Abstract

AIM: To investigate whether proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pretreatment influences Helicobacter pylori eradication rate.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed H. pylori-infected patients who were treated with a standard triple regimen (PPI, amoxicillin 1 g, and clarithromycin 500 mg, all twice daily for 7 d). The diagnosis of H. pylori infection and its eradication was assessed with the rapid urease test, histological examination by silver staining, or the 13C-urea breath test. We divided the patients into two groups: one received the standard eradication regimen without PPI pretreatment (Group A), and the other received PPI pretreatment (Group B). The patients in Group B were reclassified into three groups based on the duration of PPI pretreatment: Group B-I (3-14 d), Group B-II (15-55 d), and Group B-III (≥ 56 d).

RESULTS: A total of 1090 patients were analyzed and the overall eradication rate was 80.9%. The cure rate in Group B (81.2%, 420/517) was not significantly different from that in Group A (79.2%, 454/573). The eradication rates in Group B-I, B-II and B-III were 80.1% (117/146), 81.8% (224/274) and 81.4% (79/97), respectively.

CONCLUSION: PPI pretreatment did not affect H. pylori eradication rate, regardless of the medication period.

Keywords: Proton pump inhibitor, Helicobacter pylori, Urea breath test, Antibiotics, Drug resistance

Core tip: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used for long periods. It is important to know whether long-term PPI pretreatment can influence Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication rates. There have been debates about the effect of PPI pretreatment on H. pylori eradication rate, although most previous studies have focused on the relatively short-term use of PPI. Our study investigated the impact of PPI pretreatment on H. pylori eradication rates based on different periods of treatment, including long-term pretreatment. Our data showed that PPI pretreatment did not affect H. pylori eradication rates, regardless of the medication period.

INTRODUCTION

Several guidelines recommend standard triple therapy consisting of two antimicrobial agents, such as amoxicillin with clarithromycin or metronidazole, and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) as the first choice treatment for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection[1-3]. The addition of a PPI to an antibiotic-containing regimen is known to boost the H. pylori eradication rate[4]. By increasing the intragastric pH, PPIs lower minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values and improve the chemical stability of antibacterial agents[5-7].

Although the inclusion of PPIs in the eradication regimen has been proven to be beneficial for curing H. pylori infection, it is still controversial whether PPI pretreatment influences the eradication rate. There was a recent study which showed that increasing the intragastric pH level by PPI pretreatment might improve the efficacy of H. pylori eradication[7]. Meanwhile, meta-analysis demonstrated that PPI pretreatment did not have any beneficial effect on H. pylori eradication[8]. Furthermore, some studies reported that PPI treatment before administering a single antibacterial agent, such as amoxicillin, decreases the eradication rate[9-11]. These findings have been explained by the fact that pretreatment induced the transition of H. pylori into coccoid dormant forms that are less vulnerable to the actions of antibiotics[12,13].

At present, endoscopic resection has been extensively applied to treat gastric neoplasms as a curative modality. This procedure inevitably results in a large iatrogenic ulcer, which subsequently poses the risk of gastric bleeding or perforation. To prevent these complications, PPIs are generally administered for > 4 wk[14,15]. However, recently there have been concerns raised about the possible adverse effects of long-term PPI treatment, including nutritional deficiencies, cardiovascular risk with PPI/clopidogrel co-prescriptions, and bone fractures[16,17]. Long-term PPI therapy should be used only in robust indications, and careful assessment of the risks and benefits is required.

In many cases, patients who received endoscopic resection with long-term PPI treatment need H. pylori eradication therapy because of its prophylactic effect on the development of metachronous gastric cancer[18-20]. From a clinical point of view, it is important to know whether long-term PPI pretreatment influences the H. pylori eradication rate. Previous studies have mostly focused on the effect of short-term PPI on H. pylori eradication, therefore, the effect of long-term PPI pretreatment is not yet clear. Our study was conducted to investigate the impact of PPI pretreatment on H. pylori eradication based on different periods of treatment duration, including long-term pretreatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed H. pylori-infected patients who were treated with a standard triple regimen from September 2009 to December 2011. The regimen consisted of PPI (lansoprazole 30 mg, esomeprazole 40 mg, or rabeprazole 20 mg), amoxicillin 1 g, and clarithromycin 500 mg, all twice daily for 7 d. Patients who completed the treatment and the assessment of eradication were enrolled in the study. Consumption of > 90% of the prescribed drugs was defined as good compliance and was accepted as the completion of treatment. The enrolled patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before eradication treatment. The exclusion criteria were previous eradication therapy (n = 11), use of H2 receptor antagonists or antibiotics within the past 4 wk (n = 58), being < 18 years (n = 3), and having an unknown history of recent medication (n = 35).

Assessment of H. pylori status

H. pylori infection was diagnosed according to one of the following tests: (1) rapid urease test (CLO test; Ballard Medical Products, Draper, UT, United States) by gastric mucosal biopsy from the body at the gastric angularis and greater curvature of the antrum; (2) histological examination by Warthin-Starry silver staining; and (3) 13C-urea breath test (Helifinder; Medichems, Seoul, South Korea). The assessment of eradication was performed at least 4 wk after the completion of 1 wk of the standard regimen. The 13C-urea breath test was generally used for the assessment of eradication, and rapid urease tests and histological examination were only used if repeat endoscopy was clinically indicated for other reasons.

Study design

We divided the patients into two groups: one received the standard eradication regimen without PPI pretreatment (Group A), and the other received the regimen with PPI pretreatment (Group B). PPI pretreatment in this study implied an intake of daily PPI (lansoprazole, rabeprazole, esomeprazole, or omeprazole) for ≥ 3 d before eradication therapy. Patients who received the eradication regimen within 3 d after the cessation of PPI pretreatment were enrolled in Group B, and those who received > 3 d were assigned to Group A. The rationale of these criteria was based on previous studies that demonstrated that the maximum effect of PPIs on the intragastric pH level occurred at least 3 d after the start of intake, and that the intragastric pH returned to the normal baseline level by 4 d after the cessation of PPI treatment[21,22]. Patients in Group B were reclassified into three groups based on the duration of PPI pretreatment: Group B-I (3-14 d), Group B-II (15-55 d), and Group B-III (≥ 56 d). We also collected data from medical charts including demographic characteristics, diagnosis, types of PPI used in the pretreatment or eradication regimen, and eradication assessment methods. These factors might be potentially associated with eradication rate, thus, they were applied for adjustment.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD, and categorical data are presented as quantities and proportions. A χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical data and the two-sample independent t test was used to analyze continuous data. Eradication rates were also investigated using adjusted logistic regression analysis. The analysis was performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States), and statistical significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

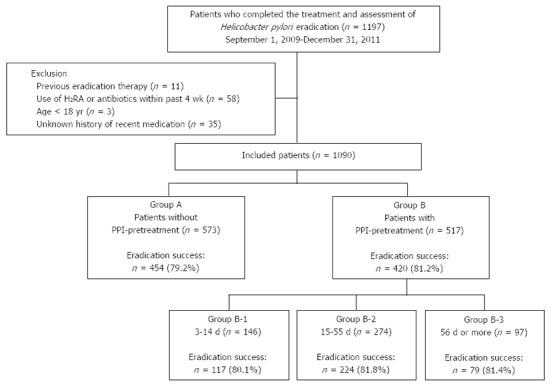

After excluding 107 individuals from a total of 1197 patients enrolled in this study, we finally analyzed 1090 patients including 138 with iatrogenic ulcers caused by the endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms. The retrospective assessment flow is presented in Figure 1. The mean age of the study group was 51.5 ± 12.8 years and 63.7% were male. The overall eradication rate was 80.2%.

Figure 1.

Flow of the study. A total of 1197 patients were investigated in the study period, and 573 patients in Group A [without proton pump inhibitors (PPI) pretreatment] and 517 in Group B (with PPI pretreatment) were included in the analysis. Patients in Group B were reclassified into three groups based on the duration of PPI pretreatment: Group B-1 (3-14 d), Group B-2 (15-55 d) and Group B-3 (≥ 56 d). H2RA: H2 receptor antagonist.

Among the analyzed patients, 573 were enrolled in Group A and 517 in Group B. The baseline characteristics of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. The cure rate in Group B (81.2%, 420/517) was not significantly different from that in Group A (79.2%, 454/573, P = NS). In addition, the eradication rates were also not significantly different between Group A and B in any diagnostic subgroup; 87.1% (27/31) vs 76.6% (82/107) for iatrogenic ulcers, 77.6% (340/438) vs 82.3% (325/395) for peptic ulcer, and 83.7% (87/104) vs 86.7% (13/15) for non-ulcer disease (all P = NS). PPI pretreatment did not affect the eradication rate even after adjusting for age, sex, diagnosis, type of PPI in the eradication regimen, and eradication assessment methods (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-1.58).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and eradication rates of the two groups n (%)

| Group Awithout PPI pretreatment(n = 573) | Group Bwith PPI pretreatment(n = 517) | P value | ||

| Age | mean ± SD (yr) | 51.8 ± 12.2 | 51.2 ± 13.4 | 0.453 |

| Sex | Male | 343 (59.9) | 351 (67.9) | 0.007 |

| Diagnosis | Iatrogenic ulcer | 31 (5.4) | 107 (20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer | 438 (76.4) | 395 (77.1) | ||

| Non-ulcer disease | 104 (18.2) | 15 (2.9) | ||

| PPI in the eradication regimen | Lansoprazole 30 mg | 439 (76.6) | 410 (79.3) | 0.021 |

| Esomeprazole 40 mg | 92 (16.1) | 56 (10.8) | ||

| Rabeprazole 20 mg | 42 (7.3) | 51 (9.9) | ||

| Eradication assessment method | 13C-urea breath test | 525 (91.6) | 408 (78.9) | < 0.001 |

| Rapid urease test | 37 (6.5) | 106 (20.5) | ||

| Histological examination | 11 (1.9) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Eradication rate | 454 (79.2) | 420 (81.2) | 0.407 | |

PPI: Proton pump inhibitors.

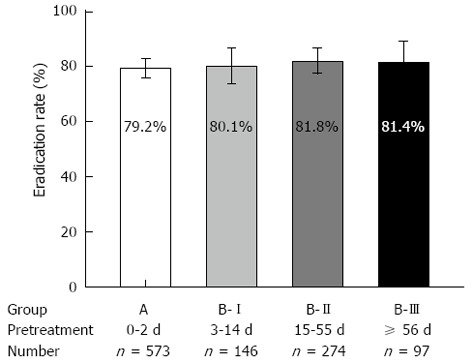

The types of PPI for the pretreatment therapy in Group B-I, B-II and B-III are shown in Table 2. The eradication rates in these three groups were 80.1% (117/146), 81.8% (224/274) and 81.4% (79/97), respectively. The eradication rates were not significantly different among these groups and Group A (P = NS; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Types of proton pump inhibitors used in the pretreatment in Group B n (%)

| Group B-I3-14 d (n = 146) | Group B-II15-55 d (n = 274) | Group B-III≥ 56 d (n = 97) | P value1 | |

| Lansoprazole | 80 (54.8) | 174 (63.5) | 62 (63.9) | 0.294 |

| Rabeprazole | 56 (38.4) | 82 (29.9) | 29 (29.9) | |

| Esomeprazole | 8 (5.5) | 17 (6.2) | 4 (4.1) | |

| Omeprazole | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.1) |

Fisher’s exact test was used.

Figure 2.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates in different groups, bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Eradication rates were not significantly different among Group A [without proton pump inhibitors (PPI) pretreatment], B-I (PPI pretreatment for 3-14 d), B-II (15-55 d), and B-III (≥ 56 d) (P = 0.838).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of PPI pretreatment on the rate of H. pylori eradication. There was no significant difference in the eradication rate between patients with and without pretreatment. PPI pretreatment did not affect the eradication rate, even after adjusting for various factors associated with eradication therapy. The present study also showed that the eradication rate was not affected by the duration of PPI pretreatment.

Generally, 80% and 85% cure rates based on intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis, respectively, are regarded as the thresholds for acceptable results of H. pylori eradication[23]. In Korea, the eradication rates with 1 wk standard triple therapy have been reported to be similar[24]. In this regard, it is important to have a thorough knowledge of the factors that affect eradication rate, and we supposed that PPI pretreatment might be one of the possible factors. However, the present study showed that PPI pretreatment did not affect the eradication rate. Generally, patients with gastric neoplasms have lower gastric acid secretory function as compared with those with peptic ulcers, particularly duodenal ulcers. This possibly contributed to the similarity of the eradication rates between the study groups. Our findings were not different from the results of a previous meta-analysis[8].

Meanwhile, previous studies have mostly focused on the effect of the short-term use of PPIs. Therefore, the influence of long-term PPI pretreatment has not yet been elucidated. The effects of long-term PPI use are significant especially in the field of endoscopic resection therapy because the patients who receive this treatment need both the long-term use of PPIs and H. pylori eradication therapy. Although many studies have supported H. pylori eradication because of its prophylactic effect on the development of metachronous gastric cancer, these authors did not consider the effect of PPI pretreatment and the appropriate period for eradication therapy[18-20]. In the present study, we demonstrated that the eradication rates in long-term pretreatment groups were not different from those in the non-pretreatment and short-term pretreatment groups. This finding was observed in a recent study which showed that pretreatment with lansoprazole for 6-8 wk did not influence the eradication rate in peptic ulcer patients[25].

It seems that contrary to the negative effect of PPI treatment before the dual eradication regimen consisting of amoxicillin and PPI[9-11], PPI pretreatment does not affect the eradication rate in the clarithromycin-added triple regimen. Clarithromycin is known to be the most effective single agent against H. pylori[26], and has additive antibacterial activity when used with amoxicillin or PPIs[27]. By adding this powerful antibacterial agent to the regimen, the eradication rate does not seem to be affected by PPI pretreatment.

The main factor affecting the eradication rate of H. pylori might be its clarithromycin resistance as opposed to host factors[28,29]. Clarithromycin-resistant strains are barely eradicated with any dose of clarithromycin or PPI[30]. An in vitro study showed that the MIC values of clarithromycin for resistant strains remained high at various pH levels[31]. This finding implied that increases in intragastric pH by PPIs might not affect the eradication rates of clarithromycin-resistant strains. In Korea, the primary resistance rate of H. pylori to clarithromycin has been reported to be about 20%[32]; a level that is similar to the rates of eradication failure in our study. To rule out the possible confounders of clarithromycin resistance, we suggest that future studies are needed in patients with clarithromycin-sensitive strains.

CYP2C19 genotype status may also be associated with the eradication rate of H. pylori. A previous study reported that the eradication rate in extensive metabolizers was lower than that in poor metabolizers, and extensive metabolizers were successfully retreated with high doses of PPI[33]. We expected that PPI pretreatment might improve the eradication rate in extensive metabolizers because these people show a comparatively slower acid inhibitory effect after PPI use[34]. However, PPI pretreatment did not improve the overall eradication rate. We could explain this result by the fact that the frequency of CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers in East Asians is lower than that of Caucasians[35,36], and therefore the effect in extensive metabolizers might not be fully reflected in the outcomes of our study. For the maximized effect of PPI pretreatment, CYP2C19 genotyping should be considered in future clinical research.

As a retrospective analysis, this study had several limitations. In particular, the enrolled patients received different types of PPI in the pretreatment and H. pylori eradication regimens, and underwent different methods for assessing the eradication. These inconsistencies for various factors were a weak point in our study. We tried to overcome these limitations by the enrollment of a large number of patients and by performing multivariate analysis. Additionally, any potential adverse effects of the PPIs were not investigated in our study. PPIs, however, were not prescribed for more than 6 mo in any patient (the longest, 168 d); and the adverse effects of long-term PPI treatment might be rare. Prospective and controlled studies are needed to confirm the present findings and complement the limitations of the study.

Guidelines recommend that the 13C-urease breath test should be used for confirmation of eradication except in cases where repeat endoscopy is indicated[1,3]. In our study, the rapid urease test and histological examination were performed only in limited cases needing repeated endoscopy (14.4%). Although these tests have > 90% sensitivity and specificity in predicting H. pylori status after antibiotic treatment[37], the 13C-urease breath test should be considered for confirming eradication.

In conclusion, PPI pretreatment did not affect the H. pylori eradication rates, regardless of the length of the medication period. Even after the long-term use of PPI treatment, H. pylori eradication can be attempted without worrying about its effect on eradication therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the financial support of the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation in the program year of 2013.

COMMENTS

Background

After endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms, acid-suppressive treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is used for ≥ 1 mo, to prevent postprocedural complications and to enhance iatrogenic ulcer healing. In these patients, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication decreases the recurrence of gastric neoplasms.

Research frontiers

PPIs in the eradication regimen have been beneficial for the cure of H. pylori infection. Some studies have reported that PPI treatment before the single antibacterial agent, such as amoxicillin, decreases the eradication rate, which can be explained by the fact that PPI pretreatment induces the transition of H. pylori into coccoid dormant forms that are less vulnerable to the actions of antibiotics. It is still controversial whether PPI pretreatment influences the eradication rate.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Most previous studies have assessed the effect of short-term use of PPIs on H. pylori eradication, therefore, the effect of long-term PPI pretreatment is not well known. Their study was conducted to investigate the influence of PPI pretreatment on H. pylori eradication, at different durations of treatment, including long-term pretreatment.

Applications

PPI pretreatment did not affect the H. pylori eradication rates, regardless of medication period. Even after long-term use of PPI treatment, H. pylori eradication can be tried without worrying about its effect on eradication therapy.

Peer review

The study aimed to answer the clinical question as to whether PPI pretreatment influences H. pylori eradication; especially when treatment was > 1 mo. This study had a large cohort size.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Clayton SB, Niu ZS, Shimatan T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lind T, Mégraud F, Unge P, Bayerdörffer E, O’morain C, Spiller R, Veldhuyzen Van Zanten S, Bardhan KD, Hellblom M, Wrangstadh M, et al. The MACH2 study: role of omeprazole in eradication of Helicobacter pylori with 1-week triple therapies. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:248–253. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grayson ML, Eliopoulos GM, Ferraro MJ, Moellering RC. Effect of varying pH on the susceptibility of Campylobacter pylori to antimicrobial agents. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:888–889. doi: 10.1007/BF01963775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erah PO, Goddard AF, Barrett DA, Shaw PN, Spiller RC. The stability of amoxycillin, clarithromycin and metronidazole in gastric juice: relevance to the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:5–12. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan HY, Wang J, Yan GC, Huo XH, Mu LJ, Chu JK, Niu WW, Duan ZY, Ma JC, Wang J, et al. Increasing gastric juice pH level prior to anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy may be beneficial to the healing of duodenal ulcers. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:912–916. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen MJ, Laheij RJ, de Boer WA, Jansen JB. Meta-analysis: the influence of pre-treatment with a proton pump inhibitor on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labenz J, Gyenes E, Rühl GH, Börsch G. Omeprazole plus amoxicillin: efficacy of various treatment regimens to eradicate Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labenz J, Leverkus F, Börsch G. Omeprazole plus amoxicillin for cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Factors influencing the treatment success. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:1070–1075. doi: 10.3109/00365529409094890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayerdörffer E, Miehlke S, Mannes GA, Sommer A, Höchter W, Weingart J, Heldwein W, Klann H, Simon T, Schmitt W. Double-blind trial of omeprazole and amoxicillin to cure Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcers. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1412–1417. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakao M, Malfertheiner P. Growth inhibitory and bactericidal activities of lansoprazole compared with those of omeprazole and pantoprazole against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1998;3:21–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein NS. Chronic inactive gastritis and coccoid Helicobacter pylori in patients treated for gastroesophageal reflux disease or with H pylori eradication therapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:719–726. doi: 10.1309/LJ4D-E2LX-7UMR-YMTH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Yamada T, Ishihara R, Ogiyama H, Yamamoto S, Kato M, Tatsumi K, Masuda E, Tamai C, et al. Effect of a proton pump inhibitor or an H2-receptor antagonist on prevention of bleeding from ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1610–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z, Wu Q, Liu Z, Wu K, Fan D. Proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2-receptor antagonists for the management of iatrogenic gastric ulcer after endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Digestion. 2011;84:315–320. doi: 10.1159/000331138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham NS. Proton pump inhibitors: potential adverse effects. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:615–620. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328358d5b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Yuan YC, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW. Recent safety concerns with proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:93–114. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182333820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, Terao S, Amagai K, Hayashi S, Asaka M. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa S, Asaka M, Kato M, Nakamura K, Kato C. Helicobacter pylori eradication and metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer. Aliment. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24 Suppl 4:214–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Haruma K, Sumii K, Kajiyama G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell NJ, Hunt RH. Time to maximum effect of lansoprazole on gastric pH in normal male volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:897–904. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.103242000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell N, Karol MD, Sachs G, Greski-Rose P, Jennings DE, Hunt RH. Duration of effect of lansoprazole on gastric pH and acid secretion in normal male volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:105–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. A report card to grade Helicobacter pylori therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:275–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim N, Park SH, Seo GS, Lee SW, Kim JW, Lee KJ, Shin WC, Kim TN, Park MI, Park JJ, et al. Lafutidine versus lansoprazole in combination with clarithromycin and amoxicillin for one versus two weeks for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea. Helicobacter. 2008;13:542–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue M, Okada H, Hori S, Kawahara Y, Kawano S, Takenaka R, Toyokawa T, Onishi Y, Shiratori Y, Yamamoto K. Does pretreatment with lansoprazole influence Helicobacter pylori eradication rate and quality of life? Digestion. 2010;81:218–222. doi: 10.1159/000260416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson WL, Graham DY, Marshall B, Blaser MJ, Genta RM, Klein PD, Stratton CW, Drnec J, Prokocimer P, Siepman N. Clarithromycin as monotherapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1860–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cederbrant G, Kahlmeter G, Schalén C, Kamme C. Additive effect of clarithromycin combined with 14-hydroxy clarithromycin, erythromycin, amoxycillin, metronidazole or omeprazole against Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:1025–1029. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broutet N, Tchamgoué S, Pereira E, Lamouliatte H, Salamon R, Mégraud F. Risk factors for failure of Helicobacter pylori therapy--results of an individual data analysis of 2751 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:99–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yakoob J, Jafri W, Abbas Z, Abid S, Naz S, Khan R, Khalid A. Risk factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection treatment failure in a high prevalence area. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:581–590. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami K, Sato R, Okimoto T, Nasu M, Fujioka T, Kodama M, Kagawa J, Sato S, Abe H, Arita T. Eradication rates of clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori using either rabeprazole or lansoprazole plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1933–1938. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lascols C, Bryskier A, Soussy CJ, Tanković J. Effect of pH on the susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to the ketolide telithromycin (HMR 3647) and clarithromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:738–740. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, Nam RH, Chang H, Kim JY, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furuta T, Shirai N, Takashima M, Xiao F, Hanai H, Sugimura H, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T, Kaneko E. Effect of genotypic differences in CYP2C19 on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection by triple therapy with a proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:158–168. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitoh T, Fukushima Y, Otsuka H, Hirakawa J, Mori H, Asano T, Ishikawa T, Katsube T, Ogawa K, Ohkawa S. Effects of rabeprazole, lansoprazole and omeprazole on intragastric pH in CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1811–1817. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sim SC, Risinger C, Dahl ML, Aklillu E, Christensen M, Bertilsson L, Ingelman-Sundberg M. A common novel CYP2C19 gene variant causes ultrarapid drug metabolism relevant for the drug response to proton pump inhibitors and antidepressants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugimoto K, Uno T, Yamazaki H, Tateishi T. Limited frequency of the CYP2C19*17 allele and its minor role in a Japanese population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:437–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollán A, Giancaspero R, Arrese M, Figueroa C, Vollrath V, Schultz M, Duarte I, Vial P. Accuracy of invasive and noninvasive tests to diagnose Helicobacter pylori infection after antibiotic treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1268–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]