Abstract

Objectives

Although colonization traditionally is considered a risk factor for Staphylococcus aureus infection, the relationship between contemporary S. aureus colonization and infection is not well characterized. We aimed to relate colonizing and disease-causing strains of S. aureus within individuals and households.

Study design

In a prospective study in St. Louis, Missouri of 163 pediatric outpatients (cases) with community-associated S. aureus skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), infection isolates were obtained from cases along with colonization cultures from cases and their household contacts (n=562). Molecular typing by repetitive sequence-based PCR was employed to compare infecting and colonizing isolates within each case; the infecting strain from each case was compared with S. aureus strains colonizing household contacts. Colonization status of cases was followed for 12 months.

Results

Among 1299 S. aureus isolates evaluated, 27 distinct strain types were identified. The range of distinct strain types per household was 1-6. One hundred ten cases (67%) were colonized at ≥1 body site with their infecting strain. Of the 53 cases whose infecting strain did not match a colonizing strain, 15 (28%) had ≥1 household contact whose colonizing strain matched the case’s infecting strain. Intrafamilial strain-relatedness was observed in 105 (64%) families.

Conclusions

One-third of cases were colonized with a different strain-type than the strain causing their SSTI. For cases with discordant SSTI/colonizing isolates, less than one-third could be linked to the strain from another household contact, suggesting acquisition from sources external to the household.

Keywords: repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections are a significant public health problem [1-3], with skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) being the most common disease manifestation of community-associated (CA) MRSA [1, 4, 5]. Patients with S. aureus infections often are colonized with this organism [3, 6], but the relatedness of infecting and colonizing strains has not been well described in the community setting. Currently, many efforts to prevent recurrent SSTI focus on decolonization strategies in order to eradicate S. aureus carriage. However, if endogenous colonizing strains and disease-causing strains are discordant, decolonization measures may not be effective in preventing subsequent infections. Although nasal S. aureus isolates historically have been correlated with the strain subsequently isolated as the cause of healthcare-associated infections [7], Chen et al. recently demonstrated that only 59% of children with community-associated SSTI had wound isolates concordant with their colonizing isolates, suggesting that S. aureus infections do not always arise from endogenous sources [8].

CA-MRSA infections often cluster in households [9-12], with MRSA transmission occurring in as many as 40% of households of patients with MRSA infection or colonization [13]. Transmission dynamics within households may be explained by frequent close contact and potentially through contamination of fomites [14]. An evaluation of the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus could inform transmission dynamics and lead to evidence-based interventions to reduce the incidence of SSTI.

Recently we conducted a decolonization trial evaluating pediatric patients with S. aureus SSTI and colonization and measured the prevalence of S. aureus colonization among household contacts of these patients [15]. For the present study, we performed molecular typing by repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction (repPCR) to compare colonizing and disease-causing strains of S. aureus within index cases and among household contacts. Our objective was to determine whether index cases were infected with their endogenous colonizing strains and to determine strain similarity among household contacts to assess strain-relatedness of S. aureus within households.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office. Informed consent was obtained at study enrollment from index cases and their household contacts. Samples for the present study were obtained from a decolonization trial recently performed by our group which enrolled pediatric patients with community-associated SSTI [15]. This trial included patients (“index cases”) aged 6 months to 20 years who were cared for at St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH) emergency department (ED) and ambulatory wound center, and at nine community pediatric practices affiliated with a practice-based research network in metropolitan St. Louis from May 2008 to December 2009. Patients with risk factors for hospital-acquired S. aureus infections were excluded (those with an indwelling catheter, percutaneous medical device, or postoperative wound infection; undergoing dialysis; or residing in a long term care facility). For enrollment into the trial, patients were required to have a culture confirmed MRSA or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) SSTI, and be colonized in the anterior nares, axillae, or inguinal folds with S. aureus. The baseline colonization status of the anterior nares, axillae, and inguinal folds of household contacts of the index cases also was assessed as previously described. At enrollment, all index cases were prescribed decolonization with mupirocin and chlorhexidine for 5 days. Households were randomized to one of two groups: decolonization of the index case alone or decolonization of all household members [15]. The present study included 163 cases, each from a unique household, all of whom had an infecting isolate available for molecular typing and whose household contacts provided colonization swabs.

A standardized survey was administered to each index case at enrollment to collect demographic information about each case and household contacts. Characteristics of the home environment, such as household crowding, were assessed. Details about index case healthcare exposure and history of SSTI in the index case and household contacts were recorded.

Index cases were followed longitudinally for one year with follow-up visits 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after study enrollment. At follow-up, colonization status of index cases was assessed by repeat cultures of the anterior nares, axillae, and inguinal folds; a questionnaire was administered to assess incidence of SSTI in index cases and household contacts. Household contacts’ colonization status was measured only at baseline.

Microbiology and Molecular Typing

S. aureus isolates recovered from SSTI cultures were obtained from the SLCH microbiology laboratory or from the relevant pediatric practice. Colonization culture swabs (BBL Liquid Stuart; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) were processed as previously described [16, 17]. After overnight broth enrichment (BBL; Becton Dickinson), S. aureus isolates were recovered on sheep blood agar (BBL; Becton Dickinson) for further analyses. Isolates were classified as MRSA or MSSA using cefoxitin disk diffusion in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute criteria [18].

Molecular typing was performed on the index cases’ infecting and colonizing isolates at baseline and at the 4 follow-up visits (if subsequently colonized), and on colonizing isolates recovered from household contacts at baseline. RepPCR was performed as previously described [19, 20]. Isolates with a similarity index of ≥95% were considered to be identical. Each distinct strain was assigned a consecutive number as a reference strain; in addition to the numeric assignment, MRSA strains were given the designation “R” and MSSA strains were designated “S.” In addition to the standard phenotypic methods used to identify all S. aureus isolates in this study, the identity of the reference strains was confirmed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). MALDI-TOF MS analysis was performed using the Bruker Biotyper 3.0; isolates were analyzed in automatic mode using a Biotyper score of >2.0 for high-confidence identification [21].

Analysis of Strain Relatedness

Strain variability within index cases and household contacts at baseline and index cases at follow-up was assessed. Relatedness of infecting and colonizing strains within each index case was evaluated. The infecting strain from each index case also was compared with strains colonizing their household contacts. Intrafamilial strain-relatedness also was examined, defined as the presence of ≥ 1 household member carrying a S. aureus strain type identical to any other household member’s (including the index case) infecting or colonizing strain type at any time point throughout the study, as determined by repPCR pattern [12, 13].

Strain type relatedness also was compared between body site of colonization and site of infection. Infections in the face, scalp or neck were compared with colonization in the nose; infections in the chest, breast, trunk, axillae or upper extremity were compared with colonization in the axillae; and infections in the groin, labia, vulva, buttock or lower extremity were compared with colonization in the inguinal folds.

Statistical Analyses

Epidemiologic risk factors were compared between index cases with and without concordant colonizing and infecting isolates and between households with and without S. aureus intrafamilial strain-relatedness. Student t-test was used to analyze continuous variables and Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables using SPSS for Windows 20 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). Comparisons of age distributions between groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. All tests of significance were 2-tailed. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Index Patient and Household Contact Characteristics

The 163 cases had 562 household contacts enrolled in the study; the median household size was 4 people (range 2-12). The median age (range) of the cases was 2.8 (0.5-20) years. Seventy (44%) index cases experienced an SSTI in the year prior to study enrollment (Table I). The median age (range) of the 562 household contacts was 22.0 (0.1-88) years. Of 562 household contacts, 112 (21%) reported an SSTI in the year prior to study enrollment (Table I).

Table 1. Patient and Household Characteristics.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Index Cases | 163 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 2.8 (0.5-20) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 66 (40) |

| African-American | 97 (60) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 71 (44) |

| Female | 92 (56) |

| Number of persons in household, median (range) | 4 (2-12) |

| Household crowdinga | 27 (17) |

| SSTI in past year | 70 (44) |

| Any household contact with SSTI in past year | 90 (55) |

| Household Contacts | 562 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 22.0 (0.1-88) |

| Relationship to index case | |

| Parent | 247 (44) |

| Sibling | 211 (38) |

| Otherb | 104 (19) |

| SSTI in past yearc | 112 (21) |

>2 people per bedroom per household

Other household contact relationships include grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces, nephews, and friends

SSTI in past year was available for 538 household contacts

Baseline Colonization and SSTI

Of 163 index cases, 104 (64%) were colonized at the time of acute presentation (i.e., baseline) with MRSA only, 45 (28%) with MSSA only, and 14 (9%) with both MRSA and MSSA. MRSA was isolated from 132 (81%) index SSTI cultures, and MSSA was isolated from 31 (19%). Of 562 household contacts, 309 (55%) were colonized with S. aureus: 112 (20%) with MRSA only, 184 (33%) with MSSA only, and 13 (2%) with both MRSA and MSSA. Household contacts colonized with MRSA were more likely to have had an SSTI in the past year (36%) than those not colonized with MRSA (17%; p<0.001). The mean household colonization pressure (proportion of household contacts colonized) with S. aureus was 54%: 23% with MRSA and 33% with MSSA. Index cases colonized with S. aureus at 1, 2, and 3 anatomic sites at baseline had increasingly higher mean household S. aureus colonization pressures (48%, 58%, and 70%, respectively; p=0.011). Index cases colonized with S. aureus at 2 and 3 sites at baseline were more likely to be colonized with S. aureus during at least 1 longitudinal interval over the 12-month follow-up study than index cases colonized at just 1 site at baseline (95% and 93% vs. 77%, respectively; p=0.022).

Baseline Strain Variability within Cases and Households

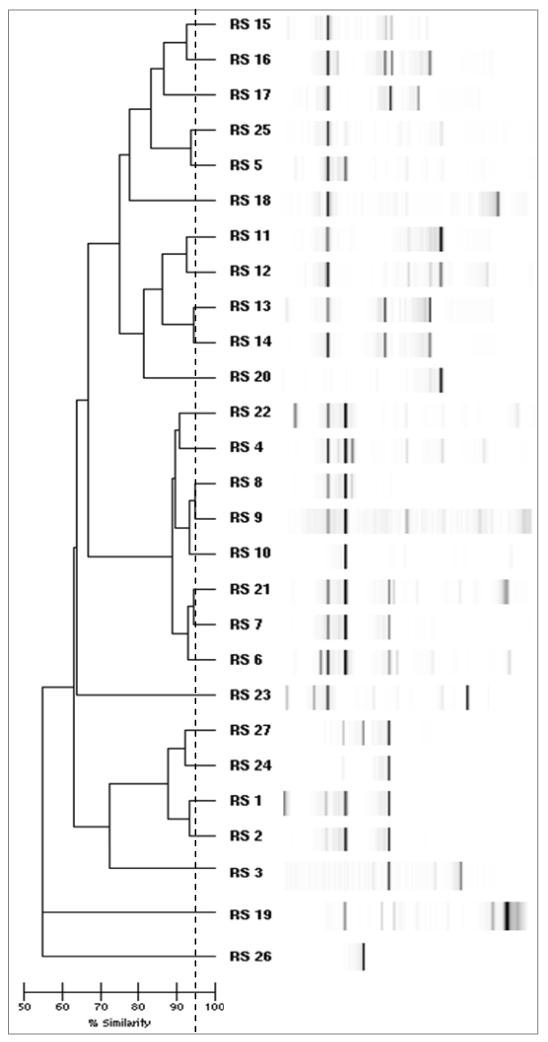

Among 1299 S. aureus isolates recovered from index cases (801 isolates) and household contacts (498 isolates), 27 distinct strain types were identified by repPCR (Figure 1). Two strain types (designated “2” and “24”) comprised 66% of the isolates. The predominant household S. aureus strain types, defined as the strain types recovered with the highest frequency within a particular household, were 2R in 55 households (34%) and 24R in 51 households (31%). Strain types 2R and 24R also were the most common infecting (2R 40%, 24R 33%) and colonizing (2R 34%, 24R 34%) strain types in index patients, and these predominated at each site of colonization (nares, axillae, and inguinal folds).

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of 27 distinct reference strains (RS). Dotted line demarcates the 95% similarity cutoff for determining distinct strain types.

At baseline, including both colonizing and infecting strains, 86 index cases (53%) carried 1 strain type, 71 cases (44%) carried 2 strain types, and 6 cases (4%) carried 3 strain types at different anatomic sites. The overall number of colonizing and infecting strain types per household (index case and household contacts) ranged between 1 and 6 at baseline. Of the 562 household contacts, 257 (46%) were colonized with 1 strain type and 52 (9%) carried multiple strain types at baseline (Table II).

Table 2. Strain Variability within Cases and Households.

| Number of Distinct Strain Types Detected |

Index Case at Baselinea N = 163 (%) |

Households at Baselineb N = 163 (%) |

Household Contacts at Baseline N = 562 (%) |

Index Case Longitudinallyc N = 163 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -d | -d | 253 (45) | -d |

| 1 | 86 (53) | 32 (20) | 257 (46) | 47 (29) |

| 2 | 71 (44) | 64 (39) | 51 (9) | 74 (45) |

| 3 | 6 (4) | 41 (25) | 1 (0.2) | 32 (20) |

| 4 | 0 | 23 (14) | 0 | 6 (4) |

| 5 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| 6 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

NOTE: percentages have been rounded to the nearest whole number

Includes infecting and colonizing isolates

Includes index cases and household contacts at baseline

Number of strain types carried by the index case over the 12 month longitudinal study

All index cases carried at least 1 strain for study eligibility

Strain Relatedness within Cases and Households

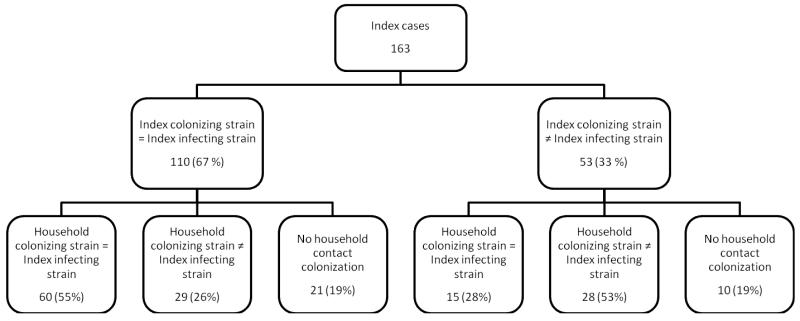

Of 163 index cases, 110 (67%) had at least 1 baseline colonizing strain that matched their infecting strain (Figure 2); 89 (55%) cases’ infecting strains matched all of their recovered colonizing strains. Index cases with concordant infecting and baseline colonizing strains were more likely to be African-American (66% vs. 45%, p=0.01) and have eczema (37% vs. 17%, p=0.01) than index cases with discordant infecting and baseline colonizing strains. The distribution of age (median [range]) across these two groups was similar (2.5 [0.5-20] years vs. 3.0 [0.6-18] years, p=0.98).

Figure 2.

Strain concordance of index case and household contacts colonizing and infecting strains.

Overall, 75 (46%) of 163 index cases had at least one household contact colonized with a strain concordant with their infecting strain, representing 23% (127 of 562) of all household contacts. Of 110 index cases with concordant colonizing and infecting strains, 60 (55%) had at least one household contact whose colonizing strain matched the index case’s infecting strain. Of 53 index cases whose infecting strain was not concordant with their colonizing strain, 15 (28%) had at least one household contact whose colonizing strain matched the index case’s infecting strain (Figure 2). At least one parent was colonized with S. aureus in 107 (66%) households; of these, 47 (44%) of the cases’ infecting strains matched a parent’s colonizing strain. Of 115 cases with siblings, 71 had at least one colonized sibling; 34 (48%) of these cases’ infecting strains matched their siblings’ colonizing strain.

Relationship between Infecting Strain and Colonizing Strain Recovered from an Adjacent Body Niche

Of 163 index cases, 109 (68%) were colonized at baseline at a body site proximate to the site of infection. Similar to the ratio of concordance between infecting and colonizing strains overall, in 74 (68%) of these cases, the adjacent body niche was colonized with a strain identical to the infecting strain. In evaluating specific sites of colonization, and 64% of cases with face, scalp or neck infections had concordant nasal colonization, and 65% of cases with groin, labia, vulva, buttock or lower extremity infections had concordant groin colonization, 87% of cases with chest, breast, trunk, axillae or upper extremity infections had concordant axillae colonization.

Longitudinal Strain Variability

Over the 12-month longitudinal study period (including the baseline sampling), index cases carried up to 6 distinct strain types (Table II). During this time, 118 (72%) index cases were colonized with at least 1 strain concordant with their baseline infecting strain. Additionally, after decolonization, 68 index cases acquired a coloning strain type not present at baseline. Of those acquiring a new strain type, 50 index cases (74%) acquired 1 different colonizing strain type, 13 (19%) acquired 2 different colonizing strain types, 4 (6%) acquired 3 different colonizing strain types, and 1 (1%) acquired 4 different colonizing strain types over 12 months. Of these 68 index cases acquiring a new strain type, 28 (41%) developed colonization with a new strain type that matched a baseline household contact colonizing strain.

Randomization to decolonization of the index case alone vs. the entire household did not affect index case longitudinal acquisition of a colonizing strain not present at baseline (38 of 81 [47%] vs. 30 of 82 [37%], respectively; p=0.21). Of index cases acquiring a new strain during follow-up, no differences were seen between treatment arms in the likelihood of the new strain matching a baseline household contact colonizing strain (15 of 38 [40%] in the index group vs. 13 of 30 [43%] in the household group, p=0.81).

Intrafamilial Strain-Relatedness

We documented occurrence of S. aureus intrafamilial strain-relatedness in 105 (64%) of 163 households. In households with intrafamilial strain-relatedness, the mean number (±SD) of household members was higher than in those without strain-relatedness (5.2±1.9 vs. 3.7±1.0, p<0.001). Households with intrafamilial strain-relatedness had both a higher mean MRSA colonization pressure (i.e., proportion of colonized household contacts, 0.34 ± 0.33 vs. 0.03 ± 0.11, p<0.001) and a higher mean MSSA colonization pressure (0.39 ± 0.34 vs. 0.23 ± 0.32, p=0.003) than households without strain-relatedness. Households with intrafamilial strain-relatedness were more likely to report SSTI in a household contact during the year prior to study enrollment than households without strain-relatedness (62 % vs. 43%, p=0.02); index case tended to have history of SSTI in the prior year (p=0.05). Age of index cases and household contacts was not significantly associated with S. aureus intrafamilial strain-relatedness (p=0.93 and 0.36, respectively). Additionally, intrafamilial strain-relatedness occurred in 57%, 69%, and 80% of households with index cases colonized with S. aureus at 1, 2, and 3 sites at baseline, respectively (p=0.07).

DISCUSSION

Historically, S. aureus colonization has been a demonstrated risk factor for subsequent infection [3, 6]. The present study determined that 67% of our pediatric patients were colonized at baseline with at least 1 strain that matched their infecting strain. The infecting strain from 55% of these index cases also was concordant with the colonizing strain from at least one household contact, suggesting that there may be unique characteristics regarding virulence and the potential for transmission of certain strain types. A striking 33% of cases, however, had discordant infecting and colonizing strains at baseline, even when strains were recovered from an adjacent body niche. Similar findings were demonstrated by Chen et al. who determined that only 59% of SSTI and nasal isolates in healthy children were concordant by both methicillin resistance status and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) type [8].

In the present study, intrafamilial strain-relatedness was identified in 64% of households, and 23% of household contacts overall were colonized with a strain type that matched the index cases’ infecting strain type. In households of patients with CA-MRSA infections in Hong Kong, 13% of household contacts were colonized or had infections with the same PFGE strain type [11]. In a cross-sectional study of patients with S. aureus SSTI and their household contacts in Chicago and Los Angeles, 14% of household members were colonized with a strain type concordant with the index cases’ infecting strain [23]. In these published studies, in which a lower proportion of household contacts were colonized with a strain concordant with that of the index patient in comparison to the present study, the majority of index patients were adults. We suspect that our higher proportion of household strain similarity may be influenced by our pediatric index population and the likelihood that children are in closer contact with each other and with older family members, affording greater opportunity for transmission. Indeed, nearly half of our cases’ infecting strains were concordant with their parents’ and siblings’ colonizing strains. Several risk factors for intrafamilial strain-relatedness were observed in our study, including crowding and higher MRSA and MSSA colonization pressure (ie, number of colonized contacts). Similarly, Mollema et al demonstrated that index cases who transmitted MRSA to their household contacts had on average more household contacts than those who did not have transmission [24]. Additionally, an investigation of nosocomial MRSA transmission by Merrer et al also demonstrated that increased colonization pressure was the only independent risk factor for MRSA transmission in the hospital setting [25].

Although intrafamilial strain-relatedness was common, in the present study we also found that household contacts are not the sole source of S. aureus acquisition. In our population, of the index cases whose colonizing strain was discordant from their SSTI strain type, less than one-third had a household contact whose colonizing strain matched the index case’s infecting strain. In addition, during the 12-month follow-up period, 42% of index cases acquired a colonization strain not present at baseline. Of the newly acquired strains, only one-third matched a baseline household contact colonizing strain. These findings are important in light of the perception that household contacts serve as reservoirs for S. aureus transmission [15], and suggest that S. aureus is acquired from sources both within and outside the household.

In the present study, 27 unique S. aureus repPCR strain types were detected in cases and their households. Within households, a diversity of strain types was present, with up to 6 different strain types recovered from individual households at baseline. Miller et al. demonstrated similar strain variability; of 350 households studied, 65% contained more than one S. aureus strain type [23]. In two U.S. studies comparing colonizing and infecting S. aureus strain types, strain types recovered from active infections differed from those recovered from sites of colonization. In the household study by Miller et al, 53% of infecting strains and only 29% of colonizing strains were characterized as PFGE type USA300 [23]. In a military study by Ellis et al, USA300 strains accounted for 97% of isolates recovered from abscesses, but only 53% of the colonizing isolates [26]. In contrast, in the present study, the most prevalent infecting strain types were also the most common colonizing strain types.

Our study has several limitations and strengths. Molecular typing was performed on a large collection of S. aureus isolates (almost 1300). The study population was part of an intervention trial that included a decolonization regimen performed after baseline sampling; this could have altered the colonizing flora during longitudinal samplings, potentially modulating the strain types associated with subsequent infections. Although throat cultures were not collected, we sampled three body sites that represent important niches for S. aureus colonization in children. Environmental samples also were not collected; fomites and pets may play a significant role in S. aureus transmission [14]. As colonization swabs were not collected from household contacts at longitudinal time points, we are unable to specify the directionality of S. aureus transmission within households. Lastly, although this study was conducted in a limited geographic area, our study population was diverse (with regard to race, patient age, and body sites of infection), and thus our results may be generalizable to other populations affected by CA-S. aureus.

In the epidemic of contemporary S. aureus infections, sources of infection other than endogenous colonization, including direct person-to-person and fomite-to-person transmission, as well as host and bacterial factors, are important in staphylococcal pathogenesis [14]. Although current efforts to prevent S. aureus SSTI focus on decolonization, findings from the present study suggest that personal decolonization exclusively may not be optimally effective in preventing recurrent infection [15]. Additionally, the common practice of attempted decolonization of all household members [22] may be a suboptimal long-term solution, as sources external to the household may drive acquisition of and infection with distinct strains [15]. As both endogenous S. aureus colonization and exogenous sources appear to play a key role in the development of staphylococcal infection, improved understanding of household transmission dynamics, including vectors facilitating entrance into the household, reservoirs of S. aureus in the home environment, and targets for intervention to interrupt transmission, will be critical in developing future strategies targeted at preventing S. aureus infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the thoughtful reviews of this manuscript provided by David Hunstad, MD (Professor of Pathology & Immunology at Washington University School of Medicine at the time of the study ; he is now Executive Director of Research and Development, North America, bioMerieux). We thank W. Michael Dunne, Jr., PhD and Rachel Collins (both at Washington University School of Medicine) for technical assistance and guidance with strain typing.

Supported by the Infectious Diseases Society of America/National Foundation for Infectious Diseases Pfizer Fellowship in Clinical Disease (to S.F.), the National Institutes of Health (UL1-RR024992, KL2RR024994, and K23-AI091690 to S.F.), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01-HS021736 to S.F.), and the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital (to S.F.]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, the National Institutes of Health, or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- (CA-MRSA)

community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- (MSSA)

methicillin-sensitive S. aureus

- (SSTI)

skin and soft tissue infection

- (repPCR)

repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction

- (MALDI-TOF MS)

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- (ED)

emergency department

- (SLCH)

St. Louis Children’s Hospital

- (PFGE)

pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:380–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp070747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285–92. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fritz SA, Epplin EK, Garbutt J, Storch GA. Skin infection in children colonized with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect. 2009;59:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kaplan SL, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE, Hammerman WA, Lamberth L, Versalovic J, et al. Three-year surveillance of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1785–91. doi: 10.1086/430312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, Peter MO, Gauduchon V, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1128–32. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ellis MW, Hospenthal DR, Dooley DP, Gray PJ, Murray CK. Natural history of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in soldiers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:971–9. doi: 10.1086/423965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G, Study Group Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:11–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen AE, Cantey JB, Carroll KC, Ross T, Speser S, Siberry GK. Discordance between Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization and skin infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:244–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818cb0c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jones TF, Creech CB, Erwin P, Baird SG, Woron AM, Schaffner W. Family outbreaks of invasive community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:e76–8. doi: 10.1086/503265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Huang YC, Ho CF, Chen CJ, Su LH, Lin TY. Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in household contacts of children with community-acquired diseases in Taiwan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:1066–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31813429e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ho PL, Cheung C, Mak GC, Tse CW, Ng TK, Cheung CH, et al. Molecular epidemiology and household transmission of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Hong Kong. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huijsdens XW, van Santen-Verheuvel MG, Spalburg E, Heck ME, Pluister GN, Eijkelkamp BA, et al. Multiple cases of familial transmission of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2994–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00846-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johansson PJ, Gustafsson EB, Ringberg H. High prevalence of MRSA in household contacts. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:764–8. doi: 10.1080/00365540701302501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miller LG, Diep BA. Colonization, Fomites, and Virulence: Rethinking the Pathogenesis of Community-Associated Methicillin-Retant Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1086/526773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, Eisenstein KA, Rodriguez M, Epplin EK, et al. Household Versus Individual Approaches to Eradication of Community-Associated Staphylococcus aureus in Children: A Randomized Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:743–51. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fritz S, Camins BC, Eisenstein KA, Fritz JM, Epplin EK, Burnham CA, Dukes J, Storch GA. Effectiveness of measures to eradicate Staphylococcus aureus in patients with community-associated skin and soft-tissue infections: a randomized trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:872–80. doi: 10.1086/661285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fritz SA, Garbutt J, Elward A, Shannon W, Storch GA. Prevalence of and risk factors for community-acquired methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children seen in a practice-based research network. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1090–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; twenty-third Informational supplement; M100-S23. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA: Jan, 2013. Update. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dunne WM, Maisch S. Epidemiological Investigation of Infections Due to Alcaligenes Species in Children and Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: Use of Repetitive-Element-Sequence Polymerase Chain Reaction. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:836–41. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Camins BC, Ainsworth AJ, Patrick C, Martin MS, et al. Mupirocin and Chlorhexidine Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus in Patients with Community-Onset Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:559–68. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01633-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tekippe EM, Shuey S, Winkler DW, Butler MA, Burnham CA. Optimizing Identification of Clinically Relevant Gram-positive Organisms Using the Bruker Biotyper MALDI-TOF MS System. J Clin Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02680-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Creech CB, Beekmann SE, Chen Y, Polgreen PM. Variability among pediatric infectious diseases specialists in the treatment and prevention of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:270–2. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815c9068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Miller LG, Eells SJ, Taylor AR, David MZ, Ortiz N, Zychowski D, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization among household contacts of patients with skin infections: risk factors, strain discordance, and complex ecology. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;54:1523–35. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mollema FPN. Transmission of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus to Household Contacts. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48:202–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01499-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Merrer J, Santoli F, Appere de Vecchi C, Tran B, De Jonghe B, Outin H. “Colonization pressure” and risk of acquisition of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a medical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:718–23. doi: 10.1086/501721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ellis MW, Griffith ME, Jorgensen JH, Hospenthal DR, Mende K, Patterson JE. Presence and molecular epidemiology of virulence factors in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing and infecting soldiers. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:940–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02352-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Clarridge JE, 3rd, Harrington AT, Roberts MC, Soge OO, Maquelin K. Impact of strain typing methods on assessment of relationship between paired nares and wound isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:224–31. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02423-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]