Abstract

Objective

Elevation of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TGRL) contributes to the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Our work has shown that TGRL lipolysis products in high physiological to pathophysiological concentrations cause endothelial cell injury; however, the mechanisms remain to be delineated.

Approach and Results

We analyzed the transcriptional signaling networks in arterial endothelial cells exposed to TGRL lipolysis products. When human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) in culture were exposed to TGRL lipolysis products, activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) was identified as a principal response gene. Induction of ATF3 mRNA and protein was confirmed by qRT-PCR and western blot. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that ATF3 accumulated in the nuclei of cells treated with lipolysis products. Nuclear expression of p-JNK, previously shown to be an initiator of the ATF3 signaling cascade, also was demonstrated. siRNA-mediated inhibition of ATF3 blocked lipolysis products-induced transcription of E-selectin and IL-8, but not IL-6 or NFκB. c-Jun, a downstream protein in the JNK pathway was phosphorylated while expression of NFκB-dependant JunB was down-regulated. Additionally, JNK siRNA suppressed ATF3 and p-c-Jun protein expression suggesting that JNK is up-stream of the ATF3 signaling pathway. In vivo studies demonstrated that infusion of TGRL lipolysis products into wild type mice induced nuclear ATF3 accumulation in carotid artery endothelium. ATF3−/− mice were resistant to vascular apoptosis precipitated by treatment with TGRL lipolysis products. Also peripheral blood monocytes isolated from postprandial humans had increased ATF3 expression as compared to fasting monocytes.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that TGRL lipolysis products activate ATF3-JNK transcription factor networks and induce endothelial cells inflammatory response.

Keywords: Lipoprotein, inflammation, activating transcription factor 3, oligonucleotide arrays, lipolysis

Elevation of TGRL is a known ASCVD risk factor and can induce endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. Although epidemiological evidence has shown a clear link between hypertriglyceridemia and atherogenesis1, the mechanism of vascular injury related to elevated TGRL remains incompletely understood. TGRL are hydrolyzed on the endothelial cell surface by lipoprotein lipase, thus potentially inducing very high concentrations of lipolysis products along the blood-endothelium interface. Increased concentrations of TGRL lipolysis products may contribute to the pathogenesis of ASCVD by affecting the expression of multiple pro-inflammatory, pro-coagulant, and pro-apoptotic genes.

In our studies, pro-inflammatory pathways are activated and predominate when endothelial cells are exposed to high physiological and pathophysiological concentrations of TGRL lipolysis products, but not TGRL alone2–4. TGRL lipolysis releases neutral and oxidized free fatty acids (FFAs) that induce endothelial cell inflammation5. Also, we have found that TGRL lipolysis products injured endothelial cells by increasing VLDL remnant deposition in the artery wall, augmented endothelial monolayer permeability, perturbed zonula occludens-1 and F-actin, and induced apoptosis6–7. TGRL lipolysis products also significantly increased the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in endothelial cells and altered lipid raft morphology8. Thus, TGRL lipolysis products in high physiological and pathophysiological concentrations have multiple pro-inflammatory actions on endothelial cells.

The p38 and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) subset of MAP kinase signaling is a key cellular stress response pathway leading to induction of apoptosis9. Induction of this pathway has been documented using a variety of physiochemical stressors in several cell types including endothelial cells10–12. Signaling through small G proteins such as Rac, Rho, Ras, and cdc42 activates MEKK pathways leading to phosphoactivation of JNK and subsequent nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation of several genes13–15. Activated JNK also phosphorylates c-Jun, a component of the AP-1 transcription complex. Response elements induced by JNK signaling include the CREB family that contains additional AP-1 associated activating transcription factor isoforms16.

We hypothesized that TGRL lipolysis products activate stress response pathways that induce expression of multiple pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic genes leading to endothelial dysfunction. Our studies identified transcription of ATF3, a member of the CREB family, as a key response gene after treatment with TGRL lipolysis products and demonstrated that its induction was essential for the expression of a subset of pro-inflammatory responses. Thus, ATF3 could represent a key regulatory protein in TGRL lipolysis product-mediated vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Results

TGRL lipolysis products activate genes encoding transcription factors and pro-inflammatory activities

The response of the HAEC transcriptome to media, LpL, TGRL, or TGRL lipolysis products (TGRL + LpL) was determined with high-density oligonucleotide arrays containing 22,000 probe sets (Human Genome U133A2.0 array, Affymetrix) that represent a large fraction of the expressed human genome. Transcription of approximately 14,500 genes was reliably detected (detection P≤0.05) in all treatment groups with no significant difference in gene numbers evident between groups. Table I in the online-only Data Supplement records the percentage of genes altered by LpL or TGRL or TGRL + LPL and Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement depicts the functional classifications for the affected genes. Verification of the gene chip results with qRT-PCR are depicted in Figures IIA & B in the online-only Data Supplement. Specific genes sensitive to TGRL lipolysis treatment are listed in Tables II & III in the online-only Data Supplement.

TGRL lipolysis products activated genes encoding transcription factors including CREM (2-fold), REL (2-fold), Jun (3.5-fold), JunB (8.6-fold), CEBPB (4.9-fold), activating transcription factors 3 (ATF3) (36.8-fold) and ATF4 (2.1-fold) (Table III in the online-only Data Supplement). Transcription of nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (NFKBIA/IκBA), an inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappa-B (NFκB) action, was increased 4.3-fold while Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) was increased 7-fold. Proinflammatory genes activated included E-selectin (7-fold), IL-1α (4-fold), IL-8 (6.1-fold) and VEGF (3.5-fold).

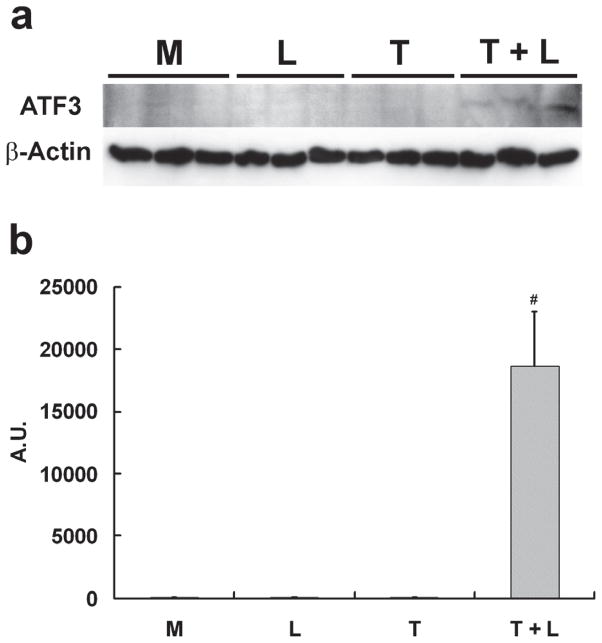

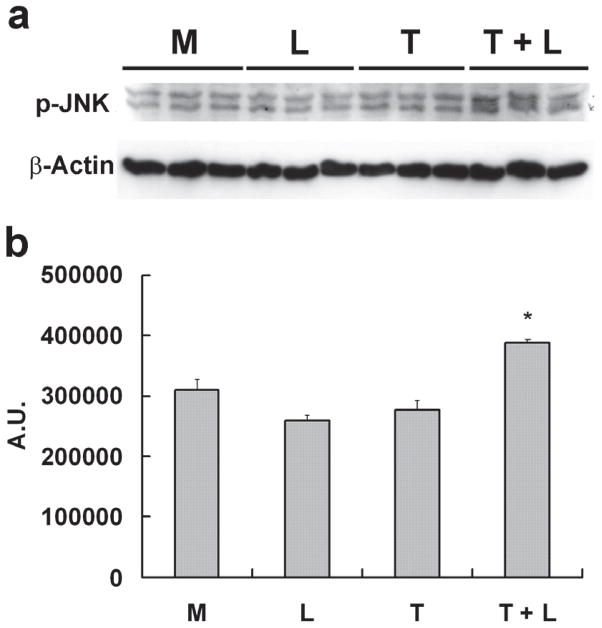

TGRL lipolysis products induce ATF3 and p-JNK protein expression and activate the SAPK/JNK pathway

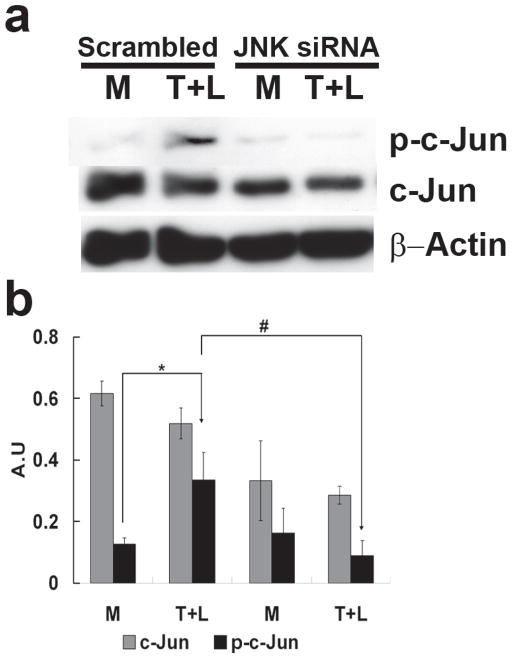

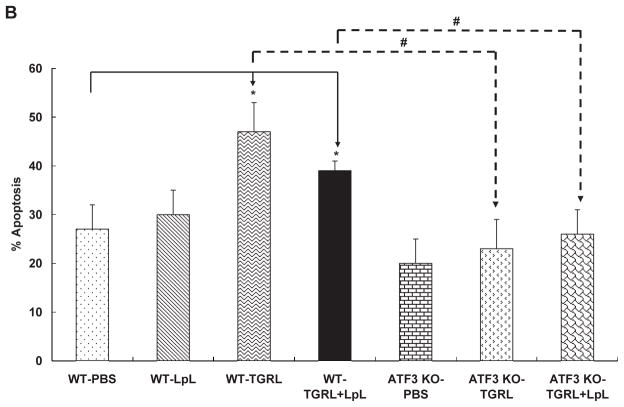

Western blot analysis showed lipolysis product treatment induced ATF3 and p-JNK protein expression (Fig 1A & B). To determine the selectivity of p-JNK activation, we evaluated downstream proteins of this pathway. Compared with control treatments, only lipolysis products significantly increased expression of c-Jun and p-c-Jun (Fig 1C). Despite increased mRNA transcription of JunB (associated with NFκB signaling), protein expression was down-regulated by lipolysis products treatment (Fig 1C).

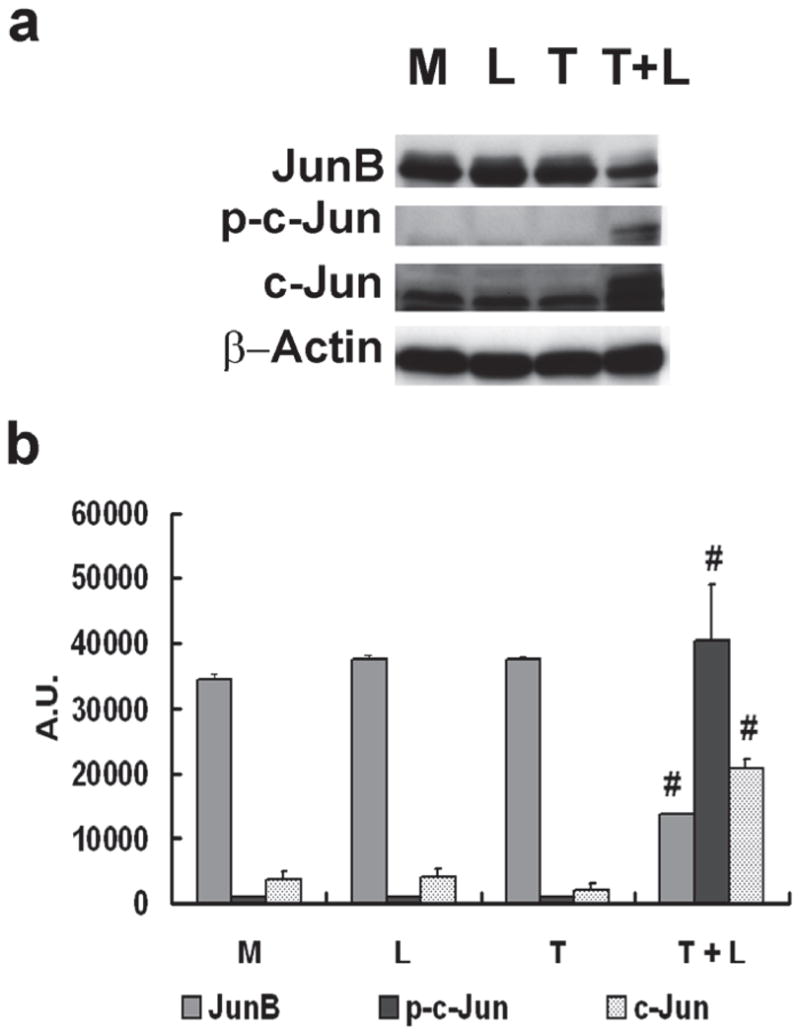

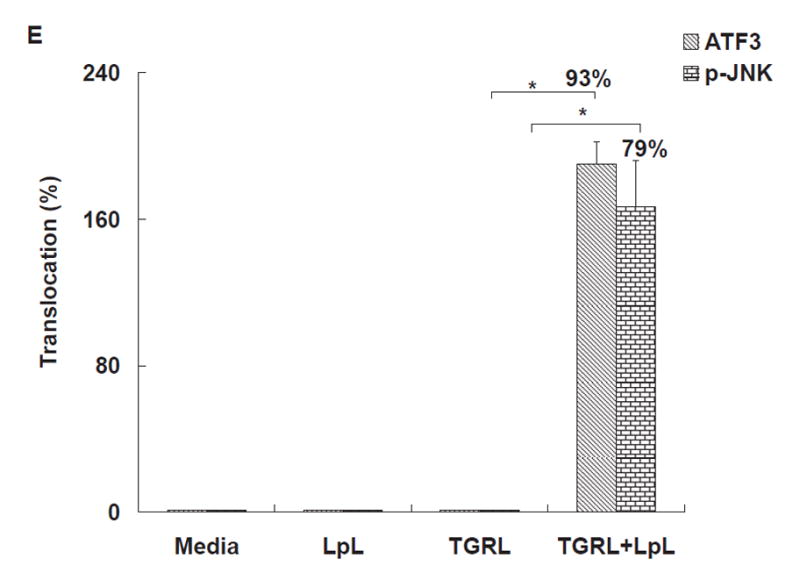

Figure 1. TGRL lipolysis products increase ATF3, p-JNK, p-c-Jun, and c-Jun protein expression and translocation of ATF3 and p-JNK from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.

HAEC were exposed to TGRL lipolysis products (T+L), media (M), LpL (L), or TGRL (T) for 3 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting (a) and (b) densitometry. A) Protein expression of ATF3 after the 4 treatments described above; B) Protein expression of p-JNK; C) Protein expression of c-Jun, phosphorylated c-Jun (p-c-Jun), and JunB. For A–C, n=3, # P≤0.05, T+L compared to M, L, or T. D) Immunofluorescence images of ATF3 and p-JNK showing transition of cytosolic to nuclear localizationtranslocation of ATF3 and p-JNK from the cytoplasm to the nucleus following lipolysis product exposure (Bar = 40 μm). DAPI for nucleus stain. E) Percentage of cells with nuclear staining for ATF3 and p-JNK following lipolysis product exposure, n=5 coverslips/treatment group, *P≤0.04 for comparisons between TGRL + LpL to TGRL alone.

Cellular location of ATF3 and p-JNK also changed in response to lipolysis product treatment. In cells treated with only TGRL or LpL, ATF3 and p-JNK were present at very low levels and not concentrated in the nucleus (Fig 1D). After 3 h of TGRL + LpL treatment, ATF3 and p-JNK production were up-regulated with rapid accumulation in nuclei. Following TGRL + LpL treatment, 93% and 79% of cells had nuclei which stained positive for ATF3 and p-JNK, respectively (Fig 1E). Our observations are consistent with previous studies that show ATF3 is expressed at a low level in normal and quiescent cells but can be rapidly induced in response to extracellular signals and is involved in controlling a wide variety of stress-related cellular activities17–19.

ATF3 siRNA suppresses induction of a subset of inflammatory genes

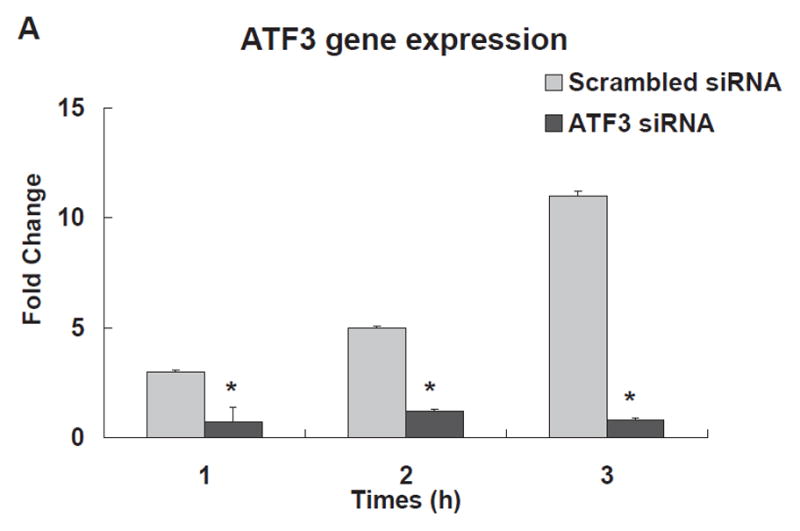

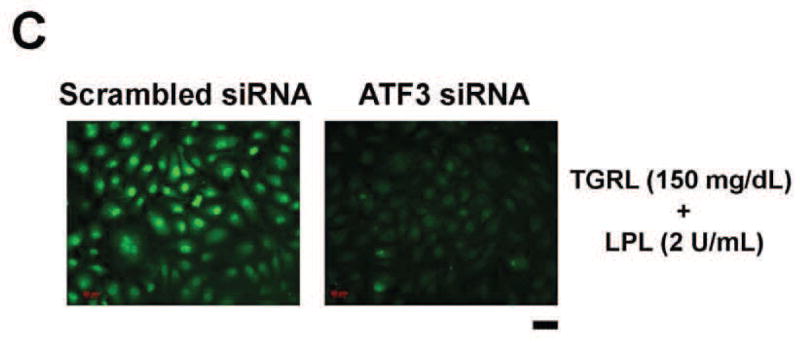

To determine the relationship between ATF3 and induction of pro-inflammatory gene networks, we performed 18 h ATF3 siRNA (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA) knockdown experiments in HAEC treated with TGRL+ LpL for 1, 2, and 3 h. In scrambled siRNA-treated HAEC, ATF3 expression was up-regulated significantly after treatment with lipolysis products for up to 3 h (Fig 2A). Oligo-based siRNA targeting effectively decreased the amount of ATF3 mRNA (90%) in HAEC after 3 h of lipolysis product treatment (Fig 2B) Immunofluorescence analysis also showed that siRNA knockdown in HAEC attenuated ATF3 protein expression (Fig 2C).

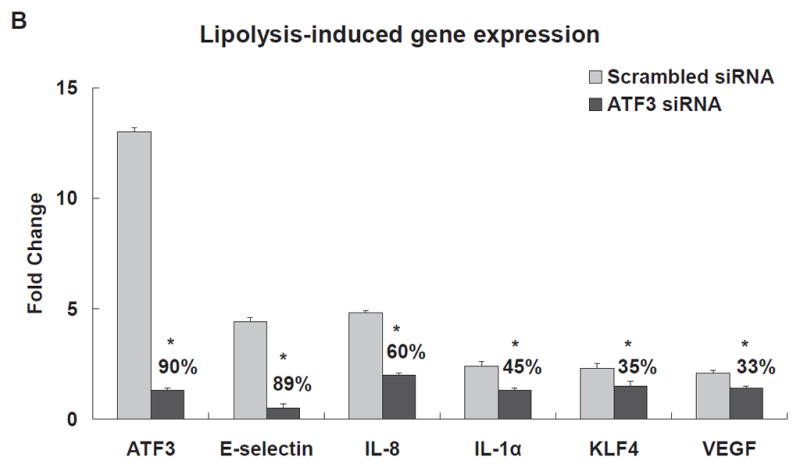

Figure 2. Effect of ATF3 siRNA.

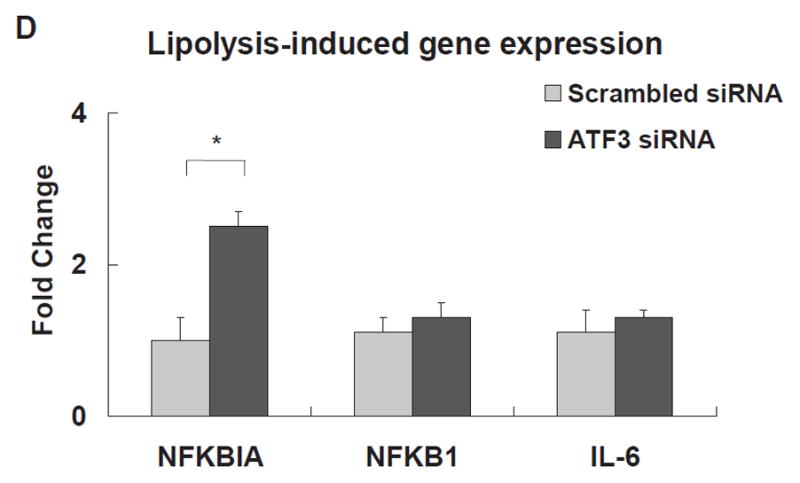

The expression of each gene was normalized to that of GAPDH and the fold change was calculated as the difference in expression with TGRL lipolysis products in the presence of scrambled siRNA and ATF3 siRNA (n = 3, *P≤0.05). Samples pretreated with siRNA 18 h prior to lipolysis product exposure A) Effect of ATF3 siRNA relative to time on ATF3 levels. B) Alterations in the transcription of ATF3, E-selectin, IL-8, IL-1α, KLF4 and VEGF, C) ATF3 protein expression, as monitored by immunofluorescence was suppressed by ATF3 siRNA (Bar = 40 μm). D) Alterations of NFKBIA, NFKB1 and IL-6 gene expression.

The transcription of mRNAs encoding E-selectin, IL-8, IL-6, NFKBIA/IκBA, and NFKB1/NFκB(p50) was quantified in ATF3 siRNA transfected cells. ATF3 blockade resulted in a large and significant decrease in lipolysis product-induced E-selectin (89%) and IL-8 (60%) mRNA levels (Fig 2B). Similar results were retained with a different construct of ATF3 siRNA (IDT, Coralville, IA; Figure IIIA & B in the online-only Data Supplement). IL-1α, KLF4, and VEGF transcription also were moderately decreased (Fig 2B). siRNA inhibition of ATF3 did not alter lipolysis product induction of NFKB1 or IL-6 (Fig 2D); the latter is known to be regulated by NFκB. Also, knockdown of ATF3 after lipolysis product treatment significantly increased NFKBIA. These data suggest a specific and possibly a novel activating effect of endothelial cell ATF3, a transcription factor that was initially identified as a repressive transcription factor for E-selectin and IL-8 expression.

JNK siRNA decreased ATF3 expression

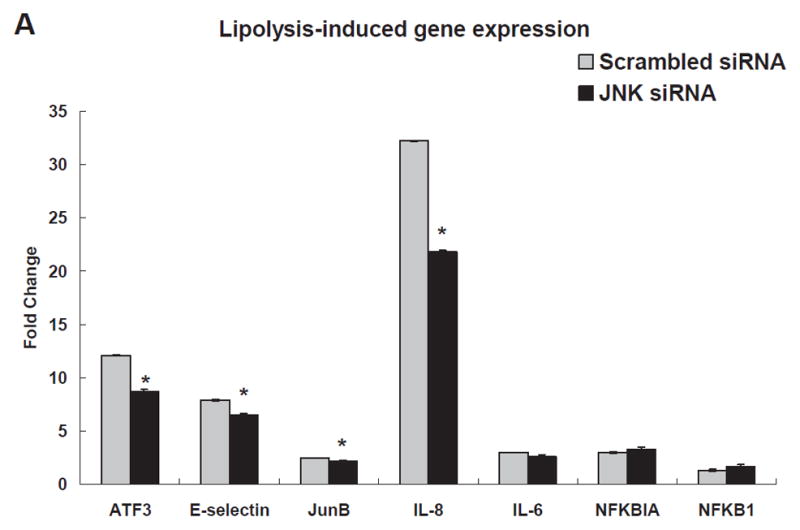

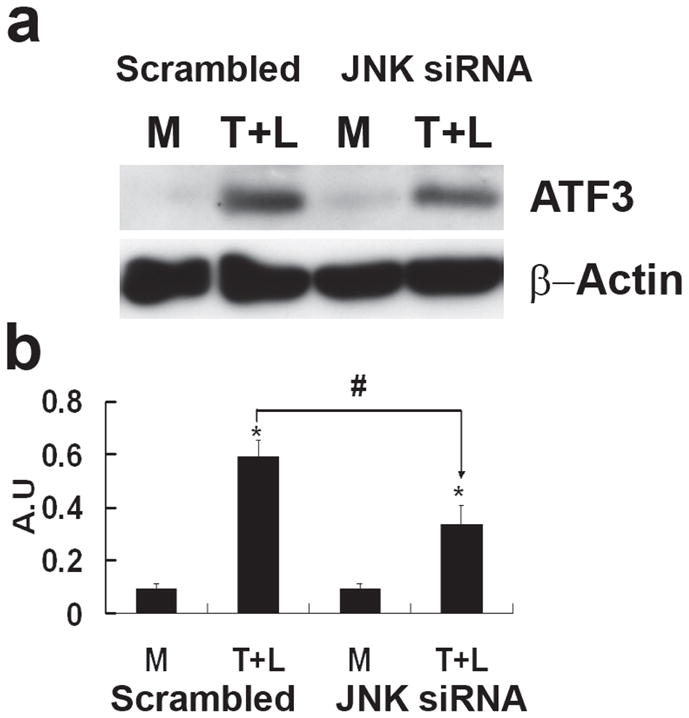

To examine the association between JNK activation and ATF3 expression, we transfected HAEC with scrambled siRNA or JNK siRNA for 48 h followed by treating cells with TGRL + LpL for 3 h. JNK siRNA significantly repressed transcription of JNK (80%) (Figure IVA in the online-only Data Supplement), compared to scrambled siRNA. The JNK siRNA treatment also produced a decrease in JNK protein (Figure IVB in the online-only Data Supplement). siJNK resulted in significantly decreased ATF3, E-selectin, JunB and IL-8 mRNA expression (Fig 3A). In contrast, mRNA expression of IL-6, NFKBIA/IκB and NFKB1/NFκB were not altered by JNK siRNA (Fig. 3A). JNK siRNA transfection significantly decreased lipolysis product-induced protein expression of ATF3 and p-c-Jun (Fig 3B & 3C). In contrast, lipolysis product-induced increase of c-Jun protein expression was not significantly altered by JNK knockdown. A different construct of JNK siRNA produced similar results (Figure VA & B in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 3. Effect of JNK siRNA on gene transcription and translation.

A) Alterations in gene transcription is normalized to that of GAPDH with fold changes calculated as the difference in expression of factors in the presence of TGRL lipolysis products and the exposure to either scrambled siRNA and JNK siRNA. Cells were exposed to siRNA 48 h prior to lipolysis product treatment (n=3, *P≤0.05) B) Alterations in ATF3 protein C) Alterations in p-c-Jun and c-Jun. For both B and C, (a) western blot, (b) densitometry quantification; n=3, *P≤0.05 for comparisons between scrambled siRNA exposed to M and T+L or JNK siRNA exposed to M and T+L; # P≤0.05 difference between T+L in scrambled siRNA and JNK siRNA.

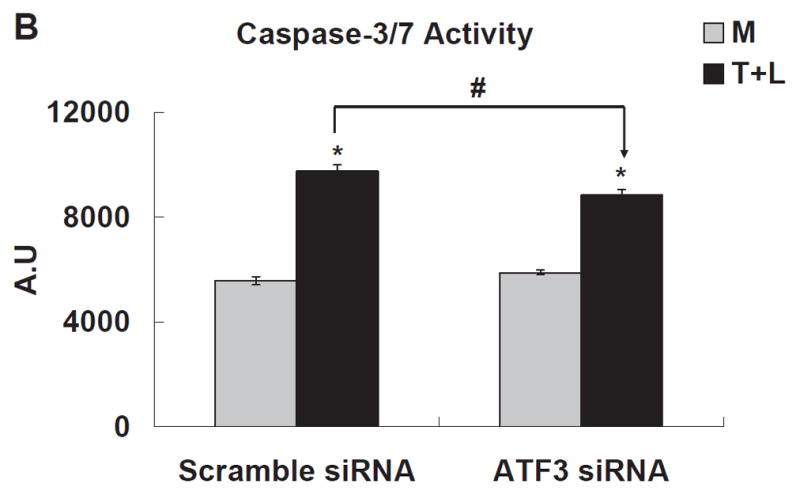

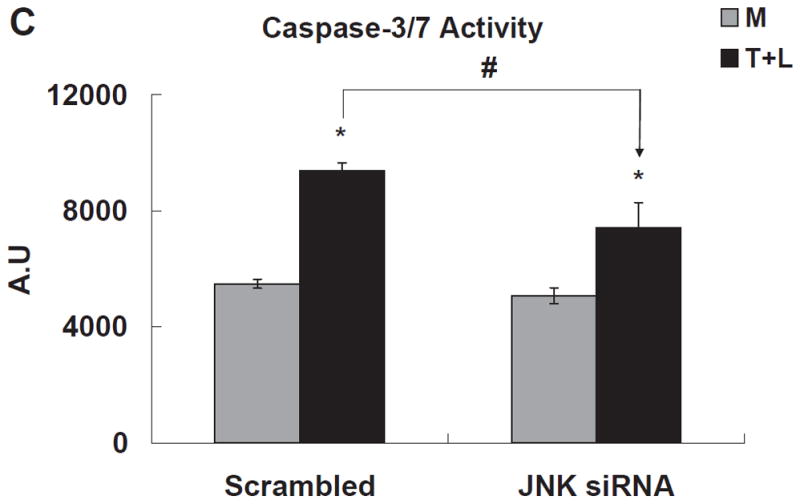

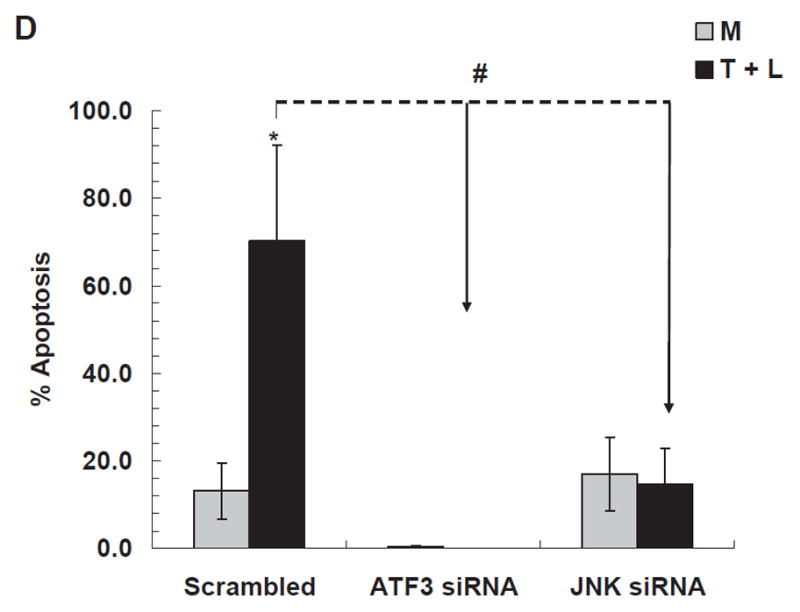

Both ATF3 and JNK contribute to TGRL lipolysis product-induced endothelial cell apoptosis

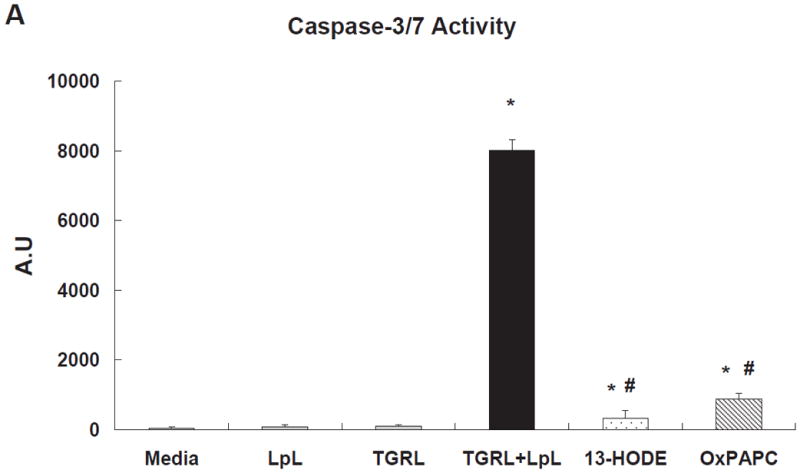

TGRL lipolysis products increased caspase-3/7 activity significantly 3 h after treatment (Fig 4A). Two lipids previously characterized as injurious to endothelium, 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-3-glycero-phosphorylcholine (oxPAPC, 40 μg/mL) and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE, 50 μM) also significantly increased caspase-3/7, but to a much lesser extent than TGRL lipolysis products. Additionally, both ATF3 siRNA (Fig 4B) and JNK siRNA (Fig 4C) significantly suppressed lipolysis products-induced caspase-3/7 activity. Figure 4D shows the results of a different measure of apoptosis, a TUNEL assay, which again depicts the involvement of ATF3 and JNK in lipolysis induced apoptosis. A set of representative images relative to the TUNEL assay are recorded in Figure VI in the online-only Data Supplement.

Figure 4. TGRL lipolysis increased apoptosis as measured by caspase-3/7 & TUNEL assays.

A) Caspase-3/7 activity was significantly increased with TGRL lipolysis (TGRL + LpL) after 3 h of incubation. * = TGRL + LpL compared to media, LpL, or TGRL alone and oxPAPC or 13-HODE compared to media; # = oxPAPC (40 μg/mL) or 13-HODE (50 μM) compared to TGRL + LpL treatment.

B) The caspase-3/7 activity significantly decreased in HAEC pre-treated with ATF3 siRNA transfected for 18 h.

C) HAEC transfected with JNK siRNA for 48 h and treated with TGRL lipolysis products for 3 h. * = TGRL + LpL compared to media; # = scrambled compared to either ATF3 or JNK siRNA treatment for T+L. For A, B and C, N=5 treatments/group, P≤0.05,

D) TGRL lipolysis product-induced apoptosis is significantly reduced by ATF3 siRNA and JNK siRNA. N=4 treatments/group, *P≤0.05 compared to Media control, #P≤0.05 scrambled compared either ATF3 or JNK siRNA treatment for T+L assayed by TUNEL.

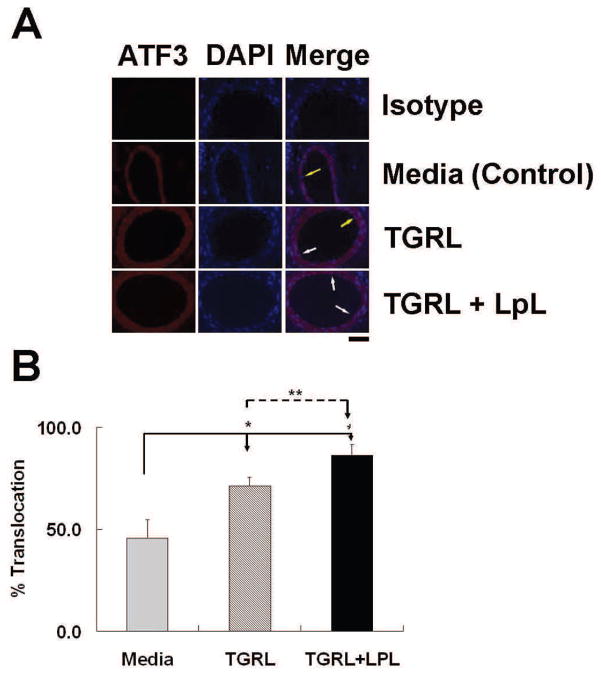

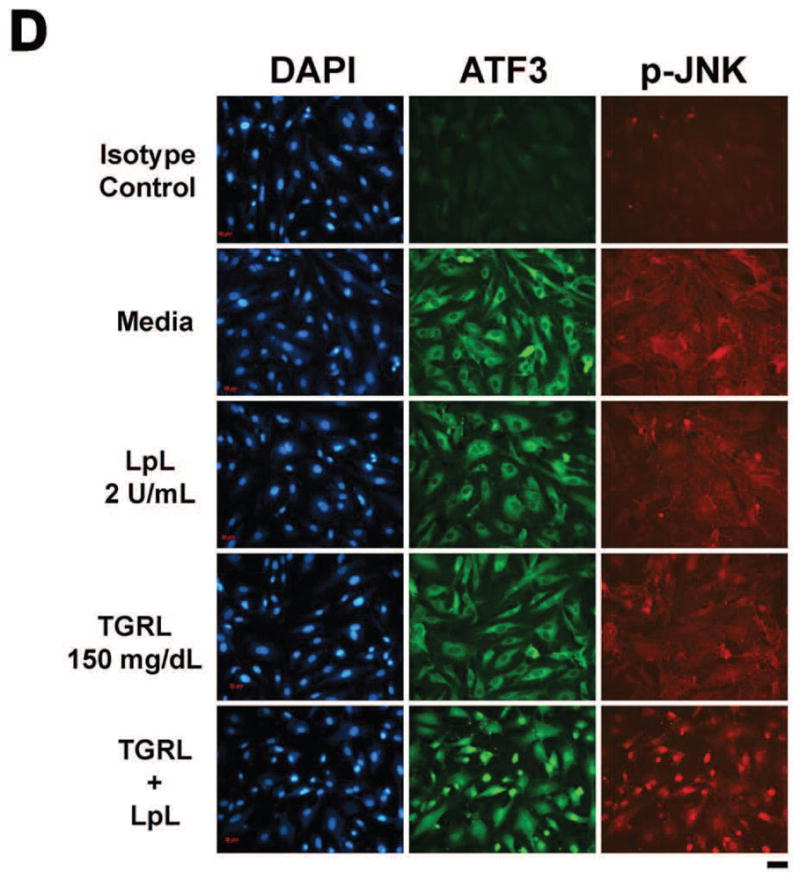

Infusion of lipolysis products activates ATF3 in intact carotid arteries

To determine the applicability of cell culture results to intact tissues, we treated mouse carotid arteries in situ by cardiac puncture and perfuse with media, TGRL, or TGRL lipolysis products. As shown in Fig 5A, ATF3 was present at very low levels in arterial cell cytoplasm in media-treated C57BL/6 mice but was extensively expressed and accumulated in the nucleus of carotid endothelial and medial cells from TGRL lipolysis products-infused mice. Counts of ATF3 positive nuclei by a treatment-blinded observer confirmed that the nuclear accumulation of ATF3 was significantly higher in carotid arteries perfused with TGRL lipolysis products relative to media or TGRL alone (Fig 5B). These results demonstrate that activation of ATF3 in response to TGRL lipolysis occurs in the endothelium of intact vessels.

Figure 5. TGRL lipolysis products activate ATF3 expression in mouse carotid arteries.

A) Immunostaining for ATF3 protein expression; B) Quantitative evaluation of ATF3 expression in the mice carotid arteries after perfusion with media alone, TGRL alone, or TGRL lipolysis (TGRL + LpL) for 15 min. N = 4 mice/group, *P≤0.02, **P≤0.05. Original magnification 60X. White arrow (ATF3 accumulation in nucleus), yellow arrow (nuclear staining absent).

Mice genetically deficient in ATF3 (ATF3−/−) fail to activate carotid artery endothelial cell apoptosis in response to treatment with lipolysis products

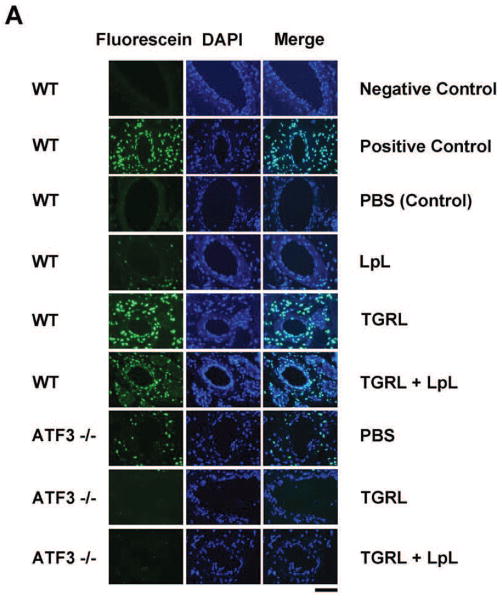

We asked whether lipolysis products induce vascular apoptosis in vivo and whether this is ATF3 dependent. TUNEL staining of carotid arteries 3h after femoral vein infusion showed apoptotic endothelial cells in carotid arteries of male C57BL/6 mice treated with either TGRL or TGRL lipolysis products. TUNEL staining (Fig 6A) was not present in carotid artery endothelium from mice injected with either PBS or LpL alone. Counts of endothelial cells showed carotid arteries perfused with TGRL alone and TGRL lipolysis products had significantly increased numbers of apoptotic cells (47% and 30%) compared to PBS control (Fig 6B). There was no statistical difference in apoptosis induced by TGRL alone compared to TGRL lipolysis products. We reasoned that TGRL underwent lipolysis as a result of interacting with endogenous LpL, thus increasing endothelial cell apoptosis. ATF3−/− mice had no increase in the incidence of apoptosis in response to either TGRL or TGRL lipolysis products infusion.

Figure 6. TGRL lipolysis product-induced apoptosis is reduced in ATF3−/− mouse carotid arteries.

A) TUNEL staining of mouse carotid artery; B) % apoptosis of endothelial cell based on FITC and nuclear staining. Both TGRL (47%) and TGRL lipolysis (TGRL + LpL) (39%) significantly induced apoptosis compare to PBS control only in WT carotid arteries, not in ATF3−/− mice. Positive control: DNAse I treated; Negative control: without rTdT enzyme. N = 4 mice/group, *P≤0.05 compared to PBS control of WT mice, #P≤0.05 ATF3−/−compared to WT treatment group. Bar = 20μm.

ATF3 expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

We previously have shown that ingestion of a moderately high-fat meal or treatment with TGRL lipolysis products activates monocytes and causes lipid droplet formation20. Results of the present study suggest augmented ATF3 mediated inflammatory responses in the postprandial state. We compared ATF3 and cytokine (IL-6 and CCL-2) gene expression in fasting and postprandial PBMC isolated from healthy individuals. mRNA expression of ATF3, IL-6, and CCL-2 (MCP-1) were increased 1.6, 1.9 and 3.4-fold (Figure VII in the online-only Data Supplement) in postprandial PBMC compared to expression in PBMC from fasting individuals. This work suggests that even a single moderately high-fat meal with increased generation of TGRL lipolysis products can regulate monocyte gene expression to enhance pro-inflammatory pathways.

Discussion

Our experiments demonstrated a robust pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic response when endothelial cells were treated with TGRL lipolysis products in high physiological to pathophysiological concentrations. Among the 266 genes induced by lipolysis products, the two largest categories were transcription factors (23%) and inflammation (11%). The next largest categories were related to protein binding, signaling pathways, and cell cycle alterations. Four genes involved in cell stress response pathways, c-Jun, JunB, CEBPB, and ATF3 were highly expressed in TGRL lipolysis-treated cells.

The four major MAP kinase pathways, ERK, JNK, P38, and BMK/ERK5, perform activating phosphorylations of nuclear transcription factors. Of these, ERK has been shown to inhibit ATF3 expression while JNK activates ATF3 through transcriptional regulation12. JNK activation also results in phosphorylation of c-Jun, a component with ATF3 of a complex that binds AP-1 responsive promoter regions. While both ATF3 and c-Jun promote apoptosis21, this is opposed by JunB, another transcription factor activated through the NFκB pathway. CEBPB acts to amplify NFκB mediated IL-6 transcription through epigenetic modulation at the interface between ATF3 and NFκB signaling22.

Previous studies have shown up regulation of ATF3 to act as either pro-inflammatory23 or anti-inflammatory24–26. The dimeric state of ATF3 gives us clues as to the ultimate effects of ATF3 on inflammation. As a homodimer, ATF3 acts as a transcriptional regulator inhibiting expression of pro-apoptotic molecules. Alternatively, ATF3 can form a heterodimer with activated c-Jun that enhances transcription of stress response genes27. Cellular responses to increases in ATF328, c-Jun16, and JunB27, 29 reflect the increased probability of these factors interacting with promoter sites independently or in combination27, 29. Our results suggest lipolysis of TGRL initiates JNK-mediated signaling that drives ATF3 complexes towards pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory responses through formation of a phospho-c-Jun/ATF3 AP-1 binding complex. Furthermore, although JunB mRNA levels increase, protein levels are decreased in lipolysis product-exposed cells. JNK regulates the turnover of both c-Jun and JunB by phosphorylation-dependent activation of the E3 ligase Itch30–31. Since JunB is associated with NFκB signaling, increased transcription of IκBA, and down-regulation of JunB in response to lipolysis products emphasizes inhibition of NFκB signaling. Correlatively, siRNA knockdown of ATF3 was without effect on the NFκB associated expression of IL-6. In general, JNK activation in endothelial cells is considered a pro-apoptotic event, while NFκB promotes cell survival. This observation also implies a predominance of pro-apoptotic responses that correlate well with our previous demonstration that lipolysis products induce apoptosis in HAEC7.

siRNA knockdown experiments suggest the apoptotic response depends on both JNK and ATF3. This is correlated with prevention of carotid apoptosis in ATF3 −/− mice treated with lipolysis products. JNK siRNA decreased ATF3, E-selectin, JunB, and IL-8 transcription. Similarly, ATF3 siRNA decreased E-selectin and IL-8 transcription but was without effect on NFκB associated genes. These results suggest that JNK is an upstream regulator of AP-1 signaling through both phosphorylation of c-Jun and transcription of ATF3. We performed JNK siRNA experiments with 2 sequences with both treatments demonstrating significant but partial reduction in ATF3 expression (Fig 3 and Figure V in the online-only Data Supplement). This suggests that JNK signaling augments constitutive ATF3 expression through uncertain mechanisms that could include transcriptional activation by an unidentified transcription factor or mRNA stabilization. As a consequence, expression of both JNK and ATF3 is important in stimulating vascular inflammation through ATF3/c-Jun-mediated up-regulation of IL-8 and E-selectin.

Our microarray data suggest a 30-fold induction of the superoxide dismutase 3 gene (SOD3), 10-fold induction of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, also known as COX2, (Table III in the online-only Data Supplement), which are oxidative stress response genes. A related gene phospholipase A2 (PLA2G6) had a 2-fold induction. A recent study suggests cross-talk between PLA2 and the MAP kinase pathway32. These systems interact principally to increase the duration of JNK signaling with prolonged signaling necessary for induction of apoptosis. In contrast, decreased JNK signaling is regulated through NFκB mediated up-regulation of a variety of inhibitors of JNK activation including TRADD inhibitors, iron, and ROS scavengers, and specific inhibitors of activating enzymes involved in JNK signaling33. The constellation of findings in our study implies lipolysis products create an imbalance between MAPK-JNK and NFκB pathways that favor ATF3/AP-1 mediated inflammation and apoptosis.

A number of other biological molecules and pathways could contribute to the pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic effects of TGRL lipolysis products. For example, key inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes were up-regulated by lipolysis products including IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, and PPARγ. Most of these genes activate monocytes and/or endothelial cells. IL-1α is likely pivotal in inflammatory activation as it has been shown to act as an autocrine stimulus up-regulating IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF in complement-treated endothelium34–35. In addition, three leukocyte adhesion molecules, E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1, were up-regulated by lipolysis products. Further, induction of IL-8 and CCL-2 (MCP-1) have been shown to be increased by oxPAPC36. oxPAPC is a prototypic biologically active oxidized phospholipid first isolated from minimally modified LDL and OxPAPC is a known stimulator of ATF337. Also, 13-HODE is the most prevalent oxylipid in atherosclerotic plaque, a TGRL lipolysis product5, and is a ligand for PPARs38–39. More studies are needed to further define pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors in lipolysis products.

ATF3 has been reported to be the transcriptional inhibitor responsible for PPAR activator modulation of E-selectin up-regulation in response to TNFα40. In contrast to prior reports suggesting an inhibitory role for ATF3 in inflammation, we found ATF3 expression was necessary for induction of some, but not all, pro-inflammatory responses to lipolysis product treatment. In particular, transcription of IL-1α, E-selectin, IL-8, and VEGF were inhibited by ATF3 siRNA. In contrast, ATF3 inhibition had no effect on IL-6 or NFκB transcription suggesting a complex inter-relationship between these two pathways.

Lipolysis activated cellular apoptosis was suppressed by pre-treatment with ATF3 siRNA. After knock down of ATF3, cell viability was significantly increased compared to scrambled siRNA treated cells. This suggests that ATF3 inhibits cell growth and could reflect its pro-apoptotic properties. It also suggests that there is basal expression of the ATF3 gene that may contribute to the phenotype of endothelial cells. Furthermore, JNK siRNA also suppressed lipolysis products-induced mRNA expression of ATF3, E-selectin, JunB and IL-8 and decreased protein expression of ATF3 and p-c-Jun. Knockdown of JNK also suppressed apoptosis. These results suggest that JNK signaling is upstream of ATF3.

Experiments in cell culture are inherently limited by the altered extracellular context and absence of multi-cell interactions. We performed two experiments with mice asking whether our findings in vitro were applicable to tissues from living animals. In this study, infusion of lipolysis products into carotid arteries confirmed up-regulation and nuclear accumulation of ATF3 in endothelium and cells of the media in intact vessels. The second experiment demonstrated activation of apoptosis in endothelial cells of carotid arteries in mice infused with either TGRL or TGRL lipolysis products intravenously. The activation of apoptosis in these in vivo studies appeared to be dependent on ATF3 activity as mice genetically deficient in ATF3 did not have a vascular apoptosis response to lipolysis product infusions. Activation of apoptosis in vivo by TGRL alone suggests that endogenous lipolysis is sufficient to generate products that injure endothelium. We did not test the ability of in vivo infusion of lipolysis products to induce carotid inflammation in this study. Our findings correlate with previous demonstration of ATF3 expression in association with apoptosis in atherosclerotic plaques41.

Our study with human peripheral blood monocytes suggests a dynamic up-regulation of ATF3 correlated with monocyte cytokines expression in the postprandial state of a moderately high-fat meal. Since expression of lipoprotein lipase is thought to be a local process regulated by specific tissues, the concept that hypertriglyceridemia could lead to increased concentrations of lipolysis products at the blood-endothelial cell interface is an intriguing phenomenon that deserves further study.

In conclusion, our study showed a robust and rapid induction of transcription factor ATF3-related genes in the JNK pathway and cytokines associated with AP-1 signaling in endothelial cells treated with TGRL lipolysis products. Further, our mouse carotid artery and monocyte experiments documented the pathophysiological relevance of our observations. These studies indicate that high physiological to pathophysiological concentrations of TGRL lipolysis products can cause vascular inflammation and apoptosis that potentially renders the artery more susceptible to the development of atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Elevation of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TGRL) contributes to the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and can induce endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. Our studies identified transcription factor ATF3, a member of the CREB family, as a key response gene after treatment with TGRL lipolysis products and demonstrated that its induction was essential for the expression of a subset of pro-inflammatory responses. These findings correlate with previous demonstration of ATF3 expression in association with apoptosis in atherosclerotic plaques. This study demonstrates that TGRL lipolysis products activate ATF3-JNK transcription factor networks and induce endothelial cells inflammatory response. Thus, ATF3 could represent a key regulatory protein in TGRL lipolysis product-mediated vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tsonwin Hai, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH for providing ATF3 deficient mice.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the NIH-HL55667, NIH-NIA AG039094 (to J.C.R.); NIH-ES 011985-02 (to D.W.W.) and UCD-UCLA CNR pilot grant (to K.G.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Triglycerides as vascular risk factors: new epidemiologic insights. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2009;24(4):345–350. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32832c1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norata GD, Grigore L, Raselli S, Seccomandi PM, Hamsten A, Maggi FM, Eriksson P, Catapano AL. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins from hypertriglyceridemic subjects induce a pro-inflammatory response in the endothelium: Molecular mechanisms and gene expression studies. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2006;40(4):484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norata GD, Grigore L, Raselli S, Redaelli L, Hamsten A, Maggi F, Eriksson P, Catapano AL. Post-prandial endothelial dysfunction in hypertriglyceridemic subjects: molecular mechanisms and gene expression studies. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193(2):321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ting HJ, Stice JP, Schaff UY, Hui DY, Rutledge JC, Knowlton AA, Passerini AG, Simon SI. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins prime aortic endothelium for an enhanced inflammatory response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circulation research. 2007;100(3):381–390. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258023.76515.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L, Gill R, Pedersen TL, Higgins LJ, Newman JW, Rutledge JC. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipolysis releases neutral and oxidized FFAs that induce endothelial cell inflammation. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(2):204–213. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700505-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutledge JC, Mullick AE, Gardner G, Goldberg IJ. Direct visualization of lipid deposition and reverse lipid transport in a perfused artery: roles of VLDL and HDL. Circ Res. 2000;86(7):768–773. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eiselein L, Wilson DW, Lame MW, Rutledge JC. Lipolysis products from triglyceride-rich lipoproteins increase endothelial permeability, perturb zonula occludens-1 and F-actin, and induce apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(6):H2745–2753. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00686.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Sapuri-Butti AR, Aung HH, Parikh AN, Rutledge JC. Triglyceride-Rich Lipoprotein Lipolysis Increases Aggregation of Endothelial Cell Membrane Microdomains and Produces Reactive Oxygen Species. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01366.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe T, Oue N, Yasui W, Ryoji M. Rapid and preferential induction of ATF3 transcription in response to low doses of UVA light. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310(4):1168–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Criswell T, Leskov K, Miyamoto S, Luo G, Boothman DA. Transcription factors activated in mammalian cells after clinically relevant doses of ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22(37):5813–5827. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Zama T, Kamimoto T, Aoki R, Ikeda Y, Kimura H, Hagiwara M. TNFalpha-induced ATF3 expression is bidirectionally regulated by the JNK and ERK pathways in vascular endothelial cells. Genes Cells. 2004;9(1):59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill CS, Wynne J, Treisman R. The Rho family GTPases RhoA, Rac1, and CDC42Hs regulate transcriptional activation by SRF. Cell. 1995;81(7):1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coso OA, Chiariello M, Yu JC, Teramoto H, Crespo P, Xu N, Miki T, Gutkind JS. The small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1995;81(7):1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minden A, Lin A, Claret FX, Abo A, Karin M. Selective activation of the JNK signaling cascade and c-Jun transcriptional activity by the small GTPases Rac and Cdc42Hs. Cell. 1995;81(7):1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hai T, Curran T. Cross-family dimerization of transcription factors Fos/Jun and ATF/CREB alters DNA binding specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(9):3720–3724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, Allen AE, Sivaprasad U. ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr. 1999;7(4–6):321–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan Y, Chen H, Siu F, Kilberg MS. Amino acid deprivation and endoplasmic reticulum stress induce expression of multiple activating transcription factor-3 mRNA species that, when overexpressed in HepG2 cells, modulate transcription by the human asparagine synthetase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(40):38402–38412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang HY, Wek SA, McGrath BC, Lu D, Hai T, Harding HP, Wang X, Ron D, Cavener DR, Wek RC. Activating transcription factor 3 is integral to the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 kinase stress response. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(3):1365–1377. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1365-1377.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.den Hartigh LJ, Connolly-Rohrbach JE, Fore S, Huser TR, Rutledge JC. Fatty acids from very low-density lipoprotein lipolysis products induce lipid droplet accumulation in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3927–3936. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson A, Eilers A, Lallemand D, Kyriakis J, Rubin LL, Ham J. Phosphorylation of c-Jun is necessary for apoptosis induced by survival signal withdrawal in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18(2):751–762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00751.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litvak V, Ramsey SA, Rust AG, Zak DE, Kennedy KA, Lampano AE, Nykter M, Shmulevich I, Aderem A. Function of C/EBPdelta in a regulatory circuit that discriminates between transient and persistent TLR4-induced signals. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):437–443. doi: 10.1038/ni.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zmuda EJ, Viapiano M, Grey ST, Hadley G, Garcia-Ocana A, Hai T. Deficiency of Atf3, an adaptive-response gene, protects islets and ameliorates inflammation in a syngeneic mouse transplantation model. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1438–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1696-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khuu CH, Barrozo RM, Hai T, Weinstein SL. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) represses the expression of CCL4 in murine macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2007;44(7):1598–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, Rust AG, Korb M, Roach JC, Kennedy K, Hai T, Bolouri H, Aderem A. Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 2006;441(7090):173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature04768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitmore MM, Iparraguirre A, Kubelka L, Weninger W, Hai T, Williams BR. Negative regulation of TLR-signaling pathways by activating transcription factor-3. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):3622–3630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu JC, Laz T, Mohn KL, Taub R. Identification of LRF-1, a leucine-zipper protein that is rapidly and highly induced in regenerating liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(9):3511–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(8):599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu JC, Bravo R, Taub R. Interactions among LRF-1, JunB, c-Jun, and c-Fos define a regulatory program in the G1 phase of liver regeneration. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(10):4654–4665. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gurzov EN, Ortis F, Bakiri L, Wagner EF, Eizirik DL. JunB Inhibits ER Stress and Apoptosis in Pancreatic Beta Cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao M, Labuda T, Xia Y, Gallagher E, Fang D, Liu YC, Karin M. Jun turnover is controlled through JNK-dependent phosphorylation of the E3 ligase Itch. Science. 2004;306(5694):271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1099414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai CY, Huang JF, Hsieh MY, Hou NJ, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Wang LY, Chang WY, Chuang WL, Yu ML. Insulin resistance predicts response to peginterferon-alpha/ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Hepatol. 2009;50(4):712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bubici CPS, Dean K, Franzoso G. Mutual cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor-kappa B: molecular basis and biological significance. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6731–6748. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Martin R, Hoeth M, Hofer-Warbinek R, Schmid JA. The transcription factor NF-kappa B and the regulation of vascular cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(11):E83–88. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prudovsky I, Tarantini F, Landriscina M, Neivandt D, Soldi R, Kirov A, Small D, Kathir KM, Rajalingam D, Kumar TK. Secretion without Golgi. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(5):1327–1343. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gargalovic PS, Imura M, Zhang B, Gharavi NM, Clark MJ, Pagnon J, Yang WP, He A, Truong A, Patel S, Nelson SF, Horvath S, Berliner JA, Kirchgessner TG, Lusis AJ. Identification of inflammatory gene modules based on variations of human endothelial cell responses to oxidized lipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(34):12741–12746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605457103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gargalovic PS, Gharavi NM, Clark MJ, Pagnon J, Yang WP, He A, Truong A, Baruch-Oren T, Berliner JA, Kirchgessner TG, Lusis AJ. The unfolded protein response is an important regulator of inflammatory genes in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(11):2490–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242903.41158.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): nuclear receptors with functions in the vascular wall. Z Kardiol. 2001;90 (Suppl 3):125–132. doi: 10.1007/s003920170034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang JT, Welch JS, Ricote M, Binder CJ, Willson TM, Kelly C, Witztum JL, Funk CD, Conrad D, Glass CK. Interleukin-4-dependent production of PPAR-gamma ligands in macrophages by 12/15-lipoxygenase. Nature. 1999;400(6742):378–382. doi: 10.1038/22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407(6801):233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nawa T, Nawa MT, Adachi MT, Uchimura I, Shimokawa R, Fujisawa K, Tanaka A, Numano F, Kitajima S. Expression of transcriptional repressor ATF3/LRF1 in human atherosclerosis: colocalization and possible involvement in cell death of vascular endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2002;161(2):281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.