Abstract

Synapses are continuously formed and eliminated throughout life in the mammalian brain, and emerging evidence suggests that this structural plasticity underlies experience-dependent changes of brain functions such as learning and long-term memory formation. However, it is generally difficult to understand how the rewiring of synaptic circuitry observed in vivo eventually relates to changes in animal's behavior. This is because afferent/efferent connections and local synaptic circuitries are very complicated in most brain regions, hence it is largely unclear how sensorimotor information is conveyed, integrated, and processed through a brain region that is imaged. The cerebellar cortex provides a particularly useful model to challenge this problem because of its simple and well-defined synaptic circuitry. However, owing to the technical difficulty of chronic in vivo imaging in the cerebellum, it remains unclear how cerebellar neurons dynamically change their structures over a long period of time. Here, we showed that the commonly used method for neocortical in vivo imaging was not ideal for long-term imaging of cerebellar neurons, but simple optimization of the procedure significantly improved the success rate and the maximum time window of chronic imaging. The optimized method can be used in both neonatal and adult mice and allows time-lapse imaging of cerebellar neurons for more than 5 mo in ∼80% of animals. This method allows vital observation of dynamic cellular processes such as developmental refinement of synaptic circuitry as well as long-term changes of neuronal structures in adult cerebellum under longitudinal behavioral manipulations.

Keywords: long-term, time-lapse imaging; two-photon microscopy; development; plasticity

in vivo time-lapse microscopy is now extensively used for imaging fine neuronal structures and activity in the brain of living animals. These experiments have revealed the dynamic nature of synaptic wiring and functional architecture of neuronal ensembles, providing novel insights into experience-dependent changes of brain functions (Bhatt et al. 2009; Chen and Nedivi 2010; Holtmaat and Svoboda 2009; Huber et al. 2012). However, it is generally difficult to understand how the formation and elimination of synapses modify the function of local brain circuitry, and eventually, an animal's behavior.

The cerebellum provides a unique advantage to challenge this problem. Unlike most other brain regions, extensively characterized anatomical and physiological properties of cerebellar neurons provide testable models regarding how sensorimotor information is conveyed and integrated, and how plasticity modifies cerebellar outputs (Linden 2003; Raymond et al. 1996). Furthermore, the developmental rewiring of synaptic circuitry can also be uniquely studied in the cerebellum. Since the massive developmental expansion and reorganization of the cerebellar cortex is mostly postnatal (Altman and Bayer 1996), it is technically possible to image early cortical development in vivo, which is difficult in other brain regions. Despite these advantages, the application of in vivo microscopy has been mostly limited to short-term (approximately several hours) experiments in the cerebellum. To date, only a small number of published studies used chronic (>1 day) time-lapse in vivo imaging (Allegra Mascaro et al. 2013; Carrillo et al. 2013a, b; Kuhn et al. 2012; Nishiyama et al. 2007), and in most of them, maximum duration of the imaging was only 1–2 wk. In our experience, even 1–2 wk of time-lapse imaging had been challenging because the optical clarity of cerebellar cranial windows rapidly decreased in most animals.

There are several excellent articles that describe detailed methods for long-term in vivo imaging of neocortical neurons (Grutzendler et al. 2011; Holtmaat et al. 2009). However, unlike the neocortex, the cerebellum is covered by thick neck muscles. The occipital bone above the cerebellum appears to be highly regenerative, and the surface of the cerebellar cortex is not as flat as that of the neocortex. These factors may contribute to the difficulty of maintaining the optical clarity of a cranial window on the cerebellum, when the method used in the neocortex is directly applied. We therefore refined the methods for cranial window preparation and in vivo microscopy for imaging of cerebellar neurons repeatedly for an extended period of time (many months). By combining these methods with stable neuronal labeling with morphological and functional indicators, long-term reorganization of cerebellar circuitry and functional architecture can be studied during development and adulthood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surgery.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Austin. Since the critical factor for successful long-term in vivo cerebellar imaging is surgical preparation of cranial window, see Carrillo et al. (2013a, b) for methods of neuronal labeling. Male and female C57BL/6 mice and transgenic (tg) mice that express enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) under the control of neurofilament light chain (nefl) promoter (nefl-EGFP tg; Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers, 015882-UCD) were used.

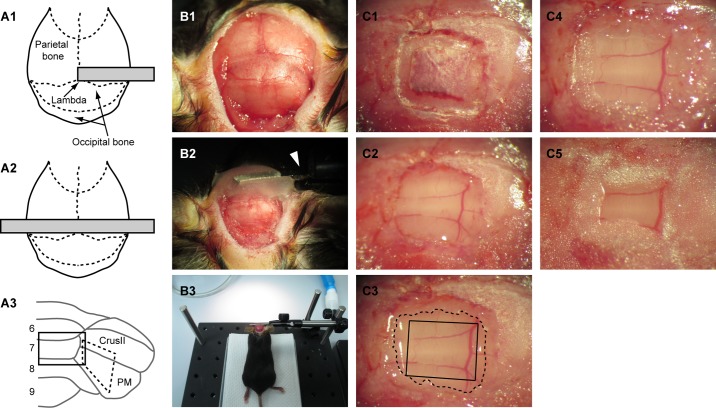

Pups (P5-P8) and adult (≥3 mo old) mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (40/4 and 100/10 mg/kg for pups and adults, respectively). The scalp overlaying skull and neck muscles was removed. Under a surgical microscope, the muscles and fascia overlaying the skull were removed, and the skull surface was cleaned using a sterile cotton applicator (Fig. 1B1). After the skull surface was dried, surgical cyanoacrylate (Vetabond, 3M) was applied on the dried skull, and then a small metal plate was glued to the skull near lambda with dental cement (Ortho-Jet, Lang Dental) as shown in Fig. 1, A1 and B2. For in vivo imaging with anesthetized animals, the minimum size of the plate (∼0.9 mm-thick) is ∼6 × 2 and 12 × 2 mm for pups and adults, respectively. The length of the plate should be longer if imaging is performed with awake, head-fixed animals, because both ends of the plate must be fixed with clamps during imaging (Fig. 1A2). We used a zinc plate (4-hole zinc-plated wire eye strap hanger, #83498, Crown Bolt), which we cut to the appropriate size, but any commercially available metal plate that is not too thick or heavy can be used.

Fig. 1.

Cranial window preparation for long-term in vivo time-lapse imaging of cerebellar neurons. A: the top-down views of mouse skull and approximate size and location of metal plate (gray bar) are shown as schematic drawings (A1 and A2). A short plate is sufficient for imaging an anesthetized mouse (A1), but a longer plate is required for imaging an awake mouse because both ends of the plate must be clamped to securely hold the head under the microscope during image acquisition (A2). The drawing in A3 represents the posterior part of the mouse cerebellum. Lobules 6–9 in the vermis and Crus II and paramedian lobe (PM) in hemisphere are indicated. A rectangle (solid line) and a trapezoid (dashed line) represent exemplar location and size of craniotomy for imaging lobule 7 and PM, respectively. B: surgical preparation for an adult, anesthetized mouse. After neck muscles above the occipital bone are removed and the entire skull surface is cleaned (B1), a small metal plate is attached to the skull with dental cement (B2). The right side of the metal plate is clamped with an MSC-1 miniature slide clamp (arrowhead), and the cutting surface of muscles and scalp are covered by surgical cyanoacrylate in B2. Clamping one end of the plate provides sufficient mechanical stability for surgery. A low-magnification view including our custom surgical stage is shown in B3. C: exemplar images showing the step-by-step procedure of cranial window preparation for imaging lobule 7. First, the occipital bone is thinned with a dental drill as shown in C1, and the island of bone inside of the thinned skull is carefully removed to make a rectangular craniotomy (C2). The dura is left intact. After the bleeding from the bone and/or dura stops, a small, manually cut glass coverslip is placed directly on the dura (C3). It is crucial that the glass coverslip (solid line) locates completely inside of the edge of the craniotomy (dashed line). Then, surgical cyanoacrylate is applied outside of the glass to cover the entire surface of the skull, including the cutting edge of the craniotomy (C4). The small area of the dura (between the solid and dashed lines in C3) is in direct contact with and covered by the surgical cyanoacrylate in this step. Finally, the window is secured by dental cement (C5).

After the plate was attached to the skull, the animal's head was securely held in place by clamping one end of the metal plate to a clamp (MSC-1 miniature slide clamp, Siskiyou) attached to the custom-made surgical stage (Fig. 1, B2 and B3). Surgical cyanoacrylate was applied to the cutting surface of muscles and scalp to prevent bleeding during surgery (Fig. 1B2). A cranial window was then created as described below. The key differences from the conventional method were that 1) the shape of craniotomy was not circular; 2) the size of coverslip must be slightly smaller than the size of craniotomy; and 3) the cutting surface of the bone (i.e., the edge of the craniotomy) must be completely covered by the surgical cyanoacrylate after the cover glass was placed on the cerebellar surface. Because of the surface folding of the cerebellar cortex, the exposed cortical surface was not as flat as that of the neocortex when a circular craniotomy was made. We therefore cut the occipital bone such that the opening would be largely parallel to the longitudinal axis of the folia. A rectangular shaped craniotomy (∼2 × 1.5 mm) was made for imaging vermal lobules, whereas a trapezoid was better suited for hemisphere (Fig. 1A3). To cut the bone in adult mice, a high-speed dental drill (#18000–17, Fine Science Tools) and a small drill bit (tip diameter is 0.5 mm, #19007–05, Fine Science Tools) were used (Fig. 1C1). In pups, a 26-gauge needle was used instead of the dental drill because the occipital bone is very thin and soft (see Fig. 6A). The bone inside of the cut was carefully lifted and removed with forceps to create a craniotomy (Fig. 1C2). The dura was left intact. The degree of bleeding caused by this procedure varied from surgery to surgery. Although it mostly stopped naturally within 10–20 min, a collagen sponge (Aviten Ultraform, Bard) was used to stop bleeding when necessary (Holtmaat et al. 2009).

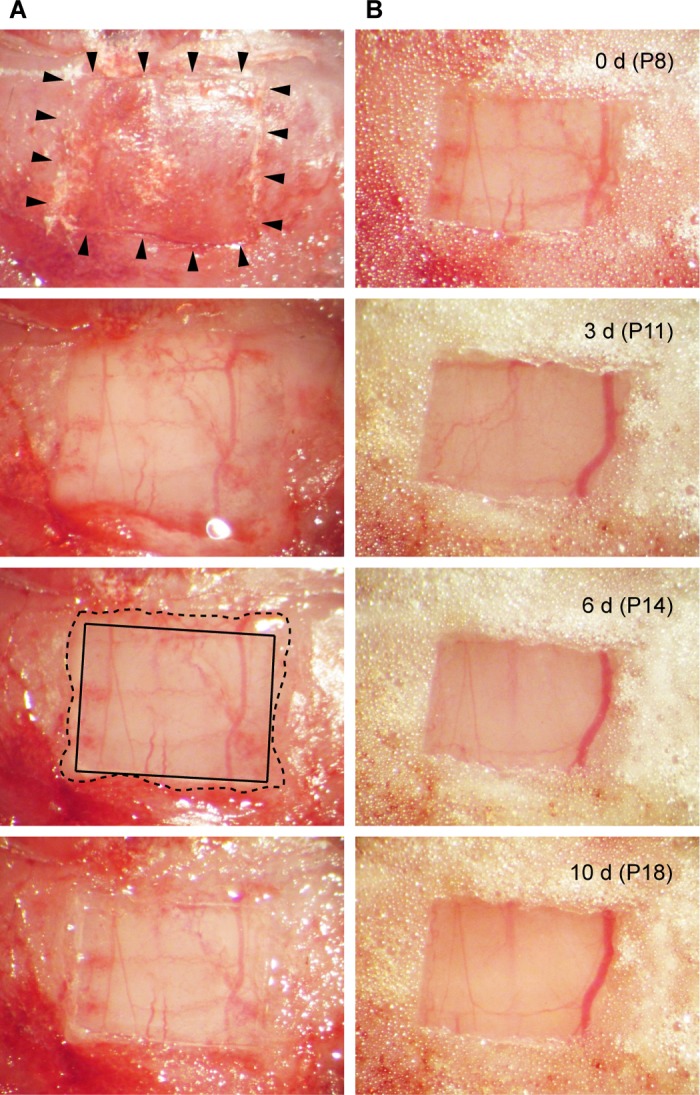

Fig. 6.

Cranial window preparation in a pup. A: the occipital bone of a P8 mouse pup was etched by a 26-gauge needle (arrowheads) to make a rectangular craniotomy (top). After the bone was carefully removed (second from the top), a glass coverslip was placed directly on the dura (second from the bottom). The glass and the edge of the craniotomy were indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Surgical cyanoacrylate was then applied to the outside of the glass (bottom). B: top image shows the window immediately after the dental cement was applied at the final step of surgery. Images of the same widow were taken 3, 6, and 10 days after the surgery.

After bleeding was completely stopped, a drop of physiological saline (0.9% NaCl) was placed on the exposed surface of the cerebellar cortex, and a small coverslip was placed on top. Then, by absorbing the saline with a sterile cotton applicator, the coverslip was placed directly on the dura of the cerebellar surface (Fig. 1C3). To make the small coverslip, we cut a commonly used No. 1 coverslip with a diamond scriber (#52865-005, Andwin Scientific) so that the shape and size of the coverslip would fit to our craniotomy. It is crucial that the size of the coverslip is slightly smaller than the craniotomy (Fig. 1C3). No cutting surface of the bone should be under the coverslip.

After placing the coverslip, we waited for a few minutes to make sure that no bleeding occurred under the coverslip and that the bone was dry. Then, the surgical cyanoacrylate was applied to the edge of the craniotomy to avoid bone regeneration (Fig. 1C4). Dental cement was then applied around the coverslip and on the exposed skull surface to create a cranial window (Fig. 1C5). Isoflurane (0.5–1.5%) was given if additional anesthesia was necessary. The animal was then allowed to recover from the anesthesia and returned to the home cage. As an analgesic, carprofen (5 mg/kg) was administrated daily for 2 days following the surgery. Physiological saline was used to dilute carprofen for adults, but electrolyte solution (Pedialyte, Abbott) was used for pups to minimize the risk of potential dehydration.

Additional care was taken for pups. First, we used a maximum of two pups per litter because we had an impression that surgeries of more than two pups were accompanied by higher incidence of cannibalism by their mothers. Second, when we performed the surgery, we first took the whole litter from the nest, performed the surgery with one or two pups, allowed them to recover with their litter (without the mother) until they were able to move around, and then returned the whole litter to the mother. A previous study showed that this procedure improved the survival rate of pups after surgery (Bower and Waddington 1981). It should be noted, however, that ∼30–40% of mothers still killed or neglected pups after our surgery despite the efforts mentioned above (Carrillo et al. 2013b).

In vivo imaging.

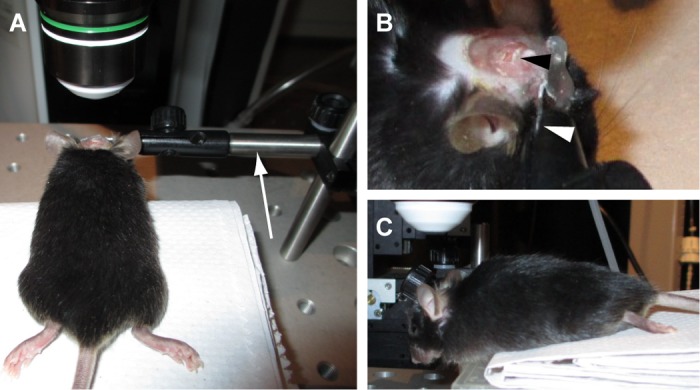

After at least 3 days (pups) or 2 wk (adults) of recovery from the cranial window preparation, the animals were anesthetized with 1–1.5% isoflurane or ketamine/xylazine (30/3 and 50/5 mg/kg for pups and adults, respectively). The animals' heads were securely held in place under a microscope as shown in Fig. 2 by clamping one end of the metal plate to an MSC-1 miniature slide clamp (the same method as shown in Fig. 1B2 and 1B3). One technical consideration for cerebellar in vivo imaging is that, unless the angle of objective lens can be altered, the animals' heads must be significantly tilted such that their nose points almost straight down (Fig. 2C). To prevent a potential difficulty of breathing by this posture, the lower part of the animals' body was slightly raised to minimize the angle of neck bending (Fig. 2C). In our experience, this helps to reduce the occurrence of occasional deep breathing, which causes big brain movement.

Fig. 2.

Head fixation for in vivo imaging. A: an adult, anesthetized mouse is securely held on our custom microscope stage, which is similar to the surgical stage shown in Fig. 1B3. The clamp (arrow) is rotated so that the cranial window and the objective lens become parallel as much as possible. B: a high-magnification image of the clamp and head of the mouse, viewed from the right side of A. The metal plate attached to the skull is clamped as indicated (white arrowhead). A black arrowhead indicates the cranial window. C: the left side view of the mouse. As shown in this image, the nose must be almost pointing down to observe the posterior part of cerebellum unless the angle of the objective lens can be altered.

In vivo two-photon microscopy was performed as described previously using a laser scanning confocal microscope (FV1000MPE, Olympus) equipped with a ×25 water-immersion objective lens (1.05 NA, Olympus XLPlanN) and external, non-descanned photomultiplier tubes (Carrillo et al. 2013a, b). Pulsed infrared laser for two-photon excitation was provided by Mai Tai HP DeepSee mode-locked Ti: sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics).

Microglia labeling.

Microglial labeling was used to probe for inflammatory reactions to cranial window creation. One or two weeks after the cranial window preparation, mice were perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Coronal slices (30 μm thick) of the cerebellum were immunostained with rabbit polyclonal antibody against ionizing calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba 1), a marker protein for microglia (1:1,000; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). The primary antibody was detected by Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:1,000; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The confocal image stacks (spaced 2 μm apart), covering entire slice thickness, were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal microscope with single-photon excitation.

RESULTS

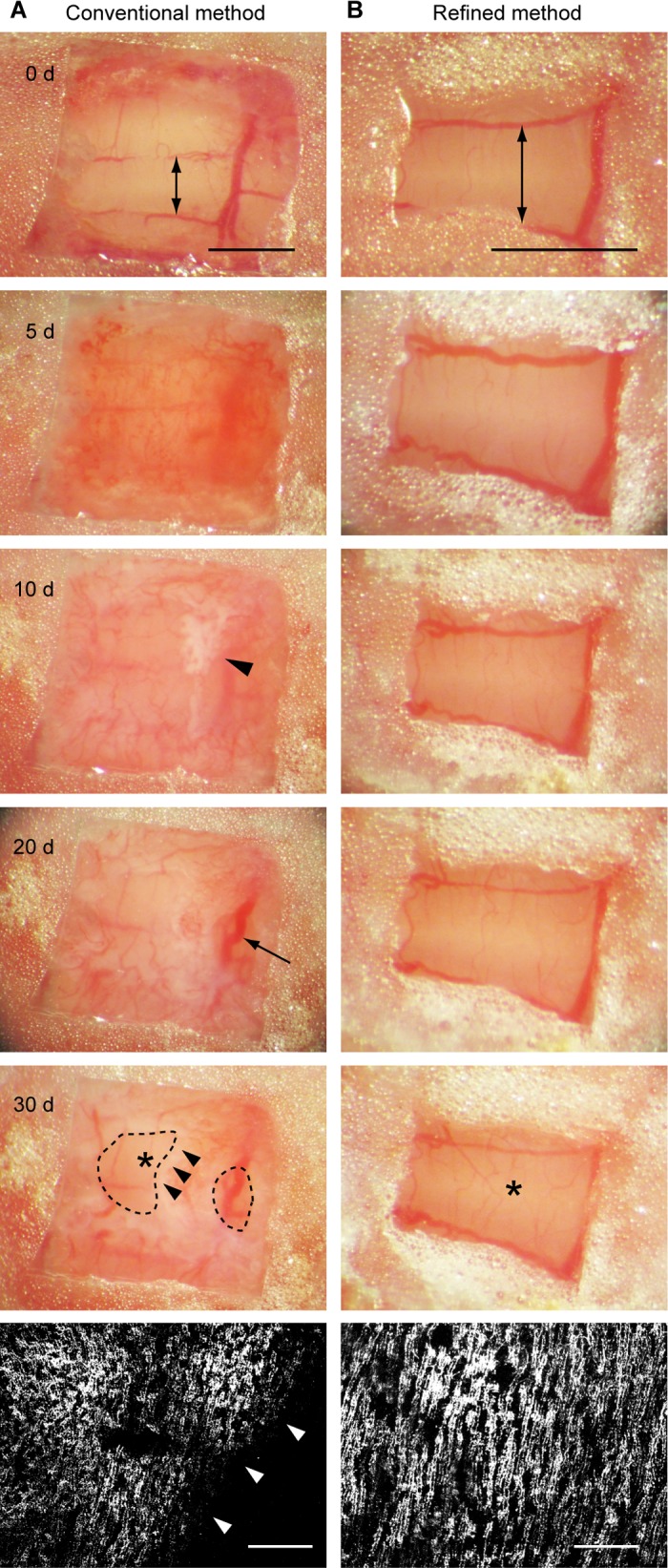

To perform long-term in vivo time-lapse microscopy, the optical clarity of a cranial window must be maintained for a long period of time. However, when we applied the commonly used method for neocortical in vivo imaging to the cerebellum, optical clarity of the window was significantly reduced mostly within a few weeks after the surgery because of bone regeneration and accumulation of white, non-transparent connective tissues (Fig. 3A). The bone began to regenerate within 2 wk after the surgery and continued growing afterward in all animals. The rate of bone regrowth varied from animal to animal, but most windows became unimageable within 4 wk after the surgery. In rare instances, windows retained small imageable areas (i.e., the area that was not yet covered by the growing bone) at 1 mo after the surgery (Fig. 3A), but even such windows were not ideal for reliable long-term imaging. First, time-lapse imaging sessions cannot begin until the imageable area is identified, which is unpredictable during the initial 1–2 wk after the surgery. Therefore, even when optical clarity is maintained for a month in some areas of window, actual time window for data collection is only up to 2–3 wk. Second, it is impossible to predict how the imageable area reduces its size over time. Neurons that are imaged at one time point may be covered by the growing bone by the next imaging session. These problems do not mean that long-term imaging of cerebellar neurons is impossible with the commonly used method. In fact, Kuhn et al. (2012) performed time-lapse vital imaging of cerebellar neurons up to ∼6 wk after the surgery in some preparations. However, in our experience, long-term imaging of cerebellar neurons is difficult with the commonly used method of cranial window preparation, because bone regeneration rapidly occurs after the surgery, and the rate of bone regrowth is not controllable or predictable. We therefore decided to optimize the method of cranial window preparation for the cerebellum.

Fig. 3.

The optical clarity of the entire cranial window is maintained in our preparation. Two methods of cranial window preparation, the conventional method used in the neocortex and our method described here, were compared. The animals used in this figure are transgenic mice that express EGFP in climbing fibers. A: a cranial window was prepared with the conventional method, and images of the same window were taken at 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 days after the surgery. An arrow in the image taken at day 0 indicates lobule 7. The only difference from our method, shown in Fig. 1C, was that a glass coverslip was slightly bigger than the craniotomy. Therefore, the cutting edge of the skull was under the glass, and thus, it was not covered by the cyanoacrylate. Note that the window was already cloudy at day 5. An arrowhead in the image taken at day 10 indicates the initial sign of bone regeneration. A large blood vessel indicated by an arrow in the image taken at day 20 was not a brain surface blood vessel. It was running in growing tissue above the brain surface. At day 30, most of the window was covered by regenerating bone except for 2 small areas enclosed by dashed lines. A 2-photon in vivo image of climbing fibers was taken at day 30 from the area indicated by an asterisk. Maximum projection with top-down view of climbing fibers is shown (bottom). Arrowheads in the bottom 2 images indicate the edge of the growing bone. Note that climbing fibers were visible only within the area that was not yet covered by the bone. B: images of the cranial window shown in Fig. 1C were taken at the same time points as A. As in A, an arrow on the image taken at day 0 indicates lobule 7. Note that images in B have higher magnification than those in A. The window in B was completely transparent throughout the postsurgery period, and no sign of bone regeneration was observed. The surface blood vessels appeared to be dilated at day 5, probably reflecting a transient brain inflammatory response. As in A, 2-photon in vivo image of climbing fibers (bottom) was taken at day 30 from the area indicated by an asterisk. Scale bar, 1 mm and 100 μm for window images and fluorescent images of climbing fibers, respectively.

We thought that the main differences between the neocortex and the cerebellum were flatness of the cortical surface and the skull, the parietal bone above the neocortex and the occipital bone above the cerebellum. Therefore, we modified the size and shape of the craniotomy to minimize the gap between coverslip and cortical surface. To minimize a potential difference between the parietal and occipital bones, we applied surgical cyanoacrylate to the entire surface of the occipital bone, including the edges of the craniotomy (Fig. 1 and 3B). Although the size of imageable brain area was reduced by these modifications, the optical clarity of the window was maintained for a long time in all of our surgeries (Fig. 3B). Among 26 mice that we recently created windows with this method, only six mice showed bone regeneration within 5 mo after the surgery (no mouse within 2 mo, 2 mice between 2 and 3 mo, 2 mice between 3 and 4 mo, and 2 mice between 4 and 5 mo). Approximately 80% of animals (20/26) maintained entirely clear windows for more than 5 mo. Although we did not follow all the animals after 5 mo, nearly 1 year of time-lapse imaging was possible in some of them. These results indicate that, in the cerebellum, the success rate and the maximum time window of long-term in vivo time-lapse imaging can be drastically improved by covering the cutting surface of the occipital bone with surgical cyanoacrylate.

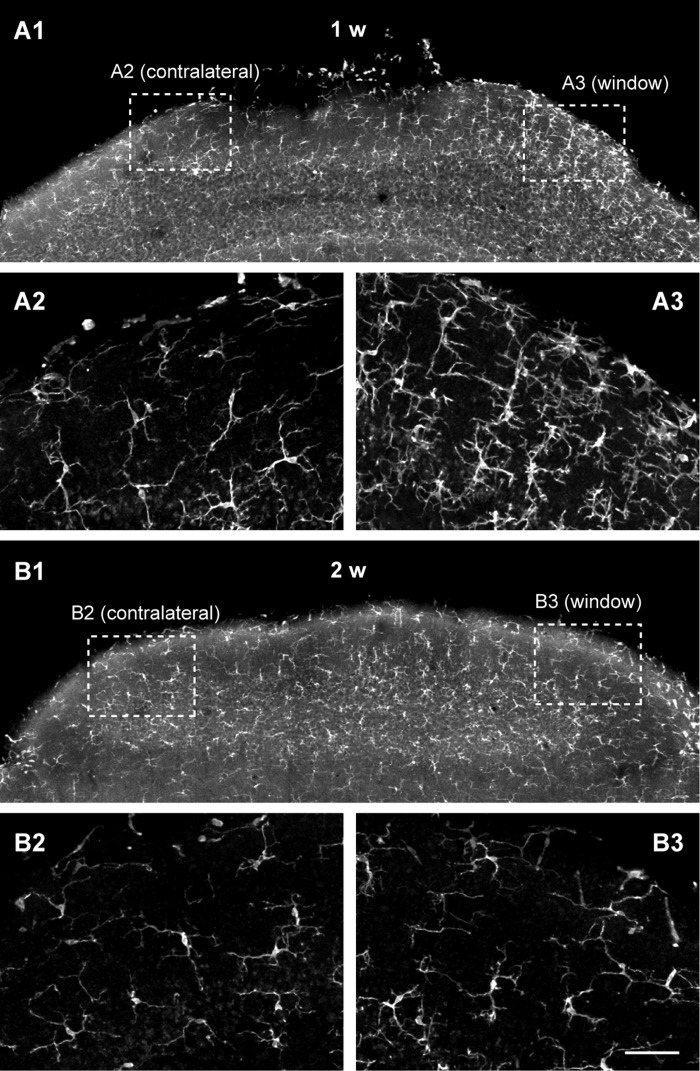

One concern of this procedure was that a small area of dura outside of the coverslip directly contacted the surgical cyanoacrylate. Although previous studies show that cranial window preparation induces negligible or transient brain inflammation, the dura was not in contact with cyanoacrylate (Allegra Mascaro et al. 2013; Holtmaat et al. 2009; Nishiyama et al. 2007). To examine the extent of brain inflammation in our surgery, we examined microglial activation under the cranial window by staining the fixed cerebellar tissues with the anti-ionizing calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba 1) antibody (Ito et al. 1998). At 1 wk after the window preparation (n = 3 mice), a sign of brain inflammation was observed in all animals. In one animal, many activated microglia with short and thick processes (Soltys et al. 2001) were found under the window (data not shown), while in the other two animals, the number of microglia with thin extended process (morphological characteristics of resting microglia) was clearly higher under the window than that in the contralateral side (Fig. 4A). However, the inflammation appeared to have subsided within the following week. At 2 wk after the window preparation (n = 6 mice), similar numbers of resting microglia were found under the window and in the contralateral side in five animals (Fig. 4B). Although more microglia were still found under the window in one animal (similar to Fig. 4A), these results indicate that our cranial window preparation induced only minor and transient brain inflammation in most cases. A previous study has shown that such a cranial window is not associated with altered neuronal structural plasticity (Holtmaat et al. 2009).

Fig. 4.

Brain inflammation occurs, but it subsides within 2 wk after cranial window preparation. Fixed cerebellar slices derived from mice, 1 wk (A) or 2 wk (B) after cranial window preparation, were immunostained with anti-Iba-1 antibody, a marker for microglia. A1 and B1: a low-magnification coronal view. The window was prepared on the right of this composite picture. A2 and B2: a higher-magnification view of the area (contralateral to the window) outlined by white dashed boxes in A1 and B1. A3 and B3: a higher-magnification view of the area (under the window) outlined by white dashed boxes in A1 and B1. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Using this method of cranial window preparation, we recently published results obtained from long-term in vivo imaging of parallel fiber boutons in adult cerebellum (Carrillo et al. 2013a). Parallel fibers are axons of cerebellar granule cells, and the role of long-term depression at parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses in motor learning has been studied extensively over the past 30 years (Ito 2002; Llinas 2011; Mauk et al. 1998; Schonewille et al. 2011). Our data showed that ∼10% of parallel fiber boutons were formed and eliminated over a period of 2 wk without any sensory or behavioral manipulation (Carrillo et al. 2013a). Furthermore, this structural plasticity of parallel fiber boutons was suppressed by acrobatic motor skill training (Carrillo et al. 2013a), which is known to increase the overall density of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses (Black et al. 1990; Kleim et al. 1998). To our knowledge, this was the first demonstration of repeated vital imaging of cerebellar neurons over several months.

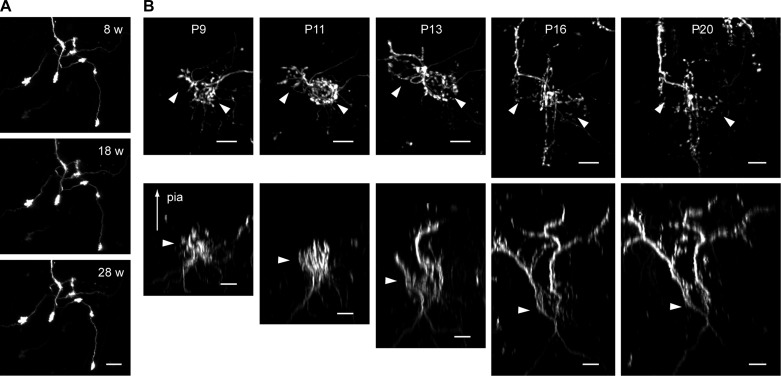

The long-term structural plasticity of other cerebellar neurons can be studied as well by combining our method with virus-mediated expression of fluorescent protein or the use of transgenic mice that express fluorescent protein in a cell type-specific manner. For example, we labeled the subsets of mossy fibers with an adeno-associated virus expressing EGFP (Fig. 5A). Although we originally intended to label climbing fibers by injecting the virus into the inferior olive as described in Nishiyama et al. (2007), a small subset of mossy fibers were occasionally labeled with climbing fibers, probably because of the diffusion of the virus within the tissue. Repeated in vivo time-lapse imaging for more than 6 mo showed remarkable long-term stability of mossy fiber terminals under physiological conditions without any sensory or behavioral manipulation (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Chronic time-lapse in vivo imaging of cerebellar neurons. A: mossy fiber terminals were labeled by adeno-associated virus expressing EGFP, and the same terminals were repeatedly imaged with a 2-photon microscope for ∼6 mo. Images taken at 8, 18, and 28 wk after the surgery are shown. Scale bar, 20 μm. B: developing climbing fibers were labeled by dextran-conjugated tetramethylrhodamine, and structural changes of the same fibers were imaged from postnatal day 9 to 20 (P9-P20). Top panels are maximum projections showing top-down views, whereas bottom panels are 3D reconstructions showing sagittal views of the same fibers shown at top. Arrowheads (top) indicate approximate location of the soma of two adjacent Purkinje cells that are innervated by the labeled climbing fibers. Arrowheads (bottom) indicate approximate location of Purkinje cell layer. Scale bar, 10 μm.

The methods described above are directly applicable to neonatal mice, except that the dose of anesthetics is smaller and a 26-gauge needle is used instead of a dental drill to etch the soft occipital bone (Fig. 6A). Similar to adult animals, the cranial windows in pups are transparent throughout the postsurgery period (Fig. 6B). We labeled a few developing climbing fibers with dextran-conjugated tetramethylrhodamine as described in Carrillo et al. (2013b) and imaged how climbing fibers dynamically changed their structure in vivo during the second and third postnatal weeks (Fig. 5B). At birth, each Purkinje cell is innervated by multiple climbing fibers; an activity-dependent regression of supernumerary climbing fibers ultimately yields a single innervation for most Purkinje cells by the end of the third postnatal week (Crepel et al. 1976; Kano and Hashimoto 2009; Lohof et al. 1996). By combining this in vivo time-lapse imaging with multi-color labeling of climbing fibers, we have recently imaged how multiple climbing fibers compete for the same target Purkinje cell and how the winner emerges through competition (Carrillo et al. 2013b). This study represents the first time-lapse analysis of developmental synapse competition and elimination in the brain of living mammals.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the critical step in surgery for reproducible long-term in vivo imaging of cerebellar neurons is to completely cover the occipital bone, including the cutting surface (i.e., the edge of the craniotomy), with cyanoacrylate. By doing so, optical clarity of the window is maintained for at least 2 mo in all surgeries and for more than 5 mo in ∼80% of the surgeries. This represents significant improvement because, in our experience, it was previously difficult to maintain the clarity of the window on the cerebellum even for a few weeks. It is now possible to easily study long-term structural plasticity of cerebellar neurons during development and long-term behavioral training in adulthood. Furthermore, the method described here might also improve the success rate of open-skull long-term in vivo imaging in brain regions other than the cerebellum.

A thin-skull method, which does not cause even a transient brain inflammation, has been successfully used for long-term in vivo imaging in the neocortex (Grutzendler et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2007). However, it is not suitable in the cerebellum, because 1) the cranial window method provides superior optical clarity than the thin-skull method in the cerebellum (Nishiyama et al. 2007); and 2) repetitive thinning of the occipital bone is extremely difficult probably because the occipital bone is softer and more fragile than the parietal bone. Because of these reasons, we have set aside the thin-skull method and focused on refining the cranial window method.

Not only structural plasticity, but also long-term functional plasticity of cerebellar circuitry can now be studied. Although in vivo microscopy has been used successfully to image activity of cerebellar neurons, previous studies mostly focused on imaging spontaneous or evoked activity within a short time scale. It remains unclear how functional properties of individual cerebellar neurons change over a long period of time. Recently, genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs), GCaMP2, GCaMP3, and D3cpv were successfully used for imaging activities of Purkinje cells, granule cells, and several types of interneurons in vivo (Diez-Garcia et al. 2007; Kuhn et al. 2012; Zariwala et al. 2012). These GECIs have some shortcomings in their sensitivity and kinetics, but improved GECIs, GCaMP6, and Fast-GCaMPs have been developed very recently as ultrasensitive and fast-acting indicators, respectively (Chen et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2013). By combining the use of these new GECIs with our cranial window preparation, long-term time-lapse vital imaging of neuronal activity can be readily performed in the cerebellum.

It should be noted that, if many months of imaging is not necessary, dextran-conjugate chemical fluorescent tracers are also suitable for chronic in vivo imaging (Fig. 5B). Although development of new fluorescent proteins and GECIs has been one of the most fundamental improvements in imaging studies, chemical fluorescent tracers are still useful. Chemical fluorescent tracers have wider variety of color selection, and labeling requires only several hours to 1–2 days. Furthermore, sparse labeling is easily achieved, and some chemical calcium indicators achieve high signal-to-noise ratio with high baseline fluorescence, which are beneficial features for some studies. Nevertheless, use of chemical fluorescent tracers has been limited to conventional histological analyses of fixed tissues or short-term (approximately several hours) live imaging experiments. We have shown here and in our recent study (Carrillo et al. 2013b) that dextran-conjugated fluorescent tracers can be used for chronic in vivo time-lapse imaging for up to 1–2 wk. Thus, they are especially powerful for studying structural and functional changes of neurons within a few weeks during development and short behavioral training in adulthood.

Regarding the potential applications of long-term cerebellar in vivo imaging, we propose several future experiments as examples. First, as shown in Fig. 5A, mossy fiber terminals are very stable over long periods of time without any sensory or behavioral manipulation. However, a recent study shows that fear-inducing stimuli induce the sprouting of filopodia-like protrusions from mossy fiber terminals, which selectively increases their inputs to inhibitory Golgi cells (Ruediger et al. 2011). A similar phenomenon is also observed in mossy fiber terminals in hippocampal CA3 regions (Ruediger et al. 2011). It is therefore expected that imaging this process in vivo under fear conditioning will provide significant insight into the role of mossy fiber sprouting in the acquisition, expression, and/or maintenance of fear memory.

Second, climbing fiber-Purkinje cell system provides an excellent model to study long-term rewiring of synaptic circuitry after neurodegenerative damage. Normally, each Purkinje cell in the mature cerebellar cortex is innervated by a single climbing fiber. When a large population of climbing fibers are damaged and degenerated, surviving fibers sprout new collaterals and innervate nearby denervated Purkinje cells (Rossi et al. 1991). Previous studies suggest that this climbing fiber collateral sprouting can restore a portion of lost motor functions in some cases (Fernandez et al. 1998, 1999; Sherrard and Bower 2003; Willson et al. 2008), but it remains unclear 1) how long collateral sprouting occurs after damage; 2) the extent to which a single survived fiber expands its innervation area; and 3) the relation between the extent of collateral sprouting and behavioral recovery. These questions are efficiently addressed by long-term vital observation of climbing fiber collateral sprouting after damage and combining the imaging with behavioral assessments of motor recovery.

Third, previous in vivo functional imaging has revealed parasagittally oriented functional microbands of Purkinje cells that tend to fire climbing fiber-evoked complex spikes synchronously (Chen et al. 1996; Mukamel et al. 2009; Ozden et al. 2009; Schultz et al. 2009). However, it is unknown whether the structure of this functional microband is static or dynamic over long time scales. By performing long-term in vivo calcium imaging from the population of Purkinje cells labeled by dextran-conjugated calcium indicators or GECIs, we can examine whether the boundaries of the functional microbands dynamically change over time with or without behavioral manipulation. This experiment can also be done by imaging calcium transients in climbing fibers, and it may provide novel insights into the properties of signals conveyed by climbing fibers. For a long time, climbing fiber input to a Purkinje cell was considered to be all-or-none. However, recent studies show that the number of spikes in the brief high-frequency burst of climbing fiber is tightly regulated (Bazzigaluppi et al. 2012; De Gruijl et al. 2012; Maruta et al. 2007; Mathy et al. 2009). These studies suggest that climbing fibers actually convey graded signals by changing the number of spikes in their high-frequency bursts, and such graded signals are proposed to encode more flexible instructive signals for Purkinje cells (Najafi and Medina 2013). Compared with the complex spike-evoked calcium signals in Purkinje cells, the amplitude of calcium transients in climbing fibers is expected to reflect more precisely the number of spikes in each event. Therefore, by combining long-term in vivo calcium imaging of climbing fibers with behavioral manipulation, the roles of climbing fiber bursts in cerebellar function may be investigated.

Fourth, not only developmental synapse competition and elimination, but also other crucial developmental processes can be imaged in the cerebellum. For example, neuronal migration along the radial glial processes is crucial for creating the proper structure of cortical layers, but it completes before birth in neocortex of mice. In the cerebellum, migration of granule cells, from the external to internal granule cell layers, occurs during the first and the second postnatal weeks (Altman and Bayer 1996). It is therefore possible to perform in vivo time-lapse analysis of horizontal and tangential migration of granule cells and investigate how dendrites and parallel fibers are generated after the migration is completed.

One technical concern in performing in vivo imaging during development is that the imaging must begin shortly after the surgery to capture the developmental process of interest. The brain inflammatory response may therefore still be present during the desired period of time-lapse imaging. Despite this shortcoming, in vivo preparations still provide a better experimental system than slice cultures, because synaptic circuitry is intact and the brain inflammatory response is thought to be more severe in slice preparation than in cranial window preparation.

Another limitation of cerebellar in vivo imaging is that it is currently difficult to image individual spines of Purkinje cells. Purkinje cells are the only neurons that send cortical outputs to the deep cerebellar nuclei, and the structural plasticity of Purkinje cell spines has been of great interest (Black et al. 1990; Cesa et al. 2005, 2007; Kleim et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2007, 2013; Sdrulla and Linden 2007; Sugawara et al. 2013). However, because of the small size and high density of spines, single spines are not reliably resolved in vivo even with two-photon microscopy. If superresolution imaging techniques, such as stimulated emission depletion microscopy (Nagerl et al. 2008; Willig et al. 2006), become applicable for in vivo imaging, long-term changes of Purkinje cell spines can be analyzed in living animals.

In conclusion, we have developed a simple, reliable method that allows long-term (weeks to months) in vivo time-lapse imaging of cerebellar neurons in neonatal and adult mice. Our method enables novel experimental approaches to study structural and functional plasticity of cerebellar neurons in vivo during development, behavioral training, and after neurodegenerative injury.

GRANTS

This work was supported by University of Texas at Austin startup funds, Whitehall Foundation, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-073919 (to H. Nishiyama).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.N., J. Colonna, E.S., J. Carrillo, and H.N. performed experiments; N.N., J. Colonna, E.S., J. Carrillo, and H.N. analyzed data; N.N., J. Colonna, J. Carrillo, and H.N. interpreted results of experiments; N.N. and H.N. prepared figures; N.N., J. Colonna, J. Carrillo, and H.N. edited and revised manuscript; N.N., J. Colonna, E.S., J. Carrillo, and H.N. approved final version of manuscript; H.N. conception and design of research; H.N. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Matasha Dhar for comments and Boris Zemelman for providing AAV vector.

REFERENCES

- Allegra Mascaro AL, Cesare P, Sacconi L, Grasselli G, Mandolesi G, Maco B, Knott GW, Huang L, De Paola V, Strata P, Pavone FS. In vivo single branch axotomy induces GAP-43-dependent sprouting and synaptic remodeling in cerebellar cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 10824–10829, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the Cerebellar System: In Relation to its Evolution, Structure, and Functions. Boca Raton: Florida: CRC Press, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Bazzigaluppi P, De Gruijl JR, van der Giessen RS, Khosrovani S, De Zeeuw CI, de Jeu MT. Olivary subthreshold oscillations and burst activity revisited. Front Neural Circ 6: 91, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt DH, Zhang S, Gan WB. Dendritic spine dynamics. Annu Rev Physiol 71: 261–282, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JE, Isaacs KR, Anderson BJ, Alcantara AA, Greenough WT. Learning causes synaptogenesis, whereas motor activity causes angiogenesis, in cerebellar cortex of adult rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 5568–5572, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower AJ, Waddington G. A simple operative technique for chronically severing the cerebellar peduncles in neonatal rats. J Neurosci Methods 4: 181–188, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo J, Cheng SY, Ko KW, Jones TA, Nishiyama H. The long-term structural plasticity of cerebellar parallel fiber axons and its modulation by motor learning. J Neurosci 33: 8301–8307, 2013a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo J, Nishiyama N, Nishiyama H. Dendritic translocation establishes the winner in cerebellar climbing fiber synapse elimination. J Neurosci 33: 7641–7653, 2013b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesa R, Morando L, Strata P. Purkinje cell spinogenesis during architectural rewiring in the mature cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci 22: 579–586, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesa R, Scelfo B, Strata P. Activity-dependent presynaptic and postsynaptic structural plasticity in the mature cerebellum. J Neurosci 27: 4603–4611, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Hanson CL, Ebner TJ. Functional parasagittal compartments in the rat cerebellar cortex: an in vivo optical imaging study using neutral red. J Neurophysiol 76: 4169–4174, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Nedivi E. Neuronal structural remodeling: is it all about access? Curr Opin Neurobiol 20: 557–562, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499: 295–300, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepel F, Mariani J, Delhaye-Bouchaud N. Evidence for a multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the immature rat cerebellum. J Neurobiol 7: 567–578, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gruijl JR, Bazzigaluppi P, de Jeu MT, De Zeeuw CI. Climbing fiber burst size and olivary sub-threshold oscillations in a network setting. PLoS Comput Biol 8: e1002814, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Garcia J, Akemann W, Knopfel T. In vivo calcium imaging from genetically specified target cells in mouse cerebellum. Neuroimage 34: 859–869, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AM, de la Vega AG, Torres-Aleman I. Insulin-like growth factor I restores motor coordination in a rat model of cerebellar ataxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 1253–1258, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AM, Gonzalez de la Vega AG, Planas B, Torres-Aleman I. Neuroprotective actions of peripherally administered insulin-like growth factor I in the injured olivo-cerebellar pathway. Eur J Neurosci 11: 2019–2030, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutzendler J, Yang G, Pan F, Parkhurst CN, Gan WB. Transcranial two-photon imaging of the living mouse brain. Cold Spring Harb Protoc: 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Bonhoeffer T, Chow DK, Chuckowree J, De Paola V, Hofer SB, Hubener M, Keck T, Knott G, Lee WC, Mostany R, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Nedivi E, Portera-Cailliau C, Svoboda K, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L. Long-term, high-resolution imaging in the mouse neocortex through a chronic cranial window. Nat Protoc 4: 1128–1144, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 647–658, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D, Gutnisky DA, Peron S, O'Connor DH, Wiegert JS, Tian L, Oertner TG, Looger LL, Svoboda K. Multiple dynamic representations in the motor cortex during sensorimotor learning. Nature 484: 473–478, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito D, Imai Y, Ohsawa K, Nakajima K, Fukuuchi Y, Kohsaka S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 57: 1–9, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Historical review of the significance of the cerebellum and the role of Purkinje cells in motor learning. Ann NY Acad Sci 978: 273–288, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Hashimoto K. Synapse elimination in the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19: 154–161, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Swain RA, Armstrong KA, Napper RM, Jones TA, Greenough WT. Selective synaptic plasticity within the cerebellar cortex following complex motor skill learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 69: 274–289, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn B, Ozden I, Lampi Y, Hasan MT, Wang SS. An amplified promoter system for targeted expression of calcium indicator proteins in the cerebellar cortex. Front Neural Circ 6: 49, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Jung JG, Arii T, Imoto K, Rhyu IJ. Morphological changes in dendritic spines of Purkinje cells associated with motor learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 88: 445–450, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Park IS, Kim H, Greenough WT, Pak DT, Rhyu IJ. Motor skill training induces coordinated strengthening and weakening between neighboring synapses. J Neurosci 33: 9794–9799, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DJ. Neuroscience. From molecules to memory in the cerebellum. Science 301: 1682–1685, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas RR. Cerebellar motor learning versus cerebellar motor timing: the climbing fibre story. J Physiol 589: 3423–3432, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohof AM, Delhaye-Bouchaud N, Mariani J. Synapse elimination in the central nervous system: functional significance and cellular mechanisms. Rev Neurosci 7: 85–101, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruta J, Hensbroek RA, Simpson JI. Intraburst and interburst signaling by climbing fibers. J Neurosci 27: 11263–11270, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathy A, Ho SS, Davie JT, Duguid IC, Clark BA, Hausser M. Encoding of oscillations by axonal bursts in inferior olive neurons. Neuron 62: 388–399, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauk MD, Garcia KS, Medina JF, Steele PM. Does cerebellar LTD mediate motor learning? Toward a resolution without a smoking gun. Neuron 20: 359–362, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel EA, Nimmerjahn A, Schnitzer MJ. Automated analysis of cellular signals from large-scale calcium imaging data. Neuron 63: 747–760, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagerl UV, Willig KI, Hein B, Hell SW, Bonhoeffer T. Live-cell imaging of dendritic spines by STED microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 18982–18987, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi F, Medina JF. Beyond “all-or-nothing” climbing fibers: graded representation of teaching signals in Purkinje cells. Front Neural Circ 7: 115, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama H, Fukaya M, Watanabe M, Linden DJ. Axonal motility and its modulation by activity are branch-type specific in the intact adult cerebellum. Neuron 56: 472–487, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozden I, Sullivan MR, Lee HM, Wang SS. Reliable coding emerges from coactivation of climbing fibers in microbands of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 29: 10463–10473, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JL, Lisberger SG, Mauk MD. The cerebellum: a neuronal learning machine? Science 272: 1126–1131, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F, Wiklund L, van der Want JJ, Strata P. Reinnervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells by climbing fibres surviving a subtotal lesion of the inferior olive in the adult rat. I. Development of new collateral branches and terminal plexuses. J Comp Neurol 308: 513–535, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruediger S, Vittori C, Bednarek E, Genoud C, Strata P, Sacchetti B, Caroni P. Learning-related feedforward inhibitory connectivity growth required for memory precision. Nature 473: 514–518, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonewille M, Gao Z, Boele HJ, Veloz MF, Amerika WE, Simek AA, De Jeu MT, Steinberg JP, Takamiya K, Hoebeek FE, Linden DJ, Huganir RL, De Zeeuw CI. Reevaluating the role of LTD in cerebellar motor learning. Neuron 70: 43–50, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz SR, Kitamura K, Post-Uiterweer A, Krupic J, Hausser M. Spatial pattern coding of sensory information by climbing fiber-evoked calcium signals in networks of neighboring cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 29: 8005–8015, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sdrulla AD, Linden DJ. Double dissociation between long-term depression and dendritic spine morphology in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Nat Neurosci 10: 546–548, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard RM, Bower AJ. IGF-1 induces neonatal climbing-fibre plasticity in the mature rat cerebellum. Neuroreport 14: 1713–1716, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltys Z, Ziaja M, Pawlinski R, Setkowicz Z, Janeczko K. Morphology of reactive microglia in the injured cerebral cortex. Fractal analysis and complementary quantitative methods. J Neurosci Res 63: 90–97, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara T, Hisatsune C, Le TD, Hashikawa T, Hirono M, Hattori M, Nagao S, Mikoshiba K. Type 1 inositol trisphosphate receptor regulates cerebellar circuits by maintaining the spine morphology of purkinje cells in adult mice. J Neurosci 33: 12186–12196, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XR, Badura A, Pacheco DA, Lynch LA, Schneider ER, Taylor MP, Hogue IB, Enquist LW, Murthy M, Wang SS. Fast GCaMPs for improved tracking of neuronal activity. Nat Commun 4: 2170, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willig KI, Rizzoli SO, Westphal V, Jahn R, Hell SW. STED microscopy reveals that synaptotagmin remains clustered after synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Nature 440: 935–939, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson ML, McElnea C, Mariani J, Lohof AM, Sherrard RM. BDNF increases homotypic olivocerebellar reinnervation and associated fine motor and cognitive skill. Brain 131: 1099–1112, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HT, Pan F, Yang G, Gan WB. Choice of cranial window type for in vivo imaging affects dendritic spine turnover in the cortex. Nat Neurosci 10: 549–551, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zariwala HA, Borghuis BG, Hoogland TM, Madisen L, Tian L, De Zeeuw CI, Zeng H, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Chen TW. A Cre-dependent GCaMP3 reporter mouse for neuronal imaging in vivo. J Neurosci 32: 3131–3141, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]