Abstract

INTERACT is a publicly available quality improvement program that focuses on improving the identification, evaluation, and management of acute changes in condition of nursing home residents. Effective implementation has been associated with substantial reductions in hospitalization of nursing home residents. Familiarity with and support of program implementation by medical directors and primary care clinicians in the nursing home setting are essential to effectiveness and sustainability of the program over time. In addition to helping nursing homes prevent unnecessary hospitalizations and their related complications and costs, and thereby continuing to be or becoming attractive partners for hospitals, health care systems, managed care plans, and ACOs, effective INTERACT implementation will assist nursing homes in meeting the new requirement for a robust QAPI program which is being rolled out by the federal government over the next year.

Introduction

Federal health care reform in the United States is focused on the “triple aim” of improving care, improving health, and making care more affordable (1). The “Partnership for Patients” has two goals: reducing hospital acquired conditions, and reducing hospital readmissions (2). Unnecessary hospitalizations and hospital readmissions of vulnerable long-term care (LTC) residents can cause hospital-acquired complications, morbidity, mortality, and excess health care expenditures. Estimates suggest that a substantial percentage of these hospitalizations can be prevented, and result in billions of dollars in Medicare and Medicaid savings over the next several years (3–5). Some of these savings could be shared with providers to further improve care through Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and other similar strategies (6,7).

The triple aim affords geriatric health care providers a golden opportunity (8). Health care professionals who work in LTC are especially well-positioned and skilled to improve our system of care, provide leadership in new models of care, and benefit from shared savings. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has funded a major initiative that is based on this principle, supporting seven sites and close to 150 nursing homes to improve quality and reduce unnecessary hospitalizations (9).

Several care transitions interventions can help seize the opportunities that arise from health care reform. The American Medical Directors Association has made important contributions by crafting and disseminating its Transitions in Care Clinical Practice Guideline (10), and other resources directed at reducing unnecessary hospitalizations. Models of care that engage advance practice nurses to bridge the gap between the hospital and LTC setting such as the Transitional Care Model (11), or to work in teams with physicians, such as Evercare (12) have proven effective in reducing hospitalizations (13, 14). Adaption of the hospital-based project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge) (15) in the nursing home, and a palliative care consult service (16) have also shown promise in reducing hospital readmissions.

INTERACT (Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers) is a quality improvement program that has been adopted by many nursing homes throughout the United States, and is also being used in other countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom, and Singapore. Active implementation of the INTERACT program has been associated with up to a 24% reduction in all-cause hospitalizations of nursing home residents over a six-month period (17). A reduction of this magnitude would result in over $100,000 in Medicare savings annually in each nursing home that could effectively implement and sustain the program. Similar to any quality improvement initiative in the LTC setting, INTERACT requires support of the inter-professional leadership team, including directors of nursing, administrators and medical directors, as well as buy-in from primary care clinicians (including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) in order to be maximally effective. The purpose of this review is to provide these target audiences with an overview of the INTERACT program so that they can better serve as champions for this and related initiatives designed to improve care and reduce unnecessary hospitalizations and readmissions.

Development of the INTERACT Program

INTERACT was first developed in a project supported by a CMS contract to the Georgia Medical Care Foundation, the Medicare Quality Improvement Organization in Georgia. A detailed analysis of the frequency, causes, and factors associated with hospitalizations of Georgia nursing home residents (18), and an expert panel process were used to develop a toolkit which was pilot tested in three nursing homes with high hospitalization rates. The toolkit implementation was well accepted, and with the regular guidance of a project nurse practitioner, was associated with a 50% reduction in hospitalization rates, as well as a 36% reduction in the proportion of hospitalizations rated as avoidable through systematic record review by an expert clinician panel (19). With the support of The Commonwealth Fund, the INTERACT toolkit was refined through review by experts nominated by several national organizations as well as input from focus groups of nursing home providers, and then tested in a collaborative quality improvement project involving 30 nursing homes in three states (Florida, New York, and Massachusetts). Among the 25 homes that completed the project and for which baseline and intervention hospitalization rate data were available, there was a 17 % reduction in all-cause hospitalizations; among the 17 homes rated by the project team (masked to hospitalization rates) as “engaged” the reduction was 24% (17). A similar but smaller project among nursing homes in New York City also demonstrated significant reductions in hospitalizations (20). These data must be interpreted with caution, because these studies were not randomized or controlled, environmental forces of health care reform were at work, and the nursing homes were volunteers who were probably motivated early adopters with relatively high baseline hospitalization rates. But, the data do provide evidence that the program, even in the absence of strong oversight or financial incentives is feasible to implement, and that more active program implementation is associated with higher reductions in hospitalization.

Through additional support from The Commonwealth Fund and the Retirement Research Fund, INTERACT has been further refined through a second round of input from experts nominated by national organizations, as well as ongoing input received from many direct users participating in a curriculum development project. The resulting INTERACT “Version 3.0” tools are now available free for clinical use at http://interact.fau.edu. The new version of the program is currently undergoing rigorous evaluation in a randomized, controlled quality improvement implementation project involving approximately 250 nursing homes that is supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (1R01NR012936). The results of this project will be available in approximately 18–24 months.

Overview of the INTERACT Program

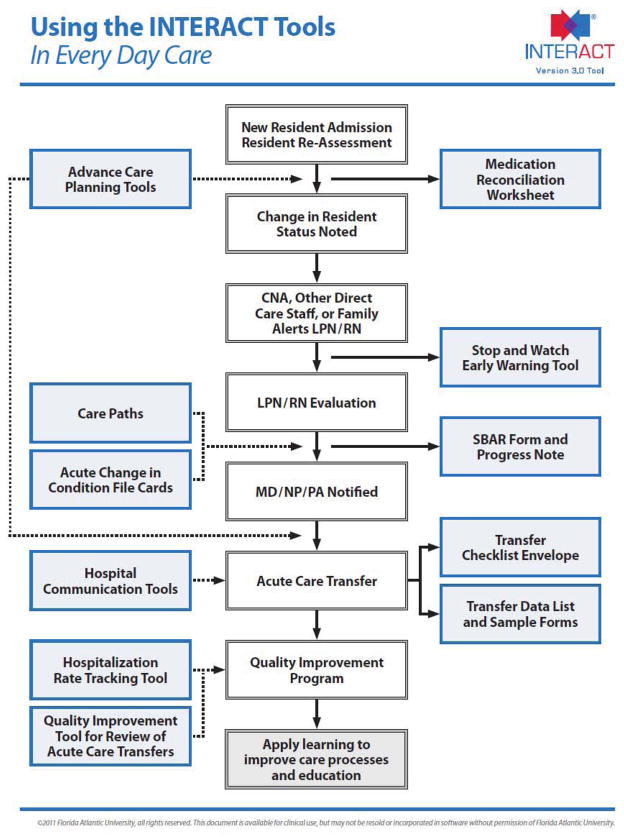

An overview of how the INTERACT program is meant to be incorporated into everyday practice is illustrated in Figure 1. The specific components of the program are described briefly in the section that follows. INTERACT has been updated from a “toolkit” to a quality improvement program that focuses on improving the management of acute changes in condition; as a result, hospitalizations are avoided in situations that can be feasibly and safely managed in the nursing home. INTERACT implementation is based on five fundamental strategies:

Figure 1. Overview of the INTERACT Program in Every Day Care.

This overview illustrates the use of the INTERACT Program in every day care in the nursing home, from the time of admission, to identifying a change in condition, and communicating and documenting relevant information; as well the quality improvement components of the program at the bottom of the figure.

Principles of quality improvement, including implementation by a team facilitated by a designated champion and strong leadership support; measurement, tracking, and benchmarking of clearly defined outcomes with feedback to all staff; and root cause analyses of hospitalizations with continuous learning and improvement based on them.

Early identification and evaluation of changes in condition before they become severe enough to require hospital transfer.

Management of common changes in condition when safe and feasible without hospital transfer.

Improved advance care planning and use of palliative or hospice care when appropriate and the choice of the resident (or their health care proxy) as an alternative to hospitalization.

Improved communication and documentation – both within the nursing home, between the nursing home staff and families, and between the nursing home and the hospital.

INTERACT Program Resources and Tools

Resources for Implementation

The INTERACT website includes announcements and articles that can be downloaded, an Implementation Guide, an Implementation Checklist that can assist nursing homes in getting started and monitoring their implementation processes, and a “Contact Us” section for questions that will be answered by a member of the INTERACT team. There are also links to a licensed printer for program materials, and an electronic interactive implementation curriculum. (Both are available at standard industry rates; the curriculum was supported by an industry-sponsored grant and may generate revenue for Florida Atlantic University - see Acknowledgement with Conflict of Interest information).

The INTERACT program and tools have been designed so that they can be incorporated into health information technology (HIT), and there is a growing demand for electronic versions of programs such as INTERACT as more and more nursing homes embrace clinical electronic health records. Incorporation of INTERACT into HIT will make it easier for direct care providers to “do the right thing at the right time,” improve communication and documentation, enable timely availability of decision support, and facilitate tracking and trending of care processes and outcomes. Information on the availability of HIT applications of INTERACT can be found on the program website.

Quality Improvement Tools

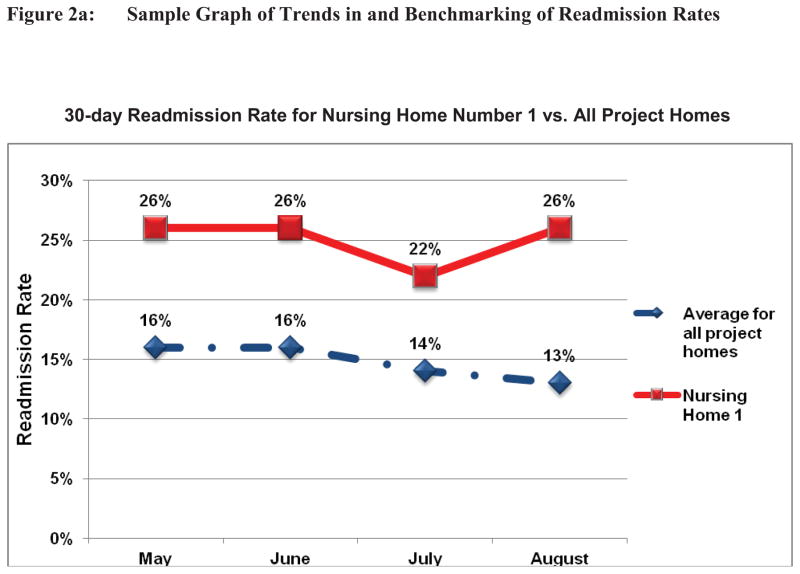

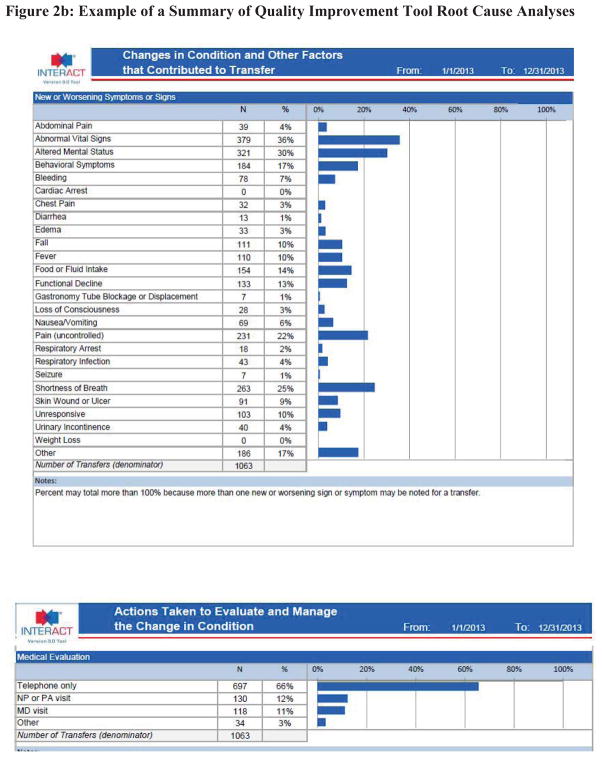

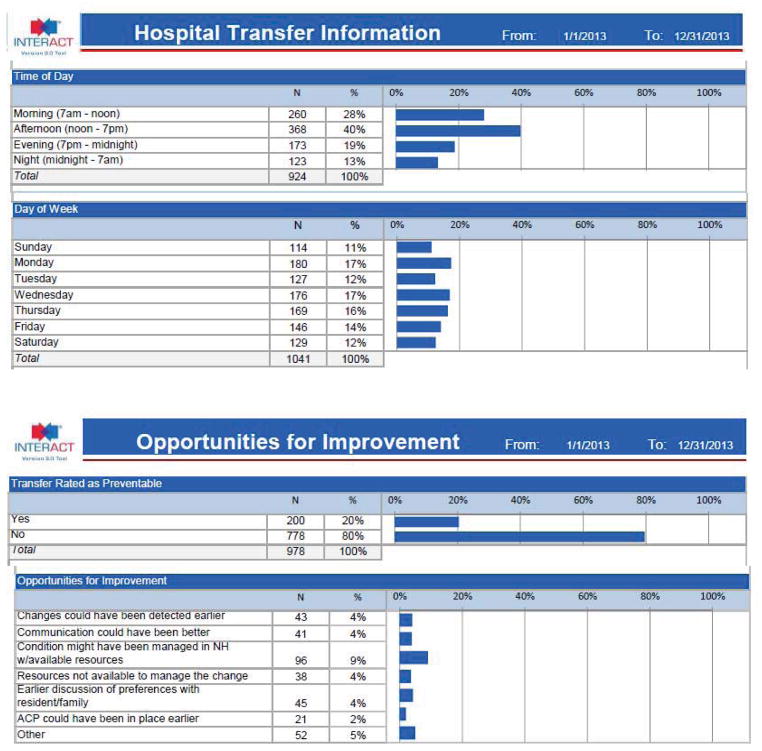

Fundamental aspects of implementing an effective quality improvement program include tracking, trending, and benchmarking well-defined process and outcome measures, and conducting and learning from root cause analyses of events. INTERACT includes a hospitalization tracking tool that can calculate hospitalization and readmission rates consistent with anticipated CMS definitions for the 30-day readmission measure for nursing homes. A similar tracking tool is available through the Advancing Excellence Campaign at http://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/; readmission rates are also calculated by the American Health Care Association for its members, and by several private vendors that provide risk-adjusted rates. These rates are also generated by electronic health records and a quality improvement software company that have a license agreement to utilize the INTERACT program. The INTERACT Quality Improvement Tool is a root cause analysis of an individual transfer; the Quality Improvement Summary Worksheet provides guidance on how to roll up the data to target education and care process improvements. The INTERACT quality improvement tools can be used to generate “quality dashboards” such as those illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of an INTERACT Quality Improvement Dashboard.

This is one example of the type of quality improvement data that can be generated from the INTERACT program. Figure 2a illustrates how 30-day readmission rates can be tracked, trended over time, and benchmarked against another group of nursing homes. Figure 2b illustrates how data from the root cause analyses of transfers using the INTERACT Quality Improvement Tool can be summarized to highlight areas for education and care process improvements. In this example summarizing over 1000 transfers, the most common changes in condition associated with transfers were abnormal vital signs, altered mental status, uncontrolled pain, and shortness of breath; about two-thirds were handled by telephone only; one-third occurred during evening or night shifts; about one-quarter occurred on a weekend; and one in five were rated as potentially preventable.

Communication Tools

INTERACT includes tools designed to improve communication and documentation within the nursing home, as well as between the nursing home and hospital. The focus of INTERACT is the management of an acute change in condition. The “STOP and WATCH” Tool was developed based on evidence that an “early warning” instrument for certified nursing assistants (CNAs) might be helpful in identifying acute changes in condition (21). The STOP and WATCH Tool uses simple language to identify common, but nonspecific changes in condition, and has been adapted by many nursing homes for use not only by CNAs, but by other direct care staff (e.g. housekeeping, dietary, rehabilitation) and by families. Completion of a STOP and WATCH Tool is meant to be a clinical alert for a licensed nurse to determine if further evaluation is necessary. When it is, INTERACT provides an “SBAR Communication Form and Progress Note,” which is meant to guide the licensed nurse through a structured evaluation of the change in condition, as well as prepare them for and structure communication with primary care clinicians. It is based on the “Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation” method that is used in many health care settings. The language in the tool has been adapted to accommodate the fact that in many states “assessment” is beyond the scope of practice of licensed practical nurses based on their state Nurse Practice Act. The tool is intended to prevent the call from an unprepared nurse that, “Mrs. Smith looks bad;” without adequate information, such calls often result, understandably, in transfer to the emergency room for further evaluation. Experience thus far with the INTERACT SBAR tool has demonstrated its value in improving communication as well as the overall professional relationship between nursing staff and medical care providers in the nursing home setting.

INTERACT tools for improving communication with acute hospitals include a checklist of key transfer documents, lists of critical data for inter-facility communication at the time of transfers, examples of forms to document these data in easily readable formats, and a tool to assist in medication reconciliation at the time of transfer to the nursing home. The “Nursing Home to Hospital Transfer Form” has been vetted repeatedly by emergency room nurses and physicians in order to insure that it includes the information they need to make an informed decision about evaluation and management of the transferred resident. The “Hospital to Post-Acute Care Transfer Form” contains critical time-sensitive information essential to provide care in the first 48–72 hours after transfer. Discharge summaries, while helpful, are usually not available in time; even when available, they often do not contain critical details that, if not attended to, can result in complications and rapid hospital readmission. The INTERACT data lists were created in recognition that many states and coalitions have their own universal transfer forms; the data lists are meant to be helpful in insuring data in these forms are complete. Many groups are working on electronic “Continuity of Care Documents” that will include these data, and federal (e.g., HL-7) data standards that will be required on such forms are currently evolving.

The INTERACT Medication Reconciliation Worksheet is intended to provide guidance for the critical process of medication reconciliation. Polypharmacy and unclear medication orders are a recipe for disaster that require meticulous attention and collaboration among nursing home nurses and medical care providers in order to prevent adverse drug events that can precipitate hospital readmission. The worksheet is meant to guide the thought process and first structures examination of the hospital medication list in order to identify clarifications needed, including unclear diagnosis or indication, uncertain dose or route of administration, stop date, hold parameters, lab tests needed for monitoring, dose different than before hospitalization, and medication duplications. The second part of the worksheet guides evaluation of medication the resident was on before hospitalization in order to insure that one or more medications, which may have been appropriately stopped or changed in the hospital, are resumed when appropriate.

The INTERACT tools for communicating with hospitals have proven popular and helpful. But, there is no substitute for in-person communication via phone, secure email, or other more individualized strategy. Not only does this insure timely communication of critical information, it fosters mutual professional understanding and respect. When patient safety is at stake, INTERACT or other similar tools are not adequate – there is no substitute for an in-person “warm handoff” to communicate the critical information.

Decision Support Tools

The INTERACT decision support tools are central to the INTERACT program and play a critical role in the management of residents with acute changes in condition and in communication between nurses and primary care clinicians in the nursing home setting. The tools are intended to help guide decisions about further evaluation of changes in resident condition, when to communicate with primary care clinicians, when to consider transfer to the hospital, and provide suggestions on how to manage some conditions in the facility without hospital transfer when it is safe and feasible. While the INTERACT Change in Condition File Cards and Care Paths are consistent with established clinical guidelines published by several national professional organizations, most are based on expert opinion as opposed to definitive scientific clinical trials. The Change in Condition File Cards concept was originally described in 1990 (22). Subsequently AMDA developed a clinical practice guideline on acute change in condition (23) and has made guidance available to nurses (“Know It All Before You Call”); both provide much more detail than the INTERACT tools, which are meant to be readily usable at the bedside.

The recommendations in the INTERACT Change in Condition File Cards and Care Paths are not meant to be fixed in stone. These tools are meant to guide clinical decision-making, not dictate it. The systematic, clearly defined approach to symptoms and signs, combined with agreement on explicit criteria for communication are more important than the specific recommendations in these tools. Nursing home clinical teams or corporations may therefore choose to modify specific criteria and recommendations for facility or corporate policies and procedures. In order for these decision support tools to be effective in everyday practice, the medical director and all primary care clinicians, including those who cover after hours, must be familiar with and support the use of these tools.

Experience in some INTERACT facilities suggests that the decision support tools, in conjunction with the INTERACT SBAR Communication Form have helped nurses become more confident in their evaluation of acute changes in condition, dramatically improved the relationship between the nursing staff and primary care clinicians, and fostered greater teamwork and mutual respect.

Advance Care Planning Tools

One of the most common reasons cited by expert clinicians in rating hospitalizations of nursing home residents potentially avoidable is that for some residents with severe end-stage illness, the risks of hospitalization outweigh the benefits (18). Moreover, family insistence on transfer to the hospital is a commonly cited reason for not attempting to manage changes in condition in the nursing home (24). Research has clearly shown that such care transitions can be burdensome in this population (25), and that implementation of advance care planning interventions can result in positive outcomes (26). While an increasing number of nursing home residents have advance directives, the process of advance care planning and updating the advance directives at critical times may not be optimal. As suggested in Figure 1, advance care planning should be undertaken, regardless of whether advance directives are already in place, at the time of admission or readmission to the facility, at regular intervals (for example at quarterly care planning meetings), and at the time of changes in condition. Residents and families may change their mind about advance care plans and directives in these situations. Thus, INTERACT Care Paths suggest updating the advance care plan as a key component of managing changes in condition, and the INTERACT Quality Improvement Tool asks about the role of advance care planning in transfers.

INTERACT advance care planning tools include a variety of tools for education of nursing home staff and residents. A fundamental theme underlying these tools is that advance care planning is a team endeavor and not just the responsibility of the primary care clinician. The Communication Guide is based largely on publications by Quill and colleagues (27, 28) and is meant for staff education, including role playing. Other INTERACT tools have been carefully constructed to be simple and illustrative in order to assist residents and families in making decisions about hospital transfer and other interventions such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and gastrostomy tube feeding (29). The Comfort Care Interventions tool includes a sample set of palliative care orders and is intended to be helpful in situations where hospices (which generally have similar order sets) are either not available or not desired by the resident or family. Many other similar resources that can complement or be used instead of INTERACT advance care planning tools are available; links to many of these resources can be found at http://interact.fau.edu.

Keys to Successful Implementation and Overcoming Common Barriers

There are three general characteristics shared by facilities that have successfully implemented the INTERACT Quality Improvement Program: executive leadership support for the program; engagement of direct care staff by the facility based INTERACT Champion (s); and what can best be described as a culture dedicated to quality improvement. These same characteristics also provide the foundation for successfully overcoming common barriers to implementation. A sample of specific strategies used by executive leaders and INTERACT champions as well as examples of nursing facility culture that supports quality improvement are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Keys to Successful INTERACT Implementation

| Examples of Successful Implementation Strategies | Examples of Common Barriers to Implementation and How They Are Overcome | |

|---|---|---|

|

Executive Leadership Support for the INTERACT Quality Improvement Program (Executive Leaders include Executive Directors, Administrators, Directors of Nursing, Corporate Leaders if applicable, Medical Directors, Clinical Pharmacists) |

Articulates vision and commitment regarding the purpose and goals for using INTERACT to the entire staff. Demonstrates commitment by:

Initiates contact with local hospitals to establish relationship and promote collaboration |

Internal resistance to change: Works with multidisciplinary team to evaluate systems and processes already in place to ensure that INTERACT tools do not duplicate other tools already in place; to determine how best to incorporate new tools and to try to “Add one tool and remove two” when possible to reduce redundant work for staff. Recognizes that organizational improvement takes time and takes the lead in sustaining focus by keeping INTERACT as agenda item at all staff and quality meetings. “We are in our survey window”: Promotes ongoing training and use of tools throughout survey window and encourages staff to use the opportunity to share their improvement efforts with surveyors during the survey “Too many things going on at once:” Develops quality agenda that includes sequential roll out of initiatives and minimizes roll out of more than one major initiative at a time. |

|

Engagement of Direct Care Staff by INTERACT Champion(s) (Selection of a Champion(s) is one of the most important decisions to be made. Successful implementation depends on the right person(s) in this role.) |

Criteria for the role of INTERACT Champion(s): Is able to motivate staff to attend training sessions and to try new tools Has experience providing training and education. Has formal or informal authority to drive/influence change in staff behavior and practice. Provides training and directs process improvement using NON PUNITIVE approach. Agrees or volunteers to be champion. Activities of effective champions:

|

“Not enough time to do the training” Builds training sessions around times that work for staff and minimizes long time off unit for all staff when possible. Uses “just in time” learning on units with clinical situations that are relevant to staff to deliver training. Delivers training according to time available; starting on one unit at a time with one tool at a time if needed. “We have no control over who goes out to the hospital…families and doctors insist” Includes family members in program by sharing decision support tools with them on admission and when there is a change in condition and encouraging use of the Stop and Watch tool by families as a method to enhance communication. Provides medical director, MDs, NPs and PAs with data regarding acute care transfer rates and summary of Quality Improvement Reviews on regular basis and seeks input on strategies to improve care relative to findings of data collection. |

| Facility Culture Dedicated to Quality Improvement | The INTERACT program is an integral component of the facility’s quality improvement activities and QAPI program INTERACT training and implementation are delivered using a non-punitive approach. When avoidable hospitalizations are identified, a spirit of inquiry by the multidisciplinary team seeks improvement, not blame |

“This is the project of the month” INTERACT training is integrated into new hire orientation and annual competency evaluations for all staff. INTERACT tools are incorporated as standard practice in the facility |

Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement: The Potential Role of INTERACT

The Affordable Care Act, in Section 6102, requires CMS to establish regulations for quality assurance performance improvement (QAPI) for nursing homes. This section further requires CMS to provide technical assistance, tools and resources for providers, in advance of CMS promulgating the new regulation. While focused on the upcoming requirement for QAPI, many facilities are simultaneously trying to position themselves to be attractive partners to ACOs. As part of that strategy, facilities are looking at ways to reduce unnecessary hospitalizations of SNF and NF residents. A QAPI questionnaire conducted by Abt Associates in 2012 revealed that many nursing home organizations do not have the infrastructure, skills, expertise, or personnel to develop and implement comprehensive, facility-wide QAPI plans (30). INTERACT may provide these organizations with a way to begin to develop their QAPI plans and become more attractive to ACOs, with an initial focus on reducing hospital readmissions that addresses many care processes throughout the entire organization.

While one major goal of the INTERACT program is to reduce unnecessary transfers to the hospital, there are other outcomes from this comprehensive approach that integrates the five elements of QAPI as outlined in CMS’ initial technical assistance (31). The current INTERACT QI program has been widely implemented across the US, and has gained attention in other countries. While there has been widespread uptake of INTERACT, in some cases facilities may only be using some of the tools and processes; therefore fidelity to the original model is a concern. It is not clear whether partial implementation of certain elements of the INTERACT QI program is effective in reducing hospitalizations or leading to other improved outcomes. Implementation of the entire program is the best strategy for meeting the intent and spirit of QAPI (see Table 2 for how certain INTERACT components and processes map to each of the five QAPI elements).

Table 2.

QAPI Elements Related to INTERACT Program Processes

| QAPI Element | INTERACT Processes |

|---|---|

| Design and Scope | Staff from all departments participate in INTERACT training Staff from all departments and families are invited to complete “Stop and Watch” tool if they detect a change in condition Residents who are hospitalized are discussed at team meetings or morning report with all department heads and other staff present. |

| Leadership and Governance | Letters of invitation to facility and corporate leadership and other materials stress the critical role of leadership engagement in INTERACT implementation. Training modules describe the vital role of leadership in providing resources for INTERACT implementation and the need for an ongoing dialogue between leadership and direct care staff. Reports from the QI review tool may be shared with leadership and the Board so that they can determine next action steps. Board members are actively engaged with direct care staff and families, are visible on the units and can articulate QAPI principles to families and staff. |

| Feedback, Data systems and Monitoring | SBAR tool enhances communication, feedback and monitoring between nurses and primary care providers. Stop and Watch tool enhances communication among CNAs, other staff, family members and nurses. Nurses provide feedback to direct care staff about their completion rates of the Stop and Watch tool, as well as the quality of the information. The QI review tool generates data and reports that are shared with direct care staff. Changes in attitudes and behaviors with respect to early identification of change in condition are monitored by supervisors and leadership, and an open dialogue is encouraged. Staff may use the transfer log and the list of people with a change in condition who are not transferred to review the decisions to transfer or not to transfer and make appropriate practice changes based on data. Input from direct care staff is encouraged, valued and accepted in a non-punitive atmosphere. |

| Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs) | Decision support tools such as the care paths can be implemented and tested in a PIP and modified to meet the specific needs of an individual facility. Data from the QI review tools may lead to prioritizing decisions about areas of concern that may merit PIPs. For example, if transfers are occurring due to bleeding and it is noted that INR values are often out of range, a PIP with respect to lab monitoring might be initiated. |

| Systematic Analysis and Systemic Action | The reports generated from QI review tools, as well as reports that could be shared based on completion of SBAR or Stop and Watch data provide patterns and help to identify fundamental, systemic issues throughout the facility such as failures in communication, weak teamwork, inadequate documentation, delays in relaying critical information across departments, etc. Networking with cross-continuum teams and hospital partners supports enhanced and seamless care across transitions and provider types that consider the nursing home part of the larger health care system. Principles in the Advance Care Planning tools support patient and family engagement, person-centered care and a focus on patient self-determination of their goals of care. Consistent implementation of those tools represents systemic action throughout the facility. |

Facilities will need to demonstrate that comprehensive programs for dementia care, fall prevention, reducing hospitalizations and others are well integrated within the larger QAPI framework. For example, principles of person-centered care that ensure all staff have specific information on each resident’s usual routines and preferences may be relevant to fall prevention, reducing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), and preventing hospital readmissions. Similarly, engaging families in care processes, whether the issue is reducing pressure ulcer risk or maintaining continence can improve many other quality outcomes simultaneously, since the care team will have more information about the person living in the nursing home. These examples illustrate the intent of two key QAPI elements: Design &Scope and Systematic Analysis & Systemic Action. Having multiple, disparate initiatives will not meet the intent of section 6102 with respect to a comprehensive, systems-based QAPI program.

Conclusion

INTERACT is a publicly available quality improvement program that focuses on improving the identification, evaluation, and management of acute changes in condition of nursing home residents. Effective implementation has been associated with substantial reductions in hospitalization of nursing home residents. Familiarity with and support of program implementation by medical directors and primary care clinicians in the nursing home setting are essential to effectiveness and sustainability of the program over time. In addition to helping nursing homes prevent unnecessary hospitalizations and their related complications and costs, and thereby continuing to be or becoming attractive partners for hospitals, health care systems, managed care plans, and ACOs, effective INTERACT implementation will assist nursing homes in meeting the new requirement for a robust QAPI program which is being rolled out by the federal government over the next year.

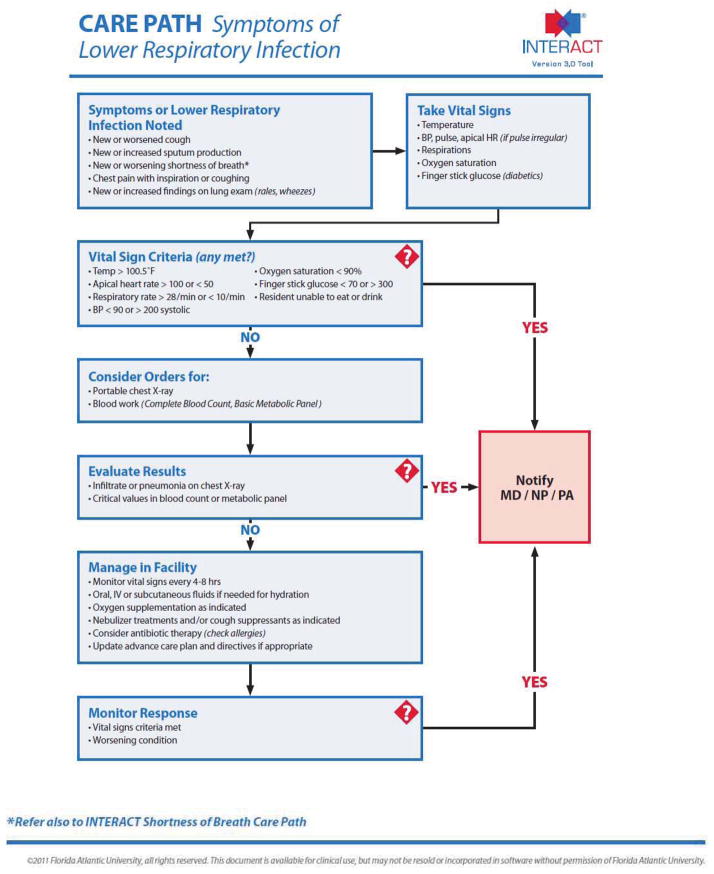

Figure 3. Example of an INTERACT Care Path.

The INTERACT care path for Symptoms of Lower Respiratory Illness is one of nine that provide guidance on evaluation and management of common conditions precipitating hospital transfers. All have been made consistent with expert recommendations; the care path shown is based on one proven to reduce hospital admissions by Loeb and colleagues in Canadian nursing homes (ref). Clinicians may elect to use alternative specific criteria in the care paths and change in condition guidance, but working with nursing staff on common approaches, language, and explicit criteria for alerts is critical to the effectiveness of the INTERACT program.

Acknowledgments

The development and testing of the INTERACT program has been supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01NR012936), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, The Commonwealth Fund, The Retirement Research Foundation, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Medline Industries, and Westcom, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost. Health Aff. 2008;27:759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [accessed December 1, 2013]; http://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov/

- 3.Walsh EG, Wiener JM, Haber S, et al. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations of Dually Eligible Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries from Nursing Facility and Home-and Community-Based Services Waiver Programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:821–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouslander JG, Maslow K. Geriatrics and the Triple Aim: Defining Preventable Hospitalizations in the Long Term Care Population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2313–2318. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spectror WD, Limcangco R, Williams C, et al. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations for Elderly Long-stay Residents of Nursing Homes. Medical Care. 2013;51:673–681. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182984bff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder SA, Frist W for the National Commission on Physician Payment Reform: Phasing Out Fee-for-Service Payment. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2029–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1302322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouslander JG, Berenson RA. Reducing unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:1165–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouslander JG. The Triple Aim: A Golden Opportunity for Geriatrics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;61:1808–1809. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [accessed December 1, 2013]; http://www.innovations.cms.gov/Files/x/rhnfr.pdf.

- 10. [accessed December 1, 2013]; http://www.amda.com/tools/clinical/toccpg.pdf.

- 11.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, et al. Transitional Care of Older Adults Hospitalized with Heart Failure: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane RL, Keckhafer G, Flood S, et al. The effect of Evercare on Hospital Use. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1427–1434. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konetzka RT, Spector W, Limcangco MR. Reducing hospitalizations from LTC settings. Medical Care Research and Review. 2008;65:40–66. doi: 10.1177/1077558707307569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuo YF, Raji MA, Goodwin JS. Association Between Proportion of Provider Clinical Effort in Nursing Homes and Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations and Medical Costs of Nursing Home Residents. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1750–1757. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkowitz RE, Fang Z, Helfand BKI, et al. Project ReEngineeing Discharge (RED) Lowers Hospital Readmissions of Patients Discharged From a Skilled Nursing Facility. J Amer Med Dir Assn. 2013;14:736–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berkowitz RE, Jones RN, Rieder, et al. Improving disposition outcomes for patients in a geriatric skilled nursing facility. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1130–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to Reduce Hospitalizations from Nursing Homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II Collaborative Quality Improvement Project. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:745–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents: Frequency, Causes, and Costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouslander JG, Perloe M, Givens J, et al. Reducing Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents: Results of a Pilot Quality Improvement Project. J Amer Med Dir Assoc. 2009;9:644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tena-Nelson R, Santos K, Weingast E, et al. Reducing Potentially Preventable Hospital Transfers: Results from a Thirty Nursing Home Collaborative. J Amer Med Dir Assn. 2012;13:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boockvar KS, Lachs MS. Predictive Value of Nonspecific Symptoms for Acute Illness in Nursing Home Residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1111–1115. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouslander J, Turner C, Delgado D, et al. Communication Between Primary Physicians and Staff of Long-Term Care Facilities. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:490–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. [accessed December 1, 2013]; http://www.amda.com/tools/cpg/acoc.cfm.

- 24.Lamb G, Tappen R, Diaz S, et al. Avoidability of Hospital Transfers of Nursing Home Residents: Perspectives of Frontline Staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1665–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell S, et al. End-of-Life Transitions among Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1212–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molloy DW, Guyatt GH, Russo R, et al. Systematic Implementation of an Advance Directive Program in Nursing Homes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1437–1444. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quill TE, Arnold R, Back AL. Discussing Treatment Preferences with Patients Who Want “Everything”. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:345–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casarett DJ, Quill TE. “I’m Not Ready for Hospice”: Strategies for Timely and Effective Hospice Discussions. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:443–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouslander JG, Krynski M, Tymchuk A. Decisions About Enteral Tube Feeding Among the Elderly. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb05951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [accessed December 1, 2013]; http://www.amda.com/advocacy/cmsqapi.pdf.

- 31. [accessed December 1, 2013]; http://cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/QAPI/NHQAPI.html.