Abstract

Anthroposophic medicine is a physician-provided complementary therapy system that was founded by Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman. Anthroposophic therapy includes special medicinal products, artistic therapies, eurythmy movement exercises, and special physical therapies. The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS) was a prospective observational multicenter study of 1631 outpatients starting anthroposophic therapy for anxiety disorders, asthma, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, low back pain, migraine, and other chronic indications under routine conditions in Germany.

AMOS incorporated two features proposed for the evaluation of integrative therapy systems: (1) a sequential approach, starting with the whole therapy system (use, safety, outcomes, perceived benefit), addressing comparative effectiveness and proceeding to the major system components (physician counseling, anthroposophic medicinal products, art therapy, eurythmy therapy, rhythmical massage therapy) and (2) a mix of different research methods to build an information synthesis, including pre-post analyses, prospective comparative analyses, economic analyses, and safety analyses of individual patient data. AMOS fostered two methodological innovations for the analysis of single-arm therapy studies (combined bias suppression, systematic outcome comparison with corresponding cohorts in other studies) and the first depression cost analysis worldwide comparing primary care patients treated for depression vs depressed patients treated for another disorder vs nondepressed patients.

A total of 21 peer-reviewed publications from AMOS have resulted. This article provides an overview of the main research questions, methods, and findings from these publications: anthroposophic treatment was safe and was associated with clinically relevant improvements in symptoms and quality of life without cost increase; improvements were found in all age, diagnosis, and therapy modality groups and were retained at 48-month follow-up; nonrespondent bias, natural recovery, regression to the mean, and adjunctive therapies together could explain a maximum of 37% of the improvement.

Key Words: Anthroposophic medicine, eurythmy therapy, art therapy, rhythmical massage therapy, drug therapy, observational studies, whole system evaluation, review

摘要

人智医学是一个由 Rudolf Steiner 和 Ita Wegman 建立、由医生提供 的补充治疗系统。 人智治疗包括特 殊医药产品、艺术疗法、音语舞运 动锻炼和特殊物理疗法。 人智医学 结果研究 (AMOS) 是一项预期的、 多中心观察研究,参与者为 1631 名德国门诊患者,他们因焦虑症、 哮喘、注意缺陷多动障碍、抑郁 症、腰疼、偏头痛和其他常见疾病 的慢性迹象而开始接受人智治疗。

AMOS 整合了拟定用于评价综合性 治疗系统的两项特征: (1) 采用 顺序的方法,从整个治疗系统开始 (使用、安全性、结果、感知益 处),到比较疗效,再到重要系统 组件(医生咨询、人智医药产品、 艺术疗法、音语舞疗法、节律性按 摩疗法),并 (2) 融合了不同的 研究方法,建立了一个信息综合 体,包括对单个患者数据进行的治 疗前后分析、预期比较分析、经济 分析和安全性分析。 AMOS 促进了 单组治疗研究分析方面的两项方法 学创新(组合式偏差避免,与其他 研究中相应人群进行的系统性结果 比较),并且首次在全世界范围内 进行了抑郁症成本分析,即对接受 抑郁症治疗的基础护理患者、就另 一项疾病接受治疗的抑郁症患者和 非抑郁症患者进行了比较。

AMOS 共发表了 21 个经同行评审 的出版物。 本文概述了这些出版 物的主要研究问题、方法和发现 结果:人智治疗非常安全,可在 不增加费用的情况下在症状和生 活质量方面产生临床相关改善; 这种改善见于所有年龄、诊断和 治疗模式小组的人群之中,并且 保持 48 个月的跟进期;存在无应 答偏差、自然恢复、趋均数回归 和附加治疗这些现象,因而至多 改善 37%。

SINOPSIS

La medicina antroposófica es un sistema terapéutico complementario proporcionado por el médico que fue fundada por Rudolf Steiner e Ita Wegman. La terapia antroposófica incluye productos medicinales especiales, terapias artísticas, ejercicios de movimiento eurítmico y terapias físicas especiales. El estudio de los resultados de la medicina antroposófica (Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study, AMOS) consistió en un estudio prospectivo observacional multicéntrico de 1631 pacientes ambulatorios que comenzaban la terapia antroposófica para trastornos de ansiedad, asma, trastorno de hiperactividad y déficit de atención, depresión, dolor lumbar, migraña y otras indicaciones crónicas bajo condiciones rutinarias en Alemania.

AMOS incorporaba dos características propuestas para la evaluación de sistemas terapéuticos integrales: (1) un enfoque secuencial, comenzando con el sistema terapéutico completo (uso, seguridad, resultados, ventaja percibida), que aborda la eficacia comparativa y continúa con los componentes principales del sistema (asesoramiento del médico, productos medicinales antroposóficos, terapia artística, terapia eurítmica, terapia de masaje rítmico) y (2) una combinación de diferentes métodos de investigación para crear una síntesis de información, que incluye análisis previos y posteriores, análisis comparativos prospectivos, análisis económicos y análisis de la seguridad de los datos del paciente individual. AMOS fomentaba dos innovaciones metodológicas para el análisis de los estudios terapéuticos de un grupo único (supresión del sesgo combinado, comparación sistemática de resultados con las cohortes correspondientes en otros estudios) y el primer análisis a nivel mundial del coste de la depresión comparando pacientes de atención primaria tratados de depresión frente a pacientes deprimidos tratados por otro trastorno frente a pacientes no deprimidos.

Ha resultado en un total de 21 publicaciones revisadas por expertos de AMOS. Este artículo proporciona una visión general de las principales cuestiones de investigación, métodos y los resultados de estas publicaciones: el tratamiento antroposófico era seguro y se asociaba a mejoras clínicamente relevantes en los síntomas y la calidad de vida sin aumento de los costes; se observaron mejoras en todos los grupos de edad, diagnóstico y modalidad de terapia y se mantuvieron en el seguimiento de 48 meses; el sesgo ajeno a los entrevistados, la recuperación natural, la regresión a la media y las terapias adyuvantes juntos podían explicar un máximo del 37 % de la mejoría.

BACKGROUND

Anthroposophic Medicine

Anthroposophic medicine (AM) is a physician-provided whole therapy system, founded in Central Europe the 1920s by Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman.1,2 In AM, the methods and insights of conventional medicine are extended by the methods and insights of anthroposophy. Anthroposophy (Greek: anthropos = man; sophia = wisdom) was established by Rudolf Steiner3 and is founded in three Western traditions: the empirical tradition in the natural sciences from the 17th century onward; the cognitional tradition in philosophy (starting with Plato and Aristotle and culminating in the German idealism of the 19th century); and the esoteric tradition in Christian spirituality. Anthroposophy represents a view of man and nature that is spiritual and that also claims to be profoundly scientific.4

According to anthroposophy, the human organism is formed by not only physical (cellular, molecular) forces but by four classes of formative forces, three of which are also found in nature: (1) in minerals, material forces of physicochemical matter; (2) in plants, formative vegetative forces interact with material forces, bringing about and maintaining the living form; (3) in animals with sensory and motor systems and with a corresponding inner life, a further class of formative forces (anima, soul) interact with material and vegetative forces; (4) in the human organism with its individual mind and capacity of thinking, another class of formative forces (Geist, spirit) interact with the material, vegetative, and soul forces. The interactions of these forces are understood to vary between different regions and organs in the human organism, resulting in a complex equilibrium. This equilibrium can be distorted in various forms of human disease and is sought to be regulated by AM therapies.4,5

AM therapies include special anthroposophic medicinal products (AMPs), nonverbal artistic therapies, eurythmy movement exercises, special physiotherapy modalities such as rhythmical massage therapy, and special nursing techniques.1,4 These therapies are provided by licensed physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, and other qualified nonmedical therapists (AM art and eurythmy therapy).6

AMPs are prepared from plants, minerals, animals, and chemically defined substances. Similar to homeopathic products, AMPs can be prepared in homeopathic potencies,abut many AMPs are prepared in concentrated form.7 AMP therapy differs from homeopathy in other aspects as well:

The rationale for AMP therapy is based on typo-logical correspondences between pathophysiological processes in man and formative forces working in minerals, plants, and animals (see above),4 while the simile principle of homeopathy is based on symptom correspondences8;

the manufacturing of AMPs includes special pharmaceutical processes that are rarely used for homeopathic or other non-AM products: eg, production of metal mirrors by chemical vapor decomposition and processing of herbs by fermentation, toasting, carbonization, incineration, or digestion (heat treatment at 37°C)7; and

potentized AMPs are rarely prepared in potencies higher than D30.9

In AM art therapy, the patients engage in painting, drawing, sculpture modeling, or music or speech exercises, whereby the specific qualities of each artistic medium are utilized to achieve specific effects.10-15

Eurythmy therapy is an artistic exercise therapy involving cognitive, emotional, and volitional elements. In eurythmy therapy sessions, patients exercise specific movements with the hands, the feet, or the whole body. Eurythmy movements are related to the sounds of vowels and consonants, to music intervals, or to soul gestures (eg, sympathy-antipathy). Between therapy sessions, the patients exercise eurythmy movements daily.16,17

Rhythmical massage therapy was developed from Swedish massage. In rhythmical massage treatment, traditional massage techniques (effleurage, petrissage, friction, tapotement, vibration) are supplemented by special techniques such as gentle lifting movements, rhythmically undulating gliding movements, and complex movement patterns like lemniscates.18,19

AM training programs for physicians and therapists are offered at university medical schools or high schools or as separate programs. The programs follow international, standardized curricula and lead to national or international certification as “AM physician,” “AM art therapist,” etc.6 Therapy guidelines exist for AM medical therapy,20 AM art therapy,21 and eurythmy therapy.22

Before prescribing AMPs or referring patients for AM therapies, AM physicians have prolonged consultations with the patients and their caregivers. These consultations are used to take an extended history, to address constitutional and psychosocial aspect of the patients' illness, to explore the patients' and caregivers' preparedness to engage in treatment, and to select optimal, individualized therapy for each patient.1,19 In addition to individualized therapy, a number of standardized AMP treatment regimens involving one or several pre-defined AMPs are available.23

To a certain extent, patients also can start AM therapy independently of a physician, as some AMPs are available without prescription and as patients can go directly to AM therapists.

Currently, AM is practiced in 66 countries worldwide, with the majority of AM physicians working in Europe (Germany, Switzerland, France, Poland, Italy, Spain, The Netherlands) and the Americas (Argentina, United States, Brazil).6 AM is used for the whole spectrum of diseases and is integrated into the whole range of healthcare provision. Thus, in Europe, AM is practiced in 24 inpatient hospitals, 14 of which are hospitals with trauma and emergency services, including two university teaching hospitals and one hospital providing emergency services for a large German airport.6 In the United Kingdom, the National Centre for Social Research has studied AM as a possible model of integrated primary care.19 In Germany, AM is recognized, alongside homeopathy and phytotherapy, as “particular therapy system” under the Medicines Act and is represented by its own committee at the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices.24 Reimbursement of AM treatment costs by health insurance systems differs across countries and is, inverse to the higher concentration of AM practitioners in Europe, more widespread outside Europe than in Europe.6

The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study

The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS) was occasioned by a health benefit program in Germany. The program included reimbursement of AM treatment costs in outpatients in those two areas:

medical therapy: prolonged consultation with AM physicians; and

nonmedical therapy on prescription from AM physicians: AM art therapy, eurythmy therapy, and rhythmical massage therapy.

AMOS was a prospective 4-year observational study of patients starting AM outpatient treatment under routine conditions. Eligibility criteria followed the criteria for inclusion in the health benefit program: adults and children with any chronic condition.25

Patients were enrolled in AMOS between the years 1998 and 2005. When 2-year findings in patients enrolled up to March 2001 were first published,25 there was still a scarcity of published data on use, effectiveness, long-term outcomes, safety, and costs of AM treatment in outpatient care—in general and in patient subgroups according to age, diagnosis, and AM therapy modalities. Much detailed information on these topics became available from AMOS, and the following study analyses were published separately: clinical outcomes in all patients after 4 years,26 in children,27 in the six largest diagnosis groups,28-33 and in the four major therapy modality groups34-37; a nested prospective comparison to conventional treatment for low back pain38; a health costs analysis39; and a safety analysis of AMPs.40 All 16 of these analyses25-40 were pre-planned (eg, a 4-year follow-up had been implemented on all patients enrolled from 1999 to 2005; specific documentation modules had been implemented for children and for 10 diagnoses, six of which had at least 40 patients each enrolled in AMOS and were published separately). In addition, five secondary analyses (outcomes in patients using AMPs,41 outcome predictors in adults,42 impact of depression and depressive symptoms on health costs in adults,43 systematic outcome comparison with corresponding cohorts in other studies,44 combined bias suppression analysis of clinical outcomes45) were published, resulting in a total of 21 peer-review publications25-45 (Table 1). This article provides an overview of the main research questions, methods, and findings from these publications.

Table 1.

Overview of Publications From the Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS)

| Clinical outcomes | Reference no. | |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | Primary analysis | 25 |

| Follow-up analysis after 48 months | 26 | |

| Children | 27 | |

| Diagnosis groups | Anxiety disorders | 28 |

| Asthma | 29 | |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms | 30 | |

| Depression | 31 | |

| Low back pain | ||

| -Comparison to conventional therapy after 12 mo | 38 | |

| -Follow-up analysis after 24 mo | 32 | |

| Migraine | 33 | |

| Therapy groups | Medical treatment | |

| -Prolonged consultations with anthroposophic physicians | 34 | |

| -Anthroposophic medicinal products | 41 | |

| Art therapy | 35 | |

| Eurythmy therapy | 36 | |

| Rhythmical massage therapy | 37 | |

| Supplementary analyses | Outcome predictors in adults | 42 |

| Systematic outcome comparison with corresponding cohorts in other studies | 44 | |

| Combined bias suppression | 45 | |

| Costs | All age groups | 39 |

| Adults: depression vs depressive symptoms vs no depressive symptoms | 43 | |

| Medication safety | 40 |

METHODS

Study Design and Objectives

AMOS was a prospective observational cohort study in a real-world medical setting. The study was initiated by a health insurance company in conjunction with a health benefit program.46 The main objectives were to study clinical outcomes following AM treatment as well as safety and health costs. Further research questions concerned characteristics of AM users, AM therapy administration, use of non-AM adjunctive therapies, and patient satisfaction.

Setting, Participants, and Therapy

All physicians certified by the Physicians' Association for Anthroposophical Medicine in Germany and working in an office-based practice or outpatient clinic were invited to participate in the AMOS study. In the period from July 1, 1998, to December 31, 2005, a total of 151 participating physicians recruited 1631 consecutive patients starting AM therapy under routine clinical conditions. Inclusion criteria for all analyses were the following:

-

1.

Outpatients aged 1 to 75 years and living in Germany; and

-

2.

starting AM therapy for a chronic indication (main disorder)

-

2a)

AM-related consultation of at least 30 minutes followed by new prescription of at least one AMP or

-

2b)

referral to AM therapy by nonmedical therapist: art, eurythmy, or rhythmical massage.

-

2a)

Patients were excluded if they had previously received the AM therapy in question (see inclusion criteria no. 2) for their main diagnosis. Further eligibility criteria applied to individual analyses, eg, a minimum disease duration of 30 days,26-28,41,42 6 weeks,32,38 or 6 months30,31,43 or further age restrictions (Table 2). Inclusion criteria for the analysis of major diagnosis groups were the following:

anxiety disorder28: physician's diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition [ICD-10] F40-F42 or F43.1),

asthma29: physician's diagnosis (ICD-10 J45);

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms30: physician's diagnosis (ICD-10 F90);

depression31: adapted criteria for dysthymic disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV)47;

low back pain32,38: physician's diagnosis (ICD-10 M40-54); and

migraine33: criteria of the International Headache Society.48

Table 2.

Overview of Main Results From the Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study Publications

| Diagnosis | Therapy | N enrolled | Recruitment | Age, y | Primary follow-up assessment | Last follow-up | Reference no. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Evaluable patients | Outcome measurea, improvement from baseline (95% confidence interval), P value | Mo | ||||||

| All | AM | 898 | Jul 1998-Mar2001 | 1-75 | 6 | 92% | Symptom Score: median 2.67 (2.50-2.83), P<.001 | 24 | 25 |

| Disease Score: median 3.50 (3.00-3.50), P<.001 | 25 | ||||||||

| All | AM | 1510 | Jan 1999-Dec 2005 | 1-75 | 48 | 61%b | Symptom Score: mean 2.83 (2.71-2.96), P<.001 | 48 | 26 |

| All | AM | 435 | Jan 1999- Dec 2005 | 1-16 | 6 | 88% | Symptom Score: mean 2.41 (2.16-2.66), P<.001 | 24 | 27 |

| Disease Score: mean 3.00 (2.76-3.24), P<.001 | 27 | ||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | AM | 64 | Jan 1999- Dec 2005 | 17-75 | 6 | 78% | Anxiety Severity, patient rating: mean 3.50 (2.88-4.12), P<.001 | 24 | 28 |

| Anxiety Severity, physician rating: mean 3.60 (2.97-4.22), P<.001 | 28 | ||||||||

| Asthma | AM | 90 | Jan 1999- Dec 2005 | 2-70 | 12 | 74% | Average Asthma Severity: mean 2.61 (1.90-3.32), P<.001 | 24 | 29 |

| ADHD symptoms | AM | 61 | Apr 2001- Dec 2005 | 3-16 | 6 | 77%a | FBB-HKS total score (range 0-3): mean 0.30 (0.18-0.43), P<.001 | 24 | 30 |

| Depression | AM | 97 | Jul 1998-Mar 2001 | 17-70 | 12 | 85% | Center for Epidemiological StudiesDepression Scale (range 0-60)77: median 15.5 (12.5–18.5), P<.001 | 48 | 31 |

| Migraine | AM | 45 | Jan 1999-Dec 2005 | 17-75 | 6 | 76%a | Average Migraine Severity, patient rating: mean 2.84 (2.05-3.64), P<.001 | 24 | 33 |

| Average Migraine Severity, physician rating: mean 3.14 (2.40-3.87), P<.001 | 33 | ||||||||

| Low back pain | AM vs conventional | 38 + 48 | Jul 1998-Sep 2000 | 17-75 | 12 | 89% + 58% | More improvement in AM group for SF-36 Mental Health (P = .045), SF-36 General Health (P = .006), SF-36 Vitality (P = .005). No significant differences for improvements (AM vs conventional) in HFAQ, LBPRS, and other SF-36 scores. | 12 | 38 |

| Low back pain | AM | 75 | Jan 1999-Dec 2005 | 17-75 | 24 | 67% | HFAQ (range 0-100): mean 11.1 (5.5-16.6), P<.001 | 24 | 32 |

| LBPRS (range 0-100): mean 8.7 (4.4-13.0), P<.001 | 32 | ||||||||

| All | Prolonged con- sultation with AM physician | 233 | Jul 1998- Mar 2001 | 1-74 | 12 | 90% | Symptom Score: median 2.97 (2.50-3.25), P<.001 | 48 | 34 |

| Disease Score: median 4.00 (3.50-4.50), P<.001 | 34 | ||||||||

| All | AMPs | 665 | Jan 1999-Dec 2005 | 1-75 | 6 | 85% | Symptom Score: mean 2.43 (2.23-2.63), P<.001 | 12 | 41 |

| Disease Score: mean 3.15 (2.97-3.34), P<.001 | 41 | ||||||||

| All | Art therapy | 161 | Jul 1998-Mar 2001 | 5-71 | 12 | 88% | Symptom Score: median 2.67 (2.25-3.17), P<.001 | 48 | 35 |

| Disease Score: median 4.50 (4.00-5.00), P<.001 | 35 | ||||||||

| All | Eurythmy | 419 | Jul 1998-Mar 2001 | 1-75 | 12 | 88% | Symptom Score: median 2.50 (2.25-2.75), P < .001 | 48 | 36 |

| Disease Score: median 4.00 (3.50-4.00), P < .001 | 36 | ||||||||

| All | Rhythmical massage | 85 | Jul 1998- Mar 2001 | 1-75 | 12 | 85% | Symptom Score: mean 2.63 (2.02-3.23), P < .001 | 48 | 37 |

| Disease Score: mean 3.54 (2.88-4.19), P < .001 | 37 | ||||||||

| All | AM | 1069a | Jan 1999- Dec 2005 | 17-75 | 6 | 85% | Predictors of Symptom Score improvement after 6 and 12 months: baseline symptom severity + SF-36 physical function + SF-36 general health, disease duration | 12 | 42 |

| All | AM | 887 | Jul 1998- Mar 2001 | 1-75 | 6 | 83% | Disease Score without bias suppression: mean 2.97 (2.79-3.14), P < .001; Disease Score after suppression of non- respondent bias, natural recovery, adjunctive therapies, and regression to the mean: mean 1.87 (1.69-2.06), P < .001 | 6 | 45 |

| Asthma, depression, low back pain, migraine, neck pain | AM vs conventional | 392 + 16167 | Jul 1998- Dec 2005 | 17-75 | 3 + 6 +12 | 83% +79% | Improvements in SF-36 scores in AMOS and comparison cohorts of similar magnitude (difference <0.50 SD) in 80.1% (414/517) of comparisons, differences ≥0.50 SD favoring AMOS and comparison cohorts, respectively, in 13.5% and 6.4%, respectively. | 12 | 44 |

| All | AMPs | 662c | Jan 1999-Mar 2001 | 1-75 | 24 | 97%c | Confirmed adverse drug reactions: 2.2% (21/949) of AMPs, 3.0% (20/662) of users, 0.3% (30/11487) of patient-months with AMP use | 24 | 40 |

| All | AM | 717d | Jan 1999-Mar 2001 | 1-75 | 12 + 24 | 88%d | Total health costs: bootstrap mean €3186 (95% confidence interval 3037-3711) in the pre-study year, €3297 (3157-3923) in the first year, €2771 (2647-3256) in the second year. In the second year, costs were reduced by €416 (264-960) from the pre-study year. | 24 | 39 |

| Groups 1-3e | AM | 487 | Jan 1999-Mar 2001 | 17-70 | 12 + 24 | 85%a | Total health costs in the Groups 1-3e averaged €7129, €4371, and €3532 in the pre-study year (P = .008); €6029, €3522, and €3353 in the first year (P = .083); and €4929, €3792, and €4031 in the second year (P = .460). In the second year, costs in Group 1 were reduced by €1808 (1110-4858) from the pre-study year. | 24 | 43 |

Scores of clinical outcome measures are numerical rating scales (0-10) unless otherwise stated.

Analysis after replacement of missing values with last value carried forward, hence all patients with available baseline data (99%) were evaluable for analysis.

The analysis comprised patients with ≥1 of 5 follow-ups available (97%) and using AMPs, n = 662.

The analysis comprised patients with ≥3 of 5 follow-ups available, n = 717/811.

Group 1: patients treated for depression, Groups 2 and 3: patients treated for another disorder, with (Group 2) or without (Group 3) coexisting depressive symptoms.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AM, anthroposophic therapy (art, eurythmy, rhythmical massage, prolonged physician consultations, AMPs); AMPs, anthroposophic medicinal products; FBB-HKS: [German] Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Hyperkinetische Störungen, a questionnaire of core ADHD symptoms; HFAQ, Hanover Functional Ability Questionnaire; LBPRS, Low Back Pain Rating Scale Pain Score; SF-36: Short Form (36) Health Survey; SRM, Standardized response mean effect size (minimal: < 0.20, small: 0.20-0.49, medium: 0.50-0.79, large: ≥0.80).

For the diagnosis group low back pain, additional exclusion criteria were previous back surgery and 11 specific diagnoses.32,38 Other inclusion criteria were for a safety analysis of AMPs, the use of at least one AMP,40 and for three analyses, the availability of follow-up data.38,39,42

AM therapy was administrated at the discretion of the physicians and therapists and evaluated as a whole system49 with subgroup analyses of age, diagnosis, and therapy modality groups. In the latter analyses, patients fulfilling inclusion criteria 2a as well as 2b (see above) were analyzed in group 2b,34-37 except in an analysis of AMP use.41

MAJOR OUTCOME MEASURES

Clinical Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction

For analyses of clinical outcome across indications the primary outcome was disease severity, assessed on numerical rating scales (NRS)50 from 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”): disease score (physicians' global assessment of severity of main diagnosis); symptom score (patients' assessment of severity of one to six most relevant symptoms present at baseline). For diagnosis-specific analyses, all primary outcomes were diagnosis-specific (Table 3). Other major clinical outcomes were quality of life (Table 4) and patient satisfaction.

Table 3.

Disease-specific Clinical Outcome Measures

| Diagnosis group | Outcome measure | Rated by | Score rangea | Properties | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | Anxiety Severity | Patient | 0-10 | One NRS: 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”) | 50 |

| Physician | 0-10 | One NRS: 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”) | 50 | ||

| Asthma | Average Asthma Severity | Patient or caregiver | 0-10 | One NRS: 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”) | 50 |

| ADHD symptoms | FBB-HKS total score | Caregiver | 0-3 | 20 items addressing inattention (9 items), hyperactivity (7 items), and impulsivity (7 items), assessed on Likert scales from 0 (“not present”) to 3 (“very strong intensity”) | 51, 52 |

| Depression | CES-D | Patient | 0-60 | Frequency of 20 symptoms during the last week, assessed on Likert scales from 0 (“rarely or none of the time ≈ less than 1 day”) to 3 (“most or all of the time ≈ 5-7 days”) | 53 |

| Migraine | Average Migraine Severity | Patient | 0-10 | One NRS: 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”) | 50 |

| Physician | 0-10 | One NRS: 0 (“not present”) to 10 (“worst possible”) | 50 | ||

| Low back pain | Hanover Functional Ability Questionnaire | Patient | 0 (minimal function) to 100 (optimal function, no limitation) | Back-specific functional disability measured by 12 activity-related questions (eg, “Can you bend down to pick up a paper from the floor?”), assessed on three-point Likert scales (“Can do without difficulty” / “Can do, but with some difficulty” / “Either unable to do, or only with help”) | 54, 55 |

| Low back pain | Low Back Pain Rating Scale Pain Score | Patient | 0-100 | 6 items addressing back pain (3 items) and leg pain (3 items): current pain, worst pain, and average pain during the last 7 days on numerical rating scales from 0 (“no pain”) to 100 (“unbearable pain”) | 56 |

Higher score values indicate more frequent and/or worse symptoms unless otherwise stated.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; FBB-HKS: [German] Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Hyperkinetische Störungen, a questionnaire of core ADHD symptoms according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10); NRS, numerical rating scale.

Table 4.

Documentation of Quality of Life

| Recruitment period | Age, y | Outcome measure | Scores and scales | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 1998-Dec 2005 | 17-75 | SF-36 Health Survey | Physical and Mental Component Summary scores, eight scales, Health Change item | 57 |

| Jul 1998-Mar 2001 | 8-16 | KINDL 40-Item version | Total score; Psychic, Somatic, Social, and Function subscales | 58 |

| Apr 2001-Dec 2005 | 4-16 | KINDL 24-item version | Total score; Physical Well-Being, Emotional Well-Being, Self-Esteem, Family, Friends, Everyday Functioning | 59 |

| Jul 1998-Mar 2001 | 1-7 | KITA Quality of Life Questionnaire | Psychosoma, Daily Life | 60 |

Abbreviations: KINDL, KINDL Questionnaire for Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents; KITA, [German] Kindertagesstätte, daycare facility for children; SF-36, Short Form (36).

Disease score was documented after 0, 6, and (for patients enrolled up to March 2001) 12 months; all other clinical outcomes after 0, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, and (except quality of life in children) 48 months. The primary follow-up assessment of clinical outcomes was after 6 months25,27,28,30,33,41 or 12 months,29,31,34-38 while follow-up analyses were performed after 12 months,41 24 months,27-30,32,33 or 48 months.26,34-37 Patients' therapy outcome ratings and patient satisfaction with therapy were documented after 6 and 12 months on NRS (0-10).

Safety.

Suspected adverse reactions to medications or therapies were documented by the patients after 6, 12, 18, and 24 months and by the physicians after 6 months (for patients enrolled before April 1, 2001, also after 3, 9, and 12 months). The documentation included suspected cause, intensity (mild/moderate/severe), and therapy withdrawal because of adverse reactions. Serious adverse events were documented by the physicians throughout the study months 0 to 24.

Health Costs.

Outcome of cost analyses25,39,43 was health costs, regardless of diagnosis, in the pre-study year and in the first and (not in25) second study years. All analyses comprised direct health costs for AM therapies and AMPs, physician and dentist visits, psychotherapy, non-AM medication, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and inpatient hospital and rehabilitation treatment as well as indirect costs for sick leave compensation. One analysis43 comprised further direct (non-AM complementary therapies) and indirect (early retirement, mortality) costs.

Data Collection

All data were documented with questionnaires returned in sealed envelopes to the study office. The physicians documented eligibility criteria, disease score, anxiety severity, migraine severity (Table 3), and safety data (see above); the therapists documented AM therapy administration; all other items were documented by the patients or caregivers unless otherwise stated. The patient responses were not made available to the physicians. The physicians were compensated 40 Euro (after March 2001: 60 Euro) per included and fully documented patient, while the patients and their care-givers received no compensation. The data were entered twice by two different persons into Microsoft Access 97 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington). The two datasets were compared and discrepancies resolved by checking with the original data.

Quality Assurance and Adherence to Regulations and Reporting Guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine Charité, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany, and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and largely following the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment. Study reporting followed guidelines for reporting of observational studies.61,62

Data Analyses

All analyses were performed on all patients fulfilling the eligibility criteria for each respective analysis, using SPSS (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois; later PASW Statistics) versions 11-18, StatXact versions 5-9 (Cytel, Inc, Cambridge, Massachusetts), and S-PLUS 8.0 (CANdiensten, Amsterdam).

Sociodemographic Status.

Education levels were classified as low (Grade 1), intermediate (Grade 2), and high (Grade 3) according to the CASMIN educational classification.63

Pre-post Analyses.

Pre-post assessments of clinical outcomes were subject to bivariate analysis using standard parametric and nonparametric methods: For paired continuous data, the t-test or the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used; median differences with 95% confidence intervals were estimated according to Hodges and Lehmann. For bivariate binominal data, the McNemar test was used. All tests were two-tailed. For the diagnosis groups ADHD and asthma,29,30 repeated measures analysis of variance also was performed. Pre-post effect sizes were calculated as standardized response mean and classified as minimal (<0.20), small (0.20-0.49), medium (0.50-0.79), and large (≥ 0.80).64,65

In most cases,25,27-29,31,34-37,41 the main analysis of clinical outcomes was performed on patients with evaluable data for each follow-up without replacement of missing values. Replacement of missing values with the last value carried forward was used in a number of sensitivity analyses27-29,31,34-37,41,45 and as the main analysis in three cases.26,30,33

Nested Prospective Comparative Non-randomized Study.

For the diagnosis group low back pain, a prospective nonrandomized comparative study was nested within the AMOS study.38 In this study, AMOS patients with low back pain were compared to low back pain patients receiving conventional care. The patients in the two groups fulfilled identical eligibility criteria (see “Setting, participants, and therapy” above); AMOS patients were treated by AM physicians, while the patients in the control group were treated by physicians not using AM or other complementary therapies. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction were compared after 6 and 12 months. Clinical outcomes were compared using repeated measures analysis of variance, unadjusted and after adjustment for baseline score of the outcome, for gender, age, low back pain duration, and educational level (university entrance qualification).38 Patient satisfaction was compared using Mann-Whitney U-test.38

Systematic Outcome Comparison With Corresponding Cohorts in Other Studies.

For several other frequent diagnoses in AMOS, this study was the first outpatient study of AM therapy. It was therefore desirable to compare outcomes in AMOS to outcomes of other treatments for these diagnoses. Since only pre-post data were available in AMOS (apart from low back pain, see above), these comparisons would have to be of pre-post changes in patient cohorts derived from different studies. Although such comparisons cannot assess comparative effectiveness, they nevertheless yield information about the relative order of magnitude of treatment outcomes. Such comparisons are often presented in discussion sections as rudimentary narrative reviews; they are often limited to selected studies and often mix different outcomes and follow-up periods.

We devised a systematic extension and upgrading of this type of narrative review, combining the strengths of systematic, criteria-based literature selection and analysis with the descriptive assessment of treatment outcomes. A systematic review was conducted,44 comprising the five largest AMOS diagnosis groups in adult patients: asthma, depression, low back pain, migraine, and neck pain. The five AMOS diagnosis groups were compared to all retrievable patient cohorts with corresponding diagnoses, outcome measures (SF-36 Health Survey66), and follow-up periods (3, 6, or 12 months) receiving other treatment.

Eligibility criteria for the comparison cohorts were

prospective cohort of at least 20 evaluable adult patients (as in the AMOS diagnostic groups);

at least 80% of the patients of the study or a defined subgroup thereof having one of the five diagnoses listed above (the AMOS diagnosis group anxiety disorders was not included in this review because of diagnostic heterogeneity with low sample sizes in relevant diagnostic subgroups: ICD-10 F41.1 generalized anxiety disorder [n = 28], F41.0 panic disorder [n = 25], F40 phobic anxiety disorder [n = 15])28;

patients starting any therapeutic intervention including treatment-as-usual; and

results published in English or one of eight other listed languages.

In addition, for low back pain cohorts, the same exclusion criteria as in the low back pain diagnosis group in AMOS applied (see above). Eligible publications were identified by systematic searches in 10 literature databases.44

For these comparisons, between-group effect sizes were calculated64 and classified as for pre-post analyses. Pre-post changes in an AMOS diagnosis group and in a corresponding cohort were defined to have the same order of magnitude if the between-group effect size was minimal to small (range −0.49 to 0.49 standard deviations). The analyses of this review were descriptive without statistical hypothesis testing.44

Predictors of Clinical Outcome.

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of symptom score change from baseline after 6 and 12 months in adults42 and in children.27

Safety Analyses.

All suspected adverse reactions were classified as reported adverse reactions and subjected to descriptive analysis.25,26,28-33,35-37 Suspected adverse reactions to AMPs as well as serious adverse events were also analyzed individually26,40; the causal relationship of these events medications and nonmedication therapies was classified according to predefined criteria as probable, possible, improbable, no relationship, or unable to evaluate. Events with a possible or probable causal relationship to AMPs were classified as confirmed adverse drug reactions.

Health Costs.

Health costs were calculated by multiplying resource use with unit costs for the respective item. Resource use was documented by the patients, unit costs were calculated from average costs per item in Germany or from reimbursement fees regulated in healthcare benefit catalogues. For health costs, bootstrap means with bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap 95% confidence intervals were calculated, using 2000 replications per analysis.67 All cost analyses25,39,43 compared health costs in the pre-study year to costs in the first and (except in25) second study years. In one analysis, health costs were compared in adult AMOS patients treated for depression and patients treated for another disorder, with or without depressive symptoms, respectively, using generalized linear models.43

Bias and Sensitivity Analyses.

Selection bias.

Since AMOS had a long recruitment period, the study physicians were not able to screen and enroll all eligible patients. A patient selection on part of the physicians could bias results if physicians were able to predict therapy response and if they preferentially screened and enrolled such patients for whom they expected a particularly favorable outcome. It was hypothesized that if such selection bias occurred, the degree of patient selection (equal to the proportion of eligible vs enrolled patients) for each physician would be positively correlated with a favorable clinical outcome in his or her patients. The degree of patient selection was calculated from a survey of AMOS physicians of the number of eligible patients seen in the past 12 months. Correlations between the degree of patient selection and symptom score after 6 months42 and 12 months31 were calculated using Spearman-Rho.

Combined bias suppression.

Since AMOS was a single-arm cohort study (apart from the diagnosis of low back pain), the effect of the therapeutic interventions could not be separated from effects of other factors by comparison to a control group. For this reason a procedure for combined suppression of four relevant bias factors (nonrespondent bias, natural recovery, regression to the mean, and adjunctive therapies) was developed and used for a series of sensitivity analyses of clinical outcomes after 6 or 12 months. Nonrespondent bias was suppressed by replacing missing values with the baseline value carried forward. Regression to the mean was suppressed by replacing disease score at study enrolment with disease score 3 months before study enrolment. Bias from natural recovery was suppressed by restricting the analysis to patients with disease duration of at least 12 months. Bias from adjunctive therapies was suppressed by restricting the sample to patients not using diagnosis-related adjunctive therapies during the first 6 months after study enrolment. The four sensitivity analyses were then combined in an extreme scenario sensitivity analysis that was performed on all patients enrolled up to March 200145 and, with some modifications, in various subgroups.27-37,41

Other sensitivity analyses.

The comparison of SF-36 outcomes in AMOS diagnosis groups and corresponding cohorts was reanalyzed, restricting the number of comparisons to increase comparability of study design, setting, therapy, and baseline score.44 Predictors of clinical outcome were re-analyzed under altered conditions regarding the handling of missing values, the dependent variable, or the follow-up period, and were also re-analyzed in random subsamples.42 Health costs were re-analyzed varying the assumptions about diagnostic criteria,39,43 health resource use,25,43 and costs per resource unit.25,43

RESULTS

An overview of the 21 publications is given in Table 1. The publications can be accessed at http://ifaemm.de/G10_AMOS.htm. Main results are summarized in Table 2.

Patient Recruitment and Follow-up

From July 1, 1998, to December 31, 2005, a total of 1631 patients aged 1 to 75 years were enrolled. Patients enrolled after December 31, 1998 (n = 1544) had follow-up assessments beyond 12 months; this group includes 1510 patients with a disease duration of at least 30 days. The participating physicians (n = 151) and therapists (n = 275) resembled eligible but not participating AM physicians (n = 167) and AM therapists (n = 911) with respect to demographic characteristics, and the included patients resembled screened but not included patients regarding baseline characteristics.26

At the primary follow-up assessments of clinical outcomes after 6 or 12 months, the follow-up rate was 91% and 87%, respectively, in all patients26 (range 77%-92% in subgroups, Table 2). For each primary outcome assessment after 6 months25,27,28,30,33,41 or 12 months,29,31,34-38 nonrespondent analyses were performed: Respondents and nonrespondents at the respective follow-ups did not differ significantly with regard to age, gender, disease duration, disease severity at baseline, and, if appropriate, diagnosis25,27-31,33-38,41 (one exception in 73 nonrespon-dent analyses: significant difference for age in the rhythmical massage therapy group37). Corresponding nonrespondent analyses at the last follow-up after 24 months27,28,31,32,38 or 48 months26,31,34,36 were also mostly negative (five significant differences in 59 analyses). A telephone survey was performed on patients enrolled in the year 2005: the proportion of patients with clinical deterioration at 24-month follow-up was comparable in nonrespondents and respondents.32

Baseline Characteristics

The patients were recruited from 15 of 16 German Federal states.26 Age groups were 1 to 19 years: 29.8% (n = 450/1510); 20 to 39 years: 25.4%; 40 to 59 years: 35.2%; and 60 to 75 years: 9.6%, with a median age of 37.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 12.3-47.1 y, mean 33.8 ± 19.4 y). A total of 81.5% (n = 975/1074) of adults aged 17 to 75 years were women.26

Compared to the German population, adult patients had higher educational and occupational levels and had a healthier lifestyle with regard to smoking, alcohol, and sports activities and were less overweight. The sociodemographic status of adults was similar to the population with regard to income and the proportion of adults living alone and less favorable for work disability pension and sick-leave (Table 5).26

Table 5.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Adult Patients (aged 17-75 y, n = 1074)

| Item | Subgroup | Patients | German Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | % | Reference no. | ||

| Education63 | Low (Grade 1) | 184 | 17.1 | 43 | 68,69 |

| Intermediate (Grade 2) | 530 | 49.3 | 43 | ||

| High (Grade 3) | 360 | 33.5 | 14 | ||

| Wage earners | 39/1074 | 3.6 | 18 | 68 | |

| Unemployed during the past 12 mo | Economically active patients | 37/618 | 6.0 | 10 | 68 |

| Living alone | 208/1069 | 19.5 | 21 | 68 | |

| Net family income <€900 per mo | 160/871 | 18.4 | 16 | 68 | |

| Alcohol use daily (patients) vs almost daily (German population) | Male | 12/198 | 6.1 | 28 | 70 |

| Female | 19/875 | 2.2 | 11 | ||

| Regular smoking | Male | 26/199 | 13.1 | 37 | 71 |

| Female | 92/873 | 10.5 | 28 | ||

| Sports activity ≥1 hour weekly | Age 25-69 y | 484/887 | 54.6 | 39 | 72 |

| Body mass index <18.5 (low weight) | Male | 7/196 | 3.6 | 1 | 68 |

| Female | 61/863 | 7.1 | 4 | ||

| Body mass index ≥25 (overweight) | Male | 64/196 | 32.7 | 56 | 68 |

| Female | 219/863 | 25.4 | 39 | ||

| Permanent work disability pension | 204/1072 | 19.0 | 3 | 73 | |

| Severe disability status | 116/1072 | 10.8 | 12 | 74 | |

| Sick leave days in the last 12 months: mean ± standard deviation | Economically active patients | 32.6 ± 67.3 | 17.0 | 75 | |

Table reproduced from Hamre et al.26

In children,27 the proportion of privately insured patients was comparable to that of the German population.76

Most frequent indications were mental disorders (ICD-10 F00-F99, 35.2%, n = 532/1510); musculoskeletal disorders (M00-M99, 15.4%); respiratory disorders (J00-J99, 9.9%); and neurological disorders (G00-G99, 7.2%).26 The most frequent diagnosis groups are listed in Table 2. Disease duration at baseline was 1 month to 2 months in 4.4% (n = 67/1510) of patients; 3 to 5 months in 5.0%; 6 to 11 months in 8.5%; 1 to 4 years in 38.3%, and ≥5 years in 43.7%, with a median disease duration of 3.5 years (IQR 1.0-8.5 y, mean 6.6 ± 8.2 y).26

Therapy

At enrolment, 19.4% (n = 293/1510) of patients started AM therapy provided by the physician, while the remaining patients were referred to AM art therapy (18.2%), eurythmy therapy (52.6%), or rhythmical massage therapy (9.8%). Of the patients referred to art, eurythmy, or rhythmical massage therapy, 86.8% had the respective therapy, 0.5% did not have the therapy, and for 12.6%, the therapy documentation is incomplete. Median therapy duration was 119 days and median number of therapy sessions was 12 (IQR 84-190 d). AMPs were used by 71.7% (n = 1083/1510) of patients in months 0 to 24.26

Use of diagnosis-related non-AM adjunctive therapies in months 0-6 was analyzed in patients with a main diagnosis of mental, respiratory, or musculoskeletal diseases, headache syndromes, or menstruation-related gynecological disorders: 64.9% (n = 231/356) had no diagnosis-related adjunctive therapy.41

Clinical Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction

Pre-post Analyses.

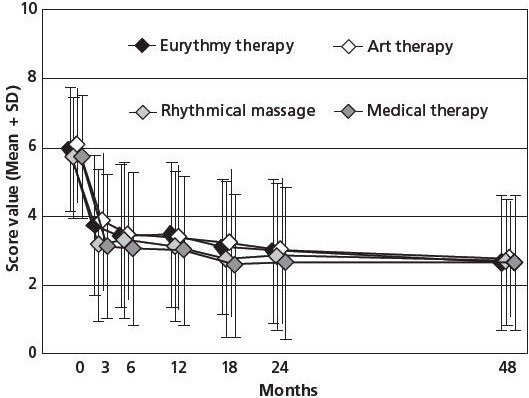

All primary outcome measures improved significantly from baseline to the primary follow-up assessment after 6 months,25-28,30,41 12 months,29,31,34-38 or 48 months;26 in the whole sample,25 in adults and children, in all analyzed diagnosis groups,28-33 and in all therapy modality groups34-37,41 (Figure 1) (P <.001 for all 24 pre-post comparisons). Standardized response mean effect sizes were large for 21 comparisons and medium for three comparisons (Table 6). Improvements were similar in patients not using conventional therapy for their main disorder.41

Figure 1.

Symptom Score stratified by therapy modality group.

Range: 0 (not present) to 10 (worst possible). Patients aged 1-75 years, enrolled 1999-2001, n = 810. Data summarized from references 34–37.

Table 6.

Standardized Response Mean Effect Sizes of Primary Outcome Measures

| Groups | Patient-reported Outcome Measuresa | Month | SRM | N | Reference no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Primary analysis | Symptom score | 6 | 1.09 | 736 | 25 |

| Follow-up analysis | Symptom score | 48 | 1.13 | 1510 | 26 | |

| Children | Symptom score | 6 | 0.97 | 381 | 27 | |

| Diagnosis groups | Anxiety disorders | Anxiety severity | 6 | 1.71 | 44 | 28 |

| Asthma | Average asthma severity | 12 | 0.90 | 66 | 29 | |

| ADHD symptoms | FBB-HKS total score [parent rating] | 6 | 0.68 | 60 | 30 | |

| Depression | CES-D | 12 | 1.20 | 75 | 31 | |

| Migraine | Average migraine severity | 6 | 1.09 | 44 | 33 | |

| Low back pain | HFAQ | 24 | 0.59 | 46 | 32 | |

| Low back pain | LBPRS | 24 | 0.59 | 47 | 32 | |

| Therapy groups | Medical treatment | |||||

| -Prolonged consultation with AM physician | Symptom score | 12 | 1.05 | 184 | 34 | |

| -AM products | Symptom score | 6 | 1.01 | 559 | 41 | |

| Art therapy | Symptom score | 12 | 1.03 | 135 | 35 | |

| Eurythmy therapy | Symptom score | 12 | 1.04 | 336 | 36 | |

| Rhythmical massage therapy | Symptom score | 12 | 1.14 | 59 | 37 |

| Physician-reported outcome measuresa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Disease score | 6 | 1.23 | 738 | 25 | |

| Children | Disease score | 6 | 1.30 | 362 | 27 | |

| Diagnosis groups | Anxiety disorders | Anxiety severity | 6 | 1.52 | 57 | 28 |

| Migraine | Average migraine severity | 6 | 1.30 | 44 | 33 | |

| Therapy groups | Medical treatment | |||||

| -Prolonged consultation with AM physician | Disease score | 12 | 1.52 | 155 | 34 | |

| -AM products | Disease score | 6 | 1.35 | 583 | 41 | |

| Art therapy | Disease score | 12 | 1.76 | 97 | 35 | |

| Eurythmy therapy | Disease score | 12 | 1.34 | 237 | 36 | |

| Rhythmical massage therapy | Disease score | 12 | 1.45 | 56 | 37 | |

Outcome measures are described in Table 3.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AM, anthroposophic medicine; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; FBB-HKS: [German] Fremdbeurteilungsbogen für Hyperkinetische Störungen, a questionnaire of core ADHD symptoms; HFAQ, Hanover Functional Ability Questionnaire; LBPRS, Low Back Pain Rating Scale Pain score; SRM, standardized response mean effect size (minimal: <0.20, small: 0.20-0.49, medium: 0.50-0.79, large: ≥0.80).

Quality-of-life scores (SF-36, KINDL, KITA, see Table 4) improved significantly from baseline to the primary follow-up assessments in the whole sample25 and in most diagnosis28,31,32,38 and therapy modality34-37,41 groups (122 significant improvements in 138 pre-post analyses). Of the 16 pre-post analyses not showing significant improvements, five analyses had a sample size of < 17 patients. All significant symptom and quality of life improvements were maintained at the last follow-up assessment after 12 months,41 24 months,27-30,32,33 and 48 months,26,34-37 respectively (one exception: KINDL total score in the asthma group, n = 1229).

At 6-month follow-up, the patients' mean rating of therapy outcome (0 = no help at all, 10 = helped very well) was 7.23 ± 2.39 points; patient satisfaction with therapy (0 = very dissatisfied, 10 = very satisfied) was 7.94 ± 2.20 points.26 In age, diagnosis, and therapy modality subgroups, the mean therapy outcome ratings ranged from 6.29 (ADHD symptoms30) to 7.54 (depression31) and therapy satisfaction ranged from 7.45 (ADHD symptoms30) to 8.23 (AM art therapy)35 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Patients' Rating of Therapy Outcome, Patient Satisfaction With Therapy

| Groups | Therapy Outcome Rating | Satisfaction With therapy | Reference no. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Sd | Na | Mean | Sd | Na | |||

| All patients | 7.23 | 2.39 | 1275 | 7.94 | 2.20 | 1273 | 26 | |

| Age groups | Adults | 7.33 | 2.33 | 556 | 8.01 | 2.16 | 558 | 77 |

| Children | 7.12 | 2.56 | 370 | 7.87 | 2.27 | 371 | 27 | |

| Indications | Anxiety disorders | 6.82 | 2.74 | 50 | 7.61 | 2.65 | 49 | 29 |

| Asthma | 7.54 | 2.44 | 65 | 8.19 | 2.12 | 64 | 30 | |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity symptoms | 6.29 | 2.70 | 52 | 7.45 | 2.12 | 51 | 31 | |

| Depression | 7.54 | 1.76 | 74 | 7.92 | 1.86 | 74 | 31 | |

| Low back painb | ||||||||

| -Anthroposophic therapy (AMOS) | 7.28 | 2.31 | 29 | 7.62 | 2.30 | 29 | 38 | |

| -Conventional therapy (control group) | 5.58 | 2.55 | 26 | 6.50 | 2.39 | 26 | 38 | |

| Migraine | 7.33 | 2.42 | 33 | 7.72 | 2.05 | 32 | 33 | |

| Therapy modalities | Medical treatment | |||||||

| -Prolonged consultations with anthroposophic physicians | 7.21 | 2.64 | 182 | 7.81 | 2.45 | 182 | 34 | |

| -Anthroposophic medicinal products | 7.12 | 2.46 | 550 | 7.80 | 2.26 | 546 | 41 | |

| Art therapy | 7.52 | 1.95 | 132 | 8.23 | 1.79 | 133 | 35 | |

| Eurythmy therapy | 7.42 | 2.29 | 349 | 8.08 | 2.19 | 352 | 36 | |

| Rhythmical massage therapy | 7.50 | 2.34 | 62 | 8.18 | 2.08 | 62 | 37 | |

Patients' ratings of therapy outcome (0 = no help at all, 10 = helped very much) and patient satisfaction with therapy (0 = very dissatisfied, 10 = very satisfied) at 6-month follow-up, analyzed in all patients and in different age, diagnosis, and therapy modality groups.

Patients who returned the 6-month follow-up questionnaire with evaluable responses to the respective item.

A nested prospective comparative nonrandomized study of patients with low back pain.38

Nested Prospective Comparative Nonrandomized Study.

In a nested prospective nonrandomized comparative study, the AMOS diagnosis group low back pain was compared to patients starting conventional treatment for low back pain after 6 and 12 months:38 In both groups analyzed together, back pain (Low Back Pain Rating Scale Pain Score56), back function (Hanover Functional Ability Questionnaire54), symptom score, and some SF-36 scales improved. Three SF-36 scales were significantly more improved in AMOS patients (Mental Health, General Health, and Vitality); other improvements did not differ significantly between the two groups. At 6-month follow-up, AMOS patients had significantly higher therapy outcome ratings (P = .009) and showed a trend for higher patient satisfaction (P = .051) than patients receiving conventional care (Table 7).38

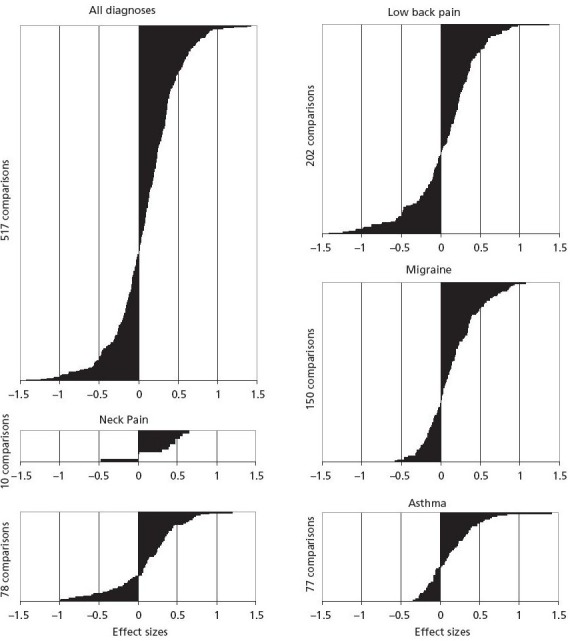

Systematic Outcome Comparison With Corresponding Cohorts in Other Studies.

In a systematic review, adult AMOS patients with asthma, depression, low back pain, migraine, and neck pain (n = 392 patients) were compared to other patient cohorts with corresponding diagnoses receiving other treatment.44 A total of 63 publications fulfilled all eligibility criteria for the review (see Methods section). These publications reported one or more comparison cohorts with low back pain (n = 24 publications), depression (n = 13), migraine (n = 13), asthma (n = 11), and neck pain (n = 2), comprising 84 comparison cohorts with 16 167 patients. A total of 517 comparisons of 10 different SF-36 scales showed improvements largely of the same order of magnitude in AMOS subgroups and corresponding cohorts (minimal-to-small differences in 80% of the comparisons), with medium-to-large differences favoring AMOS and the corresponding cohorts in 14% and 7% of the comparisons, respectively (Figure 2). Sensitivity analyses had only small effects on the results.44

Figure 2.

Outcome comparisons stratified by diagnoses.

Differences between pre-post improvements of Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS) cohorts and improvements of corresponding cohorts for all SF-36 scales and summary measures, expressed in effect sizes and ordered in increasing magnitude: for all diagnoses and for individual diagnoses (n = 517 comparisons in total). Positive effect sizes indicate larger pre-post improvement in AMOS cohort than in corresponding cohort.

Figure reproduced from Hamre et al.44

Predictors of Clinical Outcomes.

In adults42 and children,27 improvements of symptom scores after 6 and 12 months were positively predicted by higher baseline symptom intensity and negatively predicted by longer disease duration. Baseline symptom severity was the strongest predictor, accounting for 25% and 17% of the variance after 6 months in adults and children, respectively (total models 32% and 23%, respectively). In adults, improvements were also positively predicted by better physical function, better general health, and (in most sensitivity analyses) higher education level and higher therapy goal at baseline.42 The latter variable was not analyzed in children. In children, improvements were also negatively predicted by baseline disease score.27

Bias Analyses.

Patient selection.

It was estimated that the physicians enrolled 31% of all eligible patients.42 The degree of patient selection for each physician did not correlate with symptom score improvements after 6 or 12 months.31,42

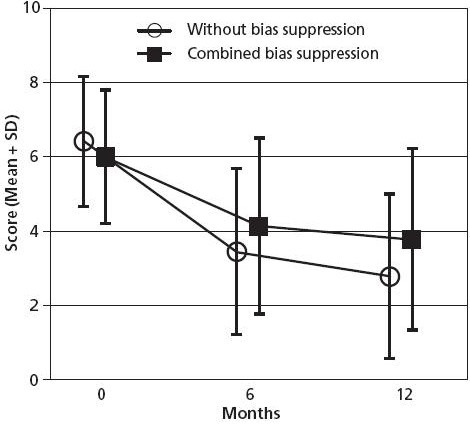

Combined bias suppression.

In an analysis of all patients enrolled up to March 2001, four bias factors (nonrespondent bias, natural recovery, regression to the mean, and adjunctive therapies) could together explain a maximum of 37% of the 0- to 6-month improvement of disease score, with a residual improvement of 1.87 points (95% CI 1.69-2.06 points) (Figure 3).45 Corresponding analyses of primary outcome measures were performed in children27 and in the different diagnosis25,27-33 and therapy modality groups;34-37,41 suppressing one,32 two,29,30,36 three,27,28,34,35 or four31,37,41 bias factors. These analyses yielded similar results to the main bias analysis45 (a maximum of 35% of the improvement explained in depression group31) or a lower percentage explained (range 0%-19% in other analyses).

Figure 3.

Disease score without and with combined bias suppression.

Patients aged 1-75 years, enrolled 1999–2001 with disease score available at baseline, n = 887. Figure reproduced from Hamre et al.45

Safety

The incidence of confirmed adverse reactions to AMPs was 3.0% (n = 20/662) of users; 2.2% (n = 21/949) of the AMPs used; and 0.3% (n = 30/11 487) of patient-months of AMP use. Confirmed adverse reactions of severe intensity occurred in 0.3% of AMP users while 1.5% had a confirmed reaction leading them to stop their AMP use.40

The incidence of reported adverse reactions to art, eurythmy, or rhythmical massage therapy was 2.0% (n = 21/1065) of therapy users for any reaction; 0.4% (n = 4) for reactions of severe intensity; and 0.3% (n = 3) for reactions leading patients to stop their therapy.26

No serious adverse reactions to any AMPs or AM therapies occurred.26

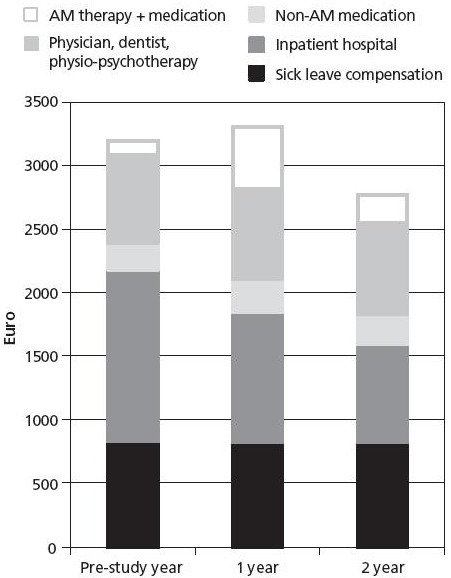

Health Costs

In a preliminary analysis without statistical hypothesis testing, total health costs were reduced by 4% from the pre-study year to the first study year.25

In a subsequent analysis of a larger sample size (Figure 4), costs in the first study year did not differ significantly from costs in the pre-study year, whereas in the second year, costs were significantly reduced by 13%.39 Both these analyses25,39 consisted of adults and children.

Figure 4.

Health costs.

Patients aged 1–75 years, enrolled 1999–2001 with available data for ≥3 of 5 follow-ups, n = 717. Figure reproduced from Hamre et al.39

Abbreviation: AM, anthroposophic medicine.

In an analysis of adult patients treated for depression, costs in the pre-study year were 102% and 63% higher than costs for patients treated for another disorder with and without depressive symptoms, respectively. Among the patients with depression, compared to the pre-study year, costs in the second study year were significantly decreased by 27%, while costs in the other two groups (patients with other disorders with or without depressive symptoms) showed little change.43

The cost reduction observed in these analyses was largely due to a reduction of inpatient hospitalization that could not be explained by secular trends during the study period.39 Another possible explanation is frequent or long hospitalization early in the course of disease (diagnostic assessment, therapy initiation) followed by a normalization of hospitalization rates. A sensitivity analysis suggested that this factor could at maximum explain 37% of the hospitalization reduction.39 Other sensitivity analyses25,39,43 had only small effects on the results.

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

We have summarized methods and findings in all 21 peer-review publications from the AMOS study,25-45 a 4-year prospective observational study of multimodal AM therapy for chronic disease in routine outpatient care. AMOS involved more than 400 therapy providers and more than 1600 patients with mental, musculoskeletal, respiratory, or neurological disorders or other chronic conditions. Following AM therapy (physician counseling, AMPs, art therapy, eurythmy therapy, rhythmical massage therapy), substantial and sustained improvements of disease symptoms and quality of life were observed.26 These improvements were found in adults25,42 and children27 and in all analyzed diagnosis25,27-33 and therapy modality groups.34-37,41 Quality of life improvements in adults were at least similar to improvements in patients receiving conventional care.38,44 Health costs were not increased, although the patients were starting new AM therapy; in the second year, the costs were significantly decreased.39 Adverse reactions to AM treatment were infrequent and mostly of mild-to-moderate intensity.34-37,40 Patient satisfaction was high.26

Significance of the Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study

In terms of the numbers of participating therapy providers and patients, the scope of documentation, and the length of follow-up, AMOS is by far the largest clinical outcome study of AM to date. Nonetheless, one might ask why such a large number of publications has been forthcoming from this project. The main reason is the scarcity of data on clinical outcomes, costs, and safety of AM treatment for chronic noncancer conditions. AMOS includes the first clinical studies of anxiety disorders,28 nonmedication AM therapy for migraine,33 and rhythmical massage therapy for any indication,37 as well as the first large studies of ADHD30 and of eurythmy therapy.36 In the field of primary care research, AMOS includes the first studies of depression,31 low back pain,32,38 AM medical treatment for chronic disease,34 and AM art therapy for any indication,35 as well as the first large study of AM treatment for children with chronic disease.27 AMOS has yielded the first multivariate predictor analyses of long-term outcome following AM treatment for chronic noncancer indications in adults27 and children,27 the first detailed safety analysis of AMPs within a large prospective cohort study,40 and the first detailed economic analysis of AM treatment.39 These comparisons refer to published and unpublished studies on AM.78 A comparison restricted to peer-review publications would underline the pioneer position of AMOS even more.

Apart from its significance for the evaluation of AM treatment, AMOS has also fostered two methodological innovations for the analysis of single-arm therapy studies (combined bias suppression45 and systematic outcome comparison with corresponding cohorts in other studies44) and the first depression cost analysis worldwide comparing primary care patients treated for depression vs depressed patients treated for another disorder vs non-depressed patients.43

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of AMOS and the body of AMOS publications include a naturalistic real-world therapy setting; a large sample size; a long follow-up period; the combination of generic and disease-specific outcome measures; a high representativeness of the participating physicians, therapists, and patients; detailed cost and safety analyses; and the widespread use of sensitivity analyses.

The AMOS study had an observational single-arm design. In addition, a concurrent nonrandomized control group was available for the diagnosis group low back pain,38 but the validity of this comparison is limited by a high nonrespondent rate of 42% in the control group. Furthermore, a systematic comparative review was conducted in order to assess the order magnitude of the improvements in AMOS relative to improvements in other therapy studies. Comparative samples were identified through systematic reviews for five common AMOS diagnoses. Outcomes were then evaluated to assess similarities and differences between AM treatment outcomes and those for a variety of other treatment strategies. These nonconcurrent comparisons were descriptive and limited to comparative order of magnitude.44

To further compensate for the limitations of the pre-post design, a systematic procedure to assess the potential impact of four possible causes of pre-post improvements, apart from AM therapy (nonrespon-dent bias, natural recovery, regression to the mean, adjunctive therapies) on clinical outcomes was developed and used in AMOS. This combined bias suppression procedure is novel and needs to be further evaluated in future studies.45

Another issue is the possibility of selection bias from physicians' expectations of the patients' future therapy response (see Methods for details). Extensive analyses suggest that if such a patient selection did occur, this selection did not affect clinical outcomes.31,42

The integration of different diagnosis-specific documentation modules into one research project in routine outpatient care necessitated some compromises: eg, there were no data on airway caliber in asthma patients29 and no structured psychiatric interviews for diagnostic assessment of patients with mental disorders.28,30,31

Comparison to Other Studies of Multimodal Anthroposophic Treatment

Multimodal AM treatment (including AMPs and nonmedication AM therapies) for chronic noncancer indications has been investigated in other studies with various indications: anorexia nervosa,79-81 asthma,82 epilepsy,83 hepatitis C,84,85 inflammatory rheumatic disorders,85 intervertebral disc disease,86 and rehabilitation after stroke.87 These studies were performed in inpatient hospitals79-81,84,87,88or specialized outpatient clinics82,83,85,86 and had, like AMOS, an observational design. All studies showed benefit from AM treatment.78 The AMOS study, in predominantly primary care settings, showed substantial and sustained improvements in symptoms and quality of life25 in accordance with these studies from specialized settings.

Implications for Practice

Within the limits of an observational, largely pre-post design, the AMOS study suggests that AM therapies can be useful in the long-term care of patients with chronic noncancer disease.

Implications for Research

The analysis and publication strategy for AMOS incorporates two features proposed for the evaluation of complementary or integrative therapy systems. The first feature is a sequential approach,89,90 starting with the whole therapy system (use, safety, outcomes, perceived benefit),25-27,42,45 addressing comparative effectiveness,38,44 and then proceeding to an evaluation of the major system components.34-37,41 The second feature is using a mix of different research methods to build an information synthesis,90 including pre-post observational studies,25-37,41,45 comparative observational studies,38,43 systematic reviews,44 economic analyses,39,43 and safety analyses of individual patient data.40 Notably, an evaluation strategy incorporating such features89,90 will usually comprise a series of research projects, while AMOS was one single project.

Future studies on AM treatment for chronic disease will probably not attempt to replicate AMOS by including all age groups and all chronic indications but rather focus on selected diagnoses in adults or children. However, AMOS has shown that further investigations on AM therapy for the most frequent diagnosis groups in this project may be worthwhile.

There is scope for experimental and observational studies, further whole-system evaluations, and evaluations of individual therapy components, also including physiological effects of AM treatment.91-94 In addition, there is scope for qualitative studies exploring the experiences of patients undergoing AM treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

In the AMOS study, multimodal AM treatment for outpatients with chronic disease was safe and was associated with clinically relevant and sustained improvements in symptoms and in quality of life, as well as reduced costs.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks go to the study physicians, therapists, and patients for participating.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest and had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Footnotes

Funding The AMOS and subsequent publications were funded by the Innungskrankenkasse Hamburg (now IKK Classic) and the Software-AG Stiftung with supplementary grants from the Deutsche BKK, The Betriebskrankenkasse des Bundesverkehrsministeriums, the Christophorus-Stiftungsfonds in der GLS Treuhand e. V., the Förderstiftung Anthroposophische Medizin, the Dr Hauschka Stiftung, the Helixor Stiftung, the Mahle Stiftung, Wala-Heilmittel GmbH, and Weleda AG. The sponsors had no influence on design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

All homeopathic products and many AMPs are “potentized,” ie, successively diluted, each dilution step involving a rhythmic succussion (repeated shaking of liquids) or trituration (grinding of solids into lactose monohydrate). A D30 potency (also called 30X) has been potentized in a 1:10 dilution for 30 times, resulting in a 1:10−30 dilution.

Contributor Information

Harald Johan Hamre, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten-Herdecke, Freiburg, Germany (Dr Hamre).

Helmut Kiene, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten-Herdecke, Freiburg, Germany (Dr Kienle).

Renatus Ziegler, Institute Hiscia, Society for Cancer Research, Arlesheim, Switzerland (Dr Ziegler).

Wilfried Tröger, Clinical Research Dr Tröger, Freiburg, Germany (Dr Tröger).

Christoph Meinecke, Community Hospital Havelhöhe, Berlin, Germany (Dr Meinecke).

Christof Schnürer, Albert-Fraenkel-Centrum, Badenweiler, Germany (Dr Schnürer).

Hendrik Vögler, Ita Wegman Therapeutikum, Dortmund, Germany (Dr Vögler). Dr Vögler was the contact person for the Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS) in the Physicians' Association for Anthroposophical Medicine in Germany..

Anja Glockmann, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten-Herdecke, Freiburg, Germany (Ms Glockmann).

Gunver Sophia Kienle, Institute for Applied Epistemology and Medical Methodology at the University of Witten-Herdecke, Freiburg, Germany (Dr Kiene).

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans M, Rodger I. Healing for body, soul and spirit: an introduction to anthroposophical medicine Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris Books; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner R, Wegman I. Fundamentals of therapy [First edition 1925]. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Legacy Reprints; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindenberg C. Rudolf Steiner—a biography Great Barrington, MA: Steiner Books; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kienle GS, Albonico HU, Baars E, Hamre HJ, Zimmermann P, Kiene H. Anthroposophic medicine—an integrative medicine system originating in Europe. Global Adv Health Med. 2013; 2(6): 20–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heusser P. Anthroposophische Medizin und Wissenschaft. Beiträge zu einer integrativen medizinischen Anthropologie. [Anthroposophic medicine and science. Towards an integrative medical anthropology]. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer-Verlag; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann P, Winkler M, Arendt A, et al. Facts and figures on anthroposophic medicine worldwide Brussels, International Federation of Anthroposophic Medical Associations. Last update: 2012. http://www.ivaa.info/fileadmin/editor/file/Facts_and_Figures_AM_WorldwideJuly2012_Final_Public_Light.pdf AccessedNovember13, 2013

- 7.Anthroposophic Pharmaceutical Codex APC, 3rd ed.Dornach, Switzerland: The International Association of Anthroposophic Pharmacists IAAP; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bornhöft G, Matthiessen PF. Homeopathy in healthcare: effectiveness, appropriateness, safety, costs Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basic information on the working principles of anthroposophic pharmacy. 2nd ed.Dornach, Switzerland: The International Association of Anthroposophic Pharmacists IAAP; 2005.http://www.iaap.org.uk/downloads/principles.pdf AccessedNovember13, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauschka-Stavenhagen M. Fundamentals of artistic therapy, based on spiritual science. Spring Valley, NY: Mercury Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collot d', Herbois L. Light, darkness and color in painting therapy. Dornach: Goetheanum Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denjean-von Stryk B, von Bonin D, Krampe M. Anthroposophical therapeutic speech. Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris Books; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felber R, Reinhold S, Stückert A. Musiktherapie und Gesang [Music therapy and singing]. Stuttgart, Germany: Verlag Freies Geistesleben &; Urachhaus; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golombek E. Plastisch-Therapeutisches Gestalten [Therapeutic sculpture]. Stuttgart, Germany: Verlag Freies Geistesleben &; Urachhaus; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mees-Christeller E, Denzinger I, Altmaier M, et al. Therapeutisches Zeichnen und Malen [Therapeutic drawing and painting]. Stuttgart, Germany: Verlag Freies Geistesleben &; Urachhaus; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majorek M, Tüchelmann T, Heusser P. Therapeutic eurythmy-movement therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a pilot study. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 2004; 10(1): 46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirchner-Bockholt M. Foundations of curative eurythmy. 2nd ed.Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris Books; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauschka-Stavenhagen M. Rhythmical massage as indicated by Dr. Ita Wegman. Spring Valley, NY: Mercury Press; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie J, Wilkinson J, Gantley M, et al. A model of integrated primary care: anthroposophic medicine. London: Department of General Practice and Primary Care, St Bartholomew's and the Royal London School of Medicine, Queen Mary, University of London; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidelines for good professional practice in anthroposophic medicine. International Federation of Anthroposophic Medical Associations. Last update: 2003.http://www.ivaa.info/anthroposophic-medicine/quality-control-in-am/guidelines-for-good-professional-practice-in-anthroposophic-medicine/ AccessedNovember20, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pütz H. Leitlinie zur Behandlung mit Anthroposophischer Kunsttherapie (BVAKT)® für die Fachbereiche Malerei, Musik, Plastik, Sprachgestaltung [Guideline for treatment with anthroposophic art therapy with the therapy modalities painting, music, clay, speech]. Filderstadt, Germany: Berufsverband für Anthroposophische Kunsttherapie e.V. [Association for Anthroposophic Art Therapy in Germany]; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eurythmy therapy guideline. Filderstadt, Germany: Berufsverband Heileurythmie e.V. (Eurythmy Therapy Association); 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vademecum of anthroposophic medicines. First English ed.Filderstadt, Germany: Medical Section of the School of Spiritual Science; International Federation of Anthroposophic Medical Associations (IVAA); Association of Anthroposophic Physicians in Germany (GAÄD); 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) and traditional medicinal products (TMP). Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM). Last update: 2012.http://www.bfarm.de/EN/drugs/2_Authorisation/types/pts/pts-node-en.html AccessedNovember20, 013 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamre HJ, Becker-Witt C, Glockmann A, et al. Anthroposophic therapies in chronic disease: The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS). Eur J Med Res 2004; 9(7): 351–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamre HJ, Kiene H, Glockmann A, et al. Long-term outcomes of anthroposophic treatment for chronic disease: a four-year follow-up analysis of 1510 patients from a prospective observational study in routine outpatient settings. BMC Res Notes. 2013; 6(1): 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for children with chronic disease: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. BMC Pediatr. 2009 Jun 19; 9: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for anxiety disorders: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. Clin Med Psychiatry 2009; 2: 17–31 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for asthma: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. J Asthma Allergy. 2009 Nov 24; 2: 111–28 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity: a two-year prospective study in outpatients. Int J Gen Med. 2010; 3: 239–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Glockmann A, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for chronic depression: a four-year prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2006 Dec 15; 6: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Long-term outcomes of anthroposophic therapy for chronic low back pain: a two-year follow-up analysis. J Pain Res. 2009; 2: 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamre HJ, Witt CM, Kienle GS, et al. Anthroposophic therapy for migraine: a two-year prospective cohort study in routine outpatient settings. Open Neurol J. 2010; 4: 100–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]