Abstract

BACKGROUND

Survivors of critical illness often have a prolonged and disabling form of cognitive impairment that remains inadequately characterized.

METHODS

We enrolled adults with respiratory failure or shock in the medical or surgical intensive care unit (ICU), evaluated them for in-hospital delirium, and assessed global cognition and executive function 3 and 12 months after discharge with the use of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (population age-adjusted mean [±SD] score, 100±15, with lower values indicating worse global cognition) and the Trail Making Test, Part B (population age-, sex-, and education-adjusted mean score, 50±10, with lower scores indicating worse executive function). Associations of the duration of delirium and the use of sedative or analgesic agents with the outcomes were assessed with the use of linear regression, with adjustment for potential confounders.

RESULTS

Of the 821 patients enrolled, 6% had cognitive impairment at baseline, and delirium developed in 74% during the hospital stay. At 3 months, 40% of the patients had global cognition scores that were 1.5 SD below the population means (similar to scores for patients with moderate traumatic brain injury), and 26% had scores 2 SD below the population means (similar to scores for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease). Deficits occurred in both older and younger patients and persisted, with 34% and 24% of all patients with assessments at 12 months that were similar to scores for patients with moderate traumatic brain injury and scores for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease, respectively. A longer duration of delirium was independently associated with worse global cognition at 3 and 12 months (P = 0.001 and P = 0.04, respectively) and worse executive function at 3 and 12 months (P = 0.004 and P = 0.007, respectively). Use of sedative or analgesic medications was not consistently associated with cognitive impairment at 3 and 12 months.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients in medical and surgical ICUs are at high risk for long-term cognitive impairment. A longer duration of delirium in the hospital was associated with worse global cognition and executive function scores at 3 and 12 months. (Funded by the National Institutes of Health and others; BRAIN-ICU ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00392795.)

Survivors of critical illness frequently have a prolonged and poorly understood form of cognitive dysfunction,1-4 which is characterized by new deficits (or exacerbations of preexisting mild deficits) in global cognition or executive function. This long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness may be a growing public health problem, given the large number of acutely ill patients being treated in intensive care units (ICUs) globally.5 Among older adults, cognitive decline is associated with institutionalization,6 hospitalization,7 and considerable annual societal costs.8,9 Yet little is known about the epidemiology of long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness.

Delirium, a form of acute brain dysfunction that is common during critical illness, has consistently been shown to be associated with death,10,11 and it may be associated with long-term cognitive impairment.12 In addition, factors that have been associated with delirium, including the use of sedative and analgesic medications, may independently contribute to long-term cognitive impairment.13,14

Data on the prevalence of long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness have largely come from small cohort studies restricted to single disease processes (e.g., the acute respiratory distress syndrome)1,15,16 or from large, longitudinal cohort studies lacking details of in-hospital risk factors for long-term cognitive impairment.3,4 We conducted a multicenter, prospective cohort study of a diverse population of critically ill patients to estimate the prevalence of long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness and to test our hypothesis that a longer duration of delirium in the hospital and higher doses of sedative and analgesic agents are independently associated with more severe cognitive impairment up to 1 year after hospital discharge.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION AND SETTING

The Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors (BRAIN-ICU) study was conducted at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Saint Thomas Hospital in Nashville. Detailed definitions of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Briefly, we included adults admitted to a medical or surgical ICU with respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, or septic shock. We excluded patients with substantial recent ICU exposure (i.e., receipt of mechanical ventilation in the 2 months before the current ICU admission, >5 ICU days in the month before the current ICU admission, or >72 hours with organ dysfunction during the current ICU admission); patients who could not be reliably assessed for delirium owing to blindness, deafness, or inability to speak English; patients for whom follow-up would be difficult owing to active substance abuse, psychotic disorder, homelessness, or residence 200 miles or more from the enrolling center; patients who were unlikely to survive for 24 hours; patients for whom informed consent could not be obtained; and patients at high risk for preexisting cognitive deficits owing to neurodegenerative disease, recent cardiac surgery (within the previous 3 months), suspected anoxic brain injury, or severe dementia. Specifically, patients who were suspected to have preexisting cognitive impairment on the basis of a score of 3.3 or more on the Short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE; on a scale from 1.0 to 5.0, with 5.0 indicating severe cognitive impairment)17 were assessed by certified evaluators with the use of the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale (with scores ranging from 0 to 3.0, and higher scores indicating more severe dementia).18 Patients with a CDR score of more than 2.0 were excluded (additional information on the IQCODE and CDR is provided in the Supplementary Appendix).

At enrollment, we obtained written informed consent from all the patients or their authorized surrogates; if consent was initially obtained from a surrogate, we obtained consent from the patient once he or she was deemed to be mentally competent. The study protocol was approved by each local institutional review board.

RISK FACTORS, OUTCOMES, AND COVARIATES

We examined two primary independent risk factors: duration of delirium (defined as the number of hospital days with delirium) and use of sedative or analgesic medications during hospitalization. Trained research personnel evaluated patients for delirium and level of consciousness daily until hospital discharge or study day 30. Delirium was assessed with the use of the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU), a diagnostic algorithm for determining the presence or absence of delirium on the basis of four features: acute change or a fluctuation in mental status, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness.19 Level of consciousness was assessed with the use of the Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS), on which scores range from −5 to 4, with lower scores indicating less arousal, higher scores indicating more agitation, and 0 indicating an alert and calm state.20 Throughout the hospitalization, we used medication-administration records to collect information on daily doses of benzodiazepines (converted to midazolam dose equivalents), opiates (converted to fentanyl dose equivalents), propofol, and dexmedetomidine. Conversion factors are described in the Supplementary Appendix.

Trained psychology professionals, who were unaware of the patients’ in-hospital course, assessed patients’ global cognition 3 and 12 months after hospital discharge using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), a comprehensive and validated neuropsychometric battery for the evaluation of global cognition, including individual domains of immediate and delayed memory, attention, visuo-spatial construction, and language.21 The population age-adjusted mean (±SD) for the RBANS global cognition score and for the individual domains is 100±15 (on a scale ranging from 40 to 160, with lower scores indicating worse performance). In addition, executive function (specifically, cognitive flexibility and set shifting) was assessed with the use of the Trail Making Test, Part B (Trails B)22; the age-, sex-, and education-adjusted mean T score is 50 (on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating worse executive function). All follow-up assessments are described in detail in the Supplementary Appendix.

All covariates were chosen a priori on the basis of clinical judgment and previous research, owing to their expected associations with the outcomes and with delirium, and thus their potential to be confounders. Details of the covariates and the range and clinical significance of specific scores are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. Briefly, covariates that were determined at enrollment included age, years of education, chronic disease burden according to the Charlson comorbidity index (on a scale ranging from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating a greater burden of coexisting conditions),23 preexisting cognitive impairment according to the Short IQCODE,17 cerebrovascular disease as assessed by means of the Framingham Stroke Risk Profile,24 and apolipoprotein E genotype. Covariates that were measured daily until ICU discharge or study day 30 included severity of illness as assessed by means of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA; scores range from 0 to 24 [from 0 to 4 for each of six organ systems], with higher scores indicating more severe organ dysfunction),25 mean daily dose of haloperidol, and duration of severe sepsis, hypoxemia, and coma.

MANAGEMENT OF MISSING DATA

Because missing data rarely occur entirely at random,26 we assessed the associations between characteristics of the patient and status with respect to missing data according to recommendations.27 Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix shows the frequency of missing outcomes, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix shows that patients with at least one missing outcome value were different from those with complete outcomes data in small but potentially meaningful ways. The exclusion of such patients may have biased our results, so we used multiple imputation to assign values to missing risk factors and outcomes in regression modeling. However, we did not impute data for patients who had no cognitive-outcomes data (e.g., owing to death or withdrawal from the study).

We used single imputation for missing delirium and coma assessments. Of 10,558 patient-days during which delirium or coma assessments were expected, only 3% were missing and required imputation.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To determine whether the duration of delirium and the doses of sedative or analgesic agents (including benzodiazepines, propofol, dexmedetomidine, and opiates) were independent risk factors for the primary outcome variable (RBANS global cognition score), we used multiple linear regression with adjustment for all aforementioned covariates in separate models for the outcomes at 3 and 12 months. Similarly, we used multiple linear regression to determine whether the duration of delirium and the doses of sedative or analgesic agents were independently associated with secondary outcomes (Trails B score and RBANS scores for immediate memory, delayed memory, and attention) at 3 and 12 months. Because we hypothesized that delirium and coma may interact in their association with long-term cognitive impairment, we assessed the data for such interactions in all regression models.

In all models, drug doses were transformed with the use of their cube root to reduce the influence of extreme outliers, and continuous variables were modeled with the use of restricted cubic splines to allow for nonlinear associations (with the exception of dexmedetomidine and haloperidol doses, which were used so infrequently that the number of unique doses was too small for splines).28 We also conducted sensitivity analyses that were restricted to data for patients who underwent all outcome assessments (i.e., a complete case analysis). To determine whether an altered level of consciousness confounded the association between delirium and long-term cognitive impairment, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with adjustment for duration of an altered level of consciousness. Since days of delirium and coma were already accounted for in our regression models, we included as a separate covariate the number of days without delirium and without coma but with an altered level of consciousness (defined as a RASS score other than 0). We also examined ICU type (medical vs. surgical) as a potential confounder by including this variable in models in a separate sensitivity analysis. We examined model diagnostics using residual plots versus predicted plots and quantile–quantile plots. All model assumptions were met adequately. Variance inflation due to multiple imputation was not problematic. We used R software, version 3.0.1 (www.r-project.org), for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS

Between March 2007 and May 2010, we enrolled 826 patients (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). A total of 5 patients withdrew consent and permission to use their collected data; thus, we included 821 patients, who had a median age of 61 years and a high severity of illness (Table 1). Only 51 patients (6%) had evidence of preexisting cognitive impairment (Table 1). Delirium affected 606 patients (74%) during their hospital stay, with a median duration of delirium of 4 days.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients.*

| Characteristic | In-Hospital Cohort (N = 821) | Follow-up Cohort (N = 467) |

|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | ||

| Median | 61 | 59 |

| Interquartile range | 51-71 | 49-69 |

| White race — no. (%)† | 740 (90) | 413 (88) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 420 (51) | 234 (50) |

| Medical ICU — no. (%) | 559 (68) | 298 (64) |

| Level of education — yr | ||

| Median | 12 | 12 |

| Interquartile range | 12-14 | 12-14 |

| Short IQCODE score ≥3.6 — no. (%)‡ | 51 (6) | 26 (6) |

| CDR score of 1 or 2 — no. (%)§ | 45 (5) | 23 (5) |

| Charlson comorbidity index¶ | ||

| Median | 2 | 2 |

| Interquartile range | 1-4 | 1-4 |

| APACHE II score at enrollment∥ | ||

| Median | 25 | 24 |

| Interquartile range | 19-31 | 19-30 |

| SOFA score at enrollment** | ||

| Median | 9 | 9 |

| Interquartile range | 7-12 | 7-12 |

| Diagnosis at admission — no. (%) | ||

| Sepsis | 244 (30) | 136 (29) |

| Acute respiratory failure†† | 135 (16) | 71 (15) |

| Cardiogenic shock, myocardial ischemia, or arrhythmia | 141 (17) | 79 (17) |

| Upper-airway obstruction | 87 (11) | 49 (10) |

| Gastric or colonic surgery | 63 (8) | 29 (6) |

| Neurologic disease or seizure | 11 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Other surgical procedure‡‡ | 82 (10) | 65 (14) |

| Other diagnosis | 58 (7) | 31 (7) |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||

| No. of patients — % | 746 (91) | 421 (90) |

| No. of days | ||

| Median | 3 | 2 |

| Interquartile range | 1-8 | 1-6 |

| Delirium | ||

| No. of patients — % | 606 (74) | 352 (75) |

| No. of days | ||

| Median | 4 | 3 |

| Interquartile range | 2-7 | 2-7 |

| Coma | ||

| No. of patients — % | 517 (63) | 265 (57) |

| No. of days | ||

| Median | 3 | 3 |

| Interquartile range | 2-6 | 1-5 |

| Duration of hospital stay — days | ||

| Median | 10 | 10 |

| Interquartile range | 6-17 | 6-18 |

| Use of sedative or analgesic agent in ICU — no. (%) | ||

| Benzodiazepine | 509 (62) | 274 (59) |

| Propofol | 425 (52) | 256 (55) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 105 (13) | 63 (13) |

| Opiate | 641 (78) | 362 (78) |

Percentages may not sum to 100, owing to rounding. Of the 821 patients for whom in-hospital data and assessments were available, 467 underwent follow-up assessments at 3 months, 12 months, or both. A total of 354 patients did not undergo follow-up (252 patients died and 74 withdrew from the study before the 3-month assessment, and 28 were permanently lost to follow-up). ICU denotes intensive care unit.

Race was determined according to the medical record or was reported by the patient's surrogate.

Scores on the Short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) range from 1 to 5, with a score of 3 indicating no change in cognition over the past 10 years, a score lower than 3 indicating improvement, and a score higher than 3 indicating decline in cognition, as compared with 10 years before. A score of 3.3 or higher indicates an increased probability of cognitive impairment, and a score of 3.6 or higher indicates preexisting cognitive impairment (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale range from 0 to 3.0, with 0 indicating no impairment, 0.5 very mild impairment, 1.0 mild impairment, 2.0 moderate impairment, and 3.0 severe impairment.

Scores on the Charlson comorbidity index range from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating a greater burden of illness; a score of 1 or 2 is associated with mortality of approximately 25% at 10 years.

Scores on the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II range from 0 to 71, with higher scores indicating worse outcomes.

Scores on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) range from 0 to 24 (from 0 to 4 for each of six organ systems), with higher scores indicating more severe organ dysfunction. We used a modified SOFA score in our regression models, which excluded the Glasgow Coma Scale components, since coma was included separately in our models.

Acute respiratory failure included the acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, pulmonary edema, embolus, and fibrosis.

Other surgical procedures included hepatobiliary surgery, liver transplantation, and orthopedic, obstetrical or gynecologic, vascular, otolaryngologic, and urologic surgery.

Between enrollment and the 3-month follow-up, 252 patients (31%) died; 448 of the 569 surviving patients (79%) underwent cognitive testing 3 months after discharge. Another 59 patients (7% of the original cohort) died before the 12-month follow-up, and 382 of the 510 surviving patients (75%) were tested 12 months after discharge (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

PREVALENCE AND SEVERITY OF LONG-TERM COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

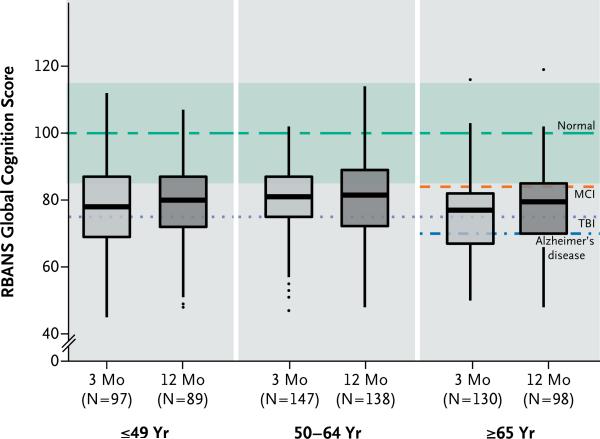

Median RBANS global cognition scores at 3 and 12 months were 79 (interquartile range, 70 to 86) and 80 (interquartile range, 71 to 87), respectively. These scores were approximately 1.5 SD below the age-adjusted population mean of 100±15 and were similar to scores for patients with mild cognitive impairment.29 At 3 months, 40% of the patients had global cognition scores that were worse than those typically seen in patients with moderate traumatic brain injury,30 and 26% had scores 2 SD below the population means, which were similar to scores for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 1).31 Deficits of this severity were also common at 12 months, with 34% and 24% of patients having scores similar to those for patients with moderate traumatic brain injury and those for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease, respectively.30,31

Figure 1. Global Cognition Scores in Survivors of Critical Illness.

The box-and-whisker plots show the age-adjusted global cognition scores on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS; with a population age-adjusted mean [±SD] of 100±15, and lower scores indicating worse global cognition) at 3 months (light-gray boxes) and 12 months (dark-gray boxes), according to age. For each box-and-whisker plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median, the upper and lower limits of the boxes the interquartile range, and the ends of the whiskers 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outliers are shown as black dots. The green dashed line indicates the age-adjusted population mean (100) for healthy adults, and the green band indicates the standard deviation (15). Also shown are the expected population means for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), moderate traumatic brain injury (TBI), and mild Alzheimer's disease on the basis of other cohort studies. Expected population means for MCI and Alzheimer's disease are shown only for patients 65 years of age or older, since RBANS population norms for these disorders have been generated only in that age group.

Cognitive impairment was not limited to older patients or to patients with coexisting conditions at baseline. Patients who were 49 years of age or younger, for example, had median global cognition scores of 78 and 80 at 3 and 12 months, respectively (Fig. 1, and Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In addition, global cognition scores were low regardless of the burden of coexisting conditions (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Even among patients 49 years of age or younger with no coexisting conditions at baseline, 34% had global cognition scores at the 12-month follow-up that were commensurate with moderate traumatic brain injury, and approximately 20% had results similar to those for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. Unlike Alzheimer's disease, however, which affects delayed memory much more than other domains, long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness tended to affect multiple cognitive domains (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The Trails B executive-function scores were also low at 3 and 12 months; median scores of 41 and 42, respectively, were below population norms, regardless of the patient's age (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

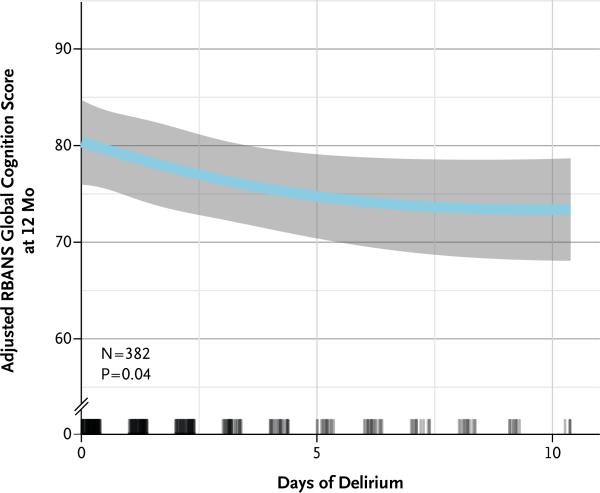

DELIRIUM, SEDATIVE AND ANALGESIC MEDICATIONS, AND LONG-TERM COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

A longer duration of delirium was an independent risk factor for worse RBANS global cognition scores at both 3 and 12 months after discharge (P = 0.001 and P = 0.04, respectively) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). However, the duration of coma was not associated with RBANS scores at either 3 or 12 months after discharge (P = 0.87 and P = 0.79, respectively), although it did modify the association between delirium and global cognition scores at 3 months (P = 0.05 for interaction) (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). A longer duration of delirium was also an independent risk factor for worse executive function at 3 and 12 months (P = 0.004 and P = 0.007, respectively) (Table 2, and Fig. S4 and S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). A longer duration of delirium was also a risk factor for worse function in several individual RBANS domains (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2.

Effect of Duration of Delirium, Duration of Coma, and Exposure to Sedative or Analgesic Agents on Global Cognition and Executive Function.*

| Independent Variable | Percentile† | RBANS Global Cognition Score | Trails B Executive-Function Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 75th | At 3 Mo | At 12 Mo | At 3 Mo | At 12 Mo | |||||

| difference (95%, CI) | P value | difference (95%, CI) | P value | difference (95%, CI) | P value | difference (95%, CI) | P value | |||

| Duration of delirium (days) | 0 | 5 | −6.3 (−10.3 to −2.3) | 0.001 | −5.6 (−9.5 to −1.8) | 0.04 | −5.1 (−9.2 to −1.1) | 0.004 | −6.0 (−10.2 to −1.9) | 0.007 |

| Duration of coma (days) | 0 | 4 | −1.5 (−7.0 to 4.1) | 0.12 | 1.2 (−3.3 to 5.7) | 0.87 | −1.6 (−6.1 to 2.9) | 0.70 | 0.9 (−3.8 to 5.6) | 0.79 |

| Mean daily dose of sedative or analgesic agent‡ | ||||||||||

| Benzodiazepine (mg) | 0 | 7.88 | 0.3 (−2.9 to 3.5) | 0.20 | −0.4 (−3.9 to 3.0) | 0.17 | −2.9 (−6.9 to 1.0) | 0.04 | −0.5 (−4.4 to 3.5) | 0.19 |

| Propofol (mg) | 0 | 804 | 0.5 (−2.2 to 3.3) | 0.83 | −0.4 (−3.4 to 2.7) | 0.96 | −1.4 (−4.6 to 1.7) | 0.44 | −1.7 (−5.1 to 1.7) | 0.61 |

| Dexmedetomidine (μg) | 0 | 3826 | −4.0 (−11.7 to 3.7) | 0.31 | −5.7 (−14.1 to 2.8) | 0.19 | −2.5 (−11.2 to 6.1) | 0.57 | −0.4 (−9.5 to 8.7) | 0.93 |

| Opiate (mg) | 13.3 | 1238.8 | 3.5 (0.1 to 6.9) | 0.14 | 1.7 (−2.1 to 5.4) | 0.04 | 5.2 (1.4 to 9.1) | 0.06 | 4.6 (0.4 to 8.8) | 0.09 |

Results shown are from linear regression models in which outcome variables were global cognition scores on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS; on a scale from 40 to 160, with lower scores indicating worse performance) or the Trail Making Test, Part B (Trails B; with scores ranging from 0 to 100, and lower scores indicating worse executive function), the independent variables were duration of delirium, duration of coma, and mean dose of sedative or analgesic medications (all included simultaneously in the model), and the covariates were the following potential confounders, which were selected a priori: age, educational level, coexisting conditions, preexisting cognitive impairment, apolipoprotein E genotype, stroke risk, and ICU variables, including the mean scores for the severity of illness, mean haloperidol dose, duration of severe sepsis, duration of hypoxemia, and an interaction between delirium and coma.

Differences (point estimates) in the RBANS and the Trails B scores in the linear regression analyses reflect a comparison between the 25th and the 75th percentile values for each variable among all 821 patients in the original cohort (with the exception of dexmedetomidine dose; because more than 85% of patients received no dexmedetomidine, we used the minimum and maximum doses instead). For example, in a comparison of patients with no delirium and those with 5 days of delirium, with all other covariates held constant, patients with 5 days of delirium had RBANS global cognition scores that were 5.6 points lower at 12 months than did those with no delirium. This represents a decrease of approximately 0.5 SD, which is considered to be a clinically significant decline (see the Supplementary Appendix). A similar comparison of executive-function scores at 3 and 12 months showed a decrease of 0.5 SD in the scores for patients with 5 days of delirium, which is a clinically significant decline according to the neuropsychology literature. CI denotes confidence interval.

We used restricted cubic splines for all continuous variables, which allows for a nonlinear relationship between covariates and outcomes but requires multiple beta coefficients to estimate the effect. The most appropriate P value is one that takes into consideration all these beta coefficients together. Although the P value may indicate significance (and is correct), the comparison of the 25th and 75th percentiles may yield a point estimate with a confidence interval that crosses zero, or vice versa.

Figure 2. Duration of Delirium and Global Cognition Score at 12 Months.

Longer durations of delirium were independently associated with worse RBANS global cognition scores at 12 months. Point estimates and the 95% confidence interval for these relationships are shown by the blue line and the gray band, respectively. RBANS global cognition scores have age-adjusted population norms, with a mean (±SD) score of 100±15. Rug plots show the distribution of the durations of delirium. Although delirium could be assessed for up to 30 days in the study, the x axis is truncated at 10 days because 90% of the patients had delirium for 10 days or less; all available data were used in the multivariable modeling. As one example, in a comparison of patients with no delirium and those with 5 days of delirium (the 25th and 75th percentile values of delirium duration in our cohort), with all other covariates held constant (at the median or mode of the covariate), patients with 5 days of delirium had RBANS global cognition scores at 12 months that were an average of 5.6 points lower than the scores for patients with no delirium.

We did not observe an independent association between higher doses of benzodiazepines and worse long-term cognitive scores, except that higher benzodiazepine doses were an independent risk factor for worse executive-function scores at 3 months (P = 0.04) (Table 2). None of the other medications examined, including propofol, dexmedetomidine, and opiates, were consistently associated with global cognition or executive-function outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses that included only patients for whom complete outcome data were available yielded similar results (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). In addition, adjustments for an altered level of consciousness and surgical versus medical ICU did not qualitatively change our findings.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter, prospective cohort study involving a diverse population of patients in general medical and surgical ICUs, we found that one out of four patients had cognitive impairment 12 months after critical illness that was similar in severity to that of patients with mild Alzheimer's disease, and one out of three had impairment typically associated with moderate traumatic brain injury. Impairments affected a broader array of neuropsychological domains than is characteristically seen in Alzheimer's disease, but the impairments were very similar to those observed after moderate traumatic brain injury. A validated instrument that assessed baseline cognitive status showed that only 6% of patients had evidence of mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment before ICU admission, indicating that these profound cognitive deficits were new in the majority of patients. Long-term cognitive impairment affected both old and young patients, regardless of the burden of coexisting conditions at baseline.

A longer duration of delirium was associated with worse long-term global cognition and executive function, an association that was independent of sedative or analgesic medication use, age, preexisting cognitive impairment, the burden of coexisting conditions, and ongoing organ failures during ICU care. Although the mechanisms by which delirium may predispose patients to long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness have not yet been elucidated, delirium is associated with inflammation and neuronal apoptosis, which may lead to brain atrophy.32,33 Delirium has previously been associated with cerebral atrophy34 and reduced white-matter integrity35; both atrophy and white-matter disruption are associated with cognitive impairment.34,35 It is also possible that patients who are vulnerable to delirium owing to severe critical illness are also vulnerable to long-term cognitive impairment and that delirium does not play a causal role in the development of persistent cognitive impairment.

After adjustment for delirium, we did not find any consistent associations between the use of sedative or analgesic medications and long-term cognitive impairment. The significant association between benzodiazepines and executive function at 3 months should be interpreted cautiously, owing to multiple testing and the nonsignificant associations between benzodiazepines and global cognition scores at 12 months. However, the lack of a consistent association should not be taken to suggest that large doses of sedatives are safe, given studies showing that oversedation is associated with adverse outcomes.36

Since delirium is associated with long-term cognitive impairment, interventions directed at reducing delirium may mitigate brain injury associated with critical illness. Although the judicious use of sedative agents and routine monitoring for delirium — recommended components of care for all patients in the ICU37 — are increasingly applied, only a few interventions (e.g., early mobilization and sleep protocols) have been shown to reduce the risk of delirium among patients in the ICU,38-40 and it is not known whether any preventive or treatment strategies can reduce the risk of long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness.

These results complement those of earlier cohort studies that exposed the problem of cognitive deficits in survivors of critical illness.1-4 Some important differences, however, exist between previous investigations and the BRAIN-ICU study. First, we enrolled a large sample of patients with a diverse set of admission diagnoses and a broad age range. Second, we collected and analyzed detailed data about delirium and sedative exposure as risk factors for long-term cognitive impairment. Two longitudinal studies3,4 have advanced the field, but one was limited to patients with severe sepsis,4 and neither study collected detailed data on in-hospital exposures, such as delirium and psychoactive medications. In addition, the previous studies assessed cognitive outcomes with the use of abbreviated screening tools, which do not allow comparisons with other populations, such as patients with traumatic brain injury or Alzheimer's disease.

An important limitation of the BRAIN-ICU study was our inability to test patients’ cognition before their emergent illness. We addressed this limitation in three ways. First, we excluded patients who were found to have severe dementia with the use of a rigorous and well-validated approach that relied on two validated surrogate assessment tools, the widely used Short IQCODE17 and the reference standard CDR scale.18 Second, we used the Short IQCODE to estimate preexisting cognitive function in all patients 50 years of age or older and in those younger than 50 years of age with memory problems, and we adjusted for this measure as a continuous variable in our regression models. Third, we stratified cognitive outcomes according to age and burden of coexisting illness and found that even young patients with no coexisting conditions — that is, patients who were highly unlikely to have any preexisting cognitive impairment — were also at high risk for long-term cognitive impairment (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Another limitation of our study is that, despite high follow-up rates, some patients were unable to complete all cognitive tests. We used imputation strategies in our main analysis to reduce potential bias due to missing data and conducted sensitivity analyses that were restricted to data from patients with complete assessments, with similar results. We were not able, however, to address the possibility of confounding by death or withdrawal. Finally, as with any observational study, the possibility of bias due to unmeasured confounders cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, cognitive impairment after critical illness is very common and in some patients persists for at least 1 year. Patients with a longer duration of delirium are more likely than those with a shorter duration of delirium to have cognitive deficits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG027472; HL111111, to Drs. Pandharipande, Hughes, Dittus, and Ely; AG035117, to Drs. Pandharipande, Bernard, Dittus, and Ely; AG034257, to Dr. Girard; AG031322, to Dr. Jackson; AG040157, to Dr. Vasilevskis; and NHLBI 2 T32 HL087738-06, to Drs. Brummel and Bernard) and the Veterans Affairs (VA) Clinical Science Research and Development Service (to Drs. Pandharipande, Dittus, and Ely), a Mentored Research Training Grant from the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (to Dr. Hughes), and the VA Tennessee Valley Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (to Drs. Girard, Vasilevskis, Dittus, and Ely).

APPENDIX

The authors’ full names, degrees, and affiliations are as follows: Pratik P. Pandharipande, M.D., M.S.C.I., the Department of Anesthesiology, Division of Critical Care, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the Anesthesia Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville; Timothy D. Girard, M.D., M.S.C.I., the Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, and the Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville; James C. Jackson, Psy.D., the Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, the Center for Health Services Research, and the Department of Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville; Alessandro Morandi, M.D., M.P.H., the Rehabilitation and Aged Care Unit, Hospital Ancelle, Cremona, and the Geriatric Research Group, Brescia — both in Italy; Jennifer L. Thompson, M.P.H., the Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville; Brenda T. Pun, R.N., M.S.N., the Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville; Nathan E. Brummel, M.D., M.S.C.I., the Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, and the Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville; Christopher G. Hughes, M.D., the Department of Anesthesiology, Division of Critical Care, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the Anesthesia Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville; Eduard E. Vasilevskis, M.D., M.P.H., the Center for Health Services Research and the Department of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the GRECC, Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville; Ayumi K. Shintani, Ph.D., M.P.H., the Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville; Karel G. Moons, Ph.D., the Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, and the Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Sunil K. Geevarghese, M.D., M.S.C.I., the Department of Surgery, Division of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville; Angelo Canonico, M.D., Saint Thomas Hospital, Nashville; Ramona O. Hopkins, Ph.D., the Department of Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Division, Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, and the Psychology Department and Neuroscience Center, Brigham Young University, Provo — both in Utah; Gordon R. Bernard, M.D., the Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville; Robert S. Dittus, M.D., M.P.H., the Center for Health Services Research and the Department of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the GRECC, Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville; and E. Wesley Ely, M.D., M.P.H., the Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, and the Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the GRECC, Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System — both in Nashville.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Pope D, Orme JF, Bigler ED, Larson-Lohr V. Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:50–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9708059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, et al. Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1226–34. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:763–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. 2010;376:1339–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agüero-Torres H, von Strauss E, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Institutionalization in the elderly: the role of chronic diseases and dementia: cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chodosh J, Seeman TE, Keeler E, et al. Cognitive decline in high-functioning older persons is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1456–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood K, Brown M, Merry H, Sketris I, Fisk J. Societal costs of vascular cognitive impairment in older adults. Stroke. 2002;33:1605–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000017878.85274.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:770–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291:1753–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1092–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0537OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1513–20. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, et al. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:21–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1297–304. doi: 10.1007/s001340101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orme JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorm AF. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): a review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:275–93. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berg L. Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:637–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286:2703–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:310–9. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead Reitan neuropsychological test battery. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson, AZ: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Xie J, Huppert FA, Melzer D, Langa KM. Framingham Stroke Risk Profile and poor cognitive function: a population-based study. BMC Neurol. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Mélot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1754–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little RJ, D'Agostino R, Cohen ML, et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1355–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrell FE., Jr . Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobson VL, Hall JR, Humphreys-Clark JD, Schrimsher GW, O'Bryant SE. Identifying functional impairment with scores from the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:525–30. doi: 10.1002/gps.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay C, Casey JE, Wertheimer J, Fichtenberg NL. Reliability and validity of the RBANS in a traumatic brain injured sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randolph C. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Gool WA, van de Beek D, Eikelen-boom P. Systemic infection and delirium: when cytokines and acetylcholine collide. Lancet. 2010;375:773–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham C. Systemic inflammation and delirium: important co-factors in the progression of dementia. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:945–53. doi: 10.1042/BST0390945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunther ML, Morandi A, Krauskopf E, et al. The association between brain volumes, delirium duration, and cognitive outcomes in intensive care unit survivors: the VISIONS cohort magnetic resonance imaging study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2022–32. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318250acc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morandi A, Rogers BP, Gunther ML, et al. The relationship between delirium duration, white matter integrity, and cognitive impairment in intensive care unit survivors as determined by diffusion tensor imaging: the VISIONS prospective cohort magnetic resonance imaging study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2182–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318250acdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shehabi Y, Bellomo R, Reade MC, et al. Early intensive care sedation predicts long-term mortality in ventilated critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:724–31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0522OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riker RR, Shehabi Y, Bokesch PM, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:489–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:800–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182746442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.