Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer treatment guidelines state that radiotherapy (rt) can reasonably be omitted in selected women 70 years of age and older if they take adjuvant endocrine therapy (aet) for 5 years. We aimed to assess persistence and adherence to aet in women 70 years of age and older, and to examine differences between rt receivers and non-receivers.

Methods

Quebec’s medical service and pharmacy claims databases were used to identify seniors undergoing breast-conserving surgery (1998–2005) and initiating aet. Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify predictors of aet non-persistence.

Results

Of 3180 women who initiated aet (mean age: 77.5 years), 28% did not receive rt. During the subsequent 5 years, 32% of patients who initiated aet did not persist, 2% filled only a single prescription, and 22% switched medications. Compared with rt receivers, non-receivers discontinued more often (35.5% vs. 30.1%) and earlier (1.4 years vs. 1.6 years). They also became nonadherent earlier (medication possession ratio < 80% at year 3 vs. at year 5). Predictors of nonpersistence included rt omission [hazard ratio (hr): 1.26; 95% confidence interval (ci): 1.09 to 1.46]; age (hr per decade increase: 1.15; 95% ci: 1.01 to 1.31); new medications (hr per medication: 1.01; 95% ci: 1.00 to 1.02); and hospitalizations during aet, (hr per hospitalization: 1.08; 95% ci: 1.05 to 1.11). In a subanalysis of rt non-receivers, significant predictors included hospitalizations (hr: 1.07; 95% ci: 1.02 to 1.12) and medications at aet start (hr: 0.94; 95% ci: 0.91 to 0.97).

Conclusions

Suboptimal use of aet was observed in at least one third of women. In rt non-receivers, aet use was worse than it was in rt receivers. Initiation of new medications and hospitalizations increased the risk of non-persistence.

Keywords: Adjuvant endocrine therapy, persistence, adherence, radiotherapy, breast cancer, seniors

1. INTRODUCTION

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines state that, after breast-conserving surgery (bcs), women 70 years of age and older with early-stage breast cancer can forego radiotherapy (rt) if they receive adjuvant endocrine therapy (aet) for 5 years1–3. When taken for 5 or more years, aet represents a low-risk, easily administered treatment that constitutes an ideal strategy for reducing the impact of disease in women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer4. However, the effectiveness of aet depends on optimal aet use, which has at least two dimensions: persistence (continuing to take the medication for as long as prescribed) and adherence (taking the medication as prescribed)5. Deviations from optimal aet use may curb its expected preventive and curative benefits6, and prior research has shown that women at the extremes of age range—that is, those less than 40 years or more than 75 years of age—are particularly likely to be non-persistent and nonadherent7.

The decision to omit rt is often based on the assumption that patients 70 years of age and older will be taking their aet according to guidelines and accruing maximal benefit from it. However, little is known about actual aet use in this age group. Approximately 30% of incident breast cancer cases occur after the age of 70 years, and elderly women are the fastest-growing segment of the population8. Understanding the patterns and predictors of aet use in this group might allow clinicians to determine which women can and cannot safely forego rt without incurring an avoidably high risk of recurrence and decreased overall survival9.

Senior residents in Quebec are eligible for enrollment in the public prescription drug insurance plan. The provincial health insurance agency, ramq, keeps administrative databases containing records of the prescription drug and medical services use by its beneficiaries. When linked, those databases provide a unique opportunity to study patterns and to identify predictors relating to health care and medication access and use that are less likely to be confounded by socioeconomic inequities10,11. The purposes of the present study were to assess aet use (in terms of rates and predictors of persistence and adherence) over 5 years in women 70 years of age and older with early-stage breast cancer treated with bcs, and to examine differences in aet use among patients in Quebec who had and had not received rt.

2. METHODS

2.1. Setting and Data Sources

The source population consisted of senior residents living in Quebec and enrolled in the public health and prescription drug insurance plan. Data for the study were available from 1997 to 2007 and were acquired through anonymous linkage of these administrative databases:

The ramq medical services database, containing records of fee-for-service claims for physician visits12

The ramq prescription claims database12

The ramq registrant database, containing demographic information (name, sex, dates of birth and death, postal code, and material deprivation index)

The Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services discharge abstract database (med-écho)12, which captures administrative and clinical information on nearly all hospital discharges in the province

Quebec’s material deprivation index, provided to ramq by the National Institute of Public Health of Quebec13, is calculated using data from the Canadian census14. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Office at McGill University and the provincial Access to Information Office.

2.2. Design and Study Population

Our historical prospective cohort study included women 70 years of age and older who were treated with bcs between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2005, and who initiated aet within 1 year of bcs. Incident bcs procedures were identified using ramq procedure codes in med-écho (Table i) and primary diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, adapted for Quebec (icd-9-qc)15 corresponding to localized tumour topography (Table ii)16 and confirmed through Quebec’s tumour registry. Initiation of aet was ascertained using prescription claims corresponding to aet drugs (Table iii).

TABLE I.

Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec procedure codes

| Procedure | Procedure codes |

|---|---|

| Breast-conserving surgerya | 01174, 01175, 01201, 01204, 01205, 01228, 01229 |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 01228, 01231, 01232 |

| Radiotherapy treatment | 08520, 08519, 09131, 09133, 09134, 09141, 09143, 09144, 09146, 09172, 08507, 08508, 08509, 08511, 08553, 08564, 08518 |

| Simple or modified radical mastectomy | 01230, 01231, 01232 |

| Chemotherapy treatment | 0734 |

Partial excision of breast or lumpectomy.

TABLE II.

International Classification of Diseases, 9the revision, adapted for Quebec

| Condition | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Localized or regional disease | 174 | Malignant neoplasm of female breast |

TABLE III.

Drug codes

| Drug | id typea | ID numbersb |

|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant endocrine inhibitor | ||

| Tamoxifen | din | 2088428, 2237460, 2063778, 812390, 2237596, 2084430, 851965, 851973, 2237459, 2089858, 812404, 2237597, 2296748, 2048485, 2084422, 2063751, 2296721, 1926624, 1926632, 1982281, 839353, 810444, 2048477, 657360, 419052, 1982273, 810452, 638706, 1951947, 657379, 1951939, 839361 |

| Letrozole | din | 2322315, 2309114, 2347997, 2344815, 2348969, 2338459, 2231384 |

| Exemestane | din | 2242705 |

| Anastrozole | din | 2224135 |

| Anticonvulsant | ahfs | 281212XX, 281220XX, 281292XX |

| Antidepressant | ahfs | 28160416, 28160420 |

| Benzodiazepine | ahfs | 282408XX, 281208XX |

| Antipsychotic | ahfs | 2816 080 4, 28160808, 2816 0 824, 2816 0832, 28160892, 282800X X, 289200XX |

| Opioid | ahfs | 280808XX, 280812XX |

Drug identification number (din) or American Hospital Formulary Service (ahfs).

An “X” in ahfs numbers means any digit (that is, only the first 6 digits are considered).

To ensure that at least 1 year of medical service history after bcs was available for all patients, women who became ineligible for medical insurance in the year after bcs were excluded. The date of bcs was considered the index date. Women who underwent mastectomy (Table ii) within 1 year of bcs or who received chemotherapy within 4 months of bcs (Table i) were excluded from the study on the premise that they must have had more advanced breast cancer, making them ineligible for rt exclusion. It was assumed that women who initiated aet had an estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer17.

2.3. Assessment of Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics were assessed for the year before bcs and during the time on aet. Age at diagnosis was obtained from the registrant database. The comorbidity profile of each patient was assessed using the Charlson comorbidity index (cci), calculated using the enhanced icd-9 coding algorithm published by Quan et al.18 for use with administrative databases. We adjusted the algorithm by removing the icd-9 codes for the study condition (Table ii), given that all women in the cohort had breast cancer by default. The residence of each woman was classified as rural if the second digit of her postal code was 0; otherwise, it was classified as urban, in accordance with Canada Post Corporation delivery service19.

2.4. Assessment of Patterns of Health Service and Medication Use

The number and types of prescription medications dispensed to members of the cohort were assessed using the ramq prescription claims database at baseline (3 months before aet initiation) and from the date of aet initiation onward, using drug codes from the American Hospital Formulary Service20. Specifically, we characterized the cohort’s use of anticonvulsants, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and opioids (Table iii). An “aet switch” was defined as the dispensing of an aet (tamoxifen, letrozole, exemestane, or anastrozole) different from the one originally initiated during follow-up. Using med-écho, the number of hospital admissions was assessed from the date of aet initiation for as long as the patient remained on aet. Receipt of rt was ascertained from the presence of claims in the ramq medical services database for ramq procedure codes (Table i) corresponding to treatment with rt and assessed up to 1 year after diagnosis, per guideline recommendations.

2.5. Assessment of Non-persistence

We considered that patients had become non-persistent to aet (that is, they had discontinued it) if 60 days had elapsed without a refill since the prior prescription. The 60-day time period was chosen because nearly all prescriptions (94.5%) were dispensed for 30 days. In Quebec, pharmacists have an incentive to split a 90-day prescription into three 30-day supplies so that they receive three dispensing fees, for a grand total that is higher than the fee they would receive if they dispensed only once21.

2.6. Assessment of Adherence

Adherence was measured using the medication possession ratio (mpr), defined as the percentage of eligible days in the 5-year follow-up period during which a woman had a supply of aet, as ascertained by the presence of prescription claims22–25. We adjusted the mpr by accounting for overlaps (early refills) and gaps (late refills). If an overlap was noted in the supply days of two prescriptions, the days of overlap were added to the end of the second prescription. If a gap was noted between two prescriptions, those days were not included in the count of days of aet supply. We descriptively report the mean annual mpr and the proportion of patients who maintained a mpr of 80% or higher per year. Although patients are often assumed to be “adherent,” no clinically significant adherence threshold for aet has been established for breast cancer patients to date7,25–29. However, adherence of less than 80% has been shown to be associated with poorer survival9.

2.7. Follow-Up and Censoring

Women were followed for 5 years from the date of aet initiation. Censoring occurred if a woman did not experience the outcome before the end of the observation period (5 years), if she died or was lost to follow-up, or if December 31, 2007, was reached (end of available data) before the end of the 5-year follow-up period, whichever came first. Loss to follow-up most commonly resulted when patients ceased to be eligible for drug or medical insurance for various reasons (moving out of the province, for instance).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

We first examined differences in baseline characteristics between the women who had and had not received rt. Those analyses used chi-square or two-sample t-tests (for categorical and continuous variables respectively). We used Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate the crude and adjusted associations between predictors and non-persistence (time to first discontinuation) and to estimate non-persistence hazard ratios (hrs) and 95% confidence intervals (cis). Subsequently, a stepwise selection of significant variables was performed, keeping age and cci score in the model.

Women entered the cohort dynamically and contributed person–years at risk until they experienced the outcome or were censored. Collinearity between variables was assessed using a Pearson correlation matrix. No variables were excluded from the model because of correlations with other variables (Pearson coefficient of ≥0.5). Interaction terms between time to discontinuation and number of drugs at baseline, number of new drugs started, and admissions while on aet were introduced to the model one at a time, but none of those variables was found to be significant.

Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed to compare time to aet non-persistence (discontinuation) between rt receivers and non-receivers. In a secondary analysis, we examined predictors of non-persistence in the sub-cohort of women who did not receive rt. All p values are for two-tailed tests, with statistical significance defined as p ≤ 0.05. The SAS software application (version 9.3: SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.) was used for all analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

Between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2005, 3573 women 70 years of age and older who underwent bcs for localized breast cancer in Quebec were alive, insured, and had initiated aet within 1 year after their surgery. Of those women, 168 (4.7%) received chemotherapy and 225 (6.3%) underwent mastectomy within 1 year after bcs and were thus excluded. The remaining 3180 women (mean age: 77 ± 5.2 years) constituted the study population.

In the study cohort, 28% had not received rt, 84% lived in urban areas, 81% started aet with tamoxifen (as opposed to an aromatase inhibitor), 61% had no major comorbidities (cci score of 0), and only 19% were experiencing severe material deprivation (Table iv). Examination of selected medications revealed that 46% of the cohort had used opioids, 41% had used benzodiazepines, and 8% had used antidepressants in the 3 months before aet initiation. When compared with rt receivers, rt non-receivers were generally older (mean age: 80.9 ± 5.7 years vs. 75.9 ± 4.3 years).

TABLE IV.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients

| Characteristic |

Received radiotherapy

|

Overall cohort | p Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Patients (n) | 2274 | 906 | 3180 | |

| Mean age (years) | 75.9±4.3 | 80.9±5.7 | 77.4±5.2 | <0.0001 |

| Period of diagnosis [n (%)] | 0.001 | |||

| 1998–1999 | 570 (25.1) | 281 (31.0) | 851 (26.8) | |

| 2000–2002 | 869 (38.2) | 346 (38.2) | 1215 (38.2) | |

| 2003–2005 | 835 (36.7) | 279 (30.8) | 1114 (35.0) | |

| Initially assigned aet [n (%)] | 0.004 | |||

| Tamoxifen | 1823 (80.2) | 765 (84.4) | 2588 (81.4) | |

| Aromatase inhibitor | 451 (19.8) | 141 (15.6) | 592 (18.6) | |

| cci score [n (%)]b | 0.016 | |||

| 0 | 1426 (62.7) | 527 (58.2) | 1953 (61.4) | |

| 1–2 | 742 (32.6) | 319 (35.2) | 1061 (33.4) | |

| ≥3 | 106 (4.7) | 60 (6.6) | 166 (5.2) | |

| mdi score [n (%)]c | 0.030 | |||

| Q1 (most privileged) | 447 (19.7) | 176 (19.4) | 623 (19.6) | |

| Q2 | 409 (18.0) | 135 (14.9) | 544 (17.1) | |

| Q3 | 434 (19.1) | 166 (18.3) | 600 (18.9) | |

| Q4 | 479 (21.1) | 181 (20.0) | 660 (20.8) | |

| Q5 (most deprived) | 413 (18.2) | 196 (21.6) | 609 (19.2) | |

| Not available | 92 (4.0) | 52 (5.7) | 144 (4.5) | |

| Residence [n (%)]d | 0.738 | |||

| Rural | 363 (16.0) | 149 (16.4) | 512 (16.1) | |

| Urban | 1911 (84.0) | 757 (83.6) | 2668 (83.9) | |

| Prescription medication | ||||

| Selected types [n (%)]e | ||||

| Anticonvulsant | 39 (1.7) | 20 (2.2) | 59 (1.9) | 0.353 |

| Antidepressant | 166 (7.3) | 77 (8.5) | 243 (7.6) | 0.251 |

| Benzodiazepine | 933 (41.0) | 381 (42.1) | 1314 (41.3) | 0.597 |

| Antipsychotic | 63 (2.8) | 47 (5.2) | 110 (3.5) | 0.001 |

| Opioid | 1079 (47.4) | 383 (42.3) | 1462 (46.0) | 0.008 |

| Mean concomitant (n)e | 5.9±3.6 | 6.5±4.1 | 6.1±3.7 | <0.0001 |

| Mean new starts (n)f | 13.5±8.0 | 13.0±8.3 | 13.3±8.1 | 0.172 |

| Mean hospital admissions during aet (n)f | 2.0±2.1 | 2.2±2.2 | 2.0±2.1 | <0.0001 |

Differences by radiotherapy status were evaluated by chi-square or two-sample t-tests for categorical or continuous variables respectively.

Assessed using the enhanced icd-9 coding algorithm for medical service databases by excluding icd-9 codes for breast cancer (because all women in the cohort had that condition by default).

Measures deprivation of the goods and conveniences that are part of modern life. Not available for smaller towns and rural communities.

Based on second digit of the patient’s postal code (0, rural; 1–9, urban). Assessed in the year before initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Assessed in the 3 months before initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Assessed in the 5 years after initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

aet = adjuvant endocrine therapy; cci = Charlson comorbidity index; mdi = material deprivation index.

3.2. Descriptive Outcomes

Mean time to aet initiation after bcs was 25 days (range: 14–43 days; Table v). During follow-up, 22% switched aet medications. Overall, 37% of women were censored: 8% died, 4% were lost to follow-up, and data availability ended for 25% at some point before 5 years of follow-up had elapsed. The median follow-up time was 3.7 years (interquartile range: 2.1–5 years).

TABLE V.

Descriptive outcomes over 5 years

| Outcome |

Received radiotherapy

|

Overall cohort (N=3180) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=2274) | No (n=906) | ||

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy (aet) [n (%)] | |||

| Prescriptions filled over 5 years | |||

| 1 Only | 29 (1.3) | 25 (2.8) | 54 (1.7) |

| >1 | 2245 (98.7) | 881 (97.2) | 3126 (98.3) |

| Switched medication | 532 (23.4) | 154 (17.0) | 686 (21.6) |

| Persisted with therapy for 5 years | 751 (33.0) | 250 (27.6) | 1001 (31.5) |

| Discontinued therapy | 685 (30.1) | 322 (35.5) | 1007 (31.7) |

| aet discontinuation | |||

| Rate (n/100 person–years) | 8.7 | 11.7 | 9.5 |

| Permanent [n (%)] | 432 (19.0) | 202 (22.3) | 634 (19.9) |

| Re-initiated [n (%)] | 253 (11.1) | 120 (13.2) | 373 (11.7) |

| Re-discontinued [n (%)] | 119 (5.2) | 60 (6.6 | 179 (5.6 |

| Died [n (%)] | 151 (6.6) | 108 (11.9) | 259 (8.1) |

| Lost to follow-up [n (%)]a | 51 (2.2) | 71 (7.8) | 122 (3.8) |

| Reached study end (Dec 31, 2007) before end of 5 year period [n (%)] | 636 (28.0) | 155 (17.1) | 791 (24.9) |

| Time | |||

| To aet initiation (days) | |||

| Median | 26.0 | 22.0 | 25.0 |

| irq | 15–46 | 12–39 | 14–43 |

| Follow-up (years)b | |||

| Median | 4.0 | 3.1 | 3.7 |

| irq | 2.3–5 | 1.6–5 | 2.1–5 |

| Observation (years)c | |||

| Median | 5.0 | 4.4 | 4.9 |

| irq | 3.3–5 | 2.6–5 | 3.1–5 |

| To first discontinuation (years) | |||

| Median | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Range | 0.5–3.6 | 0.4–2.9 | 0.5–3.4 |

| 5-Year mpr [n (%)]d | |||

| Overall | 1141 (50.2) | 395 (43.6) | 1536 (48.3) |

| With mean mpr ≥80% | 895 (78.4) | 300 (75.9) | 1195 (77.8) |

| 5-Year mean mprd | 0.8±0.3 | 0.8±0.3 | 0.8±0.3 |

Medical or public drug insurance ended.

From date of aet initiation and to date of censoring.

During which patient had continuous drug insurance.

Calculated only for patients with 5 years of follow-up.

irq = interquartile range; mpr = medication possession ratio.

3.3. Patterns and Predictors of AET Non-persistence

Overall, 32% of women discontinued aet, with 2% of them filling just 1 prescription. Some women discontinued aet permanently (20%); others had multiple initiations and discontinuations (12%). The overall rate of discontinuation was 9.5 episodes per 100 person–years. Compared with rt receivers, non-receivers discontinued more often (36% vs. 30%). More rt non-receivers (2.8% vs. 1.3% of rt receivers) filled just 1 prescription before discontinuing. Compared with rt receivers, rt non-receivers had a higher rate of discontinuation (11.7 episodes vs. 8.7 episodes per 100 person–years). In addition, rt non-receivers discontinued earlier than rt receivers did (median time to first discontinuation: 1.4 years vs. 1.6 years).

On multivariate analysis (Table vi), predictors of aet non-persistence included not having received rt (hr: 1.26; 95% ci: 1.09 to 1.46); age, per 10-year increase (hr: 1.15; 95% ci: 1.01 to 1.31); number of new prescriptions initiated over 5 years (hr: 1.01; 95% ci: 1.00 to 1.02); and hospital admissions over 5 years (hr: 1.08; 95% ci: 1.05 to 1.11). In other words, the risk of discontinuing aet increased by 1% for every additional medication added and by 8% for every additional hospital admission during the 5-year period. On the other hand, rural residence (hr: 0.78; 95% ci: 0.65 to 0.93) and medications at the start of aet (hr: 0.93; 95% ci: 0.92 to 0.95) lowered the risk.

TABLE VI.

Predictors of time to first discontinuation

| Predictor |

Cox analysis

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariatea | Reduced multivariateb | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| hr | 95% ci | p Value | hr | 95% ci | p Value | hr | 95% ci | p Value | |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.20 | 1.07 to 1.03 | 0.002 | 1.16 | 1.01 to 1.32 | 0.031 | 1.15 | 1.01 to1.31 | 0.039 |

| Initially assigned aet | |||||||||

| Tamoxifen | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Aromatase inhibitor | 0.81 | 0.67 to 0.98 | 0.027 | 0.88 | 0.72 to 1.08 | 0.224 | |||

| cci score | |||||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 1–2 | 0.95 | 0.83 to 1.09 | 0.485 | 0.98 | 0.85 to 1.13 | 0.774 | 0.98 | 0.85 to 1.12 | 0.729 |

| ≥3 | 1.19 | 0.91 to 1.56 | 0.207 | 1.24 | 0.93 to 1.64 | 0.137 | 1.23 | 0.93 to 1.62 | 0.151 |

| Residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 0.80 | 0.67 to 0.95 | 0.013 | 0.80 | 0.66 to 0.96 | 0.019 | 0.78 | 0.65 to 0.93 | 0.006 |

| Urban | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Prescription medication | |||||||||

| Selected types | |||||||||

| Anticonvulsant | 1.07 | 0.67 to 1.71 | 0.769 | 1.22 | 0.76 to 1.96 | 0.412 | |||

| No anticonvulsant | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Antidepressant | 0.98 | 0.77 to 1.25 | 0.894 | 1.15 | 0.89 to 1.48 | 0.280 | |||

| No antidepressant | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Benzodiazepine | 0.98 | 0.87 to 1.11 | 0.763 | 1.10 | 0.96 to 1.26 | 0.164 | |||

| No benzodiazepine | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Antipsychotic | 0.94 | 0.65 to 1.35 | 0.731 | 0.95 | 0.65 to 1.38 | 0.779 | |||

| No antipsychotic | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Opioid | 0.91 | 0.81 to 1.03 | 0.151 | 1.00 | 0.88 to 1.13 | 0.958 | |||

| No opioid | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Concomitant | 0.96 | 0.94 to 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.93 | 0.91 to 0.95 | <0.0001 | 0.93 | 0.92 to 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| New start | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.02 | 0.000 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.006 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.004 |

| Radiotherapy receipt | |||||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| No | 1.33 | 1.16 to 1.52 | <0.0001 | 1.26 | 1.09 to 1.46 | 0.002 | 1.26 | 1.09 to 1.46 | 0.002 |

| Hospital admissions during aet treatment | 1.08 | 1.06 to 1.11 | <0.0001 | 1.08 | 1.05 to 1.11 | <0.0001 | 1.08 | 1.05 to 1.11 | <0.0001 |

Adjusted for period of diagnosis and material deprivation index in addition to all other factors presented in the table.

Full model reduced by stepwise selection.

hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval; aet = adjuvant endocrine therapy; cci = Charlson comorbidity index.

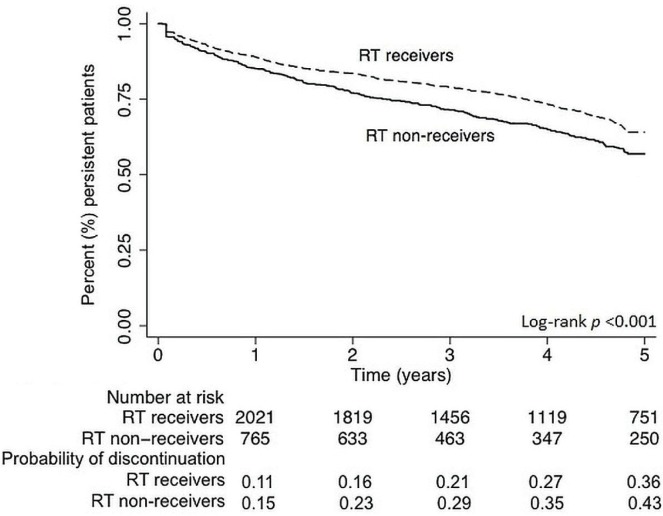

In a secondary analysis of rt non-receivers exclusively, hospital admissions during aet increased the risk for discontinuation (hr: 1.07; 95% ci: 1.02 to 1.12), and an increasing number of medications used at the start of aet decreased the risk (hr: 0.94; 95% ci: 0.91 to 0.97; Table vii). Compared with rt receivers, rt non-receivers became non-persistent significantly faster (Figure 1).

TABLE VII.

Predictors of time to first discontinuation in radiotherapy non-receivers (N=906)

| Predictor |

Cox analysis

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariatea | Reduced multivariateb | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| hr | 95% ci | p Value | hr | 95% ci | p Value | hr | 95% ci | p Value | |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.33 | 0.328 | 1.14 | 0.94 to 1.40 | 0.192 | 1.15 | 0.95 to 1.40 | 0.160 |

| Initially assigned aet | |||||||||

| Tamoxifen | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Aromatase inhibitor | 0.90 | 0.65 to 1.25 | 0.531 | 0.93 | 0.64 to 1.33 | 0.675 | |||

| cci score | |||||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 1–2 | 0.86 | 0.68 to 1.09 | 0.209 | 0.94 | 0.73 to 1.20 | 0.597 | 0.92 | 0.72 to 1.17 | 0.493 |

| ≥3 | 1.04 | 0.66 to 1.63 | 0.874 | 1.21 | 0.76 to 1.94 | 0.430 | 1.22 | 0.77 to 1.93 | 0.402 |

| Residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 0.90 | 0.66 to 1.21 | 0.470 | 0.85 | 0.62 to 1.17 | 0.324 | |||

| Urban | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Prescription medications | |||||||||

| Selected types | |||||||||

| Anticonvulsant | 1.20 | 0.57 to 2.54 | 0.637 | 1.38 | 0.64 to 2.98 | 0.419 | |||

| No anticonvulsant | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Antidepressant | 0.23 | 0.76 to 0.48 | 0.228 | 0.91 | 0.57 to 1.47 | 0.709 | |||

| No antidepressant | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Benzodiazepine | 1.02 | 0.81 to 1.27 | 0.886 | 1.15 | 0.91 to 1.46 | 0.236 | |||

| No benzodiazepine | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Antipsychotic | 0.85 | 0.49 to 1.48 | 0.569 | 0.88 | 0.50 to 1.58 | 0.674 | |||

| No antipsychotic | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Opioid | 0.94 | 0.75 to 1.17 | 0.563 | 1.03 | 0.82 to 1.29 | 0.832 | |||

| No opioid | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Concomitant | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.98 | 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.90 to 0.97 | 0.000 | 0.94 | 0.91 to 0.97 | 0.000 |

| New start | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.966 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.02 | 0.89 | |||

| Hospital admissions during aet treatment | 1.05 | 1.00 to 1.10 | 0.045 | 1.07 | 1.02 to 1.13 | 0.01 | 1.07 | 1.02 to 1.12 | 0.004 |

Adjusted for period of diagnosis and material deprivation index in addition to all other factors presented in the table.

Full model reduced by stepwise selection.

hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval; aet = adjuvant endocrine therapy; cci = Charlson comorbidity index.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for persistence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among women 70 years of age and older with localized breast cancer who initiated treatment between 1998 and 2005, stratified by radiotherapy (rt) receipt.

3.4. Patterns of AET Adherence

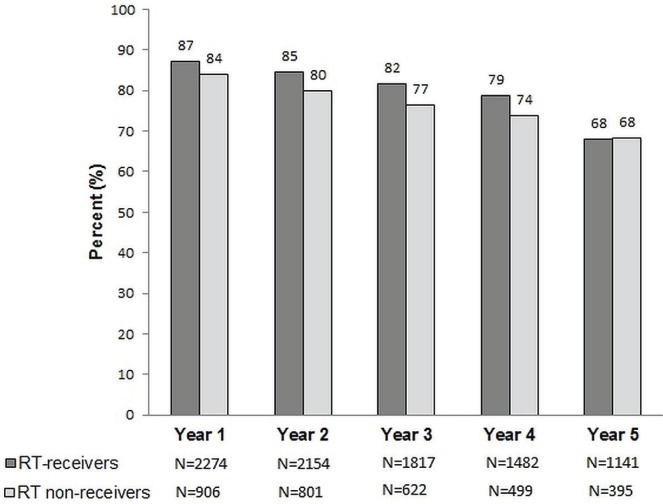

Over time, the percentage of women considered adherent (Figure 2) and the mean annual mpr (Figure 3) gradually declined for both rt receivers and rt non-receivers, without a considerable difference in the rate of decline between the two groups. However, the mean annual mpr dropped below 80% much earlier for rt non-receivers (year 3) than for rt receivers (year 5, Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of women 70 years and older attaining an annual medication possession ratio of 80% or greater, stratified by radiotherapy (rt) receipt.

FIGURE 3.

Mean annual medication possession ratio (mpr) among women 70 years of age and older with localized breast cancer who initiated treatment between 1998 and 2005, stratified by radiotherapy (rt) receipt.

4. DISCUSSION

In this prospective historical study of Quebec women 70 years of age and older treated for early-stage breast cancer with bcs, we demonstrated that 5-year persistence and adherence were suboptimal in at least one third of patients. Women who did not receive rt discontinued aet more often and earlier. In addition, those women became non-adherent earlier than did the rt receivers. Predictors of non-persistence included age, new prescription medications initiated, and hospital admissions during the 5 years of aet. Rural residence and number of concomitant medications at aet initiation lowered the risk of non-persistence.

The high discontinuation rate in this cohort was not surprising. Several studies have observed discontinuation rates ranging between 30% and 50% among women on aet6,7,9,30,31. Older women are more difficult to recruit and follow, and most studies of patients 65 years of age and older therefore have smaller sample sizes6,25,27,28,30,32–34, include women with advanced breast cancer30,32,33, or fail to achieve 5 years of follow-up7,26,32. In addition, almost no studies have evaluated the persistence and adherence to aet specifically in women 70 years of age and older who forgo rt according to guidelines. Several studies found older age to be a predictor of early aet discontinuation6,7, but that finding has received little attention. Seniors with cancer have complex comorbidities35 and tend to be more socially isolated36, to have low accrual to clinical trials37, and to be less likely to receive treatment because of their age38. Our study focused exclusively on women 70 years of age and older with early-stage cancer, in the context of the 2005 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline1, and captured nearly all incident patients meeting that description who initiated aet in Quebec.

Omitting rt after bcs is often based on the assumption that patients will be taking their aet as prescribed and for as long as prescribed. However, as did other studies, our study found that, compared with rt receivers, rt non-receivers were discontinuing more often (35.5% vs. 30.1%) and earlier (1.4 years vs. 1.6 years)7,27. That finding is concerning, because shorter durations of aet have been associated with decreased overall survival. In relation to aet completion of only 2.4 years, McCowan et al.9 reported a hr for mortality of 1.59 (95% ci: 1.14 to 2.21). Haque et al.39 demonstrated an approximately 50% reduction in the risk of subsequent breast cancer for women with the highest adherence to aet. We found that approximately 2.0% of patients filled only a single aet prescription and that 22% switched medications. Early discontinuation and a high frequency of switches might be related to treatment toxicities (in addition to other factors). Unfortunately, few studies have reported on tolerance of aet outside of clinical trials40,41.

It was not surprising that, in our study, the addition of new medications and hospitalizations over time affected persistence with aet. Consequences of an increasing number of medications over time include adverse drug effects42, and hospital admissions can result in an interruption to a woman’s daily medication-tracking routine. In addition, such events might be indicators of a change in health status. Owusu et al.6 reported an association between an increase in cci score and discontinuation of tamoxifen. Nonurban residence and concomitant medications at aet start lowered the risk of aet discontinuation. Better persistence in rural regions is probably indirectly associated with higher continuity of care. McCusker et al.43 suggested that a different mode of organization of primary care practice in rural Quebec areas, characterized by physicians being affiliated with multiple sites and a greater integration of services, ensures access to, and continuity of, care—for example, because of the possibility of seeing the family doctor at an emergency visit. Concomitant medications were associated with favourable persistence, most probably because of learned medication management habits44. In a subanalysis of rt non-receivers (28% of the cohort), only hospitalizations during aet increased the risk for discontinuation; medications at aet start decreased the risk. Surprisingly, in neither group did the presence of comorbidities assessed using the cci score influence persistence to aet.

The finding in our study that adherence progressively declined over time is also consistent with earlier observations34. We found that, compared with rt receivers, the non-receivers became nonadherent much earlier (at year 3 vs. at year 5). That observation is concerning because adherence of less than 80% has been associated with poorer survival9 and an increased risk of subsequent breast cancer39. It might therefore be helpful to identify interventions that will specifically improve adherence in women not considered for rt. Several studies have suggested that strengthened physician–patient communication might result in improved patient perceptions and beliefs about the severity of disease or the effectiveness of therapy32,45.

The joint Cancer and Leukemia Group B–Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial showed statistically significant reductions of 3% and 8% over 5 and 10 years respectively in the rate of locoregional recurrence for women treated with bcs, rt, and aet, compared with women treated with bcs and aet alone2,3. Although the absolute difference in risk reduction may not be clinically relevant in the context of competing morbidity caused by rt, the actual difference in risk reduction after adjusting for aet non-persistence and nonadherence outside of clinical trials (that is, in the general population) is unknown. Therefore, despite the practice guideline from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network1, the omission of rt for women 70 years of age and older with early-stage breast cancer remains a matter of debate. Khan et al.41 suggested that omission of rt might be most appropriate in women more than 80 years of age (rather than in women 70 years of age and older), in women with comorbidities, and in women likely to be compliant with aet.

Further research is required to determine the long-term consequences of suboptimal aet use. Careful consideration both of prior characteristics and of events occurring during the course of therapy is necessary to select the right candidates for rt omission. Haque et al.39 demonstrated a significant benefit of taking aet even if women took it irregularly. The atlas trial recently showed that continuing aet to 10 years rather than stopping at 5 years produces a further reduction in recurrence and mortality, particularly after year 104. Therefore, even if women might be struggling physically (from side effects) because of taking aet daily, encouragement to continue their aet for as long as possible may substantially reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence.

Optimizing persistence is especially important for women not considered for rt. Identification of traceable and modifiable factors such as the ones presented in the present study could trigger appropriate preventive actions when reported in time to health care teams. For example, electronic medical records could be used for surveillance of vulnerable patients. Medication reconciliation could ensure that women continue to take their aet after discharge, and prioritization of new medications could minimize the pill burden. At the same time, strengthening physician–patient communication has been considered essential34 in improving aet use.

Our study has several limitations. As with other studies that use administrative claims, we were unable to assess physician- or patient-related reasons for nonadherence and discontinuation. We defined medication possession as the presence of medication refills rather than medication at hand. It was not possible to capture women who were prescribed but who did not initiate aet (“primary nonadherence”). In addition, comorbidity as measured by cci score might underestimate the comorbidity burden in elderly patients using fewer services46. Nevertheless, we were able to capture nearly all women who initiated aet during the study period in the province. In addition, the accuracy of the Quebec prescription database has previously been determined to be more than 99% for drug, dispense date, and duration21.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that long-term persistence and adherence to aet is suboptimal in at least one third of patients 70 years of age and older with early breast cancer. Use of aet among rt non-receivers was suboptimal and worse than that observed for rt receivers. Predictors of non-persistence included age, new prescription medications initiated, and hospital admissions during the 5 years of aet. Rural residence and greater number of concomitant medications at aet initiation lowered the risk of non-persistence. In the context of the atlas and Cancer and Leukemia Group B trials, efforts to optimize persistence and adherence to aet in senior women, especially those not considered for rt, might help to improve long-term treatment outcomes.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé provided funding for this study.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no financial conflicts of interest.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2012. Ver. 3.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Berry D, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women 70 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:971–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of calgb 9343. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2382–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor–positive breast cancer: atlas, a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:805–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owusu C, Buist DS, Field TS, et al. Predictors of tamoxifen discontinuation among older women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:549–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gennari R, Audisio RA. Breast cancer in elderly women. Optimizing the treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan P, et al. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1763–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enterline PE, Salter V, McDonald AD, McDonald JC. The distribution of medical services before and after “free” medical care—the Quebec experience. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:1174–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311292892206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James PD, Wilkins R, Detsky AS, Tugwell P, Manuel DG. Avoidable mortality by neighbourhood income in Canada: 25 years after the establishment of universal health insurance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:287–96. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.047092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (ramq) Données et statistiques [Web resource] Quebec City, QC: RAMQ; n.d. [Available online at: http://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/donnees-statistiques/Pages/donnees-statistiques.aspx; accessed March 4, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamache P, Pampalon R, Hamel D. Guide méthodologique : « L’indice de défavorisation matérielle et sociale : en bref ». Quebec City, QC: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2010. [Available online at: http://www.inspq.qc.ca/santescope/documents/Guide_Metho_Indice_defavo_Sept_2010.pdf; cited March 4, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P, Raymond G. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2009;29:178–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (nchs) International Classification of Diseases. 9th rev. Hyattsville, MD: NCHS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayo NE, Scott SC, Shen N, Hanley J, Goldberg MS, MacDonald N. Waiting time for breast cancer surgery in Quebec. CMAJ. 2001;164:1133–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eifel P, Axelson JA, Costa J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, November 1–3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:979–89. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.13.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in icd-9-cm and icd-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics Canada . Glossary: Rural Delivery Area [archived Web page] Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2012. [Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/92f0138m/2007001/4054931-eng.htm; cited September 18, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ashp) AHFS Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: ASHP; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamblyn R, Lavoie G, Petrella L, Monette J. The use of prescription claims databases in pharmacoepidemiological research: the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the prescription claims database in Quebec. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00234-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. Noncompliance with congestive heart failure therapy in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:433–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420040107014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Avorn J. Compliance with antihypertensive therapy among elderly Medicaid enrollees: the roles of age, gender, and race. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1805–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.12.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–16. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:602–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis–Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:556–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3445–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:431–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedjo RL, Devine S. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:215–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huiart L, Ferdynus C, Giorgi R. A meta-regression analysis of the available data on adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer: summarizing the data for clinicians. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:325–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor—positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3309–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silliman RA, Guadagnoli E, Rakowski W, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen prescription in women 65 years and older with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2680–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demissie S, Silliman RA, Lash TL. Adjuvant tamoxifen: predictors of use, side effects, and discontinuation in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:322–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1824–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wenger GC, Davies RB, Shahtahmasebi S, Scott A. Social isolation and loneliness in old age: review and model refinement. Ageing Soc. 1995;16:333–58. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X00003457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1383–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blackman SB, Lash TL, Fink AK, Ganz PA, Silliman RA. Advanced age and adjuvant tamoxifen prescription in early-stage breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;95:2465–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haque R, Ahmed SA, Fisher A, et al. Effectiveness of aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen in reducing subsequent breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2012;1:318–27. doi: 10.1002/cam4.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fontaine C, Meulemans A, Huizing M, et al. Tolerance of adjuvant letrozole outside of clinical trials. Breast. 2008;17:376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan AJ, Haffty BG. Issues in the curative therapy of breast cancer in elderly women. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salazar JA, Poon I, Nair M. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly: expect the unexpected, think the unthinkable. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:695–704. doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCusker J, Roberge D, Tousignant P, et al. Closer Than You Think: Linking Primary Care to Emergency Department Use in Quebec. Montreal, QC: St. Mary’s Research Centre; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson TA. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:852–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, Mittal S. Adherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quam L, Ellis LB, Venus P, Clouse J, Taylor CG, Leatherman S. Using claims data for epidemiologic research: the concordance of claims-based criteria with the medical record and patient survey for identifying a hypertensive population. Med Care. 1993;31:498–507. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]