Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study is to present the oncologic outcomes and to determine prognostic parameters of overall (OS), cancer specific survival (CSS), disease progression free survival (DPFS) and biochemical progression free survival (BPFS) after surgery for pT3a prostate cancer (PCa).

Material and methods

Between 2002 and 2007, a pT3a stage after radical prostatectomy was detected in 126 patients at our institution. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to calculate OS, CSS, DPFS and BPFS. Cox regression was used to identify predictive factors of survival.

Results

Five-year OS, CSS, DPFS and BPFS rates were 96%, 98.7%, 97.3% and 60%, respectively. Among patients with prostate specific antigen (PSA) <10 ng/ml and PSA >20 ng/ml the 5-year OS was 98.8% and 80%, respectively, whereas 5-year BPFS was 66% and 16.6%, respectively. Survival was different when comparing surgery Gleason score ≤7 and ≥8. 5-year OS and BPFS were 98% vs. 80%, and 62.6% vs. 27.3%, respectively. Specimen Gleason score and preoperative PSA were significant predictors of BPFS. The risk of biochemical progression increased up to 2-fold when a Gleason score ≥8 was present at final pathology.

Conclusions

In locally advanced pT3 PCa, surgery can yield very good cancer control and survival rates especially in cases with PSA <10 ng/ml and Gleason score ≤7. PSA and Gleason score after surgery are the most significant predictors of outcomes after radical prostatectomy.

Keywords: prostate cancer, locally advanced, surgery, outcome

INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, of the definition of the optimal treatment in high risk prostate cancer (PCa) is among the topics that are of most interest to the urological community, but consensus in this field is still not reached. Up until a decade ago, most T3 PCa patients underwent radiotherapy (RT) or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) or a combination of both, while only about 36% were initially treated by surgery [1]. Recent publications have revealed that in selected cases of locally advanced and high-grade tumors, surgery as monotheraphy or as part of a multimodality treatment may be used instead of RT [2]. The high risk PCa population, usually described as having prostate specific antigen (PSA) >20 ng/ml, biopsy Gleason score ≥8 or an advanced clinical stage (T3a-b) is however not homogeneous [3]. Recent studies have shown that treatment outcomes can vary widely, depending on whether patients present with only one, or rather a combination of those high-risk factors, with the latter patients having the worst outcomes [4–7]. It is still unclear which patients, according to the accepted predictors of aggressive disease behavior, are the best candidates for surgery, mostly due to the lack of data on long-term oncologic outcomes and randomized clinical trials. According to the European Association of Urology guidelines, surgery is optional in patients presenting with cT3a, Gleason score 8-10 or PSA >20 ng/ml, and life expectancy of more than 10 years [8]. Even in highly selected patients with cT3b or cN1 PCa, surgery may be offered as part of a multimodality approach [8]. We believe that radical prostatectomy is indeed an appropriate treatment for more aggressive PCa, but data for confirming that are still insufficient.

The purpose of this study is to present the oncologic outcomes of patients having pT3a PCa after surgery, including overall survival (OS), disease progression free survival (DPFS), cancer specific survival (CSS) and biochemical progression free survival (BPFS). Furthermore, we aimed to analyze predictive parameters in survival.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

During the period 2002-2007, 840 radical retropubic prostatectomies (RRP) were performed in our institution. 133 of them had pathological stage T3a (15.8%). Seven patients were lost for additional follow-up. Final analysis was carried out using the data of 126 patients with complete follow-up. No patients received neoadjuvant treatment. The last PSA before biopsy was used for analysis.

Biopsy Gleason score ≥7 or PSA >10 ng/ml or clinical stage T3 were indications for lymph nodes removal. 71 of 126 (56.3%) patients of our study population had such criteria. For other 55 (43.7%) patients, a lymphadenectomy was not performed.

The pathological examination of radical prostatectomy specimens and bilateral pelvic lymph nodes were performed by one dedicated uropathologist.

Serum PSA and physical examination were performed every 3 months in the first year after surgery, every 6 months in the second and third years, and annually thereafter. The PSA data were taken from outpatient clinic files. Data about patients’ death and cause of death were received from the National Cancer Registry.

OS was defined as the time from surgery to death from any cause. CSS was defined as the time from surgery to death caused by PCa or complications of this disease. Biochemical progression was defined as the time from surgery to PSA level ≥0.2 ng/ml confirmed by repeated test. Disease progression was defined as the development of either local disease recurrence or distant metastasis. Adjuvant treatment was defined as either ADT or RT given within 3 months after surgery. Salvage treatment was defined as any kind of therapy (RT or ADT) given later than 3 months after surgery.

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to calculate the OS, CSS, DPFS and BPFS. The differences were tested by log-rank test. The Cox regression analysis was used to determine the prognostic parameters for survival.

RESULTS

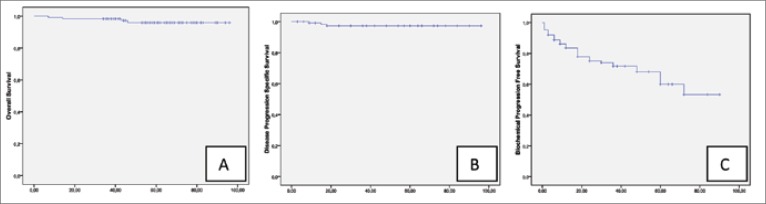

An overview of the patients’ preoperative and postoperative parameters is shown in Table 1. The median follow-up was 56 months (range 7-96). 5-year rates for OS, CSS and DPFS in our study cohort were 96%, 98.7% and 97.3%, respectively (Fig. 1A, B). Five-year BPFS was 60% (Fig. 1C). Cox regression analysis revealed that from all parameters (age, biopsy and surgery Gleason score, surgical margin and lymph nodes status, preoperative PSA level) only preoperative PSA (p = 0.037, HR 1.054, 95% CI 1.003-1.108) and postoperative Gleason score (p = 0.008, HR 2.05, 95% CI 1.202- 3.506) had an impact on biochemical relapse (Table 2). According Cox regression analysis, there were no parameters influencing overall and cancer specific mortality or disease progression.

Table 1.

Patient characteristic.

| Parameter | N = 126 |

|---|---|

| Median age (yr) ( range) | 66.5 (49-78) |

| Median PSA (ng/ml) (range) | 7.63 (0.68-39.89) |

| Mean biopsy Gleason (range) Gleason ≤6 Gleason 7 Gleason ≥8 |

6.4 (6-9) 68.3% 26.0% 5.7% |

| Mean surgery Gleason (range) Gleason ≤6 Gleason 7 Gleason ≥8 |

6.9 (6-9) 19.8% 71.4% 8.8% |

| R (%) | 54.2% |

| N+ (rate) | 2.8% (2/71) |

| PSA relapse | 29.6% |

| Deaths (rate) | 3.2% (4/126) |

| Deaths from cancer (rate) | 0.8% (1/126) |

| Median follow-up (mo) (range) | 56 (7-96) |

R – Positive surgical margins, PSA – prostate specific antigen

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for overall survival (A), disease progression free survival (B) and biochemical progression free survival (C) in all study patients.

Table 2.

Cox multivariate regression analysis of preoperative and histopathologic parameters for biochemical progression free survival.

| Parameter | Biochemical Progression Free Survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age | 1.050 | 0.967-1.140 | 0.249 |

| Lymph node | 0.378 | 0.038-3.768 | 0.407 |

| Pre operative PSA | 1.054 | 1.003-1.108 | 0.037 |

| Surgical margins | 0.681 | 0.276-1.680 | 0.405 |

| Biopsy Gleason score | 1.355 | 0.839-2.189 | 0.214 |

| Surgery Gleason score | 2.053 | 1.202-3.506 | 0.008 |

Lymph nodes status. A mean of 6.3 (range 1-15) lymph nodes were removed, and the overall positive node detection rate was 2.8%. Because of this small number of positive nodes we could not perform analysis in survival.

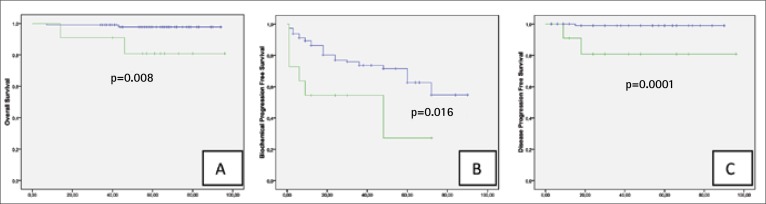

Gleason score. The mean surgery Gleason score was significantly worse when after biopsy (6.4 vs. 6.9, p = 0.001). Gleason score upgrading was detected in 51.2% of cases, downgrading in 4.9% of cases. The Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrates significant differences between Gleason ≤7 and ≥8 for OS (Fig. 2A), CSS (Fig. 2B), DPFS and BPFS (Fig. 2C) in the study population. The estimated 5-year OS, CSS, DPFS and BPFS rates in patients with Gleason score ≥8 were 80.8%, 88.9%, 80.8% and 27.3%, respectively, while in Gleason score ≤7, 5-year OS, CSS, DPFS and BPFS were 97.8%, 100%, 99% and 62.6%%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test for overall survival (A), biochemical progression free survival (B) and disease progression free survival (C) stratified for prostate Gleason score.

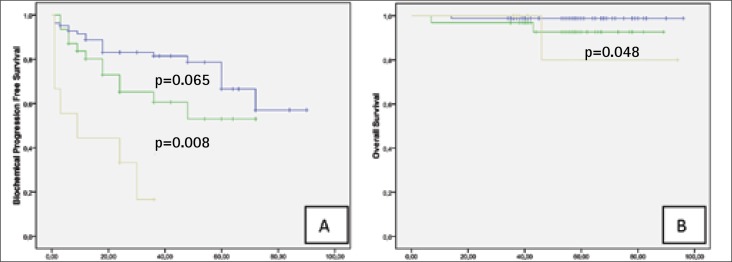

Preoperative PSA. Preoperative PSA <10 ng/ml had 67.2%, PSA 10-20 ng/ml – 25.6% and >20 ng/ml – 7.2% of study patients. There were no differences in 5-year DPFS comparing groups according PSA level but at PSA <10ng/ml 5-year OS, CSS and BPFS rates was significantly higher when in patients group with PSA >20 ng/ml (Fig. 3A–B). In all oncologic outcome parameters according Kaplan-Meier analysis there were no difference between groups with PSA <10 and 10-20 ng/ml (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test for biochemical progression free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified for prostate specific antigen level.

Table 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis results in overall (OS), cancer specific (CSS), disease progression free (DPFS) and biochemical progression free survival (BPFS) according prostate specific antigen (PSA) and Gleason score subgroups.

| Parameter | 5-year OS (%) | 5-year CSS (%) | 5-year DPF S (%) | 5-year BPF S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSA <10 ng/ml | 98.8%* | 100%* | 98.7% | 66.6%* |

| PSA 10-20 ng/ml | 92.7% | 100%‡ | 96.6% | 53.0%‡ |

| PSA >20 ng/ml | 80.0%* | 80%*‡ | 88.9% | 16.7%*‡ |

| Gleason score 6-7 | 97.8%† | 100%† | 99%† | 62.6%† |

| Gleason score 8-9 | 80.8%† | 88.9%† | 80.8%† | 27.3%† |

p < 0.05 between different parameters

p < 0.05 between different parameters

p < 0.05 between different parameters

Post-operative treatment. Patients with pT3a PCa are generally considered at risk for disease progression. Therefore, adjuvant or salvage treatment (RT or ADT) are often applied. In our study population, additional treatment was given to 21.4% of cases. ADT received 14.3%, RT – 5.5% and RT with ADT was applied to 1.6% of patients. At final visit the PSA >0.2 ng/ml was detected in 23.2% of cases

Surgical margins status. Positive surgical margins rate was 54.2%. In Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analysis this parameter did not have significant impact in survival, disease progression or biochemical relapse.

DISCUSSION

During the last decade, the discussion about the role of surgery in locally advanced PCa became increasingly active. Before that time, treatment of locally advanced PCa was mostly in hands of radiation oncologists [1]. Such discussion became possible for several reasons: successful treatment of high risk PCa with RT monotherapy requires high radiation doses (74-80Gy), leading to higher rates of adverse events. On the other hand, recent studies demonstrate outcomes after surgery that can be compared with radiation therapy +/- ADT [2, 9–12]. Our single center study shows that surgical treatment may indeed be a reasonable treatment option in locally advanced pT3a PCa with 96% OS, 98.7% CSS, 97.3% DPFS and 60% BPFS at the 5-year follow-up mark. The survival rates of the pT3a patients in our study are similar to those reported by Hsu et al. in a study of 200 patients with unilateral cT3a treated by surgery. They also showed that progression-free survival rates of patients with pT3a PCa did not differ significantly from those with pT2 disease [7]. Some other authors have also reported their outcomes of surgical treatment for T3 PCa. Summarizing those results, 5-year CSS and OS rates varied from 85 to 100% and from 75 to 98%, respectively [9–12]. Direct comparison of the outcomes of surgery and radiation are inadequate because of inherent selection biases, Gleason score upgrading or stage migration after surgery. Nevertheless, this issue partially could be solved using data from the RTOG trials, which compared RT vs. a combined approach using RT and ADT [13]. In a review of those RTOG trials, different PCa risk groups were identified with group 2 (Gleason ≤6, T3Nx-N1; or Gleason 7, T1-2Nx) and group 3 (Gleason 7, T3Nx-N1; or Gleason ≥8, T1-2Nx) most closely corresponding with our study population. After radiation, the 5-year OS and CSS rates were 82% and 94% for group 2, and 68% and 83% for group 3 respectively [13]. Outcomes from another long-term study comparing RT vs. RT with concomitant ADT were reported by Bolla et al. [14]. In the EORTC-trial, 412 patients with locally advanced PCa were treated with RT alone or in combination with ADT. Five-year OS and CSS rates were respectively 62 and 79% in the radiation alone group. Better survival was reported in combination group: 78% and 94%, respectively. Our study data showed a comparable 98.7% 5-year CSS, similar to RT and ADT combination therapy.

The group of locally advanced PCa is heterogeneous. PSA and specimen Gleason score have a significant impact on the survival analysis. According to our study, patients with a PSA <10 ng/ml had significantly better OS, CSS and BPFS when compared to those with a PSA level >20 ng/ml (log rank p = 0.048, p = 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively). Patients with a PSA level of 10 to 20 ng/ml did not have significantly different OS, CSS or BPFS when compared to PSA <10 ng/ml but they have different CSS and BPFS when compared to PSA >20 ng/ml (log rank p = 0.04, p = 0.008, respectively). In the study cohort, PSA had no impact on DPFS. Some recent studies studied the role of PSA in survival and biochemical or disease progression [5, 15, 16]. All authors agreed that PSA >20 ng/ml indeed could be considered as a high risk factor. Our study data support this finding.

Gleason score has long been recognized as an important risk indicator for worse outcome. In locally advanced PCa, biopsy Gleason sum has a tendency to be upgraded, and in our series upgrading was indeed frequent (up to 50%). In fact, in our study, specimen Gleason score was identified as one of the most important outcome predictor. Our data showed a significant difference between survival curves (OS, CSS, DPFS and BPFS) comparing Gleason score 6-7 vs. 8-9. Patients with postoperative Gleason ≥8 are associated with a 2-fold increased risk for biochemical relapse. Most of the published studies confirm that Gleason score 8-10 indeed determines worse biochemical or disease free survival both in locally advanced and organ confined disease [17–20]. Our study shows that 5-year OS, CSS, DPFS or BPFS rates in Gleason score 8-9 PCa were 80.8%, 80%, 80.8% and 27.3% compared to 97.8%,100%, 99% and 62.6% if Gleason score was 6-7. However, significant survival differences between high and moderate grade PCa does not mean that a more advanced tumor grade is a contraindication for surgery. Tewari et al. pointed out that long term results in high grade PCa after surgery are better when comparing surgically treated patients with those who underwent RT or conservative treatment [21]. In 453 patients with biopsy Gleason 8-10, median OS after surgery was 9.7 years, while for radiation this was 6.7 years and for conservative treatment 5.2 years. The risk of cancer-related death after surgery was 68% lower than after conservative treatment and 48% lower than after RT.

Generally, it is accepted that patients with locally advanced PCa at final histology are ideal candidates for additional treatment after surgery. Up until now, there is still no consensus which treatment modality – RT, ADT or a combination – is the best choice to decrease the risk of disease progression following surgery. In the present study, only 21.4% of cases received adjuvant or salvage treatment and it demonstrate that RRP alone in pT3a PCa could yield very good cancer control especially in cases with PSA <10 ng/ ml and Gleason score ≤7.

With 5-year OS and CSS of 96% and 98.7%, our study supports the notion that radical prostatectomy with adjuvant or salvage therapy when needed may provide comparable outcomes as RT plus ADT in locally advanced PCa, especially in pT3a. However, this finding should be confirmed in prospective, randomized studies.

CONCLUSIONS

In locally advanced pT3 PCa, surgery can yield very good cancer control and survival rates especially in cases with PSA <10 ng/ml and Gleason score ≤7. PSA and Gleason score after surgery are the most significant predictors of outcomes after radical prostatectomy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meng MV, Elkin EP, Latini DM, et al. Treatment of patients with high risk localized prostate cancer: results from cancer of the prostate strategic urological research endeavor (CaPSURE) J Urol. 2005;173:1557–1561. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154610.81916.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Poppel H, Joniau S. An analysis of radical prostatectomy in advanced stage and high-grade prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;53:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich A, Bolla M, Joniau S, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer 2011. www.uroweb.org/nc/professional-resources/guidelines/online. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Yossepowitch O, Eggener SE, Serio AM, et al. Secondary therapy, metastatic progression, and cancer-specific mortality in men with clinically high-risk prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;53:950–959. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spahn M, Joniau S, Gontero P, et al. Outcome predictors of radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/ ml: a European multi-institutional study of 712 patients. Eur Urol. 2010;58:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mian BM, Troncoso P, Okihara K, et al. Outcome of patients with Gleason score 8 or higher prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy alone. J Urol. 2002;167:1675–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu C-Y, Joniau S, Oyen R, et al. Outcome of surgery for clinical unilateral T3a prostate cancer: a single-institution experience. Eur Urol. 2007;51:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localized disease. Eur Urol. 2011;59(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber GS, Thisted RA, Chodak GW, et al. Results of radical prostatectomy in men with locally advanced prostate cancer: multi-institution pooled analysis. Eur Urol. 1997;32:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Ouden D, Hop WCJ, Schroder FH. Progression in and survival of patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (T3) treated with radical prostatectomy as monotherapy. J Urol. 1998;160:1392–1397. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199810000-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez de la Riva SI, Lopez-Tomasety JB, et al. Radical prostatectomy as monotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer (T3a):12 years follow-up. Arch Esp Urol. 2004;57:679–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward JF, Slezak JM, Blute ML, et al. Radical prostatectomy for clinically advanced (cT3) prostate cancer since the advent of prostate-specific antigen testing: 15-year outcome. BJU Int. 2005;95:751–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roach M, Lu J, Pilepich MV, et al. Four prognostic groups predict long-term survival from prostate cancer following radiotherapy alone on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:609–615. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolla M, Collette L, Blank L, et al. Long-term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yossepowitch O, Eggener SE, Serio AM, et al. Secondary therapy, metastatic progression, and cancer-specific mortality in men with clinically high-risk prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;53:950–959. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephenson AJ, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, et al. Prostate cancer specific mortality after radical prostatectomy for patients treated in the prostatespecific antigen era. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4300–4305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mian BM, Troncoso P, Okihara K, et al. Outcome of patients with Gleason score 8 or higher prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy alone. J Urol. 2002;167:1675–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donohue JF, Bianco FJ, Jr, Kuroiwa K, et al. Poorly differentiated prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy: long-term outcome and incidence of pathological downgrading. J Urol. 2006;176:991–995. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manoharan M, Bird VG, Kim SS, et al. Outcome after radical prostatectomy with a pretreatment prostate biopsy Gleason score of 8. BJU Int. 2003;92:539–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serni S, Masieri L, Minervini A, et al. Cancer progression after anterograde radical prostatectomy for pathologic Gleason score 8 to 10 and influence of concomitant variables. Urology. 2006;67:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tewari A, Divine G, Chang P, et al. Long-term survival in men with high grade prostate cancer: a comparison between conservative treatment, radiation therapy and radical prostatectomy-a propensity scoring approach. J Urol. 2007;177:911–915. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]