Abstract

Introduction

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is frequently observed in urinary bladder neoplasms. In the reported study, an attempt was undertaken to determine the loss of heterozygosity of TP53(17p13), RB1(13q14), CDKN2A/ ARF(9p21) genes in DNA from neoplastic tissue, collected from patients with diagnosed urinary bladder carcinoma, and to compare the results with those of LOH evaluation in DNA isolated from urine sediment cells.

Material and methods

After isolation, DNA was amplified (PCR) by means of primers to five polymorphic microsatellite markers, the products being then separated on agarose gel. Following the method, a total of 125 DNA samples were obtained, isolated from neoplastic cells, together with 125 corresponding DNA samples, isolated from urine sediment cells.

Results

The loss of heterozygosity in at least one marker was identified in 39.2%. (49/125) of DNA from studied tumors and in 34.3% (43/125) of DNA samples, isolated from urine sediment cells. An analysis of LOH from the DNA, isolated from urine sediment cells, allowed for identification of 81.8% of neoplastic tumors with 99.7% specificity.

Conclusions

Our observations have demonstrated that LOH within 13q14, 17p13 and 9p21 loci is more often observed in clinically more advanced neoplasms. LOH in 17p13 locus is more frequently found in tumors at high histopathological stage, while in low-stage neoplasms, LOH is most often observed on chromosome 9. The high sensitivity (81.8%) and specificity (99.7%) of LOH studies in DNA, isolated from urine sediment cells, make this technique an advantageous, non-invasive method for detection and screening of bladder cancer.

Keywords: CDKN2A/ARF, TP53, RB1, bladder cancer, loss of heterozygosity, LOH

INTRODUCTION

Regarding the world statistics, urinary bladder carcinoma ranks 7th among identified malignant neoplasms [1]. When the last twenty years are taken into account, the incidence of this neoplasm has demonstrated a significant rise also in Poland. In men, the neoplasm contributes to the 4th cause of diseases and to the 6th cause of death as a consequence of malignant neoplasm, while morbidity and mortality rates in women are 3-4 times lower [2]. However, the disease is diagnosed 6-9 months later in women than in men, naturally contributing to a smaller number of five-year survivals in the former group of patients [3].

Tobacco tar products are the most significant risk factors for the development of this particular neoplasm. The major causative factors include alpha- and beta-naphthylamine, which are secreted into urine [4]. This is why the incidence of the neoplasm is 2-4 times higher in addicted smokers vs. non-smoking subjects [5]. Also very important is the fact that the occurrence of this neoplasm is associated with occupational exposure to chemical carcinogens in 60-70%. Particularly endangered occupational groups include workers of the dyeing, car building, rubber, leather, paper, gas, chemical, metal, and oil industries [6].

Urinary bladder neoplasms constitute a heterogenic group of medical conditions, which are characterized by different malignant potentials. Almost 90% of all bladder cancer cases are transitional cell carcinomas (TCC). The other 5-10% are: squamous cell carcinoma (5-10%) and adenocarcinoma (1-2%) [7, 8].

Superficial tumors account for a high percent (70-80%) of the neoplasms, originating from the urinary tract lining epithelium. They are characterized by high recurrence (50-70%) and the high percent of progression (10-30%) [9].

Molecular changes, which are at the base of urinary bladder carcinoma development, demonstrate a rather differentiated character, including both the activation of oncogenes and inactivation of suppressor genes, the products of which are the key cell cycle controlling proteins. The most frequent genetic changes in cells of the urinary bladder lining epithelium include mutations, microsatellite instability (among others, the loss of heterozygosity – LOH), as well as epigenetic changes within these genes.

There are various molecular mechanisms, leading to the development of urinary bladder neoplasms [4, 10]. Rearrangements within TP53, RB1 and PTEN genes are most frequently found in invasive neoplasms, while superficial tumors develop in result of changes in FGFR3, PIK3CA, HRAS, NRAS and KRAS genes [4, 10, 11]. Additionally, numerical and structural aberrations of chromosome 9 are observed in all the stages of clinical progression and histopathological malignancy [12, 13].

The goal of the reported study was an evaluation of LOH in TP53, RB1, and CDKN2A/ARF suppressor genes in DNA from neoplastic tissues, collected from patients with diagnosed bladder cancer, and a comparison of obtained results with the results of LOH analysis in DNA isolated from urine sediment cells.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study group

The loss of heterozygosity was evaluated in 125 patients (111 male and 14 female). The mean age of the patients was 66 years. The average observation period of the patients was 32 months. The histopathological and clinical data are shown in Table 1. Primary tumors were observed in 98 patients (78.4%) from our study group. The other cases (27/125; 21.6%) were recurrent disease 18 patients (66.6%) with stage Ta and 9 patients (33.3%) with stage higher then Ta). Forty-eight patients (38.4%) were treated by chemotherapy. Recurrence of bladder cancer in our study group appeared in 33 cases (26.4%). Death from bladder cancer occurred in 23 cases.

Table 1.

Histopathological characteristics and clinical data of 125 bladder cancer patients

| Histopathological data: | |

|---|---|

| Stage: | |

| Ta | 77 (61.6%) |

| >Ta | 48 (38.4%) |

| Grade: | |

| LG | 72 (57.6%) |

| HG | 53 (42.4%) |

| Clinical data: | |

| Primary tumors | 98 (78.4%) |

| Recurrent disease | 27 (21.6%) |

Material for studies

DNA, isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes, urine sediment cells, and tumor tissue, was submitted to molecular studies. Fragments of neoplastic tissue were obtained in the course of transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). They were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored until DNA isolation in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes in -70°C. DNA was isolated by means of a commercial kit for DNA isolation from biological remnants (Sherlock AX; A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) and stored in temperature of 4-8°C.

Blood samples were collected from patients into EDTA-K2 containing tubes and stored in refrigerator temperature until DNA isolation, performed with a MagNa Pure Compact device and a MagNa Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit I (Roche, Germany).

Urine samples (50 ml) were centrifuged (3200 RPM for 15 minutes at 10°C) and washed three times with 50 ml of PBS buffer (0.8% NaCl, KCl, 2.7, 1.8 mm KH2PO4, 8 mm Na2HPO4, pH 7,4). DNA was isolated with a Sherlock AX kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland), designed for DNA isolation from biological remnants. Isolated DNA was stored at 4-8°C.

Analysis of the loss of heterozygosity

The loss of heterozygosity in TP53, CDKN2A/ARF and RB1 genes were studied by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique. Five microsatellite markers were used for that purpose – see Table 2 for their exact characteristics. Amplification reactions were performed with particular markers, separately for DNA isolated from tumor, blood, and urine sediment cells for each of the patients, using BioRad iQ5 and LabCycler SensoQuest thermocyclers. The reaction mixture (25 µl) included 1 µl of genomic DNA (100 ng), 2.5 µl of 10x concentrated reaction buffer (700 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 166 mM (NH4)2SO4, 25 mM MgCl2), 0.5 µl 2.5 mM dNTP (TaKaRa), with 1µl of each starter (5 pmol/µl), 1.25U of Taq DNA polymerase (Novazym) 6, and 18.75 µl of water. All reactions contained a non-template control.

Table 2.

Characteristics of microsatellite markers and PCR conditions

| Marker name | Locus | Sequence of 5' >3' starters | Size (bp) | GDB and/or references | Annealing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D13S139 | 13q13.3-q13.3 | Forward: GAG GTC TCT AGC AAT AGG TAA AGG G Reverse: TCT CTG GAC GTA AGG GAT GTT TA |

127 | GDB: 190630, D13S139 | 58°C |

| D9S171 | 9p21 | Forward: AGC TAA GTG AAC CTC ATC TCT GTC T Reverse: ACC CTA GCA CTG ATG GTA TAG TCT |

157 | GDB: 188218, AFM186xc3 [14] | 58°C |

| D9S974 | 9p21-p21 | Forward: GAG CCT GGT CTG GAT CAT AA Reverse: AAG CTT ACA GAA CCA GAC AG |

190 | GDB: 434853, D9S974 [14] | 58°C |

| D9S1748 | 9p21.3-p21.3 | Forward: CAC CTC AGA AGT CAG TGA GT Reverse: GTG CTT GAA ATA CAC CTT TCC |

130 | GDB: 595589, D9S1748 [15] | 63°C |

| Intron 1 P53 | 17p13.1 | Forward: ACT CCA GCC TGG GCA ATA AGA Reverse: ACA AAA CAT CCC CTA CCA AAC AGC |

131 | Fridrich et al. [16] | 64°C |

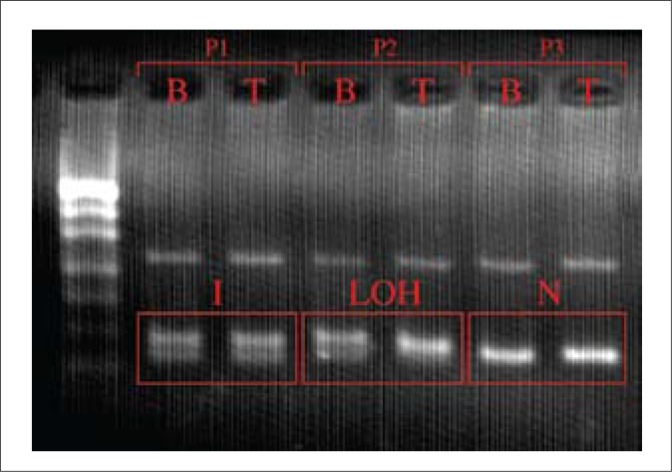

Corresponding PCR products of leukocytes, tumor tissue, and urine sediment (10 µl) were electrophoresed on 4.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Gels were evaluated by visual inspection. We compared a number of bands in corresponding blood, tumor, and urine samples and classified them as informative (two bands in blood, tumor, and urine sediment), non-informative (one band in blood, tumor, and urine sediment) and LOH (two bands in blood and one band in tumor and urine sediments) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An electrophoretic image of exemplary results of LOH for one (Intron 1 P53), out of the five studied microsatellite markers. Legend: P1, P2, P3 – numbers of patients; b – DNA isolated from peripheral blood; t – DNA isolated from neoplastic tissue; LOH – loss of heterozygosity (informative result); I – informative result; N – non-informative result.

RESULTS

Results of heterozygosity loss assessment in DNA isolated from neoplastic tissue

The loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in at least one marker was identified in 39.2% (49/125) of the studied tumors. LOH was found in 14.3% of the informative cases for TP53 (11 LOH/77) and RB1 (8 LOH/56) genes, as well as in 34.2% of the informative cases for CDKN2A/ARF gene (41 LOH/120). The highest LOH percentage was recorded for D9S1748 marker (26.3%).

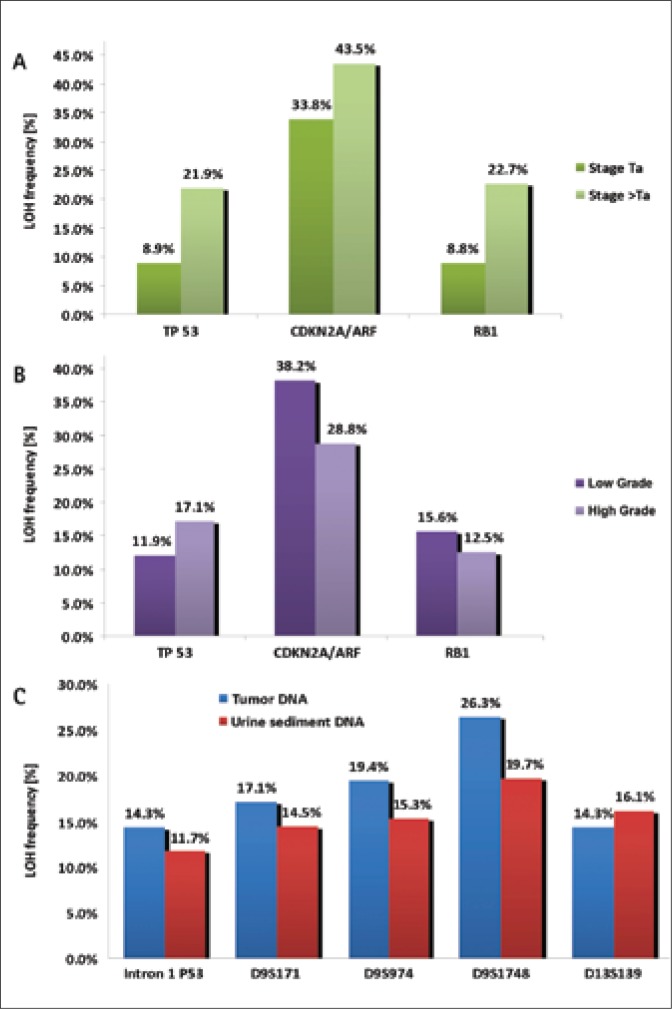

Regarding superficial tumors (Ta stage), LOH assessment results were as follows: 8.9%, 33.8%, and 8.8% of the informative cases for TP53, CDKN2A/ARF, and RB1 genes. For comparison, in higher tumor stages (>Ta), allele loss was observed in 21.9%, 22.7%, and 43.5% of the cases, informative for those genes (see Figure 2A).

Fig. 2.

A. Comparison of LOH prevalence, regarding the particular studied genes in Ta tumours with LOH prevalence in clinically more advanced tumours (>Ta). B. Comparison of LOH frequency for the particular studied genes in LG tumours with the frequency of heterozygosity loss in HG tumors. C. Comparison of LOH frequency for the particular studied microsatellite markers in DNA of neoplastic cells and of urine sediment cells.

Following LOH analysis in tumors at low-grade (LG) stage, the highest LOH frequency was noted in locus 9p21 (38.2%). In TP53 gene, the percent of loss of heterozygosity was 11.9%, while in the RB1 gene it was 15.6%. Having analyzed LOH in higher histopathological malignancy stages (HG – high grade), the loss of heterozygosity was found in 28.8% of cases in locus 9p12, in 12.5% of cases in locus 13q14 and in 17.1% of cases in locus 17p13 (Fig. 2B).

LOH assessment results in DNA isolated from urine sediment cells

LOH, in at least one marker, was identified in 34.3% (43/125) of DNA samples isolated from urine sediment cells. See Figure 2C for comparison of LOH frequency in the particular studied markers in DNA isolated from neoplastic cells and urine sediment cells.

In 13 cases, the results of LOH assessment in DNA from urine sediment did not correspond to the results of LOH analysis in tumor DNA. Twelve false negative and one false positive result were obtained. Following the obtained data, the sensitivity and specificity of the test were calculated, the test consisting in LOH evaluation in DNA isolated from urine sediment cells. The values of the parameters were 81.8% and 99.7%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

As it has previously been mentioned, there are various mechanisms of primary urinary bladder carcinoma development [4, 10, 11, 13]. The loss of heterozygosity in locus 17p13, as well as TP53 gene mutations, are frequent disorders in advanced neoplasms and in carcinoma in situ. In invasive cancers, one can also trace mutations or deletions of RB1 gene fragments. The most frequent abnormalities identified in benign tumors of the urinary bladder concerned chromosome 9.

In the course of the study, the loss of heterozygosity in at least one of the five studied markers was found in 39.2% of the evaluated tumors. That LOH prevalence was lower from that reported by Turyn et al. in their paper [14]. In their study they used a panel of 12 microsatellite markers for an analysis of LOH in DNA isolated from neoplastic tissue. They managed to identify LOH in 71% of studied cases (27/38). Similar data can be found in studies of Utting et al. [15]. They estimated LOH rate at 72% (26/36), studying the loss of heterozygosity with the use of primers for 6 microsatellite markers, localized on three various chromosomes.

Having analyzed LOH in particular loci of tumor DNA, the highest LOH intensity (34.2%) was observed in CDKN2A/ARF gene. LOH frequency for the other two genes was 14.3%. Knowles et al. provide in their work the following frequency of heterozygosity loss: 51% for CDKN2A/ARF, 15% for RB1 and 32% for TP53 [16]. The results are almost twice higher from those presented by us.

Having divided 125 studied DNA samples from urinary bladder tumors into superficial tumors (Ta) and more clinically advanced neoplasms (>Ta), it became evident that the frequencies of LOH in all the studied loci were higher in >Ta tumors. In case of RB1 and TP53 genes, the LOH percent in Ta tumors was 8.8% and 8.9%, respectively. This result is approximately 2.5 times lower from the LOH frequencies, observed for more clinically advanced tumors (21.9%; 22.7%). In case of CDKN2A/ARF gene, the difference, regarding LOH percent between Ta (33.8%) and >Ta (43.5%) tumors is not as significant. Erbersdobler et al. [17], in their studies on superficial tumors, observed LOH of 9p, 13q and 17p in 35.1%, 25%, and 27.5% of the cases. They studied a total of 40 primary neoplasms of urinary bladder. Their results correspond to the data, which are discussed in this report. A similar frequency of LOH was also presented by Turyn et al. [14]. One may then conclude that the higher the stage of clinical neoplasm progression, the higher the observed percent of changes, concerning chromosomes 13 and 17.

The material collected from neoplastic tissue, was divided and analyzed also with regards to the degree of histopathological malignancy. Here, similarly as in earlier observations, the highest LOH frequency was found in locus 9p21. It also concerns the neoplasms at LG stage, where it amounted to 38.2% and in more malignant tumors. However, in that particular case, the percent was lower, namely 28.8%. A much lower LOH frequency was observed for the other loci. In tumors at LG stage, 15.6% of LOH was noted at locus 13q14, while the percent of LOH for TP53 gene was 11.9%. In HG stages, the loss of heterozygosity was observed in 12.5% of cases in RB1gene and in 17.1% of the studied informative samples at locus 17p13.

It can be concluded from the above presented analyses that the loss of heterozygosity of TP53 and RB1 genes is more frequently observed in more clinically advanced neoplasms. At the same time, the loss of heterozygosity of TP53 gene was more often observed in tumors at higher stages of histopathological malignancy (HG). Regarding the neoplasms at LG stage, LOH was most frequently seen for chromosome 9 and 13. The discussed results of the loss of heterozygosity in DNA, isolated from neoplastic tissue, seem to confirm the fact of existence of various molecular pathways of bladder carcinoma development. It is fairly valuable information, since the patients with LOH in TP53 or RB1 genes and with a diagnosed neoplasm in Ta LG stage should become subject to more intensive follow-up, as it cannot be excluded that in case of any subsequent recurrence in these patients, a progression of the neoplastic disease may occur.

In the performed analysis of loss of heterozygosity, the highest LOH frequency in neoplastic tissue was observed in D9S1748 marker, amounting to 26.3%. The marker is localized very closely to exon 1β of CDKN2A/ARF gene [18, 19]. The exon is a promoter for ARF protein, the role of which is protection against ubiquitination of TP53 protein by its elimination from the links with HDM2. In consequence, high TP53 concentration is maintained in the cellular nucleus, which activates transcription of the genes associated with the cellular cycle arrest [20]. The loss of heterozygosity in D9S1748 marker may then be associated with the inactivation of the ARF protein. In this way, the cellular cycle will not be stopped and the process of neoplasia may go on [18, 19].

In clinical practice, urinary bladder neoplasms are identified by cystoscopy, completed by cytological evaluation of urine sediment. Unfortunately, cytology identifies non-differentiated neoplasms in higher stages of clinical progression, while cystoscopy is an invasive method for patient and rather expensive. According to Michalski et al. [21], urine cytology is characterized by high specificity (even to 100%), while its sensitivity varies within the range of 16-90%. Mao et al. demonstrated that, using this particular study, even 50% of neoplastic changes could be overlooked [22]. Therefore, finding new, non-invasive diagnostics methods could contribute to the reduction in the number of performed cystoscopies and to quicker identification of disease or its recurrence. It could also provide a direct, therapeutic advantage for the patient, while simultaneously reducing the costs of therapy. There is an obvious need to search for genetic markers, useful for detection and evaluation of the course of the disease in question. An analysis of microsatellite sequences can be a reliable, non-invasive method of detecting neoplastic cells in urine sediment. In the future, having selected an appropriate set of microsatellite markers, the method could be used as a screening examination in the group of people at increased risk (for example people with former occupational exposure) and in the group of patients to predict clinical outcome of bladder cancer.

An analysis of LOH DNA isolated from urine sediment cells was also performed within our studies. Its results were compared with the results of LOH assessment, regarding DNA isolated from tumors, collected from the same patients. The analysis allowed for identification of 81.8% of all the studied neoplastic tumors with 99.7% specificity. That result is comparable with the data presented by Dal Canto et al. [23]. However, much higher and much lower results can also be found (see Table 3). Little et al. attempted in their studies to increase the sensitivity of analysis of DNA, isolated from urine sediment cells, by raising the LOH identification threshold [24]. At first, they estimated the sensitivity of their studies at the level of 49%. They succeeded to increase its value up to 73%, however, at the expense of specificity, which dropped from 89% to 63%.

Table 3.

Comparison of data regarding the sensitivity of LOH analysis on DNA isolated from urine sediment, and presented by various authors

| Author | Test sensitivity | The number of microsatellite markers used for LOH analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Mao et al. (1996) [22] | 95% | 13 markers |

| Sourvinos et al. (2001) [25] | 93% | 15 markers |

| Dal Canto et al. (2003) [23] | 82% | 13 markers |

| Shigyo et al. (1998) [26] | 70% | 5 markers |

| Littel et al. (2005) [24] | 49% | 7 markers |

| Turyn et al. (2006) [14] | 39% | 12 markers |

| Utting et al. (2002) [15] | 27% | 6 markers |

Such extensive differences in the sensitivity of analysis of urine sediment cells, as presented by various authors, may result from the fact that the sediment is a mixture of many different cells. In addition to neoplastically-changed cells, there are also normal epithelia, desquamated from the urinary tract and the bladder, as well as leucocytes. It may contribute to a higher percent of false-negative results.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of the loss of heterozygosity of DNA, isolated from urine sediment cells, is probably a more reliable method than the cytological study of urine; however, the sensitivity of the presented test, which was obtained in the course of the reported study (81.8% of tumors with informative results for studied markers), is not satisfactory. The studies reported in this paper may then be approached as pilot studies, testing a panel of 5 microsatellite markers. A selection of a more appropriate set of markers may then be of key importance to regard the analysis of microsatellite sequences as a reliable, non-invasive method of neoplastic cell identification in urine sediment.

Acknowledgements

The reported study was carried out within Research Project No. 2P05C07630 from the State Committee of Scientific Research. Our studies and applied procedures were approved by the Committee of Ethics at the Medical University of Łódź (Document No. RNN/215/10/KE).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng L, Zhang S, MacLennan G, et al. Bladder Cancer: translating molecular genetics insights into clinical practice. Hum Pathol. 2011;42(4):455–481. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zatoński W. Nowotwory złośliwe w Polsce w 2006 roku. Warsaw: The National Register of Neoplasms, The M. Skłodowska-Curie Centre of Oncology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute. Priorities of the Kidney/Bladder Cancers Progress Review Group. http://planning.cancer.gov/pdfprgreports/2002kidneyreport.pdf (03.03.2009).

- 4.Pasin E, Josephson D, Mitra A, Cote R, Stein J. Superficial bladder cancer: An update on etiology, molecular development, classification and natural history. Rev Urol. 2008;10(1):31–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombel M, Soloway M, Akaza H, et al. Epidemiology, Staging, Grading and Risk Stratification of Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol Suppl. 2008;7:618–626. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zlotta AR, Cohen SM, Dinney C, Droller M, et al. BCAN Think Tank session 1: Overview of risks for and causes of bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(3):329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badalament RA, Schervish EW. Rak pęcherza moczowego. Współczesne metody rozpoznawania i leczenia. [Bladder cancer. Current methods of diagnosis and treatment] Medycyna po dyplomie. 1997;6(2):167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford JM. The origins of bladder cancer. Lab Invest. 2008;88(7):686–693. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs B, Lee C, Montie J. Bladder cancer in 2010. How far we come. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:244–272. doi: 10.3322/caac.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goebell PJ, Knowles MA. Bladder cancer or bladder cancer? Genetically distinct malignant conditions of the urothelium. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(4):409–28. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowles MA. Molecular subtypes of bladder cancer: Jekyll and Hyde or chalk and cheese? Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(3):361–73. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berggren P. Molecular changes in the tumor suppressors genes p53 and CDKN2A/ARF in human urine bladder cancer; Stockholm: 2002. pp. 23–28. chapt. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles MA. What we could do now: molecular pathology of bladder cancer. Mol pahtol. 2001;54:215–221. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.4.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turyn J, Matuszewski M, Schlichtholz B. Genomic instability analysis of urine sediment versus tumor tissue in transitional cell carcinoma of the urine bladder. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Utting M, Werner W, Dahse R, Schubert J, Junker K. Microsatellite analysis of free tumor DNA in urine, serum and plasma of patients: A minimally invasive method for the detection of bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knowles MA, Elder P, Williamson M, Cairns J, Shaw M, Law M. Allotype of human bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:531–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erbersdobler A, Friedrich M, Schwaibold H, Huland H. Microsatellite alterations at chromosomes 9p, 13q, and 17p in nonmuscle-invasive transitional cell carcinomas of the urine bladder. Oncol Res. 1998;10(8):415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smeds J, Berggren P, Ma X, Xu Z, et al. Genetic status of cell cycle regulators in squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus: the CDKN2A (p16(INK4a) and p14(ARF)) and p53 genes are major targets for inactivation. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(4):645–55. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berggren P, Kumar R, Sakano S, et al. Detecting Homozygous Deletions in the CDKN2A(p16INK4a)/ARF(p14ARF) Gene in Urinary Bladder Cancer Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vousden K, Lane D. p53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(4):275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michalski W, Demkow T. Przegląd wybranych markerów diagnostycznych i prognostycznych u chorych na raka pęcherza moczowego. [A review of selected diagnostic and prognostic markers in patients with bladder cancer] Urol Pol. 2007;60:2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao L, Schoenberg MP, Scicchitano M, et al. Molecular detection of primary bladder cancer by microsatellite analysis. Science. 1996;271:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dal Canto M, Bartoletti R, Travaglini F, et al. Molecular urine sediment analysis in patient with transitional cell bladder carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2003;23(6D):5095–5100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little B, Hughes A, Young M, O'Brien A. Use of polymerase chain reaction analysis of urine DNA to detect bladder carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2005;23(2):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sourvinos G, Kazanis I, Delekas D, Cranidis A, Spandidos D. Genetic detection of bladder cancer by microsatellite analysis of p16, RB1 and p53 tumor suppressor genes. J Urol. 2001;165:249–252. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shigyo M, Sugano K, Taniguchi T, et al. Allelic loss on chromosome 9 in bladder cancer tissues and urine samples detected by blunt-end8 single-strand DNA conformation polymorphism. Int J Cancer. 1998;78(4):425–429. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981109)78:4<425::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]