Abstract

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple susceptibility loci for immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN), the most common form of glomerulonephritis, implicating independent defects in adaptive immunity (three loci on chromosome 6p21 in the MHC region), innate immunity (8p23 DEFA locus, 17p23 TNFSF13 locus, 22q12 HORMAD2 locus), and the alternative complement pathway (1q32 CFH/CFHR locus). In geospatial analysis of 85 populations, a genetic risk score based on the replicated GWAS loci is highest in Asians, intermediate in Europeans, and lowest in Africans, capturing the known difference in prevalence among world populations. The genetic risk score also uncovered a previously unsuspected increased prevalence of IgAN-attributable kidney failure in Northern Europe. The IgAN risk alleles have opposing effects on many immune-mediated diseases, suggesting that selection has contributed to variation in risk allele frequencies among different populations. Incorporating genetic, immunologic, and biochemical data, we present a multistep pathogenesis model that provides testable hypotheses for dissecting the mechanisms of disease.

Keywords: adaptive immunity, innate immunity, alternative complement system, IgA glycosylation, GWAS, IgA nephropathy

INTRODUCTION

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common type of glomerulonephritis worldwide. It was recognized as a separate category of glomerulonephritis when Berger applied the immunofluorescence staining technique to renal biopsy in 1968 (1). Much progress has occurred in understanding immunologic and biochemical defects underlying IgAN (most recently reviewed in Reference 2). This review focuses on recent genetic studies of IgAN, which have enabled reinterpretation of classic clinical and epidemiologic findings and have led to the formulation of a new pathogenesis model.

CLINICAL FEATURES

IgAN manifests with recurrent episodes of gross hematuria, microscopic hematuria, or acute nephritic syndrome, which often coincide with mucosal infections (3). The peak incidence is in the second and third decades of life. A kidney biopsy is required for diagnosis and is characterized by mesangial immunodeposits of IgA1 with C3 and occasionally IgG or IgM (4). The alternative pathway components C3 and properdin (P) and the membrane attack complex (C5b--9) are generally detected in the mesangial deposits, whereas the classical pathway components C1q and C4 are usually absent. Serum concentrations of C3 and other complement proteins are typically normal, suggesting an alternative pathway is activated in situ in the kidney (5).

Hematuria is typical and often includes episodes of macroscopic bleeding that coincide with mucosal infections, including those of the upper respiratory tract or digestive system. Proliferation of mesangial cells and expansion of extracellular matrix are found in patients with mild clinical disease, but progressive glomerular and interstitial sclerosis leads to end-stage kidney failure in 20%--40% of patients within 20 years after diagnosis (6). The predictors of poor renal outcome in IgAN include higher levels of proteinuria, histology grade, systolic blood pressure, and degree of renal function impairment at diagnosis, as well as lower albumin and hemoglobin levels at the time of biopsy (7--10). Interestingly, IgAN recurs in up to 50% of renal allografts (11); however, immune deposits in a kidney transplanted from a donor with subclinical IgAN into a patient with non-IgAN renal disease clear within several weeks (12). These findings suggest that the cause of IgAN is extrarenal and is most likely due to abnormalities in the circulation.

IgA1 GLYCOSYLATION DEFECTS

New insight into pathogenesis emerged from the analysis of the glycosylation of IgA1 (13, 14). Owing to significant differences between the human and rodent IgA systems, human studies were critical in elucidating the role of IgA1 glycosylation defects. Whereas rodents express only one type of IgA, humans and hominoid primates have two IgA subclasses, IgA1 and IgA2 (15). IgA1 is the predominant subclass in circulation while IgA2 is more abundant in mucosal sites. IgA1 has a unique hinge region between the first and second constant-region domains that has multiple serine and threonine residues. This segment is the site of attachment of up to six O-linked glycan chains consisting of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and a β1,3-linked galactose, both of which may be sialylated (16--19). O-linked glycans are synthesized in a step-wise manner, beginning with attachment of GalNAc to serine or threonine. The carbohydrate composition of the O-linked glycans on normal human circulatory IgA1 is variable, with the largest glycan being a tetrasaccharide consisting of GalNAc, Gal, and two sialic acid residues. In patients with IgAN, immune complexes in circulation and in kidney deposits contain IgA1 with galactose-deficient O-linked glycans (Gd-IgA1) (20--23). Aberrant glycosylation in IgAN affects only IgA1 and not other glycoproteins with O-linked glycans, suggesting a specific defect (14, 24). The pathogenicity of Gd-IgA1 is further supported by the finding that among patients with IgA1 myeloma, only those with Gd-IgA1 develop IgA1-associated immune-complex glomerulonephritis (25, 26). Moreover, our studies have demonstrated that IgA1-producing cells are the source of the abnormal IgA1 glycoforms (27). IgA1-producing cells from IgAN patients have multiple enzymatic defects that shift the IgA1 glycosylation pathway toward production of Gd-IgA1, in which some of the O-glycans are galactose deficient (27). These data imply regulatory defects upstream of the glycosylation enzymes in IgAN.

The measurement of Gd-IgA1 has been facilitated by the development of a sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a GalNAc-specific lectin that can establish normative values in large populations (28). Studies using this assay have shown that levels of Gd-IgA1 in supernatant of IgA1-producing cells and in serum of the matching donors are highly correlated, and 50%--78% of IgAN patients have serum Gd-IgA1 levels above the 95th percentile of healthy controls (28). This finding has been reproduced in European, African-American, and Asian populations, identifying abnormal IgA1 glycosylation as a common defect underlying the development of disease (29--31).

FAMILY STUDIES

Prior studies have demonstrated a range of immunologic defects in asymptomatic family members of IgAN patients, including increased production of IgA1, IgM, and cytokines at baseline and after antigenic stimulation (32, 33). More recently, systematic family studies have shown that elevated Gd-IgA1 levels are heritable, with 25%--33% of asymptomatic family members displaying levels that are just as elevated as the patients’ (34, 35). These findings have been replicated, implicating abnormal IgA1 glycosylation as a consistent inherited risk factor across major ethnicities (29, 30). The heritability of Gd-IgA1 is >50% and is not explained by total IgA1 levels, indicating independent genetic control (34).

Gd-IgA1 is usually detected in complex with IgG or IgA1 antibodies specific for the aberrantly glycosylated hinge regions (36), suggesting that a second hit (viral or somatic) leads to production of antiglycan antibodies and results in formation of immune complexes that ultimately deposit in the kidney. IgAN patients also have a more pronounced IgG responses to mucosal antigens (37), perhaps enhancing the antiglycan IgG response.

Finally, although most cases of IgAN occur as sporadic disease, familial aggregation of biopsy-proven IgAN has been widely reported (38, 39). Studies have also shown increased prevalence of IgAN in isolated populations, implicating founder effects leading to disease (40, 41). Linkage studies have found multiple susceptibility loci for familial disease, but underlying genes have not been identified to date, likely owing to genetic heterogeneity and small family size (42, 43).

GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION STUDIES

There are three published genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of IgAN. The first GWAS, performed in 533 European cases and 4,980 public controls, identified a significant association at the major histocompatibility (MHC) locus (44). We performed a GWAS in 3,144 cases and 2,822 controls, with discovery in Han Chinese and follow-up in Asian and European cohorts, in which we identified five susceptibility loci for IgAN. These included three distinct loci in the MHC region as well as the CFH/CFHR locus and the HORMAD2 locus (45). We have now extensively replicated these findings in 12 Asian and European cohorts including a total of 10,755 individuals (46). Another recent GWAS in Han Chinese cohorts of 4,137 cases and 7,734 controls identified two additional loci, DEFA and TNFSFR13 (47). A summary of the GWAS loci discovered to date, including each one’s approximate effect size, population frequency, and potential role in IgAN pathogenesis, is provided in Table 1. Although for many of these loci, the underlying causal variants are yet to be identified, the GWAS findings have generated new insight into the pathogenesis of IgAN.

Table 1.

New immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) susceptibility loci discovered in genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

| SNPs independently associated with IgAN (ancestral allele)a |

Risk allele: approximated effect sizebb |

Risk allele frequencies (Africans-- Europeans-- Asians)c |

Genes in the region | Potential role in IgAN pathogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within the MHC region | ||||

| 6p21: rs9275596 (T) | T: ~50% risk increase | 63%−67%−87% | HLA-DRB1 DQA1, -DQB1 | This region contains some of the most polymorphic MHC-II molecules involved in antigen presentation. Based on conditional GWAS analyses, this region harbors at least three genome-wide significant haplotypes independently associated with IgAN, implying causal associations of several classical HLA-DR or -DQ alleles. The DRB1*1501-DQB1*602 haplotype exhibits the strongest protective effect against IgAN; notably, this haplotype is also strongly protective against type 1 diabetes. |

| 6p21: rs9275224 (A) | G: ~40% risk increase | 47%−52%−62% | ||

| 6p21: rs2856717 (C) | C: ~30% risk increase | 69%−63%−81% | ||

| 6p21: rs9357155 (G) | G: ~20% risk increase | 94%−83%−85% | PSMB8, PSMB9, TAP1 TAP2 | TAP2, TAP1, PSMB8, and PSMB9 are interferon-regulated genes involved in antigen digestion and processing for presentation by MHC-I molecules; PSMB8 expression is increased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from individuals with IgAN. |

| 6p21: rs1883414 (T) | C: ~20% risk increase | 85%−67%−80% | HLA-DPB2, -DPB1, -DPA1, and COL11A2 | This region contains MHC-II molecules involved in antigen presentation. The exact involvement in the pathogenesis of IgAN is presently not clear. |

| Outside the MHC region | ||||

| 1q32: rs6677604 (G) | G: ~40% risk increase | 53%−77%−91% | CFH and CFHR gene cluster | The derived allele (A) is a perfect proxy for a common deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3 genes. This deletion is protective against IgAN and AMD and promotes suppression of the alternative complement pathway. The inhibitory effect on the complement system likely confers protection against glomerular inflammation from the deposited immune complexes. |

| 8p23: rs2738048 (T)d | C: ~30% risk increase | 19%−29%−35% | DEFA gene cluster | DEFA genes encode α-defensins, which are natural antimicrobials. Involved in the innate immune defense against infections, α-defensins have variable copy numbers that are related to the level of protein expression. The relationship of DEFA copy numbers to the risk of IgAN is not clear. |

| 22q12: rs2412971 (A) | G: ~30% risk increase | 21%−62%−70% | HORMAD2, MTMR3 LIF, OSM, GATSL3 SF3A1 | The derived allele (G) conveys increased risk of IgAN but protection against inflammatory bowel disease and is also associated with higher serum IgA levels in IgAN. The two nearby cytokines, LIF and OSM, may promote IgA production by stimulated B cells. Not much is known about the structure and function of the HORMAD2 and MTMR3 genes in this region. |

| 17p13: rs3803800 (A)d | A: ~20% risk increase | 79%−22%−28% | TNFSF13, MPDU1 EIF4A1, CD68, TP53 SOX15 | TNFSF13 encodes APRIL, a TNF ligand involved in B cell development, response to mucosal antigens, and production of IgA in the gut-associated mucosal lymphoid tissues. Patients with IgAN have elevated serum levels of APRIL and higher IgA levels. |

| Gene × gene interactions | ||||

| 1q32 × 22q12 interaction | -- | -- | -- | The protective effect of the ancestral allele at chromosome 22q12 is reversed among homozygotes for the CFHR3/1 deletion (1q32). The biological basis of this interaction is presently not clear. |

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; APRIL, a proliferation-inducing ligand; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

Ancestral allele defined by comparison of human to chimpanzee sequence.

Approximate effect sizes based on the largest available analyses of GWAS discovery and replication cohorts combined.

Allelic frequencies expressed as percentages, based on the HapMap-III data. Notably, all risk alleles with larger effect sizes (ORs 1.3–1.5) are most frequent in Asians and least frequent in Africans.

These loci have not yet been replicated in European cohorts (not included in the genetic risk score).

The MHC Loci (Chromosome 6p21)

All three GWAS have identified multiple signals within the MHC region. Owing to the complexity of the MHC haplotype structure, its significant variability among world populations, and the relatively sparse coverage provided by standard GWAS SNP-chips, the origin of the signals has not been precisely localized and will require higher-resolution mapping.

In our study, the strongest association was observed in the region that included the HLA-DQB1, -DQA1, and -DRB1 genes. The association was supported by a large cluster of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the top SNP (rs9275596). Imputation of classical human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles identified a highly protective effect conferred by the DQB1*0602-DRB1*1501 haplotype (45). However, this region harbors some of the most polymorphic genes in the human genome and has a complicated haplotype structure. Not surprisingly, conditional analyses in larger cohorts have identified at least two other independent risk haplotypes within this region (46). The third GWAS, conducted exclusively in the Han Chinese cohorts, confirmed the strongest signal in this region, also represented by at least three SNPs. The presence of multiple modest-sized signals explains why prior association studies with older HLA typing methods had yielded contradictory results (48--50).

This interval has been implicated in many immune-mediated disorders that show clinical overlap with IgAN, such as celiac disease (51), IgA deficiency (52), and inflammatory bowel disease (53), but the IgAN-associated SNPs are distinct from (in equilibrium with) those associated with these disorders. The DRB1*1501-DQB1*0602 haplotype is common in the European and Asian populations and has been implicated in the risk of multiple disorders of immunity and response to environment: it has been associated with increased risk of multiple sclerosis (54), systemic lupus erythematosus (55), narcolepsy (56), and hepatotoxicity from COX2 inhibitors (57). The same haplotype is highly protective from type 1 diabetes mellitus (58).

The second independent locus within MHC contains the TAP1, TAP2, PSMB8, and PSMB9 genes and the PPP1R2P1 pseudogene. One of the top-scoring SNPs, rs2071543, is a missense variant (Q49K) in exon 2 of PSMB8. Interestingly, decreased PSMB8 expression has been detected in peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes in IgAN, providing independent evidence that this may be the causal gene (59). The TAP2 and PSMSB8/PSMB9 genes have been implicated in antigen processing and presentation and play an important role in modulation of cytokine production and cytotoxic T cell response. Nonetheless, our recent replication study detected heterogeneity at this locus, likely due to a recombination hotspot directly centered over the TAP2 gene, which may perturb LD patterns between tag-SNPs and causal variants (46). Therefore, higher density of SNP coverage on either side of the recombination hotspot will be needed to guide future replication and fine mapping efforts.

The third independent locus within MHC is centered over the region of the HLA-DPA1, -DPB1, -DPB2, and COL11A2 genes. This region has been associated with increased risk of systemic sclerosis stratified for anti-DNA topoisomerase I or anticentromere autoantibodies (60), but the risk alleles associated with this phenotype are not in LD with any of the IgAN risk alleles. Presently, the involvement of this region in the pathogenesis of IgAN is not clear.

The CFH and CFHR Gene Cluster (Chromosome 1q32)

The association region identified on chromosome 1q32 encodes critical regulators of the complement system and has a complex genomic organization; it contains CFH and five CFH-related genes that have a high level of sequence similarity to CFH (61). Factor H (FH), encoded by the CFH gene, is the key inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway. It accelerates the decay of C3 convertase by binding C3b and targeting it for Factor I--mediated degradation. Structurally, FH is composed of 20 domains encoded by highly repetitive short consensus repeats (SCRs). The C terminus of the molecule (recognition domain) is responsible for binding to cellular surfaces, and the N terminus (regulatory domain) mediates C3b binding and inhibition. In healthy individuals, FH is active both in the fluid phase (as a circulating molecule in the serum) and in the surface-bound form (coating endothelial cells to prevent complement-mediated damage). Similar to CFH, the CFH-related genes are composed of a variable number of SCRs and have related binding properties. These genes likely arose by segmental duplications of CFH during evolution. Notably, the presence of highly repetitive sequences makes this area particularly prone to copy-number variation (CNV) due to nonallelic homologous recombination with intra- and intergenic breakpoints. Because each SCR unit is encoded by a single exon, duplications, insertions, and deletions of individual exons (a process described as exon shuffling) likely contributed to the final organization of this gene cluster.

The loss-of-function mutations in CFH have been well studied and generally result in increased activation of the alternative pathway (62). Because microvascular structures are particularly prone to complement-mediated injury, FH defects frequently result in either glomerular or retinal disease. Mutations of the N terminus (regulatory domain) result in complement-mediated mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, such as C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN), or dense-deposit disease (63). Mutations of the C terminus (surface-binding domain) result in the clinical picture of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, a systemic thrombotic disorder of endothelial injury with renal and hematologic manifestations. Because such deleterious alleles cause serious renal and systemic disease, they negatively impact reproductive fitness and thus are quickly eliminated from the population by purifying selection. Accordingly, their frequency is extremely low in human populations. However, several common variants in CFH have also been associated with human disease. The best example is the Y402H variant in SCR-7 of FH, which predisposes to age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (64). AMD is characterized by excessive complement activation with retinal deposition of alternative pathway proteins such as FH, C3, C5, and membrane attack complex (MAC), manifesting as drusen on fundoscopic eye exam. The harmful effect of Y402H variant in AMD is substantial, yet this variant is maintained at high frequency in human populations, implying this phenotype has a low impact on reproductive fitness.

The top SNP associated with IgAN, rs6677604, resides in intron 12 of the CFH gene. However, the minor allele of this SNP is in perfect LD with a common inherited CNV in this area: a deletion of two contiguous genes, CFHR3 and CFHR1 (CFHR3,1-del). Heterozygous individuals carrying CFHR3,1-del have a >40% reduction in the risk of IgAN. Interestingly, CFHR3,1-del has previously been associated with decreased risk of AMD (65), although defining its protective effect has been complicated by the strong effect of nearby Y402H (66). In contrast, this deletion accounts for all of the IgAN GWAS signal on chromosome 1q32, and Y402H has practically no effect on disease risk. More recently, a rare partial duplication of CFHR3 and CFHR1 leading to formation of a CFHR3-1 hybrid gene has also been reported to cause an inherited form of C3GN (67). These findings support the hypothesis of a dosage effect of CFHR1 and CFHR3: whereas lower copy number is associated with renal protection, additional copies increase the risk of complement-mediated glomerular disease. Nevertheless, CFHR3,1-del may represent a double-edged sword: though protective against AMD and IgAN, CFHR3,1-del has been associated with anti-FH antibody formation causing rare acquired forms of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (68, 69).

The above disease associations clearly imply an important functional role of the CFHR3 and CFHR1 genes. Unfortunately, not much is known about the mechanism of action for these peptides. From the genetic standpoint, dissociating the copy-number effect of CFHR3 from that of CFHR1 has been difficult, because single gene deletions are extremely rare in humans, and specific mouse knockout models have not yet been developed. The available antibodies against CFHR3 and CFHR1 cross-react with FH and other CFHR peptides, precluding accurate quantification of serum levels of these proteins. Based on limited in vitro functional studies, the effects of CFHR3 and CFHR1 appear to be independent of FH. CFHR1 has been found to inhibit the terminal complement pathway by dampening C5 convertase activity and inhibition of MAC assembly (70). Similar to CFHR1, but unlike FH, CFHR3 also inhibits the C5 convertase. In addition, CFHR3 has been found to act with Factor I to promote degradation of C3b in the absence of FH (71). These actions, however, do not explain the protective effect of lower copy number of CFHR3 and CFHR1. One plausible hypothesis is that CFHR3 and CFHR1 compete with FH for C3b binding but are less effective than FH at accelerating the decay of C3-convertase (71). As a result, the protective effect of FH is enhanced with lower levels of these peptides, but further studies are clearly needed to refine this possibility.

The genetic association at the CFH locus is consistent with prior immunofluoresence studies demonstrating the involvement of the alternative pathway in IgAN: renal tissue staining is typically negative for C1q (classical pathway) and variable for C4d and mannan-binding lectin (lectin pathway) but consistently positive for C3, P, and MAC (5, 72--75). Moreover, circulating levels of activated C3 products are elevated in IgAN (76, 77), and the urinary MAC, FH, and P levels are higher in patients with IgAN than in healthy controls (78). Based on these data, we speculate that the renoprotective effect of CFHR3,1-del may be related to the relatively unopposed inhibitory effect of FH on C3 convertase, overall leading to the suppression of the alternative pathway. These findings open avenues for novel therapeutic approaches for IgAN. For example, targeted depletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1, treatment with recombinant FH, or suppression of the terminal complement pathway with anti-C5 antibodies may be of benefit in IgAN.

The HORMAD2 Locus (Chromosome 22q12)

The fifth GWAS signal was found in a gene-rich area on chromosome 22q12 containing HORMAD2, MTMR3, LIF, OSM, and several other genes. In our study, the association was strongest at rs2412971, an intronic SNP in the HORMAD2 gene, whereas in the Chinese GWAS, the signal peaked at rs12537, which is located in the 3’ untranslated region of the MTMR3 gene. Both of these SNPs are in strong LD (r2 = 0.64, D’ = 0.96) and presumably tag the same causal variant. Among the genes in this locus, both OSM and LIF encode cytokines that have been implicated in mucosal immunity and inflammation. In particular, inactivation of OSM produces thymic atrophy and autoimmune glomerulonephritis in the mouse (79). The functions of other genes within this interval have not been as well characterized. HORMAD2 is part of a HORMA-domain-containing gene family implicated in DNA double-stranded break repair (80), and MTMR3 (encoding myotubularin-related phosphatase 3) is implicated in autophagy (81). Interestingly, the rs2412973 allele (in LD with rs2412971 and rs12537), which is protective against IgAN, has also been associated with increased risk of early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (82).

In our GWAS, protective alleles at this locus were associated with lower serum IgA levels among cases, suggesting that this locus may be involved in the control of IgA production or regulation of mucosal immune response. Moreover, in the larger follow-up study, we observed a genetic interaction of this locus with CFHR3,1-del: the protective effect of rs2412971-A (HORMAD2) allele is reversed among CFHR3,1-del homozygotes. This interaction was most evident in the European cohorts, mainly because of power limitations because the protective alleles at both loci are considerably less frequent in Chinese. The biological basis of this statistical finding remains unknown.

The DEFA Locus (Chromosome 8p23)

The GWAS in the Han Chinese cohort identified a significant signal at rs2738048, centered on the alpha defensin (DEFA) gene cluster. The defensins are microbicidal peptides that are an important component of innate immunity (83, 84). Their positive charge enables electrostatic binding to pathogen cell surfaces, increasing membrane permeability. Defensins also modulate the inflammatory response and have chemoattractant properties. The DEFA gene family is present only in mammals and marsupials. Humans have six DEFA genes: DEFA1--4 are expressed in neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells, and DEFA5 and -6 are expressed in Paneth cells of the gut, supporting their role in mucosal immunity. Notably, a low level of alpha-defensin expression by intestinal Paneth cells is associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease (85).

Similar to CFHR genes, DEFA genes likely arose by segmental duplications during evolution. Owing to high sequence homology in the DEFA gene family, it has been difficult to determine if these genes have similar or unique specialized functions. Studies are further complicated by the significant copy number variation in DEFA1 and DEFA3 genes, which are located in tandem, 4--14 copies per genome (86). High-resolution analysis of this locus is required to determine if the top SNP signal in the IgAN GWAS originates from a specific DEFA gene or is in LD with CNVs at this locus. Nonetheless, these findings provide another connection between inflammatory bowel disease and IgAN, and further implicate mucosal innate immunity in the pathogenesis of these disorders.

The TNFSF13 Locus (Chromosome 17p13)

The IgAN locus containing TNFSF13 and TNFSF12, which encode tumor necrosis factor ligands, was detected in the Han Chinese GWAS. TNFSF13, also known as APRIL (“a proliferation-inducing ligand”),is secreted by dendritic cells, monocytes, activated T cells, or intestinal epithelial cells and is important for T cell--independent generation of IgA-positive B cells, as well as IgA1-to-IgA2 class switching (87, 88). Inactivation of Tnfsf13 in mice produces partial IgA deficiency and reduced IgA antibody responses to mucosal immunization (89). Conversely, overexpression of BAFF (TNFSF13B, a related tumor necrosis factor ligand that has overlapping functions and receptors with APRIL) results in autoimmune disease with commensal flora-dependent deposits of IgA in the renal mesangium (90). Serum levels of APRIL are elevated in many rheumatologic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, and also in patients with IgA nephropathy (90). Inactivating mutations in TNFRSF13B (receptor for both APRIL and BAFF, also known as TACI) produce selective IgA deficiency and common variable immunodeficiency syndrome in humans (91).

Interestingly, the IgAN risk variant in TNFSF13 is associated with increased total IgA levels in IgAN patients (47) but decreased levels in non-IgAN subjects (92). This may be consistent with prior findings that the effects of APRIL on class switching are dependent on the cytokine milieu (93). Although the exact functional consequence of the TNFSF13 risk alleles and its effect on the levels of the IgA1/IgA2 subclasses remain to be determined, these data implicate defects in mucosal immunity and IgA class switching in the pathogenesis of IgAN and suggest an interplay with commensal flora as an important modifier of disease.

GENETIC RISK AND GEOEPIDEMIOLOGY OF IGA NEPHROPATHY

We noted a consistent shift in the cumulative distribution of GWAS risk alleles between major ethnicities: the burden of risk alleles was relatively low in Africans, intermediate for Europeans, and highest for Asians (45). Furthermore, the ethnic differences in allelic frequencies were more pronounced for loci with larger effect sizes, such as HLA-DRB1/DQB1, CHFR3,1-del, and HORMAD2 (Table 1). We therefore formulated a genetic risk score for IgAN (46) based on the number of risk alleles and their corresponding effect size. The most recent refinement of the score also incorporates the nonadditive interaction effect of the CHFR3,1-del and HORMAD2 loci. Accordingly, the ethnic differences in genetic risk were even more striking when the risk score was considered instead of simple allele counts. In aggregate, this risk score explained nearly 5% of disease variance across 12 multiethnic cohorts examined (46). One standard-deviation increase in the score was associated with nearly 50% increase in the risk of disease. This translates into a fivefold increase in risk between individuals from the opposing extremes of the risk score distribution. We have recently implemented an online risk calculator that estimates an individual’s genetic susceptibility in relation to the worldwide average using genotype data. This calculator can be found at the following link: http://www.columbiamedicine.org/divisions/gharavi/resources. Of note, the contribution of the two most recently described loci (DEFA and TNFSF13) has not yet been studied. Their addition in the risk score calculation will likely improve the score’s predictive properties, provided these loci are validated in non-Asian populations.

We also examined the geographic variation in the genetic risk for IgAN across 85 worldwide populations, including individuals sampled by HapMap-III and the Human Genome Diversity Panel as well as our own control datasets. We built a geospatial risk model that confirmed lowest median scores for Africans, intermediate for Middle Easterners and Europeans, and highest for East Asians and Native Americans (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Worldwide geospatial analysis of genetic risk for immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN). Surface interpolation of the standardized risk score over continents reveals increasing genetic risk with increasing distance from Africa. The risk score is derived from seven SNPs representing replicated IgAN susceptibility loci. Symbols represent the locations of 85 sampled populations: the Human Genome Diversity Panel sample (circles), the HapMap-III sample (diamonds), and healthy controls (triangles). Adapted from Reference 46 with permission.

We next examined if variation in genetic risk is also reflected in differences in the prevalence of IgAN. Because the requirement for kidney biopsy diagnosis of IgAN makes determination of population prevalence difficult, we examined the numbers of cases of IgAN reported to the national end-stage renal disease (ESRD) registries. In the analysis of the most recent U.S. Renal Data System dataset, we observed dramatic differences in the prevalence of IgAN-ESRD among the four major U.S. ethnicities (Figure 2). The percentage of ESRD attributable to IgAN was fivefold greater for European-Americans and 15-fold greater for Asian-Americans when compared to African-Americans. Because these individuals represent immigrant populations and the disease prevalence closely reflects the genetic risk of ancestral populations, our data argue against environmental factors as major contributors to disease risk in North America. Interestingly, both the prevalence and genetic risk of Native Americans were considerably higher compared to European-Americans. This is consistent with previous reports of high IgAN occurrence among Native American tribes (94, 95) and comes as no surprise given the genetic relatedness of these populations to their East Asian ancestors.

Figure 2.

Ethnic differences in the prevalence of IgAN in the United States. IgAN-ESRD prevalence by ethnicity is expressed as a proportion of biopsy-diagnosed IgAN in all ESRD (green) and all biopsy-diagnosed primary glomerulonephritis (red). The data were obtained from the USRDS report and reflect disease prevalence as of December 31, 2009. Abbreviations: IgAN, immunoglobulin A nephropathy; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; USRDS, United States Renal Data System.

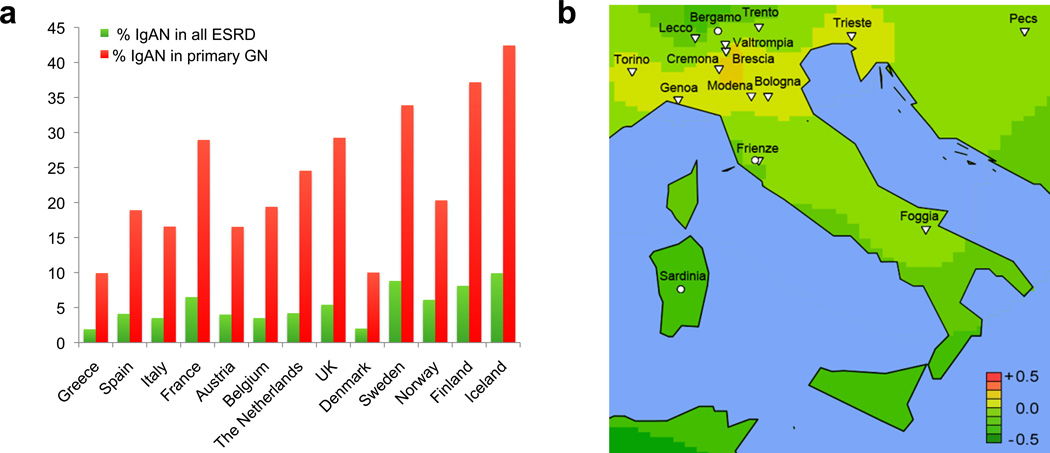

Unexpectedly, higher-resolution geospatial analysis of the European continent revealed an additional south-to-north genetic risk gradient (Figure 3). As predicted by the genetic risk score, analysis of 13 countries reporting to the ERA-EDTA (European Renal Association - European Dialysis and Transplant Association) registry demonstrated the lowest prevalence in the South of Europe (Greece, Italy, Spain) and the highest prevalence in the Northern European countries (Sweden, Finland, Iceland). The analysis of both metrics resulted in concordant results, even after we controlled for potential detection bias due to regional differences in kidney biopsy practices or variability in survival. Findings were robust when we also normalized our data by prevalent counts of ESRD cases, as well as by ESRD due to biopsy-confirmed primary glomerulonephritis. The south-to-north cline in prevalence and genetic risk has not been previously appreciated. Interestingly, higher latitude has previously been associated with increased risk of many other immune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel disease, all of which share common susceptibility loci with IgAN (96--99), suggesting that complex selective pressures, rather than genetic drift alone, have shaped the geospatial distribution of IgAN risk alleles.

Figure 3.

Geoepidemiology of IgAN in Europe. (a) Country-specific IgAN-ESRD prevalence ordered by latitude demonstrates a trend for increased risk in Nordic countries (ERA-EDTA, December 31, 2009). The prevalence of IgAN-ESRD is expressed as a proportion of biopsy-diagnosed IgAN in all ESRD (green) and all biopsy-diagnosed primary glomerulonephritis (red). (b) High-resolution geospatial analysis highlights the area of increased risk in Northern Italy centered over Brescia, Valtrompia, and Cremona. Abbreviations: IgAN, immunoglobulin A nephropathy; ERA-EDTA, European Renal Association - European Dialysis and Transplant Association; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; USRDS, United States Renal Data System.Adapted from Reference 46 with permission.

Finally, we have previously reported high prevalence of primary glomerulonephritis in an isolated population from the Valtrompia valley in Northern Italy. The Alpine villagers in this region have a 3.5-fold higher prevalence of ESRD attributable to primary glomerulonephritis, largely due to IgAN, when compared to the national average (40). Our previous genealogic investigations indicated that the affected individuals have a limited number of ancestors, implying genetic causation and the existence of a founder effect. We included healthy individuals from this region in the geospatial risk analysis of North Italian populations (Figure 3b). Consistent with the prevalence data, the average score in this population was comparable to some of the Northern European countries and ranked first among the 17 Italian populations sampled in our study (46). Thus, we discovered yet another example of covariation of genetic risk score and IgAN prevalence. The high endogamy rates may have maintained risk alleles at high frequency in this region. Unfortunately, the ancestral history of Valtrompia founders is not clear. The founders might have derived from a Northern European gene pool, perhaps during Celtic invasions of Northern Italy around 500--600 BCE, or from Asian ancestry, possibly during Mongol campaigns of the twelfth century. A genome-wide SNP analysis of this isolate may help to better define its ancestral origin.

A NEW PATHOGENESIS MODEL

By combining genetic and biochemical data, we have proposed a model of IgAN pathogenesis that describes sequential hits in innate and adaptive immunity (Figure 4). Our data indicate that IgAN results from a primary, inherited defect in IgA1-producing cells that leads to preferential production of Gd-IgA1. Gd-IgA1 production is likely influenced by variants in cytokine genes such as LIF, OSM (22q12) or TNFSF13 (17p23) that influence IgA1 production and class switching. This glycosylation defect alone is usually benign, as evidenced by the finding that over a quarter of first-degree relatives have elevated Gd-IgA1 levels but no disease. However, in conjunction with inheritance of permissive MHC haplotypes (the strongest signals in GWAS), this genetically elevated Gd-IgA1 elicits production of antiglycan autoantibodies, leading to formation of immune complexes that deposit in the kidney. The pathogenicity of antiglycan antibodies may be enhanced by the presence of specific CDR3 sequences in the heavy-chain antigen-binding domains that enhance binding to Gd-IgA1 (36). Dysregulated mucosal immune response, influenced by variants in TNFSF13 and DEFA loci, and perhaps also affected by the toll-like receptor system (100), may further enhance inflammatory signals, increasing Gd-IgA1 and/or antiglycan antibody production. Tissue injury is modulated by the alternative complement pathway, with variants in the CFHR1 and/or CFHR3 genes, modifying the risk of renal inflammation locally. This model undoubtedly simplifies the pathogenesis of disease, but it provides a rational start for hypothesis testing.

Figure 4.

New pathogenesis model for immunoglobulin A nephropathy based on findings from genetic and biochemical studies.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Genetic studies of IgAN have provided a glimpse into pathogenesis and identified molecular candidates for disease. Nonetheless, the risk loci discovered to date explain only a small fraction of genetic risk, suggesting there are additional genetic and environmental risk factors. Fine mapping or resequencing of risk loci can identify culprit genes and potentially reveal additional independent risk alleles that can explain a larger proportion of disease variance. Additional genome-wide studies, using the GWAS approach in sporadic cases or exome sequencing in multiplex families, are expected to identify additional molecular pathways that can refine the model presented above and reveal common pathogenetic links between IgAN and other immunologic disorders. In particular, discovery of rare mutations with large effect will be valuable, because such variants readily demonstrate the consequences of severe gain or loss of function for organismal physiology and can inform about the therapeutic potential of gene products. Finally, analysis of immunologic and clinical profiles in patients with differing genotypes may also provide clues to selection forces and environmental factors that have driven major differences in risk allele frequency among world populations and shaped the epidemiology of disease.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Berger J, Hinglais N. Les dépôts intercapillaires d’IgA-IgG. J. Urol. Nephrol. (Paris) 1968;74:694–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mestecky J, Raska M, Julian B, et al. IgA nephropathy: molecular mechanisms of the disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2013;8 doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130216. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donadio JV, Grande JP. IgA nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:738–748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennette JC. The immunohistology of IgA nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1988;12:348–352. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(88)80022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomino Y, Endoh M, Nomoto Y, et al. Activation of complement by renal tissues from patients with IgA nephropathy. J. Clin. Pathol. 1981;34:35–40. doi: 10.1136/jcp.34.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emancipator SN. IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein syndrome. In: Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG, editors. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 479–539. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie J, Kiryluk K, Wang W, et al. Predicting progression of IgA nephropathy: new clinical progression risk score. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto M, Wakai K, Kawamura T, et al. A scoring system to predict renal outcome in IgA nephropathy: a nationwide 10-year prospective cohort study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24:3068–3074. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthoux F, Mohey H, Laurent B, et al. Predicting the risk for dialysis or death in IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;22:752–761. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartosik LP, Lajoie G, Sugar L, et al. Predicting progression in IgA nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2001;38:728–735. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odum J, Peh CA, Clarkson AR, et al. Recurrent mesangial IgA nephritis following renal transplantation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1994;9:309–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva FG, Chander P, Pirani CL, et al. Disappearance of glomerular mesangial IgA deposits after renal allograft transplantation. Transplantation. 1982;33:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mestecky J, Tomana M, Crowley-Nowick PA, et al. Defective galactosylation and clearance of IgA1 molecules as a possible etiopathogenic factor in IgA nephropathy. Contrib. Nephrol. 1993;104:172–182. doi: 10.1159/000422410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen AC, Harper SJ, Feehally J. Galactosylation of N- and O-linked carbohydrate moieties of IgA1 and IgG in IgA nephropathy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1995;100:470–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mestecky J, Moro I, Kerr MA, et al. Mucosal immunoglobulins. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, et al., editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3rd. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic; 2005. pp. 153–181. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baenziger J, Kornfeld S. Structure of the carbohydrate units of IgA1 immunoglobulin II. Structure of the O-glycosidically linked oligosaccharide units. J. Biol. Chem. 1974;249:7270–7281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field MC, Dwek RA, Edge CJ, et al. O-linked oligosaccharides from human serum immunoglobulin A1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1989;17:1034–1035. doi: 10.1042/bst0171034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarelli E, Smith AC, Hendry BM, et al. Human serum IgA1 is substituted with up to six O-glycans as shown by matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Carbohydr. Res. 2004;339:2329–2335. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renfrow MB, Cooper HJ, Tomana M, et al. Determination of aberrant O-glycosylation in the IgA1 hinge region by electron capture dissociation Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19136–19145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomana M, Matousovic K, Julian BA, et al. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in sera of IgA nephropathy patients is present in complexes with IgG. Kidney Int. 1997;52:509–516. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomana M, Novak J, Julian BA, et al. Circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy consist of IgA1 with galactose-deficient hinge region and antiglycan antibodies. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen AC, Bailey EM, Brenchley PEC, et al. Mesangial IgA1 in IgA nephropathy exhibits aberrant O-glycosylation: observations in three patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60:969–973. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060003969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiki Y, Odani H, Takahashi M, et al. Mass spectrometry proves under-O-glycosylation of glomerular IgA1 in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1077–1085. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590031077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AC, de Wolff JF, Molyneux K, et al. O-Glycosylation of serum IgD in IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:1192–1199. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Helm-van Mil AHM, Smith AC, Pouria S, et al. Immunoglobulin A multiple myeloma presenting with Henoch-Schönlein purpura associated with reduced sialylation of IgA1. Br. J. Haematol. 2003;122:915–917. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zickerman AM, Allen AC, Talwar V, et al. IgA myeloma presenting as Henoch-Schönlein purpura with nephritis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2000;36:E19. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.16221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki H, Moldoveanu Z, Hall S, et al. IgA1-secreting cell lines from patients with IgA nephropathy produce aberrantly glycosylated IgA1. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:629–639. doi: 10.1172/JCI33189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moldoveanu Z, Wyatt RJ, Lee J, et al. Patients with IgA nephropathy have increased serum galactose-deficient IgA1 levels. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hastings MC, Moldoveanu Z, Julian BA, et al. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in African Americans with IgA nephropathy: serum levels and heritability. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;5:2069–2074. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03270410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin X, Ding J, Zhu L, et al. Aberrant galactosylation of IgA1 is involved in the genetic susceptibility of Chinese patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24:3372–3375. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao N, Hou P, Lv J, et al. The level of galactose-deficient IgA1 in the sera of patients with IgA nephropathy is associated with disease progression. Kidney Int. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.197. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scivittaro V, Ranieri E, Di Cillo M, et al. In vitro immunoglobulin production in relatives of patients with IgA nephropathy. Clin. Nephrol. 1994;42:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scivittaro V, Gesualdo L, Ranieri E, et al. Profiles of immunoregulatory cytokine production in vitro in patients with IgA nephropathy and their kindred. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994;96:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gharavi AG, Moldoveanu Z, Wyatt RJ, et al. Aberrant IgA1 glycosylation is inherited in familial and sporadic IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:1008–1014. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007091052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiryluk K, Moldoveanu Z, Sanders JT, et al. Aberrant glycosylation of IgA1 is inherited in both pediatric IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis. Kidney Int. 2011;80:79–87. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki H, Fan R, Zhang Z, et al. Aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 in IgA nephropathy patients is recognized by IgG antibodies with restricted heterogeneity. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1668–1677. doi: 10.1172/JCI38468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldo FB. Systemic immune response after mucosal immunization in patients with IgA nephropathy. J. Clin. Immunol. 1992;12:21–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00918269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Julian BA, Quiggins PA, Thompson JS, et al. Familial IgA nephropathy. Evidence of an inherited mechanism of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985;312:202–208. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501243120403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scolari F, Amoroso A, Savoldi S, et al. Familial occurrence of primary glomerulonephritis: evidence for a role of genetic factors. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1992;7:587–596. doi: 10.1093/ndt/7.7.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izzi C, Sanna-Cherchi S, Prati E, et al. Familial aggregation of primary glomerulonephritis in an Italian population isolate: Valtrompia study. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1033–1040. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connell PJ, Ibels LS, Thomas MA, et al. Familial IgA nephropathy: a study of renal disease in an Australian aboriginal family. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1987;17:27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1987.tb05045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gharavi AG, Yan Y, Scolari F, et al. IgA nephropathy, the most common cause of glomerulonephritis, is linked to 6q22-23. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:354–357. doi: 10.1038/81677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bisceglia L, Cerullo G, Forabosco P, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in Italian families with IgA nephropathy: suggestive linkage for two novel IgA nephropathy loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:1130–1134. doi: 10.1086/510135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feehally J, Farrall M, Boland A, et al. HLA has strongest association with IgA nephropathy in genome-wide analysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:1791–1797. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gharavi AG, Kiryluk K, Choi M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for IgA nephropathy. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:321–327. doi: 10.1038/ng.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiryluk K, Li Y, Sanna-Cherchi S, et al. Geographic differences in genetic susceptibility to IgA nephropathy: GWAS replication study and geospatial risk analysis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu XQ, Li M, Zhang H, et al. A genome-wide association study in Han Chinese identifies multiple susceptibility loci for IgA nephropathy. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:178–182. doi: 10.1038/ng.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore RH, Hitman GA, Medcraft J, et al. HLA-DP region gene polymorphism in primary IgA nephropathy: no association. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1992;7:200–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a092105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raguenes O, Mercier B, Cledes J, et al. HLA class II typing and idiopathic IgA nephropathy (IgAN): DQB1*0301, a possible marker of unfavorable outcome. Tissue Antigens. 1995;45:246–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1995.tb02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fennessy M, Hitman GA, Moore RH, et al. HLA-DQ gene polymorphism in primary IgA nephropathy in three European populations. Kidney Int. 1996;49:477–480. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:827–829. doi: 10.1038/ng2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rioux JD, Goyette P, Vyse TJ, et al. Mapping of multiple susceptibility variants within the MHC region for 7 immune-mediated diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18680–18685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909307106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kugathasan S, Baldassano RN, Bradfield JP, et al. Loci on 20q13 and 21q22 are associated with pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1211–1215. doi: 10.1038/ng.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oksenberg JR, Baranzini SE, Sawcer S, Hauser SL. The genetics of multiple sclerosis: SNPs to pathways to pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:516–526. doi: 10.1038/nrg2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barcellos LF, May SL, Ramsay PP, et al. High-density SNP screening of the major histocompatibility complex in systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrates strong evidence for independent susceptibility regions. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mignot E, Lin L, Rogers W, et al. Complex HLA-DR and -DQ interactions confer risk of narcolepsy-cataplexy in three ethnic groups. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:686–699. doi: 10.1086/318799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singer JB, Lewitzky S, Leroy E, et al. A genome-wide study identifies HLA alleles associated with lumiracoxib-related liver injury. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:711–714. doi: 10.1038/ng.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Erlich H, Valdes AM, Noble J, et al. HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes. 2008;57:1084–1092. doi: 10.2337/db07-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coppo R, Camilla R, Alfarano A, et al. Upregulation of the immunoproteasome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;75:536–541. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou X, Lee JE, Arnett FC, et al. HLA-DPB1 and DPB2 are genetic loci for systemic sclerosis: a genome-wide association study in Koreans with replication in North Americans. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3807–3814. doi: 10.1002/art.24982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skerka C, Zipfel PF. Complement factor H related proteins in immune diseases. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl. 8):I9–I14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boon CJ, van de Kar NC, Klevering BJ, et al. The spectrum of phenotypes caused by variants in the CFH gene. Mol. Immunol. 2009;46:1573–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis--a new look at an old entity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1108178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, et al. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hughes AE, Orr N, Esfandiary H, et al. A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1173–1177. doi: 10.1038/ng1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raychaudhuri S, Ripke S, Li M, et al. Associations of CFHR1-CFHR3 deletion and a CFH SNP to age-related macular degeneration are not independent. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:553–555. doi: 10.1038/ng0710-553. author reply 55–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malik TH, Lavin PJ, Goicoechea de Jorge E, et al. A hybrid CFHR3-1 gene causes familial C3 glomerulopathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012;23:1155–1160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jozsi M, Licht C, Strobel S, et al. Factor H autoantibodies in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome correlate with CFHR1CFHR3 deficiency. Blood. 2008;111:1512–1514. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-109876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Strobel S, Abarrategui-Garrido C, Fariza-Requejo E, et al. Factor H-related protein 1 neutralizes anti-factor H autoantibodies in autoimmune hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2011;80:397–404. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heinen S, Hartmann A, Lauer N, et al. Factor H-related protein 1 (CFHR-1) inhibits complement C5 convertase activity and terminal complex formation. Blood. 2009;114:2439–2447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fritsche LG, Lauer N, Hartmann A, et al. An imbalance of human complement regulatory proteins CFHR1, CFHR3 and factor H influences risk for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4694–4704. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wyatt RJ, Julian BA. Activation of complement in IgA nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1988;12:437–442. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(88)80042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miyamoto H, Yoshioka K, Takemura T, et al. Immunohistochemical study of the membrane attack complex of complement in IgA nephropathy. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1988;413:77–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00844284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lhotta K, Wurzner R, Konig P. Glomerular deposition of mannose-binding lectin in human glomerulonephritis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1999;14:881–886. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Espinosa M, Ortega R, Gomez-Carrasco JM, et al. Mesangial C4d deposition: a new prognostic factor in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24:886–891. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zwirner J, Burg M, Schulze M, et al. Activated complement C3: a potentially novel predictor of progressive IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1257–1264. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wyatt RJ, Kanayama Y, Julian BA, et al. Complement activation in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1987;31:1019–1023. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Onda K, Ohsawa I, Ohi H, et al. Excretion of complement proteins and its activation marker C5b-9 in IgA nephropathy in relation to renal function. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Esashi E, Ito H, Minehata K, et al. Oncostatin M deficiency leads to thymic hypoplasia, accumulation of apoptotic thymocytes and glomerulonephritis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:1664–1670. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wojtasz L, Daniel K, Roig I, et al. Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taguchi-Atarashi N, Hamasaki M, Matsunaga K, et al. Modulation of local PtdIns3P levels by the PI phosphatase MTMR3 regulates constitutive autophagy. Traffic. 2010;11:468–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Imielinski M, Baldassano RN, Griffiths A, et al. Common variants at five new loci associated with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1335–1340. doi: 10.1038/ng.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hazlett L, Wu M. Defensins in innate immunity. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lehrer RI, Lu W. alpha-Defensins in human innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2012;245:84–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wehkamp J, Salzman NH, Porter E, et al. Reduced Paneth cell alpha-defensins in ileal Crohn’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18129–18134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505256102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aldred PM, Hollox EJ, Armour JA. Copy number polymorphism and expression level variation of the human alpha-defensin genes DEFA1 and DEFA3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:2045–2052. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stein JV, Lopez-Fraga M, Elustondo FA, et al. APRIL modulates B and T cell immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1587–1598. doi: 10.1172/JCI15034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.He B, Xu W, Santini PA, et al. Intestinal bacteria trigger T cell-independent immunoglobulin A(2) class switching by inducing epithelial-cell secretion of the cytokine APRIL. Immunity. 2007;26:812–826. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Castigli E, Scott S, Dedeoglu F, et al. Impaired IgA class switching in APRIL-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307348101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McCarthy DD, Kujawa J, Wilson C, et al. Mice overexpressing BAFF develop a commensal flora-dependent, IgA-associated nephropathy. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:3991–4002. doi: 10.1172/JCI45563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Castigli E, Geha RS. Molecular basis of common variable immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006;117:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.038. quiz 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Osman W, Okada Y, Kamatani Y, et al. Association of common variants in TNFRSF13B, TNFSF13, and ANXA3 with serum levels of non-albumin protein and immunoglobulin isotypes in Japanese. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD, Johansen FE, Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal. Immunol. 2008;1:11–22. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hughson MD, Megill DM, Smith SM, et al. Mesangiopathic glomerulonephritis in Zuni (New Mexico) Indians. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1989;113:148–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith SM, Tung KS. Incidence of IgA-related nephritides in American Indians in New Mexico. Hum. Pathol. 1985;16:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shapira Y, Agmon-Levin N, Shoenfeld Y. Defining and analyzing geoepidemiology and human autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2010;34:J168–J177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Borchers AT, Uibo R, Gershwin ME. The geoepidemiology of type 1 diabetes. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010;9:A355–A365. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Milo R, Kahana E. Multiple sclerosis: geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010;9:A387–A394. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Handel AE, Handunnetthi L, Giovannoni G, et al. Genetic and environmental factors and the distribution of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010;17:1210–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Suzuki H, Suzuki Y, Narita I, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 affects severity of IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:2384–2395. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]