Summary

Bacterial conjugation systems are highly promiscuous macromolecular transfer systems that impact human health significantly. In clinical settings, conjugation is exceptionally problematic, leading to the rapid dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and other virulence traits among bacterial populations. Recent work has shown that several pathogens of plants and mammals – Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Bordetella pertussis, Helicobacter pylori and Legionella pneumophila – have evolved secretion pathways ancestrally related to conjugation systems for the purpose of delivering effector molecules to eukaryotic target cells. Each of these systems exports distinct DNA or protein substrates to effect a myriad of changes in host cell physiology during infection. Collectively, secretion pathways ancestrally related to bacterial conjugation systems are now referred to as the type IV secretion family. The list of putative type IV family members is increasing rapidly, suggesting that macromolecular transfer by these systems is a widespread phenomenon in nature.

Introduction

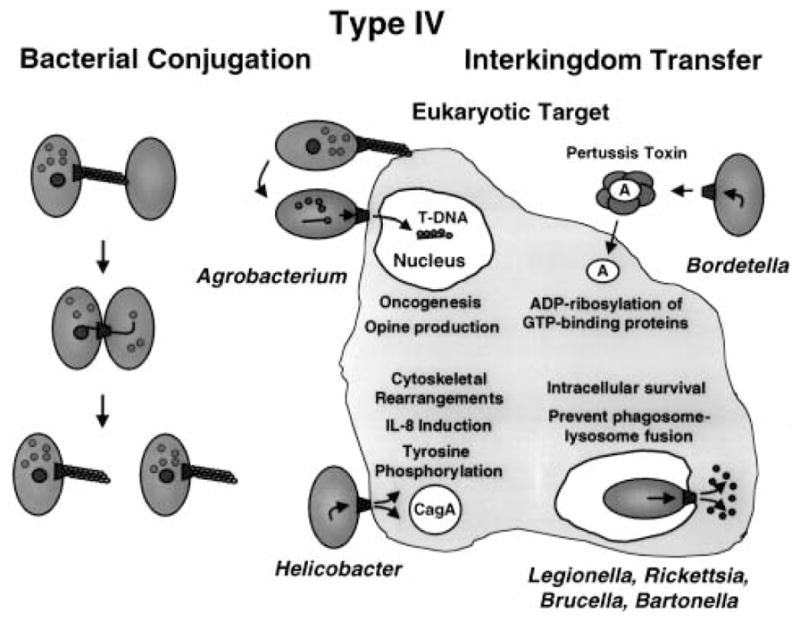

Conjugal transfer across the cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by a supramolecular structure termed the mating pair formation (Mpf) complex. The Mpf is composed of a conjugal pilus for establishing contact with recipient cells and a mating channel through which the DNA transfer intermediate is translocated (Fig. 1). Recent work has shown that several pathogens use secretion systems whose subunits are evolutionarily related to those of Mpf complexes for delivering effector molecules to eukaryotic cells. For example, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a phytopathogen that induces tumorous growth of infected plant tissues, uses such a mechanism to transfer oncogenic T-DNA and several effector proteins to the nuclei of plant cells. Helicobacter pylori, a causative agent of gastric pathologies such as peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma, uses a related system to deliver the 145 kDa CagA protein to mammalian cells. Several intracellular pathogens, including Legionella pneumophila, Brucella spp. and Bartonella spp., are thought to transfer effector proteins upon uptake by macrophages that aid in intracellular survival. Although these systems are envisaged to transfer substrates via direct contact with eukaryotic membranes, this is not obligatory, as exemplified by the Ptl system of Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough. The Ptl system exports its substrate, pertussis toxin (PT), to the extracellular milieu, where it then establishes contact with the mammalian target cell (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The type IV secretion family includes conjugation machines and ancestrally related systems that deliver effector molecules to eukaryotic cells.

Macromolecular transfer systems ancestrally related to the conjugal Mpf complexes are called type IV secretion systems, as originally proposed by Salmond (1994). This nomenclature distinguishes the conjugation-related systems from other bacterial secretion pathways, such as the type I or ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter super-family (Linton and Higgins, 1998) and the types II, III and V secretion systems (reviewed by Sandqvist, 2001, Plano et al., 2001; Jacob-Dubuisson, 2001 respectively). We recently referred to type IV secretion pathways as ‘adapted conjugation’ systems (Christie and Vogel, 2000). This term implies that the Mpf systems that function in DNA translocation are the progenitor structures from which the type IV secretion pathways evolved. However, as summarized in this review, it is now evident that the unifying mechanistic feature – and perhaps common ancestral function – among the type IV secretion systems is the capacity to transfer protein substrates intercellularly. Conjugation systems appear to be a subgroup of type IV systems that have evolved the additional capacity to translocate DNA–protein complexes. Thus, for the present, the consensus view is that we define type IV secretion pathways as macromolecular transfer systems that share a common ancestry with the conjugation (Mpf) machines of Gram-negative bacteria.

Several recent reviews have described the members of the type IV family and summarized the structure–function work on representative systems (Burns, 1999; Covacci et al., 1999; Christie and Vogel, 2000; Lai and Kado, 2000). The aim of the current review is to update this information, but also to present a broader mechanistic perspective of how the type IV systems might generally contribute to pathogenesis.

Type IV systems

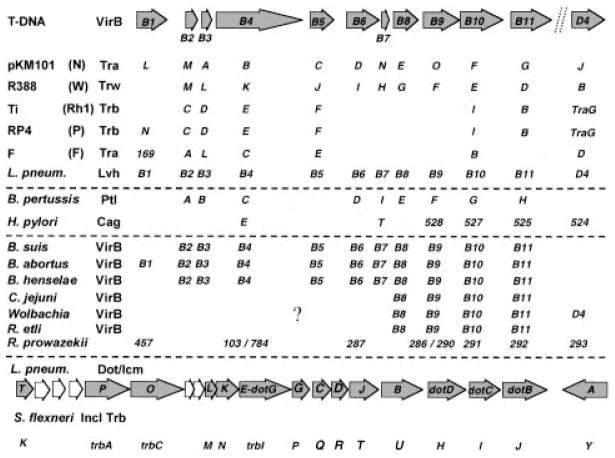

Historically, the A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system has been the reference point for the type IV systems (Salmond, 1994; Covacci et al., 1999). This system is assembled from products of the ≈ 9.5 kb virB operon and the virD4 gene. As shown in Fig. 2, several members of the type IV family share a common ancestry with the T-DNA transfer system. Some of these systems are assembled from a complete set of proteins homologous to the A. tumefaciens VirB proteins, whereas other systems are hybrids of VirB proteins and proteins of unrelated ancestry. Representatives of systems dedicated to conjugal DNA transfer include the plasmid transfer (Tra) systems of the F (IncF), RP4 (IncP), pKM101 (IncN) and R388 (IncW) plasmids (Lai and Kado, 2000). Representatives of systems shown or postulated to export effector proteins include the B. pertussis Ptl secretion system (Burns, 1999), the H. pylori Cag system (Covacci et al., 1999) and the VirB systems of Brucella suis (O’Callaghan et al., 1999; Foulongne et al., 2000), Brucella abortus (Hong et al., 2000; Sieira et al., 2000) and Bartonella henselae (Padmalayam et al., 2000; Schmiederer and Anderson, 2000). Very recently, a set of VirB homologues was shown to contribute to the virulence of Campylobacter jejuni (Bacon et al., 2000), probably adding another member to this secretion family.

Fig. 2.

The type IV systems known or postulated to translocate macromolecular substrates intercellularly. The A. tumefaciens virB gene products shown across the top assemble as the T-DNA transfer system. The next three groups of type IV systems, separated by dashed lines, are composed of homologues of some or all of the VirB proteins. The top group corresponds to systems shown to transfer DNA between bacteria, the B. pertussis and H. pylori systems deliver known substrates (PT and CagA respectively) to mammalian cells, and the third group corresponds to systems whose substrates are presently unknown but are postulated to be effector proteins. The symbol (?) denotes the absence of sequence information in the database for other virB genes in these bacteria. The L. pneumophila dot/icm gene products shown across the bottom are homologues of the Shigella flexneri Collb-P9 (Incl) transfer proteins. This system can conjugally transfer DNA, but its proposed role in virulence is to export effector proteins.

One type IV machine, the Lvh system of L. pneumophila, functions as a DNA conjugation system but does not contribute to pathogenesis (Segal et al., 1999a). Similarly, Rhizobium etli codes for several genes on a self-transmissible plasmid that are highly related to the A. tumefaciens vir genes, but mutants are unaffected in nodulation or nitrogen fixation (Bittinger et al., 2000). Thus, at least two type IV systems have been identified that are dispensable for the establishment of the bacteria–host interaction. Several other bacteria, pathogenic and non-pathogenic, code for possible type IV systems in their genomes (Christie and Vogel, 2000). It is not yet established whether the VirB homologues identified in these species have a discernible biological activity.

Another type IV system, the dot/icm system of L. pneumophila, is required for virulence but is only very distantly related to the A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system. Instead, the dot/icm gene products are close homologues of the Tra proteins from the Incl Collb and R64 plasmids. As shown in Fig. 2, the related dot/icm and collb genes are similarly aligned, highly suggestive of a common ancestry (Vogel and Isberg, 1999). This discovery suggests that there is probably not a single progenitor secretion system for the type IV pathways. The question of whether type IV pathways with yet other ancestral lineages contribute to infection might be answered by functional studies of chromosomal gene clusters bearing a conjugation-like signature.

Type IV substrates and cellular consequences of effector protein delivery

Type IV transfer systems can affect the eukaryotic host cell physiology in profoundly different ways (Fig. 1). The type IV system of A. tumefaciens delivers oncogenic T-DNA and effector proteins to plant cells, leading to disruption in the levels of plant growth hormones. This hormone imbalance ultimately results in the formation of characteristic neoplasias at infection sites. The known effector proteins, VirD2, VirE2 and VirF, contribute to virulence in various ways. The function of VirF is not clear, but recent work has defined roles for VirD2 and VirE2 in the infection process. VirD2 is a relaxase required in the bacterium for nicking at the T-DNA border repeat sequences. Upon nicking, VirD2 remains covalently associated with a single-stranded copy of the T-DNA (T-strand) destined for transfer, and it is thought to guide the T-strand across the bacterial envelope (Christie, 1997). VirE2 is a single-stranded (ss) DNA-binding protein (SSB) transferred to plant cells independently of the VirD2 T-strand particle (see below). Once VirE2 enters the plant cell, it binds co-operatively to the VirD2 T-strand particle, forming the so-called T-complex (VirD2 T-strand–VirE2). VirE2 and VirD2 then mediate the delivery of the T-strand to the plant nucleus by virtue of nuclear localization sequences. These proteins might also contribute to T-DNA integration, although host factors also seem to be required at this step (Zhu et al., 2000).

In addition to its nuclear targeting function, recent work suggests that VirE2 might play a second role in the infection process. Intriguingly, VirE2 was shown to form channels in artificial membranes (Dumas et al., 2001). The channels are voltage gated and can transfer ssDNA through membranes. On the basis of this finding, VirE2 was proposed to assemble as the receptor/pore at the plant plasma membrane for docking of the T-DNA transfer system and translocation of the incoming VirD2 T-strand, VirE2 and VirF substrates (Dumas et al., 2001). One assumption of this model is that the assembly of the VirE2 channel at the plant membrane precedes type IV-mediated translocation. Interestingly, another recent report supplied evidence for the virB-independent export of low levels of VirE2, VirD2 and VirF proteins to the extracellular milieu (Chen et al., 2000). This possible alternative export pathway might be used for the initial delivery of a VirE2 receptor/channel to the plant cell membrane. The beauty of this model is that it could account for the extreme broad host range of the T-DNA transfer system – A. tumefaciens exports its own receptor/translocation channel to target cells. Indeed, compelling evidence has now been presented even for A. tumefaciens-mediated DNA transfer to human cells (Kunik et al., 2001).

The effector proteins and some of the cellular consequences of type IV transfer have been determined for two mammalian pathogens, H. pylori and B. pertussis. H. pylori induces signal transduction pathways that result in tyrosine phosphorylation of host proteins adjacent to the site of infection. Last year, H. pylori type I strains carrying the cag pathogenicity island (PAI) were shown to code for a type IV system that directs the transfer of the 145 kDa CagA protein to mammalian cells. Upon transfer, CagA undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation (Segal et al., 1999b; Odenbreit et al., 2000; Stein et al., 2000). Correlated with CagA transfer are a number of changes in host cell physiology. Intriguingly, a percentage of the H. pylori cells attached to the host cell surface were found to associate with a high concentration of CagA proteins often configured as a cylindrical structure (Segal et al., 1999b). These structures were associated with regions of active actin reorganization, suggesting that CagA cylinders might direct host cytoskeletal rearrangements. CagA transfer is also correlated with effacement of microvilli, cup/pedestal formation, interleukin (IL)-8 production and changes in the phosphorylation state of host proteins (Crabtree et al., 1999; Segal et al., 1999b; Odenbreit et al., 2000; Stein et al., 2000). Of considerable interest, tyrosine phosphorylation and the observed changes in host physiology are reminiscent of features ascribed to the Tir protein of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli upon its delivery to mammalian cells by a type III secretion machine (Segal et al., 1999b). H. pylori was also recently shown to inhibit the phagocytic function of monocytes and polymorphonuclear lymphocytes. This antiphagocytic phenotype was dependent on type IV components, including CagT and HPO525, homologues of VirB7 and VirB11 respectively (Ramarao et al., 2000). Thus, CagA, another exported effector, or a surface feature of the cag type IV system appears to contribute to immune evasion.

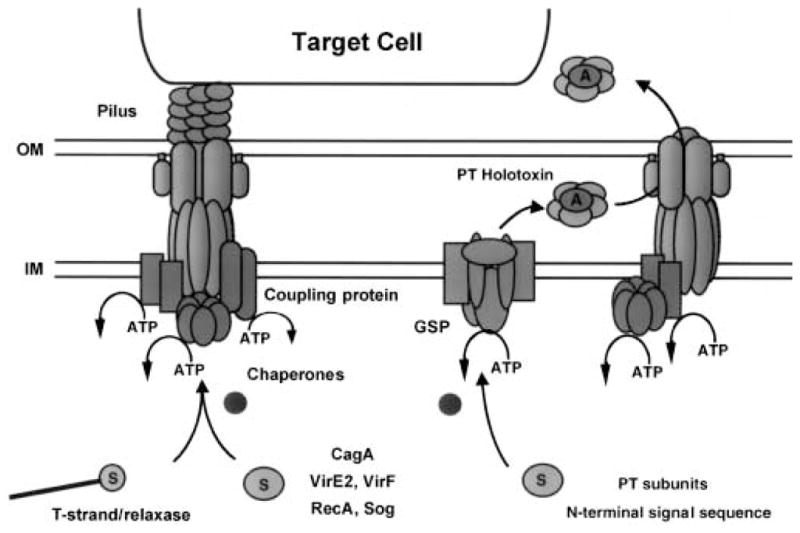

As depicted in Fig. 3, B. pertussis uses a type IV system as a secretion machine (Burns, 1999; Craig-Mylius and Weiss, 1999). PT is a multisubunit toxin of the A/B family and is composed of five subunits, S1–S5. The S1 subunit, or A domain, shares active-site ADP-ribosylating activity and structure with diphtheria toxin (DT), cholera toxin (CT) and other A/B toxins. The B domain is a pentamer of the remaining S2–S5 subunits in a ratio of 1:1:2:1 respectively. The PT subunits are secreted across the cytoplasmic membrane by the general secretory pathway. Assembly of holotoxin in the periplasm is required for recognition and export across the outer membrane by the Ptl system (Farizo et al., 2000). Upon export, the B domain, a ring-shaped oligomer, interacts with host cell glycoprotein receptors and mediates translocation of the A domain across the host cell membrane. In the cytosol, PT ADP ribosylates the α-subunits of G proteins, thus interfering with receptor-mediated activation and associated signalling pathways (Burns, 1999).

Fig. 3.

The known type IV systems differ with respect to the route of substrate translocation. The A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system and the H. pylori CagA system are thought to export substrates in one step across the membrane directly to the eukaryotic cytosol. The B. pertussis Ptl system is thought to export PT in two steps across the cell envelope to the extracellular milieu. Secreted holotoxin then binds to the mammalian cell membrane. See text for additional details.

The type IV dot/icm system is postulated to contribute to L. pneumophila survival within host macrophages. Upon contact with macrophages, L. pneumophila induces pore formation and enters a vacuole. Phagosomes containing L. pneumophila mature into specialized organelles that evade fusion with endosomes and lysosomes. The dot/icm system is implicated in controlling phagosome trafficking, thus creating a niche for intracellular survival. The dot/icm system is thought to export an effector(s) that affects an early stage in phagosome maturation. So far, one substrate of the dot/icm system that is probably not relevant to the infection process has been identified. Reminiscent of dedicated conjugation systems that are capable of transferring unrelated, mobilizable plasmids, the dot/icm system can conjugally transfer the IncQ plasmid RSF1010 to L. pneumophila recipients (Vogel and Isberg, 1999).

No other type IV substrates have been reported at this time. Clearly, an enormously important goal of ongoing investigations is to identify these effectors and the mechanism by which type IV machines promote intracellular survival of Legionella, Brucella, Bartonella and Rickettsia species. Another major objective is to define how the type IV machines are regulated in a pathogenic setting. For the more mechanistic questions of these machines, the structure–function studies of the more tractable conjugation systems are a fitting guide. Current information on these systems is summarized below.

Substrate transfer by dedicated conjugation systems

The bacterial conjugation system is best viewed as a multifunctional machine, composed of proteins or protein subcomplexes dedicated to several distinct activities: (i) substrate processing (the relaxosome); (ii) substrate docking (coupling proteins/chaperones); (iii) translocation (mating channel); and (iv) cell–cell attachment (pilus/adhesins) (Table 1). The processing reaction was once thought to liberate a naked ssDNA molecule for transfer, but recent work has shown this reaction to produce a nucleoprotein particle. This particle minimally consists of a single-stranded form of the plasmid that is covalently attached to a protein termed the relaxase. The relaxase is a component of the relaxosome, a protein complex shown over 30 years ago to cleave the DNA strand destined for transfer (T-strand) at the plasmid origin of transfer (oriT) sequence. Upon cleavage, the relaxase remains attached via a phosphodiester bond to the 5′ end of the T-strand. As mentioned above for VirD2, this covalent linkage, together with an observed 5′–3′ polarity of DNA transfer during conjugation, suggests that the relaxase might supply the requisite substrate recognition signals and piloting functions for T-strand translocation.

Table 1.

Properties and interactions of T-DNA transfer system proteins and their homologuesa.

| Proposed functions | Location | Properties/interactions | Related proteins and properties | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate presentation | ||||

| VirD4 coupling protein | Integral IM | Putative ATPase; required for T-strand/VirD2 and VirE2 export, not for T-pilus assembly; relaxosome specificity | RP4 TraG R388 TrwB F TraD H. pyl. Orf10 |

pBHR1 Mob interaction ATP and DNA binding, ring formation TraD–TraI, TraD–TraM DNA binding Affects IL-8 synthesis in gastric epithelial cells |

| VirE1 chaperone | Cytoplasmic | Required for VirE2 export, stabilizes VirE2, interacts with internal domain of VirE2 | ||

| VirC1/VirC2 | IM | Required for VirD2-T-strand export, VirC1 related to ParA proteins | ||

| Translocation | ||||

| Energetics | ||||

| VirB4 | Integral IM | ATPase; self-assembles, role in substrate export | F TraC | Mutants affected in pilus formation and membrane interaction |

| VirB11 | Peripheral IM | ATPase; self-assembles via N- and C-terminal domains; interacts with other VirB proteins; possible chaperone/morphogenetic function |

H. pyl. CagE RP4 TrbB, H. pylori HP0525, and R388TrwD RP4 |

IL-8 induction ATPases Form hexameric rings in solution HP0525 crystal structure Proposed GroEL-like chaperones Reduction in intracellular ATP levels causes disassembly of transfer complex |

| Mating channel | ||||

| VirB1 | IM, PP, OM | Putative transglycosylase, contributes to channel assembly | F orf169 | Not required for transfer |

| VirB6 | Polytopic IM | Evidence for stabilization of VirB3, VirB5 and other VirB proteins; possible IM pore component | ||

| VirB7 | OM | Lipoprotein, VirB7–VirB7, VirB7–VirB9 interactions VirB7–VirB9 heterodimer stabilizes other VirB proteins |

B. pert. Ptll | Dimerizes with PtlF |

| VirB8 | IM | Assembly factor important for positioning of VirB9 and VirB10; VirB8–VirB9, VirB8–VirB10 interactions | ||

| VirB9 | OM | VirB7–VirB9 stabilizing activity, VirB9–VirB8, VirB9–VirB9, VirB9–VirB10 interactions | B. pert. PtlF | Dimerizes with Ptll |

| VirB10 | Bitopic IM | Links IM to OM VirB7–VirB9 complex, VirB10–VirB10, VirB10–VirB9, VirB10–VirB9 interactions | RP4 RP4 F |

Transfer components fractionate with vesicles intermediate in density between those of IM and OM Extended (200 nm) conjugative junctions Extended conjugative junctions |

| Attachment | ||||

| VirB1* | Exocellular | C-terminal 73-residue processed form of VirB1, VirB1*–VirB9, adhesion. Contributes to T-pilus formation | ||

| VirB2 | IM, OM, Exocellular | Pilin, processed by SPI (?) from 12 to 7 kDa, cyclizes via N–C peptide bond | RP4 TrbC F TraA F TraN |

Processed by SPI, TraF and an unknown factor, N–C cyclization Processed by SPI and TraQ, N-acetylated by TraX Receptor specificity, adhesin? |

| VirB3 | OM | Stabilized by VirB4, VirB6 | ||

| VirB5 | IM, PP, OM, Exocellular | Stabilized by VirB6; possible chaperone Minor pilin subunit |

||

Citations for information presented in this table are in the text.

In addition to the T-strand/relaxase substrate, it is now firmly established that conjugation machines also transfer proteins that are non-covalently associated with ssDNA. The list of transferred proteins includes the Sog primase by plasmid Collb-P9 (Rees and Wilkins, 1990), RecA by the F and RP4 plasmid transfer systems (Heinemann, 1999) and VirE2 SSB and VirF proteins by the T-DNA transfer system (Vergunst et al., 2000). A recent extension of work on Sog transfer showed that the Collb conjugation system can transfer Sog proteins to recipient cells even when the plasmid was rendered non-transmissible. The screen for protein transfer relied on the ability of Sog primase to substitute for DnaG primase of E. coli in the replication of the bacterial chromosome. Complementation of the dnaG defect was detected in mating mixtures, required synthesis of the Collb sex pilus in the donor cell and was blocked by the presence of a Collb entry exclusion function in the recipient cell (Wilkins and Thomas, 2000).

Early work with mixed infection experiments showed that A. tumefaciens T-DNA deletion mutants are capable of transferring the VirE2 SSB and VirF proteins independently of the T-strand–VirD2 complex (see Christie, 1997). Very recently, exciting new evidence was presented for VirE2 and VirF transfer to plants. In this study, both proteins were fused to the Cre recombinase from bacteriophage P1, and transfer from A. tumefaciens to Arabidopsis was demonstrated by Cre-mediated recombination at lox target sites present in the plant nuclear genome. Confirming previous work, the virB- and virD4- encoded type IV system was shown to be required for translocation of both proteins into the plant cell (Vergunst et al., 2000).

Coupling proteins and chaperones

Two types of factors, coupling proteins and chaperones, appear to be necessary for presentation of DNA and protein substrates to the mating channel. The coupling proteins are thought to link the DNA transfer intermediate to the mating channel. These are generally referred to as the TraG protein family, with members including TraG (RP4 and Ti plasmids), TrwB (R388), TraD (F) and VirD4 of the T-DNA transfer system (Fig. 2). These proteins are not required for relaxosome formation or oriT nicking, pilus production or channel-dependent bacteriophage sensitivity (see Lai et al., 2000). Instead, they possess a number of properties consistent with a coupling function. Physical features include an N-terminal transmembrane domain and a large C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (Das and Xie, 1998; Lee et al., 1999). Most, but not all, have discernible Walker A and B nucleotide-binding motifs suggestive of an ATPase activity. In addition, R388 TrwB has ATP-binding activity and DNA binding-dependent ring formation, and it stimulates TrwC relaxase activity (Moncalian et al., 1999). Other evidence for interactions between the coupling protein and relaxase components has been presented (Sastre et al., 1998; Szpirer et al., 2000). Finally, quite compelling evidence for a coupling function derives from the construction of chimeric transfer systems composed of a mating channel from one Tra system and a heterologous coupling protein from a different Tra system. Some of these chimeric systems display substrate preferences that reflect the Tra system origin of the coupling protein (Cabezon et al., 1997; Hamilton et al., 2000).

There is accumulating evidence that these coupling proteins contribute not only to DNA transport but also to type IV-mediated protein export. For example, A. tumefaciens virD4 mutants cannot export VirE2 to plant cells (Christie, 1997; Vergunst et al., 2000), and H. pylori HPO524 mutants fail to export CagA to mammalian cells (Covacci et al., 1999). Members of this coupling protein family are present in most type IV systems examined, raising the possibility that these proteins or functionally equivalent proteins serve as general docking factors for type IV substrates (Fig. 1).

Candidates for secretion chaperones in the T-DNA transfer system include the VirC1 and VirC2 proteins required for T-DNA transfer but dispensable for VirE2 export, and VirE1 required for VirE2 export but not for VirD2 T-strand export (Christie, 1997; Zhu et al., 2000). VirC1 associates with the cytoplasmic membrane and binds a sequence termed ‘overdrive’ located next to the T-DNA right border sequence. Interestingly, VirC1 also displays homology to bacterial ParA proteins. One proposal for further study is that the VirC proteins target the relaxosome to the VirD4 coupling protein and some-how configure the VirD2 T-strand for export. In contrast, VirE1 has physical and functional properties reminiscent of the cytoplasmic chaperones required for type III secretion. VirE1 interacts with an internal domain of VirE2 that overlaps regions implicated in VirE2 self-association and DNA binding (Deng et al., 1999; Sundberg and Ream, 1999; Zhou and Christie, 1999). There is some evidence for VirE1 stabilization of VirE2 in vivo and inhibition of VirE2 aggregation in vitro (Deng et al., 1999). Thus, reminiscent of the proposed functions of the substrate-specific chaperones in the flagellar-based (type III) secretion systems, VirE1 might interact with an unfolded form of VirE2 and prevent it from premature interactions in the bacterium.

Type IV transfer ATPases

Three families of putative ATPases are associated with type IV transfer systems. One consists of the TraG family of coupling proteins described above (Table 1). A second is composed of homologues of A. tumefaciens VirB4 protein. These proteins are ubiquitous among the type IV systems and are sometimes present in two or more copies. VirB4 mutants with defects in the Walker A motif are non-functional and exert a dominant-negative phenotype, suggesting that this ATPase functions as an oligomer. Further studies have provided evidence for a transmembrane topology, self-association and a structural contribution to channel formation that is independent of the VirB4 ATPase activity. Based on these properties, this family of ATPases might transduce information, possibly in the form of ATP-induced conformational changes, across the cytoplasmic membrane to extracytoplasmic subunits (Dang et al., 1999).

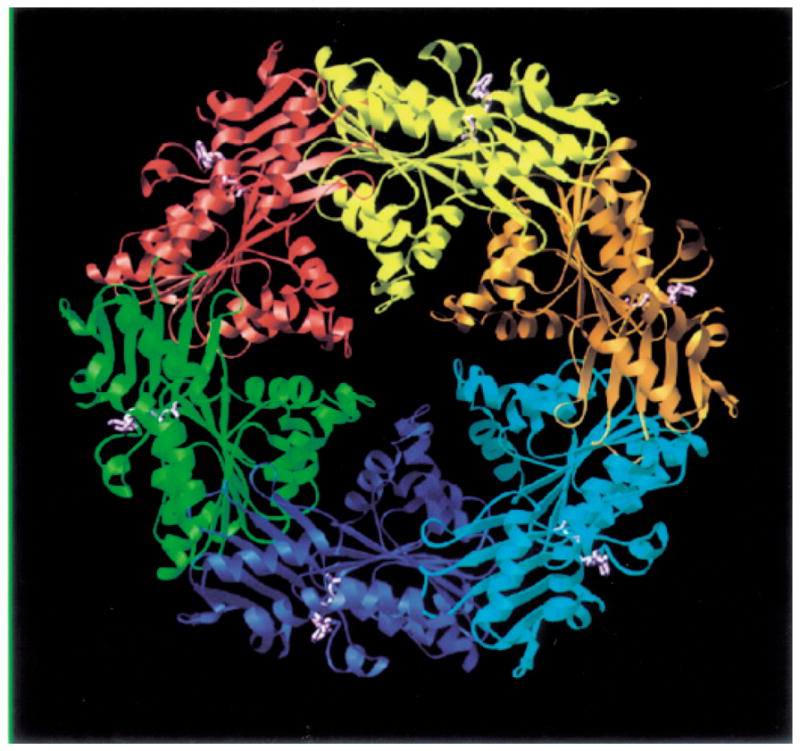

Exciting new progress has led to specific predictions regarding the third family of ATPases, which are homologues of the RP4 TrbB and A. tumefaciens VirB11 proteins. Members of this ATPase family are present among all type II and IV transfer systems so far characterized, and they possess four highly conserved motifs (Rivas et al., 1997). An early study demonstrated ATP hydrolysis activity of purified VirB11 (see Christie, 1997), and more recent work has reported the catalytic activities of TrbB of plasmid RP4, TrwD of plasmid R388 and HPO525 of the H. pylori Cag pathogenicity island (Rivas et al., 1997; Krause et al., 2000a, b). These ATPases generally associate tightly but peripherally with the cytoplasmic membrane, although TrbB of plasmid RP4 is predominantly cytoplasmic. Recent biochemical and genetic studies have supplied evidence for homo-oligomer formation of these ATPases. VirB11 self-association was first suggested by the suppression of dominant mutations by multicopy expression of wild-type virB11. More recent genetic studies supported a prediction that VirB11 self-associates via two domains located in its N- and C-termini. Furthermore, the C-terminal interaction domain functions only in the context of an intact Walker A motif. Thus, ATP binding was predicted to be critical for VirB11 oligomerization (Rashkova et al., 2000).

Satisfyingly, recent structural work has supported the predictions from these genetic studies. The TrbB, TrwD and HPO525 ATPases have been shown by electron microscopy to assemble as homohexameric rings with an ≈ 12 nm diameter and an ≈ 3 nm central region of low electron density (Krause et al., 2000a, b). The rings were stabilized by the addition of ATP, and ATP hydrolysis was also stimulated by the addition of phospholipid, suggesting an interaction with the membrane. Very recently, the crystal structure of a binary complex of H. pylori HP0525 bound to ADP was solved at a resolution of 2.5 A (Fig. 4) (Yeo et al., 2000). Each monomer was shown to consist of two domains formed by the N- and C-terminal halves of HP0525. In the hexamer, the N- and C-terminal domains formed two rings, which together form a chamber open on one side and closed on the other. This structure led to a model in which the VirB11 family of ATPases function as chaperones reminiscent of the GroEL family for translocating unfolded proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane. (Krause et al., 2000b; Yeo et al., 2000). Whether this proposed function is required for substrate translocation and/or biogenesis of the translocase and pilus awaits further study.

Fig. 4.

Crystal structure of H. pylori HP0525 bound to ADP. Each subunit is in ribbon representation colour-coded differently. ADP is in ball-and-stick representation colour-coded in magenta. This figure was kindly provided by G. Waksman (see Yeo et al., 2000).

The mating channel

Although the VirB11-like ATPases and extracellular pili (see below) are increasingly structurally defined, obtaining an architectural view of the mating channel has been considerably more problematic. Conjugative junctions with an estimated mean length of ≈ 200 nm have been shown to form between the outer membranes of aggregates of mating cells carrying plasmid RP4. However, membrane fusions or transenvelope structures that might correspond to mating channels within these conjugative junctions have not been detected, leading to the suggestion that the transfer channel is a subtle anatomical feature (Samuels et al., 2000).

Table 1 summarizes the current information about the protein components of the T-DNA transfer system and homologues in related systems. Although most of this information has been reviewed recently, several intriguing new results need to be highlighted. Many conjugation systems, bacteriophages and flagellar and type III secretion systems encode enzymes with putative murein hydrolase activity. Typically, mutations in the active sites of these proteins perturb phage assembly or macro-molecular transfer efficiencies by 100- to 1000-fold. Interestingly, virB1 mutants of A. tumefaciens accumulate cellular VirB2 pilin but cannot assemble T-pili of sufficient length for detection in exocellular material recovered from sheared cells (Lai et al., 2000). virB1 mutants still transfer T-DNA to plant cells, albeit with reduced efficiencies, raising the question of whether these mutants elaborate a functional, stubby T-pilus or can transfer T-DNA in the complete absence of T-pilus formation. VirB1 from the nopaline plasmid pTiC58 is processed to a 73-residue, C-terminal fragment termed VirB1*. VirB1* localizes exocellularly but is not detected in purified T-pilus preparations. Expression of either the N-terminal trans-glycosylase domain or the C-terminal VirB1* fragment partially complements a non-polar virB1 null mutation, suggesting that both VirB1 domains contribute unique functions to this type IV transfer system (Llosa et al., 2000).

For the A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system, the proposed components of the transfer channel are VirB6, VirB7, VirB8, VirB9 and VirB10 in association with the VirD4 coupling protein and the two VirB ATPases described above. VirB6 is thought to span the inner membrane as many as six times and is presently a candidate component of the channel at the cytoplasmic membrane. VirB6 was recently shown to stabilize two VirB proteins, VirB3 and VirB5, implicated in pilus assembly or function. In addition, both a non-polar virB6 mutation and VirB6 overproduction result in diminished accumulation of other VirB proteins, providing strong evidence for complex formation with other VirB proteins (Hapfelmeier et al., 2000). The VirB7 lipoprotein forms a disulphide cross-linked dimer with itself and with VirB9. The heterodimer has been postulated to function as a nucleation centre for recruitment and stabilization of other VirB proteins during assembly of the T-DNA transfer machine (Christie, 1997). A recent electron microscopy study also indicates that VirB8, an inner membrane protein, contributes to biogenesis of the transfer system (Kumar et al., 2000). In wild-type cells, two VirB proteins, VirB9 and VirB10, were found to assemble at discrete sites on the cell surface. However, in virB8 mutants, these proteins distributed more uniformly around the cell surface. These findings prompted the proposal that VirB8 contributes to the positioning of newly synthesized VirB proteins at the cell surface. In support of this model, the pairwise interactions listed in Table 1 have been demonstrated (see Christie, 1997; Das and Xie, 2000).

The conjugal pilus

Conjugation systems elaborate several morphologically distinct pili (Ippen-Ihler and Maneewannakul, 1991). The F-like plasmids synthesize long flexible pili of ≈ 8 nm in diameter that mediate efficient plasmid transfer in liquid and solid media (the universal mating type). Plasmids of the IncP, IncN, IncW and Rh1 incompatibility groups and the A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system elaborate more rigid pili that mediate DNA transfer efficiently on solid media but poorly in liquid media. The Incl plasmids synthesize two pili, a thick rigid pilus required for conjugation both in liquid and on a solid surface and a thin, flexible pilus required for mating in liquid. The F pilus is depicted as a dynamic structure that mediates attachment to specific receptors on the recipient cell surface and retracts to bring donor and recipient cells into direct physical contact (Fig. 1). In contrast, the rigid pili of the IncP, N, W, Rh1 and I plasmid and T-DNA transfer systems are often detached from the cell and tend to aggregate in bundles (Ippen-Ihler and Maneewannakul, 1991; Lai and Kado, 2000). Thus, instead of a retraction mechanism for establishing mating contacts, these pili probably mediate cellular aggregation through non-specific hydrophobic interactions.

The RP4 and the T-DNA transfer systems deliver DNA to yeast efficiently and, as reviewed elsewhere, the T-DNA transfer system delivers DNA to a wide range of other eukaryotic cell types (Bates et al., 1998; Christie and Vogel, 2000). Pilus formation is important for interkingdom DNA transfer. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the conjugative pili of these systems minimally mediate attachment to the eukaryotic target cells. The L. pneumophila dot/icm system is ancestrally related to the Tra system of the Incl Collb-P9 plasmid that assembles the thick rigid pilus. Fibrous structures containing dotH and dotO have been visualized on the surfaces of L. pneumophila cells incubated with macrophages or macrophage-conditioned media (Watarai et al., 2000). These structures might correspond functionally to the thick pili of the Incl plasmids.

The pilin proteins of the type IV systems are homologous to one another and display a number of common physical properties. Typically, these proteins are synthesized as proproteins with an unusually long signal peptide of 25–50 residues (Eisenbrandt et al., 1999; Lai and Kado, 2000). Processing to mature pilin requires the action of cellular factors and often one or more Tra proteins (Table 1). For example, the insertion of the TraA propilin of F into the cytoplasmic membrane requires TraQ protein. The chromosomally encoded LepB peptidase then cleaves the signal sequence, and another F-encoded protein, TraX, N-acetylates the N-terminus of TraA to yield mature pilin. Both the TrbC pilin of plasmid RP4 and the VirB2 pilin of the T-DNA transfer system undergo a novel maturation pathway. Signal sequences from both proteins are removed, presumably by LepB, and the C-terminus of RP4 is further processed by chromosomal and plasmid-borne proteases. Of considerable interest, VirB2 and TrbC then undergo a cyclization reaction that is novel to bacteria, resulting in the formation of an intramolecular covalent head-to-tail peptide bond (Eisenbrandt et al., 1999). A recent study showed that RP4 TraF protein catalyses both a C-terminal processing reaction and TrbC cyclization; moreover, mutational analyses established a correlation between pilin cyclization and pilus elaboration, conjugal DNA transfer and bacteriophage sensitivity (Eisenbrandt et al., 2000).

Mature pilin is thought to localize initially at the inner membrane, where, upon an unknown signal, it is recruited for pilus assembly. There are at least two lines of evidence suggesting that the pilin monomer also plays a more direct role in substrate trafficking. Recent ultra-structural work has shown that the RP4 mutants defective in pilin synthesis still form conjugative junctions that are indistinguishable from those established by wild-type cells (Samuels et al., 2000). Intriguingly, these cells fail to transfer DNA. Thus, the pilin might in fact be a structural component of the transfer machine. Secondly, a recent study showed that each of the B. pertussis Ptl proteins, including the PtlA pilin homologue (Fig. 2), is needed for efficient PT secretion (Craig-Mylius and Weiss, 1999). No ptl-encoded pilus has yet been visualized, consistent with a more direct role for pilin in PT secretion. Finally, it is intriguing that A. tumefaciens virB1 mutants fail to assemble detectable T-pili yet are still able to transfer T-DNA to plant cells. Perhaps in these mutants, the cellular form of VirB2 pilin assembles with other VirB proteins to form a functional channel, whereas an alternative attachment mechanism compensates for the absence of the T-pilus.

Concluding remarks

Recent studies have identified several potential mechanistic parallels between type IV systems and other bacterial secretion pathways. First, there is now compelling evidence for the contribution of an ATP-dependent chaperone for substrate presentation and/or biogenesis of the type IV transfer channel and pilus. The structural resolution of HP0525 represents a major advance, and similarities between the double hexameric ring of HPO525 and GroEL-type chaperones lead to strong predictions of a chaperone activity for members of the VirB11 family. VirB11 homologues are present in many species of bacteria and archaebacteria, as components of type II secretion machines and other fimbrial biogenesis and competence systems, suggesting that this proposed chaperone activity is extremely widely distributed. Secondly, the ATP-independent VirE1 chaperone bears physical and functional similarities to the type III secretion chaperones (Plano et al., 2001). As is true for the secretion of most effectors via the type III pathway, a VirE1-like chaperone might be generally required for type IV-mediated protein export. Thirdly, although the coupling proteins have been postulated to correspond to a docking site for type IV transfer intermediates, in fact their transmembrane topologies, putative ATPase activities, ring formation and demonstrated substrate interactions are highly suggestive of a role as a translocase for driving secretion across the cytoplasmic membrane. The extent that this (or another virB-encoded) translocase functions like other known translocases remains to be examined. Fourthly, although the architecture of the type IV transfer channel is still undefined, it is nevertheless intriguing to note that the stabilizing activities of small, outer membrane lipoproteins such as VirB7 have been shown to contribute to the biogenesis of the type IV T-DNA and PT transfer systems, as well as to unrelated surface structures, including curli, bundle-forming pili and flagella (Christie, 1997). Finally, the proposed channel activity of VirE2 is highly reminiscent of the pore-forming activities of the B. pertussis pertussis toxin B pentamer for translocation of the A domain (Burns, 1999) and of the B/D proteins associated with translocation of type III substrates. VirE2 might also possess receptor activity reminiscent of Tir protein for type III secretion by enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) (Plano et al., 2001). Other type IV systems, including the L. pneumophila dot/icm system (Vogel and Isberg, 1999) and the H. pylori Cag system (Segal et al., 1999b), have also been proposed to encode pore-forming and Tir-like activities respectively.

In sum, the type IV systems are intrinsically fascinating secretion machines by virtue of their capacity to move DNA–protein complexes, multisubunit toxins and monomeric proteins across the Gram-negative cell envelope. Further definition of the mechanistic themes and variations of type IV translocation are, and should remain, focused on the model conjugation and T-DNA transfer systems. However, the type IV systems are also fascinating subjects for study by virtue of their demonstrated contributions to the infection processes of several medically relevant pathogens. The intensive efforts being applied to the identification of effector molecules and the definition of the cellular consequences of type IV translocation promise to yield fundamental new information about signal transduction pathways activated during the course of infection.

Acknowledgments

I thank Vitaly Citovsky, Barbara Hohn, Ralph Isberg, Brian Wilkins and Gabriel Waksman for communication of results prior to publication.

Restrictions in the numbers of allowable references have prevented me from citing numerous important contributions to the fields of conjugation, Agrobacterium biology and pathogenesis of the organisms discussed. I am especially grateful to Gabriel Waksman for providing the ribbon representation of the HP0525 crystal structure. I apologize to the authors whose manuscripts were not referenced. I refer readers to other recent reviews for additional information and reference lists. Work in my laboratory is supported by NIH grant GM48746.

References

- Bacon DJ, Alm RA, Burr DH, Hu L, Kopecko DJ, Ewing CP, et al. Involvement of a plasmid in virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81–176. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4384–4390. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4384-4390.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates S, Cashmore AM, Wilkins BM. IncP plasmids are unusually effective in mediating conjugation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6538–6543. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6538-6543.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittinger MA, Gross JA, Widom J, Clardy J, Handelsman J. Rhizobium etli CE3 carries vir gene homologs on a self-transmissible plasmid. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 2000;13:1019–1021. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DL. Biochemistry of type IV secretion. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezon E, Sastre JI, de la Cruz F. Genetic evidence of a coupling role for the TraG protein family in bacterial conjugation. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:400–406. doi: 10.1007/s004380050432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Li CM, Nester EW. Transferred DNA (T-DNA) -associated proteins of Agrobacterium tumefaciens are exported independently of virB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7545–7550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120156997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie PJ. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-complex transport apparatus: a paradigm for a new family of multifunctional transporters in eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3085–3094. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3085-3094.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie PJ, Vogel JP. Bacterial type IV secretion: conjugation systems adapted to deliver effector molecules to host cells. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covacci A, Telford JL, Del Giudice G, Parsonnet J, Rappuoli R. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science. 1999;284:1328–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree JE, Kersulyte D, Li SD, Lindley IJ, Berg DE. Modulation of Helicobacter pylori induced interleukin-8 synthesis in gastric epithelial cells mediated by cag PAI encoded VirD4 homologue. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:653–657. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.9.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Mylius KA, Weiss AA. Mutants in the ptlA–H genes of Bordetella pertussis are deficient for pertussis toxin secretion. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;179:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang TA, Zhou XR, Graf B, Christie PJ. Dimerization of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB4 ATPase and the effect of ATP-binding cassette mutations on the assembly and function of the T-DNA transporter. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1239–1253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Xie YH. Construction of transposon Tn3phoA: its application in defining the membrane topology of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens DNA transfer proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:405–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Xie YH. The Agrobacterium T-DNA transport pore proteins VirB8, VirB9, and VirB10 interact with one another. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:758–763. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.758-763.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Chen L, Peng WT, Liang X, Sekiguchi S, Gordon MP, et al. VirE1 is a specific molecular chaperone for the exported single-stranded-DNA-binding protein VirE2 in Agrobacterium. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1795–1807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas F, Duckely M, Pelczar P, van Gelder P, Hohn B. An Agrobacterium VirE2 channel for T-DNA transport into plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001 doi: 10.1073/pnas.011477898. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbrandt R, Kalkum M, Lai EM, Lurz R, Kado CI, Lanka E. Conjugative pili of IncP plasmids, and the Ti plasmid T pilus are composed of cyclic subunits. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22548–22555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbrandt R, Kalkum M, Lurz R, Lanka E. Maturation of IncP pilin precursors resembles the catalytic dyad-like mechanism of leader peptidases. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6751–6761. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6751-6761.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farizo KM, Huang T, Burns DL. Importance of holotoxin assembly in Ptl-mediated secretion of pertussis toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4049–4054. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4049-4054.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulongne V, Bourg G, Cazevieille C, Michaux-Charachon S, O’Callaghan D. Identification of Brucella suis genes affecting intracellular survival in an in vitro human macrophage infection model by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1297–1303. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1297-1303.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Lee H, Li PL, Cook DM, Piper KR, Beck von Bodman S, et al. TraG from RP4 and TraG and VirD4 from Ti plasmids confer relaxosome specificity to the conjugal transfer system of pTiC58. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1541–1548. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1541-1548.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapfelmeier S, Domke N, Zambryski PC, Baron C. VirB6 is required for stabilization of VirB5 and VirB3 and formation of VirB7 homodimers in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4505–4511. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4505-4511.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann J. Genetic evidence of protein transfer during bacterial conjugation. Plasmid. 1999;41:240–247. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong PC, Tsolis RM, Ficht TA. Identification of genes required for chronic persistence of Brucella abortus in mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4102–4107. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4102-4107.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippen-Ihler K, Maneewannakul S. Conjugation among enteric bacteria: mating systems dependent on expression of pili. In: Dworkin M, editor. Microbial Cell–Cell Interactions. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 1991. pp. 35–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob-Dubuisson F, Locht C, Antoine R. Two-partner secretion in Gram-negative bacteria: a thrifty, specific pathway for large virulence proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:306–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S, Barcena M, Pansegrau W, Lurz R, Carazo J, Lanka E. Sequence related protein export NTPases encoded by the conjugative transfer region of RP4 and by the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori share similar hexameric ring structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000a;97:3067–3072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050578697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S, Pansegrau W, Lurz R, de la Cruz F, Lanka E. Enzymology of type IV macromolecule secretion systems: the conjugative transfer regions of plasmids RP4 and R388 and the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori encode structurally and functionally related nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases. J Bacteriol. 2000b;182:2761–2770. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2761-2770.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RB, Xie YH, Das A. Subcellular localization of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA transport pore proteins: VirB8 is essential for the assembly of the transport pore. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:608–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunik T, Tzfira T, Kapulnik Y, Gafni Y, Dingwall C, Citovsky V. Genetic transformation of HeLa cells by Agrobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001 doi: 10.1073/pnas.041327598. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EM, Kado CI. The T-pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EM, Chesnokova O, Banta LM, Kado CI. Genetic and environmental factors affecting T-pilin export and T-pilus biogenesis in relation to flagellation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3705–3716. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.13.3705-3716.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Kosuk N, Bailey J, Traxler B, Manoil C. Analysis of F factor TraD membrane topology by use of gene fusions and trypsin-sensitive insertions. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6108–6113. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6108-6113.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton KJ, Higgins CF. The Escherichia coli ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:5–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llosa M, Zupan J, Baron C, Zambryski P. The N- and C-terminal portions of the Agrobacterium VirB1 protein independently enhance tumorigenesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3437–3445. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3437-3445.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncalian G, Cabezon E, Alkorta I, Valle M, Moro F, Valpuesta JM, et al. Characterization of ATP and DNA binding activities of TrwB, the coupling protein essential in plasmid R388 conjugation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36117–36124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschiroli ML, Bourg G, Foulongne V, et al. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1210–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Puis J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmalayam I, Karem K, Baumstark B, Massung R. The gene encoding the 17-kDa antigen of Bartonella henselae is located within a cluster of genes homologous to the virB virulence operon. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:377–382. doi: 10.1089/10445490050043344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plano GV, Day JB, Ferracci F. Type III export: new uses for an old pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:284–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramarao N, Gray-Owen SD, Backert S, Meyer TF. Helicobacter pylori inhibits phagocytosis by professional phagocytes involving type IV secretion components. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1389–1404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashkova S, Zhou XR, Christie PJ. Self-assembly of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB11 traffic ATPase. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4137–4145. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4137-4145.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees CED, Wilkins BM. Protein transfer into the recipient cell during bacterial conjugation: studies with F and RP4. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1199–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas S, Bolland S, Cabezon E, Goni FM, de la Cruz F. TrwD, a protein encoded by the IncW plasmid R388, displays an ATP hydrolase activity essential for bacterial conjugation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25583–25590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond GPC. Secretion of extracellular virulence factors by plant pathogenic bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels AL, Lanka E, Davies JE. Conjugative junctions in RP4-mediated mating of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2709–2715. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2709-2715.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkvist M. Biology of type II secretion. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre JI, Cabezon E, de la Cruz F. The carboxyl terminus of protein TraD adds specificity and efficiency to F-plasmid conjugative transfer. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6039–6042. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.6039-6042.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiederer M, Anderson B. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of three Bartonella henselae genes homologous to the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB region. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:141–147. doi: 10.1089/104454900314528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal G, Russo JJ, Shuman HA. Relationships between a new type IV secretion system and the icm/dot virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 1999a;34:799–809. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins L. Altered states: Involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999b;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieira R, Comerci DJ, Sanchez DO, Ugalde RA. A homologue of an operon required for DNA transfer in Agrobacterium is required in Brucella abortus for virulence and intracellular multiplication. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4849–4855. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4849-4855.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg CD, Ream W. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens chaperone-like protein, VirE1, interacts with VirE2 at domains required for single-stranded DNA binding and cooperative interaction. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6850–6855. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6850-6855.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpirer CY, Faelen M, Couturier M. Interaction between the RP4 coupling protein TraG and the pBHR1 mobilization protein Mob. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1283–1292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergunst AC, Schrammeijer B, den Dulk-Ras A, de Vlaam CM, Regensburg-Tuink TJ, Hooykaas PJ. VirB/D4-dependent protein translocation from Agrobacterium into plant cells. Science. 2000;290:979–982. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel JP, Isberg RR. Cell biology of Legionella pneumophila. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:30–34. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watarai M, Andrews HL, Isberg RR. Formation of a fibrous structure on the surface of Legionella pneumophila associated with exposure of DotH and DotO proteins after intracellular growth. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:313–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BM, Thomas AT. DNA-independent transport of plasmid primase protein between bacteria by the l1 conjugation system. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:650–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo HJ, Savvides SN, Herr AB, Lanka E, Waksman G. Crystal structure of the hexameric traffic ATPase of the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1461–1472. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XR, Christie PJ. Mutagenesis of Agrobacterium VirE2 single-stranded DNA-binding protein identifies regions required for self-association and interaction with VirE1 and a permissive site for hybrid protein construction. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4342–4352. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4342-4352.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Oger PM, Schrammeijer B, Hooykaas PJ, Farrand SK, Winans SC. The bases of crown gall tumorigenesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3885–3895. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.3885-3895.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]