Abstract

This paper describes a community-based participatory research program with Alaska Native people addressing a community need to reduce tobacco use among pregnant women and children. Tobacco use during pregnancy among Alaska Native women is described along with development of a community partnership, findings from a pilot tobacco cessation intervention, current work, and future directions. Among Alaska Native women residing in the Yukon Kuskokwim Delta region of western Alaska, the prevalence of tobacco use (cigarette smoking and/or use of smokeless tobacco) during pregnancy is 79%. Results from a pilot intervention study targeting pregnant women indicated low rates of participation and less than optimal tobacco abstinence outcomes. Developing alternative strategies to reach pregnant women and to enhance the efficacy of interventions is a community priority, and future directions are offered.

Keywords: Nicotine, Tobacco, Intervention, Pregnancy, Alaska native

Introduction

This paper describes a community-based participatory research program with Alaska Native people addressing a community need to reduce tobacco use among pregnant women and children. Tobacco use during pregnancy among Alaska Native women [cigarette smoking and/or use of smokeless tobacco (ST)] is described along with development of a community partnership, findings from a pilot cessation intervention, current work, and future directions.

Tobacco Use Among Alaska Native Pregnant Women

Tobacco use during pregnancy is a major public health problem in the USA. In the USA the prevalence of cigarette smoking during pregnancy is 14% with the highest rates observed for Alaska Native (36%) and American Indian (21%) women [1]. Prenatal use of ST is <0.05% among US women [2]. However, the use of noncigarette forms of tobacco including homemade forms of ST is prevalent or gaining in popularity in many parts of the world among girls and women of reproductive age, with estimates of prenatal ST use ranging from 6% to 17% [3, 4]. Both cigarette smoking [5, 6] and ST use [7–10] during pregnancy pose substantial risks to maternal and fetal health.

The adverse effects of tobacco use on maternal and infant health outcomes are especially relevant for populations with a high prevalence of tobacco use such as Alaska Native people [11]. In 2007, in Alaska, the prevalence of current smoking (38% vs. 19%) and ST use (13% vs. 4%) was higher among Alaska Native adults compared with nonnative people [12]. Using the Alaska Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data, among Alaska women who delivered a live birth in 2003, the prevalence of ST use, cigarette smoking, and any tobacco use during pregnancy was 17%, 26%, and 41% for Alaska Native women compared with 0.4%, 15%, and 16% for White women, respectively [13]. Prenatal ST use among Alaska Native women was higher for those residing in the western region of Alaska where nearly 60% of women used ST. Similarly, among 832 Alaska Native women from the Yukon Kuskokwim (Y-K) Delta region of western Alaska and enrolled in the WIC program, we found that 48% used tobacco in the 3 months before pregnancy, 79% reported prenatal tobacco use, and 70% used tobacco at 6 weeks postpartum [14]. During pregnancy, 37% reported ST use only, 19% smoked cigarettes exclusively, 23% used both, and 21% reported neither. In addition, pregnancy appears to be a high-risk period for initiation of tobacco use; of the 432 women reporting no use of tobacco 3 months before pregnancy, 324 (75%) reported prenatal tobacco use, of which 78% used ST exclusively.

The Y-K Delta region has a total population of 25,000, and Alaska Natives of this region are of Yup’ik or Cup’ik ethnicity. A common form of ST used is Iqmik, a mixture of tobacco leaves and fungus ash [15]. This homemade ST product may result in higher maternal and fetal nicotine exposure than use of other tobacco products [16]. The addition of ash raises the pH of the tobacco, increasing the amount of free (unionized) nicotine available for absorption thus enhancing its addictive properties [15], and increasing the available levels of carcinogens [17]. Our focus group works with pregnant women, and other Alaska Native adults suggest that Iqmik is perceived as safer to use during pregnancy than other tobacco products [18]. One reason why Iqmik is perceived as safer is because it contains “natural” ingredients, e.g., ash.

The high prevalence of tobacco use during pregnancy suggests that cessation interventions targeting Alaska Native women are a public health priority [19]. Although several decades of research have focused on interventions for pregnant smokers, except for our pilot work [20] interventions evaluated among AI/AN pregnant women do not exist [21, 22]. The updated clinical practice guideline [22] highlighted the need for development of effective interventions and delivery strategies for pregnant tobacco users generally and especially populations that carry a disproportionate burden from tobacco such as AI/AN women.

Development and Continuation of a Successful Community Partnership

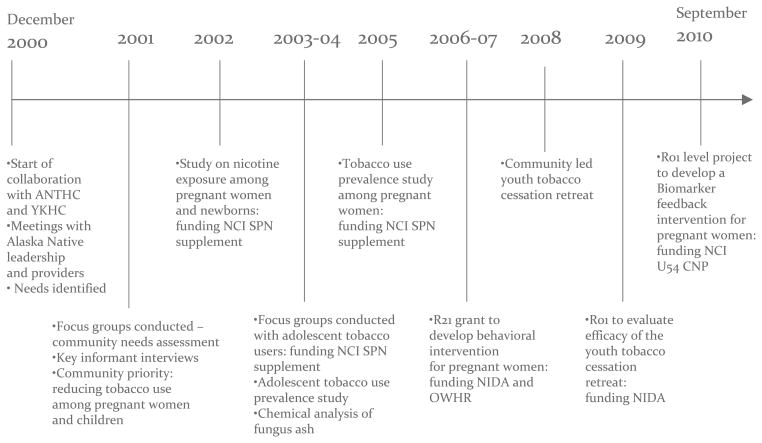

We learned through focus groups [18] that the health and welfare of the children is paramount to the Y-K Delta Alaska Native community. Together with the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation (YKHC) and Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) Board, the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center developed a long-term plan to address this community need. Our work together over the past 10 years has focused on development of programs to reduce tobacco use among pregnant women and children. Figure 1 shows the timeline over which the partnership was developed, and it continues to be a successful collaboration.

Fig. 1.

Development of partnership—timeline

In December of 2000, potential partners from the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center met with Alaska Native leadership at the ANTHC in Anchorage and at the YKHC in Bethel to discuss community needs relevant to tobacco use. Next, 12 focus groups were conducted in the Y-K Delta region to assess community needs, interest in stopping tobacco use, and preferences for cessation interventions. Four of the 12 focus groups were conducted with pregnant women and two with adolescent tobacco users. Since then, our research has focused on examining the prevalence of tobacco use among Y-K Delta pregnant women [14] and among adolescents [23], conducting qualitative work among adolescent tobacco users to assess intervention preferences [24], and development and pilot testing of a tobacco cessation intervention for pregnant women [20, 25]. Currently, with funding from NIDA, a study is ongoing that involves development and pilot testing of a tobacco cessation program for Y-K Delta Alaska Native youth (R01 DA 025156). A recently funded study through the NCI Community Networks Program (U54 CA153605, PI: Dr. Judith Kaur) will develop and examine the efficacy of a biomarker feedback intervention for Alaska Native pregnant women seen at the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage. This study will involve collaboration between the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center with the ANTHC and Southcentral Foundation.

Pilot Intervention During Pregnancy for Alaska Native Women

We learned in our prior focus group study [18] that personal stories from Y-K Delta Alaska Native people were seen as an acceptable and potentially effective intervention component in addition to education on the adverse effects of Iqmik use. Two important learning mechanisms among Alaska Native people are role modeling and storytelling [26]. Storytelling has been used to preserve traditions of the AI/AN culture, overcome cultural barriers to health behavior change [27, 28], and serve as social modeling and teaching tools [29].

Based on our qualitative findings, we developed a targeted tobacco cessation intervention for Y-K Delta pregnant women [20]. As part of the treatment development process, individual interviews and focus groups were conducted with pregnant women and family members to obtain feedback on the intervention components. The intervention included counseling by an Alaska Native counselor based on the five As along with pregnancy and culturally specific self-help materials, a state of the art tobacco cessation intervention for pregnant women [22]. The five As are: ask about tobacco use, assess the woman’s interest in quitting, advise the woman to quit, assist the woman in quitting, and arrange for follow-up and were adapted to be culturally appropriate. Counseling was conducted at the first prenatal visit lasting 15–25 min and at four 10–15-min telephone follow-up calls. The intervention also included a video of personal stories of pregnant women or women who had children as well as family members that was filmed in the Y-K Delta region. Based on a social cognitive theoretical framework [30], the women served as role models to reinforce self-efficacy and positive outcome expectancies of quitting tobacco for the pregnant woman, her baby, and her family. Women explained how they quit tobacco using positive cultural activities such as berry picking. Family members and other community members on the video reinforced the women for remaining tobacco free.

The intervention was evaluated in a pilot randomized trial with the control condition comprising brief (5 min) counseling at the first prenatal visit using the five As. Recruitment occurred over 8 months with a target sample size of 60 women. Incentives were not offered for participation, but those enrolled received remuneration for completion of the follow-up assessment in late pregnancy (week 36 gestation). Prenatal care and WIC providers referred the woman to the study coordinator located at the Nicotine Control and Cessation Program if she was a current tobacco user, ≤24 weeks pregnant, and interested in participating.

A total of 293 women were identified as potentially eligible and referred, with >24 weeks gestation being the most common reason for ineligibility. Of those referred, 81 (28%) did not keep their appointment and 212 (72%) were screened. Of those screened, about half (54%, n=114) were ineligible because they reported not using tobacco, 59 (28%) were not interested in participating, 4 (2%) were excluded based on other eligibility criteria, and the remaining 35 women (16%) provided consent and were enrolled. Among the 59 “not interested,” reasons cited for nonparticipation were not ready to quit and lack of time to complete the counseling at the visit due to the need to catch the scheduled flight back to their village. However, when the study coordinator offered to conduct the counseling by telephone, participation did not increase.

Participants rated the intervention as highly acceptable, and retention was good with 83% completing the follow-up in late pregnancy. However the biochemically verified abstinence rates were not optimal (0% for the intervention, 6% among the controls). We concluded that alternative approaches are needed to enhance the reach to pregnant women and improve the efficacy of interventions.

Current Work and Future Directions

The low rate of participation in our pilot intervention suggested that the program was not feasible or acceptable to pregnant women. Continued efforts to reduce tobacco use among pregnant women are an essential component of a regional plan to significantly improve maternal and infant health. Next steps include qualitative work to explore options for attracting women to cessation programs and cultural beliefs and other reasons surrounding Iqmik and other tobacco use during pregnancy. In addition, women’s preconceptions about research should be explored. Of interest was the finding that about half of pregnant women screened for our pilot intervention study stated they did not use tobacco, even though they reported using tobacco on the same day to their provider. In addition, 28% of referred women did not show to their appointment with the study coordinator. Anecdotal reports from the women who did not participate indicated there was perceived stigma associated with attending the Nicotine Control and Cessation Program. To reduce the perceived stigma of tobacco use as an enrollment barrier, future studies could consider addressing tobacco use within the context of traditional health and wellness or “healthy pregnancies.” There is some evidence that interventions focused on lifestyle or wellness enhances participation among pregnant tobacco users [31, 32] and increases effectiveness for smoking cessation during pregnancy [33] and the postpartum period [34]. With a focus on health and wellness, nontobacco users could be enrolled to reduce the perceived stigma of study participation and also because many start using tobacco in pregnancy.

Our prior work indicates women are seen for their first prenatal visit relatively late in pregnancy with about 44% seen in the third trimester [14], and most women were ineligible for our pilot intervention because they were at >24 weeks gestation. Thus, research could explore recruitment of women at the time of the pregnancy test that is done by village-based health aides to reach women earlier in pregnancy. A positive pregnancy test could be an opportune time to offer an intervention for women irrespective of their current tobacco use status and would reduce barriers associated with lack of time to complete the intervention at prenatal care visits. In addition, tobacco control efforts targeting the entire community, not just pregnant women, may yield greater reductions during pregnancy. For example a community-wide social marketing campaign could be developed to address tobacco use in pregnancy [33]. There are also opportunities to utilize elders and other local community members to promote tobacco cessation, i.e., through community presentations and providing individual support to pregnant women [35].

The perception that ST use is safer during pregnancy than cigarette smoking [18] may account for the high initiation of ST use among women reporting nontobacco use 3 months prior to pregnancy [14] and could have posed barriers to participation and successful quitting in our pilot intervention. In addition, the most frequently recommended enhancement to the intervention among our pilot participants was to provide more objective information on the risks of Iqmik/ST use for the baby. A current study based at the Alaska Native Medical Center will document fetal nicotine and carcinogen exposure among pregnant cigarette smokers and ST users (U54 CA153605). The project will enroll 150 maternal–infant pairs with assessments conducted during pregnancy and at delivery. The infant’s exposure to the tobacco specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamine)-1-(3-pyndyle)-1-butanone (NNK) will be assessed. NNK is a potent carcinogen, thought to contribute to lung and pancreatic cancer [36]. NNK is a likely contributor to oral cancer in ST users and induces oral tumors in rats [37]. Information of this type may be useful in motivating Alaska Native pregnant women to avoid tobacco use during pregnancy. Based on the biomarker findings, we will develop and test a novel biomarker feedback intervention relating cotinine concentrations in the urine of pregnant women with the woman and infant’s likely exposure to NNK on tobacco cessation outcomes in late pregnancy

In summary, through development of a successful partnership, a great deal of progress has been made in the past 10 years toward developing interventions to reduce tobacco use among Alaska Native pregnant women. This worked included assessing community needs and intervention preferences, documenting tobacco use prevalence, and development and testing of a pilot tobacco cessation intervention. Ongoing and planned future studies should yield additional findings that will advance the science and reduce health disparities in these communities.

Acknowledgments

From the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation (YKHC) in Bethel, Alaska, I would like to thank the staff at the Nicotine Cessation and Control Program, Women’s Health Department and Obstetrical, WIC and Community Health Aide Program for their support with the research conducted over the past 10 years. I also acknowledge Dr. Joseph Klejka, Mr. Gene Peltola, and the YKHC Board for their continued support of the team’s work on tobacco use in the region. From the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, I acknowledge the important contributions to this work of Caroline Renner, MPH and Dr. Anne Lanier. In addition, I acknowledge the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center leadership for their support and our research team at Mayo Clinic and at the YKHC for their dedication and commitment to this work. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, supplements to National Cancer Institute grant U01 CA86098 awarded to Judith Kaur, MD; National Cancer Institute grant U54 CA153605 awarded to Judith Kaur, MD; National Institute on Drug Abuse and Office of Women’s Health Research grant R21 DA19948 awarded to Dr. Patten; and National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01 DA 025156 awarded to Dr. Patten.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The author declares that she does not have a conflict of interest.

This paper is based on an oral presentation delivered at the “8th National Changing Patterns of Cancer in Native Communities: Strength Through Tradition and Science” conference, Seattle, Washington, September 2010.

References

- 1.Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. Trends in smoking before, during and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000–2005. MMWR. 2009;58(4):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timberlake DS, Huh J. Demographic profiles of smokeless tobacco users in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloch M, Althabe F, Onyamboko M, Kaseba-Sata C, Castilla EE, Freire S, Garces AL, et al. Tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy: an investigative survey of women in 9 developing nations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1833–1840. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.England L, Kim SY, Tomar SL, Ray CS, Gupta PC, Eissenberg T, Cnattingius S, Bernet JT, Tita AT, Winn DM, Djordjevic MV, Lambe M, Stamilio D, Chipato T, Tolosa JE. Non-cigarette tobacco use among women and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(4):454–64. doi: 10.3109/00016341003605719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S125–140. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Women and smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. 2001 Accessed at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2001/index.htm.

- 7.Steyn K, de Wet T, Saloojee Y, Nel H, Yach D. The influence of maternal cigarette smoking, snuff use and passive smoking on pregnancy outcomes: the Birth To Ten Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20(2):90–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.England LJ, Levine RJ, Mills JL, Klebanoff MA, Yu KF, Cnattingius S. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in snuff users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):939–943. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta PC, Subramoney S. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of stillbirth: a cohort study in Mumbai, India. Epidemiology. 2006;17(1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000190545.19168.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wikstrom AK, Cnattingius S, Stephansson O. Maternal use of Swedish snuff (snus) and risk of stillbirth. Epidemiology. 2010;21 (6):772–778. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f20d7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JJ, Ferucci ED, Dillard DA, Lanier AP. Tobacco use among Alaska Native people in the EARTH study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(8):839–844. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. Health risks in Alaska among adults: Alaska Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (BRFSS) 2007 annual report. Alaska Department of Health and Social Services; Anchorage: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, England L, Dietz PM, Morrow B, Perham-Hester KA. Prenatal cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among Alaska native and white women in Alaska, 1996–2003. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(5):652–659. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patten C, Renner CC, Decker PA, O’Campo E, Larsen K, Enoch C. Tobacco use and cessation among pregnant Alaska Natives from Western Alaska enrolled in the WIC Program. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(Suppl 1):30–36. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0331-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renner CC, Enoch C, Patten CA, Ebbert JO, Hurt RD, Moyer TP, Provost EM. Iqmik: a form of smokeless tobacco used among Alaska natives. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(6):588–594. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.6.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurt RD, Renner CC, Patten CA, Ebbert JO, Offord KP, Schroeder DR, Enoch CC, Gill L, Angstman SE, Moyer TP. Iqmik—a form of smokeless tobacco used by pregnant Alaska Natives: nicotine exposure in their neonates. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;17(4):281–289. doi: 10.1080/14767050500123731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappas RS, Stanfill SB, Watson CH, Ashley DL. Analysis of toxic metals in commercial moist snuff and Alaskan iqmik. J Anal Toxicol. 2008;32(4):281–291. doi: 10.1093/jat/32.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renner CC, Patten CA, Enoch C, Petraitis J, Offord KP, Angstman S, Garrison A, Nevak C, Croghan IT, Hurt RD. Focus groups of Y-K Delta Alaska Natives: attitudes toward tobacco use and tobacco dependence interventions. Prev Med. 2004;38(4):421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SY, England L, Dietz PM, Morrow B, Perham-Hester KA. Patterns of cigarette and smokeless tobacco use before, during, and after pregnancy among Alaska Native and White women in Alaska, 2000–2003. Matern Child Health J. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patten CA, Windsor RA, Renner CC, Enoch C, Hochreiter A, Nevak C, Smith CA, et al. Feasibility of a tobacco cessation intervention for pregnant Alaska Native women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(2):79–87. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melvin C, Gaffney C. Treating nicotine use and dependence of pregnant and parenting smokers: an update. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 (Suppl 2):S107–124. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angstman S, Patten CA, Renner CC, Simon A, Thomas JL, Hurt RD, Schroeder DR, Decker PA, Offord KP. Tobacco and other substance use among Alaska Native youth in western Alaska. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(3):249–260. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patten C, Enoch C, Renner CC, Offord KP, Nevak C, Kelley S, Thomas J, et al. Focus groups of Alaska Native adolescent tobacco users: preferences for tobacco cessation interventions and barriers to participation. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(4):711–723. doi: 10.1177/1090198107309456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patten C, Enoch C, Renner CC, Larsen K, Decker PA, Anderson KJ, Nevak C, Glasheen A, Offord KP, Lanier A. Evaluation of a tobacco education intervention for pregnant Alaska Native women. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2008;2(3):33–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Lanier A, Dignan M. Using theater to promote cancer education in Alaska. J Canc Educ. 2005;20(1):45–48. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tom-Orme L. Native Americans explaining illness: storytelling as illness experience. In: Whaley BB, editor. Explaining illness: research, theory, and strategies. Erlbaum; Mahwah: 2000. pp. 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodge FS, Fredericks L, Rodriguez B. American Indian women’s talking circle. A cervical cancer screening and prevention project. Cancer. 1996;78(7 Suppl):1592–1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, Slater MD, Wise ME, Storey D, Clark EM, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(3):221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowry RJ, Hardy S, Jordan C, Wayman G. Using social marketing to increase recruitment of pregnant smokers to smoking cessation service: a success story. Public Health. 2004;118:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson SA, Miller YD, Watson B. The effects of a woman-focused, woman-held resource on preventive health behaviors during pregnancy: the pregnancy pocketbook. Women Health. 2010;50(4):342–358. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2010.498756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowry RJ, Billett A, Buchanan C, Whiston S. Increasing breastfeeding and reducing smoking in pregnancy: a social marketing success improving life chances for children. Perspect Public Health. 2009;129(6):277–280. doi: 10.1177/1757913908094812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Costello TJ, Li Y, Daza P, Mullen PD, Velasquez MM, Cinciripini PM, Cofta-Woerpel L, Wetter DW. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse among diverse low-income women: a randomized trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(4):326–335. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan MB, Bad Wound D, Tenney M, Vigil G. Native American Recruitment into Breast Cancer Screening: the NAWWA Project. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15:28–32. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hecht SS. Human urinary carcinogen metabolites: bio-markers for investigating tobacco and cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23 (6):907–922. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.6.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hecht SS. Tobacco smoke carcinogens and lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(14):1194–1210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.14.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]