Abstract

During early wound healing (WH) events Connexin 43 (Cx43) is down-regulated at wound margins. In chronic wound margins, including diabetic wounds, Cx43 expression is enhanced suggesting that down-regulation is important for WH. We previously reported that the Cx43 mimetic peptide Gap27 blocks Cx43 mediated intercellular communication and promotes skin cell migration of infant cells in vitro. In the present work we further investigated the molecular mechanism of Gap27 action and its therapeutic potential to improve WH in skin tissue and diabetic and non-diabetic cells. Ex vivo skin, organotypic models and human keratinocytes/fibroblasts of young and old donors and of diabetic and non-diabetic origin were used to assess the impact of Gap27 on cell migration, proliferation, Cx43 expression, localization, phosphorylation and hemichannel function. Exposure of ex vivo WH models to Gap27 decreased dye spread, accelerated WH and elevated cell proliferation. In non-diabetic cell cultures Gap27 decreased dye uptake through Cx hemichannels and after scratch wounding cells showed enhanced migration and proliferation. Cells of diabetic origin were less susceptible to Gap27 during early passages. In late passages these cells showed responses comparable to non-diabetic cells. The cause of the discrepancy between diabetic and non-diabetic cells correlated with decreased Cx hemichannel activity in diabetic cells but excluded differences in Cx43 expression, localization and Ser368-phosphorylation. These data emphasize the importance of Cx43 in WH and support the concept that Gap27 could be a beneficial therapeutic to accelerate normal WH. However, its use in diabetic WH may be restricted and our results highlight differences in the role of Cx43 in skin cells of different origin.

Keywords: wound healing, gap junctions, hemichannels, migration, proliferation, skin

Introduction

Connexins are single protein subunits of gap junctions (GJs), cell–cell junctions important for direct cell–cell communication. Six connexins oligomerize to form a connexon (connexin hemichannel [CxHc]), two CxHcs from neighbouring cells dock to form functional GJ channels permitting direct exchange of small molecules (<1.8 kD) between adjacent cells [1]. Prior to forming GJ channels, CxHcs can, under specific physiological conditions, be induced to open providing a pathway for the cell to release paracrine messengers into the extracellular space [2]. Cxs play important roles in proliferation, migration and differentiation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts and are involved in wound healing (WH) [3]. Connexin 43 (Cx43), the most prominent Cx in the epidermis, is down-regulated at the wound margins during early WH [4–6] and is abnormally expressed at wound margins of chronic ulcers. Hence targeting of Cx43 in chronic wounds has recently attracted interest [6–8].

The positive effect of Cx43 down-regulation on normal WH has been shown using antisense DNA and gene knock-out studies in a number of mouse models [5, 8–11]. Recently, we described a beneficial effect of Gap27 on scratch wound closure rates that correlated with decreased gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) in cultured human keratinocytes and fibroblasts from young healthy donors [12]. Gap27 is a small synthetic connexin mimetic peptide with a sequence homology to the second extracellular loop of Cx43 [13, 14] and is a benign, specific and reversible inhibitor of Cx43 mediated direct cell–cell communication [13], which does not influence Cx43 expression levels [15].

However, an effect of such Cx43-targeting mimetic peptides in whole tissue and in adult human skin cells – which will be the main targets in wound therapy – has yet to be determined. Furthermore, the molecular mechanisms of Gap27 action in skin cells have to be further elucidated.

We have previously shown that Cx43 down-regulation is also impaired at the wound margins of diabetic wounds and Mori and colleagues found positive effects of a Cx43 antisense gel on WH in rats with streptotocin induced diabetes [6, 10]. As diabetic foot syndrome is a major complication in diabetes and causes substantial lower-limb amputation rates [16] new therapies are imperatively needed in this field. Cx43-mimetic peptides might, along with Cx43 antisense gels, be promising therapeutic options for this disease. To verify this hypothesis we investigated the influence of Gap27 on diabetic compared to non-diabetic cells.

We show for the first time that Gap27 is effective in enhancing wound closure in porcine and human ex vivo skin and organotypic models and also demonstrate its influence on migration and proliferation in human skin cells from adult donors. Functional studies reveal that Gap27 influences hemichannel gating and GJIC-related phosphorylation while Cx43 protein levels and localization were not changed. Surprisingly, diabetic cells were less susceptible to Gap27 treatment in the first passages concerning cell proliferation, migration and hemichannel gating. Interestingly, in late passages diabetic cells showed behaviour comparable to non-diabetic cells, suggesting diabetic cells exhibit a memory of their origin but loose this diabetic phenotype over time in culture.

Materials and methods

Cell sources

This study was approved by the Ethics committee of the University of Magdeburg, Germany. Informed consent was obtained from 10 diabetic patients [two women and eight men aged 66 ± 9 years, diabetes (type 2) duration 11 ± 5 years, A1C 7.23 ± 1.2 (amount of glucosylated haemoglobin)] and 11 non-diabetic healthy volunteers (four women and seven men aged 52 ± 10 years, A1C 6.61 ± 0.3). Human skin tissue for WHM was obtained from three donors (women, aged 39 ± 2 years) after plastic surgery, skin samples from infant donors (<5 years) used for cell culture was obtained following medical circumcisions. Their use was approved by the ethics committee of the Aerztekammer Hamburg (060900). For 3D organotypic cultures cells were derived from paediatric foreskins discarded at surgery following informed consent with ethical approval by Yorkhill Hospital Trust Research Ethics Committee, Glasgow, UK [12].

Connexin mimetic peptides

Lyophilized connexin-mimetic peptide Gap27 directed to the second extracellular loop of Cx43 (SRPTEKTIFII) and control peptide Gap 18 directed to cytoplasmic regions of Cx43 (MGDWSALGKLLDKVQAC) (Peptide Specialty GmbH, Heidelberg/Germany, or Zealand Pharma, Glostrup, Denmark) were reconstituted as recently described [12]. Gap 18 was previously shown to be a valuable control for Gap27 [17].

Cell culture

Human fibroblasts and keratinocytes were isolated from foreskin and skin biopsies and cultured according to a method modified from Rheinwald and Green [18]. Keratinocytes were maintained in serum-free KGM-2 (Promocell, Heidelberg/Germany) with defined growth supplement and 100 μg/ml P/S. Fibroblasts were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) containing 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 100 μg/ml P/S. Experiments were carried out in passages 2 to 5 (early passages) and 12 to 15 (late passages). Peptides were added to serum-free medium to final concentrations of 0.6, 0.1, 0.06 or 0.006 mM as required. Comparison of the influence of Gap18 and PBS did not show any differences. Therefore some experiments were performed only with PBS control due to limitations of the amount of cells and peptide.

For organotypic cultures keratinocytes and fibroblasts were prepared and maintained as previously described [12]. Three-dimensional human organotypic cultures were derived from the method successfully developed for mouse models in our laboratory [15] and cultured in Epilife®. Once stratification was complete (up to 2 weeks culture) a scratch wound was introduced through the stratified keratinocytes using a sterile tip. Following wounding Gap27 (0.1 mM) was added to the lower chamber of the transwell and replaced at 18 hr intervals as previously described [15]. Wound widths in control- and peptide-treated cultures were subsequently measured at regular intervals as previously described [12].

Porcine and human ex vivo WHM (granted patent DE 10317400) and evaluation of reepithelization

To investigate the effect of Gap27 on reepithelization and dye spread, porcine or human WH models were used as described previously [6]. Porcine skin was obtained from a local slaughter house. After washing and disinfecting the pig’s ears, punch biopsies with a diameter of 6 mm were taken from the plicae of the ears. Fat, subcutis and parts of the dermis were removed. Subsequently, wounds were generated by removing the epidermis and the upper dermis from the centre of the biopsies with a 3 mm biopsy device. These ex vivo WHM were placed dermis side down on gauze into culture dishes filled with DMEM supplemented with hydrocortisone, foetal calf serum, penicillin/streptomycin and cultured on ‘air-liquid interface’ for up to 48 hrs (10% CO2, 37°C). This time period was evaluated in previous experiments to show most pronounced effects. Five microlitres of peptide (0.6 mM) or PBS, respectively, were applied into each WHM directly after wounding and treatment was repeated after 24 hrs. The samples were then snap-frozen in isopentane pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C. Cryostat sections (6 μm) of the middle of each WHM were HE-stained for evaluation. Reepithelization at both wound margins from two different sections was appraised using a DMLS light microscope (Leica GmbH, Wetzlar/ Germany) and evaluation performed as previously described [19].

Cell migration assays

Cells were seeded at 1 × 106 (keratinocytes) or 0.8 × 106 (fibroblasts) cells in 12-well plates and grown to confluency. Cell proliferation was inhibited by x-ray radiation (30 Gray). Peptide treatment was performed for 1.5 hrs in serum-free medium, followed by introduction of a scrape wound of around 500 μm using a 100 μl pipette tip. Migration was monitored over the following 48 hrs and the cell scratch width was measured using ImageJ software (NIH). Peptide treatment (0.06 mM for non-diabetic cells, 0.6, 0.06 and 0.006 mM for diabetic cells) was repeated every 24 hrs to maintain peptide efficacy as we have previously shown that Gap27 loses its GJ inhibitory capacity after 12 hrs in culture [12]. Three-dimensional cultures were similarly treated and analysed as previously described [12].

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were grown on cover slips to confluent monolayers, scratched and treated with Gap27 (0.06 mM for non-diabetic cells, 0.6, 0.06 and 0.006 mM for diabetic cells) or PBS every 24 hrs. Cells were fixed at 24, 48 hrs and 72 hrs after wounding and immunostained for Ki67. Proliferation was determined by counting Ki67+ cells at the scratch margins in comparison to total cell number. Three visual fields per sample were counted for evaluation. In WHM, the proportion of Ki67+ cells compared to the total number of cells was determined at wound margins, in the regenerating epidermis and in unaffected epidermis.

Propidium iodide uptake assays

Dye uptake assays were performed by a method modified by those reported by Contreras et al., Braet et al. and Schalper et al.[20–22]. Cells were seeded on cover slips placed in 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells (keratinocytes) or 2.5 × 104 cells (fibroblasts) per well and grown overnight. These low cell numbers resulted in scattered localization of the cells and widely prevented formation of cell–cell contacts. Prior to dye uptake experiment cells were treated with Gap27 or Gap18, respectively (0.06 mM), for 1 hr in low Ca2+-medium. Stock solutions of dyes were prepared in Ca2+/Mg2+-free PBS, diluted in keratinocyte basal medium (KGM-2 without supplements) or serum-free RPMI to their final concentration (2.5 mM propidium iodide, 0.1 μM calcein-AM (Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe/ Germany), 25 mM TRITC dextran (4 kD [Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim/ Germany]) and added to the cells for 5 min. at room temperature. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS containing Ca2+/Mg2+ to shut the hemichanels and evaluated immediately; the number of labelled cells was determined. Experiments were repeated in triplicate per setting and on three separate occasions.

Ex vivo dye transfer experiments and image analysis

Directly after wounding, WHM were treated with PBS or 0.6 mM Gap27 or Gap18, respectively, and incubated for 1 hr. Afterwards, substances were removed from the wounds via pipette and Lucifer Yellow (Sigma-Aldrich, 4%w/v in PBS) and TRITC dextran (Sigma-Aldrich, 25 mg/ml) applied to the wounds followed by 5 min. of incubation. Dye spread was examined by using Axiophot II fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss, Göttingen/Germany). Gain and exposure time were kept constant during image acquisition. Digital RGB images were analysed using ImageJ software (NIH). By applying the ‘segmented lines’ tool the extent of dye transfer or ‘travelling distance’ was aligned individually for each image and an intensity graph across that range was generated. A grey level intensity below 50% of the highest intensity (wound margin) was arbitrarily taken as the limit to which Lucifer Yellow had spread. Four sections were analysed from each WHM.

Immunofluorescence

Immunostaining was performed as previously described (for tissues and cultured cells see [6], for organotypic models see [15]). Antibodies were used as follows: Anti-Cx43 (clone C13720, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, USA; 1:50 (cells and tissue), polyclonal Cx43 antibody, kindly provided by Dr. E Rivedal [12] 1:500 (3D organotypic)), anti-Ki-67 (clone M7240, DAKO, Glostrup/Denmark) 1:50 (tissues), 1:20 (cells). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (1:1500 in PBS).

Western blot analysis

Cultured cells were washed with PBS and subsequently lysed in buffer containing 1% v/v NP-40, 0.5% v/v deoxycholate, 0.1% w/v SDS, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 140 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0 and a cocktail of protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of total protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. After blocking for 1 hr with 5% w/v dry milk powder in tris-buffered saline + tween 20 (TBST) buffer, membranes were probed with the antibodies as follows: Anti-α tubulin (clone CP06, Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NY, USA) 1:300, anti-Cx43 (clone C13720) 1:250, anti-Phospho-Cx43 (#3511, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) 1:100. For detection, horseradish peroxidase coupled secondary antibodies directed against mouse or rabbit, respectively, were used (1:5000, Dianova, Hamburg, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed on data using one-way analysis of variance with Student’s t-test (paired and unpaired) and Dunnett’s post-test as appropriate. Statistical significance was inferred at P < 0.05.

Results

Beneficial effect of Gap27 on reepithelization in 3D skin models

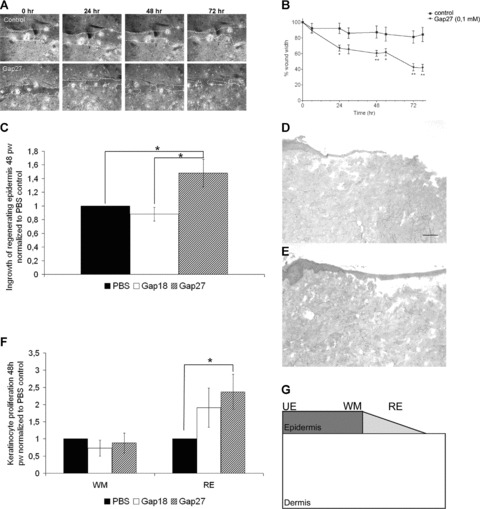

To date beneficial effects of Gap27 on WH were only demonstrated in 2D monocultures and in a mouse 3D organotypic model [15]. To further investigate the influence of Gap27 in 3D systems of higher mammals, wound closure of in vitro human organotypic models and ex vivo total skin wound healing models (WHM) was monitored after treatment with Gap27 or a control peptide. Gap27 significantly accelerated wound closure in human organotypic models at 24, 48 and 72 hrs (Fig. 1A, B) as well as in porcine WHM at 48 hrs (Fig. 1C–E). The doses used (0.1 mM for organotypic models, 0.6 mM for ex vivo models) have been defined before to be most effective ([12], [15]; unpublished data Hamburg). Similar results were also found in human WHM but due to the low sample number without statistical significance (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Effect of Gap27 on wound closure in human in vitro organotypic models and porcine ex vivo WHM. (A), (B) Following scratching of the epidermal layer, migration rates of cells closing the in vitro wound in human organotypic models were significantly increased over 3 days by 0.1 mM Gap27. (C) Comparison of reepithelization in porcine WHM treated with 0.6 mM Gap27 or Gap18, respectively, normalized to PBS-treated control models 48 hrs after wounding (pw). (D), (E) Haematoxylin and eosin staining of frozen sections of WHM treated with PBS (D) and 0.6 mM Gap27 (E) 48 hrs after wounding. Note the clearly extended regenerating epidermis in the Gap27-treated model. (F) Comparison of the proportions of proliferating cells at the wound margins and in the regenerating epidermis of WHM treated with 0.6 mM Gap27 or Gap18, respectively, normalized to PBS-treated control models. (G) Areas in which keratinocyte proliferation was quantified by counting Ki67+ cells: unaffected epidermis, wound margin, regenerating epidermis (n= 9; *P < 0.05, values represent mean ± S.E.M. Scale bar = 50 μm.).

Investigation of Ki67+ cells in porcine WHM revealed a significantly higher rate of proliferating cells in the regenerating epidermis after treatment with 0.6 mM Gap27 compared to control models (Fig. 1F). It had no significant effect on keratinocyte proliferation at wound margins (Fig. 1F) and in areas of the epidermis distant from the wound (‘unaffected epidermis’; data not shown).

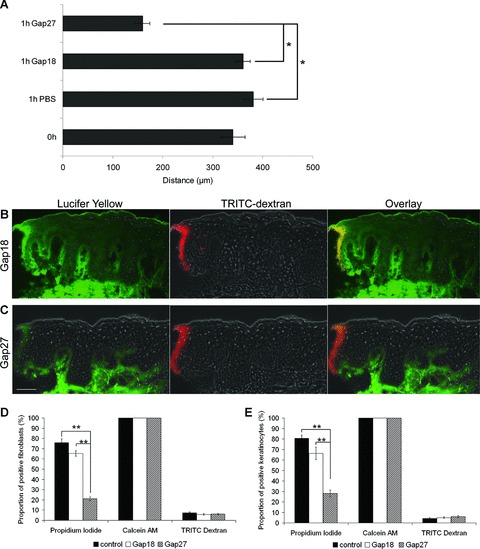

Gap27 decreases connexin mediated signalling events in WHM

In order to investigate the effect of Gap27 on spread of a fluorescent dye which is able to pass through GJ channels as well as hemichannels (CxHcs) [4, 20], the extent of Lucifer Yellow (LY) spread into the porcine WHM epidermis was examined following exposure to Gap27, the control peptide Gap18 or PBS for 1 hr. This revealed a significantly reduced spread of LY into the epidermis of WHM treated with Gap27 compared to control (Fig. 2A–C). To check whether the first cells at the wound margins were damaged and were therefore able to take up LY and pass it to other epidermal cells via GJ channels, TRITC dextran was additionally applied to the wounds. TRITC dextran entered (damaged) cells at the wound margins but due to its molecular mass (4 kD) had restricted permeability and was unable to diffuse into other cells via GJs and was therefore only detectable in cells at the wound margins (Fig. 2B, C). Therefore, the LY dye spread can be mediated by GJ channels. However, as LY can pass through CxHcs the dye spread can also reflect the uptake of LY via hemichannels.

Fig 2.

Effect of Gap27 on dye transfer and dye uptake. (A) Statistical evaluation of Lucifer yellow dye spread into the epidermis of ex vivo WHM directly after wounding (0 hr) and after 1 hr of incubation with PBS, 0.06 mM Gap18 or 0.06 mM Gap27, respectively (n= 6; *P < 0.05, values represent mean ± S.E.M.). (B, C) Fluorescence microscopy of the dye spread of Lucifer Yellow (green) and TRITC dextran (red) into wound edges of WHM after 1 hr of incubation with Gap18 (B) or Gap27 (C) (Scale bar = 50 μm). (D, E) Investigation of Cx-hemichannel permeability: Proportion of tracer positive cells (left: propidium iodide, middle: Calcein AM, right TRITC Dextran; (D) fibroblasts (E) keratinocytes) normalized to the total amount of cells in 0.06 mM Gap18 or 0.06 mM Gap27 treated and control cells (n= 9, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, values represent mean ± S.E.M.).

Gap27 influences hemichannel function in cultured keratinocytes and fibroblasts

The dye spread experiment described above in WHM cannot distinguish between GJIC from cell to cell and the release and uptake of dyes to and from the extracellular space reflecting communication via CxHcs. We have recently determined that Gap27 is able to attenuate GJIC in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts [12]. In addition, it is an effective inhibitor of CxHxs in endothelial and airway cells [2]. In order to analyse whether Gap27 also affects Cx43 hemichannels in skin cells we investigated dye uptake of the cationic probe propidium iodide. Significantly less propidium iodide positive cells were found in Gap27-treated fibroblast and keratinocyte cultures compared to Gap18 treated or untreated cells, strongly suggesting that Gap27 affects Cx43 hemichannels in skin cells (Fig. 2D, E). To control for cell viability which might influence the uptake of dye tracers the 4 kD TRITC dextran which cannot pass through intact plasma membranes and is therefore only found in damaged cells was used. In addition, we used the membrane-permeant dye calcein AM which can enter cells through the plasma membrane. The absence or presence of both dye tracers was similar in all cell cultures indicating the specific influence of Gap27 on CxHcs (Fig. 2D, E).

Gap27 accelerates migration and proliferation in infant and adult human skin cells

Formation of granulation tissue followed by reepithelization is important for effective wound closure. Accordingly, migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes is crucial in the WH process.

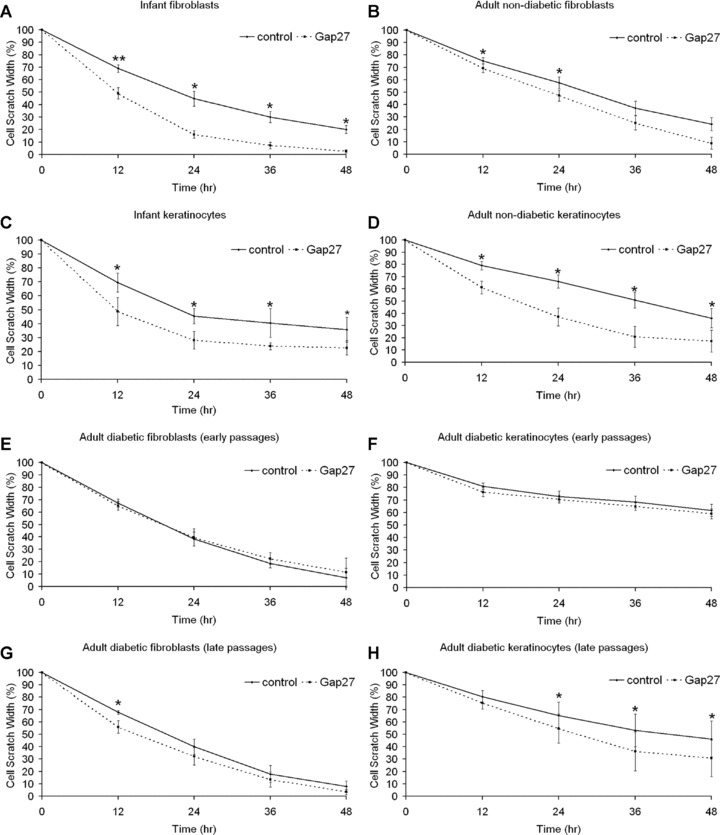

Cell cycle arrested fibroblasts and keratinocytes of different donor age were treated with PBS or Gap27 (0.06 mM) shortly before the introduction of a scratch wound. Enhanced cell migration occurred in infant fibroblast cultures and in adult fibroblasts, although this was less pronounced (Fig. 3A, B). Infant and adult keratinocytes also showed significantly accelerated migration (Fig. 3C, D).

Fig 3.

Effect of 0.06 mM Gap27 on fibroblast and keratinocyte migration. Cell cycle arrested human primary infant, adult non-diabetic and adult diabetic fibroblast and keratinocyte cultures were scratch wounded and treated with Gap27 or PBS, respectively. Effect of Gap27 on migration of (A, C) infant, (B, D) adult non-diabetic fibroblasts (A, B) and keratinocytes (C, D), respectively. Effect of Gap27 on migration of adult diabetic fibroblasts (E, G) and keratinocytes (F, H) in early (E, F) or late passages (G, H), respectively. Initial cell scratch width = 100%. Note that lower values of relative cell scratch width reflect higher speed of migration (n= 11; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, values represent mean ± S.E.M.).

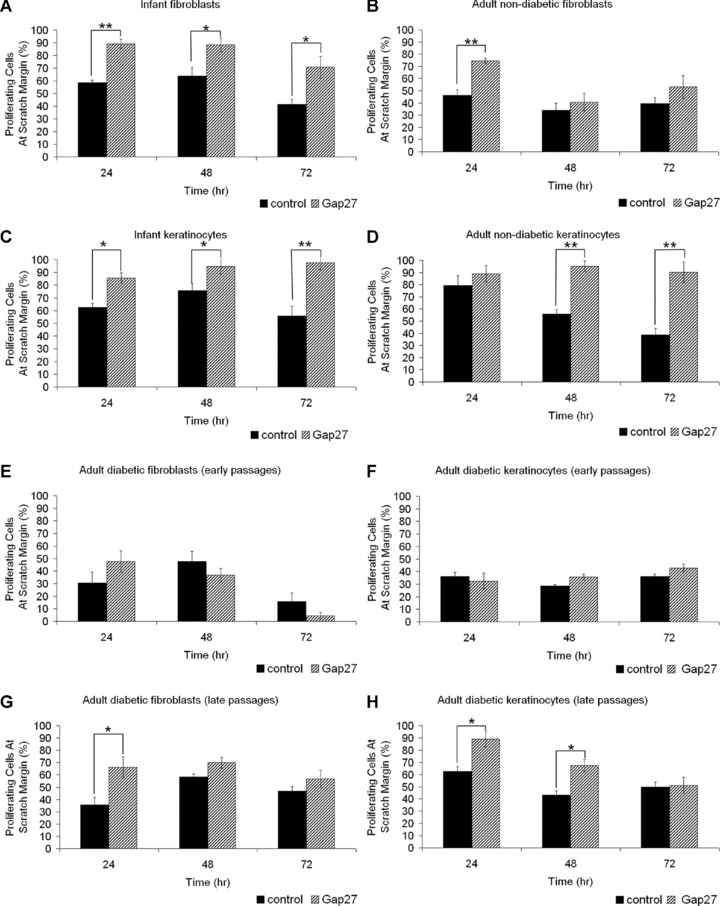

Furthermore the number of proliferative cells at the wound margins after scratch wounding was clearly increased in infant and adult non-diabetic fibroblasts and keratinocytes treated with Gap27 (Fig. 4A–D).

Fig 4.

Effect of 0.06 mM Gap27 on fibroblast and keratinocyte proliferation. Human primary infant and adult non-diabetic and adult diabetic fibroblasts and keratinocytes were grown to confluence on cover slips, scratch wounded and cultured in the presence of PBS or Gap27, respectively. Cover slips were fixed after 24, 48 and 72 hrs and immunostained for Ki67. The amount of proliferating cells at scratch margins was counted and normalized to the total amount of cells in the visual field. Effect of Gap27 on proliferation of (A, C) infant, (B, D) adult non-diabetic fibroblasts (A, B) and keratinocytes (C, D), respectively. Effect of Gap27 on proliferation of adult diabetic fibroblasts (E, G) and keratinocytes (F, H) in early (E, F) or late passages (G, H), respectively (n= 10; (fibroblasts) n= 14 (keratinocytes) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, values represent mean ± S.E.M.).

Diabetic cells are less susceptible to Gap27

Strikingly, migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes derived from diabetic donors, maintained in euglycaemic conditions, was less susceptible to treatment with 0.06 mM Gap27 in passages 2 to 5 (early passages, Fig. 3E, F). Increasing the dose of peptide to 0.6 mM had no effect on migration rates (data not shown). The same was true for lower concentrations (0.006 mM, data not shown). However, this observation changed during longer cultivation: In late passages (passages 12 to 15) exposure to 0.06 mM Gap27 also led to enhanced migration rates in cells of diabetic origin (Fig. 3G, H).

Similar results were observed for proliferation. Cell cultures of diabetic origin were less susceptible to Gap27 in early passages while proliferation significantly enhanced at scratch margins following treatment with Gap27 in late passages (Fig. 4E–H).

Cx43 protein levels, localization and phosphorylation is not altered in diabetic cells

To elucidate the putative causes for differences between non-diabetic and diabetic cells in early passages concerning cell migration and proliferation we investigated Cx43 protein levels, localization and phosphorylation status. Cx43 localization was reduced at wound margins in the 3D organotypic cultures (Fig. 5A, B) and in agreement with our previous work [6] a similar effect was seen in our ex vivo WHM (Fig. 5C). Following exposure to Gap27 this reduction at the wound margins in the WHM was maintained (Fig. 5D). Similar effects were seen in the organotypic models (not shown). Immunoflourescent analysis determined that the localization of Cx43 was the same in control and diabetic keratinocytes (Fig. 5E and F) and fibroblasts (not shown). Western blot analysis indicated similar levels of Cx43 protein expression between the different cell groups (Fig. 5G, H).

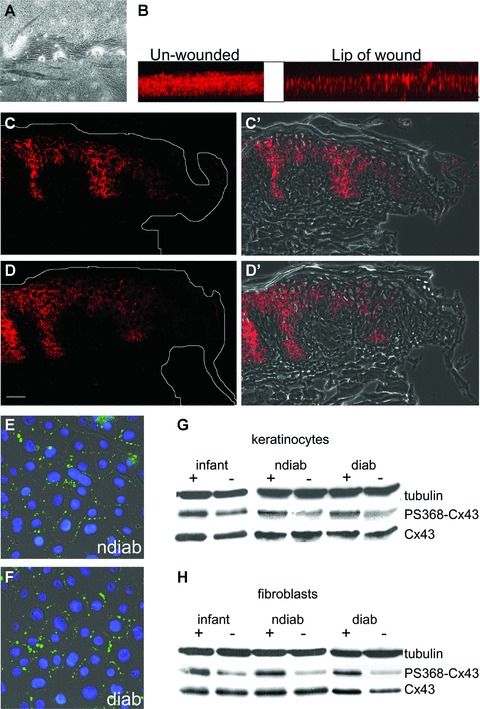

Fig 5.

Cx43 protein levels, localization and serine368-phosphorylation in organotypic cultures, ex vivo WHM and cell cultures. (A) Phase contrast image showing a scratch wound in a human organotypic model. (B) Z-stacks of Cx43 staining of unwounded and wounded organotypic models showing the natural Cx43-down-regulation at the lip of wound. (C, D) Effect of Gap27 on Cx43 localization in WHM. Immunofluorescence microscopy of porcine WHM showing the immunolocalization of Cx43 at the wound margins in the presence of PBS (C, C′) or 0.6 mM Gap27 (D, D′) 18 hrs after wounding [(C, D) epifluorescence; (C′, D′) overlay of epifluorescence and phase contrast pictures]. Note the down-regulation at wound margins in PBS- and Gap27-treated models (Scale bar = 50 μm). Immunolocalization of Cx43 in non-diabetic (E) and diabetic (F) keratinocyte cultures. Western blot analysis of (G) keratinocytes and (H) fibroblasts of different origin that were cultured in the presence (+) or absence (–) of 0.06 mM Gap27 for 24 hrs with antibodies specific for Cx43 and Cx43 phosphorylated at serine residue 368 (PS368-Cx43). Equal amounts of proteins were loaded and α-tubulin was used as gel loading control (representative blots of four replicated experiments). Note the similar amounts of Cx43 in cells of different origin and the influence of Gap27 on Cx43 phosphorylation while total amounts of protein were not altered (ndiab: non-diabetic adult cells, diab: diabetic adult cells).

Phosphorylation of the serine residue 368 on the carboxyl tail of Cx43 has previously been shown to be involved in GJIC [23, 24] and WH [25]. Indeed, application of Gap27 for 24 hrs resulted in an induction of Cx43 phosphorylation at serine residue 368 in non-diabetic cells of young and adult donors. However, this was also observed in diabetic cells (Fig. 5G, H).

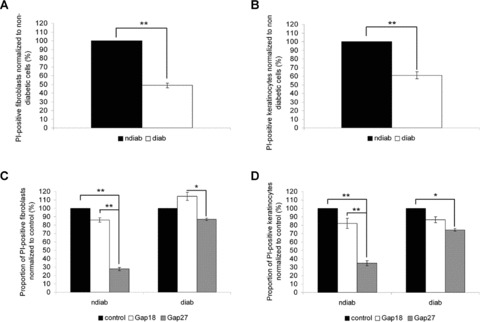

Diabetic cells show reduced hemichannel function

A significantly lower number of fibroblasts and keratinocytes of diabetic origin showed uptake of propidium iodide via Cx hemichannels in comparison to control cells (Fig. 6A, B). These results suggest that, despite similar Cx43 protein levels and localization of Cx43 at points of cell to cell contact, there are differences in hemichannel functionality between cells of different origin. Exposure of non-diabetic cells to Gap27 significantly reduced dye uptake compared to treatment with the control peptide Gap18, confirming hemichannel activity. By contrast dye uptake was only slightly reduced by treatment with Gap27 in cells of diabetic origin (Fig. 6C, D). Control experiments determined no significant changes for calcein and TRITC dextran staining (data not shown).

Fig 6.

Propidium iodide (PI) uptake in keratinocytes and fibroblasts of non-diabetic and diabetic origin. Proportion of PI+ fibroblasts (A) and keratinocytes (B) of different origin normalized to the amount of PI+ cells of non-diabetic origin (ndiab: non-diabetic cells, diab: diabetic cells). Proportion of PI+ fibroblasts (C) and keratinocytes (D) of different origin after treatment with 0.06 mM Gap18 or 0.06 mM Gap27, respectively, normalized to the amount of PI+ untreated control cells (n= 9, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, values represent mean ± S.E.M.).

Discussion

In the present work we show for the first time that the Cx43 mimetic peptide Gap27 enhances wound closure of 3D tissues, i.e. in vitro organotypic models and ex vivo WHM of higher mammals and inhibits connexin mediated dye spread in WHM. Additionally, Gap27 increases not only human infant but also adult keratinocyte and fibroblast migration. Furthermore, we also demonstrate an effect of Gap27 on skin cell proliferation ex vivo and in vitro. Surprisingly, cells derived from diabetic patients showed an impaired susceptibility to Gap27 treatment resulting in little change in migration or proliferation in the early passages of cultures, revealing putative differences in the role of Cx43 in wound repair in diabetic and non-diabetic cells.

Gap27 accelerates wound closure in WHM and enhances cell proliferation and migration

The acceleration of wound closure in human organotypic models and porcine/human WHM after application of Gap27 reinforces our previous 2D in vitro findings in human and mouse keratinocytes and fibroblasts [12, 15]. Further, this data fits well with findings of Qiu et al. and Mori et al. who treated wounds in mouse skin with Cx43-specific antisense gel and observed enhanced wound closure [9, 10]. Additionally, Cx43-deficient mice have been shown to exhibit accelerated wound closure compared to wild-type controls [11]. These results indicate that, despite the difference in epidermal Cx expression profiles that exists between species [26, 27], down-regulation of Cx43 function is universally important for WH.

To identify putative mediators for accelerated WH following Gap27 treatment, we investigated cell proliferation and migration events. We observed an increased number of proliferating keratinocytes in the regenerating epidermis of Gap27-treated WHM. In addition, we found elevated numbers of proliferative cells at margins of scratch wounds of infant and adult keratinocytes and fibroblasts treated with Gap27. The peptide did not affect the proliferation of cells distant from the wound in WHM, indicating that observations were specific and not due to culture conditions. Gap27 also enhanced Ki67 staining in mouse epidermal models (Martin et al., unpublished observations). The present data also agree with Mori et al. showing that the application of Cx43 antisense gel leads to enhanced keratinocyte proliferation in the regenerating epidermis of mice [10].

In order to specifically address Gap27 effects on migration, cells were cell cycle arrested. Enhanced migration occurred in both infant and adult skin cells following exposure to Gap27. Similar effects have previously been reported in non-proliferation inhibited human foreskin keratinocytes and fibroblasts treated with Gap27 [10, 12] and a non proliferation-inhibited murine fibroblast cell line (3T3 cells) treated with Cx43 antisense gel [10]. These data further re-enforce the concept that connexin mediated signalling events play an important role in modulating cell movement. Indeed, Cx43 has recently been shown to be directly involved in cell migration by mediating adhesion of neuronal cells [28]. The impact of Gap27 on mediating such events remains to be explored.

Taken together with other published data our data show that both, targeting Cx43 at the RNA-expression level and at the protein-function level, results in increased proliferation and migration and that Gap27 influences adult as well as infant cells.

Gap27 influences Cx43-Ser368-phosphorylation and hemichannel function but not expression and localization

In order to elucidate the molecular mechanism of Gap27 action in human skin cells we investigated its impact on Cx43 protein expression and localization, phosphorylation status and hemichannel activity. Protein levels and the spatial localization of Cx43 were not influenced by Gap27, agreeing with previous reports in vascular cells and murine and human keratinocytes [14, 15]. This suggests that down-regulation of Cx43 mediated signalling events but not loss of the protein is important for normal WH, irrespective of the cell type and species.

Dynamic changes in the phosphorylation status of Cx43 at serine residue 368 were demonstrated to be associated with WH: 24 hrs following scratch wounding a dramatic increase in Ser368 phosphorylation is reported to occur in proliferating human foreskin keratinocytes near to the wound edge [23, 25]. In the present work we show that exposure of both fibroblasts and keratinocytes to Gap27 for up to 48 hrs enhanced cell proliferation at wound margins. In monolayer cultures of infant and adult keratinocytes and fibroblasts of non-diabetic origin this correlated with enhanced Ser368 phosphorylation. This novel observation suggests a further mode of action of Gap27 peptide and may be important as phosphorylation of serine 368 is associated with specific cell growth mediated events and the functional status of GJ channels [29]. Thus, the Ser368 phosphorylation observed here may provide a further explanation for the effect of Gap27 on GJIC in skin cells that we previously reported [12, 15].

However, evidence continues to emerge that Cxs are also directly involved in controlling cell growth, death, differentiation and gene expression in a GJIC independent manner [30, 31]. It is well established that connexin mimetic peptides block CxHcs faster than GJ channels [2]. Accordingly, we looked for an effect of Gap27 on hemichannel function. Indeed Gap27 profoundly reduced hemichannel function in non-diabetic cells. Thus, Cx43-mimetic peptide Gap27 influences Cx43 channel and hemichannel function in non-diabetic skin cells.

Diabetic and non-diabetic cells have different susceptibilities to Gap27

We observed clear differences in the susceptibility of diabetic keratinocytes and fibroblasts to Gap27 compared to cells of non-diabetic origin. Peptide treatment did not lead to enhanced migration and proliferation in cells derived from diabetic patients, suggesting a ‘diabetic phenotype’ in these cells. Prolonged cultivation increased their susceptibility to Gap27 to the extent that was comparable to that of non-diabetic cells. These observations suggest that diabetic cells exhibit a memory of their origin but loose this phenotype over time in culture. This is also supported by the observation that cells of diabetic origin in early passages showed strongly reduced proliferation in comparison to non-diabetic cells while in later passages this phenomenon was less pronounced. An influence of diabetic origin on the behaviour of fibroblasts and keratinocytes has been described before [32, 33]. It is thought that systemic alterations such as hyperglycaemia and impaired insulin signalling may be directly involved in the development of chronic complications of diabetes by impairing glucose utilization, proliferation and differentiation of skin cells [34]. Indeed these factors need to be considered when ultimately defining peptide efficacy.

Seeking explanations concerning the altered susceptibility of diabetic versus non-diabetic cells to Gap27 treatment we investigated Cx43 protein levels, localization and phosphorylation at serine-residue 368 and hemichannel function. Akin to mRNA levels [33], Cx43 protein levels were similar in diabetic and non-diabetic cells and were not changed by Gap27 treatment. In addition, we also observed an up-regulation of Ser368-phosphorylation by Gap27 in diabetic cells comparable to non-diabetic cells. This suggests that phosphorylation-mediated alteration of GJIC is not the (only) cause for Gap27 influence on cell migration and proliferation in non-diabetic cells and that it does not account for the differences observed between diabetic and non-diabetic cells. Indeed, Abdullah et al. showed even higher rates of GJIC in human skin fibroblasts of diabetic origin which demonstrates the complexity of the system [35]. Therefore GJIC-independent causes must be taken into account. In fact, when focusing on hemichannel function we found decreased hemichannel permeability in diabetic keratinocytes and fibroblasts compared to non-diabetic cells. In addition, Gap27 which profoundly reduced hemichannel function in non-diabetic cells had only marginal impact in cells of diabetic origin. Therefore altered Cx43 hemichannel function might be one important cause for impaired susceptibility of diabetic cells for Gap27.

Implications for the treatment of (chronic) wounds with Gap27

Accelerating ‘normal’ acute WH could be clinically relevant for example in conditions of cosmetic surgery, since treatment with Cx43 specific antisense DNA has been shown to be associated with reduced scarring as well as accelerated WH [10, 36]. Another putative application area may be burn wounds, especially when covering large areas, because an accelerated healing of these wounds should reduce complications such as infections.

Since Cx43 expression is not down-regulated at chronic wound margins [6] it is tempting to suggest that targeting of Cx43 with Gap27 could also be a new and promising approach for the treatment of chronic wounds. This is further supported by our findings that application of Gap27 is not only beneficial for human infant skin cells but also for adult cells, which is of importance as patients with chronic wounds are usually older. Future work will need to carefully consider how to apply the peptide to an open wound. In recent reports, Mori et al. have successfully applied Cx43 specific antisense DNA to wounds embedded in a pluronic gel. An approach similar to this is envisaged [10].

However, our results suggest a limitation of Gap27 treatment for diabetic wounds and open intriguing questions of the role of Cx43 in diabetic WH. Further studies simulating the diabetic environment by culturing cells in hyperglycaemic/insulinaemic conditions may further elucidate these effects. It has been shown for other cell types, including cardiovascular cells, microvascular and retinal endothelial cells, that Cx43 expression, phosphorylation, functionality and degradation is altered under different glucose conditions [37–39] and preliminary results confirm this also for cultured keratinocytes and fibroblasts (data not shown). Diabetic hyperglycaemia is reported to directly affect the motility of keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts, and further contributes to impaired WH and ulceration by glycation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, inhibiting cellular migration and sensitising fibroblasts to growth factors [40]. The mechanism of diabetic resistance to Gap27 is currently unknown and is subject to future studies. It may be that the peptides are less stable in the diabetic environment or that altered Cx signalling within this environment is involved in the delayed response. Additionally, we have evidence that the peptides have differential effects on gene expression profiles in cells grown under normal or diabetic conditions. This work is part of an extensive further study.

Besides the observed limitations, a benign and reversible peptide treatment that impacts on a localized environment without chronically inhibiting protein expression levels nevertheless remains an attractive therapeutic option. Interestingly, Wang and co-workers (2007) showed that WH can be accelerated by a Cx43-specific antisense gel in streptotocin-induced diabetic rats [8]. One explanation for the positive influence of Cx43 antisense gel in these rats compared to the absent effectiveness of targeting of Cx43 by Gap27 in our experiments may be differences in the mode of action. Antisense gel affects the Cx43 expression directly whereas connexin mimetic peptides do not change the protein level of Cx43 but alter connexin mediated signalling events that can modify cellular behaviour. Future experiments shall clarify this possibility.

Summarizing our results, we continue to propose connexin mimetic peptides to be a promising approach for the treatment of acute and chronic non-diabetic wounds in the future. Taken together our results suggest that the permeability of Cx43-composed GJs and/or hemichannel signalling at the wound margins are crucial for progress of normal WH. However, the fact that under our experimental conditions beneficial effects of Gap27 in human cells of diabetic origin were less pronounced suggests a limitation. The role of Cx43 in diabetic WH events require a specific focus before such peptides, or stable analogues thereof can be deemed suitable for the treatment of chronic diabetic wounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Buerger-Buesing Stiftung (R.L., J.B.) and the Chief Science Office, Scotland (grant no. CZB/4/606; P.M., C.W.). We thank Dr. Mike Edward (University of Glasgow) for coordinating skin sample supply.

References

- 1.Dobrowolski R, Willecke K. Connexin-caused genetic diseases and corresponding mouse models. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:283–95. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans WH, De Vuyst E, Leybaert L. The gap junction cellular internet: connexin hemichannels enter the signalling limelight. Biochem J. 2006;397:1–14. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chanson M, Derouette JP, Roth I, et al. Gap junctional communication in tissue inflammation and repair. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goliger JA, Paul DL. Wounding alters epidermal connexin expression and gap junction-mediated intercellular communication. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1491–501. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.11.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coutinho P, Qiu C, Frank S, et al. Dynamic changes in connexin expression correlate with key events in the wound healing process. Cell Biol Int. 2003;27:525–41. doi: 10.1016/s1065-6995(03)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandner JM, Houdek P, Husing B, et al. Connexins 26, 30, and 43: differences among spontaneous, chronic, and accelerated human wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1310–20. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajpai S, Shukla VK, Tripathi K, et al. Targeting connexin 43 in diabetic wound healing: future perspectives. J Postgrad Med. 2009;55:143–9. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.48786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CM, Lincoln J, Cook JE, et al. Abnormal connexin expression underlies delayed wound healing in diabetic skin. Diabetes. 2007;56:2809–17. doi: 10.2337/db07-0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu C, Coutinho P, Frank S, et al. Targeting Connexin 43 Expression accelerates the rate of wound repair. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori R, Power KT, Wang CM, et al. Acute downregulation of connexin43 at wound sites leads to a reduced inflammatory response, enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and wound fibroblast migration. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:5193–203. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kretz M, Euwens C, Hombach S, et al. Altered connexin expression and wound healing in the epidermis of connexin-deficient mice. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3343–452. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright CS, van Steensel MA, Hodgins MB, et al. Connexin mimetic peptides improve cell migration rates of human epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts in vitro. Wound RepairRegen. 2009;17:240–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans WH, Boitano S. Connexin mimetic peptides: specific inhibitors of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:606–12. doi: 10.1042/bst0290606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin PE, Wall C, Griffith TM. Effects of connexin-mimetic peptides on gap junction functionality and connexin expression in cultured vascular cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:617–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandyba EE, Hodgins MB, Martin PE. A murine living skin equivalent amenable to live-cell imaging: analysis of the roles of connexins in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1039–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu SC, Driver VR, Wrobel JS, et al. Foot ulcers in the diabetic patient, prevention and treatment. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:65–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oviedo-Orta E, Errington RJ, Evans WH. Gap junction intercellular communication during lymphocyte transendothelial migration. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:253–63. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2001.0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rheinwald JG, Green H. Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: the formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells. Cell. 1975;6:331–43. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(75)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandner JM, Houdek P, Quitschau T, et al. An ex-vivo model to evaluate dressings & drugs for wound healing. Example: influence of lucilia sericata extracts on wound healing progress. EWMA J. 2006;6:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contreras JE, Sanchez HA, Eugenin EA, et al. Metabolic inhibition induces opening of unapposed connexin 43 gap junction hemichannels and reduces gap junctional communication in cortical astrocytes in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012589799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braet K, Aspeslagh S, Vandamme W, et al. Pharmacological sensitivity of ATP release triggered by photoliberation of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate and zero extracellular calcium in brain endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2003;197:205–13. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schalper KA, Palacios-Prado N, Orellana JA, et al. Currently used methods for identification and characterization of hemichannels. Cell Commun Adhes. 2008;15:207–18. doi: 10.1080/15419060802014198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampe PD, TenBroek EM, Burt JM, et al. Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1503–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solan JL, Fry MD, TenBroek EM, et al. Connexin43 phosphorylation at S368 is acute during S and G2/M and in response to protein kinase C activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2203–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richards TS, Dunn CA, Carter WG, et al. Protein kinase C spatially and temporally regulates gap junctional communication during human wound repair via phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:555–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richard G. Connexins: a connection with the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2000;9:77–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2000.009002077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salomon D, Masgrau E, Vischer S, et al. Topography of mammalian connexins in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:240–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12393218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elias LA, Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Gap junction adhesion is necessary for radial migration in the neocortex. Nature. 2007;448:901–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solan JL, Lampe PD. Connexin43 phosphorylation: structural changes and biological effects. Biochem J. 2009;419:261–72. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Sinovas A, Cabestrero A, Lopez D, et al. The modulatory effects of connexin 43 on cell death/survival beyond cell coupling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:219–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kardami E, Dang X, Iacobas DA, et al. The role of connexins in controlling cell growth and gene expression. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:245–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerman OZ, Galiano RD, Armour M, et al. Cellular dysfunction in the diabetic fibroblast: impairment in migration, vascular endothelial growth factor production, and response to hypoxia. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:303–12. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63821-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandner JM, Zacheja S, Houdek P, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases, cytokines, and connexins in diabetic and nondiabetic human keratinocytes before and after transplantation into an ex vivo wound-healing model. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:114–20. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spravchikov N, Sizyakov G, Gartsbein M, et al. Glucose effects on skin keratinocytes: implications for diabetes skin complications. Diabetes. 2001;50:1627–35. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdullah KM, Luthra G, Bilski JJ, et al. Cell-to-cell communication and expression of gap junctional proteins in human diabetic and nondiabetic skin fibroblasts: effects of basic fibroblast growth factor. Endocrine. 1999;10:35–41. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:10:1:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coutinho P, Qiu C, Frank S, et al. Limiting burn extension by transient inhibition of Connexin43 expression at the site of injury. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:658–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoguchi T, Yu HY, Imamura M, et al. Altered gap junction activity in cardiovascular tissues of diabetes. Med Electron Microsc. 2001;34:86–91. doi: 10.1007/s007950170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato T, Haimovici R, Kao R, et al. Downregulation of connexin 43 expression by high glucose reduces gap junction activity in microvascular endothelial cells. Diabetes. 2002;51:1565–71. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandes R, Girao H, Pereira P. High glucose down-regulates intercellular communication in retinal endothelial cells by enhancing degradation of connexin 43 by a proteasome-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27219–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peppa M, Stavroulakis P, Raptis SA. Advanced glycoxidation products and impaired diabetic wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:461–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]