Age at diagnosis is an important determinant of outcome among patients with multiple myeloma (MM). The median age at diagnosis is 70 years in the United States, which is similar to that in the United Kingdom (73 years) and Sweden (70 years).1–3 The subgroup over the age of 75 years represents a population in which the natural history of the disease and outcomes are not well studied.4–7 In one report, the median survival was less than 6 months in patients greater than 75 years of age, and hemoglobin and age were significant predictors of survival.4 Rodon et al.6 reported a median survival of 22 months in patients >75 years of age. Poor performance and elevated creatinine were adverse prognostic factors in this study. However, the majority of patients received melphalan or cyclophosphamide with prednisone and represent the era before introduction of the novel agents. The IFM01/01 trial8 enrolled patients over 75 years and showed a prolongation of survival with modest toxicity with melphalan, prednisone and thalidomide. We performed the current study to better define the outcome among patients over 75 years, who were seen at the Mayo Clinic between 1 January 1999 and 31 December 2008. The treatment responses were estimated according to the Uniform Response Criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group.9 The survival of MM patients aged ≤75 years in the same period was also reviewed for comparison. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

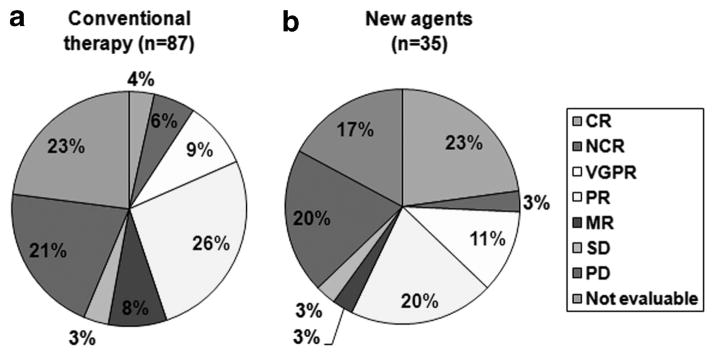

Two hundred and twelve patients >75 years of age with symptomatic MM were diagnosed during the study period. Among them, 73 patients (34%) with inadequate follow-up were excluded and the remaining 139 patients (66%) constitute the current study. Their median age was 80 years (range: 76–94) and 57% were male. During the same 10-year period, 1290 patients aged ≤75 years were seen. Their median age was 62 years (range: 23–75) and 79 (54%) were male. Among the 139 study patients, 20 (14%) patients were over 85 years of age. A decreased performance score (≥2) was observed in 44 patients (32%). Among 90 tested patients, 30 (33%) had cytogenetic abnormalities with 13% classified as high risk, because of monosomy 13 or hypodiploidy in conventional G-banding. Twenty-seven of 31 patients with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) had abnormal results. We detected 7 patients (26%) with t(4;14), t(14;16) or deletion 17p among 27 patients with abnormal FISH results. Non-plasma cell malignancies were diagnosed in 45 patients including 33 with solid tumors and 12 with hematologic malignancies. Three patients developed myelodysplastic syndrome following their diagnosis of myeloma. Fourteen (10%) patients also had concomitant AL (Amyloid composed of immunoglobin Light chains) amyloidosis involving the heart, kidney, gastrointestinal tract or soft tissue. Seven patients had plasmacytoma. One hundred and twenty-two patients were treated at Mayo Clinic; 17 patients were not treated because of their poor condition or co-morbidities (n = 15) and patients’ refusal of therapy (n = 2). Front-line therapy consisted of conventional agents in 87 (71%) patients; melphalan and prednisone (MP) or dexamethasone in 82 (67%) patients, dexamethasone alone in 4 and a combination of alkylating agents in 1 patient. Among them, 34 (39%) patients received novel agents for progressive or recurrent disease during the disease course. Novel agents were given to 35 (29%) patients as front-line therapy; lenalidomide and dexamethasone in 8, thalidomide and dexamethasone in 8; melphalan, prednisone and lenalidomide in 6; lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in 6; melphalan, prednisone and thalidomide in 4; and bortezomib-containing regimens in 3. Novel agents as the first-line therapy accounted for over half of the regimens since 2006. The number of patients who received novel agents at any time was 69 (50%). Response to the first therapy was observed in 59 (48%) patients among 122 treated patients. The response rate was 45% in patients with conventional therapy and 57% with novel agents. Complete response (CR) (9%) and near CR was higher (26%) in the 35 patients given novel agents as first-line therapy. Nine patients obtained a CR or near CR, four had a very good partial response (VGPR) and seven had a partial response (PR) from novel agents given as first-line therapy. The response rates are summarized in Figure 1. The response to front-line therapy was not evaluable in 20 patients with conventional agents and 6 with novel agents because of early discontinuation of therapy from toxicity in 23 patients, transfer to another hospital in 2 patients and family decision in 1 patient. Deaths during the first chemotherapy regimen occurred in 10 patients (8%). Death was due to sepsis in three, pancreatitis in one and unknown in six patients. The median duration of front-line therapy was 9 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 8–11) in 121 patients. The progression-free survival from front-line therapy was 20 months (95% CI: 17–24). The median number of regimens was 2 (range: 1–8). Twenty patients are still receiving treatment and 6 patients are still on the first regimen. The median survival of all 212 patients and the 139 patients who were managed at Mayo Clinic were 24 months (95% CI: 18–30) and 27 months (95% CI: 20–35), respectively. These are significantly less than the 62 months (95% CI: 56–68) in patients ≤75 years old (P<0.001) seen during the same time. The median survival of 122 patients receiving therapy was 30 months (95% CI: 12–39) compared with 2 months (95% CI: 0–4) for the 17 patients declining the treatment. Age >85 years, poor performance status (ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) ≥2), thrombocytopenia (platelet <150 000/μl) and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase or β2-microglobulin at diagnosis were significant factors for decreased survival on univariate analysis. Institution of active chemotherapy (versus supportive care only), incorporation of new agents in front-line therapy or at anytime, and achievement of any response were also significant on univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis showed that only poor performance status shortened the survival (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Response (response was assessed using criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group) to front-line therapy according to whether (a) conventional or (b) novel agents (two patients with CR, two VGPR and two PR were assessed for their best response during the front-line therapy with new agents) were used.

Table 1.

The significant factors contributing to overall survival

| Characteristics | Variables | Number of patients | Median survival, months (95% CI) | P valuea | P valueb | 95% CI for hazards (lower-upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 76–85 | 119 | 33 (23–42) | 0.0000 | 0.062 | 0.218 |

| 86 or more | 20 | 4 (2–7) | 1.038 | |||

| Performance statusc | 0–1 | 62 | 30 (22–38) | 0.0142 | 0.031 | 0.312 |

| 2–4 | 44 | 7 (0–15) | 0.947 | |||

| Platelet | ≥150 000/μl | 118 | 32 (22–42) | 0.0342 | 0.658 | 0.324 |

| <150 000/μl | 20 | 12 (6–18) | 1.336 | |||

| LDH | Normal | 110 | 35 (26–44) | 0.0000 | 0.055 | 0.192 |

| Increased | 15 | 4 (0–12) | 1.018 | |||

| β2-Microglobulin | <5.5 mg/dl | 56 | 41 (25–56) | 0.0077 | 0.210 | 0.373 |

| ≥5.5 mg/dl | 67 | 18 (4–32) | 1.241 | |||

| Treatment | Treated | 122 | 30 (21– 39) | 0.0007 | d | d |

| Not treated | 17 | 2 (0–4) | d | |||

| Novel agentse as front-line therapy | Yes | 35 | 40 (22–59) | 0.0591 | 0.807 | 0.508 |

| No | 87 | 22 (11–33) | 2.389 | |||

| Novel agents at any time | Yes | 69 | 40 (28–54) | 0.0008 | 0.162 | 0.293 |

| No | 53 | 13 (5–22) | 1.227 | |||

| Response to first therapyf | CR or NCR | 17 | 51 (39–63) versus | 0.0293 | 0.574 | 0.256 |

| versus ORNE | 105 | 23 (13–33) | 2.127 | |||

| PR or more | 59 | 50 (38–62) versus | 0.0000 | 0.220 | 0.119 | |

| versus ORNE | 63 | 10 (4–15) | 1.630 | |||

| SD or more | 71 | 50 (39–60) versus | 0.0000 | 0.607 | 0.194 | |

| versus ORNE | 51 | 6 (0–12) | 2.607 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NCR, near complete response; ORNE, other response or not evaluable; PR, partial response.

P value in univariate analysis using log-rank test.

P value in multivariate analysis using Cox regression.

Performance status according to criteria of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Variable was excluded after the univariate analysis.

The regimens with novel agents were lenalidomide and dexamethasone (n = 8), thalidomide and dexamethasone (n = 8), MP with lenalidomide (n = 6), cyclophosphamide, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (n = 6) and MP with thalidomide (n = 4) and velcade-containing regimens (n = 3). Otherwise, conventional therapy included melphalan with prednisone (MP) or dexamethasone (n = 82), dexamethasone (n = 4) and VBMCP (n = 1).

Response was assessed using criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group. Bold values are statistically significant at P<0.005.

We focused on the comparison of survival before and after the introduction of novel agents in elderly myeloma patients. Thirty-five patients who received novel agents as first-line therapy as well as 69 patients who received one or more novel agents anytime during the treatment period showed superior survival compared with patients treated with conventional therapy in univariate analysis, but failed to show a survival benefit in multivariate analysis. Salvage therapy with novel agents might explain this result. Patients over 75 years of age who received MP or MP plus thalidomide had a median survival of 44 months compared with 29 months in an IFM (Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome) randomized trial.8 Our retrospective analysis included elderly patients exposed to various novel agents, and the IFM study also included use of novel agents as rescue treatment in patients with progressive disease. We presume that adequate choice of novel agent according to patients’ organ function and modification of dose intensity will prolong the survival of elderly MM patients. The second point is the relation between response to first therapy and survival. Achievement of stabilization or response increased the median survival to 50 months compared with 6 months in patients with progressive or inevaluable disease in our study. The IFM01/01study8 reported higher rates of PR, VGPR and CR in the MP plus thalidomide group, but not an increased survival. They also reported the same overall survival after progression in both the groups. This suggests that appropriate choice of rescue therapy is important in elderly myeloma patients after disease progression. The last comparison is with younger patients in the same period. The significant difference of median survival was observed in our analysis (62 versus 27 months). Elderly patients have more co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, depression or arthritis. In one report patients aged 65 years or more usually had an average of three different concurrent diseases.10 Our study contained the 17 untreated patients because of concurrent diseases. They had a short median survival (2 months versus 30 months for treated patients). Elderly MM patients also have limited social and financial support, and reduced functional status, which may interrupt active treatment. Both elderly patients and their physicians are more likely to choose less intensive or supportive therapy, which may be appropriate in patients with significant co-morbidities.11 The reduction of dose and early termination after toxicity are frequent decisions by physician, patient or family during treatment.

It has not been shown that MM has a more malignant biology in elderly patients. Some reports showed aggressive disease in young MM patients.12–14 Twenty-five percent of our patients had a history of coexistent or subsequent malignancy, which may also shorten the survival. However, there was no significant difference in survival with or without other malignancies (data not shown). AL amyloidosis or plasmacytoma were frequently seen in our elderly MM patients; its frequency was 16.5%. This may result in both reduced organ function and may reflect high tumor burden. In conclusion, myeloma patients over 75 years with a good performance status showed a favorable outcome. They are good candidates for active therapy especially with novel agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by CA-62242 from the National Cancer Institute and the JABBS and Predolin Foundations.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Median age of cancer patients at diagnosis, 2003–2007 by primary cancer site, race and sex. ( http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/results_single/sect_01_table.11_2pgs.pdf)

- 2.Phekoo KJ, Schey SA, Richards MA, Bevan DH, Bell S, Gillett D, et al. A population study to define the incidence and survival of multiple myeloma in a National Health Service Region in UK. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Dickman PW, Derolf AR, Bjorkholm M. Patterns of survival in multiple myeloma: a population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1993–1999. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froom P, Quitt M, Aghai E. Multiple myeloma in the geriatric patient. Cancer. 1990;66:965–967. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900901)66:5<965::aid-cncr2820660526>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bladé J, Muñoz M, Fontanillas M, San Miguel J, Alcalá A, Maldonado J, et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma in elderly people: long-term results in 178 patients. Age Ageing. 1996;25:357–361. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.5.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodon P, Linassier C, Gauvain JB, Benboubker L, Goupille P, Maigre M, et al. Multiple myeloma in elderly patients: presenting features and outcome. Eur J Haematol. 2001;66:11–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anagnostopoulos A, Gika D, Symeonidis A, Zervas K, Pouli A, Repoussis P, et al. Multiple myeloma in elderly patients: prognostic factors and outcome. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75:370–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulin C, Facon T, Rodon P, Pegourie B, Benboubker L, Doyen C, et al. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: IFM 01/01 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3664–3670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:3–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penson RT, Daniels KJ, Lynch TJ., Jr Too old to care? Oncologist. 2004;9:343–352. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-3-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1766–1770. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clough V, Delamore IW, Whittaker JA. Multiple myeloma in a young woman. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:117–118. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-1-117_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khunger JM, Sharma M, Talib VH. Multiple myeloma presenting as primary non-secretory plasma cell leukemia. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46:104–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CC, Gau JP, Ho CH, Lin JS, Chiou HJ, Lirng JF. Aggressive multiple myeloma with brain involvement in a young patient. J Chin Med Assoc. 2003;66:177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]