Abstract

During recovery from glycogen-depleting exercise, there is a shift from carbohydrate oxidation to glycogen resynthesis. The activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex may decrease to reduce oxidation of carbohydrates in favor of increasing gluconeogenic recycling of carbohydrate-derived substrates for this process. The precise mechanism behind this has yet to be elucidated; however, research examining mRNA content has suggested that the less-abundant pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 (PDK4) may reduce PDH activation during exercise recovery. To investigate this, skeletal muscle and liver of wild-type (WT) and PDK4-knockout (PDK4-KO) mice were analyzed at rest (Rest), after exercise to exhaustion (Exh), and after 2 h of recovery with ad libitum feeding (Rec). Although there were no differences in exercise tolerance between genotypes, caloric consumption was doubled by PDK4-KO mice during Rec. Because of this, PDK4-KO mice at Rec supercompensated muscle glycogen to 120% of resting stores. Therefore, an extra group of PDK4-KO mice were pair-fed (PF) with WT mice during Rec for comparison. PF mice fully replenished muscle glycogen but recovered only 50% of liver glycogen stores. Concentrations of muscle lactate and alanine were also lower in PF than in WT mice, indicating that this decrease may lead to a potential reduction of recycled gluconeogenic substrates, due to oxidation of their carbohydrate precursors in skeletal muscle, leading to observed reductions in hepatic glucose and glycogen concentrations. Because of the impairments seen in PF PDK4-KO mice, these results suggest a role for PDK4 in regulating the PDH complex in muscle and promoting gluconeogenic precursor recirculation during recovery from exhaustive exercise.

Keywords: glycogen, oxidative metabolism, exercise

since the discovery of enhanced muscle glycogen synthesis following exercise almost 50 years ago (1), multiple mechanisms have been proposed and investigated to characterize this phenomenon. Although the events upstream of glycogen formation (glucose uptake) (7, 26, 27), as well as the fates of gluconeogenic precursors (e.g., lactate and alanine) (2, 3, 29) have been extensively studied, a mechanism for promoting the shift to fat oxidation and recirculation of glucose-derived substrates following exercise has received less attention. As pyruvate is the dominant precursor for lactate and alanine production, as well as carbohydrate oxidation, the chosen fate of this metabolite following exercise could have a heavy influence on whole body carbohydrate metabolism. Pyruvate oxidation is regulated by the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex, which may also play a role in enhancing muscle glycogen resynthesis postexercise. Studies examining changes in fuel selection after exercise in human skeletal muscle have observed decreased PDH activation (PDHa activity) (15, 19) along with increased reliance on fatty acids and concomitant increases in glycogen storage (15). As the activity of the PDH complex is regulated, being stimulated by two PDH phosphatases and depressed by four pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDK1–4), observed reductions in PDHa activity during exercise recovery may be mediated by one of the PDK isoforms.

Although changes in the activity of PDHa during and after exercise have been previously examined in muscle (14, 15, 19, 23–25), the roles of each kinase during and after exercise have only been marginally elucidated because of the challenge of isolating the roles of the individual PDKs. Multiple studies have demonstrated increased PDK4 transcription and mRNA production with exercise (10, 19, 21, 22), suggesting that changes in PDK4 activity may reduce flux through PDH during both exercise and recovery. Investigating this, a recent study by our group observed impaired PDH regulation in PDK4-knockout (PDK4-KO) mice with acute muscle contraction ex vivo, supporting the involvement of PDK4 during exercise (9). As PDK4 transcription is markedly elevated postexercise, it is likely that PDK4 may also regulate the PDH complex in the period following exhaustive exercise and that this may enhance glycogen resynthesis. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the role of PDK4 in promoting glycogen resynthesis during recovery from exhaustive exercise in skeletal muscle of wild-type (WT) and PDK4-KO mice. Considering that both muscle and hepatic glycogen stores are reduced with exercise and that hepatic gluconeogenesis plays a prominent role following exercise, we also examined the role of PDK4 in resynthesis of glycogen in the liver. We hypothesized that the absence of PDK4 would lead to a reduced capacity to decrease PDH activity during recovery and, therefore, more carbohydrates would be lost to oxidation, resulting in impaired muscle glycogen synthesis postexercise.

METHODS

Animals.

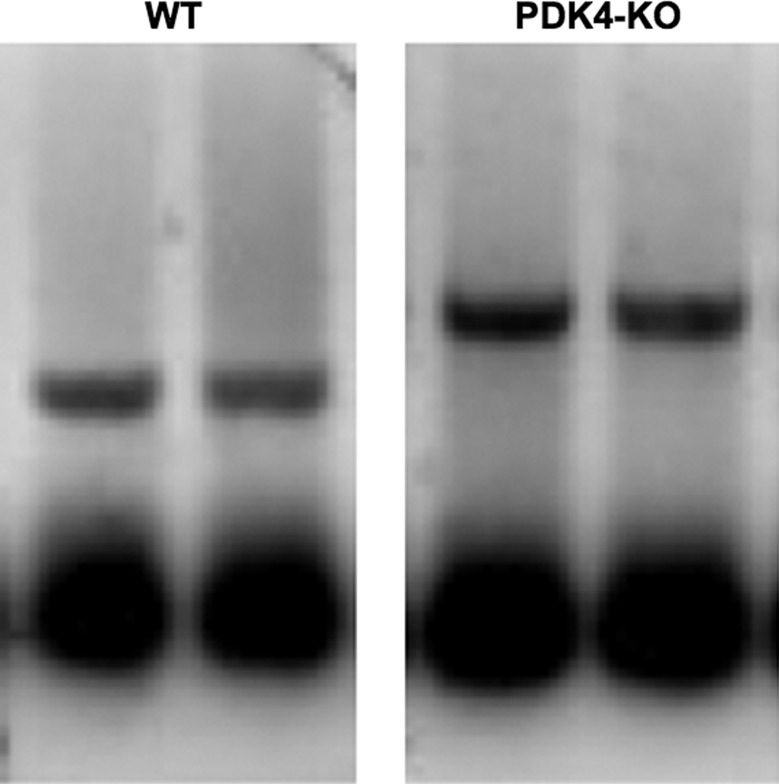

Male PDK4-KO mice were generated from C57BL/6J mice by methods previously described (13) and were obtained from the colonies of Dr. Robert Harris (Indiana University School of Medicine). Male WT C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, QC) to serve as paired controls. All mice were housed on a 12:12-h reverse light-dark cycle in a controlled environment in the Brock University Animal Care Facility for at least 1 wk prior to experimentation and had ad libitum access to mouse chow (5015, LabDiet, Aberfoyle, ON, Canada) and water before the experiment. This study was approved by the Brock University Animal Care Committee and conformed to the standards of the Canadian Council for Animal Care. The absence of PDK4 in PDK4-KO mice was confirmed by genotyping liver and muscle tissue (Fig. 1) through PCR (Pengfei Wu and Robert Harris), as previously described (13).

Fig. 1.

Representative genotyping for WT (left, lower bands) and PDK4-KO (right, upper bands) as previously described and demonstrated by Jeoung et al. (13).

Experimental protocol.

Mice were provided a running wheel 1 wk prior to the day of the experiment to allow for familiarization with running. Each genotype was paired, age (∼16 wk) and weight matched (27 ± 2 g and 27 ± 3 g for WT and PDK4-KO, respectively), and separated into three groups consisting of a resting condition, and two exercise conditions. Exercising mice were brought to a dark room and placed on a treadmill (EXER 3/6; Columbus Instruments International, Columbus, OH) for 5 min to allow for familiarization with the treadmill environment. The exercise protocol used was adapted from a protocol previously shown to reduce muscle glycogen stores (20). Mice began running on a 20° incline at an initial speed of 12 m/min with speed increases of 1 m/min after 2 min, 5 min, 10 min, and every additional 10 min of exercise until exhaustion. Exhaustion was determined by an inability to remain halfway up the treadmill before falling off the moving belt four times consecutively despite being encouraged through prodding and puffs of air. Resting (Rest) mice (n = 6) received no special intervention before surgery, and exercising mice were killed either at exercise exhaustion (Exh) (n = 8) or after 2 h of recovery (Rec) with ad libitum feeding (n = 8), with postexercise food and water intake recorded. As the transformation of PDHa activity occurs rapidly, often on the order of seconds, PDHa activity could not be determined. This timeframe, however, did not appear to affect other measurements. As differences in postexercise nutrition between WT and PDK4-KO mice were observed during the 2-h recovery period (Table 1), a group of pair-fed (PF) PDK4-KO mice (n = 8) was included for analysis with food rations weighed out to match average WT food intake. All mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of diluted pentobarbital sodium (6 mg/100 g body wt) and blood glucose (Freestyle, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and lactate (prolactate test meter, Arkray, Kyoto, Japan) concentrations were sampled from the heart using hand-held devices. Hindlimb muscle and liver were immediately harvested and instantly freeze-clamped for further analysis.

Table 1.

Postexercise nutritional intake

| H2O, ml | Food, g | Total kcal | Carb, kcal | Fat, kcal | Pro, kcal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 2.44 ± 0.36 | 0.55 ± 0.09 | 2.57 ± 0.41 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 |

| PDK4-KO | 3.47 ± 0.68 | 1.01 ± 0.10* | 4.71 ± 0.48* | 0.55 ± 0.06* | 0.25 ± 0.03* | 0.20 ± 0.02* |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Feeding and nutritional composition during exercise recovery in wild-type (WT) and PDK4-knockout (PDK4-KO) mice (n = 8). Pair-fed (PF) values are equal to those of WT animals and were fed 0.55 g of chow.

Signficantly different from WT, P < 0.05.

Glycogen and metabolite concentrations.

Whole hindlimb muscle and liver were lyophilized, dissected free of connective tissue, and aliquoted for analysis of glycogen and metabolite concentrations. Glycogen aliquots were acidified in 2 N HCl, heated at 100°C for 2-h, rehydrated, and neutralized in 2 N NaOH. Metabolite aliquots were extracted in 0.5 M HClO4 and neutralized with 2.3 M KHCO3. The concentrations of glycogen, glycogen precursors [glucose and glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P)], and gluconeogenic precursors (lactate and alanine) were analyzed in triplicate using fluorometric techniques, as previously described (8) and modified (6).

Statistics.

A Student's t-test was used to analyze differences between genotypes in time to exhaustion, postexercise nutritional intake, and protein content. A two-way ANOVA [genotype × condition (Rest, Exh, Rec)] was used to examine differences among conditions between WT and PDK4-KO mice in glycogen content and metabolite concentrations. Because PF PDK4-KO mice were only sampled at Rec, a one-way ANOVA was used to examine differences between groups (WT, PDK4-KO, PF PDK4-KO) at Rec for glycogen content and metabolite concentrations. A Tukey's post hoc test was performed when significance was detected (P < 0.05). Because of low concentrations of muscle lactate and G-6-P in the PF group, some samples were not detectable, and these groups did not meet the assumptions of normality and equal variances. Therefore, a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on ranks with a Dunn post hoc test was used to examine differences in muscle lactate and G-6-P concentrations at Rec between WT, PDK4-KO, and PF mice. All values are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Exercise and caloric intake during recovery.

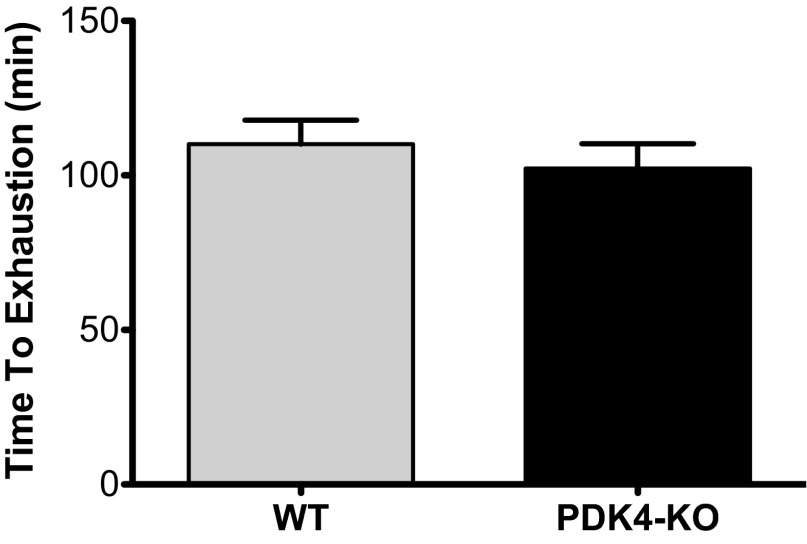

The absence of PDK4 had no effect on running time to exhaustion (P = 0.898) (Fig. 2). In the 2-h period following recovery, a twofold difference in food consumption was observed in PDK4-KO mice relative to WT (P = 0.005) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Running time to exhaustion in wild-type (WT) (n = 16) and PDK4 knockout (PDK4-KO) mice (n = 16). Values are expressed as means ± SE.

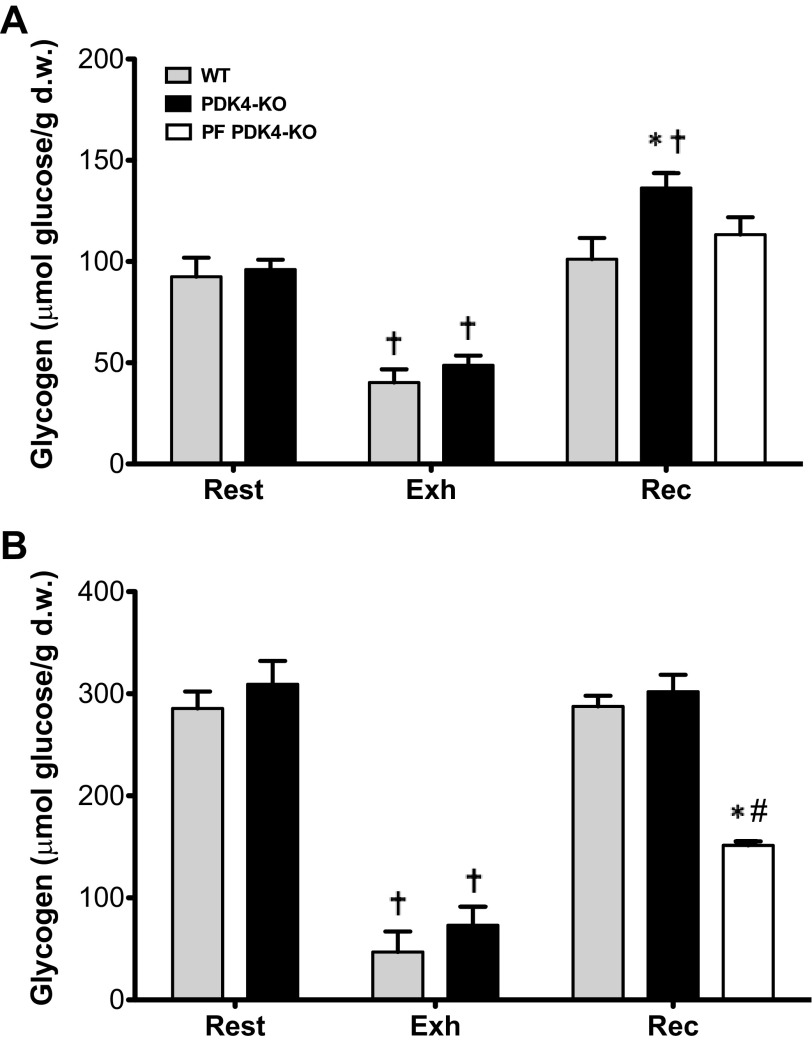

Glycogen concentrations.

Muscle glycogen decreased at Exh to 42% of resting concentrations in WT mice (P < 0.001) and 51% in PDK4-KO mice (P < 0.001), with no significant differences between genotypes. At Rec, muscle glycogen restored to resting levels in WT mice and PF PDK4-KO mice, and supercompensated in PDK4-KO mice an additional 19% over resting levels (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Liver glycogen concentrations at Exh were decreased to 16% of initial resting values in WT mice (P < 0.001) and 24% in PDK4-KO mice (P < 0.001), with no differences between genotypes. Liver glycogen was replenished at Rec to resting levels in WT and PDK4-KO mice, yet remained at only 49% of resting levels in PF PDK4-KO mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Glycogen concentrations in muscle (A) and liver (B) at rest (n = 6), exhaustion (Exh) (n = 8), and recovery (Rec) from exercise (n = 8). WT, wild-type; PDK4-KO, PDK4-knockout; PF, pair fed PDK4-KO. Values are presented as means ± SE. †Significantly different than rest within a genotype, P < 0.05. *Different than WT for a given time-point, P < 0.05. #Significantly different than Rec PDK4-KO, P < 0.05.

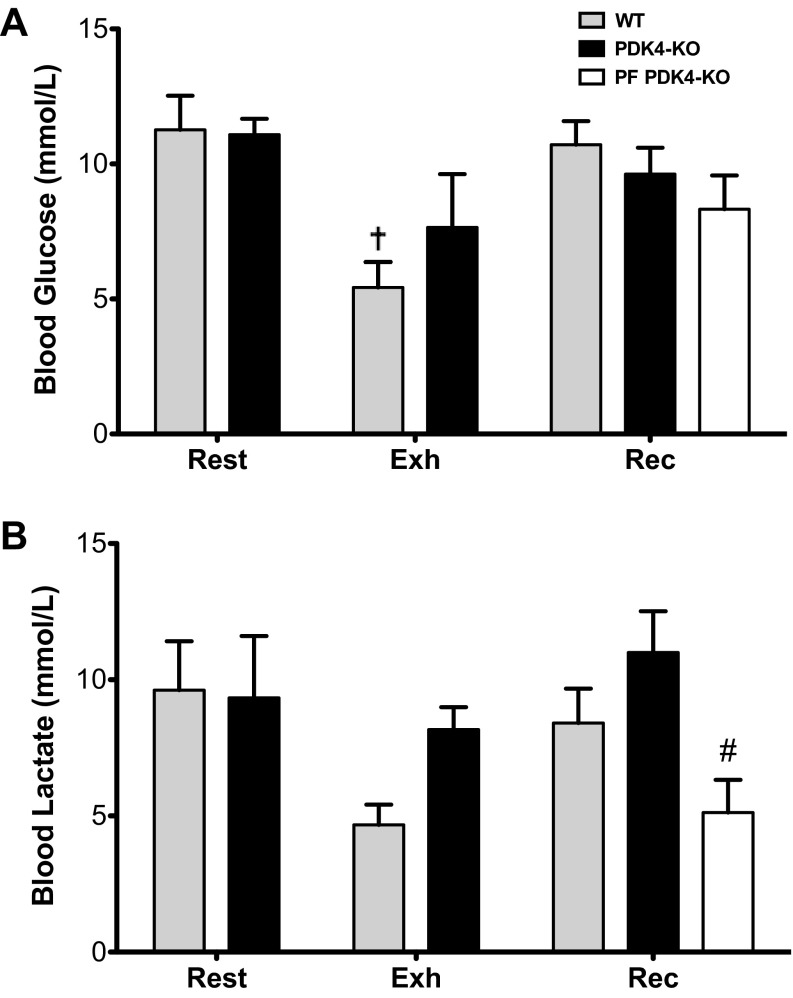

Metabolite concentrations.

Blood glucose was significantly lower in WT mice at Exh only, with no differences among groups at Rec (Fig. 4). Blood lactate at Rec was significantly lower in PF PDK4-KO mice than WT and PDK4-KO mice, with no differences between genotypes at other time points (Fig. 4). No differences were detected in muscle glucose concentrations between groups; however, lactate and alanine concentrations in muscle were significantly lower in the PF PDK4-KO group compared with Rec WT and PDK4-KO mice (Table 2). In the liver, glucose concentrations decreased as a result of exercise in WT (P < 0.001) and PDK4-KO mice (P = 0.043), while after recovery, glucose returned to resting values in PDK4-KO mice, recovered to ∼65% of rest in WT mice, and remained low in PF PDK4-KO mice (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Blood glucose (A) and lactate concentrations (B) at rest (n = 6), exhaustion (Exh) (n = 8) and recovery (Rec) (n = 8). WT, wild-type; PDK4-KO, PDK4-knockout; PF, pair fed PDK4-KO. Values are expressed as means ± SE. †Significantly different than rest within a genotype, P < 0.05. #Significantly different than Rec PDK4-KO, P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Muscle metabolites

| Rest |

Exh |

Rec |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | PDK4-KO | WT | PDK4-KO | WT | PDK4-KO | PF | |

| Muscle | |||||||

| Glucose | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| G-6-P | 8.1 ± 3.0 | 8.2 ± 2.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7† | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 8.5 ± 2.7 | 7.9 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

| Lactate | 23.0 ± 8.6 | 9.8 ± 4.5 | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 8.5 ± 1.1 | 16.8 ± 5.3 | 14.7 ± 3.7 | 3.7 ± 1.5*# |

| Alanine | 5.4 ± 2.0 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 5.0 ± 2.0 | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 7.0 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 0.8*# |

Values are expressed as μmol/g dry weight ± SE. Muscle metabolite concentrations at rest, (n = 6) exhaustion (Exh) (n = 6), and recovery (Rec) (n = 8) (exceptions: PF lactate, n = 5, and PF G-6-P, n = 6).

WT, wild-type; PDK4-KO, PDK4-knockout; PF, pair fed PDK4-KO.

Signficantly different than rest within a genotype, P < 0.05.

Significantly different than WT for a given time point, P < 0.05.

Signficantly different than Rec PDK4-KO, P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Liver metabolites

| Rest |

Exh |

Rec |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | PDK4-KO | WT | PDK4-KO | WT | PDK4-KO | PF | |

| Liver | |||||||

| Glucose | 86.5 ± 8.8 | 65.3 ± 9.6 | 17.3 ± 0.1† | 34.4 ± 9.2† | 56.0 ± 7.8† | 66.6 ± 7.8 | 27.1 ± 5.1*# |

| G-6-P | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.01 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| Lactate | 31.0 ± 5.0 | 29.9 ± 7.8 | 6.7 ± 3.4† | 8.2 ± 2.8† | 22.1 ± 3.7 | 29.2 ± 3.1 | 19.8 ± 7.9 |

| Alanine | 8.8 ± 3.3 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 11.0 ± 1.5 | 14.9 ± 3.3 | 15.8 ± 8.6 | 12.4 ± 3.7 |

Values are expressed as μmol/g dry weight ± SE. Liver metabolite concentrations at rest (n = 6), exhaustion (Exh) (n = 8), and recovery (Rec) (n = 8).

WT, wild-type; PDK4-KO, PDK4-knockout; PF, pair-fed PDK4-KO.

Different than rest within a genotype, P < 0.05.

Different than WT for a given time-point, P < 0.05.

Different than Rec PDK4-KO, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the involvement of PDK4 in regulating the PDH complex during postexercise glycogen resynthesis and found that 1) PDK4 plays a role during recovery from exhaustive exercise; however, 2) contrary to our hypothesis, the absence of PDK4 does not compromise glycogen resynthesis in skeletal muscle, but 3) causes increased feeding in PDK4-KO mice during recovery, and 4) leads to a decreased availability of gluconeogenic substrates and impaired hepatic glycogen resynthesis in PDK4-KO mice when pair-fed (PF) with WT mice.

In this study, glycogen concentrations in skeletal muscle and liver were successfully reduced at exhaustion and resynthesized during recovery in both genotypes fed ad libitum. This observation was contrary to the hypothesis that muscle glycogen utilization would be increased and glycogen synthesis would be impaired in PDK4-KO mice due to increased loss of carbohydrate through PDH. We have previously observed increased PDHa activation during muscle contraction in isolated extensor digitorum longus muscle, and this increased activation would be expected to increase oxidative loss of carbohydrate (9). In this study, however, we also observed a twofold greater caloric intake in PDK4-KO mice feeding ad libitum during recovery, and although the mechanism for this is unknown, this potentially indicates compensation for an oxidative loss of carbohydrate. As a result of this increased feeding, muscle glycogen unexpectedly supercompensated by an additional ∼20% over resting concentrations. To further investigate this discrepancy, a group of PDK4-KO mice was pair-fed (PF PDK4-KO group) 0.55 g of chow as consumed by WT mice during recovery, and in these mice, skeletal muscle glycogen recovered to resting levels. These observations strongly support that PDK4 is not required for postexercise glycogen resynthesis in skeletal muscle.

Although liver glycogen resynthesized to the same degree in recovered WT and PDK4-KO mice, PF PDK4-KO mice demonstrated impaired liver glycogen resynthesis in spite of fully restored muscle glycogen levels. This observation suggests preferential resynthesis of muscle glycogen when caloric availability was limited to levels consumed by WT controls during recovery and is supported by previous studies showing complete muscle glycogen resynthesis but impaired hepatic glycogen levels in both rodents and humans with fasting following exercise (5, 16). Although blood glucose concentrations were maintained in all groups during recovery, intracellular liver glucose concentrations were significantly lower in PF PDK4-KO compared with recovered WT and PDK4-KO mice. This supports that hepatic glucose output is sufficient for maintenance of blood glucose homeostasis, but also that the abundance of available gluconeogenic substrates were not significant enough to promote both hepatic glucose output and repletion of glycogen stores. The liver has a substantially increased reliance on muscle-released lactate and alanine to support gluconeogenesis during recovery (2, 3, 29, 32, 33), and in this study, the concentrations of both of these substrates were reduced in PF PDK4-KO muscle with concomitant decreases in circulating blood lactate concentrations and their conversion to glucose in the liver. As WT and PF PDK4-KO mice differ only in their PDK4 content, these data suggest that the absence of PDK4 during recovery may result in a loss of pyruvate to oxidation in muscle, decreasing the formation of lactate and alanine, and impairing the recirculation of these carbohydrate-derived substrates for gluconeogenesis. The role of PDK4 in promoting recycling of gluconeogenic substrates has been suggested previously (31), and our conclusion is supported by a previous study in which the indiscriminate PDK inhibitor, dichloroacetate, was infused into rodents recovering from exercise, impairing the activity of all PDK isoforms, reducing the concentrations of gluconeogenic precursors in the blood, and impairing hepatic glycogen resynthesis (4).

Finally, although mice in this study were bred in separate facilities, we have demonstrated previously (9) that under resting conditions, mice from both facilities show no differences in body weight, resting metabolite concentrations, or resting PDHa activity in vitro. In addition, WT and PDK4-KO mice in the present study show no differences in age or body weight, exercise time to exhaustion, or in key variables such as glycogen or metabolite concentrations at rest. Although this may not account for all possible variables in genetic drift, the most novel findings of this article are seen when comparing the PDK4-KO mice, pair-fed vs. ad libitum feeding postexercise, demonstrating that our observed phenomenon is due to impaired glucose handling in PDK4-KO mice postexercise as opposed to differences between mice from separate facilities.

Perspectives and Significance

Although the mechanisms regulating the shift from carbohydrate oxidation for use in glycogen resynthesis are unknown, they likely involve altering the activity of the PDH complex. Therefore, we examined the role of PDK4 in regulating the PDH complex during glycogen resynthesis after exhaustive exercise in mice. This study demonstrates that PDK4 is not necessary for resynthesis of skeletal muscle glycogen stores. However, the absence of PDK4 results in potentially impaired oxidative handling of pyruvate in muscle, leading to reduced lactate and alanine production and recirculation when caloric availability is limited, impairing hepatic glucose availability and glycogen resynthesis. These data suggest that the role for PDK4 postexercise is not to aid in enhancing muscle glycogen resynthesis, but to promote the recirculation of gluconeogenic precursors.

It has been previously suggested that inhibition of select PDK isoforms could be a potential drug target for the treatment of diabetes (17, 18, 28, 30), and, indeed, the removal of PDK4 has been shown to increase glucose sensitivity (13) and aid in resistance to the effects of high-fat feeding (11, 12). As drug treatments would ideally act as a transient stepping stones to healthier living and exercise, recent work by our group in incubated muscle (9) suggested that PDK4 inhibition may result in complete activation of the PDH complex during exercise and, therefore, lead to severe exercise intolerance and dangers to glucose homeostasis. The results of the present study, however, show no differences in exercise capacity or glucose homeostasis in exhausted WT and PDK4-KO mice. It is, therefore, plausible that a selective inhibitor of PDK4 either at the protein or transcriptional level has potential applications as a practical target for drug therapy in the diabetic population, although further investigation is required.

GRANTS

This study was supported by operating grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (to S. J. Peter and P. J. LeBlanc), Brock University International Collaborative Funding Initiative (to P. J. LeBlanc), the World Class University program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (to N. H. Jeoung and R. A. Harris), a Merit Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to R. A. Harris) and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012–0002435; to N. H. Jeoung).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: E.A.H., P.J.L., B.D.R., and S.J.P. conception and design of research; E.A.H. and R.E.M. performed experiments; E.A.H. and S.J.P. analyzed data; E.A.H., R.E.M., N.H.J., R.A.H., and S.J.P. interpreted results of experiments; E.A.H. prepared figures; E.A.H. drafted manuscript; E.A.H., R.E.M., P.J.L., B.D.R., N.H.J., R.A.H., and S.J.P. edited and revised manuscript; E.A.H., R.E.M., P.J.L., B.D.R., N.H.J., R.A.H., and S.J.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergström J, Hultman E. Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: an enhancing factor localized to the muscle cells in man. Nature 210: 309–310, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consoli A, Nurjhan N, Reilly JJ, Jr, Bier DM, Gerich JE. Contribution of liver and skeletal muscle to alanine and lactate metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 259: E677–E684, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza HM, Borba-Murad GR, Ceddia RB, Curi R, Vardanega-Peicher M, Bazotte RB. Rat liver responsiveness to gluconeogenic substrates during insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Braz J Med Biol Res 34: 771–777, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favier RJ, Koubi HE, Mayet MH, Sempore B, Simi B, Flandrois R. Effects of gluconeogenic precursor flux alterations on glycogen resynthesis after prolonged exercise. J Appl Physiol 63: 1733–1738, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fell RD, McLane JA, Winder WW, Holloszy JO. Preferential resynthesis of muscle glycogen in fasting rats after exhausting exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 238: R328–R332, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green HJ, Thomson JA, Houston ME. Supramaximal exercise after training-induced hypervolemia. II. Blood/muscle substrates and metabolites. J Appl Physiol 62: 1954–1961, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen PA, Nolte LA, Chen MM, Holloszy JO. Increased GLUT-4 translocation mediates enhanced insulin sensitivity of muscle glucose transport after exercise. J Appl Physiol 85: 1218–1222, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris RC, Hultman E, Nordesjo LO. Glycogen, glycolytic intermediates and high-energy phosphates determined in biopsy samples of musculus quadriceps femoris of man at rest. Methods and variance of values. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 33: 109–120, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst EA, Dunford EC, Harris RA, Vandenboom R, Leblanc PJ, Roy BD, Jeoung NH, Peters SJ. Role of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 in regulating PDH activation during acute muscle contraction. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37: 48–52, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrandt AL, Pilegaard H, Neufer PD. Differential transcriptional activation of select metabolic genes in response to variations in exercise intensity and duration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E1021–E1027, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang B, Jeoung NH, Harris RA. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 4 (PDHK4) deficiency attenuates the long-term negative effects of a high-saturated fat diet. Biochem J 423: 243–252, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeoung NH, Harris RA. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 deficiency lowers blood glucose and improves glucose tolerance in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E46–E54, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeoung NH, Wu PF, Joshi MA, Jaskiewicz J, Bock CB, DePaoli-Roach AA, Harris RA. Role of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 4 (PDHK4) in glucose homoeostasis during starvation. Biochem J 397: 417–425, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiilerich K, Gudmundsson M, Birk JB, Lundby C, Taudorf S, Plomgaard P, Saltin B, Pedersen PA, Wojtaszewski JFP, Pilegaard H. Low muscle glycogen and elevated plasma free fatty acid modify but do not prevent exercise-induced PDH activation in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes 59: 26–32, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimber NE, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL, Dyck DJ. Skeletal muscle fat and carbohydrate metabolism during recovery from glycogen-depleting exercise in humans. J Physiol 548: 919–927, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maehlum S, Felig P, Wahren J. Splanchnic glucose and muscle glycogen metabolism after glucose feeding during postexercise recovery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab Gastrointest Physiol 235: E255–E260, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayers RM, Leighton B, Kilgour E. PDH kinase inhibitors: a novel therapy for type II diabetes? Biochem Soc Trans 33: 367–370, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrell JA, Orme J, Butlin RJ, Roche TE, Mayers RM, Kilgour E. AZD7545 is a selective inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 1168–1170, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mourtzakis M, Saltin B, Graham T, Pilegaard H. Carbohydrate metabolism during prolonged exercise and recovery: interactions between pyruvate dehydrogenase, fatty acids, and amino acids. J Appl Physiol 100: 1822–1830, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pederson BA, Cope CR, Schroeder JM, Smith MW, Irimia JM, Thurberg BL, DePaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ. Exercise capacity of mice genetically lacking muscle glycogen synthase: in mice, muscle glycogen is not essential for exercise. J Biol Chem 280: 17260–17265, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilegaard H, Keller C, Steensberg A, Helge JW, Pedersen BK, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Influence of pre-exercise muscle glycogen content on exercise-induced transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes. J Physiol 541: 261–271, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilegaard H, Ordway GA, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression in human skeletal muscle during recovery from exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E806–E814, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putman CT, Jones NL, Hultman E, Hollidge-Horvat MG, Bonen A, McConachie DR, Heigenhauser GJF. Effects of short-term submaximal training in humans on muscle metabolism in exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E132–E139, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putman CT, Jones NL, Lands LC, Bragg TM, Hollidgehorvat MG, Heigenhauser GJF. Skeletal-muscle pyruvate-dehydrogenase activity during maximal exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 269: E458–E468, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putman CT, Spriet LL, Hultman E, Lindinger MI, Lands LC, Mckelvie RS, Cederblad G, Jones NL, Heigenhauser GJF. Pyruvate-dehydrogenase activity and acetyl group accumulation during exercise after different diets. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 265: E752–E760, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter EA, Garetto LP, Goodman MN, Ruderman NB. Enhanced muscle glucose metabolism after exercise: modulation by local factors. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 246: E476–E482, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richter EA, Garetto LP, Goodman MN, Ruderman NB. Muscle glucose metabolism following exercise in the rat: increased sensitivity to insulin. J Clin Invest 69: 785–793, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche TE, Hiromasa Y. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase regulatory mechanisms and inhibition in treating diabetes, heart ischemia, and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 830–849, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross BD, Hems R, Krebs HA. The rate of gluconeogenesis from various precursors in the perfused rat liver. Biochem J 102: 942–951, 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugden MC, Holness MJ. Therapeutic potential of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases in the prevention of hyperglycaemia. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 2: 151–165, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugden MC, Kraus A, Harris RA, Holness MJ. Fibre-type specific modification of the activity and regulation of skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) by prolonged starvation and refeeding is associated with targeted regulation of PDK isoenzyme 4 expression. Biochem J 346: 651–657, 2000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasserman DH, Lacy DB, Green DR, Williams PE, Cherrington AD. Dynamics of hepatic lactate and glucose balances during prolonged exercise and recovery in the dog. J Appl Physiol 63: 2411–2417, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasserman DH, Williams PE, Lacy DB, Green DR, Cherrington AD. Importance of intrahepatic mechanisms to gluconeogenesis from alanine during exercise and recovery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 254: E518–E525, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]