Abstract

Recently, we showed a natural reprogramming process during infection with Mycobacterium leprae (ML), the causative organism of human leprosy. ML hijacks the notable plasticity of adult Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), bacteria's preferred nonimmune niche, to reprogram infected cells to progenitor/stem cell–like cells (pSLCs). Whereas ML appear to use this reprogramming process as a sophisticated bacterial strategy to spread infection to other tissues, understanding the mechanisms may shed new insights into the basic biology of cellular reprogramming and the development of new approaches for generating pSLC for therapeutic purposes as well as targeting bacterial infectious diseases at an early stage. Toward these goals, we extended our studies to identify other players that might be involved in this complex host cell reprogramming. Here we show that ML activates numerous immune-related genes mainly involved in innate immune responses and inflammation during early infection before downregulating Schwann cell lineage genes and reactivating developmental transcription factors. We validated these findings by demonstrating the ability of infected cells to secrete soluble immune factor proteins at early time points and their continued release during the course of reprogramming. By using time-lapse microscopy and a migration assay with reprogrammed Schwann cells (pSLCs) cultured with macrophages, we show that reprogrammed cells possess the ability to attract macrophages, providing evidence for a functional role of immune gene products during reprogramming. These findings suggest a potential role of innate immune response and the related signaling pathways in cellular reprogramming and the initiation of neuropathogenesis during ML infection.

Introduction

The glial cells of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Schwann cells, possess the unique capacity to synthesize the myelin sheath around axons and provide trophic factors for neuronal survival (Pereira et al., 2012). Despite the acquisition of a sophisticated differentiation/myelination program during development, terminally differentiated adult Schwann cells show an unprecedented plasticity; they can switch off the myelin program and attain a dedifferentiated state (Chen et al., 2007; Jessen and Mirsky, 2008). This plasticity largely contributes to the remarkable regenerative capacity of peripheral nerves following injury (Fancy et al., 2011). Intriguingly, human PNS involvement during infection with Mycobacterium leprae (ML), the causative organism of human leprosy, which is a classical infectious neurodegenerative disease (Sabin et al., 1993), is directly associated with the capacity of ML to specifically target Schwann cells (Stoner, 1979). Once invaded, ML take advantage of the plasticity of adult Schwann cells to colonize and establish a bacterial niche within this privileged and protected niche, as the blood–nerve barrier limits immune cell trafficking within the PNS (Rambukkana, 2010).

In a mouse model that mimics early ML infection of adult peripheral nerves, we recently showed that Schwann cells from adult peripheral nerves undergo a reprogramming process in response to intracellular ML (iML) and convert infected Schwann cells to highly immature progenitor/stem cell–like cells (pSLCs), which are more suitable for bacterial dissemination (Masaki et al., 2013). In Schwann cells, ML turn off Schwann cell differentiation/myelination-associated genes and reactivate developmental-associated genes/transcription factors, changing cell fate to pSLCs over time. The established methods of cell reprogramming of adult somatic cells, such as fibroblasts to pluripotent stage or cell fate change from one somatic cell type to another by ectopic overexpression of a few defined transcription factors (TFs), are complex processes (Baeyens et al., 2005; Davis et al., 1987; Ieda et al., 2010; Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006; Vierbuchen et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2008). It is likely that iML-induced reprogramming of Schwann cells is even more complex due to the fact that the ML bacillus is equipped with a plethora of highly biologically active components and each and every bacterial component or their combined effects may have the capacity to activate many biological events in Schwann cells, including cells' defense reactions that may contribute to both reprogramming and to pathological events during early infection. In this regard, it is interesting that innate immune or inflammatory pathways that are triggered by viral vectors used for TF-induced conversion of embryonic fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have been linked to effective cell reprogramming (Lee et al., 2012). These findings suggest that host cells' defensive responses to viruses are likely to involve increased transcriptional competence, resulting in the expression of genes that are normally shut down in somatic cells. However, unlike viral vectors, natural infection with whole ML bacilli is likely to produce a full spectrum of highly complex cellular and defensive reactions in Schwann cells to adapt to pathogenic challenges, which in turn may be associated with increased transcriptional competence and subsequent modulation of gene expression driving a wide range of cellular activities, including cell reprogramming. However, such biological processes that precede or accompany Schwann cell reprogramming following ML infection are unknown.

Here, we show that, in addition to downregulating Schwann cell lineage transcripts and reactivating developmental genes, ML rapidly induce a large number of immune-related genes comprising mostly innate immunity and chemokine-associated genes right from the very early stage of Schwann cell infection and peaking in their expression when Schwann cells have changed their cell identity to pSLCs. We also validated some of these immune gene products—chemokines/cytokines at the protein level as secreted soluble factors during the reprogramming process. The functional evidence for the acquisition of such immune-related factors by reprogrammed Schwann cells is shown by their ability to attract macrophages, thus showing a possible role of immune responses and their associated signaling during Schwann cell reprogramming.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of primary Schwann cells from adult peripheral nerves

Schwann cells were separated from adult CD-1 male mice (4–6 weeks old, ICR strain code 022) and purified using a magnetic cell sorting system, as described earlier (Masaki et al., 2013). In brief, peripheral nerve tissues were isolated in minimal essential medium (MEM; Invitrogen), and connective tissues and dorsal root ganglia were carefully removed. The tissues were digested with 0.125% trypsin (Invitrogen)/0.05% EDTA and 0.1 mg/mL collagenase I (Worthington Biochemical) passed through a 100-μm mesh nylon filter (BD Falcon). The cells were collected and seeded on a laminin-coated T25 flask and were passaged and cultured in Schwann cell medium (Masaki et al., 2013) and subjected to purification by a magnetic cell sorting system using anti-p75 antibody (AB1554, Millipore) according to manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec). The enriched cells were further purified by FACS Vantage dual-laser flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using anti-p75 antibody, and clonal cells were prepared from p75+ cells as described (Masaki et al., 2013).

ML infection of mouse Schwann cells and reprogramming

Purified Schwann cells were grown in collagen-coated T75 flasks (BD Biosciences) and infected with ML. Reprogrammed cells were generated according to our previous protocol (Masaki et al., 2013). In vivo–grown viable ML derived from nude mouse footpads were prepared as described previously (Truman and Krahenbuhl, 2001). Briefly, p75+/Sox10+/Sox2+ Schwann cells were infected with M. leprae and maintained in standard Schwann cell medium for 4 weeks. They were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for p75− cells and their phenotypes were confirmed as p75−/Sox10−/Sox2+. Reprogrammed cells from this population were isolated on the basis of their ability to grow in mesenchymal stem cell medium (Mesencult; StemCell Inc.) and were termed as pSLCs. These pSLCs were transduced with a CopGFP-CDH-MSCV-cG reporter vector (Choi et al., 2001) obtained from System Biosciences (Mountain View, CA, USA). Stable expression of copGFP in pSLCs was performed using a lentiviral expression system according to the manufacturer's protocol and described as reported earlier (Masaki et al., 2013).

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

Immunofluorescence was performed as described (Ng et al., 2000). In brief, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature and 100% methanol (Sigma) for 10 min at −20°C. The samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times, blocked with 10% goat serum, and incubated with primary antibody for 1 h. After washing and incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (Invitrogen), images were captured with Nikon Eclipse 2100, Zeiss LSM710 confocal, and Zeiss AX10 Observer live imaging microscopies.

Gene expression analyses

Microarrays were performed using Affymetrix mouse Genechips according to the manufacturer's protocol as described previously (Masaki et al., 2013). In brief, total RNA was isolated from control uninfected Schwann cells and ML-infected Schwann cells or pSLCs using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN). Affymetrix Test3 arrays and mouse genome MG-430A2 arrays were probed with the cRNA prepared by reverse transcription of the total RNA. Expression analyses of control primary Schwann cells and infection at days 3, 7, 14, and 28, as well as reprogrammed Schwann cells/pSLCs derived from day-28 post infection were analyzed by applying the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) method (Irizarry et al., 2003). Affymetrix proprietary CEL-format files were read into the R statistical programming environment (v. 2.15.2), complemented with the Bioconductor analysis suite (v. 2.12) (Gentleman et al., 2004). To determine a starting list of immune-related probes, a search was performed, iterating through all probes detailed in the Affymetrix Mouse 430A2 microarray annotations library (version 2.8.1), searching for the immune-related gene ontology (GO) term GO:000695-immune response. Any probes included in this annotation were initially included in the analysis. Gene symbols associated with all probes were provided by this same library. For all time points, mean probe detection values of replicates were used. Individual genes were further verified as immune related on the basis of the available data from published literature. For the analysis of immune-related genes affected by infection with ML, an initial threshold of 1 log2-fold change (at any time point) from the control, uninfected time point, was used. The remaining list of probes for genes with canonical immunological function was then used for further analysis. Data shown in Fig. 1 was analyzed according to Masaki et al. (2013).

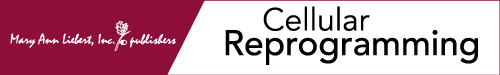

FIG. 1.

Immune-related genes dominates early M. leprae–induced reprogramming of Schwann cells. The total number of upregulated immune-related genes as compared to upregulated embryonic/developmental transcription factor genes and downregulated Schwann cell lineage marker genes differentially expressed (threshold off value >1.5) in infected Schwann cells at days 3, 7, 14, and 28 (Masaki et al., 2013). Note that the number of immune-related genes appeared very early in infection and is maintained during the reprogramming process (line across the bars). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/cell

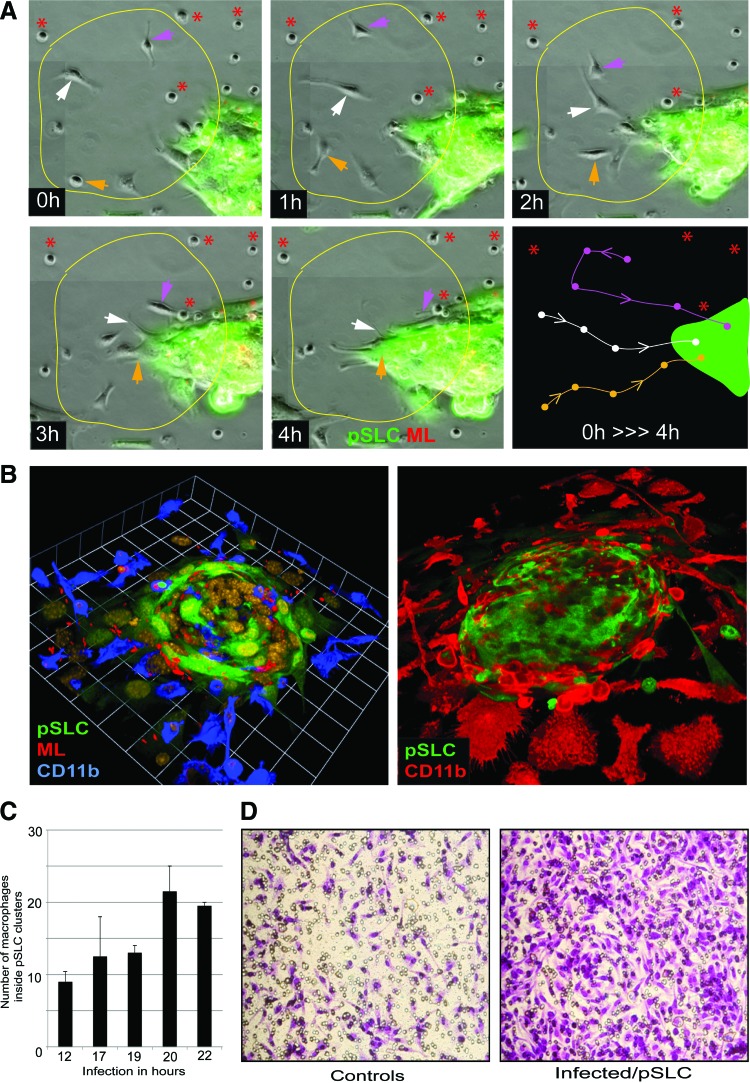

Migration assays and time-lapse and confocal microscopy of macrophage–pSLC co-culture

Isolation of macrophages from adult mouse peritoneal macrophages and co-cultures with green fluorescent protein (GFP)+pSLCs are described in our previous report (Masaki et al., 2013). Briefly, peritoneal macrophages were isolated from adult CD1 mice, centrifuged, and resuspended in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 8 mM HEPES, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and penicillin/streptomycin. Adherent macrophages were removed, washed in 10% FCS in PBS, and analyzed by FACS and immunolabeling. Preparations containing macrophages positive for F4/80 (85%) and CD68 markers (almost 100%) were used for the experiments. Migration of macrophages in response to soluble factors released by pSLCs was measured by Transwell migration assay as described (Masaki et al., 2013). Macrophage migration toward pSLC clusters was also monitored in live and fixed co-cultures using time-lapse microscopy (Zeiss Cell Observer) and confocal microscopy (LSM 710, Zeiss), respectively. For these experiments, macrophages were added to GFP+pSLCs in mesenchymal stem cell medium without supplements, and fixed cells were immunolabeled with antibodies to PGL-1 to locate ML (or in some cases labeled ML were used) and to various macrophage markers, F4/80, CD68, CD11b, and CD206. Confocal images and quantification of macrophages within pSLC clusters were analyzed using Volocity 5.5 software.

Chemokine/cytokine protein expression from infected and reprogrammed cells

Immune factors released from infected Schwann cells at different time points and reprogrammed cells/pSLCs were detected in culture supernatants using cytokine antibody arrays (Proteome Profiler-Mouse Chemokine/Cytokine Array Panel A array Kit, R & D Systems). Both experimental and quantification analyses were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Integrated density of each detected protein was calculated using ImageJ.

Results

Innate and inflammatory gene activation in early reprogramming process during ML infection

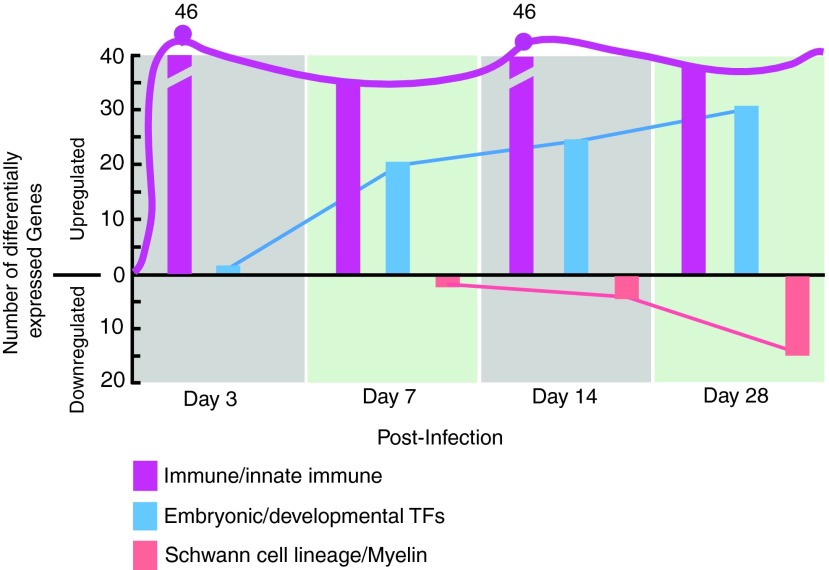

Infection of lineage-committed Schwann cells with leprosy bacteria results in reactivation of developmental/embryonic transcription factors and downregulation of Schwann cell lineage marker genes, resulting in the reprogramming of infected cells to pSLCs (Masaki et al., 2013). Although these transcriptional changes occur progressively over the course of infection, further transcriptome analysis revealed that numerous immune-related genes were differentially expressed as early as 3 days after infection, and some of these genes continued this expression during reprogramming process (Fig. 1). A heatmap of log2-fold changes relative to the uninfected control time point are presented in Figure 2A, with the genes clustered by Euclidean distance and average linkage for clarity and to facilitate highlighting of genes with similar patterns in change of expression across the time points. The majority of these selected immune gene profiles are related to the innate immune response, and others are members of the chemokine and cytokine families. Selected genes with individual expression levels from the heat map are depicted in Figure 2B. The heatmap shows the progression of the innate immunity changes across the time course. Although several immune genes were upregulated in Schwann cells as early as day 3 and day 7 in response to intracellular ML, they were quickly downregulated over time with a strong downregulation in reprogrammed cells/pSLCs. However, other immune genes were upregulated right from day 3 postinfection and maintained or increased their expression up to the reprogrammed stage (Fig. 2A), suggesting complexity and nonlinearity of this innate immune response signal upon infection on the road to reprogramming.

FIG. 2.

Differentially expressed individual immune-related genes in M. leprae–infected Schwann cells. (A) Heat map of selected immune-related genes found to be more than two-fold (1log2-fold) differentially expressed relative to uninfected control. Five time points (3, 7, 14, and 28 days and pSLC stage time point) are shown relative to control and are calculated as the mean of two microarrays per time point post-infection (control also having two biological replicates averaged). Genes are clustered by Euclidean distance for clarity (dendrogram visible on the left). (B) Selected genes (bolded genes from Fig. 2A), associated with the innate immune response, with differential expression (log2-fold change) relative to uninfected control, represented by colored bar length for different time points of infection. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/cell

Of particular interest is the modulation of genes encoding the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are receptors of the innate immune system and recognize pathogen-associated molecules. TLRs are known to sense distinct pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2010). The recognition of PAMPs by TLRs leads to the recruitment of the adaptor molecules, such as Myd88, and subsequent activation of kinase-driven signaling pathways, leading to the activation of global regulator nuclear factor-κβ (NF-κβ and thereby expression of host immune genes (Dev et al., 2011). Interestingly, TLR1 and TLR2 were upregulated in Schwann cells early in ML infection and then turned off, whereas TLR2, TLR4, and their common adaptor molecule Myd88 remained activated mostly over the course of reprogramming. Although various TLRs exhibit different patterns of expression in response to different PAMP recognition patterns, ML-induced initial and continuous upregulation of various TLRs suggests that Schwann cells, which are typically nonimmune cells, possess the capacity to elicit innate immune response to a greater extent by expressing a large number of innate immune genes in response to ML. However, the functional relevance of TLR gene modulation in relation to reprogramming or nerve pathogenesis associated with ML infection remains to be elucidated.

The signalling cascade coupled to TLR activation is also very similar to that of interleukin-1 receptors (Loiarro et al., 2010). The interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase 4 (Irak4) gene encodes a kinase that activates NF-κβ in both TLR and T lymphocyte receptor signaling pathways and is a serine/threonine-protein kinase that plays a critical role in initiating innate immune response against foreign pathogens (Loiarro et al., 2010). Interestingly, ML uprgulated the expression of Irak4 in Schwann cells from day 3 and peaked at days 14 and 28 postinfection and maintained its expression in pSLCs, albeit, at a slightly lower level (Fig. 1A, B). It is known that the IRAK4-mediated innate immune response is orchestrated by TLRs and interleukin (IL)-receptor family members, including IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) (Loiarro et al., 2010). Like Irak4, ML also continuously upregulated the IL-18 transcript, which encodes the ligand for IL-18R (Gillespie and Horwood, 1998). Because Irak4 activation is mediated by Myd88 (Loiarro et al., 2010), a common signaling adaptor protein downstream of TLRs and IL-18R, and ML activate key innate immune genes encoding Irak4, TLRs, and Myd88 as well as IL-18R ligand (Fig. 2), it is likely that intracellular ML orchestrate a complex innate immune signaling cascade that might influence other nonimmune gene transcription associated with reprogramming of Schwann cells or begin the inflammatory response that plays a key role in neurodegeneration during infection.

In addition to the essential role played by Irak4 in mediating TLR and IL-receptor signaling, recent studies have also shown that Irak4 is responsible for the production of cytokines, chemokines, and other proinflammatory mediators (Li, 2008). In this regard, there is evidence that plasmacytoid dendritic cell response in rheumatoid arthritis can be repressed by Irak4 kinase inhibition (Chiang et al., 2011), suggesting a therapeutic potential of Irak4 inhibitors for the treatment of autoimmune diseases (Cohen, 2009; Li, 2008). Interestingly, our findings showed that ML induced genes encoding a number of cytokines and chemokines, including those involved in monocytes/macrophage and neutrophil recruitment or activation. These cytokines/chemokines include Ccl2, Ccl7, Ccl9, Csf1, Mif Tnfsf11, and Cxcl1 (Fig. 2A, B). Furthermore, it is worth noting that genes associated with Th2 response (Il13ra, Il1rl1, Il18; Joshi et al., 2010; Kroeger et al., 2009) were also upregulated, suggesting the possibility that ML may induce Th2 response in the microenvironment of infected Schwann cells, which might lead to the initiation of Th2-associated inflammatory responses in the infected peripheral nerves under in vivo conditions, leading to neuropathogenesis. It is also interesting that some of the activated and downregulated genes were associated with MHC class I antigen presentation (Tpp2, Tapbp, Hfe, Tnfsf9, H2-K1, H2-D1, H2-Ab1). How these immune genes and their products relate to or promote Schwann cell reprogramming or neuropathogenesis needs further investigation.

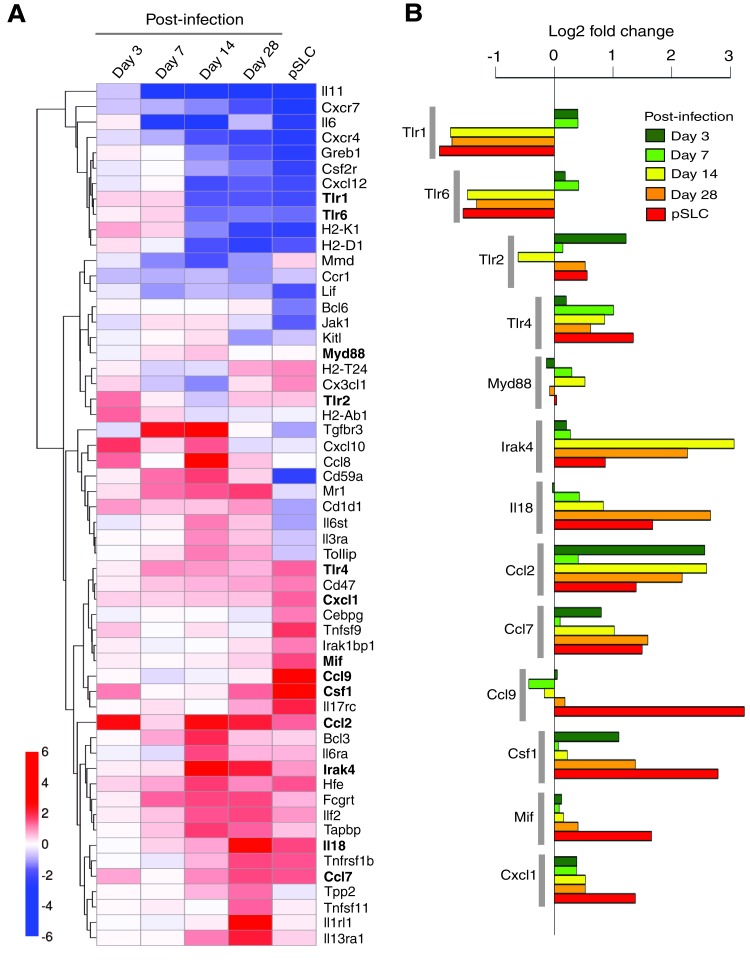

Reprogramming process accompanies secretion of immune factor proteins in infected Schwann cells

We next examined if the immune-related gene expression in infected and reprogrammed Schwann cells could be translated to immune factor proteins released by these infected cells. To test this, we collected serum/supplement-free conditioned medium (CM) from Schwann cells at different time points after infection and also from pSLCs. CM from uninfected Schwann cells was used as a control. Soluble proteins released into the medium within 24 h were analyzed and quantified using mouse protein arrays that cover a range of chemokines, cytokines, and immunomodulatory/growth factors. Figure 3 shows the quantitative analysis of mean protein expression profiles of CM from Schwann cells without and with infection at days 14 and 28 as well as reprogrammed Schwann cells/pSLCs derived from day 28 postinfection. Although infected Schwann cells at day 14 show limited release of immune factor protein at low levels, upregulation of MCP1 was significant. MCP1/CCL2 belongs to the CXC subfamily of cytokines and displays chemotactic activity for monocytes and basophils but not for neutrophils or eosinophils (Sica et al., 2000). Unlike mRNA expression of immune genes, their corresponding protein secretion to extracellular medium is a complex process; although proteins may be expressed intracellularly, they may not necessarily be secreted from the cells at a detectable level. Nevertheless, at day 28, infected cells produced a range of chemokines (MCP1/CCL2, MCP5/CCL5, CXCl1, CXCL10, CXCL11, MIG), cytokines/growth factors [IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-7, IL-2, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)] to varying degrees, and this trend progressed to reprogrammed cells, which showed the highest number of released immune factors (Fig. 3). Many chemokines and cytokines released from either infected or reprogrammed Schwann cells are of interest because they play major roles in recruitment and activation of macrophages/monocytes and other immune cells as well as initiating a cascade of immune/inflammatory reactions (White et al., 2013). Importantly, many of the released chemokines and cytokines are downstream targets of innate immune signaling exerted by TLRs and their adaptor proteins following detection of pathogens (Qian and Cao, 2013). In this regard, a recent study that shows the role of viral vector–induced innate immune signaling in reprogramming fibroblasts to iPSCs is of particular interest (Lee et al., 2012). It is possible that bacteria-induced TLR responses and subsequent production of chemokines and cytokines and their related signaling pathways could potentially influence ML-induced reprogramming of Schwann cells to pSLCs as well as initiating inflammation within the peripheral nerves during infection.

FIG. 3.

Immune factor proteins are secreted by infected and reprogrammed Schwann cells. Shown is a protein array analysis of conditioned medium from control Schwann cells, infected Schwann cells at day 14 and day 28, and reprogrammed cells/pSLCs derived from day 28-infected Schwann cells. Relative levels of secretory proteins detected by dot blot chemiluminescence were quantified by densitometry following subtraction from signals from the medium alone. Data were presented as mean values from two to three arrays. Note the progressive secretion of chemokines, cytokines, and growth factor proteins during reprogramming. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/cell

Released immune factors from reprogrammed cells influence macrophage attraction

During the reprogramming process, pSLCs derived from infected Schwann cells at day 28 postinfection released the highest number of secretory factors (Fig. 3). Because most of these immune factors are chemokines and cytokines that exert immunomodulatory functions and recruit macrophages in inflammatory processes (White et al., 2013), we used both Transwell macrophage migration assays and time-lapse microscopy with co-cultured GFP+ pSLCs with primary macrophages to evaluate their chemotactic activity in response to secreted factors from infected pSLCs. Our live cell imaging data showed that after addition of macrophages to pSLCs individual macrophages displayed a movement toward clustered GFP+ pSLCs in real time. Immunolabeling of fixed co-cultures with macrophage markers CD11b and F4/80 at different points also revealed the accumulation of numerous macrophages around pSLC clusters and macrophage migration directed toward reprogrammed cells. Double labeling with antibodies to ML (anti-PGL1 that detect ML-specific phenolic glycolipid-1) (Ng et al., 2000) and macrophage markers also revealed that migrated macrophages take up ML from infected pSLCs. Because added macrophages were not infected initially and only the GFP+ pSLCs were infected with ML, bacterial transfer to macrophages in high numbers is likely due to macrophage infiltration toward pSLC clusters. Together, these data provide evidence that released immune factors from reprogrammed cells is functional based on their ability to influence macrophage recruitment. In agreement with the chemokine/cytokine production, supernatant from pSLCs attracted a high number of macrophages when a cell migration assay was performed with a Transwell system. In this system, cell supernatant or medium alone was placed in the lower chamber and macrophages were added to upper chamber; migrated macrophages after 24 h were labeled with Crystal Violet dye staining. Figure 4 shows the markedly increased number of migrated macrophages, as demonstrated by Crystal Violet dye staining, under the influence of pSLC medium. It appears that multiple immune factors released from pSLCs are involved in this macrophage migration because a broader CC-chemokine inhibitor alone was insufficient to ablate macrophage migration in response to pSLC conditioned medium (Masaki et al., 2013).

FIG. 4.

Immune factors secreted from infected reprogrammed Schwann cells/pSLC as chemoattractants for macrophages. (A) Time-lapse live imaging microscopy showing macrophage migration toward a ML-infected GFP + pSLC aggregate over a time course of 4 h. The circled area was followed over a 4-h period (0–4 h), and movement of individual adherent macrophages within the circle was marked by three colored arrows. The dynamics of each macrophage movement were schematically presented in the bottom third panel (0 h>>>4 h). Asterisks (red) show macrophages that did not move during the time course. (B) Confocal microscopy illustrating the incorporation and migration of macrophages toward reprogrammed cells/pSLCs after macrophage addition to infected pSLC cultures were fixed at 6 h (left) and 72 h (right) and labeled with antibodies to macrophage marker CD11b. Shown are three-dimensional images of macrophage-infected GFP + pSLC co-cultures depicting macrophage migration toward and accumulation around and incorporation into pSLCs (green). (C) Quantitative analysis of migrated macrophages that have entered into GFP + pSLC clusters at different time points (shown in hours) after macrophage addition. (D) Migrated macrophages in response to reprogrammed Schwann cells/pSLC conditioned media in a Transwell assay. Crystal Violet dye staining of macrophages migrated through the membrane in the Transwell migration assay in response to conditioned media from control (left) and pSLCs. Note that in these experiments pSLCs lack ML, yet they continue to secrete immune/chemoattractant factors that influence macrophage migration. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/cell

Discussion

Reprogramming lineage-committed tissue cells back to an embryonic stem cell–like stage or to another lineage is a highly complex and long process, involving multiple phases of molecular, biochemical, epigenetic, and structural remodeling events (Buganim et al., 2013). Despite the use of only three to four well-characterized transcription factors to convert fibroblasts to pluripotent iPSCs (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006) and the massive accumulation of literature related to iPSC cell research, how exactly these defined three to four transcription factors reprogram parent cells to iPSCs still remains unknown. Therefore, it is expected that reprogramming of primary adult Schwann cells to a stem cell–like state by infection with intact leprosy bacteria, resembling ex vivo–like conditions, involves much a more complex process entailing multiple host cellular pathways and remodeling events and an array of bacterial factors with properties to elicit diverse biological responses. Regardless of the enormity of complexity, the efforts toward the identification of mechanisms involved in such a natural reprogramming process during infection should provide new molecular insights into the systems biology of reprogramming, which could potentially lead to developing strategies not only for cell-based therapies but also targeting bacterial infections at early stage. During our efforts toward these goals, we identified here that the induction of innate immune and inflammatory responses are an early phase of reprogramming of Schwann cells to pSLCs by the leprosy bacteria. We showed the expression of numerous immune-related genes mainly involving genes in the innate immune system, including TLR signaling-associated genes and their downstream targets, which initiate inflammatory responses, including numerous chemokines and cytokines. We have validated some of the chemokines/cytokines released from early infected and reprogrammed cells at protein levels and their functional role as chemotactic factors that attract primary macrophages in vitro, suggesting the potential initiation of inflammatory responses in Schwann cells during the early reprogramming process.

In natural settings, when host cells are infected with pathogens, the first defensive mechanism of cells, innate immunity, comes into action and it, in turn, generates a flexibility for host cells to express more genes and proteins to resist the infection (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2010). Schwann cell infection by ML may also follow the same natural process, with the exception that prolonged infection converts the parent Schwann cells to the pSLC stage. It is possible that the data presented in this report—the initial induction of multiple immune genes and proteins in Schwann cells during ML infection—might be linked to the subsequent reprogramming process. However, detailed analyses are necessary to understand how this multifunctional immune signaling network connects to highly complex bacteria-induced reprogramming. In this regard, it should be noted that an intriguing innate immune/inflammatory link has already been made recently during reprogramming embryonic fibroblasts to iPSCs by a relatively less complicated (as compared to entire intact bacteria) four defined factors–induced reprogramming system (Lee et al., 2012). These studies have shown that activation of TLR3 signaling by viral vectors used for ectopic expression causes fibroblasts to express more genes by loosening the chromatin, thereby facilitating reprogramming in the presence of the four defined transcription factors (Lee et al., 2012). Interestingly, Schwann cells upregulate many TLRs and their adaptor proteins and downstream targets, including chemokines/cytokines during ML infection. How these complex innate immune signaling networks might operate during ML-induced reprogramming needs careful further investigation.

It is also well established that innate immunity is an early response to injury. This also suggests that innate immunity is also very much associated with the regeneration process, which occurs at varying degrees in different adult tissues following injury. Adult peripheral nerves possess a remarkable capacity to regenerate following injury, and dedifferentiated Schwann cells generated during this injury process are largely attributed to this regenerative property (Chen et al., 2007; Fancy et al., 2011; Jessen and Mirsky 2008). Intriguingly, leprosy bacteria appear to hijack this process and generate dedifferentiated Schwann cells by causing initial demyelination to establish the infection, colonize the cells, and subsequently reprogram them to a pSLC-like stage to spread the infection (Masaki et al., 2013; Rambukkana 2010; Rambukkana et al., 2002; Tapinos et al., 2006). In peripheral nerve injury, immune-related genes are also activated in dedifferentiated adult Schwann cells, which serve as repair cells for regeneration process (Nagarajan et al., 2002; Napoli et al., 2012). These include immune factors that activate and attract macrophages and other immune cells. Our studies have revealed that there is a significant overlap between immune-related genes activated during peripheral nerve injury and those activated during ML infection, such as Ccl2, Ccl7, Kitl, and Cxcl10, suggesting that ML may hijack, at least partly, the immune-related signaling network activated after denervation for bacterial advantage. Taken together, studies presented in this report provide valuable information for laying the foundation for further studies concerning the role of the innate immune signaling network in both cellular reprogramming and pathogenesis associated with neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Truman and Ramnuj Lahiri for the provision of M. leprae, Karen Burr for technical assistance, and Paola Basilico for participation in this study. We are grateful to many colleagues at the Rockefeller University who extended their support during the initial phase of this study. We also thank members of the core facilities at the Rockefeller University and the University of Edinburgh for their assistance with microarray analysis and confocal microscopy. We also thank the American Leprosy Missions and the Order of St. Lazarus for the funding that support the provision of M. leprae. This work was supported in part by grants from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), and Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Funds.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- Baeyens L., De Breuck S., Lardon J., Mfopou J.K., Rooman I., and Bouwens L. (2005). In vitro generation of insulin-producing beta cells from adult exocrine pancreatic cells. Diabetologia 48, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buganim Y., Faddah D.A., and Jaenisch R. (2013). Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 427–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.L., Yu W.M., and Strickland S. (2007). Peripheral regeneration. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 209–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang E.Y., Yu X., and Grogan J.L. (2011). Immune complex-mediated cell activation from systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis patients elaborate different requirements for IRAK1/4 kinase activity across human cell types. J. Immunol. 186, 1279–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.K., Hoang N., Vilardi A.M., Conrad P., Emerson S.G., and Gewirtz A.M. (2001). Hybrid HIV/MSCV LTR enhances transgene expression of lentiviral vectors in human CD34(+) hematopoietic cells. Stem Cells 19, 236–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. (2009). Targeting protein kinases for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol, 21, 317–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.L., Weintraub H., and Lassar A.B. (1987). Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 51, 987–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev A., Iyer S., Razani B., and Cheng G. (2011). NF-kappaB and innate immunity. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 349, 115–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy S.P., Chan J.R., Baranzini S.E., Franklin R.J., and Rowitch D.H. (2011). Myelin regeneration: a recapitulation of development? Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 21–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R.C., Carey V.J., Bates D.M., Bolstad B., Dettling M., Dudoit S., Ellis B., Gautier L., Ge Y., Gentry J., Hornik K., Hothorn T., Huber W., Iacus S., Irizarry R., Leisch F., Li C., Maechler M., Rossini A.J., Sawitzki G., Smith C., Smyth G., Tierney L., Yang J.Y., Zhang J. (2004). Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie M.T., and Horwood N.J. (1998). Interleukin-18: Perspectives on the newest interleukin. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 9, 109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M., Fu J.D., Delgado-Olguin P., Vedantham V., Hayashi Y., Bruneau B.G., and Srivastava D. (2010). Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell 142, 375–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R.A., Hobbs B., Collin F., Beazer-Barclay Y.D., Antonellis K.J., Scherf U., and Speed T.P. (2003). Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A., and Medzhitov R. (2010). Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science 327, 291–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen K.R., and Mirsky R. (2008). Negative regulation of myelination: relevance for development, injury, and demyelinating disease. Glia 56, 1552–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A.D., Oak S.R., Hartigan A.J., Finn W.G., Kunkel S.L., Duffy K.E., Das A., and Hogaboam C.M. (2010). Interleukin-33 contributes to both M1 and M2 chemokine marker expression in human macrophages. BMC Immunol. 11, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger K.M., Sullivan B.M., and Locksley R.M. (2009). IL-18 and IL-33 elicit Th2 cytokines from basophils via a MyD88- and p38alpha-dependent pathway. J. Leukoc. Biol. 86, 769–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Sayed N., Hunter A., Au K.F., Wong W.H., Mocarski E.S., Pera R.R., Yakubov E., and Cooke J.P. (2012). Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell 151, 547–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. (2008). IRAK4 in TLR/IL-1R signaling: Possible clinical applications. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 614–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiarro M., Ruggiero V., and Sette C. (2010). Targeting TLR/IL-1R signalling in human diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 674363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T., Qu J., Cholewa-Waclaw J., Burr K., Raaum R., and Rambukkana A. (2013). Reprogramming adult Schwann cells to stem cell-like cells by leprosy bacilli promotes dissemination of infection. Cell 152, 51–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan R., Le N., Mahoney H., Araki T., and Milbrandt J. (2002). Deciphering peripheral nerve myelination by using Schwann cell expression profiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 8998–9003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli I., Noon L.A., Ribeiro S., Kerai A.P., Parrinello S., Rosenberg L.H., Collins M.J., Harrisingh M.C., White I.J., Woodhoo A., et al. (2012). A central role for the ERK-signaling pathway in controlling Schwann cell plasticity and peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo. Neuron 73, 729–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng V., Zanazzi G., Timpl R., Talts J.F., Salzer J.L., Brennan P.J., and Rambukkana A. (2000). Role of the cell wall phenolic glycolipid-1 in the peripheral nerve predilection of Mycobacterium leprae. Cell 103, 511–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira J.A., Lebrun-Julien F., and Suter U. (2012). Molecular mechanisms regulating myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Trends Neurosci 35, 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C., and Cao X. (2013). Regulation of Toll-like receptor signaling pathways in innate immune responses. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1283, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambukkana A. (2010). Usage of signaling in neurodegeneration and regeneration of peripheral nerves by leprosy bacteria. Prog. Neurobiol. 91, 102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambukkana A., Zanazzi G., Tapinos N., and Salzer J.L. (2002). Contact-dependent demyelination by Mycobacterium leprae in the absence of immune cells. Science 296, 927–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin T.D., Swift T.R., and Jacobson R.R. (1993). Leprosy. In: Peripheral Neuropathy, 3rd ed. Dyck P.J., Thomas P.K., Griffin J.W., Low P.A., and Poduslos J.F., eds. (W.B.Saunders; ), pp. 1354–1379 [Google Scholar]

- Sica A., Saccani A., Bottazzi B., Bernasconi S., Allavena P., Gaetano B., Fei F., LaRosa G., Scotton C., Balkwill F., et al. (2000). Defective expression of the monocyte chemotactic protein-1 receptor CCR2 in macrophages associated with human ovarian carcinoma. J. Immunol. 164, 733–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner G.L. (1979). Importance of the neural predilection of Mycobacterium leprae in leprosy. Lancet 2, 994–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., and Yamanaka S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapinos N., Ohnishi M., and Rambukkana A. (2006). ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinase signaling mediates early demyelination induced by leprosy bacilli. Nat. Med. 12, 961–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman R.W., and Krahenbuhl J.L. (2001). Viable M. leprae as a research reagent. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 69, 1–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierbuchen T., Ostermeier A., Pang Z.P., Kokubu Y., Sudhof T.C., and Wernig M. (2010). Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature 463, 1035–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G.E., Iqbal A.J., and Greaves D.R. (2013). CC chemokine receptors and chronic inflammation—therapeutic opportunities and pharmacological challenges. Pharmacol Rev. 65, 47–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Brown J., Kanarek A., Rajagopal J., and Melton D.A. (2008). In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature 455, 627–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]