Abstract

Study Design

Concurrent prospective randomized and observational cohort studies.

Objective

To assess the 8-year outcomes of surgery vs. non-operative care.

Summary of Background Data

Although randomized trials have demonstrated small short-term differences in favor of surgery, long-term outcomes comparing surgical to non-operative treatment remain controversial.

Methods

Surgical candidates with imaging-confirmed lumbar intervertebral disc herniation meeting SPORT eligibility criteria enrolled into prospective randomized (501 participants) and observational cohorts (743 participants) at 13 spine clinics in 11 US states. Interventions were standard open discectomy versus usual non-operative care. Main outcome measures were changes from baseline in the SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) and Physical Function (PF) scales and the modified Oswestry Disability Index (ODI - AAOS/Modems version) assessed at 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months, and annually thereafter.

Results

Advantages were seen for surgery in intent-to-treat analyses for the randomized cohort for all primary and secondary outcomes other than work status; however, with extensive non-adherence to treatment assignment (49% patients assigned to non-operative therapy receiving surgery versus 60% of patients assigned to surgery) these observed effects were relatively small and not statistically significant for primary outcomes (BP, PF, ODI). Importantly, the overall comparison of secondary outcomes was significantly greater with surgery in the intent-to-treat analysis (sciatica bothersomeness [p > 0.005], satisfaction with symptoms [p > 0.013], and self-rated improvement [p > 0.013]) in long-term follow-up. An as-treated analysis showed clinically meaningful surgical treatment effects for primary outcome measures (mean change Surgery vs. Non-operative; treatment effect; 95% CI): BP (45.3 vs. 34.4; 10.9; 7.7 to 14); PF (42.2 vs. 31.5; 10.6; 7.7 to 13.5) and ODI (−36.2 vs. −24.8; −11.2; −13.6 to −9.1).

Conclusion

Carefully selected patients who underwent surgery for a lumbar disc herniation achieved greater improvement than non-operatively treated patients; there was little to no degradation of outcomes in either group (operative and non-operative) from 4 to 8 years.

Keywords: SPORT, intervertebral disc herniation, surgery, non-operative care, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar discectomy for relief of sciatica in patients with intervertebral disc herniation (IDH) is a well-researched and common indication for spine surgery, yet rates of this surgery exhibit considerable geographic variation.1 Several randomized trials and large prospective cohorts have demonstrated that surgery provides faster pain relief and perceived recovery in patients with herniated disc.2–6 The effect of surgery on longer term outcomes remains less clear.

In a classic RCT evaluating surgery versus non-operative treatment for lumbar IDH, Weber et al. showed a greater improvement in the surgery group at 1 year that was statistically significant; there was also greater improvement for surgery at 4 years, although not statistically significant, but no apparent difference in outcomes at 10 years.2 However, a number of patients in the non-operative group eventually underwent surgery over that time, complicating the interpretation of the long-term results. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, a prospective observational cohort, found greater improvement at one year in the surgery group that narrowed over time, but remained significantly greater in the surgical group for sciatica bothersomeness, physical function, and satisfaction, but no different for work or disability outcomes.3 This paper reports 8-year results from the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) based on the continued follow-up of the herniated disc randomized and observational cohorts.

METHODS

Study Design

SPORT is a randomized trial with a concurrent observation cohort conducted in 11 US states at 13 medical centers with multidisciplinary spine practices. The human subjects committees at each participating institution approved a standardized protocol for both the observational and the randomized cohorts. Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, study interventions, outcome measures, and follow-up procedures have been reported previously.5–8

Patient Population

Men and women were eligible if they had symptoms and confirmatory signs of lumbar radiculopathy persisting for at least six weeks, disc herniation at a corresponding level and side on imaging, and were considered surgical candidates. The content of pre-enrollment non-operative care was not pre-specified in the protocol. 5–7 Specific enrollment and exclusion criteria are reported elsewhere.6,7

A research nurse at each site identified potential participants, verified eligibility and used a shared decision making video for uniformity of enrollment. Participants were offered enrollment in either the randomized trial or the observational cohort. Enrollment began in March of 2000 and ended in November of 2004.

Study Interventions

The surgery was a standard open discectomy with examination of the involved nerve root.7,9 The non-operative protocol was “usual care” recommended to include at least: active physical therapy, education/counseling with home exercise instruction, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if tolerated. Non-operative treatments were individualized for each patient and tracked prospectively.5–8

Study Measures

Primary endpoints were the Bodily Pain (BP) and Physical Function (PF) scales of the SF-36 Health Survey10 and the AAOS/Modems version of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)11 as measured at 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months, and annually thereafter. If surgery was delayed beyond six weeks, additional follow-up data was obtained 6 weeks and 3 months post-operatively. Secondary outcomes included patient self-reported improvement; work status; satisfaction with current symptoms and care;12 and sciatica severity as measured by the sciatica bothersomeness index.13,14 Treatment effect was defined as the difference in the mean changes from baseline between the surgical and non-operative groups.

Statistical Considerations

Initial analyses compared means and proportions for baseline patient characteristics between the randomized and observational cohorts and between the initial treatment arms of the individual and combined cohorts. The extent of missing data and the percentage of patients undergoing surgery were calculated by treatment arm for each scheduled follow-up. Baseline predictors of time until surgical treatment (including treatment crossovers) in both cohorts were determined via a stepwise proportional hazards regression model with an inclusion criterion of p < 0.1 to enter and p > 0.05 to exit. Predictors of missing follow-up visits at yearly intervals up to 8 years were separately determined via stepwise logistic regression. Baseline characteristics that predicted surgery or a missed visit at any time-point were then entered into longitudinal models of primary outcomes. Those that remained significant in the longitudinal models of outcome were included as adjusting covariates in all subsequent longitudinal regression models to adjust for potential confounding due to treatment selection bias and missing data patterns. 15 In addition, baseline outcome, center, age and gender were included in all longitudinal outcome models.

Primary analyses compared surgical and non-operative treatments using changes from baseline at each follow-up, with a mixed effects longitudinal regression model including a random individual effect to account for correlation between repeated measurements within individuals. The randomized cohort was initially analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis.6 Because of cross-over, additional analyses were performed based on treatments actually received. In these as-treated analyses, the treatment indicator was a time-varying covariate, allowing for variable times of surgery. Follow-up times were measured from enrollment for the intent-to-treat analyses, whereas for the as-treated analysis the follow-up times were measured from the beginning of treatment (i.e. the time of surgery for the surgical group and the time of enrollment for the non-operative group), and baseline covariates were updated to the follow-up immediately preceding the time of surgery. This procedure has the effect of including all changes from baseline prior to surgery in the estimates of the non-operative treatment effect and all changes after surgery in the estimates of the surgical effect. The six-point sciatica scales and binary outcomes were analyzed via longitudinal models based on generalized estimating equations 16 with linear and logit link functions respectively, using the same intent-to-treat and adjusted as-treated analysis definitions as the primary outcomes. The randomized and observational cohorts were each analyzed to produce separate as-treated estimates of treatment effect. These results were compared using a Wald test to simultaneously test all follow-up visit times for differences in estimated treatment effects between the two cohorts.15 Final analyses combined the cohorts.

To evaluate the two treatment arms across all time-periods, the time-weighted average of the outcomes (area under the curve) for each treatment group was computed using the estimates at each time period from the longitudinal regression models and compared using a Wald test. 15

Kaplan-Meier estimates of re-operation rates at 8 years were computed for the randomized and observational cohorts and compared via the log-rank test. 17,18

Computations were done using SAS procedures PROC MIXED for continuous data and PROC GENMOD for binary and non-normal secondary outcomes (SAS version 9.1 Windows XP Pro, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 based on a two-sided hypothesis test with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons. Data for these analyses were collected through February 4, 2013.

RESULTS

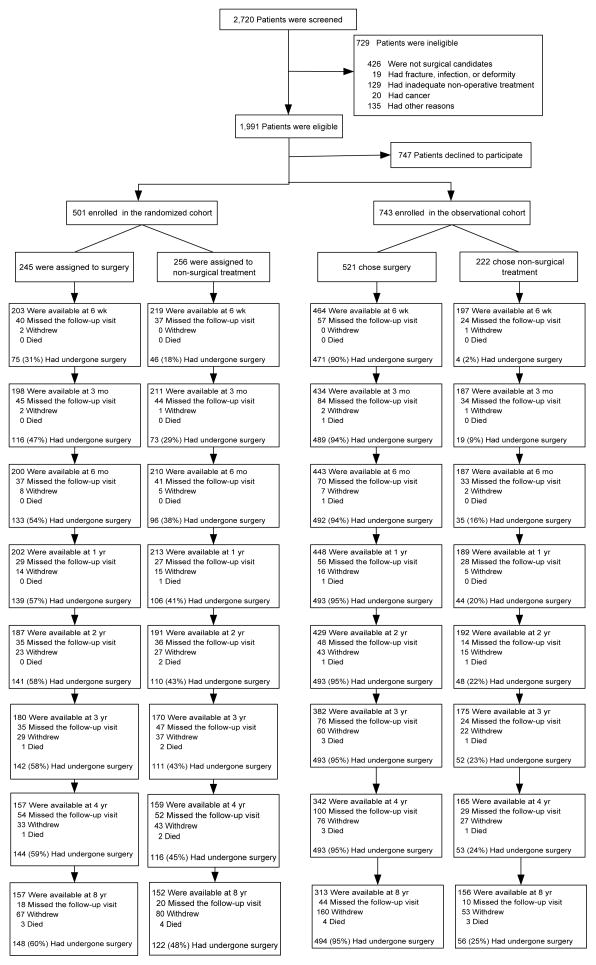

Overall, 1,244 SPORT participants with lumbar intervertebral disc herniation were enrolled (501 in the randomized cohort, and 743 in the observational cohort) (Figure 1). In the randomized cohort, 245 were assigned to surgical treatment and 256 to non-operative treatment. Of those randomized to surgery, 57% had surgery by 1 year and 60% by 8 years. In the group randomized to non-operative care, 41% of patients had surgery by 1 year and 48% by 8 years. In the observational cohort, 521 patients initially chose surgery and 222 patients initially chose non-operative care. Of those initially choosing surgery, 95% received surgery by 1 year; at 8 years 12 additional patients had undergone primary surgery. Of those choosing non-operative treatment, 20% had surgery by 1 year and 25% by 8 years. In both cohorts combined, 820 patients received surgery at some point during the first 8 years; 424 (34%) remained non-operative. Over the 8 years, 1,192 (96%) of the original enrollees completed at least 1 follow-up visit and were included in the analysis (randomized cohort: 94% and observational cohort 97%); 63% of initial enrollees supplied data at 8 years with losses due to dropouts, missed visits, or deaths (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Exclusion, Enrollment, Randomization and Follow-up of Trial Participants.

The values for surgery, withdrawal, and death are cumulative over 8 years. For example, a total of 1 patient in the group assigned to surgery died during the 4-year follow-up period. [Data set 04/10/2008]

Patient Characteristics

Baseline characteristics have been previously reported and are summarized in Table 1. 5,6,8 The combined cohorts had an overall mean age of 41.7 with slightly more men than women. Overall, the randomized and observational cohorts were similar. However, patients in the observational cohort had more baseline disability (higher ODI scores), were more likely to prefer surgery, more often rated their problem as worsening, and were slightly more likely to have a sensory deficit. Subjects receiving surgery over the course of the study were: younger; less likely to be working; more likely to report being on worker’s compensation; had more severe baseline pain and functional limitations; fewer joint and other co-morbidities; greater dissatisfaction with their symptoms; more often rated their condition as getting worse at enrollment; and were more likely to prefer surgery. Subjects receiving surgery were also more likely to have a positive straight leg test, as well as more frequent neurologic, sensory, and motor deficits. Radiographically, their herniations were more likely to be at the L4–5 and L5-S1 levels and to be posterolateral in location.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to study cohort and treatment received.

| IDH | SPORT Study Cohorts | p-value | Randomized and Observational Cohorts Combined: Treatment Received* | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Cohort | Observational Cohort | Surgery | Non-Operative | |||

| (n=474) | (n=721) | (n=803) | (n=392) | |||

| Mean Age (SD) | 42.3 (11.6) | 41.4 (11.2) | 0.18 | 40.7 (10.8) | 43.8 (12.3) | <0.001 |

| Female | 194 (41%) | 313 (43%) | 0.43 | 346 (43%) | 161 (41%) | 0.55 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic † | 450 (95%) | 690 (96%) | 0.63 | 766 (95%) | 374 (95%) | 0.89 |

| Race – White † | 401 (85%) | 635 (88%) | 0.10 | 707 (88%) | 329 (84%) | 0.061 |

| Education - At least some college | 357 (75%) | 530 (74%) | 0.53 | 583 (73%) | 304 (78%) | 0.077 |

| Income - Under $50,000 | 208 (44%) | 329 (46%) | 0.59 | 373 (46%) | 164 (42%) | 0.15 |

| Marital Status – Married | 333 (70%) | 504 (70%) | 0.95 | 562 (70%) | 275 (70%) | 0.99 |

| Work Status ‡ | 0.71 | 0.007 | ||||

| Full or part time | 292 (62%) | 433 (60%) | 467 (58%) | 258 (66%) | ||

| Disabled | 58 (12%) | 100 (14%) | 122 (15%) | 36 (9%) | ||

| Other | 124 (26%) | 187 (26%) | 213 (27%) | 98 (25%) | ||

| Compensation – Any | 76 (16%) | 132 (18%) | 0.35 | 162 (20%) | 46 (12%) | <0.001 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD) § | 28 (5.5) | 28 (5.6) | 0.88 | 28.2 (5.7) | 27.5 (5.3) | 0.064 |

| Smoker | 108 (23%) | 175 (24%) | 0.60 | 201 (25%) | 82 (21%) | 0.13 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Depression | 62 (13%) | 79 (11%) | 0.31 | 94 (12%) | 47 (12%) | 0.96 |

| Joint Problem | 98 (21%) | 124 (17%) | 0.15 | 130 (16%) | 92 (23%) | 0.003 |

| Other ¶ | 221 (47%) | 305 (42%) | 0.16 | 334 (42%) | 192 (49%) | 0.019 |

| Time since recent episode < 6 months | 374 (79%) | 559 (78%) | 0.62 | 619 (77%) | 314 (80%) | 0.27 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score || | 28.3 (19.9) | 26.4 (20.3) | 0.13 | 23.4 (18) | 34.8 (22.1) | <0.001 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score || | 39.5 (25.3) | 36.7 (25.7) | 0.066 | 32.6 (23.5) | 48.4 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score | 45.9 (12) | 44.7 (11.2) | 0.081 | 44.7 (11.4) | 46.2 (11.8) | 0.035 |

| Oswestry (ODI) ** | 46.9 (20.9) | 51.1 (21.4) | <0.001 | 54.7 (19.6) | 38.6 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| Sciatica Frequency Index (0–24) †† | 15.6 (5.5) | 16.1 (5.3) | 0.19 | 16.7 (5.1) | 14.2 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Sciatica Bothersome Index (0–24) ‡‡ | 15.2 (5.2) | 15.8 (5.3) | 0.057 | 16.4 (4.9) | 13.8 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 371 (78%) | 585 (81%) | 0.25 | 705 (88%) | 251 (64%) | <0.001 |

| Problem getting better or worse | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Getting better | 90 (19%) | 89 (12%) | 66 (8%) | 113 (29%) | ||

| Staying about the same | 221 (47%) | 315 (44%) | 348 (43%) | 188 (48%) | ||

| Getting worse | 162 (34%) | 311 (43%) | 383 (48%) | 90 (23%) | ||

| Treatment preference | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Preference for non-surg | 193 (41%) | 202 (28%) | 130 (16%) | 265 (68%) | ||

| Not sure | 154 (32%) | 43 (6%) | 114 (14%) | 83 (21%) | ||

| Preference for surgery | 127 (27%) | 473 (66%) | 556 (69%) | 44 (11%) | ||

| Pain Radiation | 459 (97%) | 706 (98%) | 0.33 | 787 (98%) | 378 (96%) | 0.15 |

| Straight Leg Raise Test - Ipsilateral | 291 (61%) | 460 (64%) | 0.43 | 520 (65%) | 231 (59%) | 0.058 |

| Straight Leg Raise Test - Contralateral/Both | 68 (14%) | 121 (17%) | 0.29 | 153 (19%) | 36 (9%) | <0.001 |

| Any Neurological Deficit | 352 (74%) | 552 (77%) | 0.40 | 625 (78%) | 279 (71%) | 0.014 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 203 (43%) | 279 (39%) | 0.17 | 330 (41%) | 152 (39%) | 0.48 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 223 (47%) | 382 (53%) | 0.051 | 433 (54%) | 172 (44%) | 0.001 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 191 (40%) | 311 (43%) | 0.36 | 359 (45%) | 143 (36%) | 0.008 |

| Herniation Level | 0.10 | <0.001 | ||||

| L2–L3 / L3–L4 | 32 (7%) | 56 (8%) | 42 (5%) | 46 (12%) | ||

| L4–L5 | 166 (35%) | 291 (40%) | 314 (39%) | 143 (36%) | ||

| L5–S1 | 275 (58%) | 374 (52%) | 446 (56%) | 203 (52%) | ||

| Herniation Type | 0.86 | 0.49 | ||||

| Protruding | 126 (27%) | 196 (27%) | 210 (26%) | 112 (29%) | ||

| Extruded | 315 (66%) | 471 (65%) | 537 (67%) | 249 (64%) | ||

| Sequestered | 32 (7%) | 54 (7%) | 55 (7%) | 31 (8%) | ||

| Posterolateral herniation | 379 (80%) | 542 (75%) | 0.064 | 636 (79%) | 285 (73%) | 0.015 |

Patients in the two cohorts combined were classified according to whether they received surgical treatment or only nonsurgical treatment during the first 8 years of enrollment.

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other = problems related to stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis, cancer, fibromyalgia, CFS, PTSD, alcohol, drug dependence, heart, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, hypertension, migraine, anxiety, stomach or bowel.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Surgical Treatment and Complications

Overall surgical treatment and complications were similar between the two cohorts (Table 2). The average surgical time was slightly longer in the randomized cohort (80.5 minutes randomized vs. 74.9 minutes observational, p=0.049). The average blood loss was 75.3cc in the randomized cohort vs. 63.2cc in the observational, p=0.13. Only 6 patients total required intra-operative transfusions. There were no perioperative mortalities. The most common surgical complication was dural tear (combined 3% of cases). Re-operation occurred in a combined 11% of cases by 5 years, 12% by 6 years, 14% by 7 years, and 15% by 8 years post-surgery. The rates of reoperation were not significantly different between the randomized and observational cohorts. Eighty-seven of the 119 re-operations noted the type of re-operation; approximately 85% of these (74/87) were listed as recurrent herniations at the same level. One death occurred within 90 days post-surgery related to heart surgery at another institution; the death was judged to be unrelated and was reported to the Institutional Review Board and the Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Table 2.

Operative treatments, complications and events.

| IDH | Randomized Cohort* (n=262) | Observational Cohort* (n=548) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discectomy Level | |||

| L2–L3 | 3 (1%) | 12 (2%) | 0.47 |

| L3–L4 | 8 (3%) | 20 (4%) | 0.85 |

| L4–L5 | 102 (40%) | 217 (40%) | 0.94 |

| L5–S1 | 152 (59%) | 306 (56%) | 0.43 |

| Median time to surgery in months (95% CI)† | 7.4 (4.7, 42.3) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | <0.001 |

| Operation time, minutes (SD) | 80.5 (40.9) | 74.9 (35.4) | 0.049 |

| Blood loss, cc (SD) | 75.3 (110.9) | 63.2 (102.8) | 0.13 |

| Blood Replacement | |||

| Intraoperative replacement | 4 (2%) | 2 (0%) | 0.16 |

| Post-operative transfusion | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Length of stay (SD) | 1 (1.1) | 0.94 (0.9) | 0.20 |

| Post-operative mortality (death within 6 weeks of surgery) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Post-operative mortality (death within 3 months of surgery) † | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.72 |

| Intraoperative complications ‡ | |||

| Dural tear/ spinal fluid leak | 12 (5%) | 14 (3%) | 0.19 |

| Nerve root injury | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.82 |

| Other | 2 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 0.51 |

| None | 247 (94%) | 533 (97%) | 0.056 |

| Postoperative complications/events § | |||

| Nerve root injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.70 |

| Wound hematoma | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 0.40 |

| Wound infection | 4 (2%) | 14 (3%) | 0.52 |

| Other | 9 (4%) | 18 (3%) | 0.96 |

| None | 244 (95%) | 513 (94%) | 0.62 |

| Additional surgeries (1-year rate) ¶ | 11 (4%) | 37 (7%) | 0.13 |

| Additional surgeries (2-year rate) ¶ | 16 (6%) | 50 (9%) | 0.12 |

| Additional surgeries (3-year rate) ¶ | 20 (7%) | 53 (10%) | 0.29 |

| Additional surgeries (4-year rate) ¶ | 24 (9%) | 61 (11%) | 0.32 |

| Additional surgeries (5-year rate) ¶ | 25 (9%) | 65 (12%) | 0.27 |

| Additional surgeries (6-year rate) ¶ | 29 (11%) | 73 (13%) | 0.31 |

| Additional surgeries (7-year rate) ¶ | 33 (12%) | 79 (14%) | 0.40 |

| Additional surgeries (8-year rate) ¶ | 35 (13%) | 84 (15%) | 0.38 |

| Recurrent disc herniation | 17 (7%) | 57 (11%) | |

| Complication or Other | 9 (3%) | 21 (4%) | |

| New condition | 3 (1%) | 10 (2%) |

270 RCT and 550 OBS patients had surgery. Surgical information was available for 262 RCT patients and 548 observational patients.

Patient died after heart surgery at another hospital, the death was judged unrelated to spine surgery.

None of the following were reported: aspiration, operation at wrong level, vascular injury.

Any reported complications up to 8 weeks post operation. None of the following were reported: bone graft complication, CSF leak, paralysis, cauda equina injury, wound dehiscence, pseudarthrosis.

One-, two-, three-, four-, five-, six-, seven- and eight-year post-surgical re-operation rates are Kaplan Meier estimates and p-values are based on the log-rank test. Numbers and percentages are based on the first additional surgery if more than one additional surgery.

Cross-Over

Non-adherence to treatment assignment affected both treatment arms: patients chose to delay or decline surgery in the surgical arm and crossed over to surgery in the non-operative arm. (Figure 1) Statistically significant differences of patients crossing over to non-operative care within 8 years of enrollment were that they were older, had higher incomes, less dissatisfaction with their symptoms, more likely to have a disc herniation at an upper lumbar level, more likely to express a baseline preference for non-operative care, less likely to perceive their symptoms as getting worse at baseline, and had less baseline pain and disability (Table 3). Patients crossing over to surgery within 8 years were more dissatisfied with their symptoms at baseline; were more likely to perceive they were getting worse at baseline; more likely to express a baseline preference for surgery; and had worse baseline physical function and more self-rated disability.

Table 3.

Statistically significant predictors of adherence to treatment among RCT patients.

| Assigned to Surgery | Assigned to Non-operative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Received within 8 Years | p-value | Treatment Received within 8 Years | p-value | |||

| Surgery | Non-operative | Surgery | Non-operative | |||

| IDH | (n=146) | (n=87) | (n=119) | (n=122) | ||

| Mean Age (SD) | 40.2 (10.9) | 43.9 (13) | 0.023 | 42.4 (10.2) | 43.5 (12.4) | 0.45 |

| Income - Under $50,000 | 67 (46%) | 27 (31%) | 0.036 | 63 (53%) | 51 (42%) | 0.11 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 128 (88%) | 57 (66%) | <0.001 | 101 (85%) | 85 (70%) | 0.008 |

| Herniation Level | 0.005 | 0.17 | ||||

| L2–L3 / L3–L4 | 4 (3%) | 12 (14%) | 5 (4%) | 11 (9%) | ||

| L4–L5 | 54 (37%) | 27 (31%) | 47 (39%) | 38 (31%) | ||

| L5–S1 | 88 (60%) | 48 (55%) | 66 (55%) | 73 (60%) | ||

| Problem getting worse | 60 (41%) | 23 (26%) | 0.03 | 47 (39%) | 32 (26%) | 0.04 |

| Treatment Preference | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Preference for non-surg | 47 (32%) | 49 (56%) | 34 (29%) | 63 (52%) | ||

| Not sure | 49 (34%) | 30 (34%) | 37 (31%) | 38 (31%) | ||

| Preference for surgery | 50 (34%) | 8 (9%) | 48 (40%) | 21 (17%) | ||

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score * | 25.9 (18.9) | 32.6 (22.5) | 0.015 | 26.9 (19.1) | 29.3 (19.7) | 0.33 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score * | 36.6 (24.1) | 45 (25.4) | 0.012 | 34 (23.7) | 44.2 (26.6) | 0.002 |

| Oswestry (ODI) † | 50.8 (21.1) | 42 (20.8) | 0.002 | 51 (19.3) | 41.6 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Sciatica Frequency Index (0–24) ‡ | 16.2 (5.2) | 15.1 (6.1) | 0.15 | 16.4 (5.5) | 14.5 (5.4) | 0.009 |

| Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (0–24) § | 15.9 (4.8) | 14.7 (5.5) | 0.11 | 16 (5.1) | 14 (5.3) | 0.003 |

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Main Treatment effects

Intent-to-Treat Analysis

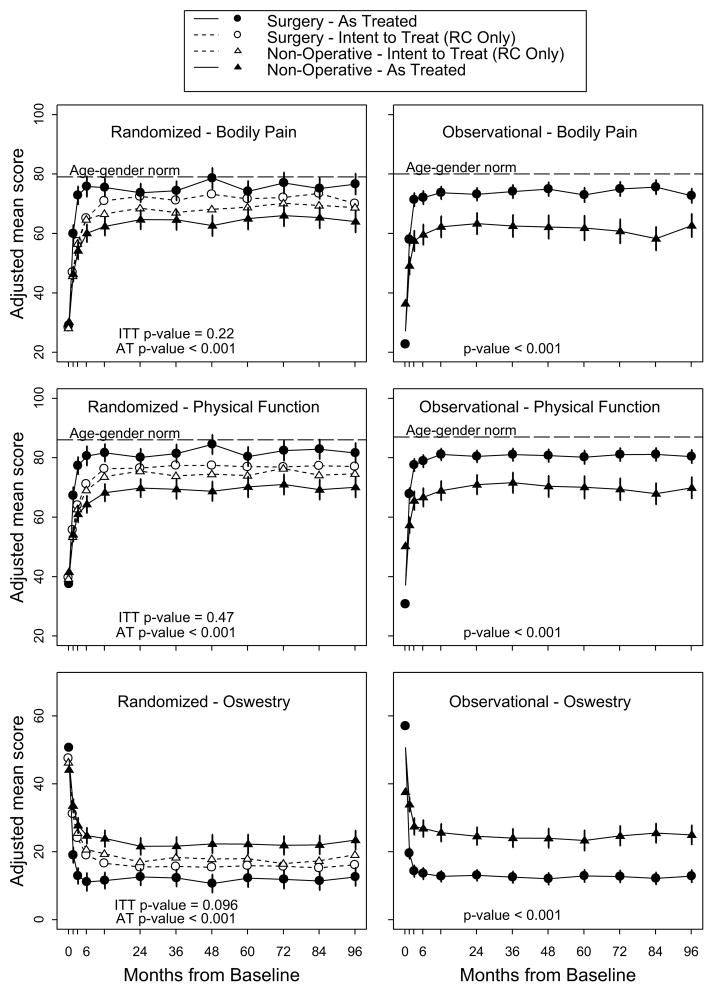

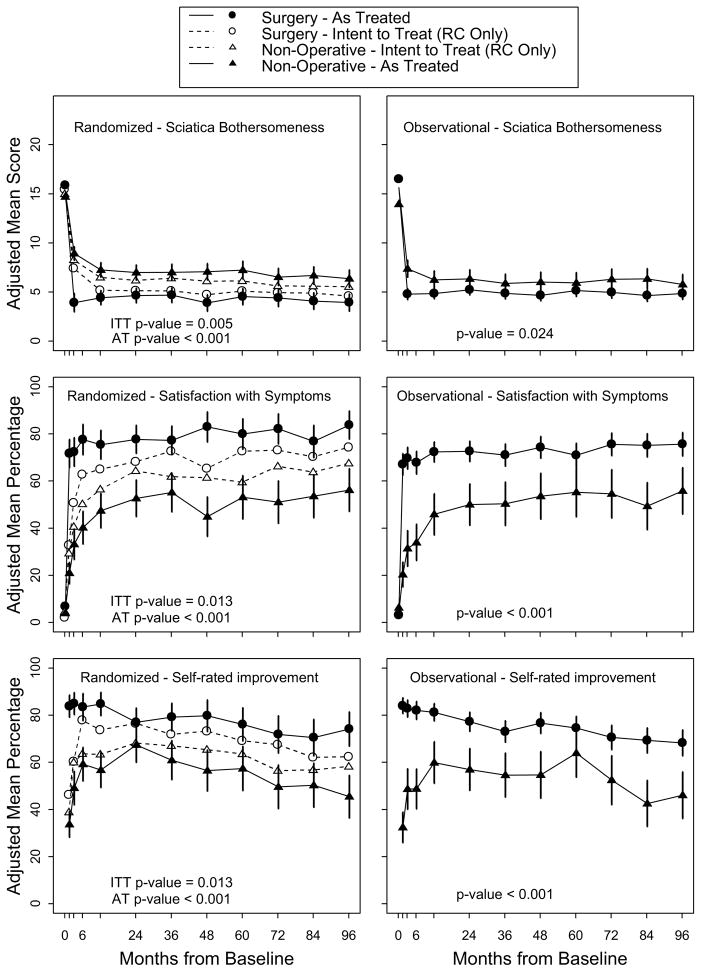

In the intention-to-treat analysis of the randomized cohort, all measures over 8 years favored surgery but there were no statistically significant treatment effects in the primary outcome measures (Table 4 and Figure 2). In the overall intention-to-treat comparison between the two treatment groups over time (area-under the curve), secondary outcomes were significantly greater with surgery in the intention-to-treat analysis (sciatica bothersomeness (p=0.005), satisfaction with symptoms (p=0.013), and self-rated improvement (p=0.013)) (Figure 3) Improvement in sciatica bothersomeness index was also statistically significant in favor of surgery at most individual time point comparisons (although non-significant in years 6 and 7) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Primary analysis results for years 1 to 8. Intent-to-treat for the randomized cohort and adjusted* analyses according to treatment received for the randomized and observational cohorts combined.†

| IDH | Baseline | 1-Year | 2-Year | 3-Year | 4-Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Overall Mean | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)† | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Surgery | Non-Operative | Surgery | Non-Operative | Surgery | Non-Operative | Surgery | Non-Operative | ||||||

| RCT Intent-to-treat | |||||||||||||

| Primary Outcomes | (n = 202) | (n = 213) | (n = 187) | (n = 191) | (n = 180) | (n = 170) | (n = 157) | (n = 159) | |||||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (0–100) (SE)‡ | 28.3 (0.92) | 42 (2) | 38.2 (2) | 3.8 (−1.7, 9.3) | 43.4 (2) | 39.8 (2) | 3.6 (−2, 9.2) | 42 (2.1) | 38.2 (2.1) | 3.8 (−2, 9.6) | 43.8 (2.2) | 39.5 (2.1) | 4.3 (−1.7, 10.2) |

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (0–100) (SE)‡ | 39.5 (1.2) | 36 (2) | 34.1 (1.9) | 1.9 (−3.5, 7.2) | 36.2 (2) | 35.8 (2) | 0.4 (−5.1, 5.9) | 36.9 (2) | 34.1 (2) | 2.9 (−2.7, 8.5) | 37.1 (2.1) | 34.7 (2.1) | 2.4 (−3.3, 8.2) |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (0–100) (SE)§ | 46.9 (0.96) | −30.4 (1.7) | −26.7 (1.6) | −3.7 (−8.3, 0.9) | −31.4 (1.7) | −28.7 (1.7) | −2.7 (−7.3, 2) | −31.2 (1.7) | −27.1 (1.7) | −4.1 (−8.8, 0.7) | v31.4 (1.8) | −27.7 (1.8) | −3.7 (−8.6, 1.2) |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||||||||

| Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (0–24) (SE)¶ | 15.2 (0.24) | −10.1 (0.46) | −8.3 (0.46) | −1.8 (−3.1, −0.5) | −10.1 (0.47) | −8.6 (0.47) | −1.5 (−2.8, −0.2) | −10.1 (0.48) | −8.3 (0.48) | −1.8 (−3.2, −0.5) | −10.5 (0.5) | −8.6 (0.49) | −1.9 (−3.3, −0.5) |

| Leg pain (0–6) (SE)|| | 4.6 (0.1) | −3.2 (0.2) | −2.8 (0.2) | −0.4 (−0.9, 0) | −3.3 (0.2) | −2.8 (0.2) | −0.5 (−0.9, 0) | −3.4 (0.2) | −2.7 (0.2) | −0.7 (−1.1, −0.2) | −3.5 (0.2) | −2.9 (0.2) | −0.6 (−1.1, −0.2) |

| Low back pain bothersomeness (0–6) (SE)** | 3.9 (0.1) | −1.7 (0.2) | −1.6 (0.2) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) | −1.9 (0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) | −1.9 (0.2) | −1.6 (0.2) | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) | −1.7 (0.2) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ symptoms (%) | 3.4 (1.8) |

64.9 | 56.4 | 8.5 (−1.3, 18.2) | 68.1 | 64.3 | 3.8 (−5.9, 13.5) | 72.6 | 61.8 | 10.7 (0.6, 20.9) | 65.3 | 61.4 | 3.9 (−7, 14.8) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ care(%) | 91 | 85.9 | 5.1 (−1.1, 11.4) | 86.9 | 84.4 | 2.5 (−4.8, 9.7) | 84.6 | 84.7 | −0.1 (−7.9, 7.7) | 89.8 | 81 | 8.8 (0.8, 16.8) | |

| Self-rated progress: major improvement (%) |

|

73.7 | 63.4 | 10.4 (1.1, 19.6) | 76.5 | 68.1 | 8.4 (−0.8, 17.5) | 71.8 | 66.9 | 4.9 (−5.1, 14.9) | 73.2 | 65.3 | 7.9 (−2.6, 18.3) |

| Work status: working (%) | 64.3 (4.8) | 75.9 | 76.9 | −1 (−9.2, 7.3) | 75.4 | 75.2 | 0.2 (−8.3, 8.8) | 71.2 | 74.1 | −2.9 (−12.1, 6.4) | 71.7 | 74.7 | −3 (−12.4, 6.5) |

|

| |||||||||||||

| RCT/OC As-treated | |||||||||||||

| Primary Outcomes | (n = 670) | (n = 376) | (n = 675) | (n = 344) | (n = 594) | (n = 317) | (n = 541) | (n = 287) | |||||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (0–100) (SE)‡ | 28.3 (0.6) | 45.8 (0.88) | 33.3 (1.2) | 12.5 (9.7, 15.2) | 45 (0.88) | 35.1 (1.2) | 10 (7.2, 12.8) | 45.7 (0.91) | 34.6 (1.3) | 11.1 (8.2, 14.1) | 47.5 (0.95) | 33.5 (1.3) | 14 (10.9, 17.1) |

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (0–100) (SE)‡ | 38.3 (0.7) | 42.8 (0.82) | 30.1 (1.1) | 12.7 (10.2, 15.2) | 42 (0.82) | 32 (1.1) | 10 (7.5, 12.6) | 42.7 (0.85) | 32.1 (1.2) | 10.6 (7.9, 13.3) | 43.1 (0.88) | 31.1 (1.2) | 12 (9.2, 14.8) |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (0–100) (SE)§ | 49.1 (0.6) | −36.5 (0.67) | −24.3 (0.87) | −12.3 (−14.3, −10.3 | −36.1 (0.67) | −25.9 (0.88) | −10.2 (−12.2, −8.2) | −36.5 (0.69) | −26.2 (0.93) | −10.4 (−12.5, −8.2) | −37.3 (0.71) | −25.9 (0.97) | −11.4 (−13.6, −9.2) |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||||||||

| Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (0–24) (SE)¶ | 15.5 (0.1) | −10.9 (0.21) | −8.4 (0.28) | −2.4 (−3.1, −1.7) | −10.5 (0.21) | −8.6 (0.29) | −2 (−2.7, −1.3) | −10.8 (0.22) | −8.8 (0.3) | −2 (−2.7, −1.3) | −11.1 (0.23) | −8.7 (0.32) | −2.5 (−3.2, −1.7) |

| Leg pain (0–6) (SE)|| | 4.7 (0) | −3.5 (0.1) | −2.7 (0.1) | −0.8 (−1, −0.5) | −3.4 (0.1) | −2.8 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.8, −0.4) | −3.5 (0.1) | −2.9 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.8, −0.4) | −3.6 (0.1) | −2.9 (0.1) | −0.8 (−1, −0.5) |

| Low back pain bothersomeness (0–6) (SE)** | 3.8 (0) | −2.1 (0.1) | −1.4 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.8, −0.4) | −2 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.7, −0.2) | −2.1 (0.1) | −1.5 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.8, −0.3) | −2.1 (0.1) | −1.5 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.8, −0.4) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ symptoms (%) | 4.6 (2.1) |

73.8 | 45.4 | 28.4 (21.9, 34.9) | 74.6 | 50 | 24.7 (18, 31.3) | 73.7 | 51.3 | 22.4 (15.4, 29.4) | 76.8 | 47.6 | 29.2 (22, 36.5) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ care(%) | 92.9 | 84.4 | 8.6 (4.1, 13) | 92 | 79.9 | 12.2 (7, 17.3) | 90 | 75 | 15 (9.1, 21) | 91.6 | 77.9 | 13.7 (7.7, 19.7) | |

| Self-rated progress: major improvement (%) |

|

82.2 | 57.2 | 25 (18.7, 31.3) | 77.3 | 61.7 | 15.6 (9.1, 22.1) | 75 | 57.2 | 17.8 (10.7, 24.8) | 77.7 | 54.9 | 22.8 (15.5, 30.2) |

| Work status: working (%) | 73.7 (4.4) | 85.4 | 83.7 | 1.7 (−3.3, 6.7) | 84.8 | 84.7 | 0.1 (−4.9, 5.2) | 83.7 | 79.2 | 4.5 (−1.6, 10.7) | 83.4 | 77.7 | 5.8 (−1, 12.6) |

| IDH | Baseline | 5-Year | 6-Year | 7-Year | 8-Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Overall Mean | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | Mean Change (SE) or percent | Treatment Effect (95% CI)‡ | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Surgery | Non-Operative | Surgery | Non-Operative | Surgery | Non-Operative | Surgery | Non-Operative | ||||||

| RCT Intent-to-treat | |||||||||||||

| Primary Outcomes | (n = 151) | (n = 152) | (n = 156) | (n = 153) | (n = 154) | (n = 148) | (n = 157) | (n = 151) | |||||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (0–100) (SE)§ | 28.3 (0.92) | 42.3 (2.2) | 39.7 (2.2) | 2.6 (−3.5, 8.7) | 42.7 (2.1) | 41.4 (2.1) | 1.2 (−4.7, 7.2) | 44.1 (2.1) | 41.1 (2.2) | 3 (−2.9, 9) | 40.9 (2.1) | 40.2 (2.1) | 0.7 (−5.2, 6.6) |

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (0–100) (SE)§ | 39.5 (1.2) | 36.4 (2.1) | 33.8 (2.1) | 2.7 (−3.2, 8.5) | 36.2 (2.1) | 36.8 (2.1) | −0.6 (−6.3, 5.1) | 36.4 (2.1) | 34.4 (2.1) | 2.1 (−3.7, 7.8) | 36.3 (2.1) | 34.7 (2.1) | 1.7 (−4, 7.4) |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (0–100) (SE)¶ | 46.9 (0.96) | −30.8 (1.8) | −27.4 (1.8) | −3.4 (−8.4, 1.6) | −31.1 (1.8) | −29 (1.8) | −2.2 (−7, 2.7) | −31.4 (1.7) | −28.2 (1.8) | −3.1 (−8, 1.7) | −30.6 (1.8) | −26.4 (1.7) | −4.2 (−9, 0.7) |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||||||||

| Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (0–24) (SE)|| | 15.2 (0.24) | −10.1 (0.5) | −8.5 (0.51) | −1.6 (−3, −0.2) | −10.2 (0.5) | −9 (0.5) | −1.2 (−2.6, 0.2) | −10.3 (0.5) | −9.1 (0.5) | −1.2 (−2.6, 0.2) | −10.8 (0.5) | −9.2 (0.5) | −1.5 (−2.9, −0.2) |

| Leg pain (0–6) (SE)** | 4.6 (0.1) | −3.3 (0.2) | −2.8 (0.2) | −0.5 (−1, −0.1) | −3.3 (0.2) | −3 (0.2) | −0.3 (−0.8, 0.1) | −3.4 (0.2) | −3 (0.2) | −0.3 (−0.8, 0.1) | −3.5 (0.2) | −3 (0.2) | −0.5 (−0.9, 0) |

| Low back pain bothersomeness (0–6) (SE) †† | 3.9 (0.1) | −1.9 (0.2) | −1.7 (0.2) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) | −1.9 (0.2) | −1.9 (0.2) | 0 (−0.4, 0.5) | −1.8 (0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) | 0 (−0.5, 0.4) | −1.9 (0.2) | −1.7 (0.2) | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.2) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ symptoms (%) | 3.4 (1.8) |

72.6 | 59.4 | 13.2 (2.2, 24.2) | 73 | 66.2 | 6.8 (−3.7, 17.4) | 70.2 | 63.7 | 6.5 (−4.3, 17.2) | 74.3 | 67.4 | 6.8 (−3.4, 17) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ care(%) | 83.1 | 82.9 | 0.2 (−8.8, 9.1) | 88.3 | 85.4 | 2.9 (−4.9, 10.7) | 86.2 | 83.6 | 2.6 (−5.7, 11) | 84.9 | 84.3 | 0.6 (−7.6, 8.8) | |

| Self-rated progress: major improvement (%) |

|

69.2 | 63.5 | 5.6 (−5.5, 16.8) | 67.5 | 56.4 | 11.1 (0, 22.2) | 62.1 | 56.7 | 5.4 (−6, 16.7) | 62.3 | 58.2 | 4.1 (−7, 15.3) |

| Work status: working (%) | 64.3 (4.8) | 77.5 | 73.8 | 3.7 (−5.7, 13.1) | 75.2 | 72.2 | 2.9 (−6.5, 12.4) | 74.3 | 75.5 | −1.2 (−10.5, 8.2) | 74.1 | 69.6 | 4.5 (−5.1, 14.1) |

|

| |||||||||||||

| RCT/OC As-treated | |||||||||||||

| Primary Outcomes | (n = 486) | (n = 258) | (n = 504) | (n = 263) | (n = 506) | (n = 263) | (n = 498) | (n = 259) | |||||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (0–100) (SE)§ | 28.3 (0.6) | 45 (0.99) | 34.6 (1.4) | 10.4 (7.2, 13.7) | 47.1 (0.98) | 34.6 (1.3) | 12.5 (9.3, 15.7) | 47.1 (0.98) | 33 (1.3) | 14.1 (11, 17.3) | 45.3 (0.99) | 34.4 (1.3) | 10.9 (7.7, 14) |

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (0–100) (SE)§ | 38.3 (0.7) | 41.8 (0.91) | 31.7 (1.3) | 10.1 (7.2, 13.1) | 42.8 (0.91) | 31.8 (1.2) | 10.9 (8, 13.9) | 43 (0.9) | 30.2 (1.2) | 12.8 (10, 15.7) | 42.2 (0.92) | 31.5 (1.2) | 10.6 (7.7, 13.5) |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (0–100) (SE)¶ | 49.1 (0.6) | −36.3 (0.74) | −26.2 (1) | −10.1 (−12.4, −7.8) | −36.4 (0.74) | −25.8 (0.99) | −10.7 (−13, −8.4) | −37 (0.73) | −25.3 (0.97) | −11.7 (−13.9, −9.4) | −36.2 (0.74) | −24.8 (0.97) | −11.3 (−13.6, −9.1) |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||||||||

| Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (0–24) (SE)|| | 15.5 (0.1) | −10.6 (0.24) | −8.6 (0.34) | −2 (−2.8, −1.2) | −10.8 (0.24) | −8.8 (0.33) | −1.9 (−2.7, −1.1) | −11.1 (0.24) | −8.7 (0.33) | −2.4 (−3.2, −1.6) | −11 (0.25) | −9.1 (0.33) | −1.8 (−2.6, −1) |

| Leg pain (0–6) (SE)** | 4.7 (0) | −3.4 (0.1) | −2.9 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.8, −0.2) | −3.5 (0.1) | −2.9 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.9, −0.4) | −3.6 (0.1) | −2.8 (0.1) | −0.8 (−1, −0.5) | −3.6 (0.1) | −2.9 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.9, −0.4) |

| Low back pain bothersomeness (0–6) (SE)†† | 3.8 (0) | −2.1 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.7, −0.2) | −2.1 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.8, −0.3) | −2.2 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.6 (−0.8, −0.3) | −2.1 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −0.5 (−0.7, −0.2) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ symptoms (%) | 4.6 (2.1) |

74 | 52.6 | 21.4 (13.6, 29.2) | 78 | 51.3 | 26.7 (19.1, 34.4) | 76.2 | 49.6 | 26.6 (19, 34.2) | 78.6 | 54.4 | 24.2 (16.6, 31.7) |

| Very/somewhat satisfied w/ care(%) | 92.3 | 74.6 | 17.6 (11, 24.3) | 92.2 | 75 | 17.2 (10.6, 23.7) | 91.7 | 76.1 | 15.6 (9.1, 22) | 91.7 | 72.6 | 19.1 (12.5, 25.8) | |

| Self-rated progress: major improvement (%) |

|

74.6 | 59.7 | 14.9 (7.1, 22.8) | 70.9 | 50.3 | 20.6 (12.6, 28.6) | 69.6 | 45.9 | 23.8 (15.9, 31.6) | 70.1 | 45.3 | 24.8 (16.9, 32.6) |

| Work status: working (%) | 73.7 (4.4) | 85.1 | 80.6 | 4.4 (−2.3, 11.1) | 84.5 | 80.7 | 3.8 (−2.8, 10.5) | 82.3 | 75.7 | 6.6 (−0.7, 13.9) | 78.3 | 74.9 | 3.3 (−4.3, 11) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, compensation, smoking status, herniation location, working status, stomach comorbidity, depression, diabetes, other*** comorbidity, self-rated health trend, duration of most recent episode, treatment preference, baseline score (for SF-36, ODI, and Sciatica Bothersomeness Index), and center.

The sample sizes for the as-treated analyses reflect the number of patients contributing to the estimate in a given time-period using the longitudinal modeling strategy explained in the methods section, and may not correspond to the counts provided for each visit time in Figure 1.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and non-operative mean change from baseline.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

The Sciatica Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

The Leg Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

The Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

Figure 2. Primary Outcomes (SF-36 Bodily Pain and Physical Function, and Oswestry Disability Index) in the Randomized and Observational Cohorts during 8 Years of Follow-up.

The graphs show both the intent-to-treat and the as-treated analyses for the randomized cohort (column on the left) and the as-treated analysis for the observation cohort (column on the right). The horizontal dashed line in each of the 4 SF-36 graphics represents normal values adjusted for age and sex. The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. At 0 months, the floating data points represent the observed baseline mean scores for each study group, whereas the data points on plot lines represent the estimated means from the the adjusted analyses.

Figure 3. Secondary Outcomes (Sciatica Bothersomeness, Satisfaction with Symptoms, and Self-rated Global Improvement) in the Randomized and Observational Cohorts during 8 Years of Follow-up.

The graphs show both the intent-to-treat and the as-treated analyses for the randomized cohort (column on the left) and the as-treated analysis for the observation cohort (column on the right). The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals. At 0 months, the floating data points represent the observed baseline mean scores for each study group, whereas the data points on plot lines represent the estimated means from the adjusted analyses.

As-Treated Analysis

The adjusted as-treated effects seen in the randomized and observational were similar. Accordingly, the cohorts were combined for the final analyses. Treatment effects for the primary outcomes in the combined as-treated analysis were clinically meaningful and statistically significant out to 8 years: SF-36 BP 10.9 p < 0.001 (95% CI 7.7 to 14); SF-36 PF 10.6 p<0.001 (95% CI 7.7 to 13.5); ODI −11.3 p<0.001 (95% CI −13.6 to −9.1) (Table 4). The footnote for Table 4 describes the adjusting covariates selected for the final model.

Results from the intent-to-treat and as-treated analyses of the two cohorts are compared in Figure 2. In the combined analysis, treatment effects were statistically significant in favor of surgery for all primary and secondary outcome measures (with the exception of work status which did not differ between treatment groups) at each time point (Table 4 and Figure 3).

Loss-to-Follow-up

At the 8-year follow-up, 63% of initial enrollees supplied data, with losses due to dropouts, missed visits, or deaths. Table 5 summarized the baseline characteristics of those lost to follow-up compared to those retained in the study at 8-years. Those who remained in the study at 8 years were - somewhat older; more likely to be female, white, college educated, and working at baseline; less likely to be disabled, receiving compensation, or a smoker; less symptomatic at baseline with somewhat less bodily pain, better physical function, less disability on the ODI, better mental health, and less sciatica bothersomeness. These differences were small but statistically significant. Table 6 summarizes the short-term outcomes during the first 2 years for those retained in the study at 8 years compared to those lost to follow-up. Those lost to follow-up had worse outcomes on average; however this was true in both the surgical and non-operative groups with non-significant differences in treatment effects. The long-term outcomes are therefore likely to be somewhat over-optimistic on average in both groups, but the comparison between surgical and non-operative outcomes appear likely to be un-biased despite the long-term loss to follow-up.

Table 5.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to patient follow-up status as of 02/01/2013 when the IDH8yr data were pulled.

| IDH | Patients currently in study | Patients lost to follow-up | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=816) | (n=379) | ||

| Mean Age (SD) | 42.2 (11.2) | 40.7 (11.7) | 0.039 |

| Female | 369 (45%) | 138 (36%) | 0.005 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic | 782 (96%) | 358 (94%) | 0.36 |

| Race – White† | 725 (89%) | 311 (82%) | 0.002 |

| Education - At least some college | 625 (77%) | 262 (69%) | 0.007 |

| Income - Under $50,000 | 367 (45%) | 170 (45%) | 0.98 |

| Marital Status - Married | 595 (73%) | 242 (64%) | 0.002 |

| Work Status | <0.001 | ||

| Full or part time | 536 (66%) | 189 (50%) | |

| Disabled | 73 (9%) | 85 (22%) | |

| Other | 207 (25%) | 104 (27%) | |

| Compensation – Any‡ | 115 (14%) | 93 (25%) | <0.001 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 27.8 (5.6) | 28.3 (5.5) | 0.16 |

| Smoker | 163 (20%) | 120 (32%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Depression | 89 (11%) | 52 (14%) | 0.19 |

| Joint Problem | 150 (18%) | 72 (19%) | 0.86 |

| Other¶ | 351 (43%) | 175 (46%) | 0.34 |

| Time since recent episode < 6 months | 645 (79%) | 288 (76%) | 0.27 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score|| | 28.1 (20.6) | 25.1 (19) | 0.015 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score|| | 38.8 (25.5) | 35.7 (25.5) | 0.052 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score|| | 46 (11.5) | 43.4 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| Oswestry (ODI)** | 48.4 (21) | 51.7 (21.9) | 0.011 |

| Sciatica Frequency Index (0–24)†† | 15.7 (5.4) | 16.3 (5.5) | 0.089 |

| Sciatica Bothersome Index (0–24)‡‡ | 15.3 (5.2) | 16.1 (5.3) | 0.022 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 658 (81%) | 298 (79%) | 0.47 |

| Problem getting better or worse | 0.092 | ||

| Getting better | 133 (16%) | 46 (12%) | |

| Staying about the same | 370 (45%) | 166 (44%) | |

| Getting worse | 310 (38%) | 163 (43%) | |

| Treatment preference | 0.57 | ||

| Preference for non-surg | 277 (34%) | 118 (31%) | |

| Not sure | 136 (17%) | 61 (16%) | |

| Preference for surgery | 402 (49%) | 198 (52%) | |

| Pain Radiation | 798 (98%) | 367 (97%) | 0.43 |

| Straight Leg Raise Test - Ipsilateral | 505 (62%) | 246 (65%) | 0.35 |

| Straight Leg Raise Test - Contralateral/Both | 136 (17%) | 53 (14%) | 0.27 |

| Any Neurological Deficit | 630 (77%) | 274 (72%) | 0.077 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 342 (42%) | 140 (37%) | 0.12 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 425 (52%) | 180 (47%) | 0.16 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 347 (43%) | 155 (41%) | 0.64 |

| Herniation Level | 0.43 | ||

| L2–L3 / L3–L4 | 65 (8%) | 23 (6%) | |

| L4–L5 | 314 (38%) | 143 (38%) | |

| L5–S1 | 436 (53%) | 213 (56%) | |

| Herniation Type | 0.61 | ||

| Protruding | 223 (27%) | 99 (26%) | |

| Extruded | 530 (65%) | 256 (68%) | |

| Sequestered | 62 (8%) | 24 (6%) | |

| Posterolateral herniation | 631 (77%) | 290 (77%) | 0.81 |

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other = problems related to stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis, cancer, fibromyalgia, CFS, PTSD, alcohol, drug dependence, heart, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, hypertension, migraine, anxiety, stomach or bowel.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Table 6.

Time-weighted average of treatment effects at 2 years (AUC) from adjusted* as-treated randomized and observational cohorts combined primary outcome analysis, according to treatment received and patient follow-up status.

| IDH | Patient follow-up status | Surgical | Non-operative | Treatment Effect† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (SE)†† | Currently in study | 43.8 (0.7) | 31.2 (0.9) | 12.6 (10.4, 14.8) |

| Lost to follow-up | 38.8 (1.2) | 27.4 (1.6) | 11.4 (7.7, 15.1) | |

|

| ||||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.036 | 0.55 | |

|

| ||||

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (SE)†† | Currently in study | 40.9 (0.7) | 28.1 (0.9) | 12.8 (10.8, 14.9) |

| Lost to follow-up | 37 (1.1) | 25 (1.5) | 12 (8.6, 15.4) | |

|

| ||||

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.071 | 0.65 | |

|

| ||||

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (SE)‡ | Currently in study | −35.7 (0.6) | −23.1 (0.7) | −12.7 (−14.3, −11) |

| Lost to follow-up | −31 (1) | −20.9 (1.3) | −10.1 (−13, −7.3) | |

|

| ||||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.11 | |

|

| ||||

| Sciatica Bothersomeness Index (SE)§ | Currently in study | −8.8 (0.2) | −6.6 (0.2) | −2.2 (−2.7, −1.6) |

| Lost to follow-up | −8.4 (0.3) | −5.5 (0.4) | −3 (−3.8, −2.1) | |

|

| ||||

| p-value | 0.24 | 0.004 | 0.10 | |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, compensation, smoking status, herniation location, working status, stomach comorbidity, depression, diabetes, other** comorbidity, self-rated health trend, duration of most recent episode, treatment preference, baseline score (for SF-36, ODI, and Sciatica Bothersomeness Index), and center.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and non-operative mean change from baseline.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Sciatica Bothersomeness index range from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

DISCUSSION

In patients with a herniated disc confirmed by imaging and leg symptoms persisting for at least 6 weeks, surgery was superior to non-operative treatment in relieving symptoms and improving function. In the as-treated analysis, the treatment effect for surgery was seen as early as 6 weeks, appeared to reach a maximum by 6 months and persisted over 8 years; it is notable that the non-operative group also improved significantly and this improvement persisted with little to no degradation of outcomes in either group (operative and non-operative) between 4 and 8 years. In the longitudinal intention-to-treat analysis, all the outcomes showed small advantages for surgery, but only the secondary outcomes of sciatica bothersomeness, satisfaction with symptoms, and self-rated improvement were statistically significant. The persistent small benefit in the surgery group over time has made the overall intention-to-treat comparison more statistically significant over time despite high levels of cross-over. The large effects seen in the as-treated analysis after adjustments for characteristics of the crossover patients suggest that the intent-to-treat analysis may underestimate the true effect of surgery since the mixing of treatments due to crossover can be expected to create a bias toward the null in the intent-to-treat analyses.4,19 Loss to follow-up among patients who were somewhat worse at baseline and with worse short-term outcomes probably leads to overly-optimistic estimated long-term outcomes in both surgery and non-operative groups but unbiased estimates of surgical treatment effects.

Comparisons to Other Studies

There are no other long-term randomized studies reporting the same primary outcome measures as SPORT. The results of SPORT primary outcomes at 2 years were quite similar to those of Peul et al but longer follow up for the Peul study is necessary for further comparison.4,20 In contrast to the Weber study, the differences in the outcomes in SPORT between treatment groups remained relatively constant between 1 and 8 years of follow-up. One of the factors in this difference may be the sensitivity of the outcome measures – for example, sciatica bothersomeness, which was significantly different out to 8 years in the intention-to-treat, may be a more sensitive marker of treatment success than the general outcome measure used by Weber et al. 2

The long-term results of SPORT are similar to the Maine Lumbar Spine Study (MLSS).21 The MLSS reported statistically significantly greater improvements at 10 years in sciatica bothersomeness for the surgery group (−11.9) compared to the nonsurgical groups (−5.8) with a treatment effect of −6.1 p=0.004; in SPORT the improvement in sciatica bothersomeness in the surgical group at 8 years was similar to the 10 year result in MLSS (−11) though the non-operative cohort in SPORT did better than their MLSS counterparts (−9.1) however the treatment effect in SPORT, while smaller, remained statistically significant (−1.5; p<0.001) due to the much larger sample size. Greater improvements in the non-operative cohorts between SPORT and MLSS may be related to differences in non-operative treatments over time, differences between the two cohorts since the MLSS and did not require imaging confirmation of IDH.

Over the 8 years there was little evidence of harm from either treatment. The 8-year rate of re-operation was 14.7%, which is lower than the 25% reported by MLSS at 10 years. 22

Limitations

Although our results are adjusted for characteristics of cross over patients and control for important baseline covariates, the as-treated analyses presented do not share the strong protection from confounding that exists for an intent-to-treat analysis.4–6 However, However, intent-to-treat analyses are known to be biased in the presence of noncompliance at the level observed in SPORT, and our adjusted as-treated analyses have been shown to produce accurate results under reasonable assumptions about the dependence of compliance on longitudinal outcomes.23 Another potential limitation is the heterogeneity, of the non-operative treatment interventions, as discussed in our prior papers.5,6,8 Finally, attrition in this long-term follow-up study meant that only 63% of initial enrollees supplied data at 8 years with losses due to dropouts, missed visits, or deaths; based on analyses at baseline and at short-term follow-up, this likely leads to somewhat overly-optimistic estimated long-term outcomes in both treatment groups but an unbiased estimation of surgical treatment effect.

Conclusions

In the intention-to-treat analysis, small, statistically insignificant surgical treatment effects were seen for the primary outcomes but statistically significant advantages for sciatica bothersomeness, satisfaction with symptoms, and self-rated improvement were seen out to 8 years despite high levels of treatment cross-over. The as-treated analysis combining the randomized and observational cohorts, which carefully controlled for potentially confounding baseline factors, showed significantly greater improvement in pain, function, satisfaction, and self-rated progress over 8 years compared to patients treated non-operatively. The non-operative group, however, also showed substantial improvements over time, with 54% reporting being satisfied with their symptoms and 73% satisfied with their care after 8 years.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U01-AR45444; P60-AR062799) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant funds were received in support of this work. Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: consultancy, grants, stocks.

This study is dedicated to the memories of Brieanna Weinstein and Harry Herkowitz, leaders in their own rights, who simply made the world a better place.

Footnotes

”Other comorbidities include: stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis, cancer, fibromyalgia, cfs, PTSD, alcohol, drug dependency, heart, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, hypertension, migraine, anxiety, stomach, bowel

References

- 1.Dartmouth Atlas Working Group. Dartmouth Atlas of Musculoskeletal Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation. A controlled, prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine. 1983;8:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Keller RB, et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part II. 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica. Spine. 1996;21:1777–86. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2245–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. Jama. 2006;296:2451–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. Jama. 2006;296:2441–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN, Tosteson AN, et al. Design of the Spine Patient outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2002;27:1361–72. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2789–800. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ed8f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delamarter R, McCullough J. Microdiscectomy & Microsurgical Laminotomies. In: Frymoyer J, editor. The Adult Spine: Principles and Practice. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, et al. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daltroy LH, Cats-Baril WL, Katz JN, et al. The North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment Instrument: reliability and validity tests. Spine. 1996;21:741–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Patient satisfaction with medical care for low-back pain. Spine. 1986;11:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Patrick DL, et al. The Quebec Task Force classification for Spinal Disorders and the severity, treatment, and outcomes of sciatica and lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21:2885–92. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199612150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899–908. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. discussion 909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Philadelphia, PA: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically Efficient Rank Invariant Test Procedures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series a-General. 1972;135:185. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meinert CL. Clinical Trials: Design, Conduct, and Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peul WC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, et al. Prolonged conservative care versus early surgery in patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2008;336:1355–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Chang Y, et al. Surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: five-year outcomes from the Maine Lumbar Spine Study. Spine. 2001;26:1179–87. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, et al. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine. 2005;30:927–35. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158954.68522.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sitlani CM, Heagerty PJ, Blood EA, et al. Longitudinal structural mixed models for the analysis of surgical trials with noncompliance. Statistics in medicine. 2012;31:1738–60. doi: 10.1002/sim.4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]