Abstract

Little is known about the influence of genetic diversity on stroke recovery. One exception is the polymorphism in brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a critical neurotrophin for brain repair and plasticity. Humans have a high-frequency single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the prodomain of the BDNF gene. Previous studies show that the BDNF Val66Met variant negatively affects motor learning and severity of acute stroke. To investigate the impact of this common BDNF SNP on stroke recovery, we used a mouse model that contains the human BDNF Val66Met variant in both alleles (BDNFM/M). Male BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M littermates received sham or transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. We assessed motor function regularly for 6 months after stroke and then performed anatomical analyses. Despite reported negative association of the SNP with motor learning and acute deficits, we unexpectedly found that BDNFM/M mice displayed significantly enhanced motor/kinematic performance in the chronic phase of motor recovery, especially in ipsilesional hindlimb. The enhanced recovery was associated with significant increases in striatum volume, dendritic arbor, and elevated excitatory synaptic markers in the contralesional striatum. Transient inactivation of the contralateral striatum during recovery transiently abolished the enhanced function. This study showed an unexpected benefit of the BDNFVal66Met carriers for functional recovery, involving structural and molecular plasticity in the nonstroked hemisphere. Clinically, this study suggests a role for BDNF genotype in predicting stroke recovery and identifies a novel systems-level mechanism for enhanced motor recovery.

Keywords: BDNF, cerebral ischemia, gait, motor function, striatum, Val66Met polymorphism

Introduction

Stroke remains a leading cause of long-term disability in the United States. Although adaptive neuroplasticity and remodeling occur for an extended period after stroke, most patients have incomplete recovery (Carmichael, 2006; Nudo, 2007). While the natural history of spontaneous stroke recovery and imaging studies in humans have provided some understanding in recovery (Cramer, 2008), the biological determinants of endogenous recovery after stroke remain to be elucidated.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) promotes neuronal survival, differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and angiogenesis in normal and ischemic tissue (Chao, 2003; Kermani et al., 2005; Wagner et al., 2005). A common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the human BDNF gene leads to a substitution of a valine to methionine at codon 66 (Val66Met). The BDNF SNP occurs only in humans, with a prevalence ranging from 20 to 30% in Caucasians up to 70% in the Asian population (Egan et al., 2003; He et al., 2007). Clinical studies suggested that the Met allele negatively impacts stroke recovery among survivors of subarachnoid hemorrhage (Siironen et al., 2007; Vilkki et al., 2008; Mirowska-Guzel et al., 2012). Additionally, mice with the SNP exhibit angiogenic and behavioral deficits in an acute phase (Qin et al., 2011). It was, however, the Met allele that promoted the recovery of executive function in individuals with traumatic brain injury (Krueger et al., 2011), indicating a more complex role of the SNP, possibly depending on the injury context and outcome parameters.

Knock-in mice homozygous for the Met allele (BDNFM/M) display similar phenotypic hallmarks as humans who carry the SNP: smaller hippocampus, memory deficits, and increased anxiety-related behavior (Sklar et al., 2002; Egan et al., 2003; Sen et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2006). Moreover, the neurons cultured from these mice showed reduced regulated BDNF secretion but normal constitutive secretion (Chen et al., 2006). Regulated BDNF secretion modulates synaptic plasticity (Poo, 2001; Kline et al., 2010). Specifically, it regulates the maturation of inhibitory synapses, which fosters a network-level adaptation for homeostasis between excitation and inhibition (Seil and Drake-Baumann, 2000; Hong et al., 2008).

Ischemic stroke resulting from occlusion of the proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) primarily affects the striatum, a subcortical structure that exhibits activity-dependent plasticity and is important for controlling movement and motor learning (Dang et al., 2006; Kreitzer and Malenka, 2008; Bateup et al., 2010). Several studies have reported the impact of this BDNF SNP on cognitive function. The high occurrence of the SNP in humans, however, raises the intriguing possibility that the Met allele may confer selective advantages through noncognitive function. To address the impact of the SNP on functional recovery in chronic stroke, we assessed long-term motor/gait functions, which are relevant to human recovery, in mice carrying the SNP and asked whether the functional recovery is coupled with structural and morphological plasticity. Here we report that the BDNFM/M mice display unexpected enhancement of motor function during stroke recovery and that the enhancement is associated with structural and synaptic plasticity in the contralesional striatum.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Medical College of Cornell University approved the use of animals and procedures performed. A total of 187 BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M male mice were used for the study. To prevent genetic drifting and to maintain the phenotype of the mice, the BDNF SNP mice have been backcrossed to C57bl/6 every 2 years. The mice used in this study are 10× and 11× backcrossed. We used BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M littermates from respective 10× or 11× heterozygote mating to match genetic background within a given experiment for the controlled preclinical studies. The genotyping procedure has been described (Chen et al., 2006). A maximum of five mice were housed in a cage at the institute's animal facility with 12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum in their cage. Due to the nature of a long-term study, mice were given a code (either tattoo or ear tag) at the beginning of the study. Surgeons who performed sham or middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) procedure and other individuals who performed pretraining and postbehavior testing were blinded to the animals' genotype. The code was revealed after data were collected.

Chronic stroke recovery model.

Male BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice at 3–4 months of age were randomly assigned to undergo sham or transient MCAO by an intraluminar method as described previously (Cho et al., 2005; Qin et al., 2011). Mice were anesthetized briefly with isofluorane (1.5–2.0%) with a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen (30/70%). A fiber optic probe connected to a laser-Doppler flowmeter (Periflux System 5010, Perimed) was glued to the right parietal bone (2 mm posterior and 5 mm lateral to bregma) for continuous monitoring of cerebral blood flow (CBF) before, during, and after MCAO. Sham surgery consisted of exposure of the right carotid artery at its bifurcation, but without occlusion. The surgical site was exposed for 40 min to balance the anesthesia time with the MCAO group. Postsurgical care was the same in the two groups. The proximal MCA was transiently occluded using a 6-0 Teflon-coated black monofilament surgical suture (Doccol) for 30 min. The transient MCAO perturbs blood flow in the striatum, thalamus, and the cortex with the striatum as the structure most affected by the occlusion. The relatively short duration of 30 min MCAO used in this study produced sizable infarction in the MCA territory ∼35 mm3 (∼20% ipsilesional hemisphere) at 3 d poststroke (Qin et al., 2011), which was accompanied by acute motor and gait impairment with good recovery. Core body temperature was kept at 37 ± 0.5°C during the entire procedure. Mice were then placed in a recovery cage, where the body temperatures were maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C until the animal regained consciousness and resumed activity. The mice were then returned to their home cages where they were previously housed together. Animals that exhibited both CBF reduction of >80% during MCAO and CBF recovery of >80% by 10 min after reperfusion were included in the study. Moxifloxacin (100 mg/kg) was daily administered subcutaneously for 3 d to reduce acute poststroke peripheral infections (Meisel et al., 2004). In addition, saline was subcutaneously administered daily and hydrogel (ClearH2O) was given to prevent dehydration during the first week of the poststroke period. Mice typically started to regain body weight around day 5–6 and continued to recover from stroke.

Behavior assessment.

Rotarod performance and gait analysis were conducted during a light phase of the cycle as previously described (Qin et al., 2011). The rotarod tests the ability of mice to stay on top of a rotating rod. A rotarod device (Med Associates) was set to accelerate from 4 to 40 rpm over the course of 5 min. The animals were pretrained for 1 week, and the performance recorded on the last day before ischemia was used for preischemic baseline for each animal. Poststroke testing was performed during acute (days), subacute (weeks), and recovery (up to 6 months) phases following stroke. The latency to fall from the rod (performance) was averaged from five trials. Initial poststroke rotarod testing was done on day 6.

Gait changes were assessed using a Noldus Catwalk XT gait analysis system (Noldus Information Technology), which is designed to test important gait functions that are relevant to specific disease conditions (Hamers et al., 2006; Neumann et al., 2009). The CatWalk measures kinematics of gait while the mouse walks from one end of a flat surface to another. Footprints were identified and digitally recorded when the light changes with paw placement on the glass-walking surface. We preselected several gait parameters that are biologically meaningful and relevant to stroke recovery (Qin et al., 2011). These include walk speed and interlimb coordination to gauge overall gait function. For detecting asymmetry, we determined paw contact area, intensity of paw pressure, stride length, and swing speed in four limbs: left front (LF), right front (RF), left hind (LH), and right hind (RH) paw. Mice were pretrained for 2 weeks to cross an illuminated glass walkway three consecutive times, a necessary step to obtain quantifiable digital signals. The average recording on the last 2 d before ischemia was used for preischemic baseline for each animal. Behavioral data were presented as percentage of preischemic baseline (mean ± SEM) to account for interanimal variability.

Tissue preparation.

Brains were excised, frozen, and sectioned using a cryostat (Leica). Because infarct typically spans ∼6 mm rostrocaudally starting from +2.8 mm from bregma and extending to −3.8 mm, we used an unbiased stereological sampling strategy to collect tissue in the entire region that included infarct. Tissue sections were collected serially at 600 μm intervals for the analysis of infarct volume and subregion volume analysis. Tissue between the intervals was sectioned and cut in half and collected for each hemisphere to determine mRNA levels. Separated cohorts of mice were perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was postfixed, left in a 30% sucrose solution overnight, and sectioned at a 30 μm thickness using a microtome for immunohistochemistry.

Subregion volume estimation.

Using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss), the entire volume of both hemispheres was measured at 4× objective magnification. From a total of 13 serially collected coronal sections at 600 μm intervals, the following morphological criteria were used to determine the boundary of cortex, striatum, and hippocampus according to the literature (Xie et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). The cortex (+2.8 to −3.8 mm from bregma) was defined by the corpus callosum and external capsule, with the ventral boundary by the rhinal fissure. The superior, lateral, medial, and ventral boundaries of the striatum (+1.7 to −2.0 mm) were defined by the corpus callosum, external capsule, lateral ventricle/corpus callosum, and anterior commissure respectively. The nucleus accumbens was excluded from calculations. The external capsule, alveus of hippocampus, and white matter were used as boundary landmarks for the hippocampus (−0.9 to −3.8 mm). The subregional volume was obtained by integrating volume from each sectional area times distance (600 μm). The value was presented as percentage of contralesional hemispheric volume.

Golgi staining/tracing.

Golgi impregnation was done using a FD Rapid GolgiStain method (Chen et al., 2006). Brains were embedded in a 3% agarose solution, blocked, cut using a vibratome (150 μm sections), and mounted onto 0.3% gelatin-coated slides. Slides were then dehydrated through graded ethanols, cleared with Histoclear (3 × 5 min), and coverslipped with DPX mounting medium. Slides containing the Golgi-impregnated brain sections were coded before quantitative analysis. Neurons with isolated cell body, untruncated dendrities, and homogeneous impregnation were randomly chosen from the dorsal striatum and hippocampal dentate gyrus. For each group, 25 medium spiny neurons and 12 hippocampal dentate gyrus neurons were selected. Neurons were traced under 40× magnification using Neurolucida software. The morphological traits of cells (cell body perimeter, cell body area, Sholl analysis, and fractal dimension analysis) were analyzed using a Neuroexplorer software. The code was revealed after the analysis was completed.

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR for gene expression.

Vesicular glutamate transporter 1 and 2 (VGLUT1, VGLUT2) and vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) mRNA were quantified with real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR using fluorescent TaqMan technology as previously described (Kim et al., 2008). PCR primers and probes specific for VGLUT1, VGLUT2, VGAT, and β-actin were obtained as TaqMan predeveloped assay reagents for gene expression (Applied Biosystems). β-Actin was used as an internal control for normalization of samples. The PCR was performed using FastStart Universal Probe Master (Roche) and Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Reactions were performed in 20 μl total volume and incubated at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C.

Immunohistochemistry.

For DAB staining, endogenous peroxidase activity was first depleted by incubation with hydrogen peroxide. After blocking in 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 (1:1000; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) and PSD95 (1:500; Invitrogen), followed by Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Labs). For fluorescence, sections incubated with primary antibodies were washed with PBS, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (1:200; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature, and examined under a fluorescent microscope or laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). The number of VGLUT1-immunopositive and VGLUT2-immunopositive dots was counted in two sections at the level of striatum (+1.2 and +0.6 mm from bregma) per animal. We randomly selected nine framed areas (0.1 mm2 each) in the contralesional striatum. The number of dots within each frame was counted and the total number of immunopositive dots per frame was averaged and divided by area to obtain density per animal.

Stereotaxic injections.

Mice placed in a stereotaxic frame received intracerebral injections of saline or muscimol (0.2 μg/μl, 1 μl) in the contralesional dorsolateral striatum (0.62 mm anterior, 2 mm lateral, 4 mm ventral from bregma). The solution was delivered at a fixed rate of 82 nl/min using a microinject system. Behavioral testing was performed by individuals who were blind to the genotype and treatment.

Statistics.

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The comparisons of anatomical, morphological, and biological data between the two groups were made using the Student's t test. For behavioral testing, sample size (minimum n = 10/group) was calculated based on predicting detectable differences to reach power of 0.80 at a significance level of <0.05, assuming a 33% difference in mean and a 25% SD at the 95% confidence level. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc comparisons for (1) genotype and stroke effects or (2) genotype and treatment effects in Prism 6.0 software. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Enhanced locomotion and kinematic recovery in BDNFM/M mice

A total of 187 male BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M littermates (3–4 month of age) were used for the study. With preventative antibacterial treatment (Meisel et al., 2004) and intensive postischemic care for 7 d, the mortality rate among mice with successful MCAO was 18% (12 of 65) in BDNF+/+ and 28% (14 of 49) in BDNFM/M mice. There was no mortality in sham-operated mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weight, CBF, and breakdown of the number of mice in the study

| Sham |

Stroke |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF+/+ | BDNFM/M | BDNF+/+ | BDNFM/M | |

| Total number of animals | 31 | 20 | 72 | 64 |

| Body weight (g) | 26.07 ± 0.29 | 27.53 ± 0.70* | 27.57 ± 0.36 | 30.19 ± 0.80** |

| Failed MCAO | — | — | 7 | 15 |

| Successful MCAO | — | — | 65 | 49 |

| CBF reduction (%) | — | — | 85.47 ± 0.82 | 82.91 ± 1.33 |

| CBF reperfusion (%) | — | — | 129.0 ± 6.03 | 131.2 ± 7.58 |

| Death in postprocedure | 0 | 0 | 12 | 14 |

| Animals entered in study | 31 | 20 | 53 | 35 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

*p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01 versus BDNF+/+.

As reported previously (Chen et al., 2006), BDNFM/M mice were heavier than BDNF+/+ mice at the time of sham surgery or MCA occlusion (Table 1). In a subset of BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice, body weight was measured before and after stroke. In mice receiving the sham procedure, BDNFM/M mice gained their body weights significantly faster than BDNF+/+ mice at 2, 4, and 6 months (Table 2). However, the overall weight changes in poststroke mice were similar between the genotypes. Compared with preischemic baseline, body weights were similarly reduced at 5 d postischemia but returned to their baseline at ∼4 months in both genotypes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Longitudinal body weight measurement

| Sham |

Stroke |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF+/+ | BDNFM/M | BDNF+/+ | BDNFM/M | |

| Prior to stroke | 26.5 ± 1.4 | 29.5 ± 2.3 | 28.1 ± 2.6 | 31.7 ± 4.2* |

| 3 d | 25.9 ± 1.3 | 28.5 ± 2.8 | 22.2 ± 2.1 | 25.5 ± 4.2 |

| 5 d | 25.7 ± 1.2 | 28.5 ± 2.5 | 20.9 ± 2.1 | 24.3 ± 4.0 |

| 1 week | 25.8 ± 1.3 | 28.5 ± 2.4 | 21.4 ± 2.4 | 24.4 ± 3.9 |

| 2 weeks | 26.1 ± 1.3 | 30.1 ± 2.9 | 25.0 ± 1.9 | 27.5 ± 2.3 |

| 1 month | 26.4 ± 1.9 | 32.1 ± 3.3*** | 25.9 ± 2.0 | 29.3 ± 3.1 |

| 2 months | 29.1 ± 2.1 | 36.3 ± 5.2*** | 27.7 ± 2.1 | 31.4 ± 4.0 |

| 4 months | 33.2 ± 3.4 | 45.0 ± 7.4*** | 30.1 ± 2.6 | 35.5 ± 5.7*** |

| 6 months | 35.1 ± 3.7 | 48.7 ± 7.4*** | 30.5 ± 2.7 | 38.2 ± 6.9*** |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (grams). N = 12–18 for sham and 18–22 for stroke groups. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's tests.

*p < 0.05,

*** p < 0.001 versus BDNF+/+.

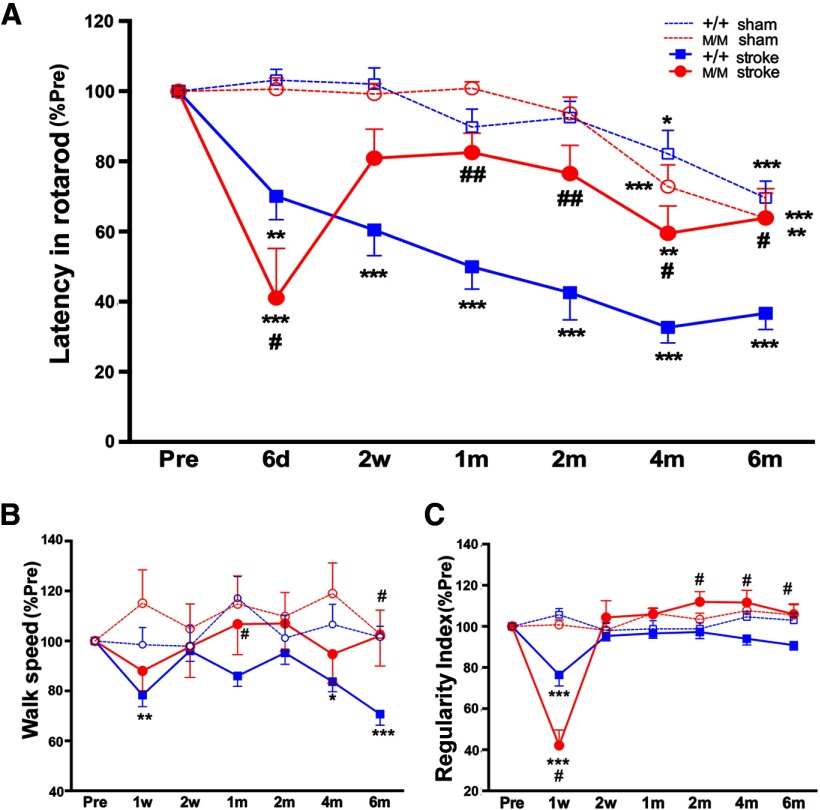

We assessed motor/gait function using a priori chosen behavior parameters in BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice during acute and recovery phases following stroke. Stroke-induced percentage changes were presented against their own preischemia baseline to account for interanimal variability. Both BDNF+/+-sham and BDNFM/M-sham mice showed a similar age-related decline in rotarod performance (Fig. 1A). Following stroke, BDNF+/+ mice showed progressive impairment in rotarod performance during 6 months of recovery. As previously reported (Qin et al., 2011), BDNFM/M-stroke mice displayed a greater acute impairment. However, the performance was markedly improved by 2 weeks. The Met-induced performance crossovers, typically occurring at 2–4 weeks poststroke, was followed by sustained enhancement during a recovery phase, reaching similar levels of performance as sham-operated mice at 6 months (Fig. 1A). This longitudinal rotarod performance demonstrates that the BDNF SNP caused greater impairment in an acute phase, accelerated recovery during a subacute period, and protection from age-related decline during a chronic recovery phase.

Figure 1.

Enhanced locomotion and kinematic recovery in BDNFM/M mice. Longitudinal behavior test in BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice during acute (d, days), subacute (w, weeks), and recovery (m, months) phases following stroke along with age-matched sham-operated mice. A, Rotarod performance, latency to fall measured in seconds. B, Walk speed, the average speed expressed in distance units per second. C, Regularity index, a parameter to gauge the degree of interlimb coordination. All results are presented as percentage of preischemic baseline (% Pre, mean ± SEM). +/+, BDNF+/+ mice; M/M, BDNFM/M mice; n = 12–16/group, two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's tests *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001 versus preischemic baseline (Pre), #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, +/+ stroke versus M/M stroke.

The restoration of walking is a high priority for people who have suffered a stroke (Harris and Eng, 2004). Thus, we selected parameters to assess speed and coordination of gait. There was no age-related decline in walk speed in sham-operated BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice (Fig. 1B). Walk speed was impaired in BDNF+/+-stroke mice at 1 week, returned to prestroke baseline at 2 weeks, and started to decline at 2 months. The sustained deficit in BDNF+/+-stroke mice during this late recovery phase reflected a stroke-induced behavioral deficit, as sham mice showed no age-related impairment at this time. In contrast, BDNFM/M-stroke mice maintained their walk speed similar to sham-operated mice throughout the postischemic period and were significantly better than BDNF+/+-stroke mice at 1 and 6 months. Regularity index, a degree of interlimb coordination during gait, showed impairment at 1 week in both BDNF+/+-stroke and BDNFM/M-stroke mice (Fig. 1C). Compared with the BDNF+/+-stroke mice, the regularity index of BDNFM/M-stroke mice was higher during 2–6 months of the recovery phase. The data suggest that the Met allele may be associated with overall enhancement of whole-body locomotion and kinematic recovery.

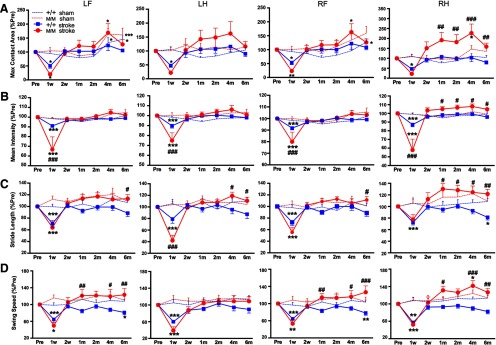

Gait kinematic analysis reveals compensation in BDNFM/M mice

Stroke causes hemiparesis, and we hypothesized that CatWalk gait analysis would reveal impairments in the LF and LH limbs after right MCAO. To test asymmetry, we assessed paw contact area, pressure exerted on the glass plate, stride length, and swing speed in LF, LH, RF, and RH limbs. Both BDNF+/+-sham and BDNFM/M-sham mice showed relatively constant maximum contacting area on the plate (Fig. 2A) or intensity, which is proportional to the weight supported on that paw (Fig. 2B). Following stroke, BDNF+/+ BDNFM/M mice showed acute impairment at 1 week in maximum contact area and mean intensity with greater impairments in BDNFM/M-stroke mice. BDNFM/M-stroke mice, however, displayed rapid improvement beyond preischemic baselines, and these overshoots were especially prominent in the ipsilesional RH limb (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2.

Enhanced gaits in the ipsilesional hindlimb in BDNFM/M mice. Longitudinal behavior test in BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice during 6 months poststroke along with age-matched sham-operated mice. A, Maximum contact area, the maximum area of a paw that comes into contact with the glass plate. B, Mean intensity, measure of pressure exerted on the glass plate. C, Stride length, distance between consecutive steps with the same paw. D, Swing speed, speed of the paw during swing. All results are presented as percentage of preischemic baseline (% Pre, mean ± SEM). +/+, BDNF+/+ mice; M/M, BDNFM/M mice. n = 12–16/group, two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's tests, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus preischemic baseline (Pre), #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, +/+ stroke versus M/M stroke. LF, left front; LH, left hind; RF, right front; RH, right hind limb.

Stride length measures distance between consecutive steps in the same paw. Sham mice, regardless of genotype, displayed relatively constant stride lengths in all four limbs over 6 months (Fig. 2C). Stroke shortened the stride length in both BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice, with spontaneous recovery at 2 weeks. Compared with BDNF+/+-stroke mice, BDNFM/M-stroke mice displayed significantly larger stride lengths at 6 months in all four limbs, and from 1 month on in the RH limb (Fig. 2C, right). Swing speed, computed from stride length over swing duration, is a parameter that assesses the temporal relation of gait. Although the parameter was relatively constant in all four limbs during 6 months in sham groups, stroke induced acute slowing in both genotypes (Fig. 2D). BDNF+/+ mice showed stroke-induced decline in the late recovery phase, but BDNFM/M mice showed significantly faster swing speed in LF, RF, and RH limbs that was most prominent at later time points (Fig. 2D). Since the mice underwent a unilateral stroke in the right hemisphere, the prominent enhancement in the ipsilesional RH limb suggests an involvement of the contralesional (left) hemisphere in behavioral enhancement in these BDNFM/M-stroke mice.

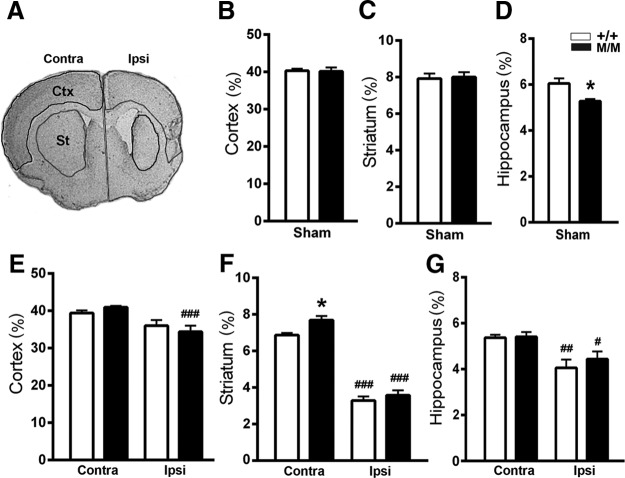

Larger contralesional striatum in BDNFM/M-stroke mice

To investigate whether the behavioral changes in BDNFM/M mice are associated with anatomical alterations, subregional volume was measured in the brains of BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice at 6 months poststroke. In age-matched sham animals, we found no difference between the genotypes in striatal and cortical volumes (Fig. 3B,C), but did find a previously reported volume reduction in the BDNFM/M hippocampus (Fig. 3D; Chen et al., 2006). Stroke reduced the ipsilesional hemispheric volume in both genotypes. The reduction was mainly due to decreased volume in the striatum (Fig. 3F) and, to a lesser extent, in the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 3E,G). Estimated infarct size at 6 months, obtained by subtracting the volume of the ipsilesional hemisphere from that of the contralesional hemisphere, was similar between the genotypes (percentage of contralesional volume, +/+ vs M/M, 14.2 ± 2.4, 15.7 ± 1.8, p = 0.62, n = 8/group), which is consistent with our previous report (Qin et al., 2011). The Met allele-associated behavioral enhancement was therefore unlikely due to the difference in infarct size.

Figure 3.

Larger striatal volume in the contralesional hemisphere of BDNFM/M-stroke mice. A, A representative Nissl-stained section at the level of striatum. B–G, Subregional volumes in age-matched sham (B–D) and in 6-month-poststroke (E–G) mice were determined from serially collected sections at a 600 μm interval for the cortex (B, E, +2.8 mm from bregma to −3.8 mm), striatum (C, F, +1.7 mm from bregma to −2.0 mm), and hippocampus (D, G, −0.9 mm from bregma to −3.8 mm). All results are presented as percentage (%) of contralesional hemisphere volume (mean ± SEM). BDNF+/+ (+/+) and BDNFM/M (M/M) mice. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's tests, *p < 0.05, +/+ versus M/M mice. n = 5 (sham) and 8 (stroke)/group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, versus corresponding contralesional hemisphere. Contra, Contralesional; Ipsi, ipsilesional; Ctx, cortex; St, striatum.

In the contralesional hemisphere, there was a selective increase in striatal volume in the BDNFM/M mice but the increases were not detected in the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 3E–G). Further comparison between stroke and age-matched sham mice showed that stroke reduced the contralesional striatal volume in BDNF+/+ mice (sham vs stroke, 7.92 ± 0.28% vs 6.87 ± 0.12%, n = 5–8, p < 0.05) but not in BDNFM/M mice (sham vs stroke, 8.00 ± 0.27 vs 7.69 ± 0.27, n = 5–8, ns). This suggests that BDNFM/M mice are either resistant to stroke-induced atrophy or prone to hypertrophy in the contralesional striatum. The selective anatomical changes in the contralesional (left) striatum in BDNFM/M mice raised the intriguing possibility of the involvement of this structure in controlling motor recovery through the ipsilesional (RH) limb.

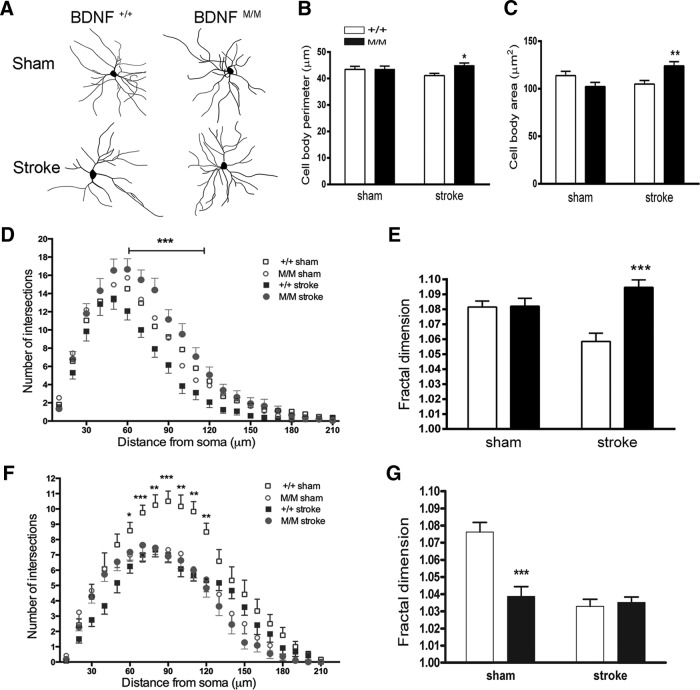

Morphological changes in striatal neurons in BDNFM/M-stroke mice

To evaluate the cellular basis of the Met allele-induced structural plasticity, we assessed the morphology of medium spiny neurons (MSNs), a major type of neurons, in the contralesional striatum 6 months after stroke (Fig. 4A). MSN sizes, indicated by soma perimeters and areas, were similar between BDNF+/+-sham and BDNFM/M-sham mice. Following stroke, BDNFM/M mice exhibited increased cell body perimeter and area (Fig. 4B,C). While dendritic arbor in MSNs were similar between genotypes in sham mice, those of BDNFM/M-stroke mice were much more complex at 60–120 μm distance from soma (Fig. 4D). This was accompanied by increased branching that fills neuronal fields (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Morphological changes in striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in BDNFM/M-stroke mice. A–E, Neurons were obtained from the contralesional hemisphere in BDNF+/+ (+/+) and BDNFM/M (M/M) mice 6 months after stroke and in age-matched sham mice. Morphological analyses of MSNs in the striatum. A, Representative tracing of Golgi-stained MSNs in the contralesional striatum. B–E, Assessment of striatal MSN size by determining perimeter of cell soma (B), area of MSN soma (C), Sholl analysis to determine dendritic arbor (D), and fractal dimension for complexity index (E). F, G, Morphological analyses of hippocampal neurons for dendritic arbor (F) and fractal dimension for complexity index (G). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, BDNF+/+-stroke versus BDNFM/M-stroke mice. n = 5–6 mice/group (4–5 neurons from each mouse, total 25 neurons).

The hippocampus is another structure that showed the Met-associated volume change in control mice (Fig. 3D). We therefore analyzed the morphology of the neurons in the hippocampus to confirm the observed anatomical and cell biological effects of the BDNF SNP. We found that the reduced hippocampal volume in BDNFM/M-sham mice (Fig. 3D) was accompanied by less dendritic arborization and complexity in the hippocampal neurons compared with BDNF+/+-sham mice (Fig. 4F,G), confirming the anatomical and morphological link. Neurons from the contralesional hippocampus showed no differences in poststroke dendritic arborization and complexity between the genotypes (Fig. 4F,G). Lack of stroke-induced morphological changes in the contralesional hippocampal neurons suggests that the striatum, rather than the hippocampus, is involved in stroke recovery.

Elevated excitatory synaptic markers in the contralesional striatum of BDNFM/M mice

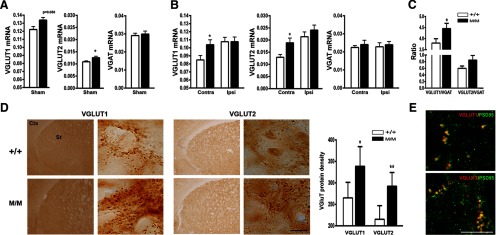

The striatum largely receives excitatory afferents from the cortex and thalamus. Because the transition from inhibition to excitation has been associated with behavior improvement (Dang et al., 2006; Clarkson et al., 2010), we hypothesized that the Met-induced behavioral enhancement is associated with elevated expression of excitatory markers in the contralesional striatum. In sham mice, BDNFM/M mice exhibited higher mRNA levels of the excitatory synapse components VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 5A). mRNA levels of inhibitory synaptic marker VGAT were not different between the genotypes. The selective increase of VGLUT1/2 in the BDNFM/M sham mice suggests that increased expression of excitatory markers may be an intrinsic feature of BDNFM/M mice. Following stroke, BDNFM/M mice exhibited higher VGLUT1/2 mRNA levels in the contralesional hemisphere while there were no differences in the ipsilesional hemisphere (Fig. 5B). There were no differences in VGAT expression between the genotypes in both hemispheres. The ratio of VGLUT1/2 mRNA expression over VGAT in the contralesional hemisphere was higher in BDNFM/M mice (Fig. 5C). Immunolocalization of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 proteins in the contralesional striatum showed more abundant and intense VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 immunoreactivity in the contralesional striatum of BDNFM/M mice (Fig. 5D). Confocal images from BDNFM/M mice showed close physical proximity of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 presynaptic proteins with PSD-95, an excitatory postsynaptic marker, indicating that the expression of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 occurs at the level of synapse (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Enhanced excitatory synaptic markers in the contralesional striatum of BDNFM/M mice. A, Gene expression of excitatory (VGLUT1 and VGLUT2) and inhibitory (VGAT) synaptic marker in age-matched sham BDNF+/+ (+/+) and BDNFM/M (M/M) mice. B, Gene expression of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic markers in the contralesional (contra) and ipsilesional (ipsi) hemispheres 6 months postischemia. C, Ratios of excitatory over inhibitory marker expression in the contralesional hemisphere of 6-month-postischemic BDNF SNP mice. n = 5 (sham) and 8 (stroke)/group. D, VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 protein expression in the contralesional striatum and quantification. Densities were presented as number of immunopositive dots per framed area (0.1 mm2), n = 4–5 mice/groups. E, Confocal images from the contralesional striatum of 6-month-poststroke M/M mice showing close proximity of VGLUT1/2 with PSD-95, an excitatory postsynaptic marker. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, +/+ versus M/M mice. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Greater reliance on the contralesional striatum of BDNFM/M mice for recovery

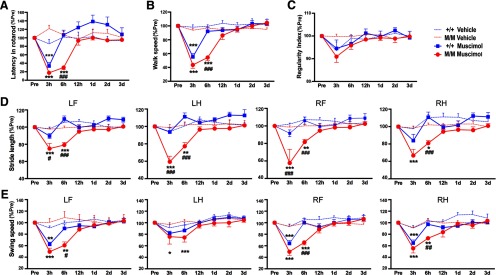

Pharmacological inactivation is an effective and reversible tool for defining the functional contributions of cortical and subcortical control of movement (Martin and Ghez, 1999). To address the importance of the striatum in motor function, we administered muscimol, a GABA receptor agonist, into the contralesional striatum to transiently inactivate the structure 1 month after stroke, when BDNFM/M mice outperform BDNF+/+ mice (Fig. 1). There was no noticeable change from baseline rotarod performance in saline-treated BDNF+/+ and BDNFM/M mice (Fig. 6A). In both genotypes, muscimol acutely impaired rotarod performance, which was recovered by 12 h following administration; the severity and duration of the deficits were greater in BDNFM/M mice, with a significant genotype difference at 6 h (Fig. 6A). Muscimol also caused transient impairment of walk speed in both genotypes (Fig. 6B). Similar to rotarod performance, the deficit in walk speed was also larger in BDNFM/M mice. Regularity index was not affected by muscimol in either genotype (Fig. 6C). In individual limb assessment, we found that muscimol treatment minimally affected maximum contact area and mean intensity in all four limbs (data not shown). However, the treatment caused transient impairment in stride length and swing speed in all four limbs, and the deficits were greater in BDNFM/M mice (Fig. 6D,E). The larger and longer deficits in muscimol-treated BDNFM/M mice indicate a greater dependence on the contralesional striatum for functional recovery in Met homozygotes.

Figure 6.

Greater reliance on the contralesional striatum of BDNFM/M mice for recovery. Assessment of acute motor/gait function following vehicle or muscimol injection in the contralesional striatum of 1-month-postischemic BDNF+/+ (+/+) and BDNFM/M (M/M) mice. A, Rotarod performance, latency to fall, measured in seconds. B, Walk speed, the average speed expressed in distance units per second. C, Regularity index, parameter to gauge the degree of interlimb coordination. D, Stride length, distance between consecutive steps with the same paw. E, Swing speed, speed of the paw during swing. The behavior before treatment was used as a baseline. All results are presented as percentage of preischemic baseline (% Pre, mean ± SEM). n = 10/group. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's tests, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 muscimol versus vehicle; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 +/+ versus M/M. LF, left front; LH, left hind; RF, right front; RH, right hind limb.

Discussion

Structural plasticity and behavioral adaptation occur for an extended period following stroke. This study addressed the specific genetic influence of a human SNP at codon 66 (Val66Met) of the BDNF gene in chronic stroke. Our major finding is that the mice expressing the BDNF Met allele unexpectedly displayed enhanced motor recovery after chronic stroke compared with the genetic background-matched and age-matched mice expressing the wild-type BDNF alleles. The Met allele-associated enhancement selectively involves the contralesional striatum, which showed structural and synaptic plasticity after stroke not observed in other regions. This was accompanied by the enhanced gait in ipsilesional hindlimb and overall improvement of motor and kinematic recovery. Despite the predicted negative influence of the Met allele in motor system function and experience-dependent plasticity (Egan et al., 2003; Kleim et al., 2006; McHughen et al., 2010), this study highlights a selective advantage to carrying the common human BDNF SNP in motor recovery in chronic stroke. While the severity of tissue damage influences the extent of injury-induced plasticity (Frost et al., 2003), lack of difference in infarct size between the genotypes (Qin et al., 2011) suggests a true genetic influence of BDNF SNP on injury-induced structural plasticity and behavioral adaptation.

Anatomical and structural plasticity in the noninjured hemisphere

Compared to wild-type mice, BDNFM/M mice were previously shown to have anatomical and morphological differences at baseline that were associated with cognitive deficits and anxiety related behavior (Chen et al., 2006). Here we report differences in function that emerged only after injury. An issue regarding the surprising enhancements in motor function in Met homozygotes is whether they are an unexpected consequence of established phenotypic differences or whether they represent a newly defined advantage of carrying two Met alleles postinjury. Our findings suggest that the BDNFM/M genotype confers a functional benefit involving the contralesional striatum. While ischemic stroke at the proximal MCA largely affects the ipsilesional striatum, clinical studies suggested an involvement of the noninjured hemisphere in behavioral improvement in human patients with subcortical stroke (Calautti et al., 2001; Gerloff et al., 2006). Congruent with these reports, we found selective increase in striatal volume in the hemisphere contralesional to stroke (Fig. 3) and enhanced neuronal dendritic arbors and complexity in the neurons from this subregion (Fig. 4). Thus, the plasticity in the contralesional striatum may drive the enhancement of functional recovery in the mice carrying the Met allele.

Adaptive role of the Met allele

Synaptic balance between excitation and inhibition is critical for processing sensory information, motor activity, and cognitive function (Brown et al., 1996; Cline, 2005). Structural and synaptic adaptation following striatal injury is likely to occur through complex basal ganglia–cortical circuits. Primary inputs to the striatum are excitatory afferents from the cortex and thalamus, which then project inhibitory efferents to the globus pallidus (GP) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) involving direct and indirect pathways. The pathways project back to the thalamus and cortex to complete the striato-thalamic-cortical circuits (Kreitzer and Malenka, 2008; Kozorovitskiy et al., 2012). The net effect of the direct and indirect pathways is respective facilitation and inhibition of movement. Thus, a potential shift to excitation in the BDNFM/M striatum, probably resulting from disinhibition of inhibitory inputs to the thalamus through GP and SNr, may accentuate excitatory cortical afferents to the striatum. The inferred excitation may be particularly relevant to the mechanism of reorganization and behavioral improvement. Mice lacking the NMDAR1 subunit in the striatum showed disrupted motor learning and synaptic plasticity (Dang et al., 2006). In stroke, reduced excessive GABAergic tonic inhibition (disinhibition, thereby net result of excitation) or activation of AMPA receptors promoted functional recovery (Clarkson et al., 2010, 2011). Additionally, reduction of the inhibitory markers in the perilesional area is necessary for reorganization and mediates stroke recovery (Zeiler et al., 2013). A shift of network balance to excitation may be an intrinsic feature of the Met allele because BDNFM/M-sham mice also exhibited increased excitatory synaptic markers in the brain (Fig. 5A). In light of the finding that excitation is functionally beneficial (Clarkson et al., 2010), the working model is that Met-induced excitation bias in the contralesional striatum drives recovery in the chronic phase of stroke recovery in Met homozygotes through a compensatory effect on the contralesional hindlimb. The larger reversible impairment of motor and gait functions in Met homozygotes by muscimol suggests a potential Met-induced shift to excitation and the importance of the contralesional striatum on behavioral adaptation in chronic stroke.

Despite histological evidence that the lesion in the MCAO model is restricted to the side of occlusion, gait analysis revealed acute gait impairments in the limbs of both sides (Fig. 2). Similarly, the bilateral deficits were also evident upon unilateral inactivation of the contralesional striatum by muscimol (Fig. 6). Dozens of studies have documented this phenomenon in both rodents and humans (Pandian and Arya, 2013; Darling et al., 2011; Schaefer et al., 2009). Following stroke, patients often experience loss in strength and speed of movement in the ipsilesional arm. Similarly, acute impairments in the ipsilesional forelimb were described in rodents, indicating that the ipsilesional side was not “nonaffected” but rather “less affected.” While the mechanism that accounts for the acute bilateral deficits is not clear, underlying events may involve plastic changes in the intact hemisphere and disturbed interhemispheric connectivity due to the ongoing infarction in the affected hemisphere (Gonzalez et al., 2004; van Meer et al., 2010).

Clinical relevance

Limitations of the present findings include the undetermined relevance of improving motor function of unaffected limbs in quadruped rodents to humans. However, the organization of the lumbar central pattern generator between rodents and humans is comparable, and these circuits are controlled by similar supraspinal mechanisms (Rossignol, 2006; Gerasimenko et al., 2008). Thus, this study could provide insights into the genetic component of human locomotor/kinematic recovery following stroke. An additional caveat is that BDNFM/M mice often overshoot beyond preischemic baselines. The functional significance of this compensatory plasticity is unclear as it could reflect adaptive or maladaptive responses. However, the association between the overshoots and better, faster, and larger gait throughout the recovery phase suggests they are adaptive compensations necessary for regaining motor control.

Interruption of blood flow in MCA is a common cause of cerebral infarction involving basal ganglia. The size of the basal ganglia in the rodent brain, as a proportion of total brain volume, is approximately twice that of the human basal ganglia (Swanson, 1995). Therefore, a 20% subcortical infarct in the rodents may ∼10% subcortical infarct in human when anatomical proportions between the species are considered. Because infarct size in lacunar stroke, a common type of stroke in human with pure motor hemiparesis with good recovery (Bamford et al., 1987; Longstreth et al., 1998; Bejot et al., 2008), typically ranges from 4.5 to 14% of a hemisphere (Carmichael, 2005), the infarct size in the current mouse stroke model would be relevant to human subcortical stroke.

In summary, the key mechanisms stipulated here include the BDNF SNP-induced behavioral changes at the system level resulting from compensation in the nonstroked side, structural changes in the noninjured hemisphere, and cellular changes associated with structural/synaptic plasticity. The mechanistic insights into the differences between known BDNF polymorphisms would be valuable in predicting the course of stroke recovery based on an individual's BDNF SNP. Additionally, the Met allele-induced biphasic profile, greater acute deficits followed by enhanced recovery, provides potential windows for manipulating synaptic balance in chronic stroke. Strategies aimed at reducing acute excitation in Met carriers and/or enhancing delayed excitation for the subjects with the Val allele may provide an individual's BDNF SNP-based therapy. Testing the concept of Met allele-induced plasticity and behavior adaptation in stroke models that affect other areas of the brain is warranted.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers UL1RR024996 (to S.C. and F.L.), NS077897 and HL082511 (to S.C.), and NS073796 (to J.C.), Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Foundation (to R.R.), and the Burke Foundation (to S.C.). We thank C. Beltran and S. Bhosle for technical assistance and Dr. E. Shipp and N. Geibel for editorial assistance.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Bamford J, Sandercock P, Jones L, Warlow C. The natural history of lacunar infarction: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1987;18:545–551. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.18.3.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateup HS, Santini E, Shen W, Birnbaum S, Valjent E, Surmeier DJ, Fisone G, Nestler EJ, Greengard P. Distinct subclasses of medium spiny neurons differentially regulate striatal motor behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14845–14850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009874107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejot Y, Catteau A, Caillier M, Rouaud O, Durier J, Marie C, Di Carlo A, Osseby GV, Moreau T, Giroud M. Trends in incidence, risk factors, and survival in symptomatic lacunar stroke in Dijon, France, from 1989 to 2006: a population-based study. Stroke. 2008;39:1945–1951. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Ridding MC, Werhahn KJ, Rothwell JC, Marsden CD. Abnormalities of the balance between inhibition and excitation in the motor cortex of patients with cortical myoclonus. Brain. 1996;119:309–317. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calautti C, Leroy F, Guincestre JY, Baron JC. Dynamics of motor network overactivation after striatocapsular stroke: a longitudinal PET study using a fixed-performance paradigm. Stroke. 2001;32:2534–2542. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.097401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST. Rodent models of focal stroke: size, mechanism, and purpose. NeuroRx. 2005;2:396–409. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of neural repair after stroke: making waves. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:735–742. doi: 10.1002/ana.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ, Herrera DG, Toth M, Yang C, McEwen BS, Hempstead BL, Lee FS. Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior. Science. 2006;314:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.1129663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Park EM, Febbraio M, Anrather J, Park L, Racchumi G, Silverstein RL, Iadecola C. The class B scavenger receptor CD36 mediates free radical production and tissue injury in cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2504–2512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0035-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson AN, Huang BS, Macisaac SE, Mody I, Carmichael ST. Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature. 2010;468:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature09511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson AN, Overman JJ, Zhong S, Mueller R, Lynch G, Carmichael ST. AMPA receptor-induced local brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling mediates motor recovery after stroke. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3766–3775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5780-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline H. Synaptogenesis: a balancing act between excitation and inhibition. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R203–R205. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC. Repairing the human brain after stroke: I. Mechanisms of spontaneous recovery. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:272–287. doi: 10.1002/ana.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Yin HH, Lovinger DM, Wang Y, Li Y. Disrupted motor learning and long-term synaptic plasticity in mice lacking NMDAR1 in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15254–15259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601758103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling WG, Pizzimenti MA, Hynes SM, Rotella DL, Headley G, Ge J, Stilwell-Morecraft KS, McNeal DW, Solon-Cline KM, Morecraft RJ. Volumetric effects of motor cortex injury on recovery of ipsilesional dexterous movements. Exp Neurol. 2011;231:56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, Zaitsev E, Gold B, Goldman D, Dean M, Lu B, Weinberger DR. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112:257–269. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SB, Barbay S, Friel KM, Plautz EJ, Nudo RJ. Reorganization of remote cortical regions after ischemic brain injury: a potential substrate for stroke recovery. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:3205–3214. doi: 10.1152/jn.01143.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko Y, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Epidural stimulation: comparison of the spinal circuits that generate and control locomotion in rats, cats and humans. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff C, Bushara K, Sailer A, Wassermann EM, Chen R, Matsuoka T, Waldvogel D, Wittenberg GF, Ishii K, Cohen LG, Hallett M. Multimodal imaging of brain reorganization in motor areas of the contralesional hemisphere of well recovered patients after capsular stroke. Brain. 2006;129:791–808. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez CL, Gharbawie OA, Williams PT, Kleim JA, Kolb B, Whishaw IQ. Evidence for bilateral control of skilled movements: ipsilateral skilled forelimb reaching deficits and functional recovery in rats follow motor cortex and lateral frontal cortex lesions. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:3442–3452. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers FP, Koopmans GC, Joosten EA. CatWalk-assisted gait analysis in the assessment of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:537–548. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JE, Eng JJ. Goal priorities identified through client-centred measurement in individuals with chronic stroke. Physiother Can. 2004;56:171–176. doi: 10.2310/6640.2004.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XM, Zhang ZX, Zhang JW, Zhou YT, Tang MN, Wu CB, Hong Z. Lack of association between the BDNF gene Val66Met polymorphism and Alzheimer disease in a Chinese Han population. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;55:151–155. doi: 10.1159/000106473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong EJ, McCord AE, Greenberg ME. A biological function for the neuronal activity-dependent component of Bdnf transcription in the development of cortical inhibition. Neuron. 2008;60:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermani P, Rafii D, Jin DK, Whitlock P, Schaffer W, Chiang A, Vincent L, Friedrich M, Shido K, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Rafii S, Hempstead BL. Neurotrophins promote revascularization by local recruitment of TrkB+ endothelial cells and systemic mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:653–663. doi: 10.1172/JCI22655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Tolhurst AT, Qin LY, Chen XY, Febbraio M, Cho S. CD36/fatty acid translocase, an inflammatory mediator, is involved in hyperlipidemia-induced exacerbation in ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4661–4670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0982-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Chan S, Pringle E, Schallert K, Procaccio V, Jimenez R, Cramer SC. BDNF val66met polymorphism is associated with modified experience-dependent plasticity in human motor cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:735–737. doi: 10.1038/nn1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Ogier M, Kunze DL, Katz DM. Exogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic dysfunction in Mecp2-null mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5303–5310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5503-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozorovitskiy Y, Saunders A, Johnson CA, Lowell BB, Sabatini BL. Recurrent network activity drives striatal synaptogenesis. Nature. 2012;485:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature11052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Striatal plasticity and basal ganglia circuit function. Neuron. 2008;60:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger F, Pardini M, Huey ED, Raymont V, Solomon J, Lipsky RH, Hodgkinson CA, Goldman D, Grafman J. The role of the Met66 brain-derived neurotrophic factor allele in the recovery of executive functioning after combat-related traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:598–606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1399-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth WT, Jr, Bernick C, Manolio TA, Bryan N, Jungreis CA, Price TR. Lacunar infarcts defined by magnetic resonance imaging of 3660 elderly people: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1217–1225. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH, Ghez C. Pharmacological inactivation in the analysis of the central control of movement. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;86:145–159. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(98)00163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHughen SA, Rodriguez PF, Kleim JA, Kleim ED, Marchal Crespo L, Procaccio V, Cramer SC. BDNF val66met polymorphism influences motor system function in the human brain. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:1254–1262. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel C, Prass K, Braun J, Victorov I, Wolf T, Megow D, Halle E, Volk HD, Dirnagl U, Meisel A. Preventive antibacterial treatment improves the general medical and neurological outcome in a mouse model of stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000109041.89959.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowska-Guzel D, Gromadzka G, Czlonkowski A, Czlonkowska A. BDNF −270 C>T polymorphisms might be associated with stroke type and BDNF −196 G>A corresponds to early neurological deficit in hemorrhagic stroke. J Neuroimmunol. 2012;249:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Wang Y, Kim S, Hong SM, Jeng L, Bilgen M, Liu J. Assessing gait impairment following experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;176:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudo RJ. Postinfarct cortical plasticity and behavioral recovery. Stroke. 2007;38:840–845. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000247943.12887.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandian S, Arya KN. Motor impairment of the ipsilesional body side in poststroke subjects. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013;17:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo MM. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:24–32. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Kim E, Ratan R, Lee FS, Cho S. Genetic variant of BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism attenuates stroke-induced angiogenic responses by enhancing anti-angiogenic mediator CD36 expression. J Neurosci. 2011;31:775–783. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4547-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol S. Plasticity of connections underlying locomotor recovery after central and/or peripheral lesions in the adult mammals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1647–1671. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SY, Haaland KY, Sainburg RL. Hemispheric specialization and functional impact of ipsilesional deficits in movement coordination and accuracy. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2953–2966. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seil FJ, Drake-Baumann R. TrkB receptor ligands promote activity-dependent inhibitory synaptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5367–5373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05367.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Nesse RM, Stoltenberg SF, Li S, Gleiberman L, Chakravarti A, Weder AB, Burmeister M. A BDNF coding variant is associated with the NEO personality inventory domain neuroticism, a risk factor for depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:397–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siironen J, Juvela S, Kanarek K, Vilkki J, Hernesniemi J, Lappalainen J. The Met allele of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predicts poor outcome among survivors of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007;38:2858–2860. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.485441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Gabriel SB, McInnis MG, Bennett P, Lim Y, Tsan G, Schaffner S, Kirov G, Jones I, Owen M, Craddock N, DePaulo JR, Lander ES. Family-based association study of 76 candidate genes in bipolar disorder: BDNF is a potential risk locus. Brain-derived neutrophic factor. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:579–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. Mapping the human brain: past, present, and future. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:471–474. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)92766-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer MP, van der Marel K, Wang K, Otte WM, El Bouazati S, Roeling TA, Viergever MA, Berkelbach van der Sprenkel JW, Dijkhuizen RM. Recovery of sensorimotor function after experimental stroke correlates with restoration of resting-state interhemispheric functional connectivity. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3964–3972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5709-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilkki J, Lappalainen J, Juvela S, Kanarek K, Hernesniemi JA, Siironen J. Relationship of the Met allele of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism to memory after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:198–203. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000320382.21577.8E. discussion 203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N, Wagner KD, Theres H, Englert C, Schedl A, Scholz H. Coronary vessel development requires activation of the TrkB neurotrophin receptor by the Wilms' tumor transcription factor Wt1. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2631–2642. doi: 10.1101/gad.346405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Hayden MR, Xu B. BDNF overexpression in the forebrain rescues Huntington's disease phenotypes in YAC128 mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14708–14718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1637-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler SR, Gibson EM, Hoesch RE, Li MY, Worley PF, O'Brien RJ, Krakauer JW. Medial premotor cortex shows a reduction in inhibitory markers and mediates recovery in a mouse model of focal stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:483–489. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.676940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Peng Q, Li Q, Jahanshad N, Hou Z, Jiang M, Masuda N, Langbehn DR, Miller MI, Mori S, Ross CA, Duan W. Longitudinal characterization of brain atrophy of a Huntington's disease mouse model by automated morphological analyses of magnetic resonance images. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2340–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]