Abstract

Introduction

Acute epididymo-orchitis (AEO) is an acute inflammatory disease of the epididymis and ipsilateral testis. Treatment should be started immediately after diagnosis and includes antibiotics, analgesics, and, if necessary, surgery.

Materials and methods

After AEO diagnosis, patients were treated conservatively with analgesics and antibiotics. If no clinical improvement was observed within the first 48-72 hours of conservative treatment, patients underwent surgery. Depending on examination results, 254 patients (pts.) were divided into three groups: 1) with palpable differences between the epididymis and testis (E/T+), and without neither hydrocele, local softening (malacia), nor abscess of the epididymis or testis; 2) with E/T+, absence of malacia, presence of hydrocele, and none, one, or a few small abscesses within the epididymis/testis and 3) without palpatory differentiation between the epididymis and testis, with or without malacia, with hydrocele, and none, one, or more abscesses of any size. We analyzed the clinical outcomes in each group.

Results

All of patients from the first group were successfully treated with antibiotics. In the second group, conservative treatment was effective in 70 pts. (85.4% of this group), but the other 12 pts. (14.6%) did not show clinical improvement and underwent organ-sparing surgery. The majority of patients from the third group did not demonstrate an objective response to antibacterial treatment during the first 48-72 hours and, therefore, underwent surgery. Based on examination results and clinical outcomes we developed a classification system for AEO, which divides AEO into three stages and recommends an approach to its treatment.

Conclusions

Our classification is able to systematize treatment approaches in patients with AEO.

Keywords: epididymo-orchitis, hydrocele, abscess, scrotal ultrasound investigation

INTRODUCTION

Acute epididymo-orchitis (AEO) is an acute inflammatory disease of both the epididymis and ipsilateral testis. It most often presents unilaterally and occurs because of a specific or nonspecific urinary tract infection (urethritis, prostatitis, or cystitis) that seeds to the epididymis and testis through the lymphatic vessels or ductus deferens. It can also be the result of viral infections, trauma, autoimmune disorders, or even amiodarone use. A bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), transurethral diagnostic or surgical manipulations, surgeries on the lower urinary tract, or even different urogenital malformations are also thought to play a significant role in the etiology of AEO.

Most commonly, it is the epididymis that first evolves with a proliferative inflammatory process, and then the inflammation extends to the testis. In the exudative inflammatory phase, a serous fluid collects around the testis and causes enlargement of scrotum – a reactive hydrocele. AEO is always accompanied by a subfebrile or febrile temperature and intense scrotal pain, which may radiate up along the funiculus spermaticus. Diagnostic procedures include physical examination, standard laboratory tests, scrotal ultrasound investigation, and microscopic examination of urethral discharges if they are present. Treatment should be started immediately after diagnosis of AEO and should include antibiotics, analgesics, and, if necessary, surgery.

The aim of this investigation was to determine a treatment approach for AEO based on a patient's examination results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 2006 and 2010, 254 patients (pts.) with AEO were treated at our clinic. Patients with AEO due to urogenital tuberculosis or those with autoimmune or viral orchitis were not included in our investigation because of their need for different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

After the initial physical examination and scrotal ultrasound investigation we registered clinical signs, such as: body temperature dynamics, palpable differences between epididymis and testis (E/T + ), local softening (malacia) of the epididymis or testis, presence or absence of hydrocele as well as presence or absence and size of abscesses in the epididymis or testis based on results of scrotal ultrasound investigation.

Patients were divided on three groups:

Group I, 74 pts. (29.1%) with palpable differences between epididymis and testis (E/T + ), and without neither hydrocele, malacia, nor abscesses in the epididymis or testis.

Group II, 82 pts. (32.3%) with E/T+, absence of malacia, presence of hydrocele, and no, one, or a few little abscesses up to 0.5 cm in diameter each one.

Group III, 98 pts. (38.6%) without palpatory differentiation between epididymis and testis (E/T–), with or without local softening (malacia), and with hydrocele. This group was divided on two subgroups depending the absence or presence and size of abscesses in epididymis/testis:

IIIA, 45 pts. with none, one, or a few little abscesses up to 0.5 cm in diameter each one;

IIIB, 53 pts. with one or more abscesses larger than 0.5 cm in diameter each one.

The principal feature of patients from the IIIB subgroup was the presence of local softening (malacia) in the scrotum as a consequence of purulent destruction of the epididymis/testis. Malacia in these patients was absent only in cases of large hydrocele and inability of epididymis/testis palpation.

Body temperature at the time of diagnosing was above normal in all cases.

After AEO diagnosis, initially we used empiric conservative treatment in all patients using analgesics and one of the following antibacterial drug regimes:

ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly in a single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 10-14 days;

ofloxacin 300 mg orally twice a day for 10-14 days;

levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 10-14 days.

In the cases of confirmed or suspected gonorrhea we used cephalosporin and doxycycline therapy because uncontrolled fluoroquinolone usage makes many strains of gonococci resistant to this group of drugs [1]. Bed rest, scrotal elevation, and analgesics were recommended until fever and local inflammation subsided.

If during the first 48-72 hours of conservative treatment there was no clinical improvement (body temperature was still high, pain was not reduced) patients underwent surgery – revision of testis, Bergmann operation. If an abscess was present we preformed surgical disclosure. In cases of purulent destruction we performed epididymectomy with resection of the epididymis or testis. If subtotal destruction of the involved testis occurred, patients underwent orchiectomy.

After completed treatment we have analyzed clinical outcomes in each group.

We also performed sexual partner notification and treatment for all patients with epididymo-orchitis secondary to gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and nongonococcal urethritis, or as indicated in undetermined etiology [2].

RESULTS

All patients from the first group were successfully treated with antibiotics. Body temperature decreased by the 2nd or 3rd day of treatment in all cases – none required surgery.

In the second group conservative treatment was effective in 70 (85.4%) pts. and the other 12 (14.6%) pts. without clinical improvement underwent organ-sparing surgery.

In the III-A subgroup conservative treatment was effective in 24 (53.3%) pts. In the other 21 (46.7%) pts. organ-sparing operations were performed after 48-72 hours of conservative treatment failure.

All 53 pts. from subgroup III-B did not demonstrate an objective response to antibacterial treatment during the first 48-72 hours so they underwent surgery. Among them, 32 pts. (60.4% of this subgroup) had abscesses that required surgical disclosure – Bergman operations. In 10 pts. (18.9% of this subgroup) epididymectomy was performed. In 11 cases (20.8% of this subgroup) orchiectomies were performed.

In all cases of swelling of the epididymis/testis due to abscesses, antibacterial treatment did not demonstrate efficacy and patients underwent surgery.

Based on clinical signs and described outcomes we developed the following classification table of AEO, which distributes patients with AEO into three grades and suggests a treatment approach (Table 1). This classification can also predict the efficacy of conservative treatment for AEO.

Table 1.

Staging of acute epididymo-orchitis and its treatment

| STAGE | Palpation | SUI | TREATMENT | Efficacy of conservative treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E/T | Malacia | Hydrocele | Abscess | |||

| I | + | – | – | No | Conservative | 100% |

| II | + | – | + | None, one, or a few abscesses up to 0.5 cm in greatest dimension each one | Conservative initially. Surgery after 48-72 hours of conservative treatment failure | 85.4% |

| IIIA | – | – | + | 53.3% | ||

| IIIB | – | + – * |

+ | One or more abscesses above 0.5 cm in greatest dimension each one | Surgery | 0% |

E/T: palpable differences between epididymis and testis: + present = palpation reveals both enlarged painful epididymis and normal or insignificantly enlarged testis; – absent = on palpation, the enlarged epididymis is not differentiated from the enlarged, painful testis; * malacia was absent only in cases of large hydrocele or inability to palpate the epididymis/testis. SUI: scrotal ultrasound investigation

In our opinion, elevated body temperature should not be considered as a criterion of severity in the processes in AEO because it was present in all cases. This is also why this index was not included in the table.

The presented data shows a high efficacy of conservative treatment in patients with stages I (100% pts. of this group) and II (85.4% pts. of this group) of AEO according to our classification. In 46.7% of patients with stage IIIA and in 100% of patients with stage IIIB of AEO, initial conservative treatment was not effective so the patients underwent surgery.

Approximately 1/3 of all our patients: 12 pts. (14.6% of this group) with stage II and 74 pts. (75.5% of this group) with stage III required surgical treatment – 88.5% of all operations were organ-sparing.

DISCUSSION

AEO is the most common cause of intrascrotal inflammation. Epididymitis, which commonly precedes AEO, is the fifth most common urologic diagnosis in men aged 18-50 years. In the United States, acute epididymitis accounts for more than 600,000 medical visits per year [1].

Both acute epididymitis and AEO can be a complication of lower urinary tract infections or chronic prostatitis caused by specific and/or non-specific pathogens. Melekos M.D. and Asbach H.W. have presented that in men younger than 40 years old, 56% of epididymitis cases were caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and 18% by other bacteria. Whereas in those older than 40 years, the incidence of epididymitis resulting from urinary tract infection bacteria was 68% and only 18% from C. trachomatis [3]. The similar proportion was noted by De Jong Z. et al. In a group of 12 patients older than 35 yrs., 10 pts. had gram-negative infection (83%), one patient had a gram-positive infection, and only one patient had C. trachomatis (8%) [4]. It is possible to summarize that generally patients with AOE under 35 years of age would most probably suffer from C. trachomatis infection. Gonorrhea and other sexually transmitted diseases (STD) with or without C. trachomatis presence may cause AEO in this group of patients too [1, 5, 6]. On the other hand, those over this age have a high chance of the presence of a bacterial infection, usually coliform. Whilst, a part of AEO cases are sometimes idiopathic [7].

Epididymo-orchitis accounts for 7-22% of all genitourinary tuberculosis cases and assumes a greater relative importance in high prevalence regions [8, 9]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis usually extends from prostate to epididymis through the vas deferens. It also rarely may be a result of hematogenic or lymphatic M. tuberculosis dissemination from prostate or bladder lesions, which in turn are secondary to renal lesions. [10, 11]. The higher frequency of isolated epididymal tuberculosis lesions in children favors the possibility of hematologic spread of infection, whereas adults seem to develop tuberculous epididymo-orchitis caused by direct spread of pathogen from the urinary tract [12].

Acute orchitis as a complication of mumps is registered in up to 40% of postpubertal males [13].

AEO may also occur after indwelling urethral catheter as well as transurethral diagnostic and surgical manipulations [1, 14]. Epididymo-orchitis is more common in patients with spinal cord injury and clean intermittent catheterization than with indwelling urethral catheterization [(42.2% vs. 8.3%, P = 0.030)] [15].

Acute epididymitis may follow prostatic operations – an incidence of 13% was reported after suprapubic prostatectomy, with a higher risk in patients with preoperative urinary infections. Vasectomy at the time of operation reduced the risk of AEO development [16, 17].

Endoscopic operative procedures for posterior urethra obliteration in males may cause AEO in 4%. Open reconstructive-plastic operations on urethra – in 9.7% [18]. AEO also occurs because of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO). According to Hoeppner W. et al. (1992), in 336 men aged over 60 years presenting with acute epididymitis, lower urinary tract obstruction was identified in 187 (56%) pts., which was caused by benign prostate hyperplasia, prostate cancer, and/or urethral stricture [19].

Different urogenital malformations may also cause AEO. Congenital abnormalities have been associated with recurrent acute epididymitis [20, 21]. In young adults with acute epididymitis urological abnormalities are rarely present; they were noted in just 21 (3.4%) of 610 patients in the series of Mittemeyer B.T. et al. (1966), and included urethral strictures, hypospadias, neurogenic bladder, and hydronephrosis [14]. Urethro-ejaculatory duct reflux has been implicated as an important factor in the cause of acute epididymitis in children as well as in adults [17, 22].

Nonablative minimally invasive thermal therapies in the treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia lead to AEO in 2.0% of cases [23]. Intravesical treatment for superficial bladder tumors may cause AEO in 0.3% [24]. Men who engage in anal intercourse without condoms use are at risk of epididymitis secondary to sexually transmitted enteric organisms [25]. Non-infective epididymo-orchitis develops in 12-19% of men with the rare the Behcet's disease [26].

Patients with conditions that predispose to invasive candidal infections, e.g. diabetes or immunosuppression, may rarely develop a candidal epididymo-orchitis [27, 28, 29]. The drug amiodarone (Pacerone®, Cordarone®) used in the treatment of severe cases of irregular heart rhythms can also cause inflammation of the epididymis. It tends to resolve when amiodarone use is discontinued [30].

In endemic regions AEO may develop occasionally as a complication of brucellosis and systemic fungal infections such as blastomycosis [31, 32, 33].

Trauma to the scrotum can be a precipitating event of AEO especially if predisposing factors are present.

Classic palpation of the scrotum is the first method of diagnosing AEO. This technique allows establishing the anatomic structure of the scrotal organs, characteristics and grade of their inflammatory changes, differentiation between epididymis and testis, and their local softening (malacia) as a consequence of purulent destruction.

Scrotal ultrasound investigation is helpful in diagnosing AEO. This method makes it possible to evaluate the condition of the epididymis and testis – their structure and presence or absence and size of abscesses and hydrocele [34, 35]. Of high value in the differential diagnosis of AEO is color Doppler imaging of the scrotum. This method should be the study of choice to evaluate torsion of the spermatic cord as it demonstrates a high degree of accuracy. It also has proven to be quite helpful in evaluating the scrotal contents for the presence of inflammation and associated complications [36, 37].

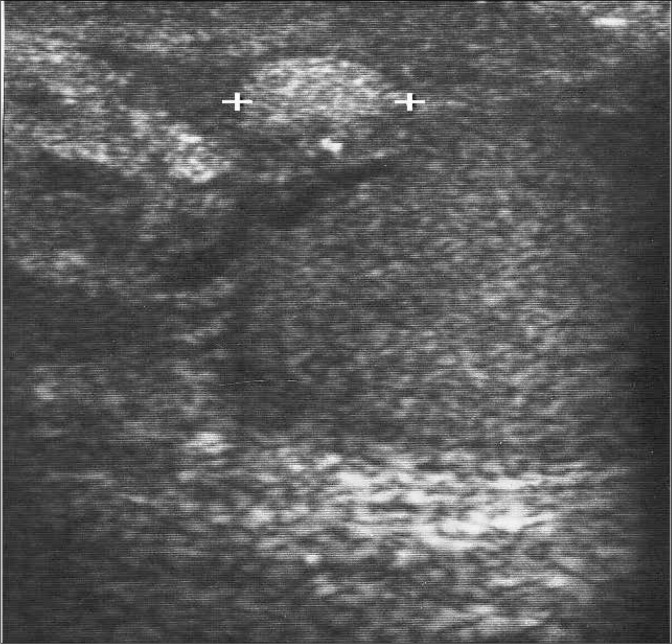

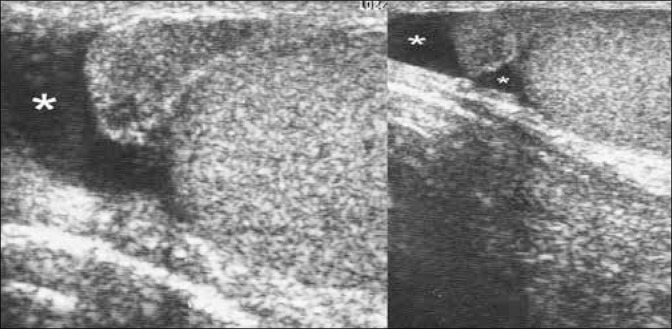

Acute inflammation in the epididymis and/or testis appears hypoechoic on ultrasound (Fig. 2), and color Doppler imaging shows increased blood flow. Abscesses are presented by enlargement of the epididymis and/or testis and affected areas appear to be hyperechoic (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

Abscess of epididymis (marked by red arrow) and hypoechoic areas in testis (marked by +).

Fig. 1.

Abscess of epididymis (hyperechoic, marked by +).

Common ultrasound pictures of acute epididymo-orchitis are presented on Figures 1–3.

Fig. 3.

Hydrocele (marked by *) and enlarged epididymis with hypoechoic area.

The treatment of AEO includes antibacterial drugs, analgesics, and, if necessary, surgery. Fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins have a similar effectiveness of 90% in antibiotic naive patients. However, fluoroquinolones with their efficacy against most sexually transmitted disease pathogens except Neisseria gonorrhea are suggested as first line therapy. Therefore, empiric antibiotic therapy as recommended in EAU guidelines is still adequate [38]. Also, compliance with contemporary guidelines in the treatment of AEO very often remains poor despite guidelines for the management of AEO raised by previous studies and efforts made to address them. The great variation in the management especially in patients from the over 50 y.o.a. subgroup suggests that a more systematic approach is required – a review in prostate assessment clinics would help [39, 40].

Taking into consideration the high probability of concomitant sexually transmitted diseases or chronic urethritis/prostatitis presence in patients with AEO aged <35 yrs., they and their sexual partners should be fully investigated to exclude any STD [5, 41].

In cases with the presence of urethral discharges, efforts should be undertaken to identify the etiologic agent.

Patients with AEO should be required to undergo standard urologic testing with digital rectal examination in order to evaluate the condition of the prostate and any possible comorbidities. In cases with the presence of BPH, STD, and/or urethritis/prostatitis, adequate therapy should be performed to exclude future AEO recurrence.

In everyday practice urologists often use the following conventional grading of AEO: mild, moderate, or grave severity of disease. Usually, the doctor has his own experience and vision of each stage of the disease and makes a subjective decision on the amount of therapy required. The indications to and timing of AEO surgical treatment are very important, but they are yet to be clearly defined – in which cases surgery should be performed immediately and when it is time to wait and treat AEO conservatively. Even now, some professionals advocate the active surgery approach in the treatment of AEO, and for others the conservative approach is predominantly preferential [40–44].

However, in patients with severe pathology accompanied by large abscess formation and swelling, the conservative treatment is not adequate in all cases because it leads to disease progression and may cause purulent destruction requiring orchiectomy. On the other hand, the wide use of surgery is not advisable in mild and moderate cases of AEO because medical therapy has a higher efficacy in such patients.

Our research of the literature did not reveal any guidelines for the staging of AEO depending on examination results that would let physicians determine the most appropriate treatment immediately after diagnosis. So, based on our own experience, we have presented a classification of AEO with staging and treatment options according to each stage of the disease. We hope that our classification will be helpful for urologists in choosing the best approach in the management of AEO.

CONCLUSIONS

In all AEO cases, initial body temperature is above normal and does not determine the treatment strategy. However, a decrease in body temperature in the first three days after commencing antibacterial treatment is a favorable prognostic sign.

Scrotal ultrasound investigation is an effective method of AEO diagnosis and staging.

Our classification facilitates systematic treatment approaches in patients with AEO.

AEO stages I-IIIA should be treated conservatively at fist. Surgery should be performed only in cases of conservative treatment failure during at least 2-3 days.

Stage IIIB is an indication to surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Management Guidelines 2006. MMWR. 2006;55(RR-11):61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horner PJ. European guideline for the management of epididymo-orchitis and syndromic management of acute scrotal swelling. Int J STD and AIDS. 2001;12(Suppl 3):88–93. doi: 10.1258/0956462011924010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melekos MD, Asbach HW. Epididymitis: Aspects concerning etiology and treatment. J Urol. 1987;138:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42999-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Jong Z, Pontonnier F, Plante P, et al. The frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis in acute epididymitis. Br J Urol. 1988;62:76–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb04271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger RE, Alexander ER, Monda GD, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis as a cause of acute “idiopathic” epididymitis. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:301–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197802092980603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes KK, Berger RE, Alexander ER. Acute epididymitis: Etiology and therapy. Andrology. 1979;3:309–316. doi: 10.3109/01485017908988421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger RE, Holmes KK, Mayo ME, et al. The clinical use of epididymal aspiration cultures in the management of selected patients with acute epididymitis. J Urol. 1980;124:60–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chattopadhyay A, Bhatnagar W, Agarwala S, et al. Genitourinary tuberculosis in pediatric surgical practice. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeve HR, Weinerth JL, Peterson LJ. Tuberculosis of epididymis and testicle presenting as hydrocele. Urology. 1974;4:329–331. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(74)90389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson WD, Jr, Johnson CW, Lowe FC. Tuberculosis and parasitic diseases of the genitourinary system. In: Walsh P.C, Retik A.B, Vaughan D.E Jr, Wein A.J, editors. Campbell's Urology. 8th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 743–795. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanagho EA, Kane CJ. Specific Infections of the genitourinary tract. In: Tanagho EA, McAninch J.W, editors. Smith's General Urology. 17th Edition. MC Graw Hill Medical; 2008. pp. 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madeb R, Marshall J, Nativ O, et al. Epididymal tuberculosis: case report and review of the literature. Urology. 2005;65(4):798. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beard CM, Benson RC, Jr, Kelalis PP, et al. The incidence of outcome of mumps orchitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935-1974. Mayo Clin Proc. 1977;52:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittemeyer BT, Lennox KW, Borski AA. Epididymitis: a review of 610 cases. J Urol. 1966;95:390–392. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ku JH, Jung TY, Lee JK, et al. Influence of bladder management on epididymo-orchitis in patients with spinal cord injury: clean intermittent catheterization is a risk factor for epididymo-orchitis. Spinal cord the official journal of the International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 2006;44(3):165–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck AD, Taylor DE. Post-prostatectomy epididymitis. A bacteriological and clinical study. J Urol. 1970;104:143–145. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61687-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinker JR, Hancock CV, Henderson WD. A statistical study of unilateral prophylactic vasectomy in the prevention of epididymitis 1029 cases. J Urol. 1970;104:303. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61724-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trapeznikova MF, Bazaev VV, Urenkov SB. Comparative analysis of open and endoscopic operative procedures outcomes for posterior urethra obliteration in males. Urologija. 2004;1:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeppner W, Strohmeyer T, Hartmann Lopez-Gamarra D, et al. Surgical treatment of acute epididymitis and its underlying diseases. Eur Urol. 1992;22:218–21. doi: 10.1159/000474759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weingartner K, Gerharz EW, Gillich M, et al. Ectopic third ureter causing recurrent acute epididymitis. Br J Urol. 1998;81:164–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegel A, Snyder H, Duckett JW. Epididymitis in infants and boys: Underlying urogenital anomalies and efficacy of imaging modalities. J Urol. 1987;138:1100–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Megalli M, Gursel E, Lattimer JK. Reflux of urine into ejaculatory ducts as a cause of recurring epididymitis in children. J Urol. 1972;108:978–979. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Ancona FCH. Nonablative minimally invasive thermal therapies in the treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18(1):21–27. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Georgescu DA, Geavlete P, Arabagiu I, Soroiu D. Complications of BCG intravesical treatment for superficial bladder tumours - 21 years’ follow-up. Eur Urol Suppl. 2006;5(2):189. Abstr 665. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes R, Daifuku R, Roddy R, et al. Urinary tract infections in sexually active homosexual men. Lancet. 1986;1:171–173. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho YH, Jung J, Lee KH, et al. Clinical features of patients with Behcet's disease and epididymitis. J Urol. 2003;170:1231–1233. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000081957.90395.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenks P, Brown J, Warnock D, et al. Candida glabrata epididymo-orchitis: an unusual infection rapidly cured. J Infect. 1995;31(1):71–72. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(95)91612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swartz DA, Harrington P, Wilcox R. Candidal epididymitis treated with ketoconazole. N Eng J Med. 1988;319:1485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Docimo SG, Rukstalis DB, Rukstalis MR, et al. Candida epididymitis: newly recognized opportunistic epididymal infection. Urology. 1993;41:280–282. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90576-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas A, Woodard C, Rovner ES, et al. Urologic complications of nonurologic medications. Urol Clin North Am. 2003;30(1):123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottesman JE. Coccidioidomycosis of prostate and epididymis with urethrocutaneous fistula. Urology. 1974;4:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(74)90384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Short KL, Harty JI, Amin M, et al. The use of ketoconazole to treat systemic blastomycosis presenting as acute epididymitis. J Urol. 1983;129:382–384. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibrahim AIA, Awad R, Shetty SD, et al. Genitourinary complications of brucellosis. Br J Urol. 1998;61:294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb13960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.See WA, Mack LA, Krieger JN. Scrotal ultrasonography: A predictor of complicated epididymitis requiring orchiectomy. J Urol. 1988;139:55–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mevorach RA, Lerner RM, Dvoretsky PM, et al. Testicular abscess: Diagnosis by ultrasonography. J Urol. 1986;136:1213–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Süzer O, Ozcan H, Küpeli S, et al. Color Doppler imaging in the diagnosis of the acute scrotum. Eur Urol. 1997;32:457–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herbener TE. Ultrasound in the assessment of the acute scrotum. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;24(8):405–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199610)24:8<405::AID-JCU2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilatz A, Wagenlehner F, Rusz A, et al. Empiric antibiotic therapy in acute epididymitis: Are guideline recommendations adequate? Eur Urol Suppl. 2012;11:e46. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Street E, Joyce A, Wilson J. 2010 United Kingdom national guideline for the management of epididymo-orchitis. Clinical Effectiveness Group, British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, 2010. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(7):361–365. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gujadhur R, Mohee A, Chang RTM, et al. Review of epididymoorchitis management in 3 UK centres: Are we still not doing enough? Eur Urol Suppl. 2012;11:e47. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Garbe C. Acute nongonococcal epididymitis. Aetiological and therapeutic aspects. Drugs. 1987;34(Suppl 1):111–117. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198700341-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaver I, Matzkin H, Braf ZF. Epididymo-orchitis: a retrospective study of 121 patients. J Fam Prac. 1990;30(5):548–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbuliev MG, Arbuliev KM, Gadzhiev DP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute epididymo-orchitis. Urologiia. 2008;3:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Epididymo-orchitis protocol. WOS MCN Clinical Guidelines Group. 2012. Apr, pp. 1–5. Available at: www.wossexualhealthmcn.org.