Abstract

An herb derived compound, levo-tetrahydropalmatine (L-THP), attenuates self-administration of cocaine and opiates in rodents. Since L-THP mainly antagonizes dopamine D2 receptors (D2R) in the brain, it is likely to regulate other addictive behaviors as well. Here, we examined whether L-THP regulates ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice using a two-bottle choice drinking experiment. L-THP treated mice consumed less ethanol compared to vehicle-treated mice during the 15% ethanol drinking session while water consumption remained similar between each group. We then examined the molecular basis underlying the pharmacological effect of L-THP in mice. Our results indicated that a single injection L-THP increased active phosphorylated forms of PKA, AKT and ERK in the caudate-putamen (CPu), but not in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), of alcohol naïve mice. Interestingly, we found that systematic treatment with L-THP for 4 consecutive days while mice were drinking 15% ethanol increased pPKA levels in the CPu, but not in the NAc. In contrast to the effect of acute L-THP treatment, no differences were detected for pAKT or pERK in either striatal regions. Together, our findings suggest that reduction of ethanol drinking by L-THP treatment is possibly correlated with D2R-mediated PKA signaling in the CPu.

Keywords: L-THP, ethanol drinking, dopamine D2 receptor, striatum

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) lead to devastating consequences including social and economic problems but only have limited treatment options [1]. Thus far, pharmacological agents for the management of AUD have mainly focused on the glutamatergic and opioidergic systems. Although specific inhibition of the dopaminergic system has failed to result in the development of pharmacological agents to treat addictive behaviors because of undesirable side effects, indirect or partial inhibition of dopamine receptors, especially dopamine D2 receptors (D2R), has shown promise for the treatment of addiction to other drugs of abuse [2].

Levo-tetrahydropalmatine (L-THP) has been identified as the active compound of the plant species Stephania ambigua and Corydalis teranda, which have been used as natural sedative and analgesic agents in China [3]. Besides the potent antinociceptive effect of L-THP, it reduces cocaine and morphine seeking behaviors in rodents [4-6]. Interestingly, L-THP appears to inhibit dopamine receptors, especially D2R although it interacts with other receptors [7]. The blockade of D2Rs triggers the disinhibition of adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity as it is coupled to Gi/Go proteins while inhibition of dopamine D1Rs has the opposite function via Gs/Golf in the brain. Dopamine is mainly released to the striatum from axon terminals of dopaminergic neurons projecting from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) [8]. The striatum mediates some of the addictive properties of drug abuse as it is involved in the control of motivation, goal-oriented and habitual behaviors [9].

Although L-THP is known to attenuate addictive phenotypes in cocaine and morphine abuse [6, 10], it remains unclear whether L-THP can alter ethanol consumption in mice. Here, we examined the pharmacological effect of L-THP on ethanol drinking and a possible signaling pathway that could mediate its effect in mice. Our findings provide a novel role of L-THP in reducing ethanol consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Only 8-12 week old male mice were used in all experiments of this study. All mice used in the experiments were grouped (5 mice per group) with the exception of the group that was individually housed during the 2-bottle choice experiment. Mice were housed in standard Plexiglas cages with food and water available ad libitum. The colony room was maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 6:00 a.m. Experimental and animal care procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in accordance with NIH guidelines.

2.2. Drugs

L-THP was dissolved in DMSO (final concentration 1%, v/v) followed by dilution in 23% (w/v) (2-hydroxypropyl)-beta-cyclodextrin in saline. Vehicle-treated mice received 1% (v/v) DMSO/ 23% (w/v) (2-hydroxypropyl)-beta-cyclodextrin in saline during the experiments. The dose of L-THP used in the experiments was found to alter behavior in vivo with no detectable neurotoxicity. In order to investigate whether the effect of L-THP on PKA activity was mostly mediated by D2Rs, Bromocriptine (Tocris Biosciences, Ellisville, Missouri) was pretreated via intraperitoneal injection 15 minutes before the L-THP injection. Bromocriptine was dissolved in DMSO and diluted in saline (final concentration 1%, v/v). All compounds, unless otherwise specified, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.3. Two-Bottle Choice Drinking

To assess the effect of L-THP on alcohol intake and preference, two-bottle choice drinking was employed in which individually housed mice were allowed 24-hour-access to two identical 50 ml sipper tubes containing water and 3% ethanol (v/v) for four consecutive days. To generate a drinking profile in response to increasing ethanol doses, the concentration of alcohol was increased from 3%, to 6%, then to 10% and then to 15% with 4 days of access at each concentration. The weights of bottles in two empty cages (without mice) were measured throughout the experiment and the volume lost attributable to bottle shacking and evaporation was subtracted from the drinking bottles for each mice. Two-bottle choice drinking was used to measure preference and consumption of ethanol in each treatment group of mice (n = 12/group) as previously described with minor modifications [11, 12]. Voluntary ethanol consumption was measured and the positions of the bottles were changed to exclude position preference every two days. Three doses of L-THP were used (2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg). During the 15% ethanol drinking session, L-THP was administered once per day for 4 consecutive days. In order to have an accurate measure of ethanol consumption, grams of ethanol consumed per kilogram of body weight per day were calculated for each mouse across the two-bottle choice drinking. A relative ethanol preference was used as ethanol preference ratios that were calculated at each ethanol concentration by dividing the total consumed ethanol solution by the total consumed fluid (ethanol plus water) solution. One week after the two-bottle choice drinking experiment, the same mice were tested for taste preference to determine whether treatment of L-THP might affect preference for saccharin (sweet) or quinine (bitter). The concentration of saccharin (0.03%) and quinine (30 μM) was used in the experiment and L-THP was given for 4 days while mice had access to saccharin or quinine. Consumption of saccharin or quinine was measured in the same way as describe above for ethanol.

2.4 Blood Ethanol Clearance (BEC) and Loss of Righting Reflex (LORR)

To examine the effect of L-THP on ethanol absorption, distribution or clearance that could contribute to altered drinking behavior, the effect of L-THP on blood ethanol clearance and ethanol-induced hypnosis were measured as previously described with minor modifications [11, 12]. Blood ethanol clearance was measured by injecting mice with 3.2 g/kg ethanol after pretreatment of three doses of L-THP (2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg). The blood was collected from each mouse 30 minutes, 1, 2, and 3 hours after the ethanol injection via tail bleeding. The plasma levels of ethanol were measured using Analox AM1 (Analox Instrument USA, Lunenburg, MA). The degree of hypnosis was measured as the duration of the loss of righting reflex to test the effect of L-THP on ethanol (3.2 g/kg)-induced hypnosis. Duration of the loss of righting reflex was determined when the mouse could position itself onto all 4 paws, 3 times in a 30-second time period.

2.5. Western Blot

Naïve mice were treated with acute L-THP (intraperitoneal) and Bromocriptine (intraperitoneal) according to our sequential treatment paradigm (the indicated times after drug administration). To investigate the effect of repeated L-THP injections (10 mg/kg injection/day for 4 days) on signaling molecules in mice exposed to ethanol, a separate group of mice was following a similar self-administration protocol as previously described above. In both cases, mice were anesthetized with carbon dioxide and rapidly decapitated. Brains were quickly removed and dissected to isolate the CPu and NAc in PBS on ice. Briefly, tissues were homogenized in a solution containing 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4), 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail type I and II (Sigma). Homogenates were centrifuged at 500 g at 4°C for 15 min and supernatants were collected. Proteins were analyzed using Bradford protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were separated by 4-12% NuPAGETM Bis Tris gels at 110 V for 2 h, transferred onto PVDF membranes at 30 V for 1 h (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and analyzed using antibodies against PKA (1:1000), pPKA (1:1000), ERK (1:1000), pERK (1:1000), AKT (1:1000), pSer473-AKT (1:1000) from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) and, GAPDH (1:1000, Millipore, Billerica, CA). Blots were developed using chemiluminescent detection reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Chemiluminescent bands were detected on a Kodak Image Station 4000R scanner (New Haven, CT) and quantified using NIH Image J software.

2.6. Assay for PKA Activity

PKA activity was measured using a solid phase enzyme-linked immuno-absorbent assay (ELISA) kit (ENZO Life Science, Plymouth Meeting, PA). The microplate wells, which were pre-coated with the substrate of PKA, were used according to the manufacture’s protocol. The kinase activity was initiated by 10 μl ATP addition, and was incubated for 90 minutes at 30 °C. Emptying contents of each well stopped the reaction. Phospho-specific substrate antibody was added to each well except the black, and incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes. The phospho-specific antibody was subsequently bound by a proxidase conjugated secondary antibody. The assay is developed with tetramethybenidine substrate and the color was proportional to PKA phosphotransferase activity. The absorbance in the reaction was measured at 450 nm in a microplate reader (Multiskan FC, Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). The absorbance was divided by the concentration of total protein (μg) in each sample and the data were represented as the relative activity of PKA.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) and were analyzed by unpaired two-tailed t-test (Western blot analysis) or two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc tests for individual comparisons (behavior experiments). Results of comparisons were considered significantly different if the P value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Systemic administration of L-THP decreases ethanol drinking

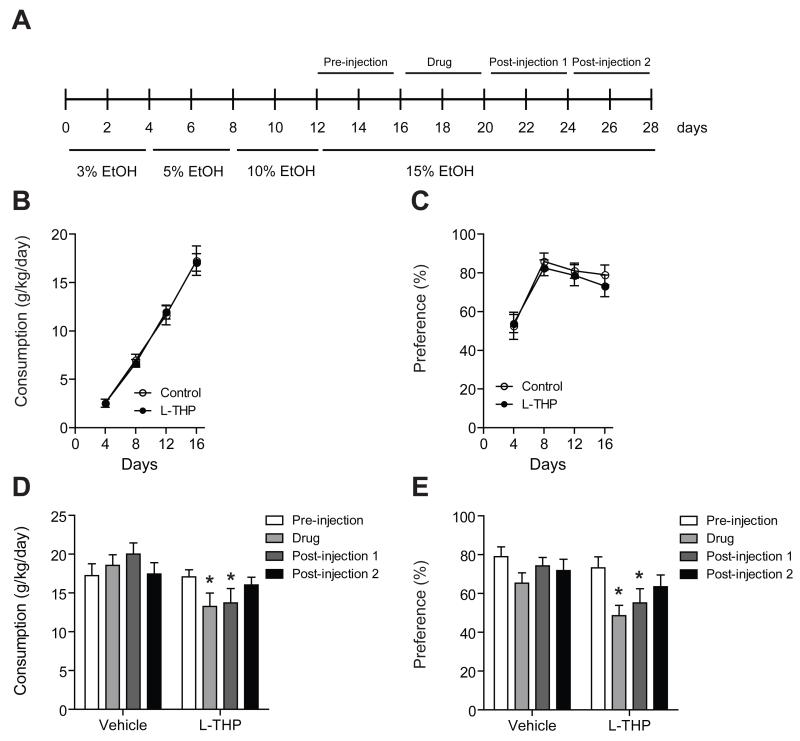

To determine whether treatment of L-THP can reduce alcohol drinking, we used a two-bottle choice drinking test (Fig. 1A). Over the course of the experiment, mice were provided water or increasing doses of ethanol (3%, 5%, 10%, and 15%). A behavioral profile of ethanol drinking across days 1-16 was monitored before mice were randomized to the L-THP treated group and the vehicle treated group. The preference of alcohol drinking was maintained after day 8 in our experiment and the profile of drinking was similar between the groups prior to the L-THP treatment (Fig. 1B and C). The administration of L-THP at a 10 mg/kg dose significantly reduced the consumption of alcohol drinking during the L-THP treatment period (injection period) compared to before L-THP injection (pre-injection period) during the 15 % ethanol session (Fig. 1D). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed effects of session (F6,153 = 65.8, P < 0.001) and the interaction between treatment and session (F6,153 = 5.41, P < 0.001), but did not show a significant effect of treatment (F1,153 = 3.47, P = 0.07). The Tukey post hoc test showed a significant difference in ethanol consumption between the before injection period and the L-THP injection period as well as between the before injection period and the first post-injection period.

Fig. 1.

Effect of L-THP on ethanol consumption and preference. (A) Timeline for two-bottle choice drinking. Behavioral profile of ethanol drinking across days 1-16 before mice were treated with L-THP or vehicle. Ethanol consumption (A) and preference (B) across days 1-16 (n = 12 for each treatment). Ethanol consumption (C) and preference (D) are significantly reduced during the L-THP-injection (10 mg/kg) period. All injection periods were performed while mice stably consumed 15% ethanol. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the pre- or post-injection period as indicated (Tukey test).

Moreover, the administration of L-THP at a 10 mg/kg dose significantly reduced the preference of alcohol drinking during the L-THP treatment period compared to before L-THP injection while mice steadily drank 15% ethanol (Fig. 1E). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed significant effects of session (F6,153 = 14.8, P < 0.001) and the interaction between treatment and session (F6,153 = 2.64, P = 0.02) but did not show a significant effect of treatment (F1,153 = 1.85, P = 0.18). The Tukey post hoc test showed a significant difference in ethanol preference between the before injection period and the L-THP injection period as well as between the before injection period and the first post-injection period.

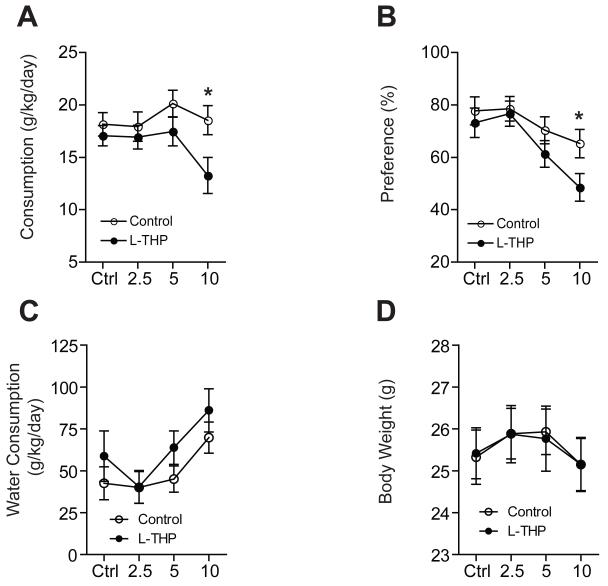

Then, we investigated the effect of different doses of L-THP (2.5, 5 and 10 mg/kg) on the consumption and preference of alcohol. We found that the treatment of L-THP significantly reduced the consumption of alcohol compared to the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 2A). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed significant effects of dose (F3,83 = 4.06, P = 0.01) and interaction between treatment and dose (F3,83 = 3.43, P = 0.02), but did not show a significant effect of treatment (F1,83 = 3.43, P = 0.13). The Tukey post hoc test showed a significant difference in ethanol consumption between the L-THP treatment group and the vehicle treatment group at an L-THP dose of 10 mg/kg. Also, the administration of L-THP significantly decreased preference for ethanol compared to the vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2B). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed significant effects of dose (F3,83 = 13.6, P < 0.001) and the interaction between treatment and dose (F3,83 = 3.17, P = 0.03), but did not show a significant effect of treatment (F1,83 = 2.16, P = 0.15). The Tukey post hoc test revealed a significant difference in ethanol preference between the two treatment groups at a 10 mg/kg L-THP dose. These results demonstrated that L-THP treatment (10 mg/kg) for 4 days, while mice steadily consumed 15% ethanol, reduced the consumption and preference of ethanol in mice. Importantly, this L-THP treatment did not alter water consumption or body weight when compared to vehicle treated mice (Fig. 2C and D). This indicates that the reduction of ethanol consumption and preference was not confounded by changes in body weight or water consumption.

Fig. 2.

Effect of different doses of L-THP on ethanol consumption and preference. Ethanol consumption (A) and preference (B) are significantly reduced by 10 mg/kg L-THP (n = 12 for each treatment). For water consumption (C) and body weight (D), there are no differences between the L-THP treatment group and mice treated with a vehicle (n = 12 for each treatment). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the pre- or post-injection period as indicated (Tukey test).

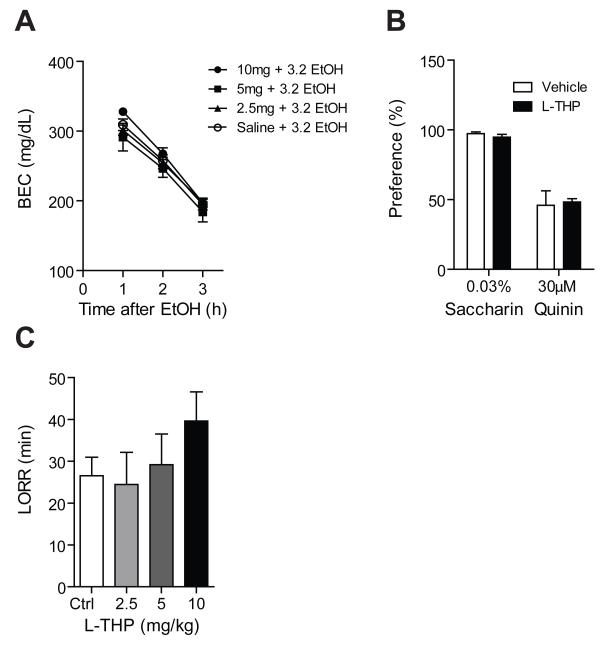

Since it is possible that mice may be drink less ethanol if L-THP alters ethanol metabolism, we tested blood ethanol clearance (BEC) in response to L-THP. Blood ethanol levels were similar in the four treatment groups [three different doses of L-THP (2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg) with ethanol (3.2 g/kg) and vehicle with ethanol as a control] at every hour after the administration of ethanol (P = 0.96) (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that the pharmacokinetics of ethanol metabolism were not changed by the treatment of L-THP. In addition, we examined whether L-THP treatment changes taste palatability. For testing the effect of L-THP on taste preference, we used saccharin for a sweet taste and quinine for a bitter taste in a modified two-bottle choice experiment. We found that administration of L-THP does not alter taste preference (P = 0.21) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of L-THP on blood ethanol clearance (BEC), taste preference, and loss of righting reflex (LORR). (A) No significant difference was observed in blood ethanol clearance between the L-THP treated and control mice (n = 10 for each treatment). (B) No differences by L-THP treatment in taste preference (saccharin for sweet and quinine for bitter taste) compared with mice treated by vehicle (n = 10 for each treatment). (C) No significant difference in the ethanol-induced hypnotic effect (LORR) was observed between the L-THP treated and control mice (n = 6 for each treatment). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Finally, to study the effect of L-THP on ethanol-induced hypnosis, we examined ethanol-induced loss of righting reflex (LORR) using a 3.2 g/kg ethanol dose. The group that received pretreatment with L-THP did not show a significantly different ethanol-induced LORR compared to the vehicle control group (Fig. 3C). Together, these data suggest that L-THP selectively reduces ethanol consumption as it does not reduce consumption of saccharine (sweet taste), quinine or water without altering the hypnotic properties or metabolism of ethanol.

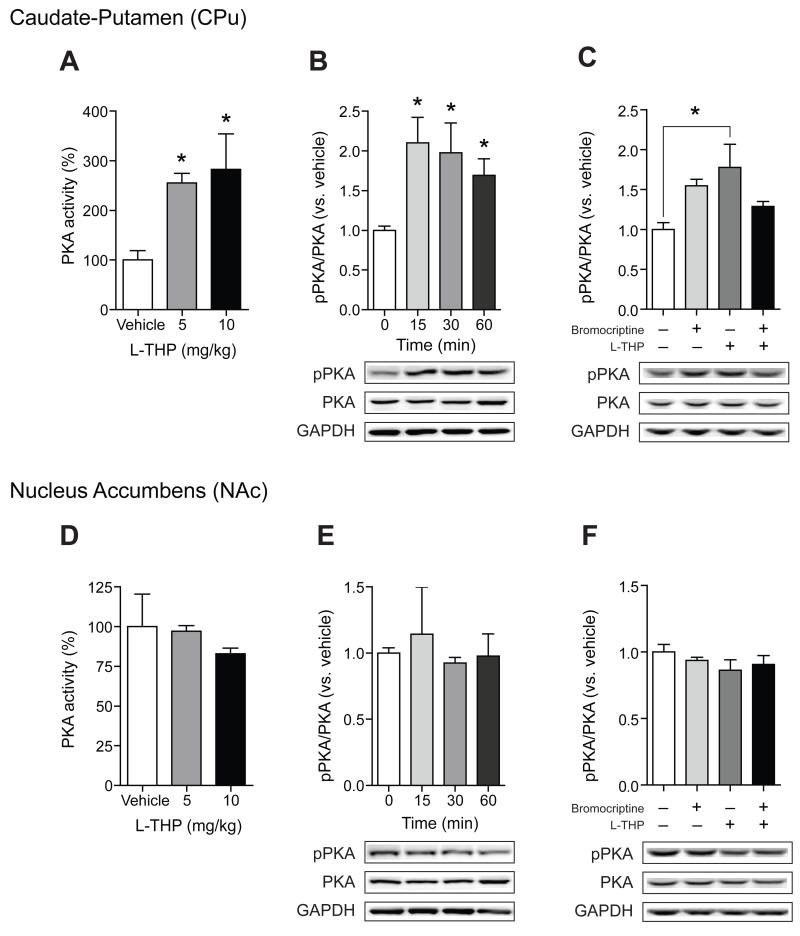

3.2. Systemic administration of acute L-THP phosphorylates and activates PKA via antagonizing D2R-mediated signaling in the caudate-putamen

Because L-THP is known to inhibit dopamine D2R, we examined whether L-THP regulates the activity of PKA in the striatum. C57BL/6J mice were systemically injected with two doses of acute L-THP (5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg) and the level of PKA activity via detecting PKA-specific substrates was measured 30 min after treatment. We found that acute exposure to L-THP significantly increased the activity of PKA in the CPu (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A) while PKA activity was not altered in the NAc (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that acute systemic injection of L-THP differentially triggers PKA activation in two striatal subregions. We further investigated whether levels of the active form of PKA (pPKA, Thr-198) in the CPu and NAc were altered in response to L-THP (10 mg/kg). Consistent with PKA activities (Fig. 4A), pPKA levels were increased in the CPu (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B) while no effect was observed in the NAc (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Effect of L-THP on PKA activity and the phosphrylation of PKA. PKA activity in CPu (A) and NAc (D) are measured as described in Methods. The activity of PKA in the CPu in the L-THP treatment group is increased in a dose-dependent manner (n = 4 mice for each treatment). However, PKA activity in the NAc in the L-THP treatment group is similar to that of the control group. Immunoblot of two different areas of the striatum and optical density quantification of PKA phosphorylation and PKA at various time points after L-THP treatment (10 mg/kg, ip, n = 4 mice per group). Administration of bromocriptine (10 mg/kg) 30 min before L-THP injection prevented the increase in the phosphorylation of PKA in the CPu (C) (n = 3 mice per group) while not effect was observed in the NAc (F). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Then, we examined whether increased pPKA levels were correlated with reduced D2R-mediated signaling. Thus, we tested if the pretreatment with a D2R agonist, bromocriptine, was able to normalize levels of pPKA. As we expected, pretreatment with bromocriptine decreased the L-THP-induced pPKA levels in the CPu (F3,8 = 4.39, P = 0.04) (Fig. 4C) while bromocriptine had no effect in the NAc (Fig. 4F). Together, these results support that the activation of PKA in the striatum by the treatment of L-THP is mainly mediated by D2Rs in the CPu.

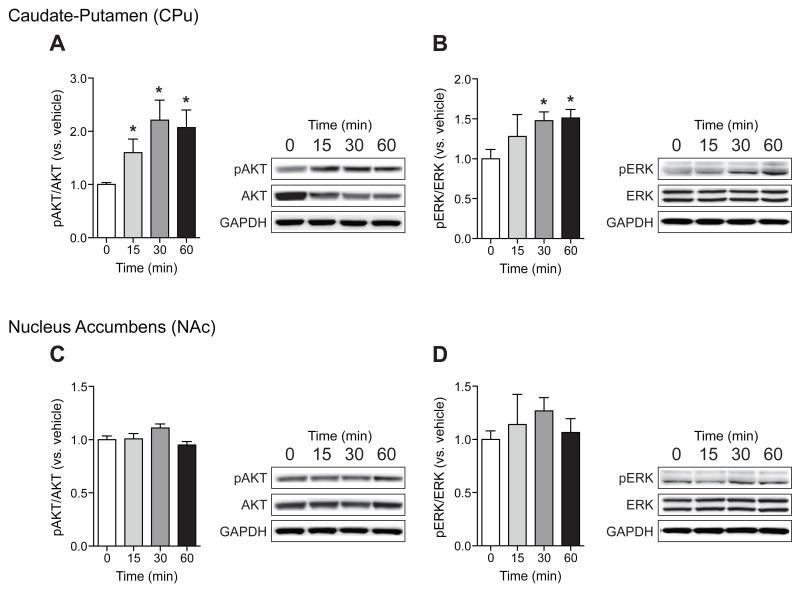

3.3. Acute L-THP phosphorylates and activates AKT and ERK in the caudate-putamen

Several lines of evidence suggest that blockade of dopamine signaling would modulate AKT activity [13]. In addition, it has already been shown that tetrahydroberberine (D1/D2R antagonist) increases the expression of pAKT against H2O2 [14]. Thus, we measured pAKT (Ser-473) levels in response to L-THP (10 mg/kg). As expected, we found increased pAKT levels in the CPu (Fig. 5A) while no significant changes were observed in the NAc (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, because treatment of D2R antagonists has also been shown to activate ERK in the striatum, we further investigated whether ERK signaling might be involved in the pharmacological action of L-THP (Fig. 5B and D). Systemic injection of acute L-THP (10 mg/kg) increased levels of the activated from of ERK, pERK (Thr202/Tyr204), in the CPu (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B), but not in the NAc (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Effect of L-THP on the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK. Immunoblot and optical density quantification of pAKT, AKT, and GAPDH as a control (A) (n = 6 mice for each treatment) as well as pERK, ERK, and GAPDH as a control (B) in CPu at various time points after L-THP treatment (n = 4 mice for each treatment). Immunoblot and optical density quantification of pAKT, AKT, and GAPDH as a control (C) (n = 6 mice for each treatment) as well as pERK, ERK, and GAPDH as a control (D) in the NAc at different time points after L-THP treatment (n = 4 mice for each treatment). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

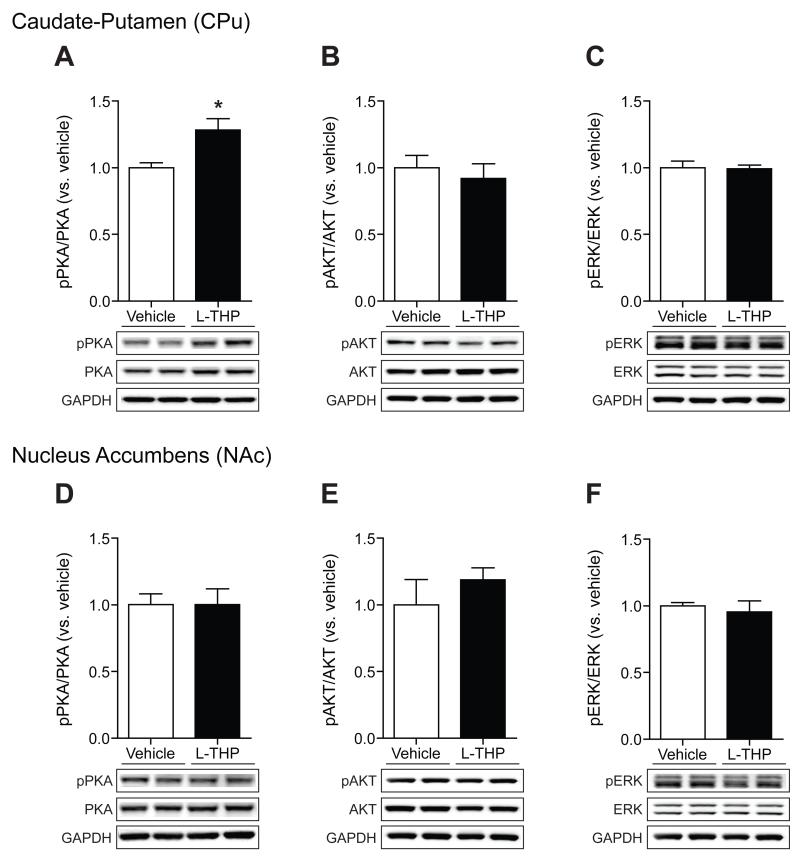

3.4. Increased pPKA in the caudate-putamen in response to repeated L-THP treatment in mice self-administering ethanol

Next, we asked whether repeated L-THP administration altered kinase activity in mice in consistent ethanol drinking. Thus, we examined the effect of L-THP on the active form of three kinases, pPKA, pAKT, and pERK using mice that were drinking 15% ethanol. L-THP was administered for 4 days as shown in the drinking scheme in Figure 1A. Mice were given L-THP (10 mg/kg, daily) for 4 consecutive days and the CPu and the NAc were isolated 30 min after the last L-THP treatment. We found that L-THP treatment increases pPKA levels significantly in the CPu (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A), but not in the NAc (Fig. 6D). In contrast to the effect of acute L-THP, no differences were detected for pAKT (Fig. 6B and E), or pERK (Fig. 6C and F) in either striatal region. These results suggest that elevated PKA activity by L-THP contributes to reduce ethanol drinking in mice.

Fig. 6.

Effect of repeated L-THP treatment on the phosphorylation of PKA, AKT and ERK in ethanol exposed mice. Immunoblot and optical density quantification of pPKA, PKA, and GAPDH as a control (A), pAKT, AKT, and GAPDH as a control (B), and pERK, ERK, and GAPDH as a control (C) in CPu 30 min after the last L-THP treatment (n = 4 mice for each treatment). Immunoblot and optical density quantification of pPKA, PKA, and GAPDH as a control (D), pAKT, AKT, and GAPDH as a control (E), and pERK, ERK, and GAPDH as a control (F) in the NAc at 30 min after last L-THP treatment (n = 4 mice for each treatment). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we present the pharmacological effect of L-THP on ethanol drinking as well as on key signaling molecules that have previously been shown to regulate ethanol drinking in two striatal regions, the CPu and NAc. For the first time, we demonstrated that L-THP reduces ethanol self-administration in a two-bottle choice drinking experiment. Since L-THP increases the active form of PKA in the CPu, but not in the NAc, which could be reversed by a dopamine D2R agonist, our results indicate that L-THP mainly inhibits D2R in the CPu, which mainly receives dopamineric input from the SNr. Because L-THP has also been shown to regulate other receptors or channels [6], we do not rule out other receptor- or channel-mediated signaling contributes to the pharmacological effect of L-THP on striatal D2R. A recent study suggested that L-THP antagonizes alpha-1 adrenergic receptors [15]. Interestingly, the blockade of alpha-1 adrenergic receptors has been reported to suppress excessive ethanol consumption in ethanol-dependent rats [16], suggesting that inhibiting alpha-1 adrenergic receptors by L-THP could also contribute to reducing ethanol drinking in mice.

Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of PKA activity has been shown to decrease sensitivity to the ataxic and hypnotic effects of ethanol [17, 18]. Furthermore, inhibition of PKA signaling, especially in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and the NAc, resulted in increased ethanol consumption via a CREB-dependent mechanism [19, 20]. Therefore, the pharmacological action of L-THP in the CPu, which resulted in increased PKA activity, could contribute to the suppression of ethanol intake observed in our study.

Our results revealed differential effects of L-THP on the activation of PKA in two different sub-regions of the striatum. In general, stimulation of D2Rs leads to decreased adenyl cyclase activity via an inhibitory G protein (Gi), reducing PKA activation [21]. On the other hand, antagonizing D2R presumably relieves this inhibition, leading to the activation of PKA. D2R antagonist, eticlopride, failed to induce PKA-mediated gene expression, which was in contrast to previous results that the involvement of PKA is necessary for haloperidol-induced gene expression [22]. The discrepancy may be due to the fact that eticlopride is more selective for D2Rs than is haloperidol [23]. In addition, haloperidol, like L-THP, has affinity for other types of receptors including histamine H1 receptors and muscarinic M1 acetylcholine receptors [24]. Another possible explanation for our results may be that other signaling pathways such as PKC, DAG and IP3 may be responsible for mediating L-THP-induced gene expression. The formation of DAG and IP3 has been shown to be inhibited by the stimulation of D2Rs [25]. The inhibition of D2Rs may lead to an enhanced activation of PKC and the release of calcium from intracellular stores by DAG and IP3, which may play a role in L-THP-mediated gene expression. Further experiments are warranted to determine which combinations of kinase pathways regulates ethanol drinking in mice in response to L-THP.

Recent studies describe that both AKT and ERK signaling are implicated in ethanol sensitivity; the activation of AKT signaling enhanced ethanol sensitivity while the stimulation of ERK reduced ethanol sensitivity [26]. However, inhibition of AKT signaling in the NAc reduced excessive voluntary ethanol consumption and self-administration in rats [27]. Furthermore, systemic administration of the MEK inhibitor SL327 increases operant self-administration of ethanol in mice [28]. Consistently, our study suggests that L-THP-activated AKT and ERK signaling in the CPu, which contributes to the reduction in ethanol drinking.

Considering the importance of D2R in reward-related behaviors, moderately potent antagonist with a longer-half life such as L-THP, may be capable of blocking D2R in the brain without altering normal reward behaviors. This appears to be the case in our study as L-THP did not alter consumption of saccharine. In addition, treatment of L-THP at an effective dose can reduce alcohol drinking without inducing a sedative effect. This is also evident by the fact that mice did not reduce water consumption while treated with L-THP. Furthermore, L-THP does not cause any major side effects, based on results from its use as a traditional medication for opiate addiction [29]. Also, L-THP has no effect on opioid receptors and its analgesic effect cannot be antagonized by naloxone [6]. These studies suggest that L-THP could be a novel therapeutic compound for the treatment of AUD.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the treatment of L-THP reduced ethanol intake and preference without altering water or saccharine intake. Our data suggest that both acute and repeated admiration of L-THP increases PKA-mediated signaling in the CPu, which may be causally related to reduced alcohol drinking.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sun Choi and Denise Walker for expert technical assistance, Christina Ruby for advice for behavioral experiments, as well as Hyung Nam and Steve Brimijoin for helpful discussion. This project was funded by the Samuel Johnson Foundation for Genomics of Addiction Program at Mayo Clinic and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to D. -S. C. (P20 AA017830-Project 1).

Abbreviations

- L-THP

levo-tetrahydropalmatine

- PKA

protein kinase A

- AKT

AKT8 virus oncogene cellular homolog

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- CPu

caudate putamen

- CeA

central amygdala

- MEK

MAPK/Erk kinase

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- CREB

cAMP responsive element binding protein.

5 References

- [1].Spanagel R. Alcoholism: a systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:649–705. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haney M, Spealman R. Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:403–19. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1079-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jin GZ, Wang XL, Shi WX. Tetrahydroprotoberberine--a new chemical type of antagonist of dopamine receptors. Sci Sin B. 1986;29:527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mantsch JR, Wisniewski S, Vranjkovic O, Peters C, Becker A, Valentine A, et al. Levo-tetrahydropalmatine attenuates cocaine self-administration under a progressive-ratio schedule and cocaine discrimination in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97:310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu YL, Yan LD, Zhou PL, Wu CF, Gong ZH. Levo-tetrahydropalmatine attenuates oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hu JY, Jin GZ. Supraspinal D2 receptor involved in antinociception induced by l-tetrahydropalmatine. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1999;20:715–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chu H, Jin G, Friedman E, Zhen X. Recent development in studies of tetrahydroprotoberberines: mechanism in antinociception and drug addiction. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:491–9. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9179-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Joel D, Weiner I. The connections of the dopaminergic system with the striatum in rats and primates: an analysis with respect to the functional and compartmental organization of the striatum. Neuroscience. 2000;96:451–74. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yin HH, Ostlund SB, Balleine BW. Reward-guided learning beyond dopamine in the nucleus accumbens: the integrative functions of cortico-basal ganglia networks. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1437–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Figueroa-Guzman Y, Mueller C, Vranjkovic O, Wisniewski S, Yang Z, Li SJ, et al. Oral administration of levo-tetrahydropalmatine attenuates reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking by cocaine, stress or drug-associated cues in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee MR, Hinton DJ, Unal SS, Richelson E, Choi DS. Increased ethanol consumption and preference in mice lacking neurotensin receptor type 2. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nam HW, Lee MR, Zhu Y, Wu J, Hinton DJ, Choi S, et al. Type 1 equilibrative nucleoside transporter regulates ethanoldrinking through accumbal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor signaling. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:1043–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Beaulieu JM, Del’guidice T, Sotnikova TD, Lemasson M, Gainetdinov RR. Beyond cAMP: The Regulation of Akt and GSK3 by Dopamine Receptors. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:38. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang L, Zhou R, Xiang G. Stepholidine protects against H2O2 neurotoxicity in rat cortical neurons by activation of Akt. Neurosci Lett. 2005;383:328–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lu ZZ, Wei X, Jin GZ, Han QD. [Antagonistic effect of tetrahydroproberberine homologues on alpha 1-adrenoceptor] Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1996;31:652–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Walker BM, Rasmussen DD, Raskind MA, Koob GF. alpha1-noradrenergic receptor antagonism blocks dependence-induced increases in responding for ethanol. Alcohol. 2008;42:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lai CC, Kuo TI, Lin HH. The role of protein kinase A in acute ethanol-induced neurobehavioral actions in rats. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:89–96. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000263030.13249.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thiele TE, Willis B, Stadler J, Reynolds JG, Bernstein IL, McKnight GS. High ethanol consupmtion and low sensitivity to ethanol-induced sedation in protein kinase A-mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pandey SC, Roy A, Zhang H. The decreased phosphorylation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding (CREB) protein in the central amygdala acts as a molecular substrate for anxiety related to ethanol withdrawal in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:396–409. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000056616.81971.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pandey SC, Zhang H, Roy A, Misra K. Central and medial amygdaloid brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling plays a critical role in alcohol-drinking and anxiety-like behaviors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8320–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stoof JC, Kebabian JW. Two dopamine receptors: biochemistry, physiology and pharmacology. Life Sci. 1984;35:2281–96. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Adams AC, Keefe KA. Examination of the involvement of protein kinase A in D2 dopamine receptor antagonist-induced immediate early gene expression. J Neurochem. 2001;77:326–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kohler C, Hall H, Gawell L. Regional in vivo binding of the substituted benzamide [3H]eticlopride in the rat brain: evidence for selective labelling of dopamine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;120:217–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90543-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Arnt J, Skarsfeldt T. Do novel antipsychotics have similar pharmacological characteristics? A review of the evidence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:63–101. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pizzi M, D’Agostini F, Da Prada M, Spano PF, Haefely WE. Dopamine D2 receptor stimulation decreases the inositol trisphosphate level of rat striatal slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;136:263–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90724-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Eddison M, Guarnieri DJ, Cheng L, Liu CH, Moffat KG, Davis G, et al. arouser reveals a role for synapse number in the regulation of ethanol sensitivity. Neuron. 2011;70:979–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Neasta J, Ben Hamida S, Yowell QV, Carnicella S, Ron D. AKT signaling pathway in the nucleus accumbens mediates excessive alcohol drinking behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:575–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Faccidomo S, Besheer J, Stanford PC, Hodge CW. Increased operant responding for ethanol in male C57BL/6J mice: specific regulation by the ERK1/2, but not JNK, MAP kinase pathway. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;204:135–47. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1444-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yang Z, Shao YC, Li SJ, Qi JL, Zhang MJ, Hao W, et al. Medication of l-tetrahydropalmatine significantly ameliorates opiate craving and increases the abstinence rate in heroin users: a pilot study. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:781–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]