Abstract

Purpose of review

We aim to discuss current insights into our understanding of the mechanisms by which socioeconomic status (SES) influences the prevalence and severity of asthma in ethnic minorities. In addition, we review potential risk factors for ethnic disparities in asthma that are not mediated by SES.

Recent findings

Exposures and factors correlated with ethnicity through SES (e.g. indoor and outdoor air quality, smoke exposure, and access to healthcare) are likely to explain a significant proportion of the observed ethnic differences in asthma morbidity. However, other factors correlated with ethnicity (e.g., genetic variation) can impact ethnic disparities in asthma independently of and/or interacting with SES-related factors.

Summary

SES is a rough marker of a variety of environmental/behavioral exposures and a very important determinant of differences in asthma prevalence and severity among ethnic minorities in the U.S. However, SES is unlikely to be the sole explanation for ethnic disparities in asthma, which may also be due to differences in genetic variation and gene-by-environment interactions among ethnic groups.

Keywords: Childhood asthma, asthma epidemiology, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, race, minorities

Introduction

Asthma, a global public health problem [1], affects over 6.8 million children and adolescents in the U.S.[2]. There is profound variability in the prevalence and morbidity of asthma among ethnic groups [3].

Ethnicity is strongly correlated with socioeconomic status (SES) in the U.S., where members of certain ethnic groups (e.g., African Americans, Puerto Ricans) are disproportionately represented among the poor. Because poverty has been associated with increased asthma morbidity, it has been postulated that SES is solely responsible for ethnic differences in asthma and asthma morbidity. The effect of SES on illnesses such as asthma is likely mediated through pathways including environmental exposures, access to health care, stress, and psychological/cultural factors [4]. However, ethnicity is also correlated with racial ancestry, which may influence asthma disparities through differences in the frequency of disease-susceptibility alleles.

The purpose of this article is to review current evidence to support the role of SES and other factors as potential explanations for ethnic-related differences in asthma, and to suggest potential future directions for research in this field.

Asthma and Asthma Morbidity in Ethnic Minorities

The prevalence, morbidity, and severity of asthma are higher in children who belong to certain ethnic minorities [5, 6], and/or whose households report indicators consistent with low SES [7**, 8]. Although the overall prevalence of current childhood asthma in the U.S. is 8.7%, it varies widely by ethnicity, ranging from 4–5% in Asian Indians and Chinese to 19% for Puerto Ricans, with non-Hispanic whites and other minorities ranking in the middle [2, 3, 9*, 10*] (Table 1). Similarly, the rate of current asthma in children from families below the federal poverty threshold is higher (11.1%) than in families above it (7.7–8.5%)(10). Asthma severity is higher in certain ethnic groups such as Puerto Ricans and African Americans [11]. African Americans have more ER visits, hospitalizations, and higher mortality rates from asthma than whites [3]. In contrast to the low mortality rates from asthma among Mexican-Americans (0.3 per 100,000), mortality among Hispanics in New York City, which has a large proportion of Puerto Ricans, is approximately 1.3 per 100,000 [12**].

Table 1.

Asthma: current prevalence and mortality rates among children 0–17 years of age in the United States

We will review the main mechanisms and potential factors underlying the association between socioeconomic status, ethnicity and asthma.

Environmental exposures

Many environmental factors influence the pathogenesis and severity of asthma:

Indoor allergens

Compared to rural areas and suburbs, indoor allergen levels are higher in urban households in low-income areas and in those hosting multiple families [13*, 14]. Inner-city households have higher levels of indoor allergens such as cockroach, which are associated with increased asthma morbidity. Differences in allergic sensitization among ethnic groups are more pronounced in inner-city environments. Using data from inner-city children in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), Stevenson et al. found that Mexican Americans were three times more likely and that African Americans were four times more likely to be sensitized to cockroach than whites (after adjustment for age, gender, and indicators of SES factors)[14]. Children with asthma who live in the inner city also tend to have more ER visits for asthma than their counterparts from rural regions [15].

Residence in inner-city areas partly explains the high levels of exposure of certain ethnic minorities to high levels of indoor allergens [5]. Two studies of asthmatic children in the U.S. Northeast showed that Hispanic and African-American ethnicity are associated with reduced exposure to high levels of dust mite allergen but increased exposure to cockroach allergen, even after accounting for indicators of SES [16, 17]. Potential explanations for the observed association between ethnicity and indoor allergen exposure include residual confounding by housing characteristics and/or behavioral differences among ethnic groups. Although a nationwide survey showed no association between ethnicity and dust mite allergen levels in the beds of U.S. homes, it was limited by small sample size and thus had inadequate statistical power [18].

Ethnicity has been associated with patterns of allergic sensitization (atopy) in children with and without asthma. African-American and Puerto Rican children (with and without asthma) are more likely to be sensitized to cockroach and dust mite than white children [14]. Since African Americans have been shown to be exposed to relatively low levels of dust mite allergen, this finding suggests ethnic differences in susceptibility to sensitization to specific allergens.

Although most children with asthma are atopic, a significant proportion of atopic children do not have asthma. This dissociation between atopy and asthma varies by ethnicity. For example, Mexican Americans have a similar prevalence of atopy but a lower prevalence of asthma than Puerto Ricans. Determinants of ethnic differences in susceptibility to asthma in atopic children have been largely unexplored.

Cigarette Smoking

Approximately 20% of U.S. adults smoke [19] with significant variation by SES: smoking prevalence is ~46% in people with a General Education Development (GED) diploma, 22% for those with a college education, and ~7% for persons with a graduate degree. Smoking is also more prevalent among subjects living below the federal poverty level (31%). Smoking rates vary widely among ethnic groups, with American Indians and Alaska Natives having the highest rates at ~32%, and Asians the lowest at 10%. Despite marked differences in asthma prevalence and morbidity, African Americans and whites have the same rates of cigarette smoking (approximately 22–23%). Among 12- to 17-year-olds participating in a survey from 1999 to 2001, reported smoking rates were 28% for American Indians / Alaska Natives, 16% for whites, 11% for Hispanics, and 7% for non-Hispanic blacks [20].

Pre- and post-natal exposures to cigarette smoking are associated with asthma and asthma morbidity in childhood [21*]. In utero smoke exposure varies widely among ethnic minorities: 20% in American Indians, 16% in whites, 10% in Puerto Ricans and non-Hispanic blacks, 5% in Japanese, 3% Mexicans, and 1.5% in Central / South Americans [22]. In utero smoke exposure also varies by insurance type and education status [23].

During childhood, the prevalence of tobacco smoke exposure and levels of salivary cotinine are higher in children with asthma symptoms and doctor-diagnosed asthma, with a more pronounced difference in children from lower SES [24*]. Smoke exposure increases asthma morbidity; conversely, smoke-free laws have been associated with fewer asthma ER visits both in children and in adults [25*].

Smoking behavior among adults varies with ethnicity and SES, with members of certain ethnic groups (e.g., Puerto Ricans) smoking more often and/or more heavily than members of other groups (e.g, Mexicans). Thus, differences in parental smoking could account for part of the observed ethnic disparities in childhood asthma. However, few studies have tried to assess the effects of smoking on ethnic differences in asthma. In a study of over nine thousand people, Beckett et al. found that an association between Hispanic origin (mainly Puerto Rican) and increased risk of asthma was not influenced by passive exposure to smoking at home [26].

Air pollution

Outdoor pollutants can trigger asthma exacerbations and may play a role in asthma pathogenesis. Non-whites are more likely to live in areas with elevated levels of air pollutants, including particulates, carbon monoxide, ozone and sulfur dioxide [27, 28**]. A study in New York City showed higher rates of asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations in children from highly polluted areas such as the Bronx, which also has a high percentage of residents from minority populations [29].

Nitrogen oxide and diesel exhaust particles (DEP), markers of traffic-related air pollution, have also been associated with increased asthma symptoms [30**]. Recent data suggest that the effect of DEP may be modified by genetic polymorphisms: in a cohort of children in Cincinnati, high DEP exposure was associated with increased risk of wheezing only in carriers of allele Val(105) in the gene for glutathione s-transferase π (GSTP1)[31].

Access to healthcare

Access to healthcare is determined by several factors, which in turn influence asthma morbidity.

Household income and insurance status

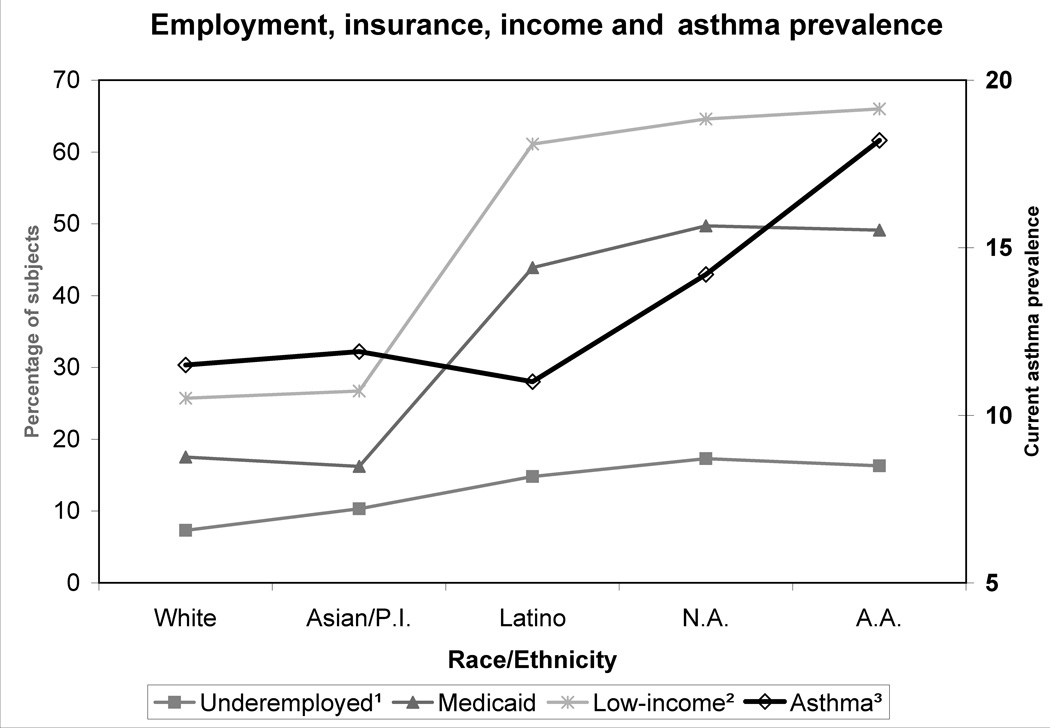

In a study of over 100,000 children (the National Survey of Children’s Health), Flores et al. found marked differences between ethnic groups with regard to full-time employment rates, household income, and insurance coverage and type [32**]. In that study, the prevalence of asthma was higher in ethnic groups with relatively low employment rates, income, and insurance coverage (Figure 1). In New York City, asthma “hotspots” correspond to areas with higher concentrations of ethnic minorities, low-income households, and public housing [33].

Figure 1. Underemployment, household income, insurance type, and asthma prevalence in children 0–17 years of age in the United States.

Data from: Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC, Pediatrics 2008;121:e286-98[32]

1Percentage of households without a full-time employed adult. 2Percentage of households with combined income below 200% of the federal poverty level. 3Reported asthma prevalence. PI = Pacific Islander. NA = Native American. AA = African American.

Lack of adequate health insurance has a negative impact on asthma management by imposing barriers to appropriate diagnosis and treatment [28]. Recent advances in both long-term and acute asthma management may exacerbate such inequality, as they would only be accessible to those with adequate insurance. It should be noted, however, that lack of access to healthcare is unlikely to be the sole explanation for ethnic differences in asthma outcomes. For example, Puerto Ricans (who are U.S. citizens) have greater morbidity from asthma than Mexican immigrants in spite of easier access to healthcare.

Stress and comorbidities

Exposure to stress/violence and co-existing illnesses such as obesity and depression may partly explain the ethnic differences in asthma that are mediated by SES.

Exposure to stress and violence

Long-term maternal stress in early life has been associated with increased risk of childhood asthma, independently of other factors such as low SES [34*]. Cohen et al. recently reported that physical or sexual abuse was associated with current asthma morbidity in a cross-sectional study of Puerto Rican children [35**]. Family structure also plays a role, with children living with a single mother at higher risk for inadequate management of and increased morbidity from asthma [36*]. Together with results from other recent studies [37*,38*,39], these findings suggest that exposure to stress and violence (which is more common in ethnic minorities) influences the pathogenesis and morbidity of asthma in childhood.

Obesity

Obesity has been associated with asthma in different populations [40, 41*]. Among asthmatics in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP), the proportion of overweight was higher in blacks and Hispanics than in whites and in members of other races [42*].

The influence of obesity on asthma could be due to several factors, many of which are associated with SES (e.g., diet and exercise). However, it has been reported that increased adiposity in infancy is associated with recurrent wheeze later in childhood [43*]. This points towards other mechanisms, such as genetic factors and a general inflammatory state [44**], which could predispose to airway inflammation. Severe obesity further impairs airflow due to increased chest wall resistance. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and habitual snoring not only have obstructive problems but also tend to have increased airway inflammation at baseline [45]. Several adipokines (cytokines produced by adipose tissue) have been implicated in airway inflammation [46*].

Depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety are more prevalent in youth of lower SES [47] and/or with limited education (48). Adolescents with asthma have nearly twice the risk of depressive or anxiety disorders as adolescents without asthma [49*]. In a large population-based birth cohort in Finland, depressive symptoms and emotional behavioral problems before 8 years of age were associated with asthma in early adulthood [50]. Whether preceding or accompanying asthma, there is a clear relationship between depression and increased symptom report, poor medication adherence, and increased school absenteeism [51*]. Finally, co-morbid depression/anxiety are under recognized and undertreated in youth with asthma [52].

Psychological and cultural factors

Parental psychological and cultural factors may affect childhood asthma in several ways. Parents of black and Hispanic children worry more about their child’s asthma but have lower expectations for symptom control and functionality, more competing priorities, and more concerns about over-medication and medication dependency than white parents [53**]. They also tend to have worse compliance with preventive medications, even when insurance coverage is not an issue [54]. Similar results have been elicited in individuals of South Asian descent and in other minorities in the United Kingdom [55*]. Among adolescent asthmatics in the U.S., minority and low SES subjects were more likely to have an inaccurate perception of their asthma control, with an evident tendency toward under-perception of symptoms [56].

Physician’s attitudes and perceptions also play a role. Among a large sample of adult asthmatics, African Americans were more likely to have their asthma severity underestimated by treating physicians, resulting in less inhaled steroids usage, and less instruction on exacerbation management [57*]. Similar findings have been reported with minorities in the Netherlands [58], where universal healthcare is available.

Beyond socioeconomic status

We have reviewed several mechanisms by which SES may influence asthma, particularly in ethnic minorities. However, factors correlated with SES are unlikely to explain all the variability in asthma prevalence, severity and mortality among ethnic groups [59].

Non-Hispanic blacks have a higher prevalence of current asthma, exacerbations, and hospitalization rates than whites even after adjusting for several demographic and socioeconomic factors [5].

Puerto Rican children have higher and Asian children lower asthma prevalence and hospitalization rates than whites, even after adjusting for sociodemographic variables [60].

Mexican Americans have lower asthma prevalence than most other groups, yet tend to have incomes and insurance coverage similar to that of African Americans and Native Americans; they are also more likely than whites, and almost as likely as African Americans, to be sensitized to indoor aeroallergens [14].

All of the above findings could be explained by residual (unmeasured) confounding by factors related to SES (e.g., housing characteristics, exposure to stress and violence). However, in a survey of over 3,000 individuals in almost 1,000 homes in the same area in Brooklyn (NY), Ledogar et al. [59] found that ethnic differences in asthma prevalence (5% in Dominicans vs. 13% in Puerto Ricans) were not influenced by residence (cluster or building), education level, country of education, or household size. This is a thought-provoking study, as differences in asthma prevalence were present in ethnic groups sharing very similar environments and SES within a same geographic area.

A potential explanation for part of the observed ethnic disparities in asthma is genetic predisposition. The heritability of asthma has been reported to be between 36 and 79%, and several groups have identified genomic regions and/or genes potentially implicated in the pathogenesis and/or severity of asthma [61**]. Although some of these studies have included members of ethnic minorities (e.g., African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians) most have been conducted in non-Hispanic whites. As an example, results for studies of three candidate genes for asthma are listed in Table 2. While there are potential asthma-susceptibility genes, none has been consistently replicated across all major ethnic groups. Ongoing genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified and will continue to identify asthma-susceptibility genes. Ethnic differences in the effect of a disease-susceptibility gene were recently reported in a GWAS of diabetes mellitus type II [72*]: of relevance, the observed differences were likely due to variation in allelic frequencies by ethnicity, as well as potential interactions between genetic variants and unmeasured environmental factors. Thus, recent findings suggest that well-conducted GWAS of asthma in ethnic minorities (including examination of gene-by-gene and gene-by-environment interactions) should provide valuable insights into the causes of ethnic disparities in asthma.

Table 2.

Selected candidate-gene association studies of asthma in different ethnic groups

| Gene | Ethnic group | Results and comments |

|---|---|---|

| ADAM33 | African-Americans | One study found three SNPs weakly associated with asthma or allergic sensitization [62]; another found no association [63]. |

| Hispanics | One study found two SNPs associated with asthma and allergic sensitization in Hispanics [62]; others found no association in Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Costa Ricans [63–65]. | |

| Asians | One study found three SNPs associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis in Chinese [66]; another found no association in Koreans [67]. | |

| ADRB2 | African-Americans | One study found no association of the Arg16Gly polymorphism with bronchodilator responsiveness [68]. |

| Hispanics | One study found an association with bronchodilator responsiveness in Puerto Ricans but not in Mexicans [69]. | |

| IL13 | Hispanics | One study found an association with response to inhaled steroids and allergy-related phenotypes in Costa Ricans [70]. |

| Asians | One study found an association with response to leukotriene inhibitors in Koreans [71]. |

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Conclusions and future directions

Differences in SES among ethnic groups are likely to influence ethnic disparities in asthma morbidity through several mechanisms. An improved understanding of these SES-related pathways is essential and could lead to a reduction in current asthma disparities. However, the interactions between these factors are very complex and difficult to dissect and thus comprehensive policies that address SES disparities as a whole should help reduce the asthma burden in ethnic minorities.

Although vigorous efforts to address SES-related risk factors for asthma are essential and should continue, we must also recognize the importance of understanding the impact of genetic variation and its interaction with environmental exposures on asthma pathogenesis in ethnic minorities.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported by grants HL04370, HL066289, HL079966, HL073373 and T32 HL07427 from the National Institutes of Health.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006 Aug 26;368(9537):733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trends in Asthma Morbidity and Mortality. New York: American Lung Association; 2007. [updated 2007; cited 2008 October]; Available from: http://www.lungusa.org. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ. The State of Childhood Asthma, United States, 19807#x02013;2005. Hyatsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright RJ, Mitchell H, Visness CM, et al. Community Violence and Asthma Morbidity: The Inner-City Asthma Study. Am J Public Health. 2004 Apr 1;94(4):625–632. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaniel M, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Racial Disparities in Childhood Asthma in the United States: Evidence From the National Health Interview Survey, 1997 to 2003. Pediatrics. 2006 May 1;117(5):e868–e877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai Y, Hillemeier M, Lengerich E. Racial/ethnic disparities in symptom severity among children hospitalized with asthma. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(1):54–61. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cope SF, Ungar WJ, Glazier RH. Socioeconomic factors and asthma control in children. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2008;43(8):745–752. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20847. This interesting study shows SES influences asthma control status, in a setting with universal healthcare coverage, even after adjusting for healthcare utilization and controller medication usage.

- 8.CDC. QuickStats: Percentage of children aged <18 years who currently have asthma by race/ethnicity and poverty status, National Health Interview Survey - United States, 2003–2005. MMWR. 2007 Feb 9;56(05):99. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brim SN, Rudd RA, Funk RH, Callahan DB. Asthma Prevalence Among US Children in Underrepresented Minority Populations: American Indian/Alaska Native, Chinese, Filipino, and Asian Indian. Pediatrics. 2008 Jul 1;122(1):e217–e222. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3825. This paper looks at differences in asthma prevalence in severkal ethnic minorities in the U.S. by race, region, place of birth, income and insurance coverage.

- 10. Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, et al. National Surveillance for Asthma -United States, 1980–2004. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2007;56(8):18–54. This is a comprehensive report on the epidemiology of asthma in the U.S. over the last 25 years, both in children and adults.

- 11.Ramsey CD, Celedon JC, Sredl DL, et al. Predictors of disease severity in children with asthma in Hartford, Connecticut. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39(3):268–275. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen RT, Celedón JC. Asthma in Hispanics in the United States. Clinics in Chest Medicine. 2006;27(3):401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.004. Very comprehensive review on the status of asthma in Hispanics in the United States, including prevalence, morbidity, risk factors, and management.

- 13. Salo PM, Arbes SJ, Crockett PW, et al. Exposure to multiple indoor allergens in US homes and its relationship to asthma. J All Clin Immun. 2008;121(3):678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1164. This study looks at the role of indoor allergens on asthma exacerbations, as well as risk factors for increased allergen exposure.

- 14.Stevenson L, Gergen P, Hoover DR, et al. Sociodemographic correlates of indoor allergen sensitivity among United States children. J All Clin Immun. 2001;108(5):747–752. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simons E, Curtin-Brosnan J, Buckley T, et al. Indoor Environmental Differences between Inner City and Suburban Homes of Children with Asthma. J Urban Health. 2007;84(4):577–590. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9205-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leaderer BP, Belanger K, Triche E, et al. Dust mite, cockroach, cat, and dog allergen concentrations in homes of asthmatic children in the northeastern United States: impact of socioeconomic factors and population density. Environ Health Perspect. 2002 Apr;110(4):419–425. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitch BT, Chew G, Burge HA, et al. Socioeconomic predictors of high allergen levels in homes in the greater Boston area. Environ Health Perspect. 2000 Apr;108(4):301–307. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbes SJ, Jr, Cohn RD, Yin M, et al. House dust mite allergen in US beds: results from the First National Survey of Lead and Allergens in Housing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 Feb;111(2):408–414. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC. Cigarette smoking among adults, United States 2006. MMWR. 2007;56(44):1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC. Prevalence of Cigarette Use Among 14 Racial/Ethnic Populations, United States 1999--2001. MMWR. 2004;53(3):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goodwin RD, Cowles RA. Household smoking and childhood asthma in the United States: a state-level analysis. J Asthma. 2008;45(7):607–610. doi: 10.1080/02770900802126982. The authors find an association between household smoking and an increased risk of childhood asthma at the state level in the United States.

- 22.Mathews TJ. Smoking during pregnancy in the 1990s. Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC. Preventing Smoking and Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Before, During, and After Pregnancy. Atlanta, GA: 2007. [updated 2007 July 2007; cited 2008 December 1, 2008]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/factsheets/Prevention/smoking.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delpisheh A, Kelly Y, Shaheen R, Brabin BJ. Salivary Cotinine, Doctor-diagnosed Asthma and Respiratory Symptoms in Primary Schoolchildren. Matern Child Health J. 2008;2008(12):188–193. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0229-9. This interesting paper that found that salivary cotinine levels are higher in asthmatic children and in lower SES households.

- 25. Rayens MK, Burkhart PV, Zhang M, et al. Reduction in asthma-related emergency department visits after implementation of a smoke-free law. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;122(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.029. 537-41.e3. In this very interesting study, authors found a significant reduction in the age-adjusted rate of ED visits for asthma after implementation of a smoke-free law.

- 26.Beckett WS, Belanger K, Gent JF, et al. Asthma among Puerto Rican Hispanics: a multi-ethnic comparison study of risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(4 Pt 1):894–899. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connor GT, Neas L, Vaughn B, et al. Acute respiratory health effects of air pollution on children with asthma in US inner cities. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.020. 1133-9.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shanawani H. Health Disparities and Differences in Asthma: Concepts and Controversies. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27(1):17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2005.11.002. Very interesting review on health disparities using asthma as a model, looking at biological and socioeconomic factors.

- 29.Maantay J. Asthma and air pollution in the Bronx: Methodological and data considerations in using GIS for environmental justice and health research. Health & Place. 2007;13(1):32–56. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jerrett M, Shankardass K, Berhane K, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and asthma onset in children: a prospective cohort study with individual exposure measurement. Environ Health Perspect. 2008 Oct;116(10):1433–1438. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10968. In this interesting study, authors find that increased levels of traffic pollution are associated with a significantly higher risk of incident asthma.

- 31.Schroer KT, Myers JM, Ryan PH, et al. Associations between Multiple Environmental Exposures and Glutathione S-transferase P1 on Persistent Wheezing in a Birth Cohort. J Pediatr. 2008 Oct 23; doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Medical and Dental Health, Access to Care, and Use of Services in US Children. Pediatrics. 2008 Feb 1;121(2):e286–e298. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1243. This is a very comprehensive study looking at several measures of health and healthcare use -including asthma- among ethnic minorities, and their association with socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors.

- 33.Corburn J, Osleeb J, Porter M. Urban asthma and the neighbourhood environment in New York City. Health & Place. 2006;12(2):167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kozyrskyj AL, Mai X-M, McGrath P, et al. Continued Exposure to Maternal Distress in Early Life Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Childhood Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Jan 15;177(2):142–147. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-381OC. This is an interesting paper, where authors find that long-term maternal stress during childhood is associated with asthma in their children by 7 years of age.

- 35. Cohen RT, Canino GJ, Bird HR, Celedon JC. Violence, Abuse, and Asthma in Puerto Rican Children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Sep 1;178(5):453–459. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1629OC. In this attention-grabbing study, childhood physical or sexual abuse is associated with increased asthma prevalence, health care use, and medication use.

- 36. Chen AY, Escarce JJ. Family structure and the treatment of childhood asthma. Med Care. 2008 Feb;46(2):174–184. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318156ff20. This paper looks at the relationship between living in single-parent homes or homes with several children and measures of asthma control such as office visits and medication refills.

- 37. Turyk ME, Hernandez E, Wright RJ, et al. Stressful life events and asthma in adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008 May;19(3):255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00603.x. Authors found an association between stressful events and increased asthma morbidity in adolescents, after adjusting for several sociodemographic factors.

- 38. Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Subramanyam MA, Wright RJ. Domestic violence is associated with adult and childhood asthma prevalence in India. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Jun 1;36(3):569–579. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym007. This paper shows increased childhood and adult asthma in subjects exposed to or experiencing domestic violence in India.

- 39.Jeffrey J, Sternfeld I, Tager I. The association between childhood asthma and community violence, Los Angeles County, 2000. Public Health Rep. 2006 Nov-Dec;121(6):720–728. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sithole F, Douwes J, Burstyn I, Veugelers P. Body mass index and childhood asthma: a linear association? J Asthma. 2008;45(6):473–477. doi: 10.1080/02770900802069117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jacobson JS, Mellins RB, Garfinkel R, et al. Asthma, body mass, gender, and Hispanic national origin among 517 preschool children in New York City. Allergy. 2008;63(1):87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01529.x. This study suggests there is an association between race, body mass index, gender, and asthma status in young children.

- 42.Bender BG, Fuhlbrigge A, Walders N, Zhang L. Overweight, Race, and Psychological Distress in Children in the Childhood Asthma Management Program. Pediatrics. 2007 Oct 1;120(4):805–813. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0500. In this paper, there was an increased prevalence of overweight risk among a cohort of asthmatics, when compared to the general population.

- 43. Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman S, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Higher adiposity in infancy associated with recurrent wheeze in a prospective cohort of children. J All Clin Immun. 2008;121(5):1161–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.021. In this study the authors found that increased adiposity at 6 months of age is associated with increased risk of recurrent wheezing at 3 years of age.

- 44. Litonjua AA, Gold DR. Asthma and obesity: Common early-life influences in the inception of disease. J All Clin Immun. 2008;121(5):1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.005. This is a detailed review on early factors that can influence the comorbidity between asthma and obesity, such as genetics, prenatal exposures, maternal diet, sedentary behaviors, etc.

- 45.Verhulst SL, Aerts L, Jacobs S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, obesity and airway inflammation in children and adolescents. Chest. 2008 Aug 8; doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0535. 2008:chest.08-0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim KW, Shin YH, Lee KE, et al. Relationship between adipokines and manifestations of childhood asthma. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2008;19(6):535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00690.x. Interesting study looking at different cytokines secreted by adipose tissue and their possible relationships with asthma.

- 47.Lemstra M, Neudorf C, D'Arcy C, et al. A systematic review of depressed mood and anxiety by SES in youth aged 10–15 years. Can J Public Health. 2008 Mar-Apr;99(2):125–129. doi: 10.1007/BF03405459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bjelland I, Krokstad S, Mykletun A, et al. The HUNT study. Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? Soc Sci Med. 2008 Mar;66(6):1334–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Katon W, Lozano P, Russo J, et al. The Prevalence of DSM-IV Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Youth with Asthma Compared with Controls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41(5):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.023. In this paper, the authors find that youth with asthma have a significantly higher comorbidity with depression and anxiety than healthy controls.

- 50.Goodwin RD, Sourander A, Duarte CS, Niemela S Evidence from a community-based prospective study. Do mental health problems in childhood predict chronic physical conditions among males in early adulthood? Psychol Med. 2008 May;28:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bender B, Zhang L. Negative affect, medication adherence, and asthma control in children. J All Clin Immun. 2008;122(3):490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.041. In this longitudinal study, self-reported negative affect in asthmatic children was associated with decreased asthma control.

- 52.Katon WJ, Richardson L, Russo J, et al. Quality of mental health care for youth with asthma and comorbid anxiety and depression. Med Care. 2006 Dec;44(12):1064–1072. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000237421.17555.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu AC, Smith L, Bokhour B, et al. Racial/Ethnic Variation in Parent Perceptions of Asthma. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8(2):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.007. One of the very few papers that addresses the issue of parental perception of pediatric asthma symptoms and morbidity, as well as expectations of health in their children.

- 54.Lieu TA, Lozano P, Finkelstein JA, et al. Racial/ethnic variation in asthma status and management practices among children in managed medicaid. Pediatrics. 2002 May;109(5):857–865. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smeeton NC, Rona RJ, Gregory J, et al. Parental attitudes towards the management of asthma in ethnic minorities. Arch Dis Child. 2007 Dec 1;92(12):1082–1087. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.112037. Interesting paper where authors report cultural differences in the understanding of asthma and asthma medications among minorities in the U.K.

- 56.Rhee H, Belyea MJ, Elward KS. Patterns of asthma control perception in adolescents: associations with psychosocial functioning. J Asthma. 2008 Sep;45(7):600–606. doi: 10.1080/02770900802126974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Okelo SO, Wu AW, Merriman B, et al. Are physician estimates of asthma severity less accurate in black than in white patients? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):976–981. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0209-1. In this though-provoking study, the authors find that physicians are more likely to underestimate asthma symptoms in black patients when compared to whites.

- 58.Urbanus-van Laar JJN, de Koning J, Klazinga N, Stronks K. Suboptimal asthma care for immigrant children: results of an audit study. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ledogar RJ, Penchaszadeh A, Garden CC, Iglesias G. Asthma and Latino cultures: different prevalence reported among groups sharing the same environment. Am J Public Health. 2000 Jun 1;90(6):929–935. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Claudio L, Stingone JA, Godbold J. Prevalence of Childhood Asthma in Urban Communities: The Impact of Ethnicity and Income. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16(5):332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Scirica CV, Celedon JC. Genetics of Asthma: Potential Implications for Reducing Asthma Disparities. Chest. 2007 Nov 1;132(5_suppl):770S–781S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1905. Very thorough review looking at the results and limitations of various genetic studies in different ethnic minorities, including candidate genes, linkage and association studies.

- 62.Howard TD, Postma DS, Jongepier H, et al. Association of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 33 (ADAM33) gene with asthma in ethnically diverse populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 Oct;112(4):717–722. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01939-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raby BA, Silverman EK, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. ADAM33 polymorphisms and phenotype associations in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(6):1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lind DL, Choudhry S, Ung N, et al. ADAM33 is not associated with asthma in Puerto Rican or Mexican populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Dec 1;168(11):1312–1316. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hersh CP, Raby BA, Soto-Quiros ME, et al. Comprehensive Testing of Positionally Cloned Asthma Genes in Two Populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Nov 1;176(9):849–857. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-592OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Su D, Zhang X, Sui H, et al. Association of ADAM33 gene polymorphisms with adult allergic asthma and rhinitis in a Chinese Han population. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee JH, Park HS, Park SW, et al. ADAM33 polymorphism: association with bronchial hyper-responsiveness in Korean asthmatics. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004 Jun;34(6):860–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsai HJ, Shaikh N, Kho JY, et al. Beta 2-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms: pharmacogenetic response to bronchodilator among African American asthmatics. Hum Genet. 2006 Jun;119(5):547–557. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choudhry S, Ung N, Avila PC, et al. Pharmacogenetic differences in response to albuterol between Puerto Ricans and Mexicans with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Mar 15;171(6):563–570. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1286OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hunninghake GM, Soto-Quirós ME, Avila L, et al. Polymorphisms in IL13, total IgE, eosinophilia, and asthma exacerbations in childhood. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2007;120(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang MJ, Lee SY, Kim HB, et al. Association of IL-13 polymorphisms with leukotriene receptor antagonist drug responsiveness in Korean children with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008 Jul;18(7):551–558. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282fe94c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yasuda K, Miyake K, Horikawa Y, et al. Variants in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2008 Aug;:17. doi: 10.1038/ng.207. Although not related to asthma, this study exemplifies why it is important that genetic studies be done in different ethnic populations, given that genotypic associations may vary substantially from one group to another.