Abstract

Dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations (DyKAT) of racemic β-bromo-α-keto esters via direct aldolization of nitromethane and acetone provide access to fully substituted α-glycolic acid derivatives bearing a β-stereocenter. The aldol adducts are obtained in excellent yield with high relative and absolute stereocontrol under mild reaction conditions. Mechanistic studies determined that the reactions proceed through a facile catalyst-mediated racemization of the β-bromo-α-keto esters under a DyKAT Type I manifold.

Keywords: dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation (DyKAT), Henry reaction, acetone aldol, organocatalyzed, α-keto ester

Deracemization is a valuable method for the generation of chiral molecules from simple racemic starting materials.[1] While there are a plethora of reported dynamic kinetic processes, most are arguably either complexity-neutral transformations (hydrogenation, acylation, etc.) or generate a single chiral center. Dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations (DyKAT) that utilize a C–C bond forming step in the construction of multiple stereocenters are highly valuable synthetic strategies.[2] In this communication, we describe dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations of racemic β-bromo-α-keto esters via direct aldolization employing both nitromethane and acetone.[3]

Based on Noyori's pioneering work in the development of dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) of β-keto esters via Ru-catalyzed hydrogenation,[4] our group has recently disclosed a protocol for the Ru(II)-catalyzed dynamic kinetic reduction via asymmetric transfer hydrogenation (DKR-ATH) of β-stereogenic-α-keto esters affording secondary glycolic acid derivatives (Scheme 1, eq. a).[5] Our group's longstanding interest in the synthesis of complex fully substituted glycolates[6] prompted us to investigate reaction manifolds for the dynamic addition of carbon nucleophiles to β-stereogenic-α-keto esters to provide access to products of this type (eq. b). In order for a DyKAT to be realized, a catalyst must be identified that can effectively racemize the α-keto ester without promoting self-condensation while also activating the nucleophile and delivering it with high stereoselection into a hindered ketone. We postulated that the identity of the β-substituent of the α-keto ester would be important in promoting the desired reactivity due to its direct impact on both the β-C–H acidity and steric environment about the ketone. To this end, β-halo-α-keto esters were selected to investigate this potential reactivity profile due to their previous success in DKR reactions.[5b,7]

Scheme 1.

Development of a DyKAT of β-stereogenic-α-keto esters.

We commenced our investigation by exploring the Henry addition of nitromethane to β-bromo-α-keto ester 1 (Table 1). A number of methods have been reported for the Henry addition into pyruvates;[8] however, there is limited precedent for non-pyruvic alkyl α-keto esters and β-branched substrates.[9] Quinidine (I) was found to catalyze the nitroaldol addition of (±)-1a in quantitative yield with good diastereoselectivity albeit poor enantioselectivity (entry 1). Although bifunctional catalysts II and III only provided marginal improvements in enantioselectivity employing DCM (entries 2 and 3), a solvent screen revealed that III in methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) provided 2a in >20:1 dr and 92.5:7.5 er (entry 6). Catalyst modifications to the secondary alcohol led to the identification of o-toluoyl-substituted IV as the optimized catalyst structure (entry 7). Attempts to further enhance the selectivity through the addition of tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBABr)[7a] or lowering the reaction temperature to 0 °C provided no improvement (entries 8 and 9). Gratifyingly, the iPr ester (±)-1b provided 2b in 96:4 er as a single diastereomer when IV was employed in 2Me-THF (entry 11). Under these optimized reaction conditions employing the pseudo-enantiomeric catalyst V, ent-2b can be obtained in >20:1 dr and 87:13 er (entry 12).

Table 1.

Henry DyKAT Optimization[a]

| entry | 1 | cat | solvent | dr[b] | er[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | I | DCM | 13:1 | 62:38 |

| 2 | 1a | II | DCM | 12:1 | 72:28 |

| 3 | 1a | III | DCM | 11:1 | 80:20 |

| 4 | 1a | III | toluene | 16:1 | 80.5:19.5 |

| 5 | 1a | III | MeCN | >20:1 | 88:12 |

| 6 | 1a | III | MTBE | >20:1 | 92.5:7.5 |

| 7 | 1a | IV | MTBE | >20:1 | 93:7 |

| 8[d] | 1a | IV | MTBE | >20:1 | 93:7 |

| 9[e] | 1a | IV | MTBE | >20:1 | 93:7 |

| 10 | 1b | IV | MTBE | >20:1 | 92:8 |

| 11 | 1b | IV | 2Me-THF | >20:1 | 96:4 |

| 12 | 1b | V | 2Me-THF | >20:1 | 13:87 |

Reactions were performed on 0.20 mmol scale and proceeded to full conversion as adjudged by TLC.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of crude material.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

With TBABr (10 mol%) as an additive.

Reaction performed at 0 °C for 30 h.

During the course of our optimization of Henry conditions, we observed that L-proline (A) catalyzed the addition of acetone to (±)-1b, providing ent-3b in quantitative yield and 96:4 er albeit in low diastereoselectivity (Table 2, entry 1). Although related to the l-proline-catalyzed DKRs recently reported by Zhang on highly activated 2-oxo-3-aryl-succinates and α,γ-diketo esters,[10] we sought to develop a DyKAT on the less activated β-bromo-α-keto ester (±)-1b. A number of direct acetone aldolization reactions with α-keto esters have been reported employing a range of catalysts.[11,12] We chose to examine catalysts derived from the cinchona alkaloids based on their success in the Henry reaction (Table 1). Cinchonidine-derived primary amine catalyst B with p-nitrobenzoic acid (PNBA) as cocatalyst in acetone:dioxane (1:9) delivered ent-3b in good diastereo- and enantioselectivity (entry 2). An examination of other polar solvents did not provide satisfactory improvement (entries 3–5); however, reaction with B run neat in acetone provided ent-3b in 95.5:4.5 er as a single diastereomer (entry 6). Attempts to further increase the enantioselectivity employing either C or D proved ineffective (entries 7 and 8), but pseudo-enantiomeric E provided slight improvement delivering 3b quantitatively with 96:4 er as a single diastereomer (entry 9).

Table 2.

Acetone Aldol DyKAT Optimization[a]

| entry | cat | solvent | dr[b] | er[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1[d] | A | acetone | 2:1 | 4:96 |

| 2 | B | acetone:dioxane (1:9) | 14:1 | 12:88 |

| 3 | B | acetone:EtOAc (1:9) | 8:1 | 19.5:80.5 |

| 4 | B | acetone:MeCN (1:9) | 5:1 | 16:84 |

| 5 | B | acetone:DMF(1:9) | 9:1 | 9.5:90.5 |

| 6 | B | acetone | >20:1 | 4.5:95.5 |

| 7 | C | acetone | >20:1 | 10.5:89.5 |

| 8 | D | acetone | >20:1 | 14.5:85.5 |

| 9 | E | acetone | >20:1 | 96:4 |

Reactions were performed on 0.20 mmol scale and proceeded to full conversion as adjudged by TLC.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of crude material.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Reaction performed with A (20 mol%) in the absence of PNBA for 3 h.

With optimized reaction conditions in hand, we probed the scope of both the direct Henry and acetone aldolization DyKATs of β-bromo-α-keto esters (Table 3). In addition to phenyl (2b and 3b), the reactions were tolerant of both ortho- and para-substituted aryl groups at the γ-position providing aldol adducts 2b–2d and 3b–3d in high yield and selectivity. Heteroaryl (±)-1e also reacted efficiently under the reaction conditions cleanly providing 2e and 3e. A range of linear alkyl substrates underwent aldolization with no loss in selectivity providing 2g–2i and 3g–3i in similarly high efficiency suggesting that aromatic interactions between substrate and catalyst are not required for high levels of selectivity. The increased steric requirements of γ-branching resulted in low diastereoselection and moderate enantioselection in the formation of 2j and 3j. The absolute configuration of (2R,3R)-2b and (2R,3R)-3e was in each case determined by x-ray crystallography and the other products were assigned by analogy.[13]

Table 3.

Substrate Scope for DyKATs[a]

| 2b: X = NO2 97% yield >20:1 dr 96:4 er |

|

3b: X = Ac 95% yield >20:1 dr 96:4 er |

| 2c: X = NO2 97% yield >20:1 dr 92:8 er |

|

3c: X = Ac 95% yield >20:1 dr 95.5:4.5 er |

| 2d: X = NO2 98% yield >20:1 dr 95.5:4.5 er |

|

3d: X = Ac 97% yield >20:1 dr 96.5:3.5 er |

| 2e: X = NO2 98% yield >20:1 dr 96:4 er |

|

3e: X = Ac 93% yield >20:1 dr 96:4 er |

| 2f: X = NO2 92% yield >20:1 dr 94.5:5.5 er |

|

3f: X = Ac 96% yield >20:1 dr 95.5:4.5 er |

| 2g: X = NO2 95% yield >20:1 dr 94:6 er |

|

3g: X = Ac 96% yield >20:1 dr 95.5:4.5 er |

| 2h: X = NO2 96% yield 17:1 dr 93:7 er |

|

3h: X = Ac 94% yield >20:1 dr 95.5:4.5 er |

| 2i: X = NO2 98% yield >20:1 dr 94.5:5.5 er |

|

3i: X = Ac 95% yield >20:1 dr 96:4 er |

| 2j:[b] X = NO2 95% yield 5:1 dr 87:13 er |

|

3j: X = Ac 90% yield 2.5:1 dr 90:10 er |

Reactions were performed on 0.20 mmol scale. Yield of isolated product reported. Diastereomeric ratio (dr) determined by 1H NMR analysis of crude material. Enantiomeric ratio (er) determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Reaction performed for 42 h.

Given that catalysts IV and E are derived from cinchona alkaloids, their pseudo-enantiomeric catalysts V and B are readily available and provide access to both enantiomeric series of Henry and acetone aldolization adducts. Although V provides ent-2b in only 87:13 er, a single recrystallization provides enantioenrichment to 99:1 er. The utility of these reactions is highlighted not only by the mild, operationally simple reaction conditions, but by the near quantitative yield of products obtained following a simple filtration of the crude reaction mixtures through a plug of silica gel obviating the need for aqueous workup.

In order to better understand the mechanistic nuances of the DyKAT, we sought to elucidate the racemization pathway of this reaction. During the development of an “interrupted” Feist–Bénary reaction, Calter proposed that the reaction of 1,3-diketones with β-bromo-α-keto esters proceeds via DKR, where halide SN2 displacement is promoted by TBABr or TBAI (Scheme 3a).[7] Since our reactions do not generate stoichiometric bromide and addition of TBABr provided no improvement (Scheme 3b), we sought to examine the nature of our dynamic system by studying the Henry reaction as a representative system.

Scheme 3.

Dynamic kinetic resolution via halide SN2 displacement.

We began our studies by monitoring the enantiomeric compositions of both starting material and product during the course of the reaction of (R)-1b.[14] While substrate racemization is obligatory to successful dynamic kinetic resolutions and certain DyKAT subtypes, this assay is seldom performed.[2e, 15] This experiment confirmed that the product, (2R,3R)-2b, is obtained in uniform selectivity and that starting material remains racemic throughout the entire course of the reaction. Notably, (R)-1b is racemized in less than 30 min to (±)-1b in the presence of IV, highlighting the configurational lability of β-bromo-α-keto esters under general base catalysis (Scheme 4a). Conducting the catalyzed Henry addition with CD3NO2 resulted in a primary kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD = 2.8) and only 36% D incorporation at the β-position (Scheme 4b).[16] These data suggest that racemization is at least partially an intimate ion process with protonation from the ammonium salt (protonated catalyst) rather than nitromethane, and generation of the reactive nitronate species contributes to the overall reaction rate. In situ monitoring of the reaction by No-D 1H NMR spectroscopy[17] in 2-MeTHF revealed no intermediates, confirming that the catalyst resting state is the neutral amine and corroborating that nitronate formation is an uphill process.

Scheme 4.

Racemization and deuterium labeling studies.

Since racemization of 1b is catalyst-mediated via a chiral onium enolate, the Henry addition is proceeding through a DyKAT.[1c] The moderate deuterium incorporation excludes a DyKAT Type II mechanism wherein the chiral onium enolate would directly participate in an ene-type reaction with aci-nitromethane.[18] Calter employed a pyrimidinyl-bridged bis(quinidine) catalyst in their “interrupted” Feist–Bénary reaction to overcome poor selectivities observed with quinidine itself suggesting that both chiral amines may be involved in the enantio-determining step. Non-linear effects have been sparingly studied with cinchona-derived catalysts.[19] To elucidate if a non-linear effect was observed in our Henry reaction, we employed a mixture of pseudo-enantiomeric catalysts IV and V. The Henry reaction was found to exhibit a linear relationship between catalyst diastereomeric composition and reaction enantioselectivity (R2 = 0.997), eliminating the possibility of a dimeric catalyst species with concomitant activation of electrophile and nucleophile (Figure 1). Based on these collective data, we propose that the reaction proceeds through a DyKAT Type I manifold (Scheme 5).[20]

Figure 1.

Evaluation of nonlinear effects in catalyzed Henry reactions.

Scheme 5.

Proposed DyKAT mechanism.

In conclusion, dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations of β-bromo-α-keto esters have been developed employing direct aldolization of nitromethane and acetone. The fully substituted β-bromo-α-glycolic acid derivatives are obtained with high levels of diastereo- and enantioselectivity in near quantitative yield. The operationally simple protocols offer rapid generation of molecular complexity through formation of vicinal stereocenters in a single C–C bond forming event. Mechanistic studies provide evidence for a DyKAT Type I manifold in the Henry addition of nitromethane into β-bromo-α-keto esters. Extensions of this work and discovery of new dynamic reaction manifolds employing α-labile carbonyls is of ongoing interest in our laboratory.

Experimental Section

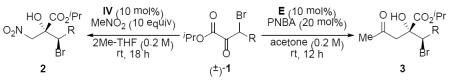

Henry aldol

A 1 dram vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with β-bromo-α-keto ester 1b (59.8 mg, 0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and MeNO2 (110 μL, 2.00 mmol, 10.0 equiv) in 2Me-THF (1.0 mL, 0.2 M). Catalyst IV (8.6 mg, 0.02 mmol, 0.1 equiv) was added, the vial was capped, and the reaction was allowed to stir for 18 h at room temperature. The reaction was filtered through a 2 cm pad of SiO2 washing with Et2O (5 × 2 mL) and concentrated in vacuo to afford analytically pure 2b (69.9 mg, 97% yield, >20:1 dr) as a white solid (mp: 113–116 °C).

Acetone aldol

A 1 dram vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with β-bromo-α-keto ester 1b (59.8 mg, 0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in acetone (1.0 mL, 0.2 M). Catalyst E (5.9 mg, 0.02 mmol, 0.1 equiv) and PNBA (6.7 mg, 0.04 mmol, 0.2 equiv) were added, the vial was capped, and the reaction was allowed to stir for 12 h at room temperature. The reaction was filtered through a 2 cm pad of SiO2 washing with Et2O (5 × 2 mL) and concentrated in vacuo to afford analytically pure 3b (67.9 mg, 95% yield, >20:1 dr) as a white solid (mp: 103–105 °C).

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Access to both enantiomeric series.

Acknowledgments

** The project described was supported by Award No. R01 GM084927 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. M.T.C. acknowledges the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of Chemistry for an Ernest L. Eliel Graduate Fellowship. X-ray crystallography performed by Dr. Peter S. White.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1].a) Huerta FF, Minidis ABE, Bäckvall J-E. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001;30:321–331. [Google Scholar]; b) Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:8291–8327. [Google Scholar]; c) Steinreiber J, Faber K, Griengl H. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:8060–8072. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:1563–1601. [Google Scholar]; e) Pellissier H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:659–676. [Google Scholar]; f) Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:3769–3802. [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Reyes E, Córdova A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:6605–6609. [Google Scholar]; b) Córdova A, Ibrahem I, Casas J, Sundén H, Engqvist M, Reyes E. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:4772–4784. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Parsons AT, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3122–3123. doi: 10.1021/ja809873u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhao G-L, Ullah F, Deiana L, Lin S, Zhang Q, Sun J, Ibrahem I, Dziedzic P, Córdova A. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:1585–1591. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Campbell MJ, Johnson JS, Parsons AT, Pohlhaus PD, Sanders SD. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:6317–6325. doi: 10.1021/jo1010735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Parsons AT, Smith AG, Neel AJ, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9688–9692. doi: 10.1021/ja1032277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].For a recent example of enantioconvergent aldolization of α-stereogenic aldehydes: Bergeron-Brlek M, Teoh T, Britton R. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3554–3557. doi: 10.1021/ol401370b.

- [4].a) Noyori R, Ikeda T, Ohkuma T, Widhalm M, Kitamura M, Takaya H, Akutagawa S, Sayo N, Saito T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:9134–9135. [Google Scholar]; b) Kitamura M, Tokunaga M, Noyori R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:144–152. [Google Scholar]; c) Noyori R, Tokunaga M, Kitamura M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1995;68:36–55. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Steward KM, Gentry EC, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7329–7332. doi: 10.1021/ja3027136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Steward KM, Corbett MT, Goodman CG, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:20197–20206. doi: 10.1021/ja3102709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Corbett MT, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:594–597. doi: 10.1021/ja310980q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Goodman CG, Do DT, Johnson JS. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2446–2449. doi: 10.1021/ol4009206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Nicewicz DA, Johnson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6170–6171. doi: 10.1021/ja043884l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boyce GR, Greszler SN, Johnson JS, Linghu X, Malinowski JT, Nicewicz DA, Satterfield AD, Schmitt DC, Steward KM. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:4503–4515. doi: 10.1021/jo300184h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Boyce GR, Liu S, Johnson JS. Org. Lett. 2012;14:652–655. doi: 10.1021/ol2033527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Schmitt DC, Malow EJ, Johnson JS. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:3246–3251. doi: 10.1021/jo202679u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Corbett MT, Uraguchi D, Ooi T, Johnson JS. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:4763–4767. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:4685–4689. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Slade MC, Johnson JS. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013;9:166–172. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Calter MA, Phillips RM, Flaschenriem C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14566–14567. doi: 10.1021/ja055752d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Calter MA, Li N. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3686–3689. doi: 10.1021/ol201332u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Christensen C, Juhl K, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Commun. 2001:2222–2223. doi: 10.1039/b105929g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Christensen C, Juhl K, Hazell RG, Jørgensen KA. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:4875–4881. doi: 10.1021/jo025690z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lu S-F, Du D-M, Zhang S-W, Xu J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2004;15:3433–3441. [Google Scholar]; d) Du D-M, Lu S-F, Xu J. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3712–3715. doi: 10.1021/jo050097d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Choudary BM, Ranganath KVS, Pal U, Kantam ML, Sreedhar B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13167–13171. doi: 10.1021/ja0440248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Blay G, Hernández-Olmosa V, Pedro JR. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:468–476. doi: 10.1039/b716446g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Bulut A, Aslan A, Dogan Ö. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7373–7375. doi: 10.1021/jo8010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Uraguchi D, Ito T, Nakamura S, Sakaki S, Ooi T. Chem. Lett. 2009;38:1052–1053. [Google Scholar]; i) Xu H, Wolf C. Synlett. 2010:2765–2770. [Google Scholar]; j) Miyake GM, Iida H, Hu H-Y, Tang Z, Chen EY-X, Yashima E. J. Polym. Sci. A: Polym. Chem. 2011;49:5192–5198. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Li H, Wang B, Deng L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:732–733. doi: 10.1021/ja057237l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Qin B, Xiao, Liu X, Huang J, Wen Y, Feng X. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:9323–9328. doi: 10.1021/jo701898r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Wang Y, Shen Z, Li B, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. Chem. Commun. 2007:1284–1286. doi: 10.1039/b616382c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yang J, Wang T, Ding Z, Shen Z, Zhang Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:2208–2213. doi: 10.1039/b822127h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].For seminal catalytic, enantioselective Mukaiyama aldol additions to α-keto esters: Evans DA, Kozlowski MC, Burgey CS, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:7893–7894. Evans DA, MacMillan DWC, Campos KR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:10859–10860. Evans DA, Burgey CS, Kozlowski MC, Tregay SW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:686–699.

- [12].a) Tang Z, Cun L-F, Cui X, Mi A-Q, Jiang Y-Z, Gong L-Z. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1263–1266. doi: 10.1021/ol0529391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xu X-Y, Tang Z, Wang Y-Z, Luo S-W, Cun L-F, Gong L-Z. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:9905–9913. doi: 10.1021/jo701868t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu Q-Z, Wang X-L, Luo S-W, Zheng B-L, Qin D-B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:7434–7437. [Google Scholar]; d) Jiang Z, Lu Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:1884–1886. [Google Scholar]; e) Li P, Zhao J, Li F, Chan ASC, Kwong FY. Org. Lett. 2010;12:5616–5619. doi: 10.1021/ol102254q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kan S-S, Li J-Z, Ni C-Y, Liu Q-Z, Kang T-R. Molecules. 2011;16:3778–3786. doi: 10.3390/molecules16053778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Peng L, Wang L-L, Bai J-F, Jia L-N, Guo Y-L, Luo X-Y, Wang F-Y, Xu X-Y, Wang L-X. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:4774–4777. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05607g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Zhu X, Lin A, Fang L, Li W, Zhu C, Cheng Y. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:8281–8284. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Viózquez SF, Bañón-Caballero A, Guillena G, Nájera C, Gómez-Bengoa E. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:4029–4035. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25224d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].CCDC 951438 ((2R,3R)-2b) and 951439 ((2R,3R)-3e) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- [14].See the supporting information for experimental details and data.

- [15].Wegman MA, Hacking MAPJ, Rops J, Pereira P, van Rantwijk F, Sheldon RA. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1999;10:1739–1750. [Google Scholar]

- [16].The kinetic isotope effect was measured by comparison of initial rates from parallel experiments with CH3NO2 and CD3NO2. See the supporting information for further experimental details.

- [17].Hoye TR, Eklov BM, Ryba TD, Voloshin M, Yao LJ. Org. Lett. 2004;6:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol049979+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].The possibility of this mechanism was suggested to us by Professor T. Rovis (Colorado State University).

- [19].a) Huck W-R, Mallat T, Baiker A. Catal. Lett. 2003;87:241–247. [Google Scholar]; b) Huck W-R, Bürgi T, Mallat T, Baiker A. J. Catal. 2003;216:276–287. [Google Scholar]; c) Ma Z, Zaera F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16414–16415. doi: 10.1021/ja0659323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ogura Y, Akakura M, Sakakura A, Ishihara K. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:8457–8461. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8299–8303. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].A reviewer pointed out that it might be simpler to classify these reactions as dynamic kinetic resolutions. Admittedly, the differences in the present case are subtle. According to the Steinreiber definition (reference 1c), DyKAT reactions take place via interconverting diastereomeric complexes where rate differences might reasonably be expected (or possible) for conversion of the enantiomeric starting materials to the “locally achiral” intermediate. This requirement is often taken to mean that the chiral catalyst that mediates the productive asymmetric transformation also catalyzes substrate racemization, a scenario that is certainly operative in the present case. We presume that diastereomeric precomplexes form between the substrate and the bifunctional catalyst prior to proton transfer, in analogy to soft enolization.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.