Abstract

Objectives:

This research study assessed perceived changes in quality-of-life measures related to participation in complementary services consisting of a variety of nontraditional therapies and/or programs at Pathways: A Health Crisis Resource Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Design:

Survey data were used to assess perceived changes participants ascribed to their experience with complementary services at Pathways. Quantitative data analysis was conducted using participant demographics together with participant ratings of items from the “Self-Assessment of Change” (SAC) measure developed at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Qualitative data analysis was conducted on written responses to an additional survey question: “To what extent has your participation at Pathways influenced your healing process?”

Setting/Location:

Pathways offers a variety of services, including one-to-one sessions using nontraditional healing therapies, support groups, educational classes, and practice groups such as yoga and meditation for those facing serious health challenges. These services are offered free of charge through community financial support using volunteer practitioners.

Participants:

People (126) diagnosed with serious health challenges who used Pathways services from 2007 through 2009.

Interventions:

Participation in self-selected Pathways services.

Measures:

Responses to items on the SAC measure plus written responses to the question, “To what extent has your participation at Pathways influenced your healing process?”

Results:

Quantitative findings: Participants reported experiencing significant changes across all components of the SAC measure. Qualitative findings: Responses to the open-ended survey question identified perspectives on the culture of Pathways and a shift in participants' perceptions of well-being based on their experience of Pathways services.

Conclusions:

Participation in services provided by the Pathways organization improved perceptions of quality of life and well-being and led to more active involvement in the experience of a healing process.

Key Words: Complementary services, self-assessment of change, healing, holistic health, person-centered outcomes

摘要

目标: 本研究对生活质量衡量指标 中与参与补充服务相关的感知变化 进行了评估,而补充服务包括在 Pathways (一家位于明尼苏达州明 尼阿波利斯的健康危机资源中心) 进行的各种非传统治疗和/或序。

设计: 研究人员利用调查数据对发 生感知变化的参与者进行了评估, 并 将 这 些 变 化 归 因 于 他 们 在 Pathways 参加的补充服务。 研究 人员还利用参与者人口统计信息以 及参与者在由位于图森的亚利桑那 大 学 编 制 的 “ 变 化 自 我 评 估 ” (SAC)衡量量表中的项目评级,进 行了定量数据分析。 定性数据分析 则是通过书面回答一个附加调查问 题的方式进行的,而该问题是: “ 您在 Pathways 所参与的服务对您 康复过程的影响程度如何?”

环境/地点: Pathways 可提供多 项服务,其中包括采用非传统康 复 治 疗 的 一 对 一 疗 程 、 支 持 小 组、教育课程以及瑜伽和冥想( 针对面临严重健康挑战的患者) 等实践小组。 该等服务是在社区 财政支持下,通过志愿执业医生 提供的免费服务。

参与者: 在 2007 年至 2009 年期 间,被诊断面临严重健康挑战且采 用 Pathways 服务的人士(126 名。

干预: 参加自我选择的 Pathways 服务。

衡量指标: 对 SAC 衡量量表上各 项的回答,以及对“您在 Pathways 所参与的服务对您康复过程的影响 程度如何?”这一问题的书面回答 结果: 定量分析结果: 参与者报 告称,在 SAC 衡量量表的所有内容 方面均出现显著变化。定性分析结果: 对该开放式调查问题的回答表 明了参与者对 Pathways 文化的看 法,以及他们在参与 Pathways 服 务后于健康认知方面的转变。

结论: 参与 Pathways 机构所提供 的服务提高了参与者对生活质量和 健康的认知,使之更为主动地投入 到康复过程之中。

SINOPSIS

Objetivos:

Este estudio de investigación ha evaluado los cambios percibidos en las mediciones de calidad de vida relacionadas con la participación en servicios complementarios que consisten en una variedad de tratamientos no tradicionales o programas en Pathways: un centro de recursos para crisis sanitarias en Minneapolis (Minnesota).

Diseño:

Se utilizaron datos de encuestas para evaluar los cambios percibidos que los participantes atribuyeron a su experiencia con los servicios complementarios en Pathways. El análisis de datos cuantitativos se llevó a cabo utilizando los datos demográficos de los participantes junto con las puntuaciones otorgadas por los mismos a los elementos de la medición “Autoevaluación del cambio” (Self-Assessment of Change, SAC) desarrollada en la Universidad de Arizona (Tucson). El análisis de datos cualitativos se realizó sobre las respuestas aportadas a la pregunta adicional de la encuesta: “¿En qué medida ha influido su participación en Pathways en su proceso curativo?”

Centro/localización:

Pathways ofrece una variedad de servicios, que incluyen sesiones individuales que utilizan tratamientos curativos no tradicionales, grupos de apoyo, clases educativas y grupos de práctica, como yoga y meditación, para aquellos que se enfrentan a problemas graves de salud. Estos servicios se ofrecen gratuitamente gracias a la ayuda financiera de la comunidad con profesionales voluntarios.

Participantes:

Personas (126) diagnosticadas de problemas graves de salud que utilizaron los servicios de Pathways entre 2007 y 2009.

Intervenciones:

Participación en servicios autoseleccionados de Pathways.

Mediciones:

Las respuestas a los elementos de la medición SAC, además de las respuestas escritas a la pregunta: “¿En qué medida ha influido su participación en Pathways en su proceso curativo?”

Resultados:

Resultados cuantitativos: Los participantes informaron de cambios significativos en todos los componentes de la medición SAC. Resultados cualitativos: Las respuestas a la pregunta abierta de la encuesta identificaron perspectivas sobre la cultura de Pathways y un cambio en las percepciones de los participantes respecto al bienestar basadas en sus experiencias con los servicios de Pathways.

Conclusiones:

La participación en los servicios proporcionados por la organización Pathways mejoró las percepciones de la calidad de la vida y el bienestar y condujo a una implicación más activa en la experiencia del proceso curativo.

INTRODUCTION

Human beings by changing the inner attitudes of their minds can change the outer aspects of their lives.

—William James

Life experiences often change dramatically for those diagnosed with a life-threatening or chronic illness (ie, serious health challenges). Many are no longer able to work and find that their lives now revolve around medical appointments and therapies, leaving little time or energy for living a normal life. Exhausted and bewildered, individuals sometimes stumble upon or actively seek approaches to living beyond traditionally accepted or expected limitations of their illnesses. There is mounting evidence to suggest that nontraditional approaches to dealing with a medical crisis such as emotional support, meditation, use of imagery, a focus on spirituality, and other attitudinal factors can contribute to an individual's healing process.1–3

Complementary care services typically focus on dealing with stress, identifying fears, reframing hope, and regaining control. Such programs often move individuals toward a deeper understanding of life and enable those afflicted to find meaning in their lives when they most need it. Even when physical recovery and cure are unlikely, healing may occur on psychological, emotional, and spiritual levels.1,2,4–7 Severe health challenges can inspire individuals to learn new life skills such as compassion, spirituality, courage, resilience, functionality, and wisdom, thereby enhancing their quality of life.8 The Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS, Petaluma, California) has spent more than a decade focusing on the science of everyday life transformation and has found that following the use of complementary services, there is often a shift in perspective and a feeling of profound change in one's way of being.6,7

Serious illness impacts not only the social and economic lives of millions of Americans (burden of disability, loss of productivity and functioning, reduced quality of life, dissatisfaction with conventional care) but is now contributing to the increasing number of people with chronic illness.9 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Living Well With Chronic Illness: A Call for Public Health Action describes immediate and precise actions that are needed to reduce the burden of chronic illness and argues for conducting outcome-oriented research and program evaluation on interventions used for the “widest possible range of chronic illnesses.”9 Research is needed to address the gap that has appeared between published studies focusing on safety and efficacy of complementary services and shifts in the reported well-being of those who use them.10,11 Such shifts are associated with combinations of approaches to healing, often creating unexpected synergistic effects (ie, conventional therapies combined with a variety of complementary services).9–12

If the use of nontraditional practices is to be evaluated comprehensively, research focus needs to extend to multiple aspects of the healing experience, including how those receiving care (patients) perceive the results. What is often lacking is an understanding of the benefits of these practices and an evaluation of changes from the individual's perspective at the level of the whole person (quality of life, well-being, functionality, and meaningfulness).12–16 To address this issue, Ritenbaugh et al developed the Self Assessment of Change (SAC) measure, a survey instrument designed to identify the extent of perceived personal changes following participation in complementary interventions.17 The intent of this instrument was to enable researchers to collect data on changes that are meaningful to patients.17 The effort by Ritenbaugh et al is in keeping with a core research premise of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), an independent, nonprofit health research organization authorized by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, namely, “keeping the patient's voice central” and being guided by the interests and outcomes of patients and caregivers faced with multiple health challenges.17,18

Pathways is a non-profit, volunteer-sustained organization that provides, free of charge, a variety of one-to-one nontraditional therapy sessions (eg, healing touch, Reiki, reflexology, acupressure, massage) as well as health coaching, support groups, educational classes, and practice groups such as yoga and meditation for those facing serious health challenges (www.pathway-sminneapolis.org). Pathways is not connected to a medical clinic or hospital nor is it part of a particular healthcare system. Its services are considered complementary to conventional treatment. Pathways was created by a group of people who believed that those with serious health problems needed a place to explore a variety of healing modalities and experience the benefits of active participation in a healing process. Presently, more than 150 individuals volunteer at Pathways, 120 as providers of complementary services and 30 as support staff.

Pathways participants are dealing with multiple health issues surrounding a diagnosis such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, or multiple sclerosis—diseases that often include depression, chronic pain, anxiety, and fatigue. Annually, more than 6800 individuals participate in Pathways' services. Those who provide services at Pathways are credentialed and experienced in their particular service; each is carefully evaluated by a committee of the board of directors.

Many individuals learn about Pathways from those who value the services they have experienced; others are referred by their healthcare providers. After participating in an orientation session about the mission and purpose of Pathways, individuals self-select the services they wish to explore.

The research project reported here was designed to provide evidence for the value of complementary services to individuals with a variety of health challenges. The specific data collected assessed perceptions of healing and changes in well-being reported by participants following the use of Pathways services.

METHODS

This research project was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Both quantitative and qualitative analyses were used to identify perceptions of participants who used Pathways services between 2007 and 2009. A survey was initially pilot-tested with 15 individuals and thereafter mailed to 419 participants. An accompanying letter asking for participation with informed consent described the purpose of the survey, the basis for selecting the individuals who received it, and an estimate of how much time the survey would take to complete. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured, and participants were informed that all information would be aggregated before being shared.

One hundred eight (108) completed surveys were returned from the initial mailing. A second mailing was sent to an additional 114 participants, resulting in an additional 18 responses, for a total of 126 surveys. Twenty-two individuals chose to not complete the SAC portion of the survey.

Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative component of the project consisted of demographic data supplied by each participant plus each participant's responses on items from the SAC measure (hereafter, the SAC instrument). In the context of the present study, the SAC instrument was used to retrospectively assess the impact of Pathways' complementary care services. The SAC was developed under a National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM)–funded research project with Cheryl Ritenbaugh, PhD, MP, University of Arizona, Tucson, as the principal investigator and other team members from universities in Florida, Oregon, Michigan, and Canada. This team used extensive interviews and focus groups in the development of the SAC with input from people facing serious health challenges who had participated in a variety of CAM services.17 Ritenbaugh et al developed the SAC instrument with the goal of assessing the patient's perception of effects beyond direct medical treatment goals. These emergent outcomes included unanticipated shifts in perceptions of well-being, energy, clarity of thought, emotional and social functioning, lifestyle patterns, inner life, and spirituality, all outcomes that may or may not have been part of the expectations of those experiencing Pathways' services. A guiding premise of the work of the Ritenbaugh et al group was “that the patient's perception of personal changes associated with a CAM intervention is one of the most relevant measures of impact.”17(p8)

Early in the survey development process, Ritenbaugh et al noticed that people reported “surprise” at changes in their lived experience and shifts in their “internal frame of reference” as a result of their participation in complementary services. This observation motivated the use of a “retrospective pre-test design.”17 This approach has been previously used for the evaluation of learning outcomes in educational and training settings and has been shown to (1) control for response shift bias (reconceptualizing the construct under investigation between the pretest and the post-test) and (2) minimize both overestimation and underestimation of change.19 As reported by Ritenbaugh et al, the evaluative measure termed retrospective pretest has typically been used when the experience of change is perceived to be most salient.19

The SAC development project was presented as a 90-minute symposium at the North American Research Conference on Complementary and Integrative Medicine (NARCCIM) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in May 2009. As a result of this presentation, a larger collaborative group was formed for implementation and further evaluation of the instrument in diverse healthcare settings. Minneapolis Pathways is one of these collaborating projects.

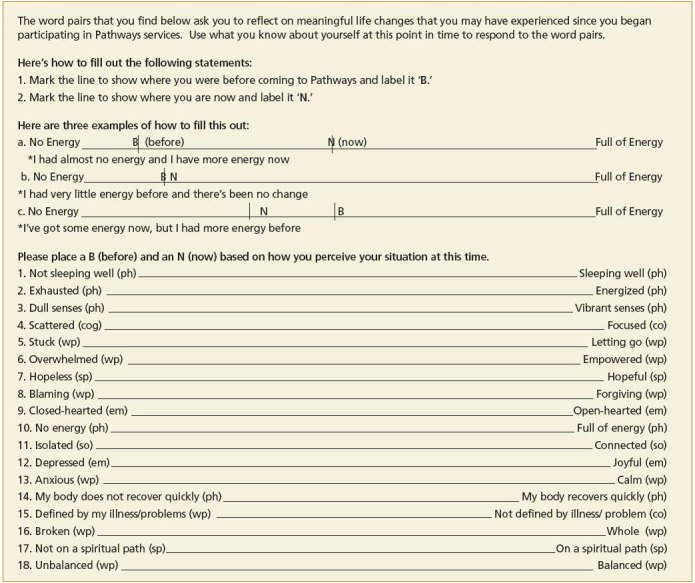

The SAC version used in this research included 18 word pairs that anchor relative positive and negative extremes of key domains of change. Each word pair is presented in a visual scale format on a 100-mm analog scale (Figure 1). According to Ritenbaugh et al, these word pairs encompass five characteristics (domains) of well-being: physical (ph); emotional (em); cognitive (co); social (so): and spiritual (sp), as categorized by the Ritenbaugh team. During the process of categorization, a sixth domain was discovered, which the team termed ‘whole person (wp)' because the items seemed to bridge several domains.”19 Participants in the Pathways research were instructed to mark each line to indicate where they were before (B) they came to Pathways and where they are now (N). For analysis, the 100-mm line connecting each word pair is measured from the left edge to B (before coming to Pathways) and N (now) for data entry purposes. The measures of interest for this research are based on the distance between B and N for each word pair, which reflects participants' shifts in their perceptions of well-being as reflected by that word pair. The completed SAC portion of each participant's survey was mailed to Ritenbaugh and her team who calculated the data measurements and sent them to our statistician. Using Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington) and Stata (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas) software packages, descriptive statistics were developed and paired t-tests were computed for each word pair based on mean scores of participants' ratings.a

Figure 1.

Self-assessment of change measure.

Abbreviations: co, cognitive; em, emotional; ph, physical; so, social; sp, spiritual; wp, whole person.

Use of the SAC instrument contributes data on the perceived effectiveness of complementary services and in this context, provides Pathways with information about the benefits participants report as a result of their experience at Pathways. (See Figure 1 for an illustration of the SAC instrument).

Qualitative Analysis

In order to gain a more complete understanding of the influence of Pathways experiences on participants in their own words, an open-ended question was added to the survey. A qualitative analysis was then undertaken of participant's written responses to the survey question, “To what extent has your participation at Pathways influenced your healing process?” A group consisting of the four authors and the Pathways director conducted this analysis.

The analysis process began with each team member independently sorting responses of each participant into as many categories as seemed appropriate. This process resulted in 23 categories. The team then met to identify themes (major categories) of participant responses.20,21 A master list of themes was constructed based on discussion of each team member's coded data. This process resulted in three major themes (Pathways' healing culture, exploring Pathways' services, and a perceived shift in participants' experience of their condition).22 Fourteen subthemes were identified with one or more subthemes falling under each of the three major themes.

RESULTS

Quantitative Findings

Table 1 presents the demographics of survey respondents. Data from Table 1 indicate that participants in the present study were predominantly women, mainly over 40 years of age, with diverse incomes, employment, and disability. Ninety-four percent had some college or higher educational experience. In response to the question, “What health-related issue brought you to Pathways? (please circle all that apply),” the data indicated that most participants were dealing with multiple health issues. Participants reported using a wide variety of Pathways' services throughout the 2 years represented by the data collected. When asked “During a given month, how often did you use the resources at Pathways?” the majority (54%) indicated two to four times; 19%, five to 10 times; 11%, more than 10 times; and 15% only once a month.

Table 1.

Demographics of Survey Participants (N = 108)

| Age, y | Marital Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 20 | 0% | Single | 34% |

| 20–40 | 11% | Married | 29% |

| 41–60 | 60% | Divorced | 16% |

| 61–75 | 23% | Widowed | 8% |

| Over 75 | 6% | Partnered | 8% |

| Separated | 5% | ||

| Sex | Education | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 85% | High school/GED | 5% |

| Male | 15% | Some college/tech | 28% |

| College graduate | 34% | ||

| Advanced degree | 32% | ||

| Total Household Income, USd | Employment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than $12000 | 20% | Full-time | 16% |

| $12000 to $24999 | 28% | Self-employed | 17% |

| $25000 to $39999 | 16% | Part-time | 12% |

| $40000 to $74999 | 27% | Unemployed | 13% |

| More than $75000 | 9% | Health leave | 2% |

| On disability | 42% | ||

| Serious Illnesses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Arthritis (all types) | 17.5% | ||

| 2. Asthma/respiratory disease | 10.0% | ||

| 3. Cancer | 40.0% | ||

| 4. Chronic pain | 26.2% | ||

| 5. Depression/anxiety disorder | 32.5% | ||

| 6. Diabetes | 4.8% | ||

| 7. Heart/CV disease | 7.9% | ||

| 8. HIV/AIDS | 1.6% | ||

| 9. Other serious health issues | 58.7% | ||

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; GED, General Educational Development degree; tech, technical school.

Of the 126 individuals who returned the survey, 104 completed the SAC component. Twenty-two individuals noted a reason for not completing the SAC measure, the most common being that they felt they had attended too few sessions for this to be meaningful or that they had not attended in the previous year and therefore believed that “now” was not a relevant time point for assessment.

As shown in Table 2, analysis of the SAC measure indicated that the mean ratings of Pathways participants changed from “before” to “now” on every word pair and for every domain of well-being (indicated in parentheses after each word pair). Table 2 also provides the mean ratings for B and N, the difference, C (change between B and N), and the standard deviation of the change in rating organized by magnitude of change for each word pair. The numbers in the table indicate the mean rating on a 0 mm to 100 mm visual analogue scale for each word pair.

Table 2.

Mean Self-assessment Ratings for Each Word Pair Before and Now

| Word Pair | Mean Before | Mean Now | Change (Now-Before) | Standard Deviation of Change | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overwhelmed–Empowered (wp) | 25.8 | 64.1 | 38.3 | 28.1 | P < .001 |

| 2. Stuck–Letting Go (wp) | 29.5 | 66.7 | 37.3 | 29.3 | P < .001 |

| 3. Anxious–Calm (wp) | 32.9 | 66.2 | 33.3 | 27.0 | P < .001 |

| 4. Exhausted–Energized (ph) | 26.3 | 57.3 | 31.0 | 27.8 | P < .001 |

| 5. Unbalanced–Balanced (wp) | 37.9 | 68.3 | 30.4 | 28.9 | P < .001 |

| 6. Depressed–Joyful (em) | 37.1 | 66.9 | 29.8 | 27.3 | P < .001 |

| 7. Hopeless–Hopeful (sp) | 39.1 | 68.9 | 29.8 | 28.4 | P < .001 |

| 8. Scattered–Focused (cog) | 30.7 | 60.5 | 29.8 | 29.4 | P < .001 |

| 9. Broken–Whole (wp) | 40.6 | 70.3 | 29.7 | 30.9 | P < .001 |

| 10. No Energy–Full of Energy (ph) | 32.2 | 60.3 | 28.1 | 29.4 | P < .001 |

| 11. Defined by Illness/Problems (wp)–Not Defined by Illness/Problems (co) | 42.7 | 70.3 | 27.6 | 30.0 | P < .001 |

| 12. Isolated–Connected (so) | 40.5 | 67.7 | 27.2 | 27.8 | P < .001 |

| 13. Dull Senses–Vibrant Senses (ph) | 37.4 | 64.5 | 27.1 | 30.0 | P < .001 |

| 14. Blaming–Forgiving (wp) | 49.9 | 75.3 | 25.4 | 30.4 | P < .001 |

| 15. Closed-hearted–Open-hearted (em) | 52.1 | 76.3 | 24.1 | 29.1 | P < .001 |

| 16. Not On A Spiritual Path–On a Spiritual Path (sp) | 55.3 | 77.2 | 21.9 | 30.0 | P < .001 |

| 17. Not Sleeping Well–Sleeping Well (ph) | 37.3 | 59.1 | 21.8 | 27.8 | P < .001 |

| 18. Body Does Not Recover Quickly–Body Recovers Quickly (ph) | 39.0 | 56.0 | 17.0 | 28.6 | P < .001 |

Abbreviations: co, cognitive; em, emotional; ph, physical; so, social; sp, spiritual; wp, whole person.

The results in Table 2 show positive changes for each of the 18 word pairs in each of the six domains identified by Ritenbaugh et al.17 The change in the mean self-assessment ratings, from before use of the services to date of the survey ranged on the visual analog scale from 38.3–29.7 (top half) to 28.1–17.0 (lower half) with a median of 26.77. (analog scale, 100 mm length). In what follows, we describe in more detail participants' responses to the items in each of the Ritenbaugh et al domains shown in Table 2.17

Whole-person Domain (items 1, 2, 3, 5, 9, and 14 in Table 2).

The Ritenbaugh team has argued that whole person changes are deeply personal, likely only evident to the participant, less visible to others, and hence, less measurable using more traditional survey instruments.17

Five of the seven word pairs in this domain demonstrated relatively high average change ratings of 38.3 to 29.7 with “overwhelmed-empowered” and “stuck-letting go” identified as the most distinct indicators of their self-assessed change. The remaining two items (9 and 14) revealed less perceived change (27.6, 25.4). The before rating for “blaming/forgiving” (14) was higher than any of the other whole person word pairs, indicating that “blaming” by itself does not accurately describe this group's self-assessment. Interestingly, responses indicate a significant change toward “forgiving.”

Physical Domain (items 4, 10, 13, 17, and 18 in Table 2).

Changes in the physical domain are often more tangible to participants, their support persons, and providers.17 Somewhat surprisingly, only one of the items (word pairs) in the physical domain fell into the top half of the change scores shown in Table 2 (“exhausted-energized”), while the remaining items indicated less relative change. Perceptions about “the body recovers quickly” showed the lowest change rating (17) of all the word pairs. Participants' mean ratings indicated that the greatest change in word pairs of the physical domain were “exhausted-energized” (31), “no energy-energy” (29.4), and “dull senses-vibrant senses” (27.1).

Emotional Domain (items 6 and 15 in Table 2).

Changes in the emotional/affective domain reflect a participant's experiential journey from the emotional turmoil that often accompanies serious illness to a new, renewed, or different level of being that develops overtime.17 Two word pairs fell into this domain, one ranked in the top half of Table 2 and the other in the lower half of all word pairs. Participants rated themselves as being more joyful (and less depressed) after Pathways services. While the ratings for “closed-hearted” were relatively high before, participants nevertheless rated themselves as more “open-hearted” after experiencing Pathways' services.

Social and Spiritual Domains (items 7, 12, and 16 in Table 2).

According to Ritenbugh et al, word pairs falling into the social and spiritual domain represent relatedness to self, to others, and to a higher power.17 Three word pairs fell into these domains; only one (“hopeless-hopeful”) was in the top half of change scores. Though participants rated themselves relatively high on “spiritual path” before their Pathways experience, they also reported a significant change in their spiritual experience.

Cognitive Domain (items 8 and 11 on Table 2).

Cognitive abilities reflect skills that are needed to sustain attention, solve problems, and carry out tasks.17 When one is seriously ill, these skills are often compromised, hence improvement is an important aspiration. One cognitive word pair (“scattered-focused”) fell in the top half of change scores. Ritenbaugh's team determined that “defined by illness/problem” (11) belonged in the whole person domain and that “not defined by illness/problem” was in the cognitive domain. On average, participants saw themselves as being more “scattered” than “defined by their illness” before their Pathways experience with similar shifts to a more positive perspective.

Qualitative Findings

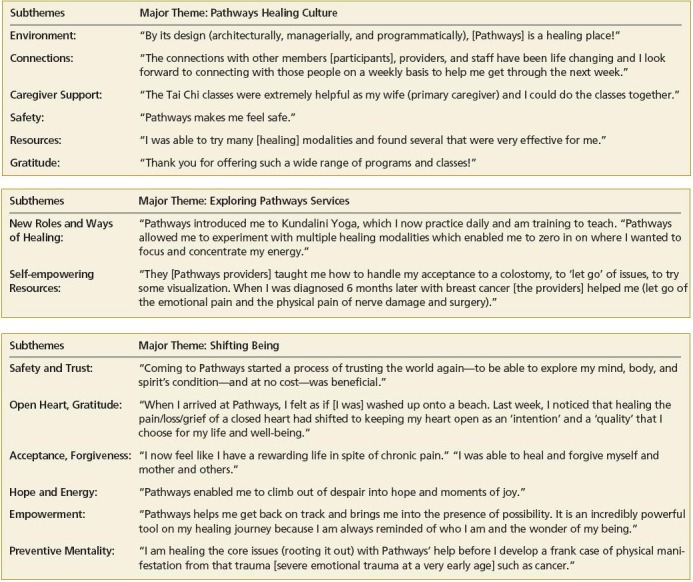

All survey participants (N=126) provided written responses to the survey question, “To what extent has your participation at Pathways influenced your healing process?” As described previously, responses to this question fell into three major themes: (1) what participants experienced when they entered the Pathways healing culture, (2) what participants experienced as they explored Pathways services, and (3) ways participants reported being different after immersion in Pathways culture and services. Figure 2 presents examples of participant statements illustrating the sub-themes within each of the three major themes.

Figure 2.

Results of qualitative analysis of survey question: “To what extent has your participation at Pathways influenced your healing process?” This Figure presents examples of participant statements illustrating the subthemes within each of the three major themes.

Pathways Healing Culture.

Participants reported that their Pathways experience began with its purposefully created healing space and extended to include the connections participants made with others with similar challenging experiences. Participants also commented about the support that Pathways provided for caregivers, the safety that participants and caregivers experienced, and the wealth of available resources.

Exploring Pathways Services.

Having discovered Pathways, participants design a personalized experience that could include establishing new roles and connections, exploring new ways of healing, and using resources that encourage the reclaiming of personal power. Many participants reported taking on new roles, such as becoming volunteers and finding new friendships. Pathways providers and services enabled participants to accept their life circumstances and assisted them in moving forward with their lives. Many participants reported that Pathways services led to significant personal change.

Shifting Being.

Once participants have experienced the healing culture of Pathways, they often reported finding themselves with a new perspective; they become someone they have not known themselves to be. Participants reported feeling safe and open to trust, gratitude, and love. In this state of well-being, participants felt they were better able to cope, accept, and forgive. Finding hope and renewed energy is critical to those facing serious health issues. Participants indicated that they now felt empowered to face challenges they might have previously avoided and reported developing a preventive mentality for dealing with core issues and future health challenges.

DISCUSSION

The SAC instrument used in the present study was designed to assess individual perceptions of personal changes associated with complementary services (rather than relying upon a provider's viewpoint of therapy effectiveness), thereby providing needed data on the gap between published studies showing little efficacy with standard outcome measures and patients' reports of substantial benefits.14 In the present study, quantitative analysis of data from the SAC instrument affirmed that participating in the services provided by Pathways was associated with improved self-assessment on a variety of quality of life measures, with the greatest change being reported in the SAC whole-person domain.

According to Ritenbaugh et al, changes in ratings on word pairs in the whole-person domain did not happen in isolation and are associated with improvement in all word pairs within this domain. This association was found to be true of the top five word pairs that showed a change rating of more than 30. (“overwhelmed/empowered,” “stuck/letting go,” “anxious/ calm,” “unbalanced/balanced”). The physical domain word pair “exhausted/energized” was also in the top 5 change scores. The perception of being “overwhelmed,” “stuck,” and “exhausted” was assessed to be the most salient of the difficulties participants faced before coming to Pathways. These perceptions changed significantly with participation.

The qualitative data of our study indicated that participants felt free to experiment and discover new areas of interest while exploring a variety of Pathways' services. As their time at Pathways continued, participants reported subtle and quiet shifts in their way of being as well as a heightened experience of qualities such as trust, support, and gratitude. Many participants reported taking on new roles such as volunteering or teaching classes and discovering and using self-empowering resources. Participants also reported feeling that they were on a different journey from what they had anticipated when they first arrived at Pathways. On this journey, they learned new coping skills, including the value of forgiveness and having renewed hope and energy. Some reported they began to develop a preventive mentality by healing core issues in their lives.

LIMITATIONS

The results reported here are limited by the nature of the self-report instrument employed, the relatively low survey response rate, and the size and demographics of the Pathways population. Because participants choose to experience different Pathways' services rather than follow a specific therapeutic protocol, no claims can be made that a particular round of therapies produced specific life changes. Personal perceptions are the only confirmation of the therapeutic efficacy of the changes in the quality of life that participants in the present study experienced. While the SAC instrument is an innovative means to assess how such perceptions changed as a result of using Pathways services, 22 participants did not complete the SAC portion of the survey, primarily because the before/now retrospective format did not seem appropriate to their experience.

These limitations suggest that assessments of the results of complementary services such as those provided by the SAC instrument may need to be extended to clearly specified programs over identifiable periods of time. Studies in which participant perceptions are assessed before as well as after the experience of CAM services (rather than in a retrospective format such as was done here) would be an important contribution of future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Though a number of studies have been published on the use, cost savings, and effectiveness of a more integrated approach to healthcare, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to use a survey instrument (the SAC) to capture shifts in perceived well-being that extend beyond the resolution of specific health symptoms.18,22–27 Information about shifts in perceptions can be an important guide to the development of programs and services, adding insights to the more qualitative meanings that participants report as a result of their experience of complementary services. It is such shifts that often foster adherence to beneficial lifestyle changes, which, in turn, can lead to an improved quality of life and enhanced health outcomes.

Despite the limitations of the present study, we have demonstrated an important beginning for what can be learned from an assessment of the perceptions of individuals who use complementary services in the context of health crisis needs. Changes in quality of life measures may be associated with other measures of interest to the healthcare system such as patient satisfaction, compliance with treatment regimens, and participation in healthy lifestyle changes needed for disease management, decreased medication use, and fewer hospitalizations. The SAC instrument offers a means of evaluating changes in overall well-being that may result from complementary services that are not often part of medical treatment. The instrument offers a new way of assessing how individuals perceive change and a measureable indicator of how far they have come in their healing process. Person-centered outcome evaluation can be enriched through the use of the SAC instrument. More such work needs to be done.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted by volunteers at Pathways: A Health Crisis Resource Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and no financial compensation was received. The Self-Assessment of Change (SAC) instrument was developed by Cheryl Ritenbaugh et al at the University of Arizona, Tucson, under a National Institutes of Health-National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH-NCCAM) grant (R01AT003314). Statistical analysis was performed by Eric Barnitt, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Disclosures The authors have completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Footnotes

The version of the SAC used in the present study included 18 word pairs. The final version of the SAC measure, published after this research was underway, was reduced to 16 word pairs based on interviews with individuals who experienced shifts in well-being following CAM and other mind-body therapies (www.selfassessmentofchange.org). (Examples: “No energy/ full of energy” was eliminated because it was used in the example and was felt to be redundant with “exhausted/energized.” “Not on a spiritual path/ on a spiritual path” was eliminated because of expressed confusion and/or discomfort with the terms). Interviews that revealed underlying concepts of faith and spirituality were indexed in word pairs such as hopeless/hopeful, closed-/openhearted, isolated/connected.19

Contributor Information

Mary B. Johnson, St Olaf College, University of Minnesota Center for Spirituality and Healing, Minneapolis (Dr Johnson), United States; Pathways: A Health Crisis Resource Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Dr Johnson), United States.

Sharon W. Bertrand, Pathways: A Health Crisis Resource Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Ms Bertrand), United States; HealthForce Minnesota, Rochester (Ms Bertrand), United States.

Barbara Fermon, Pathways: A Health Crisis Resource Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Ms Fermon), United States; Hearts & Hands Minnesota, Minneapolis (Ms Fermon), United States.

Julie Foley Coleman, Pathways: A Health Crisis Resource Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Ms Coleman), United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dossey L.Consciousness and healing. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon J.Mind body medicine. Total Health. 2005; 26: 54–6 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav V, Shinto L, Morris C, Senders A, Baldauf-Wagner S, Bourdette D.Use of a self-reported benefit of complementary and alternative medicine among multiple sclerosis clients. Int J MS Care. 2006(5): 5–10 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzpatrick AL, Standish LJ, Berger J, Kim JG, Calabrese C, Polissar N.Survival in HIV-1 positive adults practicing psychological or spiritual activities for one year. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007; 13(5): 18–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein BJ, Grasso T.Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park). 2001October; 15(10): 1267–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlitz M, Vieten C, Amorok T.Living deeply. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlitz-Mandala M.The science of transformation in everyday life. Shift. 2005(8): 38–40 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remen RN.The wisdom of the heart: integrating medicine, science, and the spirit Paper presented at: North Memorial Medical Center, Robbinsdale, Minnesota.February4, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine Living well with chronic illness: a call for public health action. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Living-Well-with-Chronic-Illness.aspx AccessedDecember12, 2013

- 10.Cassidy C.Unraveling the ball of string: reality, paradigms and the study of alternative medicine. Advances. 1994; 10(1): 5–31 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fønnebø V, Grimsgaard S, Walach H, et al. Researching complementary and alternative treatments—the gatekeepers are not at home. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007 Feb 11; 7: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy C, Micozzi M, Social and cultural factors. St. Louis, MO: Saunders, Elsevier; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolever R.Collaboration and synergy in the field of health and wellness coaching: naïve or necessary? Global Adv Health Med. 2013; 2(4): 8–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassidy C.Comparing health paradigms. Health Insights Today. 2008; 1(2): 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritenbaugh C, Verhoef M, Fleishman S, Boon H, Leis A.Whole systems research: a discipline for studying complementary and alternative medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003; 9(4): 32–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verhoef M, Lewith G, Ritenbaugh C, Boon H, Fleishman S, Leis A.Complementary and alternative medicine whole systems research: beyond identification of inadequacies of the RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2005; 13(3): 206–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritenbaugh C, Nichter M, Kelly K, et al. Developing a patient-centered outcome measure for complementary and alternative medicine therapies I: defining content and format. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011 Dec 29; 11: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute National priorities for research and research agenda. http://www.pcori.org/assets/PCORI-National-Priorities-and-Research-Agenda-2012-05-21-FINAL1.pdf AccessedDecember12, 2013

- 19.Thompson J, Kelly K, Ritenbaugh C, Hopkins A, Sims C, Coons S.Developing a patient-centered outcome measure for complementary and alternative medicine therapies II: refining content validity through cognitive interviews. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011 Dec 29; 11: 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charon JM.Symbolic interactionism: an introduction, an interpretation, an integration. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speziale HJ, Carpenter DR.Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creswell JW.Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenberg D, Buring J, Hrbek A, et al. A model of integrative care for low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2012: 18(4): 354–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guarneri E, Horrigan BJ, Pechura CM.The efficacy and cost effectiveness of integrative medicine: a review of the medical and corporate literature. Explore (NY). 2010; 6(5): 308–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marx B, Rubin L, Milley R, et al. A prospective patient-centered data collection program at an acupuncture and oriental medicine clinic. J AlternComplement Med. 2013: 19(5): 410–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vorderstrasse A, Ginsberg G, Kraus W, et al. Health coaching and genomics—potential avenues to elicit behavior change in those at risk for chronic disease: protocol for personalized medicine effectiveness study in air force primary care. Global Adv Health Med. 2013: 2(3): 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith L, Lake N, Sillons L, Perlman A, Wroth S, Wolever R.Integrative health coaching: a model for shifting the paradigm toward patient-centricity and meeting new national prevention goals. Global Adv Health Med. 2013; 2(3): 66–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]