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: coexistence in an abdominal lymph node. Haematologica. 1995 Sep–Oct;80(5):482–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan M.H., Armstrong D., Rosen P. Tuberculosis complicating neoplastic disease. A review of 201 cases. Cancer. 1974 Mar;33(3):850–858. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197403)33:3<850::aid-cncr2820330334>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa L.J., Gallafrio C.T., Franca F.O., del Giglio A. Simultaneous occurrence of Hodgkin disease and tuberculosis: report of three cases. South Med J. 2004 Jul;97(7):696–698. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200407000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavani A., La Vecchia C., Franceschi S., Serraino D., Carbone A. Medical history and risk of Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000 Feb;9(1):59–64. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askling J., Ekbom A. Risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma following tuberculosis. Br. J. Cancer. 2001 Jan;84(1):113–115. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breen R.A., Smith C.J., Bettinson H., Dart S., Bannister B., Johnson M.A. Paradoxical reactions during tuberculosis treatment in patients with and without HIV co-infection. Thorax. 2004 Aug;59(8):704–707. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter E.J., Mates S. Sudden enlargement of a deep cervical lymph node during and after treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest. 1994 Dec;106(6):1896–1898. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suri R., Gupta S., Gupta S.K., Singh K., Suri S. Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology in abdominal tuberculosis. Br J Radiol. 1998 Jul;71(847):723–727. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.847.9771382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kercher K.W., Matthews B.D., Walsh R.M., Sing R.F., Backus C.L., Heniford B.T. Laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly. Am J Surg. 2002 Feb;183(2):192–196. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00874-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]