Abstract

Objective:

To develop and test the feasibility of a whole-systems lifestyle intervention for obesity treatment based on the practices of Ayurvedic medicine/ Yoga therapy.

Design:

A pre-post weight loss intervention pilot study using conventional and Ayurvedic diagnosis inclusion criteria, tailored treatment within a standardized treatment algorithm, and standardized data collection instruments for collecting Ayurvedic outcomes.

Participants:

A convenience sample of overweight/obese adult community members from Tucson, Arizona interested in a “holistic weight loss program” and meeting predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Intervention:

A comprehensive diet, activity, and lifestyle modification program based on principles of Ayurvedic medicine/yoga therapy with significant self-monitoring of lifestyle behaviors. The 3-month program was designed to change eating and activity patterns and to improve self-efficacy, quality of life, well-being, vitality, and self-awareness around food choices, stress management, and barriers to weight loss.

Primary Outcome Measures:

Changes in body weight, body mass index; body fat percentage, fat/lean mass, waist/hip circumference and ratio, and blood pressure.

Secondary Outcome Measures:

Diet and exercise self-efficacy scales; perceived stress scale; visual analog scales (VAS) of energy, appetite, stress, quality of life, well-being, and program satisfaction at all time points.

Results:

Twenty-two adults attended an in-person Ayurvedic screening; 17 initiated the intervention, and 12 completed the 3-month intervention. Twelve completed follow-up at 6 months and 11 completed follow-up at 9 months. Mean weight loss at 3 months was 3.54 kg (SD 4.76); 6 months: 4.63 kg, (SD 6.23) and 9 months: 5.9 kg (SD 8.52). Self-report of program satisfaction was more than 90% at all time points.

Conclusions:

An Ayurveda-/yoga-based lifestyle modification program is an acceptable and feasible approach to weight management. Data collection, including self-monitoring and conventional and Ayurvedic outcomes, did not unduly burden participants, with attrition similar to that of other weight loss studies.

Key Words: Obesity, integrative medicine, Ayurveda, yoga, whole systems, behavior change

摘要

目标: 基于阿育吠陀医学/瑜伽 疗法实践,发展对肥胖治疗的一 体化生活方式干预并进行可行性 测试。

设计: 采用传统和阿育吠陀诊断 纳入标准;在标准化治疗框架范 围内量身定制治疗方案;并通过 采用标准化数据收集设备收集阿 育吠陀结果,来进行一项治疗前 后减重的干预试点研究。

参与者: 通过方便选取方式选择 的、来自于亚利桑那州图森市社 区、对“整体减重计划”感兴趣 且符合预定纳入/排除标准的体 重超重/肥胖成年人士样本。

干预: 基于阿育吠陀医学/瑜伽 疗法的原则,制定一项综合性的 饮 食 、 活 动 和 生 活 方 式 调 整 计 划,同时对生活方式行为进行重 要的自我监控。 这项为期 3 个月 的 计 划 旨 在 改 变 饮 食 和 活 动 方 式 , 改 善 自 我 效 能 感 、 生 活 质 量、健康状况、生命力,以及在 食物选择、压力管理和减重障碍 方面的自我意识。

主要结果衡量指标: 体重变 化;BMI;身体脂肪百分比 (%); 脂肪质量/瘦肉质量;腰围/臀 围和比例以及血压。

次要结果衡量指标: 饮食和锻炼 自 我 效 能 感 量 表 ; 感 知 压 力 量 表;所有时间点的能量、胃口、 压力、生活质量、健康状况和计 划满意度的视觉模拟量表 (VAS)。

结果: 有二十二名成年人士亲自 到场参加了阿育吠陀筛选;其中 17 人进入到干预阶段,有 12 人 完成了为期 3 个月的干预。 在 6 个月时,有十二人完成跟进,在 9 个月时,有 11 人完成了跟进。 3 个月时的平均减重为 3.54 kg (SD 4.76);6 个月时: 4.63 kg,(SD 6.23),9 个月时: 5.9 kg (SD 8.52)。 整个研究过程中,自我报 告的计划满意度为 90%。

结论: 基于阿育吠陀/瑜伽的生 活方式调整计划是一种可接受且 可行的体重管理方法。 包括自我 监控、传统和阿育吠陀结果在内 的数据收集并不会对参与者造成 过度的负担,其消耗与其他减重 研究相类似。 在所有时间点,自 我报告的计划满意度都超过 90%。

SINOPSIS

Objetivo:

Desarrollar y probar la viabilidad de la intervención del estilo de vida integral para el tratamiento de la obesidad basándose en las prácticas de la medicina ayurvédica/del yoga terapéutico.

Diseño:

Estudio piloto sobre la intervención anterior y posterior a la pérdida de peso utilizando los criterios de inclusión de diagnóstico convencional y ayurvédico; tratamiento personalizado dentro de un algoritmo de tratamiento estandarizado y unos instrumentos de recogida de datos estandarizados para obtener los resultados ayurvédicos.

Participantes:

Una muestra conveniente de miembros adultos con sobrepeso/obesos de la comunidad de Tucson (Arizona) interesados en “un programa holístico para la pérdida de peso”, que reúnen criterios de inclusión/ exclusión predeterminados.

Intervención:

Un programa integral de modificación de dieta, actividad y estilo de vida basado en los principios de la medicina ayurvédica/del yoga terapéutico con un autocontrol considerable de los comportamientos del estilo de vida. El programa de tres meses ha sido diseñado para cambiar los patrones de alimentación y actividad y mejorar la autoeficiencia, calidad de vida, bienestar, vitalidad y autoconocimiento respecto a las elecciones alimentarias, gestión del estrés y obstáculos para la pérdida de peso.

Mediciones de resultados principales:

Cambios en el peso corporal; IMC; % de grasa corporal; masa corporal grasa/magra; perímetro y cociente de cintura/cadera y tensión arterial.

Mediciones de resultados secundarios:

Escalas de autoeficiencia de dieta y ejercicio; escala de estrés percibido; escalas visuales analógicas (EVA) de energía, apetito, estrés, calidad de vida, bienestar y satisfacción con el programa en todos los puntos cronológicos.

Resultados:

Veintidós adultos acudieron personalmente a la selección ayurvédica; 17 iniciaron la intervención y 12 terminaron la intervención de 3 meses. Doce completaron el seguimiento en 6 meses y 11 completaron el seguimiento a los 9 meses. El promedio de pérdida de peso en 3 meses fue de 3,54 kg (DE 4,76); 6 meses: 4,63 kg, (DE 6,23) y 9 meses: 5,9 kg (DE 8,52). La satisfacción autonotificada con el programa fue del 90 % durante todo el estudio.

Conclusiones:

Un programa de modificación del estilo de vida basado en el ayurveda/yoga es un enfoque aceptable y viable para el control del peso. La recogida de datos, incluyendo el autocontrol y los resultados convencionales y ayurvédicos, no supuso una carga excesiva para los participantes, con un índice de abandono similar al de otros estudios de pérdida de peso. La satisfacción autonotificada con el programa fue de más del 90 % en todos los puntos cronológicos.

INTRODUCTION

Prevalence

Obesity is an epidemic in the United States, with an estimated 37% of US adults diagnosed with obesity. Obesity is a primary causal factor in many diseases including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, stroke, and liver disease.1,2 The economic cost of obesity for the United States was estimated in 2008 to total approximately $147 billion.3,4 Conventional medical approaches have demonstrated limited success in the treatment or prevention of obesity.5–8 While some trials have shown that even moderate weight loss of 5% to 10% can significantly modify risk profiles for obesity-associated disease, novel approaches to treat obesity are needed.9–14

Implications of Prior trials

One novel approach to weight control that has shown some efficacy is yoga.15 A recent review suggested that for optimal weight loss, yoga postures should be practiced at least three times per week and be combined with dietary modification. Yoga practice, not contextualized within a larger medico-therapeutic paradigm, does not represent a complete therapeutic approach. Therapeutic yoga is enhanced by a broader treatment framework, and its therapeutic potential is maximized when combined with the principles and practices of Ayurvedic medicine.

Aim of the Current Project

The study was designed to test the feasibility, acceptability, and early efficacy of a whole-systems Ayurveda/yoga treatment approach for overweight/obese adults. It is the first published pilot feasibility study of a standardized Ayurveda/yoga intervention for weight loss that retains the principles of individualized care, making it simultaneously true to paradigm, feasible to replicate, and potentially generalizable to broader populations.

Development of the Protocol/Study design

The practice of Ayurvedic medicine entails the application of individualized, multimodal, and multi-target therapies and holds potential for the effective treatment of obesity. A 3-month intervention combining Ayurvedic diet, lifestyle modification, and yoga therapy was developed and piloted with 17 participants to determine feasibility and acceptability. This pilot study included Ayurvedic diagnostic categories and traditional diagnostic methods, including assessment of individuals' constitution/imbalance profiles, pulse and tongue analysis, and tailoring of therapeutic recommendations. The study design incorporated standardized dietary modification and a yoga program appropriate for predetermined Ayurvedic constitution/ imbalance profiles (Appendices A and B), as well as a biomedical diagnosis of obesity. Implementation of a standardized treatment algorithm with minor modifications on an individual basis is consistent with real-world Ayurvedic clinical practice in which treatment implementation is responsive to patient feedback. Tailored implementation of the standardized intervention according to participant feedback is a hallmark of the Ayurvedic clinical approach.16

Ayurvedic medical theory revolves around the interactional dynamics between three bioenergetic systems (doshas) with differing properties (vata, pitta, and kapha). Excess kapha dosha is the primary contributor to obesity. The treatment algorithm focused on treating aggravated kapha dosha as the root cause of obesity. The algorithm of care was developed based on the dual diagnosis of obesity and kapha aggravation, combined with one of two predetermined constitutional baselines (kapha dominant or pitta dominant/secondary kapha). An Ayurvedic approach goes beyond behavior change to focus on lifestyle change by tailoring the treatment to the physiology and psychoemotional profile of the individual, potentially increasing therapeutic impact and maximizing the accessibility and sustainability of change for the participant.

Ethics

This pilot feasibility study was approved by the University of Arizona (Tucson) Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

METHODS

Details of the Pilot

Participants were seen for an initial 1.5-hour consultation by an Ayurvedic clinician and twice monthly for follow-up visits during months 1 through 3 of the intervention. Ayurvedic diagnosis of imbalance was reevaluated at each visit. At regular bimonthly visits, an Ayurvedic clinician tailored the treatment plan to participants' individual needs within a standardized algorithm of care. Tailored advice included therapeutic recommendations regarding sleep, food cravings, daily routine, sensory input, relationships, and self-awareness. Participants attended three 75-minute kapha-pacifying yoga classes weekly and were instructed to complete this same yoga routine at home an additional three times per week (Appendix A). Participants received yoga instruction tailored to their functionality, using well-established props and modifications to make yoga postures accessible. A protocol for yoga teachers presenting the kapha-pacifying yoga sequence was developed to standardize the approach and promote an optimal teaching standard.

Instructions for dietary modification were provided to participants based on theories of Ayurvedic nutrition and the predominant food tastes and qualities that reduce elevated kapha dosha (Appendix B).17

Participants followed basic dietary guidelines, with minor modifications dictated by their constitution/ imbalance profiles. Participants charted food intake daily according to 16 taste and quality categories by number of servings per week. Participants also used this tool to increase their self-awareness around food choices. Researchers used completion of the self-monitoring tool to measure adherence. Uniquely designed instruments were also used to collect data on sensory input, changes in mood, primary relationships, and sleep patterns.

Recruitment and Selection

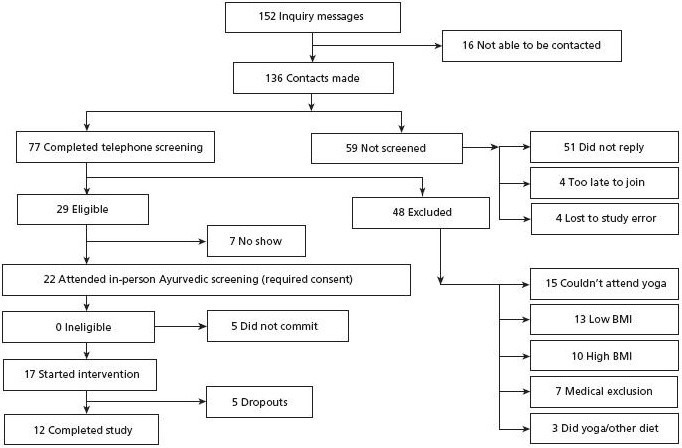

Participants were recruited by postings to university-affiliated listservs, including community health clinics and some public school settings; on television monitors in public areas of the university hospital; and through print fliers at university clinics. Twenty-two individuals attended an in-person screening for Ayurvedic diagnosis that required consent. Five refused the study, 17 began the intervention with all 17 doing the same yoga sequence, and 12 completed the 3-month program. The total sample of 12 ranged in age from 22 to 68 years, with 11 females and one male (Figure 1).

Figure.

Recruitment flowchart.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

The study applied dual-diagnoses screening for obesity according to both biomedical and Ayurvedic criteria, a mechanism which has been useful in recent studies.18 Study inclusion criteria were as follows: conventional eligibility defined obesity as body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 to 45 kg/m2 while Ayurvedic assessment focused on elevated kapha dosha, indicating metabolic dysfunction. All study participants were yoga naive. Ayurvedic medicine treats the imbalance of the individual while considering the influence of the constitution. The study design defined eligible participants as possessing either a kapha-predominant constitution or a pitta-predominant with secondary kapha constitution, both with a kapha imbalance. Though these constitutions differ, both constitutions are prone to kapha aggravation and attendant weight gain and thus would share similar physiological causality. Individuals with vata constitution were ineligible as weight gain for these individuals would, according to Ayurvedic theory, entail a causally distinct trajectory. The dietary guidelines and yoga regimen were designed to treat aggravated kapha dosha and were appropriate for both kapha-predominant and pitta/kapha constitutions. The dual diagnosis criteria caused no additional loss of participants in the screening phase. Exclusion criteria included insulin-dependent diabetes, arthritis or osteoporosis compromising functionality, current cardiovascular disease, issues with balance/equilibrium or mobility, or yoga practice within the last 2 years.

Process Evaluation

Sociodemographic characteristics of completers vs dropouts were collected. The two categories were comparable in all areas, with the exception of completers being approximately 6 years younger on average (Table 1). Some weight-loss trials have indicated that dropouts are younger on average. This program may appeal to younger participants, addressing one variable associated with weight loss intervention attrition. All five dropouts indicated via contact with study staff that their reason for not completing the program was due to scheduling conflicts related to attendance at three-times-weekly yoga classes.

Table 1.

Comparison of Socio-demographic Fata for Completers vs Dropouts

| BMI | Age | Dosha | Ethnicity | Education | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completers (12) | 33.58 | 41.33 | P8/K4 | 5 W/3 H/2 AA/2 NA | HS +4.5 y |

| Dropouts (10) | 33.60 | 47.00 | P8/K2 | 4 W/5 H/1 NA | HS +4.2 y |

Abbreviations: AA, African-American; HS, high school; H, Hispanic; NA, Native American; W, white.

Adherence

Two yoga teachers alternated teaching the yoga classes per a manual developed by the principal investigator. The lead yoga instructor had many years of formal training in both yoga and Ayurveda and more than a decade of teaching experience. The second yoga teacher was also certified, had been teaching for 3 years, and attended a number of tutorial sessions with the developer of the yoga regimen to ensure comparability of technique and verbal instruction in all yoga classes. Attendance logs for yoga classes were maintained. Adherence to the study protocol, including standardized and tailored dietary modification, was tracked through clinical notes and patient self-report. Thrice weekly yoga classes, home yoga practice, and bimonthly consultations with an Ayurvedic medicine practitioner were well tolerated. Participants reported that the Ayurvedic outcome instruments promoted self-awareness around food and lifestyle choices. Study attrition was 29.5%, similar to that of other weight-loss studies.19

MEASURES

Topographical Data Collection

The research design strategy for this pilot feasibility study involved the collection of both conventional anthropometric and psychosocial outcomes, as well as Ayurvedic outcomes, in order to create a topographical data set. We suggest the concept of topographical clinical outcomes data as a reference to the following definition of topography: “description or analysis of a structured entity, showing the relations among its components.”20 This method of collecting clinical outcomes may also be usefully related to the anthropological notion of thick description,21 which implies intensive and dense depictions and explanations of context that may provide insight into the evolution and development of the phenomenon under study. In the case of this feasibility study, the dual-diagnosis design provides a diagnostic rubric that informs the development of the standardized intervention, while the psychosocial context of each patient and their incremental response to treatment inform the individualization of the intervention as it proceeds. In this manner, the patient population stands as a cohesive whole, while tailored treatment features provide the opportunity to maximize patient response to and compliance with the intervention. Intensive collection of clinical outcomes data provides insight into individualized features of the treatment regimen, while the density of data on any given feature of the intervention or treatment response allows for maximal interpretation of outcomes in relation to a predetermined causal model.

Assessment

Ayurvedic treatment guidelines were standardized, and unique Ayurvedic outcomes instruments were developed. Inclusion of Ayurvedic diagnostic categories, like tongue and pulse analysis, as well as other outcomes relevant to Ayurvedic diagnosis, were essential to maintaining model validity and ensuring maximum benefit from the intervention. Table 2 shows the timing and content of study assessments.

Table 2.

Study Data Collection Measures and Time Points for Collection

| Measure | Baseline | Wk 1 | Wk 2 | Wk 3 | Wk 4 | Wk 5 | Wk 6 | Wk 7 | Wk 8 | Wk 9 | Wk 10 | Wk 11 | Wk 12 | 6 mo | 9 mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | × | ||||||||||||||

| Health history | × | ||||||||||||||

| BMI; body fat %, lean mass, waist/hip circumference and ratio; BP | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||

| Constitution questionnaire | × | × | × | ||||||||||||

| Imbalance questionnaire | × | × | × | ||||||||||||

| Ayurvedic pulse/tongue analysis; clinical notes | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||

| Eating self-efficacy | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Exercise self-efficacy | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Perceived stress scale | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Treatment tailoring | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Food wheela,b | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Mood/affecta | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Yoga logc | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Sleep factors | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Sensory stimuli | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Relationships | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | × | × | × | ||||||||||||

| Exit interview | × | × |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure.

Ayurvedic self-report instruments were filled out weekly, photographed, and images emailed to study personnel for logging.

Food wheel submission was logged and provided dietary adherence data.

Yoga class attendance data were collected and compiled monthly.

Adverse events were collected at all data collection time points.

Adherence

Yoga adherence was defined as frequency of yoga class attendance combined with frequency of self-reported home practice. Dietary adherence was defined as frequency of logging dietary intake using the Ayurvedic diet protocol.

Outcome Measures: Conventional Anthropometrics

The primary outcome of the study was change in weight, measured on both medical and calibrated electronic Tanita scales (Arlington Heights, Illinois). Other outcomes included changes in BMI, body fat percentage (Tanita scale), and waist/hip circumferences and ratio (Gulick tape measure; Collins Medical Equipment, Fairfield, Connecticut).

Ayurvedic Outcomes: Diet, Daily Routine, and Lifestyle

Ayurvedic outcomes were assessed to depict changes in Ayurvedic constitution/imbalance profiles over time. Instruments were designed to capture data in five lifestyle-related areas identified by Ayurveda as potential contributors or impediments to weight loss: (1) dietary intake based on food qualities, including cravings and aversions; (2) changes in mood associated with kapha aggravation; (3) sensory input; (4) frequency, content, and intensity of yoga, breathing and meditation; and (5) changes in relationship quality and interaction. Data were also collected via visual analog scales (VAS) on appetite, energy, and self-awareness to represent nonspecific effects of the intervention or overall benefit.

Psychosocial Outcome Measures

Pre and post data were collected on self-efficacy in regulating diet and exercise using modified versions of Bandura's self-efficacy scales, Perceived Stress Scale, and VAS for quality of life and well-being. Weight loss, self-efficacy, perceived stress, and quality of life/well-being were also collected at 6 and 9 months to determine the durability of the program effects.

RESULTS

Adherence

Mean adherence to weekly food wheel completion was 54% out of a possible 12 total weeks. Mean adherence to yoga classes and home practice combined was 58% out of a possible 72 total practice sessions. This demonstrates feasibility for implementing the intervention per protocol. Higher adherence was associated with greater weight loss. High adherers were defined as participants above the mean (55%). Individuals having ≥55% adherence to both diet and yoga protocols demonstrated a mean weight loss of 6.2 kg over 3 months as compared to individuals with low adherence to both diet and yoga who demonstrated a mean weight gain of .9 kg at 3 months. High adherers lost an average of 6.4% of their baseline body weight at 3 months, 10.6% at 6 months, and 11.6% at 9 months. High adherence vs low adherence produced a mean 7.1-kg difference in weight loss at 3 months and a 4.63-kg difference at 6 months.

Perception of the Program: Benefits and Challenges

No adverse events associated with the dietary changes or yoga practices were reported. The nonspecific effects or overall benefits of the program and frequency of responses are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participant Spontaneous Reports of Program Benefits and Challenges (N=12)

| Benefits | No. of times cited |

|---|---|

| Reduced stress, more relaxed, calmer | 9 |

| Overall fitness, stronger | 9 |

| More aware of diet and response to foods | 8 |

| Improved well-being, positive outlook | 7 |

| Flexibility/balance | 5 |

| Increased self-awareness | 5 |

| Establishing routine, sustainable changes | 4 |

| Learning about yoga, Ayurveda | 4 |

| Weight loss, improved appearance | 3 |

| More energy | 3 |

| Decreased pain, stiffness, aches | 2 |

| Total unique times benefits cited | 59 |

| Challenges | No. of times cited |

|---|---|

| Changes to diet and habits | 10 |

| Yoga poses | 8 |

| Scheduling | 4 |

| Data collection | 3 |

| Time commitment | 2 |

| Total unique times challenges cited | 27 |

Psychosocial Measures

On average, self-efficacy around dietary change and exercise improved in all categories from baseline to 3 months with continued improvement at 6 months and a trend toward minimal decline at 9 months. Changes in perceived stress improved from baseline to 3 months and ability to maintain positive perceptions/ outlook was sustained at 6 and 9 months. Participant self-report of stress indicated reduced stress level at every time point after enrollment. Participants also reported increased energy, well-being, quality of life, and self-awareness at 3 and 6 months, with measures that remained above baseline values at 9 months. Satisfaction with the program was consistently above 90% at all time points assessed. Complete response data were available at 3 and 6 months and for 11 of 12 participants completing the study at 9 months.

Conventional Measures: Weight loss, Body Fat Percentage, and Body Mass Index Change

Evidence supporting the preliminary efficacy of the intervention for weight control is presented in Table 4. Moderate reductions in weight, body fat percentage, and BMI from pre to post measures were demonstrated. Small to moderate reductions in waist circumference and waist:hip ratio were also demonstrated. Participants who reached a threshold of 3% weight loss during the 3-month intervention continued to lose weight at 6 and 9 months.

Table 4.

Conventional Weight Loss Outcomes

| N=11a | Weight loss 3 mo, kg | Weight loss 6 mo, kg | Weight loss 9 mo, kgb | % Weight loss 3 mo | % Weight loss 6 mo | % Weight loss 9 mob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | −3.54 | −4.63 | −5.90 | 3.6% | 4.9% | 6% |

| SD | 4.76 | 6.23 | 7.75 | .045 | .068 | .087 |

| N=11a | BMI pre | BMI 3 mo | BMI 6 mo | BMI 9 mob | Body fat % pre | Body fat % 3 mo | Body fat % 6 mo | Body fat % 9 mob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 33.2 | 31.9 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 43.18 | 39.43 | 39.72 | 39.36 |

| SD | 5.23 | 4.84 | 5.56 | 5.37 | 5.59 | 4.72 | 6.67 | 6.12 |

One participant excluded from weight loss data due to surgical complications unrelated to study.

All participants with complete data collection at 3- and 6-mo time points, one lost to follow-up at 9 mo (N=10).

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

DISCUSSION

Twelve participants completed this 3-month, single-arm, pilot feasibility study of a whole-systems Ayurvedic medicine/yoga therapy intervention for obesity at the University of Arizona in spring 2012. The design integrated a combined strategy of comprehensive lifestyle change and ritualized self-awareness practices. The intervention included standardized Ayurvedic dietary guidelines with tailoring to participants' Ayurvedic constitution/imbalance profiles. Three 75-minute Kapha-pacifying yoga classes were provided weekly. The implementation, sequencing, and specific instructions for the yoga sequence were developed to pacify kapha dosha according to Ayurvedic medical principles. Standardized Ayurvedic outcome instruments were developed for this study to maintain model validity and explore connections between physiological and psychosocial aspects of Ayurvedic treatment. The sustainability of the lifestyle changes was measured at 6 and 9 months. Continued weight loss and maintenance of improved psychosocial outcomes were established. Data on the sustainability of change for an Ayurvedic medicine/ yoga therapy lifestyle intervention are promising for future applications of similar components and study designs. Initial outcomes data indicate that effects are durable over time.

LIMITATIONS

The small sample size of this pilot study means that this study was not powered to detect statistical significance for quantitative outcomes. The Ayurvedic data collection instruments were newly developed for this study and are in the process of being reviewed, refined, and validated. Data collection and protocol adherence were estimated to be 65%—less than ideal. We anticipate that retention and adherence rates will increase with refinement of the instruments and protocol, including flexibility in yoga class scheduling, based upon participant feedback. Another limitation of the study was the short duration of the intervention. On exit interview, participants cited the desirability for post-intervention support groups to facilitate continued diet and lifestyle changes and booster yoga classes during follow-up (>3 months) to promote maintenance of home yoga practice. We plan to incorporate these components into future protocols and expand the intervention period.

CONCLUSION

This whole-systems Ayurvedic medicine and yoga therapy pilot intervention combined comprehensive lifestyle change and ritualized self-awareness practices into an alternative diet and activity modification approach that was effective for weight loss in over-weight/obese adults. This is the first published study to test the feasibility of a tailored, whole-systems Ayurveda/yoga weight loss intervention and present promising preliminary results in terms of conventionally recognized outcomes for assessing obesity. This pilot study is also the first to collect standardized Ayurvedic outcomes in an academic medicine setting in the United States. Preliminary data analysis suggests that a whole-systems Ayurveda/yoga approach to obesity offers an acceptable, noninvasive, and low-risk treatment option for obesity, although a longer-term intervention is warranted. More in-depth analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes, as well as indications of the sustainability of behavioral change that supports weight management, are promising and are being submitted for publication. Planning for a larger, randomized controlled trial is underway.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH-NCCAM grant No. T32-AT001287, the Arizona Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research Training Program. The authors wish to thank Drs Cheryl Ritenbaugh and Scott Going; Charis Domador, research assistant; and Dr Amy Howerter, research specialist.

Appendix A: Yoga Sequence for Weight Loss Study (In-class and Home Practice)

In all poses, we emphasized the light quality via suspension, distance from the ground, lifting in limbs and trunk. As ses sions progressed, we focused on lengthening the duration of balance poses, increasing endurance in strength poses, more rapid transitions between poses, and maintaining longer pose sequences in a continuous flow. We de-emphasized the slow, static, grounded, heavy, dense, and cool properties of kapha dosha and increased oppositional qualities through speed of movement and raising heat in the body.

Beginning in week 5 of the study, we added sun salutations to the beginning of the sequence as increased strength and endurance of participants made this practice accessible. The number of sun salutation repetitions was gradually increased over time to a maximum of four, preceding the start of the regular yoga sequence.

Participants were instructed to practice Ujjayi pranayama throughout the yoga sequence, and they were provided with a manual of all yoga poses, including photos.

Mountain

Mountain with arms overhead

Mountain with bound arms overhead

Mountain with eagle pose arms

Mountain with cow face arms

Mountain with reverse Namaste arms

Tree pose

Triangle

Warrior II

Extreme side angle

Half moon pose

Mountain

Chair

Straight-legged Standing forward bend

Plank

Upward dog

Downward facing dog

Warrior I

Wide legged standing forward bend

Downward facing Dog

Straight-legged standing forward bend

Sitting on heels, toes bent under

Hero

Twisted hero

Seated twist

Spinal twist seated on floor

Upward facing head to knee

Wide legged seated forward bend

Cobbler pose

Camel pose

Reclining hand to foot pose

Bridge pose

Alligator twists

Legs up the wall (hips on blanket)

Corpse pose: 10 minutes

5 minutes So/Hum meditation

Appendix B: Ayurvedic Dietary Guidelines for Weight Loss Study

Emphasize lightly cooked or raw vegetables, whole grains and fresh fruits, and light proteins (legumes, fish, or poultry).

Please avoid sweet, salty, oily, heavy, rich, and dense foods. Gradually work toward eliminating processed and packaged foods, white flour and sugar, alcohol, and dairy.

Drink four to six 8-oz glasses of room-temperature water per day. Drink one immediately upon waking and one glass with every meal. Please do not put ice in your drinks.

When eating, the stomach should be filled with 1/3 food, 1/3 water and 1/3 space. Eat your biggest meal at midday.

Separate fruit from other foods by 30 minutes and do not eat meat and dairy together.

Please note any craving or avoidance of certain foods on your food wheel and your lifestyle change log.

Approach food intake as an act of self-love. Don't eat when feeling emotional or upset. Take a few minutes to focus on your breathing. Consider your food as the source of your energy and vitality. Eat with awareness, focusing on the tastes and qualities of the foods you are eating and how they make you feel.

Cook at least 5 meals at home per week and use the following spices: cumin, coriander, fennel, cardamom, ginger, cinnamon, turmeric, basil, oregano, mustard seeds, garlic, and black pepper.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and had no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Rioux, Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico, School of Medicine, Albuquerque (Dr Rioux), United States.

Cynthia Thomson, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson (Dr Thompson), United States.

Amy Howerter, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona (Dr Howerter), United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Obesity Education Initiative: clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. 1998. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf AccessedDecember16, 2013

- 2.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006; 56(5): 254–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. http://www.surgeon-general.gov/library/calls/obesity/CalltoAction.pdf.pdf AccessedDecember16, 2013 [PubMed]

- 4.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W.Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer- and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009; 28(5): w822–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strychar I.Diet in the management of weight loss. CMAJ. 2006; 174(1): 56–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shick SM, Wing RR, Klem ML, McGuire MT, Hill JO, Seagle H. (April1998). Persons successful at long-term weight loss and maintenance continue to consume a low-energy, low-fat diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998; 98(4): 408–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate DF, Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Wing RR.Long-term weight losses associated with prescription of higher physical activity goals. Are higher levels of physical activity protective against weight regain? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 85(4): 954–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rucker D, Padwal R, Li SK, Curioni C, Lau DC.Long term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: updated meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007; 335(7631): 1194–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346(6): 393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008; 371(9626): 1783–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344(18): 1343–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasanisi F, Contaldo F, de Simone G, Mancini M.Benefits of moderate sustained weight loss in obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2001 Dec; 11(6): 401–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, Ballaux D.What is the relationship between risk factor reduction and degree of weight loss? Eur Heart J Suppl. 2005; 7(Suppl L): L1–26 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okura T, Nkata Y, Ohkawara K, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on metabolic syndrome improvement in response to weight reduction. Obesity. 2007; 15(10): 2478–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rioux J, Ritenbaugh C.Narrative review of yogic interventions including weight-related outcomes. Altern Ther Health Med. 2013; 19(3): 46–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rioux J.A complex, nonlinear dynamic systems perspective on Ayurveda and Ayurvedic research. J Altern Complement Med. 2012; 18(7): 709–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lad V.Textbook of Ayurveda, vol. 1: fundamental principles. Albuquerque, NM: Ayurvedic Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritenbaugh C, Hammerschlag R, Calabrese C, et al. A pilot whole systems clinical trial of traditional Chinese medicine and naturopathic medicine for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders. J Altern Complement Med. 2008; 14(5): 475–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDoniel SO, Hammond RS.A 24-week randomized controlled trial comparing usual care and metabolic-based diet plans in obese adults. Int J Clin Pract. 2010; 64(11): 1503–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The American Heritage dictionary of the English language, Fourth ed Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geertz C.Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture. : The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books; 1973:3–30. [Google Scholar]