Abstract

Neurons and endocrine cells use a complex array of signaling molecules to communicate with each other and with various targets. The majority of these signaling molecules are stored in specialized organelles awaiting release on demand: 40–60 nm vesicles carry conventional or small molecule neurotransmitters, and 200–400 nm granules contain bioactive peptides. The supply of small molecule neurotransmitters is tightly regulated by local feedback of synthetic rates and transport processes at sites of release. The larger granules that contain bioactive peptides present the secretory cell with special challenges, since the peptide precursors are inserted into the lumen of the secretory pathway in the cell soma and undergo biosynthetic processing while being transported to distant sites for eventual secretion. One solution to this dilemma in information handling has been to employ proteolytic cleavage of secretory granule membrane proteins to produce cytosolic fragments that can signal to the nucleus, affecting gene expression. The use of regulated intramembrane proteolysis to signal from secretory granules to the nucleus is compared to its much better understood role in relaying information from the endoplasmic reticulum by SREBP and ATF6 and from the plasma membrane by Cadherins, Notch and ErbB4.

I. Conventional or small molecule neurotransmitters

At chemical synapses, neurons communicate by releasing synaptic vesicles filled with small molecule neurotransmitters such as glutamate, acetylcholine and norepinephrine, as well as secretory granules filled with neuropeptides. These neurotransmitters bind their cognate receptors on the postsynaptic neuron or nearby target cells and elicit changes in their electrical properties and in intracellular signaling cascades. The steps involved in neurotransmitter use include biosynthesis, packaging, release and removal. The synthesis of small molecule neurotransmitters is catalyzed by enzymes that are made in the neuronal cell body and trafficked to the nerve terminal by slow axonal transport (Fig. 1A). For example, conversion of tyrosine into dopa, the precursor to dopamine and norepinephrine, requires tyrosine hydroxylase and the synthesis of acetylcholine requires choline acetyltransferase. Essential precursors may be brought into the terminal by plasma membrane transporters located in the pre-synaptic membrane (tyrosine and choline) or may be produced by resident mitochondria (acetyl CoA).

Figure 1. Synaptic vesicle and secretory granule formation and release.

A. Neurons utilize both SVs (blue) and SGs (yellow) to communicate; the vacuolar ATPase is involved in the acidification of both compartments. SGs can be released from axons and from dendrites. The synthesis of acetylcholine (ACh) from choline and AcCoA occurs in the presynaptic cytosol and is catalyzed by choline acetyltransferase (ChAT). The vesicular ACh transporter and plasma membrane choline transporter are shown; local control of choline uptake, ACh synthesis and vesicular packaging allow rapid adjustments to local conditions. B. Schematic showing formation of immature SGs by budding from the TGN. Removal of non-secretory granule proteins and membrane remodeling by clathrin coated vesicles occurs as immature SGs mature. The vesicles that bud from immature SGs can give rise to constitutive-like secretion or can be returned to the TGN. Secretion from constitutive-like vesicles is modulated by two Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (Rho-GEFs), Kalirin and Trio. Mature secretory granules are formed by further acidification and can release their contents in response to secretagogue stimulation. The regulated secretory pathway is different from the constitutive pathway, in which vesicles that bud from the TGN fuse with the plasma membrane and do not require any stimulus for exocytosis.

The small molecule neurotransmitters are packaged into 40–60 nm diameter vesicles, powered by specific vesicular transporters that use the electrochemical driving force generated by the vacuolar ATPase to concentrate transmitter in the vesicles (Albers et al. 2012). The synaptic vesicles are then released in response to Ca2+ influx triggered by the arrival of action potentials. Release of neuropeptide-containing secretory granules generally requires higher frequency stimulation than release of synaptic vesicles. Signaling by small molecule neurotransmitters is terminated by their hydrolysis (acetylcholinesterase), presynaptic uptake and re-use (norepinephrine) or uptake and re-use or metabolism (glutamate). The recycling of synaptic vesicle membrane proteins is controlled locally; vesicular membrane retrieved from the cell surface is used again to form vesicles which are refilled with cytosolic neurotransmitter. Elegant local regulatory mechanisms allow precise control of the supply of small molecule neurotransmitter in response to events within the nerve terminal as well as the surrounding environment. For example, the plasma membrane transporter needed to retrieve the choline produced in the synaptic cleft when acetylcholine is hydrolyzed by acetylcholinesterase is packaged into the synaptic vesicles that contain acetylcholine (Fig.1A) (Albers et al. 2012). An increase in cytosolic levels of norepinephrine potently inhibits tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the conversion of tyrosine to dopa (Spector et al. 1967). Since neuropeptides are synthesized in the cell soma, different regulatory mechanisms must be called into play.

II. Peptides have a different lifestyle

Neurons and endocrine cells have the capacity to synthesize neuropeptides and efficiently store them in secretory granules (SG), which are also referred to as large dense core vesicles. A distinguishing feature of these 200–400 nm diameter membrane delimited organelles is their electron density, which reflects their high content of protein (Fava et al. 2012). The interior of the secretory granule is topologically equivalent to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum and to extracellular space (Fig. 1B). Neuropeptides are encoded by more than a hundred separate genes and are initially synthesized as inactive precursors (Mains & Eipper 2012). These preprohormones and other soluble proteins of the regulated secretory pathway are guided into the lumen of the secretory pathway by the interaction of their N-terminal signal sequences with the signal recognition particle and the ER translocon. Some peptide precursors require the formation of essential disulfide bonds and modifications like N-glycosylation, O-glycosylation, sulfation and phosphorylation (Markoff et al. 1988;Unsworth et al. 1982). These modifications are carried out by machinery common to all eukaryotic cells. Like other soluble secretory proteins, peptide precursors are subject to the quality control systems that monitor the lumen of the ER. Synthesis of a misfolded mutant proinsulin triggers a stress response in the ER and impairs trafficking of wildtype proinsulin, leading to β-cell failure and diabetes mellitus, as seen in the Akita mouse (Araki et al. 2003;Hodish et al. 2010). Similarly, isolated growth hormone deficiency type II reflects the autosomal dominant effect of misfolded mutant growth hormone on wildtype growth hormone synthesized at the same time (Lochmatter et al. 2010).

The propeptides exit the ER and transit through the Golgi complex, undergoing post-translational modifications encoded by their primary sequences. After these newly synthesized proteins traverse the Golgi complex, they are packaged into immature secretory granules (Fig. 1B). Immature secretory granules can be distinguished from mature secretory granules by their location, their elevated luminal pH and their inability to respond to secretagogues. Immature secretory granules must undergo a maturation process during which they are subject to acidification and membrane remodeling (Morvan & Tooze 2008). Mature secretory granules are specialized structures that have the ability to release their content upon high frequency stimulation (Mains & Eipper 2012). This feature distinguishes the regulated secretory pathway from the constitutive pathway, where vesicles carrying cargo bud from the trans-Golgi network and rapidly fuse with the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B). The vesicles that bud from immature secretory granules during the maturation process carry content that contributes to the constitutive-like secretory pathway; material retrieved from immature secretory granules is not stored and can return to the TGN or reach the plasma membrane directly or indirectly.

The propeptides synthesized in the ER are generally inactive and must undergo a series of highly conserved steps before they become mature bioactive molecules (Fig. 2). The first step is usually endoproteolytic cleavage at pairs of basic or single basic residues and is often carried out by the subtilisin-like prohormone convertases (PCs) and a limited number of other endoproteases (Seidah et al. 1993). These cleavages normally occur in the acidic lumen of the immature SGs and result in the release of product peptides that are not yet bioactive. Removal of the C-terminal basic amino acids exposed by prohormone convertase mediated cleavage is generally accomplished by carboxypeptidase E (Fricker & Leiter 1999). In one of the final steps, when a C-terminal glycine residue is exposed, the penultimate amino acid is often α-amidated (Eipper et al. 1992b). Additionally, some peptides undergo N-terminal acetylation, Tyr sulfation and enzymatic conversion of N-terminal Gln into pyroglutamic acid (Beinfeld 2003;Buczek et al. 2005;Schilling et al. 2003). These modifications are often essential to generate bioactive peptides that are capable of binding to their cognate receptors with high affinity (Cuttitta 1993;In et al. 2001;Merkler 1994).

Figure 2. Processing of neuropeptides.

Neuropeptides are synthesized as inactive precursors; their NH2-terminal signal sequences are removed co-translationally and the precursors generally travel through the Golgi complex and exit the TGN before they are cleaved by prohormone convertases at pairs of basic residues. The C-terminal basic residues exposed are removed by Carboxypeptidase E (CPE), often generating a glycine extended peptide. PAM catalyzes the two-step amidation reaction that generates bioactive amidated peptide hormones. The three major splice variants of PAM are shown; the two catalytic domains of PAM are separated by exon 16 in PAM-1 and the transmembrane domain present in PAM-1 and PAM-2 is spliced out of PAM-3.

Secretory granules must be transported to their sites of release, which can be many millimeters up to a meter removed from their site of synthesis, and must then undergo the multiple steps involved in controlled fusion of the granule membrane with the plasma membrane. Although partial release of secretory granule content has been observed (Lindau 2011), neuropeptides are not retrieved after exocytosis and secretory granules cannot be refilled. Unlike the synaptic vesicles that contain small molecule neurotransmitters, peptidergic granules cannot be reloaded locally. So an obvious question occurs: how does the cell sense events occurring in the lumen of the secretory granules or assess the size of its granule pool? Is there a feedback signal that can turn on expression of the appropriate genes upon granule depletion or deal with errors in the final stages of peptide processing? Proteins that span the secretory granule membrane are candidates to play a role in such a signaling process.

III. Peptide amidation: Peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM)

PAM, a type I integral membrane protein that functions late in the peptide biosynthetic pathway, is thought to participate in a signaling process of this type. PAM is the only enzyme known to catalyze the α-amidation of peptides (Eipper et al. 1992b). It is a bifunctional enzyme that carries out amidation in a two step process (Fig. 2). The enzymatic domains of PAM include peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM; E.C.1.14.17.3) and peptidyl-α-hydroxyglycine α-amidating lyase (PAL; E.C.4.3.2.5). In the first step, PHM carries out a hydroxylation reaction at the α-carbon of the terminal glycine in the presence of copper while consuming ascorbate and molecular oxygen, yielding a peptidyl-α-hydroxyglycine intermediate. PAL then carries out the dealkylation of the intermediate, leaving the carboxamide moiety at the C-terminus of the peptide and producing glyoxylate. PAM has a highly conserved non-catalytic cytosolic domain that affects both the entry of PAM into SGs and its trafficking through the endocytic pathway.

In mammals, PAM transcripts are alternatively spliced, yielding at least seven different PAM proteins in a tissue-specific and developmentally regulated manner (Eipper et al. 1992a;Milgram et al. 1992). The integral membrane forms of PAM include PAM-1, where the PHM and PAL domains are separated by an approximately 10 kDa linker region encoded by optional exon 16 (initially called Exon A); PAL is followed by the transmembrane and cytosolic domains (Fig. 2). Deletion of exon 16 generates PAM-2. Soluble isoforms of PAM lack the transmembrane domain but include the carboxy-terminal domain. PAM-4, a rarely expressed soluble monofunctional enzyme, consists of PHM, exon 16 and an additional unique 20 residues from read through into the following intron, but does not include PAL or a transmembrane domain (Eipper et al. 1992a).

The prohormone convertases in the SG lumen cleave PAM-1 at pairs of basic residues, producing soluble PHM, soluble PAL and bifunctional soluble PAM (PAMs) (Fig. 3); even the octapeptide generated by cleavage at the Lys-Arg sequence that precedes the PHM domain has been identified in tissue lysates (Pan et al. 2006). PAM-2, which lacks the cleavage site in exon 16, produces a soluble PAM protein that lacks exon 16. Membrane forms of PAL (PALm) and transmembrane domain-cytosolic domain fragments (TMD-CD) are formed as a result of these cleavages (Fig. 3). These membrane proteins reach the plasma membrane during exocytosis and undergo endocytosis. At steady state, less than 2% of the PAM-1 in corticotrope tumor cells is on the plasma membrane

Figure 3. PAM is subject to cleavage by secretory granule enzymes.

AtT-20 cells express proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and produce products characteristic of anterior pituitary corticotropes. Endogenous levels of PAM in AtT-20 cells are much lower than pituitary levels; PAM trafficking has been studied by stably expressing single isoforms of PAM and PAM mutants in AtT-20 cells. PAM-1 can be proteolytically processed in the lumen of the SG by the prohormone convertases to generate soluble PHM, membrane PAL (PALm) or soluble, bifunctional PAMs. The soluble proteins are released upon exocytosis while the membrane proteins [PAM-1, PALm and transmembrane domain-cytosolic domain (TMD-CD)] are inserted into the plasma membrane. They are quickly endocytosed and can be cleaved by endoproteases in the endocytic pathway, degraded in lysosomes or returned to the TGN for re-entry into SGs. Peptide products stored in the SGs (represented by gold balls) are released in response to stimulation.

IIIa. The PAM cytosolic domain is essential for trafficking

The 86 residue PAM cytosolic domain has features characteristic of unstructured domains - low hydrophobicity, high net charge, sensitivity to proteases and phosphorylation at multiple sites (Husten et al. 1993;Steveson et al. 1999;Steveson et al. 2001;Yun et al. 1995). More than one third of all proteins have intrinsically unstructured domains, which play important regulatory roles in diverse pathways like endocytosis, cell cycle regulation and transcription (Kalthoff et al. 2002;Tompa 2002). These flexible regions are involved in specific, but readily reversible, interactions (Hsu et al. 2004;Jonker et al. 2006;Nash et al. 2001). Binding of these pliable proteins with their interactors is accompanied by a change in local conformation (Aivazian & Stern 2000;Dyson & Wright 2002), facilitating cooperativity and intermolecular interactions.

The cytosolic domain of PAM contains the routing information necessary for granule entry and endocytic trafficking (Fig. 4). A truncation mutant, PAM-1/899, which includes the TMD but only 9 amino acids of the CD, is a fully active amidating enzyme, but is localized on the plasma membrane instead of in secretory granules and fails to undergo internalization (Milgram et al. 1993;Tausk et al. 1992). Exogenously expressed epitope-tagged PAM-TMD/CD (858–976), which lacks both luminal catalytic domains, follows an itinerary similar to that of full-length PAM. It localizes to the TGN in AtT-20 cells and to secretory granules in primary pituitary cells (Fig. 4). A chimeric protein comprised of the luminal domain of the Interleukin 2 receptor α-chain (Tac), a plasma membrane protein, and PAM TMD/CD, adopts the subcellular localization of PAM (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The PAM cytosolic domain regulates trafficking in the secretory and endocytic pathways.

PAM entry into SGs is facilitated by phosphorylation of its cytosolic domain. Truncation of the cytosolic domain, generating PAM-1/899, reduces accumulation in granules and prevents endocytosis. The extracellular domain of a heterologous type I surface protein, Tac, when fused to the PAM cytosolic domain to generate a chimeric molecule, is routed to secretory granules. While soluble granule proteins are released upon exocytosis, granule membrane proteins are recycled. After traversing the early endosomes, PAM enters multivesicular bodies (MVBs), sorting centers where proteins are either targeted for degradation or recycled. Surface biotinylation, a direct method of tracking an endocytosed molecule, indicates that plasma membrane PAM can be returned to SGs. Dephosphorylation of specific sites in the cytosolic domain of PAM is essential for its entry into the intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) that characterize MVBs and its return to the TGN. Phosphomimetic mutants of PAM-1 (PAM-1/S937D and PAM-1/S949D) accumulate in endocytic compartments and fail to collect in the perinuclear region like wild type PAM-1.

Two dimensional gel electrophoresis and proteomic analyses revealed extensive phosphorylation of the cytosolic domain of PAM in anterior pituitary and in corticotrope cell lines (Rajagopal et al. 2009). Recombinant PAM-CD is phosphorylated by protein kinase A (Ser921), protein kinase C (Ser932 and Ser937) (Yun et al. 1995) and casein kinase II (Thr946 and Ser949) (Steveson et al. 2001). The biological roles of phosphorylation at Ser937 (a PKC site) (Yun et al. 1995) and Ser949 (a Uhmk1 and casein kinase II site) (Caldwell et al. 1999) (Steveson et al. 2001) were analyzed using phospho-specific antisera and cell lines expressing phosphomimetic (Ser to Asp) or non-phosphorylatable (Ser to Ala) mutants of PAM (Steveson et al. 1999;Steveson et al. 2001). As observed for furin (Schapiro et al. 2004) and the cation independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (Wan et al. 1998), specific steps in PAM trafficking are regulated by cytosolic domain phosphorylation.

Although Ser937 can be phosphorylated in the ER, early trafficking events are not affected by phosphorylation at this site (Steveson et al. 1999). PAM-1/S937A was more rapidly degraded and yielded less PHM secreted via the constitutive-like pathway. A phosphomimetic mutation at this site (PAM-1/S937D) was without effect on biosynthetic trafficking (Fig. 4). Based on antibody internalization experiments, PAM-1/S937A was preferentially routed to lysosomes (Yun et al. 1995) whereas PAM-1/S937D remained localized in a late endocytic compartment and failed to return to the TGN. Both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation at Ser937 are required for proper trafficking of PAM (Fig. 4). Stimulation of PKC by treatment of cells with phorbol myristate acetate yielded increased phosphorylation of Ser937; the increase was most apparent in vesicles near the cell surface and in the TGN area (Steveson et al. 1999).

PAM phosphorylated at Ser949 is localized in the perinuclear region. Stably transfected AtT-20 cell lines expressing PAM-1 Thr946Ser949 to Ala946,949 (PAM/TS/AA) or PAM-1 Thr946Ser949 to Asp946,949 (PAM/TS/DD) were used to analyze the role of phosphorylation at these sites in trafficking through the regulated secretory pathway and the endocytic pathway (Steveson et al. 2001). PAM/TS/DD entered immature secretory granules more readily, generating more soluble PHM that was stored in mature granules and could be secreted in response to secretagogue (Fig. 4). In contrast, PAM/TS/AA entered immature granules inefficiently and was more rapidly degraded. Based on antibody uptake experiments, neither PAM/TS/AA nor PAM/TS/DD returned to the TGN (Fig. 4). Electron microscopic examination indicated that PAM-1/TS/DD accumulated on the limiting membrane of multivesicular bodies while PAM-1/TS/AA and PAM-1 were readily identified in intraluminal vesicles (Bäck et al. 2010). Surface biotinylation revealed that PAM-1/TS/AA, which generated a soluble bifunctional PAM protein (PAMs) (Fig. 3), returned to secretory granules more efficiently than PAM-1/TS/DD, which yielded very little PAMs.

The trafficking of furin, an endoprotease with homology to members of the prohormone convertase family, and a type I integral membrane protein, revealed key features of immature secretory granule formation (Thomas 2002). Although furin enters immature SGs, it is excluded from mature granules, returning to the TGN as immature secretory granule membrane remodeling occurs. Furin also cycles between the plasma membrane and endosomes. For furin, endosome to TGN retrieval is directed by binding of phospho-furin acidic cluster binding protein (PACS-1) to the CKII phosphorylation sites in the furin carboxy-terminal domain (Wan et al. 1998). This interaction facilitates AP-1-mediated transport of furin from the endosomes to the TGN. PACS-1 also controls the endosome to TGN trafficking of several acidic cluster containing membrane proteins including the cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR) and carboxypeptidase D (CPD) (Thomas 2002). Although the cytosolic domain of PAM contains an acidic cluster, this region is not essential for PAM trafficking (Steveson et al. 2001).

IIIb. PAM as a luminal sensor

Initial characterization of PAM-1 solubilized from atrial membranes revealed a several fold increase in specific activity upon proteolytic removal of its non-catalytic COOH-terminal region (Husten & Eipper 1991). In PAM-3, a naturally occurring isoform which lacks the transmembrane domain, the COOH-terminal region that is exposed to the cytosol as part of PAM-1, is present in the SG lumen (Fig. 2). The PHM activity of purified PAM-3 was similarly increased when its COOH-terminal region was removed (Husten et al. 1993). Conformational constraints in intact PAM mean that PHM activity can reflect changes in the C-terminal domain.

Corticotrope cell lines expressing PAM-1 and PALm exhibited unexpected alterations in their ability to package the products of proopiomelanocortin processing into secretory granules and store them for secretagogue-stimulated release. Expression of soluble PHM or soluble PAL did not produce a similar response, but expression of myc-TMD/CD altered cytoskeletal organization in a manner similar to that of full length PAM (El Meskini et al. 2001). Using an AtT-20 cell line in which expression of PAM-1 could be increased in response to addition of doxycycline to the culture medium, it was shown that expression of PAM-1 altered cytoskeletal organization, blocked the endoproteolytic processing of luminal proteins, caused secretory granules to accumulate in the perinuclear region instead of at the tips of processes and diminished the ability of secretagogues to stimulate ACTH release (Ciccotosto et al. 1999).

These observations led us to search for PAM-CD interactors using a yeast two-hybrid screen. Using PAM-CD as the “bait” and a trafficking incompetent PAM-CD mutant as the control, four P-CIPs (PAM COOH-terminal Interactor Proteins) were identified: P-CIP1 (RASSF9), P-CIP2 (Uhmk1), P-CIP10 (Kalirin) and Trio (Alam et al. 1996). RASSF9, a member of the Ras-association domain family, is thought to play a role in endocytosis (Chen et al. 1998). Uhmk1, a Ser/Thr protein kinase followed by a RNA binding domain, phosphorylates PAM at Ser949 (Caldwell et al. 1999) and cycles between the cytosol and the nucleus (Boehm et al. 2002). Kalirin and Trio are cytosolic proteins with nine spectrin-like repeats, two Dbl homology domains and multiple protein/protein and protein/lipid interaction domains; they are GDP/GTP exchange factors (GEFs) for multiple Rho family GTPases (Alam et al. 1997;Mains et al. 1999). Their first GEF domain activates both Rac1 and RhoG while their second GEF domain activates RhoA. Kalirin and Trio interact with PAM-CD through their spectrin-like repeat regions. These interactors provide multiple pathways through which PAM could relay information about the luminal milieu to cytosolic machinery.

IIIc. Lessons from PAM knock-outs

The role of PAM in vivo was assessed by targeted deletion of PHM in Drosophila (Jiang et al. 2000) and PAM in mouse (Czyzyk et al. 2005). In Drosophila, disruption of the PHM gene completely eliminated PHM activity in larvae and resulted in embryonic lethality. PHM null flies completed larval development but failed to hatch. They failed to produce amidated peptides but were morphologically relatively normal. Rescue experiments using PHM expression under the control of a heat shock promoter revealed an essential role for PHM expression during early development (Jiang et al. 2000).

Elimination of the PAM gene in mice resulted in embryonic lethality (Czyzyk et al. 2005). Development proceeded fairly normally until embryonic day 12.5. At this time, PAM−/− embryos developed edema, probably due to cardiovascular deficits. The PAM−/− embryos died in utero between embryonic days 14.5 and 15.5. No PHM or PAL enzymatic activity was detectable in PAM null embryos. Mice heterozygous for the PAM gene (PAM+/−) developed normally. Despite having only half the wild type level of PHM and PAL activity, levels of amidated Joining Peptide and amidated αMSH, two products of proopiomelanocortin processing, were unchanged (Czyzyk et al. 2005). A quantitative peptidomic study revealed only a small increase in the amount of peptidylglycine intermediate detectable in the PAM+/− pituitary (Yin et al. 2011). Thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) terminates with an amidated Pro; although substrates terminating in –Pro-Gly are especially poor PAM substrates (Merkler 1994), only a small increase in TRH-Gly levels was observed in the hypothalamus of PAM+/− mice (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2009). Half the normal level of PAM appears to be sufficient to sustain close to normal levels of peptide amidation.

Despite this fact, PAM+/− mice exhibited a number of deficits. Older PAM+/− mice showed an increase in adiposity and mild glucose intolerance (Czyzyk et al. 2005). Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis regulation was altered; TSHβ mRNA levels increased less in PAM+/− than in WT mice in response to hypothyroidism (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2009). PAM+/− mice were unable to vasoconstrict their peripheral vasculature in response to cold and thus unable to maintain body temperature in the cold. They showed an increase in anxiety-like behavior and an increase in seizure sensitivity (Bousquet-Moore et al. 2009). Recent studies showed that the PAM+/− mice were also deficient in short- and long-term contextual and cued fear conditioning (Gaier et al, unpublished). Electrophysiological studies comparing synaptic transmission in slices of amygdala from PAM+/− and wildtype mice revealed deficits in inhibitory GABAergic transmission (Gaier et al. 2010). These deficits could cause enhanced evoked and spontaneous excitatory signals in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala in PAM+/− animals, contributing to the behavioral deficits observed.

The deficits observed in PAM+/− mice, despite a very limited decline in peptide amidation, led us to explore non-catalytic roles for this integral membrane protein. Based on studies identifying signaling pathways that relay information about the ER lumen to the nucleus [Fig. 5; sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6)], we searched for a soluble fragment generated from the cytosolic domain of PAM that could serve as a signaling molecule communicating information from the secretory granule to the nucleus. Studies of cytosolic fragments generated from amyloid precursor protein (APP), Notch and ICA512 also informed our studies of PAM.

Figure 5. Generation of soluble signals from membrane proteins.

Examples of membrane proteins whose cleavage generates a soluble fragment which is targeted to the nucleus and known to regulate gene transcription. Sterol regulatory element binding protein [SREBP and bHLH; (Brown & Goldstein 2009)]; activating transcription factor 6 [ATF6 and bZIP; (Kohno 2010)]; amyloid precursor protein [APP and AICD; (Cao & Sudhof 2001;Thinakaran & Koo 2008)]; Notch and NICD (Kopan & Ilagan 2009); islet cell autoantigen 512 (ICA512 and CCF); PAM-1 and sf-CD (Rajagopal et al. 2010). Cleavages: black arrow, intramembrane; blue arrow, α-secretase-like; pink arrow, S1P; red arrow, prohormone convertase; turquoise arrow, calpain.

IIId. γ-Secretase-mediated release of sf-CD

The treatment of PAM-1 or Myc-TMD-CD expressing cells with proteasomal inhibitors revealed the presence of a soluble, cytosolic 16 kDa fragment that was recognized by an antibody specific for the last 12 residues of the PAM C-terminal tail (Fig. 5). This soluble fragment of the PAM cytosolic domain (sf-CD) was more efficiently produced from Myc-TMD-CD than from PAM-1 and its formation was blocked upon treatment of cells with a γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT or L685458). Cleavage by γ-secretase typically requires prior removal of the luminal/extracellular domain to permit access of substrate to the γ-secretase active site. Consistent with this, relatively little sf-CD is generated from PAM-2, which does not undergo extensive luminal cleavage. For PAM-1, prohormone convertase mediated cleavage at the Lys-Lys822 site immediately following PAL leaves a 44 residue luminal stalk attached to the TMD/CD, generating a protein that could serve as a substrate for γ-secretase.

Outside of the regulated secretory pathway, PAM-1 is subject to a juxtamembrane cleavage that generates a potential γ-secretase substrate with a shorter stalk (Fig. 5). A variety of type 1 integral membrane proteins are subject to proteolytic shedding, which removes a large extracellular fragment of the substrate protein and is usually carried out by proteases that are members of the “a disintegrin and metalloprotease” (ADAM) family (Beel & Sanders 2008;Wolfe & Kopan 2004). Use of inhibitors suggests that α-secretase cleaves PAM-1 in this manner although the cleavage site has not yet been identified. Rapid endocytosis means that less than 2% of the PAM-1 resides on the plasma membrane at steady state. It is not yet known if the longer stalk left after prohormone convertase cleavage of PAM must undergo additional proteolysis to generate a γ-secretase substrate. Attempts to determine the N-terminus of sf-CD suggested multiple sites of cleavage near the middle of the transmembrane domain (Rajagopal et al. 2010).

Mutations in the cytosolic domain of PAM-1 affect the extent to which it is cleaved by γ-secretase. This could reflect altered protein trafficking or an altered structure. Neither PAM-1/TS/DD, PAM-1/S937D, nor PAM-1 with five phosphomimetic mutations in its cytosolic domain (PAM-1/5P) generate as much sf-CD as PAM-1. A mutation that eliminates the interaction of PAM-CD with Kalirin and with Uhmk1 generates more than the normal amount of sf-CD. The active γ-secretase complex is thought to localize to the plasma membrane as well as in endocytic compartments. PAM-1 that is rapidly endocytosed from the cell surface could be cleaved in an endocytic compartment. A PAM-1 mutant that fails to enter the intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (PAM/TS/DD) may have limited access to the protease, which might explain the diminished sf-CD content of cells stably expressing this PAM mutant (Bäck et al. 2010).

IV. Signals mediated by regulated intramembrane proteolysis

Regulated intramembrane proteolysis of membrane proteins in various subcellular locations, generating smaller cytosolic signaling molecules has emerged as a novel signal transduction mechanism regulating processes as diverse as cellular differentiation, the unfolded protein response and cell adhesion (Fig. 5). Over the past decade several membrane embedded proteases have been identified: S2P cleaves SREBP and ATF6; γ-Secretase cleaves Notch, ErbB4, Cadherin and APP; Rhomboids cleave Spitz; and signal peptide peptidase (SPP) clears remnant signal peptides from the membrane (Wolfe 2009;Wolfe & Kopan 2004). These intramembrane cleaving proteases carry out hydrolysis of their substrates within a transmembrane domain.

Presenilin (PS), a nine-pass transmembrane protein, is the catalytic component of the γ-secretase complex (Beel & Sanders 2008), which is responsible for the intramembrane proteolysis of PAM. Generation of the γ-secretase substrate is often triggered by ligand binding or dimerization and is therefore part of a signaling cascade. Several substrates of the γ-secretase complex have been identified but there is little sequence conservation at the cleavage site. There is also significant variability in the optimal length of the ectodomain stalks, which are typically 20–30 residues long, but can be as short as 12 residues, as in the case of Notch (Kopan & Ilagan 2009;Steiner et al. 2008). Prokaryotes contain proteases that are evolutionarily related to those present in animal cells (Brown et al. 2000). Despite their ability to function within the membrane, their catalytic mechanisms are very similar to those of proteases that function in an aqueous environment (Wolfe & Kopan 2004).

The three other components of this unusual aspartyl protease are also integral membrane proteins: nicastrin, Aph-1 and Pen-2 are all required for activity both in vivo and in vitro. Assembly of this complex is thought to occur early in the secretory pathway. Nicastrin and Aph-1 assemble first, followed by association of PS. The interaction of Pen-2 with PS enables PS to undergo auto-endoproteolysis, forming an N-terminal fragment (NTF)-C-terminal fragment (CTF) heterodimer (Beel & Sanders 2008). The NTF-CTF heterodimer is the catalytic component of the active protease. The subcellular localization of the complex is controversial, although studies suggest that plasma membrane and endosomes are the major sites of γ-secretase mediated proteolysis (Kaether et al. 2006). The proteins cleaved by γ-secretase must generally shed their ectodomains before they can be cleaved by γ-secretase. This unique membrane protease is not thought to require helix destabilizing residues for proteolysis, contributing to its versatility in recognition and cleavage of substrates.

The coordinated functioning of a multi-component complex biological unit like the cell must include inter-organellar communication. Such communication is generally initiated by a set of molecules or complexes that can sense a change in the internal environmental cues of the organelle and transmit a cascade of signaling events involving several different effector systems (Sallese et al. 2009). These signals activate effector proteins either by altering gene transcription, translation or post-translational modifications like phosphorylation. Here we discuss examples of membrane proteins that undergo regulated intramembrane proteolysis in response to changes in the environmental milieu.

IVa. Signaling from the Endoplasmic Reticulum

Cholesterol sensing – SREBP

SREBP binds to the promoter region of the LDL receptor gene, making it sensitive to sterol regulated transcription (Brown & Goldstein 2009). An ER membrane protein, SREBP is involved in feedback regulation of lipid and sterol synthesis (Fig. 6A). It consists of an N-terminal basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) leucine zipper domain that binds DNA and activates transcription, two transmembrane domains connected by a short luminal loop and a regulatory domain that binds SREBP cleavage activating protein (SCAP). SCAP, a membrane protein with eight membrane spanning regions, also binds insulin induced gene (Insig) (Brown & Goldstein 2009;Goldstein et al. 2006), a six transmembrane helix protein. Insig binds cholesterol-bound SCAP, retaining the cholesterol-SCAP-SREBP complex in the ER when cellular cholesterol levels are high (Fig. 6A). When cells are depleted of sterols, SCAP associates with COP II coat proteins, allowing the SCAP-SREBP complex to enter COP II coated vesicles and move from the ER to the Golgi complex (Brown & Goldstein 2009). In the Golgi complex, SREBP is cleaved in a two-step process. Proteolysis is initiated by the Site-1 protease (S1P), a subtilisin-related membrane-tethered protease located in the Golgi complex that cleaves the luminal loop of SREBP (Fig. 6A). Another Golgi protease, Site-2 protease (S2P), can then release the N-terminal bHLH leucine zipper domain of SREBP by cleaving within the adjacent transmembrane domain (Brown et al. 2000). The bHLH domain with three hydrophobic residues at its C-terminus is released from the membrane into the cytosol. This fragment of SREBP then enters the nucleus, where it activates expression of genes involved in lipid synthesis and uptake (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP) of SREBP and ATF6 in response to sterols and unfolded proteins.

A. In cells depleted of sterols, SCAP transports SREBP from the ER to the Golgi in COP II vesicles. In the Golgi, the luminal loop of SREBP is cleaved by S1P, separating its two transmembrane domains. In the Golgi, S2P cleaves the N-terminal fragment of SREBP in its transmembrane domain to liberate the bHLH leucine zipper domain, which translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of genes involved in lipid synthesis and uptake. B. In unstressed cells, ATF6 is retained in the ER bound to the chaperone BiP. When unfolded proteins accumulate and bind to BiP, ATF6 lacking BiP translocates to the Golgi complex where it is cleaved sequentially by the same two proteases, S1P and S2P, to release a fragment containing a bZip transcription factor domain. This fragment translocates to the nucleus and activates genes involved in the unfolded protein response pathway.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) - ATF6

Eukaryotic cells regulate the capacity of the ER to fold and traffic proteins (Scheuner & Kaufman 2008); this is a particularly important response in professional secretory cells, which synthesize large amounts of secreted proteins. The ER contains signaling proteins that are activated by the presence of unfolded proteins in its lumen (Fig. 6B). The response involves suppression of translation, up-regulation of chaperone expression as well as induction of degradation of misfolded and aggregated proteins (Scheuner & Kaufman 2008). The presence of unfolded proteins in the ER is sensed by three proteins, ATF6, inositol requiring protein 1 α (IRE1α) and dsRNA activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK) (Ron & Walter 2007). At steady state, binding Ig protein (BiP), a luminal chaperone protein, interacts with each of the three UPR sensors. Upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, BiP dissociates from these sensors, leading to activation of the pathway.

PERK is activated following dimerization and autophosphorylation. Activated PERK phosphorylates eIF2α, leading to a reduction in translation. IRE1α also undergoes dimerization, activating its endoribonuclease activity. Activated IRE1α then cleaves Xbp1 mRNA, allowing it to be spliced into an mRNA that encodes X-box binding protein 1(XBP1s). IRE1α also degrades some cellular mRNAs to reduce the protein load in the ER. ATF6 is a type II membrane protein with a basic leucine zipper transcriptional activation domain (bZip) in its cytosolic N-terminal region (Scheuner & Kaufman 2008). The accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER causes dissociation of BiP from ATF6 (Fig. 6B). Dissociation of BiP causes a conformational change that permits packaging of ATF6 into COP II vesicles for trafficking to the Golgi complex. In the Golgi complex, sequential proteolysis by S1P and S2P takes place, as for SREBP, releasing the 50 kDa transcriptionally active N-terminal cytosolic domain (bZip) (Ron & Walter 2007). ATF6, along with XBP1s, induces expression of chaperones and the ER associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery. These pathways play a key role in the response of β-cells to expression of mutant proinsulins (Khoo et al. 2011).

IVb. Signaling from the plasma membrane

Cell-cell adhesion - Cadherin

Cadherins are type I integral membrane glycoproteins that mediate calcium dependent cell-cell adhesion. Epithelial or E-cadherin is important for tissue morphogenesis, wound healing and the maintenance of tissue integrity (Maretzky et al. 2005). Neuronal or N-cadherin is important for synaptic function and plasticity (Rubio et al. 2005). Presenilin facilitates the maturation and trafficking of N-cadherin to the cell surface (Parks & Curtis 2007). Additionally, presenilin concentrates at synaptic and epithelial cell adherens junctions that include p-120, α-catenin and β-catenin. Presenilin interacts with and stabilizes the cadherin-catenin complex and its association with the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 7) (Parks & Curtis 2007). Calcium-influx-induced ectodomain cleavage of E-cadherin by a metalloprotease is followed by intramembrane cleavage of E-cadherin by the γ-secretase complex and disassembly of the adherens junction (Maretzky et al. 2005). N-cadherin cleavage by ADAM 10 is thought to be triggered by calcium influx through the NMDA receptor, producing a γ-secretase substrate (Fig. 7) (Marambaud et al. 2003;Uemura et al. 2006b). The cytoplasmic fragments (CTFs) generated by γ-secretase cleavage of the cadherins carry out multiple functions. For example, the N-cadherin CTF (N-cad/CTF2) binds to CREB binding protein (CBP) in the cytoplasm, promoting its ubiquitylation and degradation. This causes the displacement of CBP from the transcription initiation complexes formed at cAMP-response-element containing promoters, repressing transcription of those genes (Marambaud et al. 2003). The disassembly of adherens junctions releases β-catenin into the cytoplasm (Fig. 7). Translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus promotes transcription of Wnt target genes (Hass et al. 2009;Parks & Curtis 2007;Uemura et al. 2006a). In addition, fluorescence energy transfer (FRET) experiments suggest a close association of N-cad/CTF2 with β-catenin in the nucleus. N-cad/CTF2 promotes β-catenin stability by preventing its phosphorylation dependent degradation and increases transcription of the gene encoding β-catenin. Transcription of the gene encoding N-cadherin is reduced by N-cad/CTF2 (Parks & Curtis 2007).

Figure 7. Signaling to the nucleus by γ-secretase mediated cleavage of N-Cadherin.

N-Cadherin undergoes a sheddase cleavage at the cell surface in response to cell dissociation or membrane depolarization. This is followed by a γ-secretase (γ) cleavage that generates a soluble cytosolic fragment, N-cad/CTF2, which binds to CREB binding protein (CBP). This interaction promotes CBP ubiquitylation and degradation (small green boxes), down-regulating transcription that is dependent on cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB). N-cad/CTF2 also translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with β-catenin and regulates gene expression. γ-secretase also stabilizes the adherens junctions formed by cadherin and the catenins (α, β and p120). When these junctions disassemble, β-catenin (β) is released and can localize to the nucleus and regulate target gene expression.

Notch

Notch, a type I membrane protein, is involved in mediating short-range communication between cells during development and in the adult (Kopan & Ilagan 2009). Notch signaling requires contact between cells and can promote or suppress cell proliferation, cell death, determination of cell fate and differentiation (Kopan & Ilagan 2009). The Notch receptor is glycosylated, cleaved by furin and then targeted to the cell surface as a heterodimer held together by non-covalent interactions. Receptor activation begins upon binding to ligand present on a neighboring cell. Ligand binding promotes juxtamembrane Notch cleavage by ADAM metalloproteases, generating a membrane anchored fragment called NEXT (Fig. 8). This fragment is a substrate for the γ-secretase complex, which cleaves several sites in its transmembrane domain, releasing Notch intracellular domain, NICD. The most stable product begins at Val1744 (NICD-V) and contains 4 residues of the transmembrane domain (Kopan & Ilagan 2009). The identity of the subcellular compartment in which cleavage occurs is controversial. However, NEXT cleavage is not thought to be endocytosis dependent, which suggests that shedding occurs on the cell surface (Kopan & Ilagan 2009). Endocytosis is thought to be required for NICD generation as an endocytic mutant of Notch failed to form NICD (Kopan & Ilagan 2009). However, cell impermeant γ-secretase inhibitors block NICD formation (Kopan & Ilagan 2009), indicating that NICD forms at the plasma membrane or in early endosomes (Fig. 8). NICD then translocates to the nucleus, associates with the protein CBF-1, Su(H), Lag-1 (CSL) and activates transcription of target genes such as hairy/enhancer of split (Hes) and subfamily of Hes, related with YRPW motif (Hey), GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3), CD25, c-myc and cyclin D1 (Borggrefe & Oswald 2009;Kopan & Ilagan 2009).

Figure 8. Signaling to the nucleus by γ-secretase mediated cleavage of ErbB4 and Notch.

ErbB4 and Notch first undergo sheddase cleavage at the cell surface in response to binding their ligands, neuregulin and Delta or Jagged, respectively. Shedding of the extracellular domain of Notch generates a membrane anchored fragment called NEXT. This is followed by γ-secretase cleavage at the cell surface or, in the case of Notch, also in endosomes, generating a soluble fragment, E4ICD from ErbB4 and NICD from Notch. The soluble fragments translocate to the nucleus and regulate gene expression.

ErbB4

ErbB4 is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) of the EGF receptor family (Sardi et al. 2006). RTKs are known to signal through their ligand-activated tyrosine kinase domains. In addition, ErbB4 signals directly to the nucleus in response to binding to its ligand, neuregulin. Along with receptor phosphorylation, ligand binding stimulates intramembrane proteolysis and nuclear translocation of the resulting intracellular domain (E4ICD) (Lee et al. 2002;Ni et al. 2001). Ligand binding first promotes ectodomain cleavage by ADAM 17, allowing γ-secretase mediated cleavage and release of E4ICD into the cytosol (Fig. 8). Interestingly, ErbB4 has two splice variants, juxtamembrane a and b (JM a and b), that differ in the extracellular juxtamembrane region and in their susceptibility to cleavage. The JMa isoform, which is capable of signaling by regulated intramembrane proteolysis, is enriched in brain, conferring tissue specific signaling capability to the molecule (Sardi et al. 2006). In the brain, E4ICD produced by neuregulin-induced cleavage of ErbB4 forms a complex with TAK1 binding protein 2 (TAB2) and nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR). In neural precursor cells, this complex translocates to the nucleus and inhibits differentiation into astrocytes by repressing glial gene transcription (Sardi et al. 2006). ErbB4 signaling is also required for lactogenesis and differentiation of the murine mammary gland. As in the brain, a transcriptional role for the E4ICD fragment was demonstrated in breast epithelium, where it was shown to associate with STAT5A, a transcription factor, to facilitate β-casein expression (Hass et al. 2009).

V. Signaling from secretory granules

Balancing SG demand and supply

In response to a very strong set of secretagogues, anterior pituitary endocrine cells can release half of their secretory granules in under an hour. It is not yet clear how the supply of SGs is replenished. Neurons are faced with the added burden of transporting SGs produced in the cell soma to a distant presynaptic ending or distal dendrite. The membrane spanning proteins found in mature SGs are in a position to 1) relay information about the status of the SG lumen to the cytosol, indicating the readiness of the SGs for secretion, and 2) report on the status of the total SG pool during stimulated exocytosis. Based on other organelle signaling pathways, one would predict a role for both transcriptional and translational control in the cellular response to SG depletion or accumulation.

Genetic analysis of neuroendocrine PC12 cell lines +that have lost the ability to generate SGs (Grundschober et al. 2002), and studies of the expression patterns in MIN-6 insulinoma cells stimulated with glucose (Webb et al. 2000), uncovered roles for several genes involved in signaling, transcription, translation and secretion. Therefore it is likely that multiple gene products orchestrate the complex program needed to achieve neurosecretory competence in professional secretory cells. In Drosophila, DIMM, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, has been shown to coordinate the characteristics of neuroendocrine cells. Six target genes have been shown to be directly controlled by DIMM. RNA interference and mass-spectroscopic analysis identified three targets to be critical for DIMM function; one of these targets is PHM, the amidating enzyme (Park et al. 2011).

SGs are diverse in terms of their hormone content: hypothalamic neurons store vasopressin and oxytocin, β-cells store insulin, and corticotropes store the products of proopiomelanocortin processing. Nevertheless, SG assembly in each of these very different cell types involves many of the same steps. Assembly of new SGs involves the coordinate control of transcription and translation, successful protein folding, assembly of membrane components, sorting of SG proteins and lipids from non-granule components, granule maturation and trafficking of the SGs to their sites of release. During prolonged stimulation, SGs can be depleted, making it essential to couple exocytosis to the induction of SG production.

PAM

The discovery of a γ-secretase mediated cleavage that generates cytosolic sf-CD from PAM raised the possibility the sf-CD could affect the cytosolic trafficking machinery or enter the nucleus and affect gene transcription. The subcellular localization of PAM sf-CD was analyzed by microinjecting fluorescently tagged recombinant protein into neuroendocrine cells and neurons. Fluorescently tagged PAM-CD quickly left the cytosol, accumulating in the nucleus over a 12 min period (Francone et al. 2010). Consistent with this observation, isolation of nuclei from the atrium of the heart and the anterior pituitary revealed the presence of endogenous PAM sf-CD. Immunostaining of isolated nuclei revealed specked staining concentrated on the nuclear membrane along with diffuse nuclear staining (Rajagopal et al. 2009).

To understand the signal that causes sf-CD generation, primary pituitary cells were subjected to repeated stimulation known to be intense enough to deplete the cells of secretory granules. The sf-CD content of the cells increased in response to repeated stimulation (Rajagopal et al. 2010). While sf-CD in primary anterior pituitary cultures can be detected without the addition of proteasomal inhibitors, detection of sf-CD in AtT20-cells stably expressing PAM-1 or Myc-TMD-CD requires addition of proteasomal inhibitors. Taken together our data indicate that sf-CD plays an important signaling role in sensing the depletion of secretory granules and relaying that information to the nucleus to turn on gene expression.

Uhmk1, the Ser/Thr kinase that interacts with PAM-CD and phosphorylates it at Ser949, has an effect on the nuclear localization of PAM-CD. Uhmk1 normally shuttles between the cytosol and the nucleus, with nuclear levels exceeding cytosolic levels (Francone et al. 2010). When co-expressed in AtT-20 cells, active Uhmk1reduced the nuclear pool of PAM-CD while the kinase inactive mutant Uhmk1K54A had no effect. Even when tethered to the membrane, transiently expressed Uhmk1 reduced the nuclear pool of PAM-CD (Francone et al. 2010). These results are consistent with the decreased nuclear accumulation of PAM-CD bearing phosphomimetic mutations. To understand the role of PAM mediated gene expression, a doxycycline inducible PAM-1 cell line was analyzed to identify genes up-regulated by PAM-CD. Slpi, a protease inhibitor, and aquaporin 1 (Aqp1) were up-regulated 9.5-fold and 3-fold, respectively (Francone et al. 2010). Aqp1, a water channel, has been shown to play an important role in secretory granule biogenesis (Arnaoutova et al. 2008). Consistent with these changes, expression of both Slpi and Aqp1 was reduced in PAM+/− mice (6.6-fold and 12-fold, respectively). Aqp1 protein levels increased in cells transiently transfected with Myc-CD and decreased in cells expressing Uhmk1 (Francone et al. 2010).

ICA512/PTPRN

Islet cell autoantigen 512 (ICA512), which is also known as Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Receptor Type N (PTPRN) and as islet antigen-2 (IA-2), lacks phosphatase activity due to amino acid substitutions at critical sites in its protein tyrosine phosphatase domain (Fig. 9). ICA512 localizes to SGs in neuroendocrine cells and has been especially well studied in the insulin-secreting β-cells of the endocrine pancreas (Solimena et al. 1996). ICA512 is a type 1 integral membrane protein consisting of a 576 amino acid luminal domain, a 23 amino acid transmembrane domain and a 380 amino acid cytoplasmic domain. Phogrin, which is also known as Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Receptor Type N2 (PTPRN2) and as islet antigen 2β (IA-2β), another SG membrane protein, shares 76% identity with ICA512 in its cytosolic domain and only 26% identity in its luminal domain (Zhang et al. 2007). The first 200 luminal residues of phogrin also share homology to regulated endocrine-specific protein of 18 kDa (RESP18), which was identified as a SG luminal protein in pancreatic islets (Zhang et al. 2007).

Figure 9. Regulation of the secretory granule pool by granule membrane protein ICA512/PTPRN.

Studies on β-cells have led to an understanding of signaling by the SG membrane protein ICA512. This protein has no known role in the lumen of the granules. However, when Ca2+ entry triggers granule exocytosis, the ICA512 that arrives on the cell surface undergoes a μ-calpain-mediated cleavage to generate a soluble fragment, ICA512-CCF. ICA512-CCF has two functions. By binding signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5), it regulates expression of several genes encoding SG proteins. In the cytosol, ICA512-CCF dimerizes with intact ICA512, releasing the granules from their interaction with the cytoskeleton, increasing their mobility and increasing their probability of exocytosis.

ICA512 over-expression in insulin-secreting MIN6 cells increased their insulin content and the number of SGs by 3-fold (Harashima et al. 2005). Targeted disruption of either ICA512 (Saeki et al. 2002) or Phogrin (Kubosaki et al. 2004) impaired insulin secretion and promoted glucose intolerance (Henquin et al. 2008). In mice lacking both ICA512 and Phogrin, the insulin content of the endocrine pancreas was reduced 45% compared to wild type mice and global defects in neuroendocrine secretion were observed (Henquin et al. 2008). The double knockout mice also exhibited changes an anxiety-like behavior, impairments in conditioned learning and an increase in spontaneous and induced seizures (Nishimura et al. 2009).

In response to glucose stimulation, ICA512 present in the membranes of insulin-containing SGs reaches the plasma membrane (Fig. 9). It is here that the cytosolic domain of ICA512 is cleaved by μ-calpain, generating ICA512-CCF, a soluble cytosolic fragment (Trajkovski et al. 2004). This fragment translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) to enhance transcription of the gene encoding preproinsulin and selected SG genes including prohormone convertase 1/3, CPE and ICA512 itself (Mziaut et al. 2006). Over-expression of ICA512-CCF increased levels of cyclin D1 and D2 and increased INS-1 cell proliferation (Mziaut et al. 2008). In addition to its effects on gene expression ICA512 plays a role in granule trafficking. While resident in mature SGs, full-length ICA512 interacts with the F-actin associated protein β2-syntrophin, immobilizing the SGs. Soluble ICA512-CCF modulates SG mobility during stimulated secretion by interacting with the corresponding region of intact ICA512 in granules and displacing it from β2-syntrophin (Fig. 9) (Trajkovski et al. 2008).

Chromogranin A (CgA)

CgA has been identified as a “granulogenic” protein since it promotes the aggregation and sorting of SG proteins (Koshimizu et al. 2010) (Fig. 10). Separate from this role, CgA has been reported to regulate SG production in endocrine and neuroendocrine cells (Kim et al. 2001;Koshimizu et al. 2010). Previous studies have shown an up-regulation of CgA transcription upon secretagogue stimulation of chromaffin cells (Tang et al. 1997). PC12 pheochromocytoma cells stably transfected with antisense constructs to reduce CgA levels had a marked decrease in SG number (Kim et al. 2001). Since CgA is a soluble secretory granule protein, its effects on granule biogenesis cannot be mediated by release of an active cytosolic fragment.

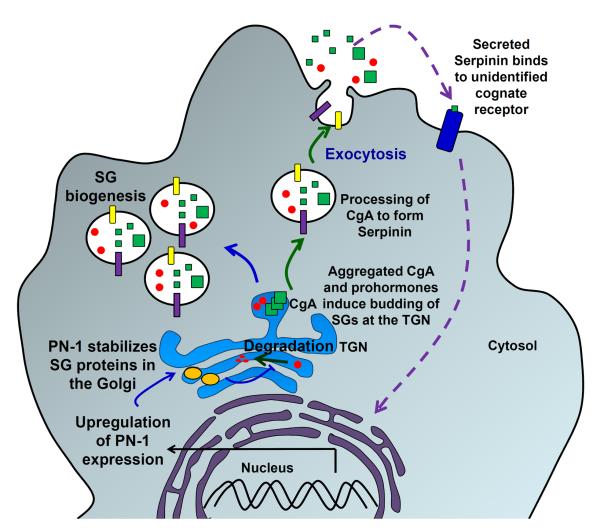

Figure 10. Regulation of secretory granule production by CgA.

CgA is a soluble SG protein that aggregates (big green cubes) in the TGN and is thought to induce SG formation. CgA can be processed by prohormone convertases to form smaller peptides (small green cubes). One peptide derived from CgA, serpinin, is thought to bind to a receptor on the cell surface, initiating a signaling cascade that results in up-regulation of a protease inhibitor, protease nexin 1 (PN-1). PN-1 prevents degradation of SG proteins (red dots) in the Golgi complex and thereby increases the number of SGs produced.

6T3 cells, obtained by the fusion of AtT-20 cells with mouse myeloma cells, lack a regulated secretory pathway; CgA expression in these cells caused the formation of SGs (Kim & Loh 2006). Blocking ER to Golgi protein trafficking in wildtype 6T3 cells with Brefeldin A allowed recovery of SG proteins and demonstrated that SG protein degradation occurred in the Golgi complex in these cells (Kim & Loh 2006). The granules formed in CgA over-expressing PC12 cells respond to secretagogue by releasing CgA as well as exogenously expressed POMC (Kim et al. 2001). Microarray analysis of CgA-overexpressing 6T3 cells identified Protease Nexin 1 (PN-1), a serine protease inhibitor localized in the Golgi apparatus, as up-regulated in these cells (Fig. 10). Over-expression of PN-1 in wild type 6T3 cells prevented the degradation of SG proteins (Kim & Loh 2006). Conversely, depletion of PN-1 by expression of antisense RNA to PN-1 in CgA-over-expressing 6T3 cells resulted in enhanced degradation of SG proteins. Thus CgA is thought to up-regulate SG formation in part by preventing the degradation of SG proteins in the Golgi complex. Further analysis identified a CgA derived C-terminal peptide, serpinin, as the mediator of this effect (Koshimizu et al. 2010). It is proposed that during stimulated secretion, CgA derived peptides that are released bind to a putative receptor or binding protein that up-regulates transcription and translation of PN-1 (Fig. 10).

VI. Concluding thoughts

As an integral membrane protein that carries out one of the final modifications of peptide processing, PAM is placed in an opportune position to act as a SG signaling molecule. Its cytosolic domain, which plays an essential trafficking role, has features resembling intrinsically unstructured domains and has been shown to be multiply phosphorylated and proteolytically sensitive. Several molecules including SREBP, ATF6, Cadherins, Notch and ErbB4 are cleaved by proteases to generate smaller fragments that translocate to the nucleus and activate gene transcription. The relative importance of PAM as an intracellular signaling molecule, compared to other homeostatic mechanisms, remains for the future.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Interest This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-32949, DK-32948, the Janice and Rodney Reynolds Fund, and the William Beecher Scoville Fund.

References

- Aivazian D, Stern LJ. Phosphorylation of T cell receptor zeta is regulated by a lipid dependent folding transition. Nature Struct Biol. 2000;7:1023–1026. doi: 10.1038/80930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MR, Caldwell BD, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Novel proteins that interact with the COOH-terminal cytosolic routing determinants of an integral membrane peptide-processing enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28636–28640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MR, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Hand TA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin, a cytosolic protein with spectrin-like and GDP/GTP exchange factor-like domains that interacts with peptidylglycine a-amidating monooxygenase, an integral membrane peptide-processing enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12667–12675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers RW, Siegel GJ, Xiw ZJ. In Basic Neurochemistry Principles of Molecular, Cellular and Medical Neurobiology. 8 ed Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. Membrane Transport; pp. 40–62. [Google Scholar]

- Araki E, Oyadomari S, Mori M. Impact of endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway on pancreatic beta-cells and diabetes mellitus. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:1213–1217. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutova I, Cawley NX, Patel N, Kim T, Rathod T, Loh YP. Aquaporin 1 is important for maintaining secretory granule biogenesis in endocrine cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1924–1934. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäck N, Rajagopal C, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Secretory granule membrane protein recycles through multivesicular bodies. Traffic. 2010;11:972–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beel AJ, Sanders CR. Substrate specificity of gamma-secretase and other intramembrane proteases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1311–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7462-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinfeld MC. Biosynthesis and processing of pro CCK: recent progress and future challenges. Life Sci. 2003;72:747–757. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Yoshimoto T, Crook MF, Nallamshetty S, True A, Nabel GJ, Nabel EG. A growth factor-dependent nuclear kinase phosphorylates p27(Kip1) and regulates cell cycle progression. EMBO J. 2002;21:3390–3401. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borggrefe T, Oswald F. The Notch signaling pathway: transcriptional regulation at Notch target genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1631–1646. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8668-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Moore D, Ma XM, Nillni EA, Czyzyk TA, Pintar JE, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Reversal of physiological deficits caused by diminished levels of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase by dietary copper. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1739–1747. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Cholesterol feedback: from Schoenheimer's bottle to Scap's MELADL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S15–S27. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800054-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Ye J, Rawson RB, Goldstein JL. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell. 2000;100:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek O, Bulaj G, Olivera BM. Conotoxins and the posttranslational modification of secreted gene products. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:3067–3079. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BD, Darlington DN, Penzes P, Johnson RC, Eipper BA, Mains RE. The Novel Kinase P-CIP2 Interacts with the Cytosolic Routing Determinants of the Peptide Processing Enzyme Peptidylglycine a-Amidating Monooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34646–34656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science. 2001;293:115–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1058783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Johnson RC, Milgram SL. P-CIP1, a novel protein that interacts with the cytosolic domain of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase, is associated with endosomes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33524–33532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccotosto GD, Schiller MR, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Induction of integral membrane PAM expression in AtT-20 cells alters the storage and trafficking of POMC and PC1. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:459–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttitta F. Peptide amidation: signature of bioactivity. Anat Rec. 1993;236:87–3. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk TA, Ning Y, Hsu MS, Peng B, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Pintar JE. Deletion of peptide amidation enzymatic activity leads to edema and embryonic lethality in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2005;287:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson JH, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper BA, Green CBR, Campbell TA, Stoffers DA, Keutmann HT, Mains RE, Ouafik LH. Alternative splicing and endoproteolytic processing generate tissue-specific forms of PAM. J Biol Chem. 1992a;267:4008–4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper BA, Stoffers DA, Mains RE. The biosynthesis of neuropeptides: peptide alpha-amidation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992b;15:57–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Meskini R, Galano GJ, Marx R, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Targeting of Membrane Proteins to the Regulated Secretory Pathway in Anterior Pituitary Endocrine Cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3384–3393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava E, Dehghany J, Ouwendijk J, Muller A, Niederlein A, Verkade P, Meyer-Hermann M, Solimena M. Novel standards in the measurement of rat insulin granules combining electron microscopy, high-content image analysis and in silico modelling. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1013–1023. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francone VP, Ifrim MF, Rajagopal C, Wang Y, Carson JH, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Signaling from the secretory granule to the nucleus: PAM and P-CIP2. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1543–1548. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker LD, Leiter EH. Peptides, enzymes and obesity: new insights from a `dead' enzyme. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:390–393. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaier ED, Rodriguiz RM, Ma XM, Sivaramakrishnan S, Bousquet-Moore D, Wetsel WC, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Haploinsufficiency in peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase leads to altered synaptic transmission in the amygdala and impaired emotional responses. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13656–13669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2200-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Bose-Boyd RA, Brown MS. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundschober C, Malosio ML, Astolfi L, Giordano T, Nef P, Meldolesi J. Neurosecretion competence. A comprehensive gene expression program identified in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36715–36724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima S, Clark A, Christie MR, Notkins AL. The dense core transmembrane vesicle protein IA-2 is a regulator of vesicle number and insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8704–8709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408887102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass MR, Sato C, Kopan R, Zhao G. Presenilin: RIP and beyond. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC, Nenquin M, Szollosi A, Kubosaki A, Notkins AL. Insulin secretion in islets from mice with a double knockout for the dense core vesicle proteins islet antigen-2 (IA-2) and IA-2beta. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:573–581. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodish I, Liu M, Rajpal G, Larkin D, Holz RW, Adams A, Liu L, Arvan P. Misfolded proinsulin affects bystander proinsulin in neonatal diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:685–694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JM, Lee YC, Yu CT, Huang CY. Fbx7 functions in the SCF complex regulating Cdk1-cyclin B-phosphorylated hepatoma up-regulated protein (HURP) proteolysis by a proline-rich region. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32592–32602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten EJ, Eipper BA. The membrane-bound bifunctional peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase protein. Exploration of its domain structure through limited proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17004–17010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten EJ, Tausk FA, Keutmann HT, Eipper BA. Use of endoproteases to identify catalytic domains, linker regions and functional interactions in soluble PAM. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9709–9717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In Y, Fujii M, Sasada Y, Ishida T. Structural studies on C-amidated amino acids and peptides: structures of hydrochloride salts of C-amidated Ile, Val, Thr, Ser, Met, Trp, Gln and Arg, and comparison with their C-unamidated counterparts. Acta Crystallogr B. 2001;57:72–81. doi: 10.1107/s0108768100013975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Kolhekar AS, Jacobs PS, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Taghert PH. PHM is required for normal developmental transitions and for biosynthesis of secretory peptides in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2000;226:118–136. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker HR, Wechselberger RW, Pinkse M, Kaptein R, Folkers GE. Gradual phosphorylation regulates PC4 coactivator function. FEBS J. 2006;273:1430–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaether C, Schmitt S, Willem M, Haass C. Amyloid precursor protein and Notch intracellular domains are generated after transport of their precursors to the cell surface. Traffic. 2006;7:408–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalthoff C, lves J, Urbanke C, Knorr R, Ungewickell EJ. Unusual structural organization of the endocytic proteins AP180 and epsin 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8209–8216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo C, Yang J, Rajpal G, Wang Y, Liu J, Arvan P, Stoffers DA. Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin-1-like beta (ERO1lbeta) regulates susceptibility to endoplasmic reticulum stress and is induced by insulin flux in beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2599–2608. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Loh YP. Protease nexin-1 promotes secretory granule biogenesis by preventing granule protein degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:789–798. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Tao-Cheng JH, Eiden LE, Loh YP. Chromogranin A, an “on/off” switch controlling dense-core secretory granule biogenesis. Cell. 2001;106:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno K. Stress-sensing mechanisms in the unfolded protein response: similarities and differences between yeast and mammals. J Biochem. 2010;147:27–33. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshimizu H, Kim T, Cawley NX, Loh YP. Chromogranin A: a new proposal for trafficking, processing and induction of granule biogenesis. Regul Pept. 2010;160:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubosaki A, Gross S, Miura J, Saeki K, Zhu M, Nakamura S, Hendriks W, Notkins AL. Targeted disruption of the IA-2beta gene causes glucose intolerance and impairs insulin secretion but does not prevent the development of diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2004;53:1684–1691. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Jung KM, Huang YZ, Bennett LB, Lee JS, Mei L, Kim TW. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase-like intramembrane cleavage of ErbB4. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6318–6323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau M. High resolution electrophysiological techniques for the study of calcium-activated exocytosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochmatter D, Strom M, Eble A, Petkovic V, Fluck CE, Bidlingmaier M, Robinson IC, Mullis PE. Isolated GH deficiency type II: knockdown of the harmful Delta3GH recovers wt-GH secretion in rat tumor pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4400–4409. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Eipper BA. Peptides. In: Brady ST, et al., editors. In Basic Neurochemistry Principles of Molecular, Cellular and Medical Neurobiology. 8 ed Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. pp. 390–406. [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Alam MR, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Back N, Hand TA, Eipper BA. Kalirin, a Multifunctional PAM COOH-terminal Domain Interactor Protein, Affects Cytoskeletal Organization and ACTH Secretion from AtT-20 Cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2929–2937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P, Wen PH, Dutt A, Shioi J, Takashima A, Siman R, Robakis NK. A CBP binding transcriptional repressor produced by the PS1/epsilon-cleavage of N-cadherin is inhibited by PS1 FAD mutations. Cell. 2003;114:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretzky T, Reiss K, Ludwig A, Buchholz J, Scholz F, Proksch E, De SB, Hartmann D, Saftig P. ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion, migration, and beta-catenin translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9182–9187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoff E, Sigel MB, Lacour N, Seavey BK, Friesen HG, Lewis UJ. Glycosylation selectively alters the biological activity of prolactin. Endocrinology. 1988;123:1303–1306. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-3-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkler DJ. C-terminal amidated peptides: production by the in vitro enzymatic amidation of glycine-extended peptides and the importance of the amide to bioactivity. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1994;16:450–456. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram SL, Johnson RC, Mains RE. Expression of individual forms of peptidylglycine a-amidating monooxygenase in AtT-20 cells: endoproteolytic processing and routing to secretory granules. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:717–728. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.4.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram SL, Mains RE, Eipper BA. COOH-terminal signals mediate the trafficking of a peptide processing enzyme in endocrine cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:23–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morvan J, Tooze SA. Discovery and progress in our understanding of the regulated secretory pathway in neuroendocrine cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mziaut H, Kersting S, Knoch KP, Fan WH, Trajkovski M, Erdmann K, Bergert H, Ehehalt F, Saeger HD, Solimena M. ICA512 signaling enhances pancreatic beta-cell proliferation by regulating cyclins D through STATs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:674–679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710931105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mziaut H, Trajkovski M, Kersting S, Ehninger A, Altkruger A, Lemaitre RP, Schmidt D, Saeger HD, Lee MS, Drechsel DN, Muller S, Solimena M. Synergy of glucose and growth hormone signalling in islet cells through ICA512 and STAT5. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:435–445. doi: 10.1038/ncb1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash P, Tang X, Orlicky S, Chen Q, Gertler FB, Mendenhall MD, Sicheri F, Pawson T, Tyers M. Multisite phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor sets a threshold for the onset of DNA replication. Nature. 2001;414:514–521. doi: 10.1038/35107009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni CY, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Carpenter G. gamma -Secretase cleavage and nuclear localization of ErbB-4 receptor tyrosine kinase. Science. 2001;294:2179–2181. doi: 10.1126/science.1065412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Kubosaki A, Ito Y, Notkins AL. Disturbances in the secretion of neurotransmitters in IA-2/IA-2beta null mice: changes in behavior, learning and lifespan. Neuroscience. 2009;159:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Che FY, Peng B, Steiner DF, Pintar JE, Fricker LD. The role of prohormone convertase-2 in hypothalamic neuropeptide processing: a quantitative neuropeptidomic study. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1763–1777. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Hadzic T, Yin P, Rusch J, Abruzzi K, Rosbash M, Skeath JB, Panda S, Sweedler JV, Taghert PH. Molecular organization of Drosophila neuroendocrine cells by Dimmed. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1515–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]