Abstract

The habenula (Hb) is a small brain structure located in the posterior end of the medial dorsal thalamus and through medial (MHb) and lateral (LHb) Hb connections, it acts as a conduit of information between forebrain and brainstem structures. The role of the Hb in pain processing is well documented in animals and recently also in acute experimental pain in humans. However, its function remains unknown in chronic pain disorders. Here, we investigated Hb resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) compared with healthy controls. Twelve pediatric patients with unilateral lower-extremity CRPS (9 females; 10–17 yr) and 12 age- and sex-matched healthy controls provided informed consent to participate in the study. In healthy controls, Hb functional connections largely overlapped with previously described anatomical connections in cortical, subcortical, and brainstem structures. Compared with controls, patients exhibited an overall Hb rsFC reduction with the rest of the brain and, specifically, with the anterior midcingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, supplementary motor cortex, primary motor cortex, and premotor cortex. Our results suggest that Hb rsFC parallels anatomical Hb connections in the healthy state and that overall Hb rsFC is reduced in patients, particularly connections with forebrain areas. Patients' decreased Hb rsFC to brain regions implicated in motor, affective, cognitive, and pain inhibitory/modulatory processes may contribute to their symptomatology.

Keywords: habenula, resting state, functional connectivity, CRPS, chronic pain, pediatric

the habenula (hb) is a small brain structure located at the posterior end of the medial dorsal thalamus adjacent to the third ventricle. In most vertebrate species, its bilateral nuclei can be divided into medial (MHb) and lateral (LHb) portions (Andres et al. 1999; Díaz et al. 2011) and form together with the pineal gland and posterior commissure the epithalamus (see Fig. 1, A and B). Connectivity and function of the Hb have been reported in animals and humans (Hikosaka 2010; Ide and Li 2011; Beretta et al. 2012; Shelton et al. 2012b). The MHb receives inputs from the septum and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and projects to the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN). The LHb has afferent connections from the lateral hypothalamus, NAc, and caudate/putamen (CPu) and sends projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA), substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), periaqueductal gray (PAG), and dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN). Both MHb and LHb receive input from forebrain regions. Accordingly, this neural network indicates that the Hb may act as a hub between forebrain and midbrain regions, together with its implication in a wide range of behaviors such as sleep-wake cycles, olfaction, ingestion, sexual behavior, stress response, reward-punishment, and pain and analgesia (Thornton et al. 1985; Sugama et al. 2002; Hikosaka 2010). The Hb has also been linked to various psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression (Savitz et al. 2011a, 2011b, 2013), which are commonly comorbid disorders with chronic pain conditions. The role of the Hb in pain processing is well documented in animals (reviewed in Shelton et al. 2012a), as well as in imaging studies of acute experimental pain in humans (Shelton et al. 2012b). Given that chronic pain is associated with profound sensory, emotional, and cognitive changes, the Hb may be implicated in chronification of pain disorders; however, its function in chronic pain disorders remains unknown.

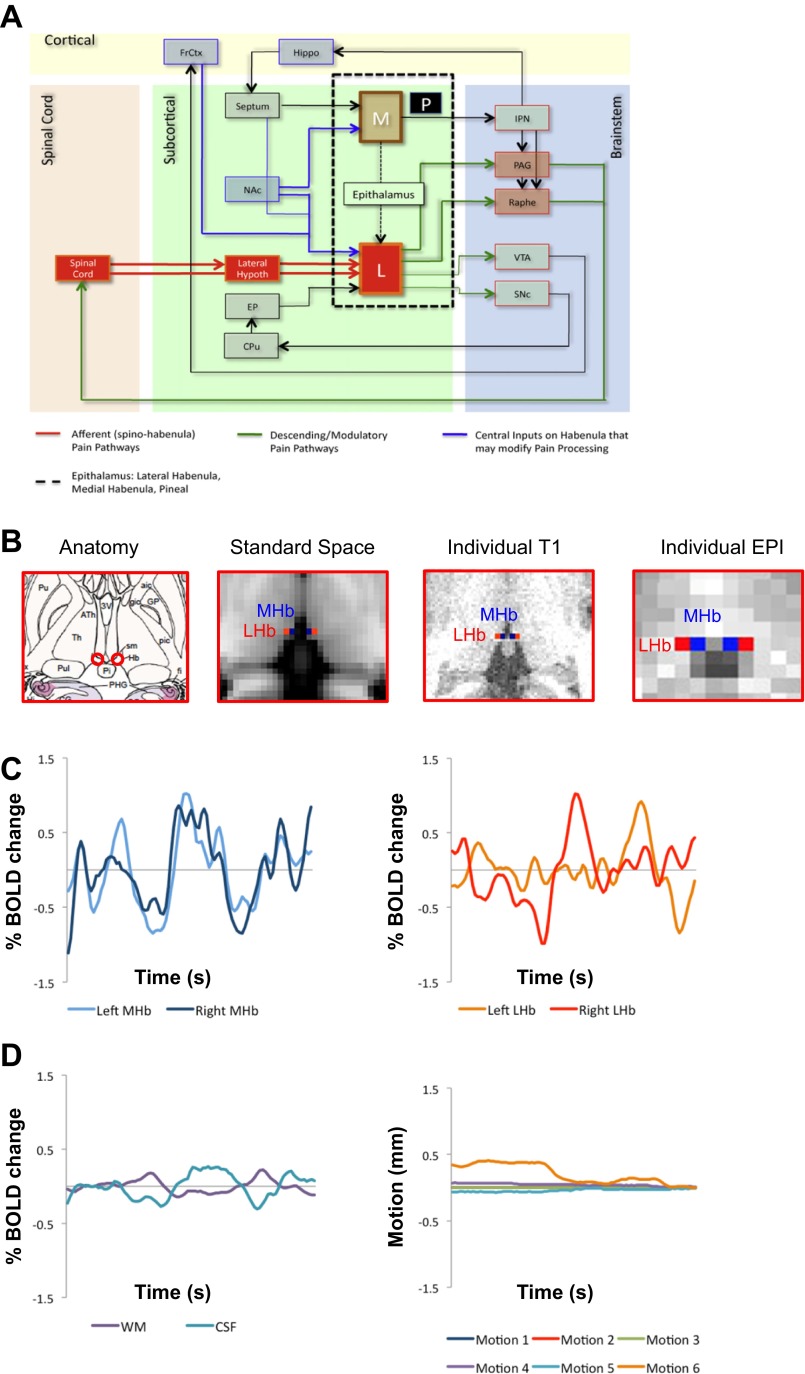

Fig. 1.

Anatomy and resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) of the habenula (Hb). A: Anatomical connectivity of the Hb on the cortical, subcortical, brainstem, and spinal level (from Shelton et al. 2012a and adapted from Bianco and Wilson 2009 with permission). Black dashed rectangle outlines the epithalamus, which contains the lateral (LHb) and medial habenula (mHb) as well as the pineal gland. Red lines represent peripheral afferent connections, green lines show descending and modulatory nociceptive pathways, and blue lines are central inputs to the Hb that may modify pain processing. B: Hb anatomy. From left to right: Hb in atlas image (from Mai et al. 2008 with permission), Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 2-mm standard space, individual anatomical space, and individual echo-planar pulse imaging (EPI) space. The Hb can be easily delineated from surrounding tissue because it appears brighter due to the high amount of Hb of white matter (WM). Boxes of 3 × 3 × 3 voxels were used to define left and right MHb and LHb and then registered to EPI space. Seed registration accuracy was visually inspected and manually adjusted if needed. C: Hb time courses. Left: normalized left (shown in light blue) and right (shown in dark blue) MHb time courses of an individual subject. Right: normalized left (shown in orange) and right (shown in red) LHb time courses of an individual subject. D: individual nuisance variables time courses. Left: normalized WM (shown in purple) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; shown in turquoise) time courses of an individual subject. Right: motion parameters (3 axial and 3 radial motion parameters) resulting from McFLIRT of an individual subject. CPu, caudate/putamen; EP, entopenduncular nucleus; FrCtx, frontal cortex; Hippo, hippocampus; IPN, interpeduncular nucleus; L, lateral habenula; Lateral Hypoth, lateral hypothalamus; M, medial habenula; NAc, nucleus accumbens; P, pineal gland; PAG, periaqueductal gray; Raphe, raphe nuclei; SNc, substantia nigra pars compacta; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic neuropathic pain disorder that is characterized by significant autonomic symptoms and typically occurs in an extremity as a result of acute tissue damage (Bruehl 2010). CRPS manifests itself with typical neuropathic pain symptoms (i.e., spontaneous ongoing pain and abnormally pain responses to innocuous and noxious stimuli), local edema, and autonomic changes (i.e., altered sweating, change in skin color, and temperature in the affected region) (Harden et al. 2013). Additionally, trophic alterations in skin, hair, nails, and motor function may also occur. Experimental studies have repeatedly documented that patients with CRPS exhibit profound alterations in brain function (Fukumoto et al. 1999; Apkarian et al. 2001; Maihöfner et al. 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007; Pleger et al. 2006; Lebel et al. 2008; Becerra et al. 2009; Freund et al. 2010), structure (Geha et al. 2008; Baliki et al. 2011), and chemistry (Fukumoto et al. 1999; Grachev et al. 2000, 2002; Klega et al. 2010). Interestingly, there is growing evidence that chronic pain is also characterized by alterations in resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) as, for example, patients with chronic pain conditions exhibit altered default mode network and attention network rsFC (Baliki et al. 2008; Cauda et al. 2009b, 2010), as well as greater rsFC between pain-related brain regions compared with healthy controls (Cauda et al. 2009a).

Analyzing rsFC has become increasingly popular to investigate intrinsic brain connectivity. Because of the anatomical and functional location of the Hb and its interactions with frontal and brainstem regions and its role in sensory (including pain) and affective processing, we investigated Hb rsFC in patients with CRPS and healthy control subjects. We previously reported structural connectivity in the human Hb based on diffusion tensor imaging (Shelton et al. 2012b). Here, we hypothesized that 1) Hb rsFC parallels Hb anatomical/white matter connectivity, and 2) patients with CRPS exhibit altered Hb rsFC compared with healthy controls. Altered Hb rsFC may provide insights into physiological and behavioral changes due to chronic pain.

METHODS

Subjects

CRPS patients were recruited for this research study that was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children's Hospital. Special study procedures were adopted to accommodate pediatric CRPS patients. Both patient and parent consents were required for study participation. Parents were present during each step of the study. Patients were included in the study if 1) they had refrained from using analgesic medication at least 4 h before the study session, 2) they experienced unilateral lower extremity pain, and 3) their pain intensity was >5 on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS). Exclusion criteria included 1) claustrophobia, 2) significant medical problems (e.g., uncontrollable asthma and seizures, cardiac diseases, psychiatric disorders, and neurological disorders other than CRPS), 3) pregnancy, 4) medical implants and/or devices, and 5) weight >285 lbs, which corresponded to the weight limit of the MRI table. These patients were recruited within a larger study on measures of treatment effects in CRPS (Becerra et al. 2013); here, we limited analyses to Hb rsFC in patients compared with healthy controls before treatment.

MRI Acquisition

Subjects underwent MRI on a 3 T (Siemens Medical, Erlangen, Germany) scanner using a 16-channel head coil. For each participant, we collected a 3D T1-weighted anatomical scan using a magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (128 sagittal slices; TR = 2100 ms; TE = 2.74 ms; TI = 1,100 ms; flip angle = 12°; 1.33 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm voxels).

A resting-state functional (f)MRI scan was acquired using a T2*-weighted echo-planar pulse imaging (EPI) sequence (41 slices; TR = 2.5; TE = 30 ms; 64 × 64 matrix; 3 × 3 × 3 mm voxels). Participants were instructed to relax with their eyes closed but to not fall asleep.

MRI Preprocessing and Data Analysis

FSL software (FMRIB's Software Library; www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) version 5.0 was used to analyze imaging data. Detailed procedures for each analysis will be outlined in the following paragraphs.

MPRAGE preprocessing.

MPRAGE scans underwent brain extraction using BET (Smith 2002) and were then segmented into partial volume maps according to gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using FAST (Zhang et al. 2001). Next, WM and CSF maps were registered to each subject's functional space using FLIRT (Jenkinson and Smith 2001; Jenkinson et al. 2002; Greve and Fischl 2009), thresholded at 0.8 to ensure 80% tissue probability, and binarized. Finally, time courses for the registered thresholded binarized WM and CSF maps were extracted to enter them as nuisance factors in the first-level individual analysis (see below).

Resting-state fMRI preprocessing.

EPI scans for each subject underwent low-pass filtering using a band-pass filter of −1 and 2. Further preprocessing steps included 1) removal of first 4 vol, 2) high-pass filtering cutoff at 0.01 Hz, 3) brain extraction using BET (Smith 2002), 4) motion-correction using McFLIRT (Jenkinson et al. 2002), and 5) scans were excluded if motion >3 mm was detected. To control for possible laterality effects, we flipped the brains of the three patients affected on their lower right extremity to match them with the nine remaining patients with ongoing pain in the lower left extremity. EPI scans were then linearly registered to anatomical scans using FLIRT and nonlinearly registered to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 2-mm standard space using FNIRT. Due to the small size of the Hb, we did not use a spatial smoothing kernel.

Hb seeds.

Left and right MHb and LHb seeds were defined on each subject's MPRAGE scan (see Fig. 1B). The Hb lies immediately dorsal to the posterior commissure and anterior to the pineal gland. Since it contains a high amount of WM, it appears brighter on T1-weighted anatomical scans and can thus be easily delineated from the surrounding CSF and thalamic GM (Lawson et al. 2013). After the Hb was visually located on the anatomical scans, boxes of 3 × 3 × 3 voxels were used to define left and right MHb and LHb. Next, these seeds were registered to each subject's functional scan using FLIRT, which corresponded to 3.99 × 3 × 3 mm in EPI space (see Fig. 1B). LHb and MHb seed registration accuracy from anatomical to functional space was visually inspected and manually adjusted if needed. Finally, time courses for each Hb seed were extracted and entered into first-level individual analysis (see below).

Resting-state fMRI first-level individual analysis.

To control for physiological noise and motion, we included several nuisance factors into the first-level individual analysis. We entered nuisance signals from WM and CSF, as well as six motion parameters (3 rotation and 3 translation generated by motion correction with McFLIRT from preprocessing) into our model. Time courses of the left and right MHb and LHb seeds were also entered into this first-level individual analysis. Images were linearly registered anatomical space using FLIRT and nonlinearly registered MNI 2-mm standard space with FNIRT.

Resting-state fMRI higher-level group analyses.

FEAT was used to perform higher level group analyses using FLAME to investigate Hb rsFC differences between patients and healthy controls. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons using cluster-correction with a z-value >2.3 and P < 0.05. Additionally, since the Hb is known to be a hub connecting the brainstem to frontal brain regions, we were particularly interested in rsFC in the brainstem (see Fig. 2B). However, we did not perform separate region of interest analyses but report results from higher level group analyses described above. We interpreted rsFC in brainstem structures by careful comparison with Duvernoy's brainstem atlas (Naidich et al. 2008).

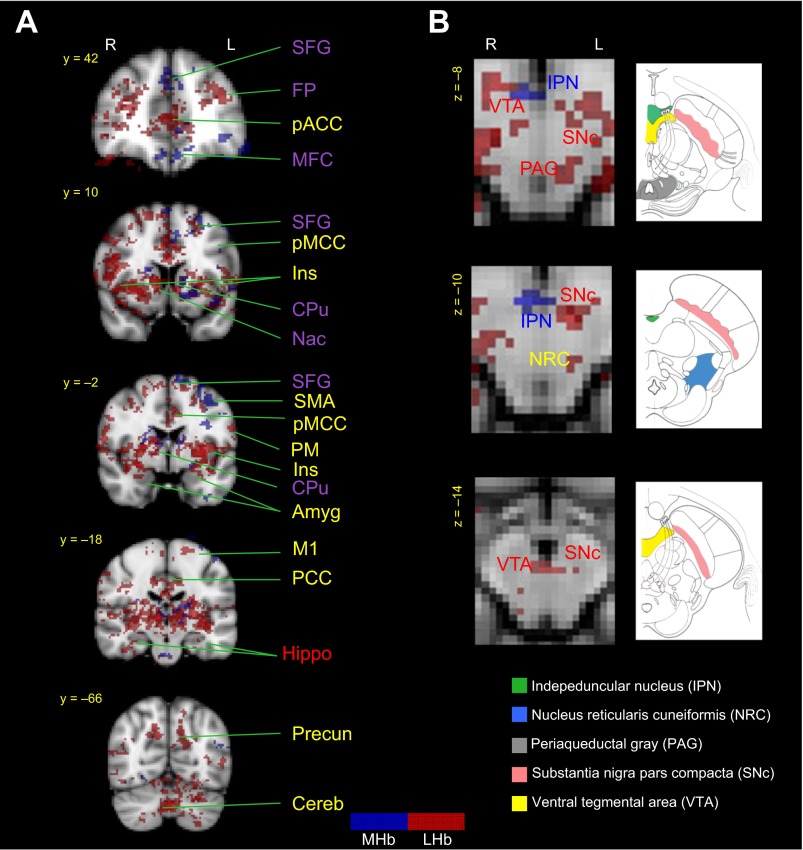

Fig. 2.

MHb (shown in blue) and lateral LHb (shown in red) rsFC in healthy controls. Results confirm previously described anatomical connections in cortical and subcortical structures and in the brainstem. Brain regions labeled in blue show MHb functional connections, brain regions in red indicate LHb functional connections, brain regions in purple designate common MHb and LHb functional connections, and brain regions in yellow indicate previously (anatomically) unreported MHb or LHb functional connections. A: MHb and LHb rsFC in cortical and subcortical brain regions. Healthy controls exhibited Hb rsFC to the CPu, NAc, Ins, FP, SFG, MFC, pACC, dlPFC, SMA, aMCC, pMCC, PM, Amyg, Hippo, Precuneus, and Cereb. B: MHb and LHb rsFC in brainstem structures. Healthy controls exhibited Hb rsFC to the IPN, VTA, SNc, PAG, and NRC. aMCC, anterior midcingulate cortex; Amyg, amygdala; Cereb, cerebellum; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; FP, frontal pole; Hippo, hippocampus; Ins, insula; M1, primary motor cortex; MFC, medial frontal cortex; NRC, nucleus reticularis cuneiformis; pACC, perigenual anterior cingulate cortex; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PM, premotor cortex; pMCC, posterior midcingulate cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; Put, putamen; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; SMA, supplementary motor area.

RESULTS

Subject Demographics

Our patient population consisted of nine females and three males aged between 10 and 17 yr and a mean age ± SE of 14.1 ± 0.7 yr. Nine out of the 12 patients suffered from pain in the lower left extremity; the remaining 3 patients experienced ongoing pain in the lower right extremity. All except one patient reported an injury as onset of their pain condition and experienced ongoing pain in average over 13 ± 2.2 mo. Twelve healthy controls were recruited and matched with regards to sex and were within 1 yr of patients' age (13.8 ± 0.7 yr).

rsFC in Patients and Healthy Controls

No subject scans were excluded because of excessive motion. MHb and LHb rsFC differences between patients with CRPS and healthy controls are summarized in Table 1 (MHb) and Table 2 (LHb).

Table 1.

Medial habenula resting-state functional connectivity in healthy controls and CRPS patients

| MNI Coordinates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | No. Voxels | x | y | z | Z |

| L MHb in healthy controls | |||||

| Primary motor cortex | 1,157 | −28 | −16 | 72 | 3.74 |

| Thalamus | 519 | 8 | −30 | 10 | 3.57 |

| Insula | 361 | −44 | 14 | −4 | 3.51 |

| Frontal pole | 296 | −4 | 46 | −16 | 4.50 |

| Premotor cortex | 284 | −44 | 6 | 32 | 3.86 |

| Paracingulate gyrus | 232 | −12 | 36 | 30 | 3.62 |

| Putamen | 199 | −22 | 2 | −4 | 3.28 |

| Brainstem (rostral ventromedial medulla) | 179 | −2 | −30 | −44 | 4.09 |

| Frontal pole | 159 | 16 | 60 | −12 | 4.03 |

| Precuneus | 148 | −10 | −58 | 40 | 3.59 |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | 143 | −4 | 48 | 12 | 3.10 |

| R MHb in healthy controls | |||||

| Intepeduncular nucleus | 287 | 4 | −12 | −10 | 4.20 |

| Thalamus | 173 | 2 | −24 | 6 | 3.98 |

| L MHb in CRPS patients | |||||

| Thalamus | 146 | −4 | −26 | 2 | 3.70 |

| R MHb in CRPS patients | |||||

| Thalamus | 2,339 | 6 | −4 | −6 | 4.32 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | 509 | 4 | −34 | 8 | 4.04 |

| Brainstem (pontine nuclei) | 500 | −4 | −28 | −48 | 4.43 |

| Cerebellum | 361 | −30 | −54 | −52 | 4.19 |

| Cerebellum | 309 | 16 | −54 | −54 | 4.06 |

| Brainstem | 211 | −22 | −36 | −34 | 4.03 |

| Brainstem | 168 | 0 | −22 | −20 | 4.51 |

| Controls > patients | |||||

| Primary motor cortex/Premotor cortex | 497 | −46 | 2 | 30 | 3.67 |

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 221 | −26 | 20 | 50 | 3.21 |

| Primary motor cortex/supplementary motor area | 181 | −8 | −22 | 54 | 3.27 |

Results were corrected for multiple comparisons using cluster-correction (Z > 2.3; P < 0.05). CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; MHb, medial habenula; R, right; L, left; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute.

Table 2.

Lateral habenula resting-state functional connectivity in healthy controls and CRPS patients

| MNI Coordinates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | No. Voxels | x | y | z | Z |

| L LHb in healthy controls | |||||

| Thalamus | 12,986 | −8 | −16 | 8 | 4.77 |

| Secondary somatosensory cortex | 604 | −58 | −32 | 34 | 4.19 |

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 376 | −22 | 4 | 60 | 4.09 |

| Cerebellum | 316 | 2 | −64 | −40 | 3.55 |

| Primary motor cortex/Primary somatosensory cortex | 216 | 6 | −26 | 68 | 3.55 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 199 | 32 | −14 | −28 | 3.69 |

| Frontal pole | 195 | −36 | 42 | 22 | 4.18 |

| Primary motor cortex | 183 | −30 | −22 | 64 | 3.74 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | 152 | −26 | −28 | −18 | 3.75 |

| R LHb in healthy controls | |||||

| Thalamus | 12,156 | 16 | −28 | 4 | 5.76 |

| Cerebellum | 2,818 | −16 | −72 | −26 | 4.41 |

| Anterior midcingulate cortex | 2,465 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 4.11 |

| Primary motor cortex | 465 | 8 | −30 | 60 | 3.5 |

| Primary somatosensory cortex/superior parietal lobule | 191 | −48 | −30 | 42 | 3.62 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | 165 | 6 | −28 | 24 | 3.84 |

| Frontal pole | 138 | −24 | 40 | 18 | 3.43 |

| L LHb in CRPS patients | |||||

| Insula | 4,424 | −36 | 24 | 2 | 4.6 |

| Cerebellum | 1,868 | −14 | −68 | −14 | 4.62 |

| Brainstem (locus coeruleus/mesenphalic trigeminal nucleus) | 291 | −14 | −34 | −28 | 4.48 |

| R LHb in CRPS patients | |||||

| Thalamus | 1,132 | 12 | −20 | −4 | 4.56 |

| Brainstem (Pontine nuclei) | 214 | 0 | −26 | −48 | 4.27 |

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 183 | 6 | 52 | −2 | 4.15 |

| Thalamus | 162 | −14 | −20 | 2 | 4.74 |

| Posterior cingulate cortex | 146 | 6 | −40 | 26 | 3.66 |

| Frontal orbital cortex | 140 | 46 | 34 | −22 | 4.22 |

| Controls > patients | |||||

| Anterior midcingulate cortex/perigenual anterior cingulate cortex | 531 | −12 | 34 | 22 | 3.31 |

Results were corrected for multiple comparisons using cluster correction (Z >2.3; P < 0.05). LHb, lateral habenula.

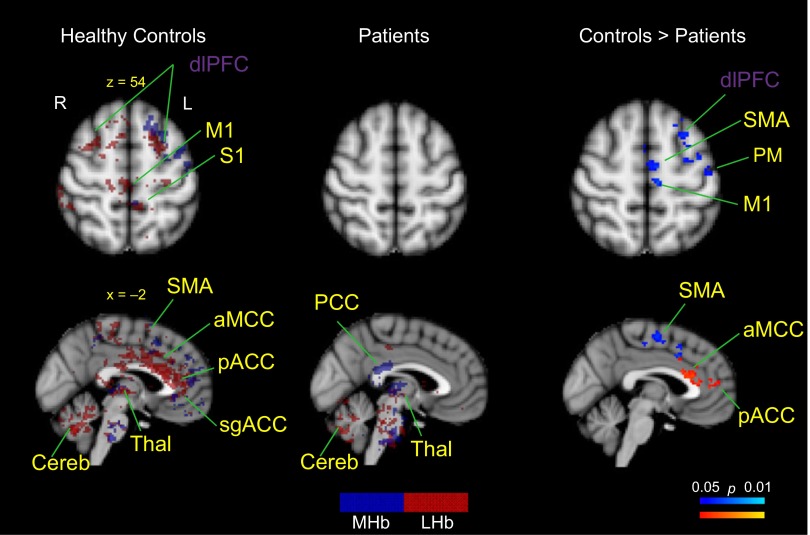

Our analyses indicate that Hb rsFC in healthy controls reflected previously described anatomical connectivity to multiple regions in the brain (see Fig. 1A). For example, in healthy controls, the MHb was functionally connected to the IPN (see Fig. 2B) and additionally showed a widespread network including the thalamus, insula, primary motor cortex (M1), premotor cortex (PM), frontal pole (FP), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (pACC), subgenual ACC (sgACC), anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC), precuneus, CPu, amygdala, and rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) (see Fig. 2A). Interestingly, patients exhibited an overall suppressed MHb rsFC to the rest of the brain, and rsFC was limited to the thalamus, CPu, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and cerebellum (see Fig. 3). Contrast analysis revealed that patients had significantly reduced rsFC of the MHb in M1, PM, supplementary motor region (SMA), aMCC, and dlPFC compared with healthy controls (see Fig. 3). There were no brain regions that patients had significantly higher Hb rsFC to compared with healthy controls.

Fig. 3.

Hb rsFC differences between patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and healthy controls. Patients had Hb rsFC to the Thal, CPu, PCC, and Cereb. Healthy controls had Hb rsFC to the dlPFC, M1, S1, SMA, aMCC, pACC, Thal, and Cereb. Patients had significantly reduced MHb rsFC (shown in blue; right) to the dlPFC, SMA, M1, SMA, and PM compared with healthy controls. Patients also exhibited significantly reduced LHb rsFC (shown in red; right) to the aMCC and pACC. For the main effects (shown at left and middle), brain regions labeled in blue show MHb functional connections, brain regions in red indicate LHb functional connections, brain regions in purple designate common MHb and LHb functional connections, and brain regions in yellow indicate previously (anatomically) unreported MHb or LHb functional connections. All results were corrected for multiple comparisons using cluster correction (P < 0.05). S1, primary somatosensory cortex; Thal, thalamus.

Similarly, LHb rsFC in the healthy state overlapped with previously described anatomical connections (see Fig. 1A). In healthy controls, the LHb was functionally connected to the VTA, SNc, PAG, hippocampus, NAc, and CPu and showed additional functional connections to the thalamus, precuneus, insula, amygdala, sgACC, pACC, aMCC, PCC, M1, primary somatosensory cortex (S1), secondary somatosensory cortex (S2), parahippocampal gyrus, cerebellum, medial frontal cortex, and FP (see Fig. 2, A and B). Patients had LHb rsFC to the thalamus, putamen, insula, cerebellum, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), PCC, and frontal orbital cortex (FOC) (see Fig. 3), and on the brainstem level, to the nucleus central superior (NCS), parabrachial nucleus (PBN), locus coeruleus (LC), mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus (TN), and DRN. Contrast analysis revealed that CRPS patients had significantly reduced LHb rsFC to a cluster that included the aMCC and pACC compared with healthy controls (see Fig. 3). Contrast analysis did not result in any brain regions with higher LHb rsFC in patients compared with healthy controls.

DISCUSSION

Analyses of rsFC have become increasingly popular and are typically used to investigate the intrinsic brain connectivity by identifying anatomically distant brain regions that show a synchronous low-frequency neural activity in individuals at rest. This is the first study to uncover rsFC of the Hb in the healthy and chronic pain state. We have previously reported functional activation of the Hb in response to a noxious heat stimulus in healthy volunteers (Shelton et al. 2012b). Its afferent and efferent pathways have been previously reported in animals (see Fig. 1A) (Hikosaka 2010). We documented similar connections between the Hb and afferent and efferent pathways in humans (Shelton et al. 2012b). Our rsFC results showed that Hb rsFC largely overlapped with previously described anatomical connections of the Hb. Furthermore, we found that compared with healthy control subjects, patients with CRPS exhibited an overall Hb rsFC reduction with the rest of the brain, specifically with the aMCC, dlPFC, SMA, M1, and PM.

Hb rsFC in Healthy Control Subjects

The Hb is a small brain structure in the posterior thalamus that is divided into MHb and LHb components that are functionally different (Andres et al. 1999; Díaz et al. 2011). Because of its location, we carefully selected MHb and LHb seed regions, and it is generally precarious to investigate the function of such a small subcortical structure. We therefore located MHb and LHb on subjects' anatomical scans (Shelton et al. 2012b; Lawson et al. 2013) and used the smallest possible seed size to ensure that the seed is limited to the Hb region. We then registered the seeds to functional space and visually inspected the location accuracy and made adjustments if necessary (see Fig. 1B). We also refrained from using a smoothing kernel as previous studies using 5–12 mm smoothing on their functional scans certainly contaminated the Hb signal with noise from the ventricle and/or surrounding thalamus structures (Salas et al. 2010; Noonan et al. 2011).

Our rsFC findings support previously described anatomical connections of the Hb in healthy control subjects (see Figs. 1A and 2, A and B). For example, the MHb in healthy controls showed rsFC with the IPN, NAc, CPu, and frontal areas such as M1, PM, SMA, FP, and dlPFC. Additionally, the MHb was functionally connected to previously undefined brain regions, for example, the thalamus, insula, amygdala, pACC, sgACC, aMCC, precuneus, and in the brainstem, RVM. Similarly, the LHb rsFC mapped onto anatomical LHb regions. For example, healthy subjects exhibited functional connections between the LHb and frontal brain areas (M1/S1, S2, FP, and dlPFC), subcortical regions (thalamus, CPu, NAc, and hippocampus), and brainstem structures (PAG, VTA, and SNc). The LHb receives inputs from numerous brain regions such as the lateral hypothalamus, basal ganglia, NAc, and frontal brain regions; its main outputs go to the PAG, VTA, and SNc (Andres et al. 1999; Bianco and Wilson 2009; Díaz et al. 2011), which are predominantly nuclei that regulate dopaminergic and serotonergic systems (Aizawa et al. 2012). Additionally, we found functional connections between the Hb and the PAG, a region involved in a number of processes including pain modulation (Behbehani 1995; Linnman et al. 2012), as well to the RVM, which is known to send excitatory and inhibitory fibers to dorsal horn spinal cord neurons and is thus actively involved in pain modulation (Fields et al. 1995). Accordingly, our results support our previous structural connectivity findings (Shelton et al. 2012b) and suggest that there are large overlaps between Hb functional and structural connections.

Hb rsFC in Patients with CRPS

Our chronic pain sample included pediatric patients with CRPS. CRPS usually follows a seemingly trivial injury to the limbs and affects multiple brain systems including the somatosensory cortex, parietal regions, basal ganglia and frontal areas that seem to correlate with known changes in some of the behavioral measures noted in the syndrome (e.g., parietal changes and hemi-inattention; basal ganglia and movement disorders, etc.). The Hb is thereby of particular interest for pain processing since it acts as a relay station between forebrain structures and brainstem nuclei, many of which are involved in pain processing (e.g., VTA, IPN, SNc, PAG, and RVM; see Fig. 1A; Shelton et al. 2012a).

Our rsFC analysis revealed that patients with CRPS had overall suppressed functional connections between the Hb and the rest of the brain. Patients exhibited functional connections between the MHb and the thalamus, cerebellum, PCC, and on the brainstem level, the pontine nuclei (see below). Furthermore, the LHb functionally connected to the thalamus, insula, cerebellum, vmPFC, PCC, and FOC, and in the brainstem, to the NCS, PBN, LC, TN, and DRN. Accordingly, patients exhibited reduced rsFC and, additionally, showed an altered Hb rsFC pattern with previously undefined structural connections.

Patients with CRPS did not show MHb rsFC to the IPN compared with controls. The IPN is located in the midbrain and activity in this region is involved in diffuse inhibitory actions on a number of brain areas by inhibiting dopamine release from in mesocortical, mesolimbic, and mesostriatal dopaminergic neurons (Nishikawa et al. 1986), and interestingly, lesions of the Hb result in dopamine increase in these brain regions (Lisoprawski et al. 1980; Nishikawa et al. 1986). Moreover, stimulation of the LHb results in an inhibition of dopaminergic neurons in the SNc and VTA (Christoph et al. 1986). Taken together, its connections to dopaminergic brain regions may thus relate to the implication of the Hb in reward (Ullsperger and von Cramon 2003), anti-reward (Matsumoto and Hikosaka 2007, 2009), and pain processes (Leknes and Tracey 2008). Patients' overall rsFC suppression may also converge with decreased dopamine levels previously demonstrated in fibromyalgia (Wood et al. 2007), burning mouth syndrome (Hagelberg et al. 2003), and restless leg syndrome (Connor et al. 2009). Patients had LHb rsFC to the DRN that have been linked to serotoninergic functions. Our results revealed a unique Hb rsFC for patients with CRPS to brainstem structures that have not been previously linked to the Hb, for example, the LC, PBN, and NCS, all of which have repeatedly been associated with pain processing and pain modulation (Leichnetz et al. 1978; Segal 1979; Cechetto et al. 1985). These functional connections, together with altered Hb rsFC to the rest of the brain, may contribute to spontaneous, ongoing pain in patients. For example, it is conceivable that increased afferent drive from the basal ganglia to the Hb (Shabel et al. 2012) may affect Hb outputs to the brainstem and, consequently, diminish pain modulation and reward processing. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution, as there are no known anatomical connections between the Hb and these brainstem nuclei and could potentially be mediated through secondary anatomical connections from other brain regions.

Hb rsFC Group Differences

CRPS patients had significantly lower rsFC compared with healthy controls, which also, intriguingly, was found in similar locations for MHb and LHb. Notably, patients had significantly reduced rsFC among the MHb and M1 and PM, SMA, aMCC, and dlPFC compared with healthy controls. Many patients with CRPS show significant limitations of motor control and movement secondary to their pain. We therefore suggest that rsFC reductions in motor areas may reflect altered Hb rsFC with systems involved in motor planning and execution (i.e., SMA and M1; Kirveskari et al. 2010; Schilder et al. 2012) and may originate from negative effects of limb disuse (Bruehl and Chung 2006). Furthermore, patients showed reduced LHb rsFC to a cluster located in the pACC, pgACC, and aMCC region. Reduced rsFC in patients in brain regions responsible for higher-level cognitive and affective processes are in line with previous studies providing evidence that patients with CRPS have decreased perceptual learning abilities (Maihöfner and DeCol 2007), emotional processing (Geha et al. 2008), as well as reduced decision-making skills (Apkarian et al. 2004). Furthermore, the reduced rsFC from both MHb and LHb to the aMCC and pACC may link chronic pain states to changes in negative affect, pain, and cognitive control (Vogt 2005; Geha et al. 2008; Shackman et al. 2011). Another interesting finding relates to the reduced rsFC to the pgACC previously implicated in pain inhibition systems (Petrovic et al. 2002; Wager et al. 2004; Bingel et al. 2006) and to the dlPFC repeatedly associated with pain modulation (Lorenz et al. 2003; Brighina et al. 2004; Fierro et al. 2010), perceived control over pain (Pariente et al. 2005; Wiech et al. 2006), and pain catastrophizing (Seminowicz and Davis 2006).

Study Limitations

There are several study limitations. 1) Sample: a study caveat constituted the patient sample, as findings with 12 patients will only provide limited significance. Additionally, pediatric subjects generally exhibit more movement in the MRI compared with adults and may therefore result in higher noise issues. We were careful to reduce movement noise by applying band-pass filtering and motion correction to our scans. 2) Regions outside of classic defined Hb connectivity: our analyses revealed Hb rsFC to brain regions, such as the cerebellum, that have no known pathways with the Hb. It has previously been shown that there are large overlaps between functional and structural connections in the brain (van den Heuvel and Mandl 2009). Our findings may therefore arise from secondary connections between brain regions. The current approach can elucidate which brain regions communicate with each other, either as entire networks (e.g., default-mode network) or as seed-based rsFC between a region of interest and the rest of the brain. Intriguingly, study results support the existence of direct or indirect (i.e., through other brain regions) anatomical connections to ensure a high level of interaction between brain areas (Damoiseaux and Greicius 2009; Greicius et al. 2009; Honey et al. 2009; Hermundstad et al. 2013). From a clinical standpoint, this approach can be used to provide insight into functional networks and/or functional coupling between brain regions in various disorders (Greicius 2008). Thus some of the regions shown in Figs. 2 and 3 (regions with yellow labels) may be a result of direct or indirect connectivity. 3) Imaging resolution: the voxel size that was used to obtain whole brain acquisitions at a relatively short TR may have hindered our ability to precisely localize the Hb in functional space and may not allow for multivoxel averaging to reduce noise in the seed signal.

Conclusions

We believe that this is the first study to investigate rsFC of the Hb in human chronic pain. Other studies have implicated the Hb in a number of diseases including depression (Carlson et al. 2013), nicotine addiction (Baldwin et al. 2011), and bipolar disorder (Savitz et al. 2011b). The Hb is likely involved in modulating multiple biological processes that include pain and analgesia, stress response, and reward-punishment (Thornton et al. 1985; Sugama et al. 2002; Hikosaka 2010). In the healthy state, our results showed that the Hb may act as a relay station between frontal and brainstem regions to regulate outputs to brainstem nuclei. In the chronic pain state, we found decreased rsFC from the Hb to brain regions implicated in motor, affective, and pain modulatory/inhibitory processes. Mechanistically, it is possible that the lack of frontal regulatory/modulatory inputs may alter neuronal activity in brainstem structures, which may then contribute to patients' symptomatology such as a high levels of spontaneous pain (Baron 2000), increased anxiety (Geha et al. 2008), and decreased motor activity (Kirveskari et al. 2010; Schilder et al. 2012).

GRANTS

This study was primarily supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants R01-NS-065051 and K24-NS-064050 (to D. Borsook), by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K23 Career Development Award HD-067202 (to L. E. Simons), and by a Grant from the Mayday Foundation, New York.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.E. analyzed data; N.E., L.B., and D.B. interpreted results of experiments; N.E. prepared figures; N.E. drafted manuscript; N.E., L.E.S., P.S., L.B., and D.B. edited and revised manuscript; N.E., S.S., L.E.S., A.L., P.S., L.B., and D.B. approved final version of manuscript; S.S., A.L., L.B., and D.B. conception and design of research; S.S. performed experiments.

REFERENCES

- Aizawa H, Kobayashi M, Tanaka S, Fukai T, Okamoto H. Molecular characterization of the subnuclei in rat habenula. J Comp Neurol 520: 4051–4066, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres KH, von Düring M, Veh RW. Subnuclear organization of the rat habenular complexes. J Comp Neurol 407: 130–150, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Sosa Y, Krauss BR, Thomas PS, Fredrickson BE, Levy RE, Harden RN, Chialvo DR. Chronic pain patients are impaired on an emotional decision-making task. Pain 108: 129–136, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Thomas PS, Krauss BR, Szeverenyi NM. Prefrontal cortical hyperactivity in patients with sympathetically mediated chronic pain. Neurosci Lett 311: 193–197, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin PR, Alanis R, Salas R. The role of the habenula in nicotine addiction. J Addict Res Ther S1: pii 002, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Geha PY, Apkarian AV, Chialvo DR. Beyond feeling: chronic pain hurts the brain, disrupting the default-mode network dynamics. J Neurosci 28: 1398–1403, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Schnitzer TJ, Bauer WR, Apkarian AV. Brain morphological signatures for chronic pain. PLoS One 6: e26010, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Peripheral neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to symptoms. Clin J Pain 16: S12–20, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Schwartzman RJ, Kiefer RT, Rohr P, Moulton EA, Wallin D, Pendse G, Morris S, Borsook D. CNS measures of pain responses pre- and post-anesthetic ketamine in a patient with complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med 2009. February 25 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behbehani MM. Functional characteristics of the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Prog Neurobiol 46: 575–605, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta CA, Dross N, Guiterrez-Triana JA, Ryu S, Carl M. Habenula circuit development: past, present, and future. Front Neurosci 6: 51, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco IH, Wilson SW. The habenular nuclei: a conserved asymmetric relay station in the vertebrate brain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364: 1005–1020, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingel U, Lorenz J, Schoell E, Weiller C, Büchel C. Mechanisms of placebo analgesia: rACC recruitment of a subcortical antinociceptive network. Pain 120: 8–15, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brighina F, Piazza A, Vitello G, Aloisio A, Palermo A, Daniele O, Fierro B. rTMS of the prefrontal cortex in the treatment of chronic migraine: a pilot study. J Neurol Sci 227: 67–71, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, Chung OY. Psychological and behavioral aspects of complex regional pain syndrome management. Clin J Pain 22: 430–437, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S. An update on the pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Anesthesiology 113: 713–725, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson PJ, Diazgranados N, Nugent AC, Ibrahim L, Luckenbaugh DA, Brutsche N, Herscovitch P, Manji HK, Zarate CA, Drevets WC. Neural correlates of rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in treatment-resistant unipolar depression: a preliminary positron emission tomography study. Biol. Psychiatry 73: 1213–1221, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, D'Agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Cocito D, Paolasso I, Isoardo G, Geminiani G. Altered resting state attentional networks in diabetic neuropathic pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81: 806–811, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, Sacco K, D'Agata F, Duca S, Cocito D, Geminiani G, Migliorati F, Isoardo G. Low-frequency BOLD fluctuations demonstrate altered thalamocortical connectivity in diabetic neuropathic pain. BMC Neurosci 10: 138, 2009a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, Sacco K, Duca S, Cocito D, D'Agata F, Geminiani GC, Canavero S. Altered resting state in diabetic neuropathic pain. PLoS One 4: e4542, 2009b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cechetto DF, Standaert DG, Saper CB. Spinal and trigeminal dorsal horn projections to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 240: 153–160, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph G, Leonzio R, Wilcox K. Stimulation of the lateral habenula inhibits dopamine-containing neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the rat. J Neurosci 6: 613–619, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JR, Wang XS, Allen RP, Beard JL, Wiesinger JA, Felt BT, Earley CJ. Altered dopaminergic profile in the putamen and substantia nigra in restless leg syndrome. Brain 132: 2403–2412, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Greicius MD. Greater than the sum of its parts: a review of studies combining structural connectivity and resting-state functional connectivity. Brain Struct Funct 213: 525–533, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz E, Bravo D, Rojas X, Concha ML. Morphologic and immunohistochemical organization of the human habenular complex. J Comp Neurol 519: 3727–3747, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Malick A, Burstein R. Dorsal horn projection targets of ON and OFF cells in the rostral ventromedial medulla. J Neurophysiol 74: 1742–1759, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro B, Tommaso De M, Giglia F. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during capsaicin-induced pain: modulatory effects on motor cortex. Exp Brain Res 203: 31–38, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund W, Wunderlich AP, Stuber G, Mayer F, Steffen P, Mentzel M, Weber F, Schmitz B. Different activation of opercular and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS I) compared with healthy controls during perception of electrically induced pain: a functional MRI study. Clin J Pain 26: 339–347, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto M, Ushida T, Zinchuk VS, Yamamoto H, Yoshida S. Contralateral thalamic perfusion in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Lancet 354: 1790–1791, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geha PY, Baliki MN, Harden RN, Bauer WR, Parrish TB, Apkarian AV. The brain in chronic CRPS pain: abnormal gray-white matter interactions in emotional and autonomic regions. Neuron 60: 570–581, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grachev ID, Fredrickson BE, Apkarian AV. Abnormal brain chemistry in chronic back pain: an in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Pain 89: 7–18, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grachev ID, Thomas PS, Ramachandran TS. Decreased levels of N-acetylaspartate in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in a case of intractable severe sympathetically mediated chronic pain (complex regional pain syndrome, type I). Brain Cogn 49: 102–113, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb Cortex 19: 72–78, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 21: 424–430, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve DN, Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage 48: 63–72, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagelberg N, Forssell H, Rinne JO, Scheinin H, Taiminen T, Aalto S, Luutonen S, Någren K, Jääskeläinen S. Striatal dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in burning mouth syndrome. Pain 101: 149–154, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Burton AW, Perez RS, Richardson K, Swan M, Barthel J, Costa B, Graciosa JR, Bruehl S. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med 14: 180–229, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermundstad AM, Bassett DS, Brown KS, Aminoff EM, Clewett D, Freeman S, Frithsen A, Johnson A, Tipper CM, Miller MB, Grafton ST, Carlson JM. Structural foundations of resting-state and task-based functional connectivity in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 6169–6174, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuvel van den M, Mandl R. Functionally linked resting state networks reflect the underlying structural connectivity architecture of the human brain. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 3127–3141, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 503–513, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Thiran JP, Meuli R, Hagmann P. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 2035–2040, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide JS, Li CS. Error-related functional connectivity of the habenula in humans. Front Hum Neurosci 5: 25, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17: 825–841, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 5: 143–156, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirveskari E, Vartiainen NV, Gockel M, Forss N. Motor cortex dysfunction in complex regional pain syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 121: 1085–1091, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klega A, Eberle T, Buchholz HG, Maus S, Maihöfner C, Schreckenberger M, Birklein F. Central opioidergic neurotransmission in complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology 75: 129–136, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson RP, Drevets WC, Roiser JP. Defining the habenula in human neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 64: 772–777, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel A, Becerra L, Wallin D, Moulton EA, Morris S, Pendse G, Jasciewicz J, Stein M, Aiello-Lammens M, Grant E, Berde C, Borsook D. fMRI reveals distinct CNS processing during symptomatic and recovered complex regional pain syndrome in children. Brain 131: 1854–1879, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichnetz GR, Watkins L, Griffin G, Murfin I, Mayer DJ. The projection from nucleus raphe magnus and other brainstem nuclei to the spinal cord in the rat: a study using the HRP blue-reaction. Neurosci Lett 8: 119–124, 1978 [Google Scholar]

- Leknes S, Tracey I. A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 314–320, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnman C, Moulton EA, Barmettler G, Becerra L, Borsook D. Neuroimaging of the periaqueductal gray: state of the field. Neuroimage 60: 505–522, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisoprawski A, Herve D, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Tassin JP. Selective activation of the mesocortico-frontal dopaminergic neurons induced by lesion of the habenula in the rat. Brain Res 183: 229–234, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz J, Minoshima S, Casey K. Keeping pain out of mind: the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in pain modulation. Brain 126: 1079–1091, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai JK, Paxinos G, Voss T. Atlas of the Human Brain (3rd ed.). New York: Elsevier, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Maihöfner C, Baron R, DeCol R, Binder A, Birklein F, Deuschl G, Handwerker HO, Schattschneider J. The motor system shows adaptive changes in complex regional pain syndrome. Brain 130: 2671–2687, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihöfner C, DeCol R. Decreased perceptual learning ability in complex regional pain syndrome. Eur J Pain 11: 903–909, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihöfner C, Forster C, Birklein F, Neundörfer B, Handwerker HO. Brain processing during mechanical hyperalgesia in complex regional pain syndrome: a functional MRI study. Pain 114: 93–103, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihöfner C, Handwerker HO, Neundörfer B, Birklein F. Cortical reorganization during recovery from complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology 63: 693–701, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihöfner C, Neundörfer B, Birklein F, Handwerker HO. Mislocalization of tactile stimulation in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. J Neurol 253: 772–779, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature 447: 1111–1115, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Representation of negative motivational value in the primate lateral habenula. Nat Neurosci 12: 77–84, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidich TP, Duvernoy HM, Delman BN, Sorensen AG, Kollias SS, Haacke EM. Duvernoy's Atlas of the Human Brain Stem and Cerebellum: High-Field MRI, Surface Anatomy, Internal Structure, Vascularization and 3D Sectional Anatomy. New York: Springer, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Fage D, Scatton B. Evidence for, and nature of, the tonic inhibitory influence of habenulointerpeduncular pathways upon cerebral dopaminergic transmission in the rat. Brain Res 373: 324–336, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan MP, Mars RB, Rushworth MF. Distinct roles of three frontal cortical areas in reward-guided behavior. J Neurosci 31: 14399–14412, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariente J, White P, Frackowiak RS, Lewith G. Expectancy and belief modulate the neuronal substrates of pain treated by acupuncture. Neuroimage 25: 1161–1167, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Kalso E, Petersson KM, Ingvar M. Placebo and opioid analgesia–imaging a shared neuronal network. Science 295: 1737–1740, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleger B, Ragert P, Schwenkreis P, Förster AF, Wilimzig C, Dinse H, Nicolas V, Maier C, Tegenthoff M. Patterns of cortical reorganization parallel impaired tactile discrimination and pain intensity in complex regional pain syndrome. Neuroimage 32: 503–510, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Baldwin P, de Biasi M, Montague PR. BOLD responses to negative reward prediction errors in human habenula. Front Hum Neurosci 4: 36, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz JB, Bonne O, Nugent AC, Vythilingam M, Bogers W, Charney DS, Drevets WC. Habenula volume in post-traumatic stress disorder measured with high-resolution. MRI Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 1: 7, 2011a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz JB, Nugent AC, Bogers W, Roiser JP, Bain EE, Neumeister A, Zarate CA, Manji HK, Cannon DM, Marrett S, Henn F, Charney DS, Drevets WC. Habenula volume in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry 69: 336–343, 2011b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz JB, Rauch SL, Drevets WC. Reproduced from Habenula volume in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Mol Psychiatry 18: 523, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilder JC, Schouten AC, Perez RS, Huygen FJ, Dahan A, Noldus LP, van Hilten JJ, Marinus J. Motor control in complex regional pain syndrome: a kinematic analysis. Pain 153: 805–812, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M. Serotonergic innervation of the locus coeruleus from the dorsal raphe and its action on responses to noxious stimuli. J Physiol 286: 401–415, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. Cortical responses to pain in healthy individuals depends on pain catastrophizing. Pain 120: 297–306, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabel SJ, Proulx CD, Trias A, Murphy RT, Malinow R. Input to the lateral habenula from the basal ganglia is excitatory, aversive, and suppressed by serotonin. Neuron 74: 475–481, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter HA, Fox AS, Winter JJ, Davidson RJ. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 154–167, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton L, Becerra L, Borsook D. Unmasking the mysteries of the habenula in pain and analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 96: 208–19, 2012a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton L, Pendse G, Maleki N, Moulton EA, Lebel A, Becerra L, Borsook D. Mapping pain activation and connectivity of the human habenula. J Neurophysiol 107: 2633–2648, 2012b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 17: 1431–1455, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Cho BP, Baker H, Joh TH, Lucero J, Conti B. Neurons of the superior nucleus of the medial habenula and ependymal cells express IL-18 in rat CNS. Brain Res 958: 1–9, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton EW, Evans JA, Harris C. Attenuated response to nomifensine in rats during a swim test following lesion of the habenula complex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 87: 81–85, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger M, von Cramon DY. Error monitoring using external feedback: specific roles of the habenular complex, the reward system, and the cingulate motor area revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci 23: 4308–4314, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 533–544, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, Davidson RJ, Kosslyn SM, Rose RM, Cohen JD. Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science 303: 1162–1167, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiech K, Kalisch R, Weiskopf N, Pleger B, Stephan KE, Dolan RJ. Anterolateral prefrontal cortex mediates the analgesic effect of expected and perceived control over pain. J Neurosci 26: 11501–11509, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PB, Schweinhardt P, Jaeger E, Dagher A, Hakyemez H, Rabiner EA, Bushnell MC, Chizh BA. Fibromyalgia patients show an abnormal dopamine response to pain. Eur J Neurosci 25: 3576–3582, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 20: 45–57, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]