Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effect of initiating antidepressant therapy with a generic prescription on adherence to antidepressant therapy among Medicare patients. A second objective is to assess how the effect might be moderated by the Medicare Part D coverage gap.

Research Design

Adherence to antidepressant therapy was measured by (a lack of) disruption in medication use defined by a gap of >=30 days in antidepressant possession and monthly days of possession, both measured over 180 days since antidepressant initiation. We used a 5% random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who received a new depression diagnosis in the first half of 2007 and initiated antidepressant therapy within 60 days (n=16,778). We estimated a Cox proportional hazard model for antidepressant disruption and a mixed-effects linear model for monthly possession. All analyses were stratified by four cohorts defined by Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) status and Medicare entitlement (aged vs. disabled).

Results

Generic initiation was associated with improved adherence among all four cohorts, with a stronger effect among the non-LIS patients. Hazard ratios for antidepressant disruption ranged from 0.71 (95% CI: 0.53 to 0.96) among the non-LIS, disabled to 0.88 (95% CI: [0.79, 0.98]) among the LIS, aged. Generic initiation was associated with increases in days of monthly possession in all four cohorts and an additional benefit during the coverage gap for non-LIS patients.

Conclusions

Generic initiation can be an important tool to improve adherence to antidepressant treatment among Medicare patients and to mitigate the negative effects of the Part D coverage gap.

Keywords: generic initiation, antidepressants, adherence, Medicare Part D

Antidepressants are among the most prescribed drugs for U.S. adults.1 Among people 65 years or older, 14 percent use antidepressants annually for depression, anxiety, or another indication.2 While adherence to antidepressants is critical to realizing the effectiveness of antidepressant treatment,3, 4 around 40% of Medicare managed care patients discontinue their antidepressant treatment prematurely. 5 High out-of-pocket costs due to lack of drug coverage or high cost-sharing has been shown to decrease drug adherence in most populations,6 including Medicare beneficiaries using antidepressant medication.7

Generic antidepressants are now widely available.8 By 2007, most major brands of second-generation antidepressants had generic equivalents in the U.S. market. Generic use has the potential to improve adherence to antidepressant therapy because patient out-of-pocket costs for generics are nearly always much lower than for brands.9 For example, for patients receiving Medicare prescription benefits in 2011, the median co-payment was $7 for generics, $42 for preferred brands, and $78 for non-preferred brands.10 Choice of generic or brand name is partly a function of provider preferences.11 When a branded drug is prescribed and in absence of a “Dispense as Written” request by the prescriber or the patient, patients often receive a generic equivalent because of state mandates of generic substitution12 or pharmacist discretion. The generic (vs. branded) status of the first prescription is likely highly influential in determining generic or branded drug use throughout the course of treatment and therefore may have important implications for patient adherence to chronic medication therapy.

The cost advantage of generics has greater implications under Medicare’s current prescription drug benefit (Part D) than under a traditional insurance plan because of the Part D coverage gap. For example, in 2007 (the study year), under most plans, patients whose total Part D-covered drug spending reached $2510.00 were responsible for 100% of drug costs until their total spending reached $5726.00, or until the start of 2008. An estimated 3.4 million beneficiaries (about 14% of all Part D enrollees) reached the coverage gap in 2007.13 While the Affordable Care Act will take steps to gradually close the coverage gap over the 10 years starting 2011, in the near term, differences in out-of-pocket costs between branded and generic antidepressants will remain greater during the coverage gap than otherwise.

In this study, we assessed the effects of initiating antidepressant treatment with a generic (vs. branded) prescription (“generic initiation”) on adherence to antidepressant therapy for the treatment of depression. Our study contributes to the literature by examining both the effect of generic initiation by itself and how the effect might be moderated by the presence of the Medicare Part D coverage gap.

Methods

Data

We used data from a 5% random sample of beneficiaries with depression in 2006–2007 from the Medicare Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW).14 Files used in this study included carrier claims and the Part D Prescription Drug Event file. We also used the Beneficiary Summary File and Chronic Condition Summary File to derive demographic and comorbidity information for beneficiaries.

Study Sample

Our study population is Medicare fee-for-service patients who experienced a new episode of depression and subsequently initiated antidepressant therapy within 60 days of the new depression diagnosis. This is a population with a clear clinical indication for depression treatment. To be included in the analysis, all beneficiaries were required to be continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B throughout 2006 and 2007. Because Part D had an enrollment deadline of May 11 in 2006, we further required beneficiaries to be continuously enrolled in Part D from July 1, 2006 to December 31, 2007.

To identify patients experiencing a new episode of depression, we first identified, for each patient, the first physician service claim between January 1 and June 30 of 2007 that had major depression, depressive disorder not elsewhere classified, or dysthymia as a primary or secondary diagnosis (ICD-9 codes: 296.2x, 296.3x, 311x, and 300.4x) (the “index diagnosis”). We further excluded patients who had any physician claim with a depression diagnosis or antidepressant use during the 6 months prior to the index diagnosis. We then restricted the sample to patients who filled an antidepressant prescription within 60 days of the index date. The resulting study sample contained patients who initiated antidepressant therapy no later than July 4 of 2007 to allow for follow-up data covering 180 days after initiation for every patient. We excluded 111 patients who had missing Part D benefit phase information. We also excluded a small number of beneficiaries who were entitled to Medicare because of end-stage renal disease.

More than half of patients in the study sample received the Part D low income subsidy (LIS) and thus were not subject to the coverage gap. Among patients not receiving LIS, we excluded patients who were already in the coverage gap by the time they initiated antidepressant therapy (n=434), since these patients faced very different cost-sharing compared to patients who transitioned into the coverage gap after antidepressant initiation. Among non-LIS patients who transitioned into the coverage gap during the 180 days, about 20% spent through the coverage gap later in 2007 and transitioned to the catastrophic coverage phase in which they had almost complete coverage. A recent study of a depression cohort found that patients who eventually attained catastrophic coverage did not change their medication use while in the coverage gap.15 We thus excluded these patients (n=431) in our main analysis. In a sensitivity analysis, we included both types of patients to examine the robustness of our findings. Our main analytic sample included 16,778 beneficiaries.

We identified four distinct patient cohorts defined by their Medicare entitlement status (aged vs. disabled) and Part D LIS status. Compared to the aged, disabled beneficiaries differ in both socioeconomic status and complexity of health care needs. Patients receiving LIS are either Medicare-Medicaid dual enrollees or have limited income or resources;16 as shown below, they also have more co-morbid conditions. We thus chose not to treat the LIS patients as a “control” cohort for the non-LIS patients (since their baseline trends in medication may not be comparable), but instead stratified all our analysis by the four patient populations.

We used the Multum Lexicon drug classification system17 to identify antidepressants (and whether a given prescription was generic or branded) based on the National Drug Code. We used drug dispensing date and days of supply to determine time intervals during which a patient was in possession of antidepressants. When two or more intervals overlapped, we counted the overlapping period only once.

Main Outcome Measures

We created two measures of antidepressant adherence. The first measure is disruption in antidepressant therapy during the 180 days after initiation, equal to 1 if there was a gap in antidepressant possession of 30 days or longer and 0 otherwise. Patients who switched medication during the 180 days were considered adherent (i.e., no disruption) as long as they did not experience a gap of >=30 days. A follow-up of 180 days was based on depression treatment guidelines that recommend minimum length of pharmacotherapy during acute and continuation phases of treatment.3, 4, 18 The 30-day gap was defined so that patients who retained antidepressants from previous fills or who had a “wash-out” period between medication changes would not be incorrectly classified as non-adherent.19

The second measure, monthly days of antidepressant possession, is defined as the number of days in each of the six months following antidepressant initiation that the patient was in possession of antidepressants. We chose a monthly measure of possession (rather than the typical medication possession ratio over 180 days) because the monthly measure allows us to examine the dynamics of antidepressant use in relationship to the onset of the coverage gap.

Independent Variables

Our primary independent variable is the generic/brand status of the first prescription. Of all the branded initiations in our sample, 83% were one of three antidepressants that did not yet have a generic equivalent on the U.S. market in 2007: Lexapro (generic name: escitalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or SSRI; accounting for 44% of all branded initiations), Cymbalta (duloxetine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or SNRI; 20%) and Effexor XR (venlafaxine XR, an SNRI; 19%). While our main analysis included all classes of antidepressants, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by including only patients who initiated their treatment with a generic or branded SSRI.

For non-LIS patients, whose Part D coverage includes a coverage gap, a second independent variable of interest was an indicator of whether the patient was in the coverage gap at a given time. In analyses of both outcomes, this indicator is time-varying since patients may transition into the coverage gap during the follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

For disruption in antidepressant therapy, we estimated a Cox proportional hazard model of time to disruption. For non-LIS patients, in addition to generic initiation, independent variables included Part D benefit phase (coverage gap vs. pre-coverage gap) and an interaction between generic initiation and coverage gap. This allowed us to examine if the effect of generic initiation was stronger as patients experienced the coverage gap. We conducted tests of the proportional hazard assumption based on Schoenfeld residuals.20

For monthly days with antidepressant possession, we estimated a mixed-effects linear model using data at the patient-month level, with a patient-level random intercept to account for correlations between multiple observations clustered within a given patient. Generic initiation was the primary independent variable. The models estimated among the non-LIS cohorts also included dichotomous indicators of number of complete months that a patient had been in the coverage gap, which ranged from 1 to 5. This was to allow the effect of coverage gap to differ with the length of time spent in the coverage gap. Interaction terms between generic initiation and each of the coverage gap month indicators were also included. To control for time patterns in antidepressant use that are independent from the effects of generic initiation and experience of the coverage gap, we included ordinal indicators of months following antidepressant initiation.

In all analyses, we controlled for patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), measures of patient disease burden (indicators of 9 comorbid chronic condition categories based on CCW definition21 and the natural log of total prescription drug spending in 2007), and the specialty of the clinician associated with the index clinical encounter that established the new depression diagnosis (primary care, mental health specialty, or other medical specialty).

Results

Of the 16,778 patients in our study sample, 65% received LIS in 2007 compared with a national average of 36%,16 reflecting the substantially lower socioeconomic status of patients with depression (Table 1). Close to 50% of LIS patients were entitled to Medicare because of disability rather than old age compared to 11% among the non-LIS sample. The LIS sample was less likely to be white and had a greater number of co-morbid conditions. Total prescription drug costs in 2007 for the two cohorts receiving LIS were 2–3 times higher than the non-LIS cohorts of the same entitlement status. Patients receiving LIS were also more likely to have received their depression diagnosis from a mental health specialist, and less likely to have received it from a primary care clinician. Of the non-LIS, 30% of the aged transitioned into the coverage gap during the 180-day follow-up compared to 25% of the disabled.

Table 1.

Descriptive sample statistics

| LIS | Non-LIS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged (n=5,679) | Disabled (n=5,210) | Aged (n=5,243) | Disabled (n=646) | |

| Age – y (± S.D.) | 78.9 (±8.3) | 49.0 (±9.9) | 77.9 (±7.6) | 53.6 (8.5) |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 4716 (83.0) | 3393 (65.1) | 4250 (81.1) | 400 (61.9) |

| Race/ethnicity – no. (%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 4668 (82.4) | 4195 (80.7) | 5080 (97.0) | 569 (88.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 560 (9.9) | 679 (13.1) | 83 (1.6) | 45 (7.0) |

| Hispanic | 272 (4.8) | 177 (3.4) | 32 (0.6) | 10 (1.6) |

| Other race/ethnicity | 166 (2.9) | 147 (2.8) | 43 (0.8) | 22 (3.4) |

| # of co-morbid conditions† (± S.D.) | 2.9 (±1.5) | 1.3 (±1.3) | 2.1 (±1.4) | 1.0 (±1.2) |

| Total Rx costs in 2007 – $ (± S.D.) | 5330.3 (±4095.8) | 7101.3 (±7476.2) | 2674.8 (±2591.9) | 2716.0 (±4221.0) |

| Diagnosing clinician – no. (%) | ||||

| Primary care | 3732 (65.7) | 2894 (55.6) | 3930 (75.0) | 387 (59.9) |

| Mental health specialty | 1457 (25.7) | 1506 (28.9) | 819 (15.6) | 179 (27.7) |

| Other specialty | 490 (8.6) | 810 (15.6) | 494 (9.4) | 80 (12.4) |

| Generic (vs. branded) initiation# – no. (%) | 3862 (68.0) | 3225 (61.9) | 3581 (68.3) | 425 (65.8) |

| Experienced coverage gap during 180 days – no. (%) | - | - | 1567 (29.9) | 164 (25.4) |

| Disruption in antidepressant therapy over 180 days‡ – % (95% CI) | 29.3 [28.1, 30.4] | 31.4 [30.2, 32.7] | 35.2 [33.8, 36.5] | 39.3 [35.6, 43.1] |

| Monthly possession of antidepressants – days (95% CI) | ||||

| 1st month | 29.7 [29.6, 29.7] | 29.7 [29.7, 29.8] | 29.7 [29.7, 29.8] | 29.8 [29.7, 29.9] |

| 2nd month | 23.9 [23.6, 24.2] | 22.7 [22.4, 23.0] | 22.5 [22.2, 22.8] | 21.5 [20.6, 22.4] |

| 3rd month | 23.5 [23.3, 23.8] | 23.0 [22.7, 23.3] | 22.6 [22.3, 22.9] | 22.0 [21.1, 22.9] |

| 4th month | 22.8 [22.6, 23.1] | 22.4 [22.0, 22.7] | 21.3 [21.0, 21.7] | 20.1 [19.2, 21.0] |

| 5th month | 22.7 [22.5, 23.0] | 22.2 [21.9, 22.5] | 21.2 [20.9, 21.5] | 20.0 [19.0, 20.9] |

| 6th month | 22.6 [22.3, 22.9] | 21.8 [21.5, 22.1] | 20.8 [20.5, 21.2] | 19.0 [18.1, 20.0] |

LIS – Low Income Subsidy; S.D. – standard deviation; CI - confidence interval

# of co-morbid conditions is a count of the presence of the following conditions: Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular conditions (atrial fibrillation, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, stroke/transient ischemic attack), chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, eye conditions (cataract or glaucoma), hip fracture, osteoporosis/rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis, and cancer (breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, endometrial cancer). All conditions were defined based on Chronic Condition Warehouse rules based on ICD-9 diagnostic codes in Medicare claims.

Generic initiation is 1 (0 otherwise) if the prescription filled at the initiation of the therapy was a generic (vs. branded) antidepressant.

Disruption in antidepressant therapy was defined as a gap of 30 days or longer in the possession of antidepressants.

The rate of generic initiation ranged from 62% to 68% across the four patient cohorts. Of all patients with generic initiation, 11.6% switched to a branded antidepressant within 180 days, while 30.6% of patients with branded initiation switched to generics, indicating strong persistence of generic (or branded) choice throughout treatment episode and significance of the initial drug choice. Mean out-of-pocket cost for a 30-day supply of antidepressants was substantially lower for generic vs. branded initiations: for the LIS, it was $1.00 if generic compared to $3.71 if branded; for the non-LIS, it was $6.78 if generic compared to $35.78 if branded.

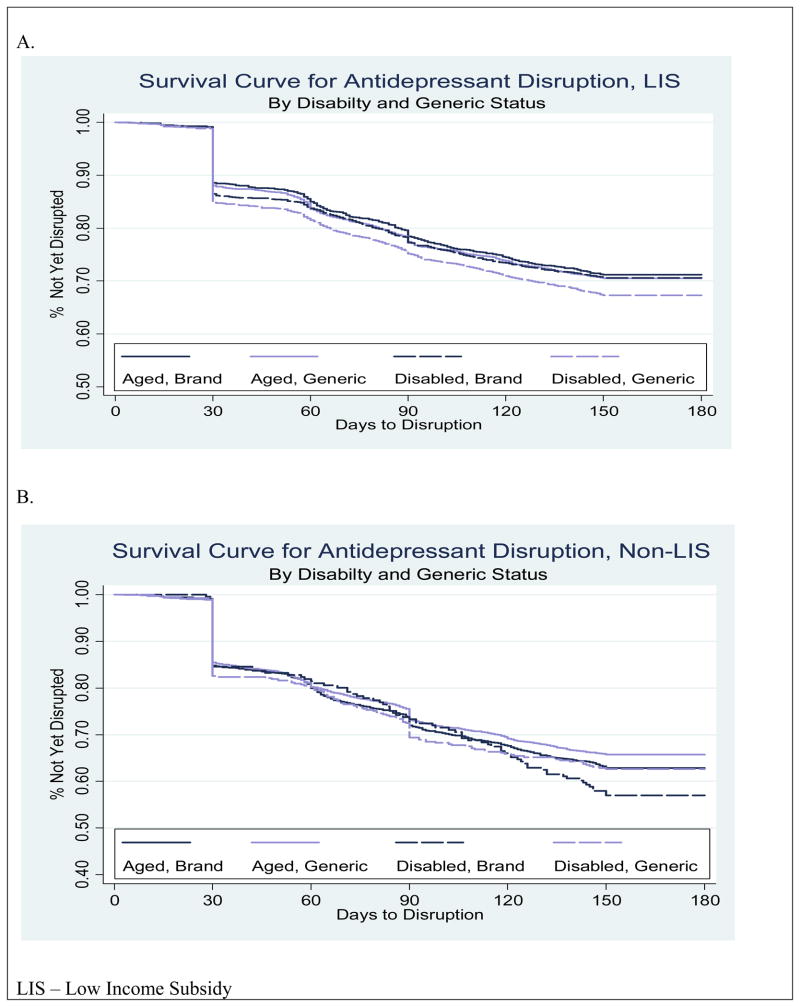

Antidepressant Disruption

Rate of disruption in antidepressant therapy ranged from 29.3% (95% CI: 28.1–30.4%) among the LIS, aged to 39.3% (95% CI: 35.6–43.1%) among the non-LIS, disabled (Table 1). Figures 1A and 1B show (unadjusted) Kaplan-Meier survival curves by patient disability status and generic status of first antidepressant for LIS and non-LIS patients, respectively. Both figures show a sharp increase in disruption (decline in the survival curves) at 30 days after antidepressant initiation. Among the LIS (Figure 1A), a greater proportion of disabled patients with generic initiation disrupted at 30 days; their survival curve was below those of the other three groups for the rest of the follow-up. Among the non-LIS (Figure 1B), survival curves for all four groups traced each other closely until around the 120th day when disabled patients with branded initiation started to experience a greater risk of disruption.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for disruption in antidepressant therapy by disability status and generic status of first antidepressant.

LIS – Low Income Subsidy

Tests of the proportional hazard assumption indicated no evidence of violation of the assumption in any of the Cox models we estimated. Results (Table 2) show that generic initiation was associated with a lower hazard of treatment disruption across all four cohorts. Among LIS patients, the Hazard Ratio (HR) for generic initiation was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.79–0.98, p=0.020) for the aged and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.75–0.93, p=0.001) for the disabled. For the non-LIS patients, HRs for generic initiation were lower: 0.78 (95% CI: 0.70–0.87, p<0.001) among the aged and 0.71 (95% CI: 0.53–0.96, p=0.025) among the disabled. The HR associated with the coverage gap was 2.05 (95% CI: 1.18–3.55, p=0.010) among the non-LIS, disabled. The HRs for the interaction between generic initiation and the coverage gap were below one in both analyses but not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Disruption in antidepressant therapy

| Hazard Ratio [95% CI] (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIS | Non-LIS | |||

| Aged | Disabled | Aged | Disabled | |

| Generic initiation | 0.88 [0.79, 0.98] (p=0.020) | 0.84 [0.75, 0.93] (p=0.001) | 0.78 [0.70, 0.87] (p<0.001) | 0.71 [0.53, 0.96] (p=0.025) |

| Coverage gap (vs. pre-coverage gap) | 1.27 [0.98, 1.65] (p=0.075) | 2.05 [1.18, 3.55] (p=0.010) | ||

| Generic initiation * coverage gap | 0.92 [0.65, 1.30] (p=0.621) | 0.70 [0.27, 0.79] (p=0.455) | ||

LIS – Low Income Subsidy; S.D. – standard deviation; CI - confidence interval

Results are based on Cox proportional hazard models that controlled for patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), measures of patient disease burden (indicators of 9 co-morbid conditions based on Chronic Condition Warehouse definition and the natural log of total prescription drug spending in 2007), and the specialty of the diagnosing clinician associated with the index outpatient visit (primary care, mental health specialty, or other medical specialty).

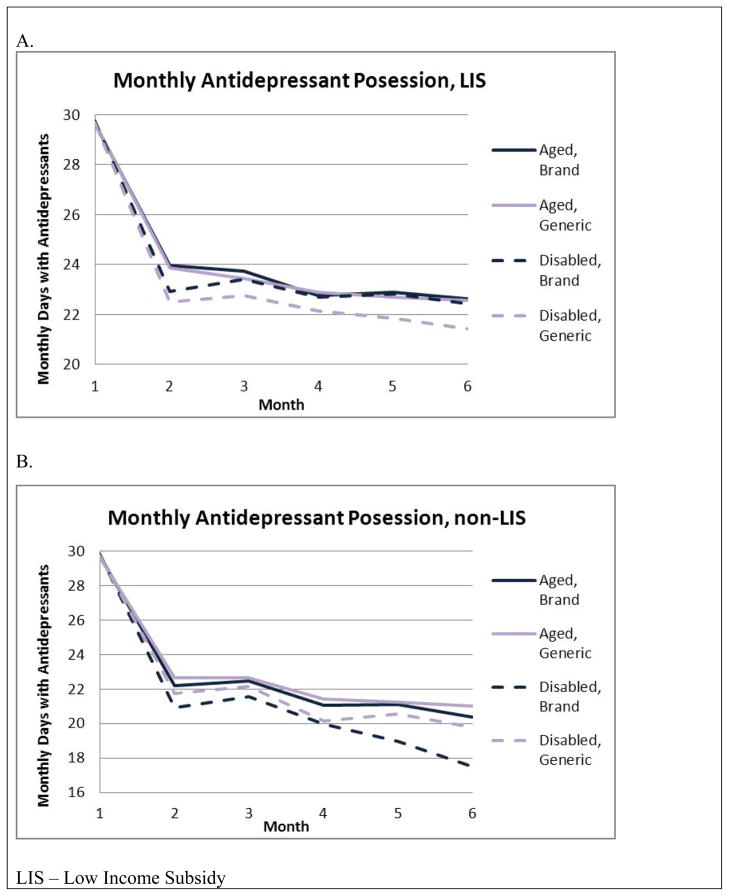

Monthly Antidepressant Possession

As depicted in Figures 2A and 2B, all four cohorts experienced sharp declines in monthly possession from the first to second month. The non-LIS, disabled patients with a branded initiation began to experience a sharper decline in possession in the 4th month, leading to 2–4 fewer days of possession in Month 6 compared with the other three cohorts (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Monthly days of antidepressant possession, by disability status and generic status of first antidepressant

LIS – Low Income Subsidy

Based on the mixed-effects models (Table 3), generic initiation was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in monthly possession in all four cohorts: 0.6 days (95% CI: 0.2–1.0, p=0.003) for the LIS, aged and 0.7 days (95% CI: 0.3–1.1, p<0.001) for the LIS, disabled; 0.9 days (95% CI: 0.5–1.4, p<0.001) for the non-LIS, aged and 2.1 days (95% CI: 0.7–3.4, p<0.001) for the non-LIS, disabled. For the non-LIS, aged, experiencing the coverage gap was not significantly associated with reductions in monthly possession except for the 3rd month in the coverage gap (1.1 fewer days, 95% CI: −2.2–0.0, p=0.045). For the disabled, however, the coverage gap had a significant effect while patients were experiencing the 2nd (−4.1 days, 95% CI: −6.6 to −1.7, p=0.001) and 3rd complete month (−4.1 days, 95% CI: −7.2 to −1.0, p=0.001) in the coverage gap. Generic initiation was associated with an additional increase in monthly possession among non-LIS patients experiencing the coverage gap. For example, for disabled patients, generic initiation was associated with an additional 4.1 days (95% CI: 0.4 to 7.8, p=0.032) of possession when patients were experiencing the 2nd month in the coverage gap.

Table 3.

Monthly days of antidepressant possession

| Incremental Days [95% CI] (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIS | Non-LIS | |||

| Aged | Disabled | Aged | Disabled | |

| Generic initiation | 0.6 [0.2, 1.0] (p=0.003) | 0.7 [0.3, 1.1] (p<0.001) | 0.9 [0.5, 1.4] (p<0.001) | 2.1 [0.7, 3.4] (p=0.002) |

| 1st month in coverage gap | 0.1 [−0.7, 0.8] (p=0.885) | −0.6 [−2.7, 1.5] (p=0.584) | ||

| 2nd month in coverage gap | 0.1 [−0.8, 0.9] (p=0.896) | −4.1 [−6.6, −1.7] (p=0.001) | ||

| 3rd month in coverage gap | −1.1 [−2.2, 0.0] (p=0.045) | −4.1 [−7.2, −1.0] (p=0.009) | ||

| 4th month in coverage gap | −1.2 [−2.8, 0.3] (p=0.116) | −3.8 [−7.7, 0.2] (p=0.062) | ||

| 5th month in coverage gap | −0.4 [−2.8, 2.0] (p=0.749) | 0.7 [−4.6, 6.0] (p=0.792) | ||

| Generic initiation * 1st month in coverage gap | 1.0 [0.0, 2.0] (p=0.047) | −1.9 [−5.0, 1.2] (p=0.224) | ||

| Generic initiation * 2nd month in coverage gap | 0.8 [−0.4, 1.9] (p=0.177) | 4.1 [0.4, 7.8] (p=0.032) | ||

| Generic initiation * 3rd month in coverage gap | 1.4 [0.0, 2.8] (p=0.047) | 4.4 [−0.2, 9.1] (p=0.063) | ||

| Generic initiation * 4th month in coverage gap | 2.4 [0.4, 4.3] (p=0.017) | 2.9 [−3.0, 8.9] (p=0.333) | ||

| Generic initiation * 5th month in coverage gap | 0.3 [−2.9, 3.6] (p=0.847) | 1.8 [−6.5, 10.1] (p=0.676) | ||

LIS – Low Income Subsidy; S.D. – standard deviation; CI - confidence interval

Results are based on mixed-effects linear models at the patient-month level, with a patient-level random intercept. All models controlled for patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity), measures of patient disease burden (indicators of 9 co-morbid conditions based on Chronic Condition Warehouse definition and the natural log of total prescription drug spending in 2007), and the specialty of the diagnosing clinician associated with the index outpatient visit (primary care, mental health specialty, or other medical specialty).

Sensitivity analyses that included non-LIS patients who were experiencing the coverage gap at antidepressant initiation and those who later transitioned into catastrophic coverage yielded consistent results regarding the effect of generic initiation for both outcomes, although effects of the coverage gap on adherence were slightly weaker in this larger sample. Sensitivity analysis that was limited to SSRI initiations only estimated comparable effect sizes for generic initiation with larger confidence intervals.

Discussion

Across four cohorts of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with depression and treated with antidepressants in 2007, we found that initiating the therapy with a generic antidepressant was consistently associated with increased medication adherence. This effect was stronger among the two non-LIS cohorts and strongest among the non-LIS, disabled. The beneficial effect of generic initiation was augmented for the outcome of monthly antidepressant possession while non-LIS patients were experiencing the Part D coverage gap.

Previous studies have linked out-of-pocket cost differentials between generic and branded medications to substantially increased adherence among patients starting with a generic medication for several chronic medical conditions.9 Our results suggest that beneficial effects of generic use apply to antidepressant therapy as well. However, such benefits may vary across patient populations. For example, a recent study of commercially insured patients did not find generic initiation to be associated with a greater likelihood of refill of the initially prescribed antidepressant.22 The consistent benefits of generic initiation found in our study, regardless of LIS status, may reflect the lower socioeconomic status of depressed Medicare beneficiaries and their greater sensitivity to cost differentials between generic and branded drugs. Our findings thus lend strong support for generic initiation as a means to improve antidepressant adherence among Medicare patients.

Our findings also suggest that, while the Part D coverage gap may be detrimental to antidepressant adherence, the benefits of generic initiation may mitigate the negative effects. Disabled patients not receiving LIS may be especially vulnerable to increased out-of-pocket cost during the coverage gap, and appear to benefit most from the protective effect of generic initiation.

About half of the disruption in antidepressant therapy across all patient cohorts occurred at 30 days after initiation, which, for most patients, also marked the end of the first prescription. Myriad factors may underlie the dramatic decline in adherence by the end of the first month. Beneficiaries may discontinue medication due to lack of response, side-effects, and a lack of continued medication management (dose titration, medication switch or augmentation). Physicians may not have adequately educated patients on antidepressant treatment when prescribing the medication and/or may not have followed up with sufficient intensity. Medication management accompanied by systematic clinical assessment may be important to further improve adherence 23.

In our unadjusted analysis of the LIS cohorts, disabled patients with generic initiation were shown to have worse adherence compared to disabled patients with branded initiation, which was inconsistent with findings of the adjusted analysis. Disabled patients receiving LIS were particularly vulnerable to socioeconomic disadvantages that were positively associated with generic initiation but, at the same time, negatively associated with adherence. In an unadjusted analysis, confounding by these factors may have outweighed the effect of generic initiation.

One limitation of our study is that we are unable to measure all of the clinical characteristics of patients that may influence choice of brand vs. generic antidepressant. For example, clinicians may have selectively prescribed branded antidepressants to patients who they perceived as having a greater risk of non-adherence if started on older, generic drugs. However, we do not believe this is likely to bias our estimates for several reasons. First, recent evidence shows very similar efficacy and side-effect profiles among second-generation antidepressants (including the branded drugs seen in this study).24 For a given patient who is “treatment naïve”, clinicians have little ground to predict if one antidepressant would be more effective or tolerable than another, especially among the second-generation classes.25 Thus, clinician choice of branded vs. generic initiation based on clinical characteristics may be quite limited. Second, previous studies have consistently shown that provider preferences are a much stronger determinant of medication choice than are patient clinical needs; generic initiation status may largely reflect prescriber and patient familiarity with the drug chosen and affordability to the patient.26–28

Other limitations include the following. Our data are for Medicare fee-for-service patients only; our findings may not extend to Medicare managed care patients. Like all studies that use claims data for adherence research, we based inferences on antidepressant possession, not drugs taken. As a result, the sharp decline in adherence seen at the end of the first month reflects failures to renew 30-day prescriptions and should not be interpreted as non-adherence at exactly 30 days after initiation. Our measures of antidepressant adherence reflected one dimension of guideline-concordant care, namely, continuation of therapy for an extended period of time. We did not have information on adequacy of dosage. We did not examine medication switches or augmentations, two recommended strategies when patients fail to respond to initial treatment or have serious side effects 3, 4, 29 because we were not able to determine the clinical validity of either. The clinical significance of missing a few days of antidepressant medication on a monthly basis is less clear than having a significant gap in treatment since some antidepressants have long half-lives. Thus, findings regarding monthly possession should be interpreted as secondary to those pertaining to disruption. We focused on generic (vs. branded) initiation and did not consider subsequent switches between generic and branded antidepressants, which were infrequent. We also do not have information on prescribers or the benefit design of the Part D prescription drug plans.

Conclusions

Our study provides strong evidence supporting generic initiation to improve adherence to antidepressant therapy among Medicare patients. The benefits result from the lower out-of-pocket cost associated with generic antidepressants. These benefits were augmented while patients were experiencing the coverage gap under Part D. Our findings imply that generic prescribing, a strategy within easy reach of clinicians, can be an important tool to further improve adherence to antidepressant treatment and to mitigate negative effects of the Part D benefit structure. More broadly, to assist their patients in making health care more affordable, clinicians should consider the economic impact of their treatment decisions and raise the issues of ability-to-pay with patients and discuss options. States that do not currently mandate generic substitution (unless with a DAW request by the prescriber or patient) or that require patient consent for generic substitution may consider more restrictive policies to further reap the benefits of generic use.

Supplementary Material

Take-Away Points.

Encouraging prescribers to initiate antidepressant treatment with a generic drug has the potential to improve antidepressant adherence among Medicare patients.

Starting patients with generics had benefits for antidepressant adherence by lowering out-of-pocket costs for all patients and by mitigating the effect of the Part D coverage gap faced by patients not receiving low-income subsidies.

Managed care organizations may target prescriber drug choice behaviors to further improve antidepressant adherence and effectiveness of antidepressant treatment among its members.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

Dr. Bao’s participation was supported by a career development award from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (K01 MH090087) and the Pfizer Scholar’s Grant in Health Policy. Dr. Ryan was supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (K01 HS018546). Mr. Shao was supported by a grant from the NIMH (K01 MH090087). Dr. Pincus was supported by the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Columbia University (UL1 RR024156) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Mental Health Therapeutics CERT at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, subcontract to Columbia University, funded by AHRQ) (5 U18 HS016097). Dr. Donohue was supported by grants from the AHRQ (R01HS017695), NIMH (P30 MH090333 and R34 MH082682), the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (R01-1AG034056) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1U48DP001918-01). Funding from the Pfizer Scholar’s Grant and the NIMH Advanced Research Center in Geriatric Mental Health at Weill Cornell Medical College (P30 MH085943) supported purchase of the Medicare CCW data.

References

- 1.Stagnitti MN. The Top Five Therapeutic Classes of Outpatient Prescription Drugs Ranked by Total Expense for Adults Age 18 and Older in the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, 2004. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National Patterns in Antidepressant Medication Treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Aug 1;66(8):848–856. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care. Treatment of Major Depression. Vol. 2. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3. Arlington, VA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality. Reform, the Quality Agenda and Resourse Use. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription Drug Cost Sharing: Associations With Medication and Medical Utilization and Spending and Health. JAMA. 2007 Jul 4;298(1):61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zivin K, Madden J, Graves A, Zhang F, Soumerai S. Cost-related medication nonadherence among beneficiaries with depression following Medicare Part D. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2009;17(12):1068–1076. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b972d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ventimiglia J, Kalali A. Generic penetration in the retail antidepressant market. Psychiatry. 2010;7(6):9–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Feb 13;166(3):332–337. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoadley J, Summer L, Hargrave E, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Analysis of Medicare Prescription Drug Plans in 2011 and Key Trends since 2006. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8237.pdfAccessed. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellerstein JK. The importance of the physician in the generic versus trade-name prescription decision. The Rand journal of economics. 1998;29(1):108–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Agnew-Blais J, et al. State Generic Substitution Laws Can Lower Drug Outlays Under Medicaid. Health affairs. 2010 Jul 1;29(7):1383–1390. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Fact Sheet. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit (Publication #7044-10) Menlo Park, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.BUCCANEER. Chronic Condition Data Warehouse User Guide, Version 1.8. 2011 http://www.ccwdata.org/cs/groups/public/documents/document/ccw_userguide.pdf. Accessed.

- 15.Zhang Y, Baik S, Zhou L, Reynolds C, Lave J. Effects of Medicare Part D Coverage Gap on Medication and Medical Treatment Among Elderly Beneficiaries With Depression Medicare Part D Coverage Gap and Depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2012;69(7):672–679. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Fact Sheet. Low-income Assistance under the Medicare Drug Benefit (Publication #7327-05) Menlo Park, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerner Multum Inc. [Accessed September 16, 2011];Lexicon. http://www.multum.com/Lexicon.htm.

- 18.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression in Late Life. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997 Oct 8;278(14):1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Proposed Changes to Existing Measure for HEDIS®1 2009: Antidepressant Medication Management (AMM) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional Hazards Tests and Diagnostics Based on Weighted Residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 21.BUCCANEER. [Accessed December 26, 2012];CMS Chronic Condition Data Warehouse Condition Categories. http://www.ccwdata.org/cs/groups/public/documents/document/ccw_conditioncategories.pdf.

- 22.Vlahiotis A, Devine S, Eichholz J, Kautzner A. Discontinuation rates and health care costs in adult patients starting generic versus brand SSRI or SNRI antidepressants in commercial health plans. Journal of managed care pharmacy. 2011;17(2):123–132. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harding KJ, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, Trivedi MH, Pincus HA. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1136–1143. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06282whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Second-Generation Antidepressants in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Adult Depression: An Update of the 2007 Comparative Effectiveness Review. Rockville, MD: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon G, Perlis R. Personalized medicine for depression: can we match patients with treatments? The American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1445–1455. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank R, Zeckhauser R. Custom-made versus ready-to-wear treatments: behavioral propensities in physicians’ choices. Journal of health economics. 2007;26(6):1101–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donohue JM, Morden NE, Gellad WF, et al. Sources of Regional Variation in Medicare Part D Drug Spending. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(6):530–538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1104816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heikkila R, Mantyselka P, Ahonen R. Price, familiarity, and availability determine the choice of drug - a population-based survey five years after generic substitution was introduced in Finland. BMC Clinical Pharmacology. 2011;11(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulberg HHC, Katon WW, Simon GGE, Rush AAJ. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Archives of general psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1121–1127. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.