Abstract

Aim

The present investigates deals with the change in the pharmacokinetic of Sildenafil citrate (SIL) in disease condition like diabetic nephropathy (DN).

Method

Diabetes was induced in rats by administering Streptozotocin i.e. STZ (60 mg/kg, IP) saline solution. Assessment of diabetes was done by GOD-POD method and conformation of DN was done by assessing the level of Creatinine, Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) and Albuminurea. After the conformation of DN single dose of drug SIL (2.5 mg/kg, p.o.) were given orally and Pharmacokinetic Parameters like [AUC o-t (ug.h/ml), AUC 0-∞, Cmax, Tmax, Kel, Clast] were estimated in the plasma by the help of HPLC-UV.

Result

There was significant increase (p < 0.01) in the Pharmacokinetic parameters of SIL in DN rat (AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, Cmax, Tmax and T1/2) compare to normal control rat and significant increase Kel in the DN rat compare to control rat.

Conclusion

The study concluded that there was significant (p < 0.01) increase in the bioavailability of SIL in DN.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Streptozotocin, Sildenafil citrate

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a complex endocrine metabolic disorder. Globally, as of 2010, an estimated 285 million people had diabetes, with type 2 making up about 90% of the cases [1]. Its incidence is increasing rapidly, and by 2030, this number is estimated to almost double [2]. India has more diabetics than any other country in the world, according to the International Diabetes Foundation [3]. Clinically, the main consequence of hyperglycemia is secondary impairments in various tissues and organs. Some complications such as cardio vascular disease, kidney disease, retinopathy, and nervous system diseases result in substantial morbidity and mortality [4]. What is especially note worthy that the pharmacokinetic parameters of many drugs are altered in diabetes [5-8]. The possible reasons for these pharmacokinetics changes are diverse and complex, including gastrointestinal lesions which cause changes in drug absorption [9]; changes in transporters responsible for uptake, efflux and elimination [10]; changes in liver drug enzymes which alters metabolic rate [11]; nephropathy which leads to changes of drug transport, metabolism and elimination [12]. However, the pharmacokinetic parameters of drugs are usually determined from healthy subjects. In clinical studies it has been reported that drug accumulated in some diabetic patients [13], and diabetes may influence pharmacodynamics and increase the adverse effect of hypoglycemic agents. Therefore, the study of drug pharmacokinetics in the diabetic state is important and beneficial for clinical development.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a progressive, irreversible disease characterized by increasing blood pressure, microalbuminuria, proteinuria, and a continuous decline in glomerular filtration rate [14]. There was number of drugs used in the management of DN. Sildenafil citrate (SIL), 1-[4-ethoxy-3-(6, 7-dihydro-1-methyl-7-oxo-3-propyl-1H- pyrazolo [4, 3-d] pyrimidin-5-yl) phenylsulfonyl] - 4 methylpiperazine, primarily indicated in the treatment of erectile dysfunction [15]. It acts by inhibiting cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase type 5, an enzyme that promotes degradation of cGMP, which regulates blood flow in the penis. Literature suggest phosphodiesterase inhibitors type 5 (Sildenafil citrate) having role in the management Diabetic Nephropathy So it is worthy to check the change in the pharmacokinetics of SIL in Diabetic complication like DN [16].

Material and methods

Animal

Healthy Male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–300 gm) were used for the pharmacological screening. The animals were housed in polypropylene cages with wire mesh top and husk bedding and maintained under standard environmental conditions (25 ± 20C, relative humidity 60 ± 5%, light- dark cycle of 12 hours each) and fed with standard pellet diet (Trimurti feeds, Nagpur) and water ad libitum, were used for the entire animal study. The rats were housed and treated according to the rules and regulations of CPCSEA and IAEC. The protocols for all the animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC). CPCSEA registration no.- (650/02/C/CPCSEA/08).

Instrumentation

A double beam UV-Visible spectrophotometer, model UV-2401 PC (Japan) with 10 mm matched quartz cell was used.

The HPLC instrument consisted of Thermo separation product quaternary gradient equipped with pump spectra system P-4000 having inline membrane degasser. Detector was a UV visible detector belonging to spectra system UV 1000. Rheodyne 9725 injector with 20 μl loop. All the data was processed using Data Ace software. Separation was achieved using a Prontosil C18 stationary phase (150 7× 4.6 mm i.d. 5 μm particle size) and The analytical column was protected by a Phenomenex C18 guard column (4 mm × 2.0 mm, i.d.).

Materials and reagents

Sildenafil citrate was donated by Ajanta Pharmaceuticals pvt. ltd. All the reagent and chemical used were of AR analytical & HPLC grade. Methanol (Spectrochem) and water (Lobachem) used were of HPLC grade.

Induction of diabetes

Diabetic rats were induced with an ip injection of 60 mg/kg of STZ (dissolved in pH 4.5 citrate buffer immediately before injection), while controlled normal rats (Control group, n = 6) received 2.5 mL/kg of citrate buffer. Induction of the diabetic state was confirmed by measuring the blood glucose level at the 72 h after the injection of STZ. Rats with more than 200 mg/dl Blood glucose level was conformation of diabetes. Blood glucose level and biomarkers of nephropathy were checked after 21 day for the conformation of Nephropathy. After the conformation of Diabetic Nephropathy single dose of drugs were given orally to the following groups and the blood glucose level were checked. Group I: Control group + SIL (2.5 mg/kg), Group II: Negative Control (STZ) + SIL (2.5 mg/kg).

Pharmacokinetic study

Single dose of SIL citrate was given orally to different groups of rat for Pharmacokinetic studies. The rats were fasted overnight with free access to water before administration of drugs. After a single oral administration of SIL (2.5 mg/kg, p.o.), 0.5 ml of blood samples were collected from retro orbital plexus sinus at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 h time-points. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at -20°C until analysis. Aliquots of 0.1 ml serum samples were processed on the developed HPLC Method which was developed in our lab [17].

The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated with a Non-Compartmental model using Kinetica TM Soft-ware (version 4.4.1 Thermo Electron Corporation, U.S.A). Each value is expressed as Mean ± SD.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism version 5.0 for Windows (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were statistically analyzed using Student t test.

Result

Table 1 shows that there was significant increase (p < 0.01) in the blood glucose level (289.66 ± 3.40), BUN (20.39 ± 1.52) and creatinine (1.255 ± 0.07) level in blood in STZ treated rat as compare to Control group. Whereas STZ treated group shows significant increase (p < 0.01) Albumin urea (266.7 ± 0.20) level in the urine compare to control group. These results confirm the nephropathy induction.

Table 1.

Effect of STZ on blood glucose level, Serum Creatinine, BUN and Albuminurea level in rats

| Sr. no. | Groups | Blood glucose level (mg/dl) | Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | BUN level (mg/dl) | Albuminurea (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Control |

108.00 ± 2.26 |

0.750 ± 0.07 |

10.89 ± 2.64 |

97.75 ± 0.25 |

| 2 | Negative control (STZ) | 289.66 ± 3.40@ | 1.255 ± 0.07@ | 20.39 ± 1.52@ | 266.7 ± 0.20@ |

Data are the mean ± SEM for 6 rats,

@p < 0.01 compare to normal Control.

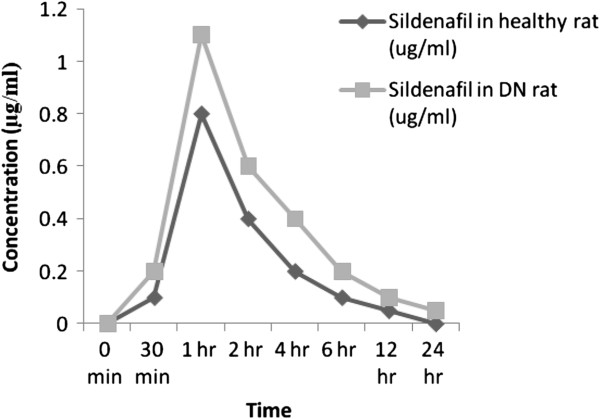

Table 2 shows that the effect of Diabetic Nephropathy on pharmacokinetic of SIL. The Pharmacokinetic parameters like AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, Cmax, Tmax, Kel and T1/2 were assessed. There were significant increase (p < 0.01) in the Pharmacokinetic parameters of SIL in DN rat (AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, Cmax, Tmax and T1/2) compare to normal control rat and significant increase Kel in the DN rat compare to control rat. Figure 1 shows the serum concentration-time profile of SIL after oral administration of 2.5 mg/kg of SIL in rats.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic variables of SIL after oral administration at the dose of 2.5 mg/kg to control rats and diabetic rat

| Sr. no. | Group | AUCo-t (ug.h/ml) | AUC 0-∞ (ug.h/ml) | C max (ug) | Tmax (hr) | Kel | T 1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Control + SIL (2.5 mg/kg) |

2.19 ± 0.052 |

0.5 ± 0.02 |

0.8 ± 0.05 |

1 hr |

0.10 ± 0.01 |

6.93 |

| 2 | STZ + SIL (2.5 mg/kg) | 3.72 ± 0.098* | 1.12 ± 0.09* | 1.1 ± 0.1* | 1 hrns | 0.089 ± 0.002* | 8.6* |

Data are the mean ± SEM for 6 rats,

*p < 0.01 compare to normal Control.

Figure 1.

Mean serum concentration-time profile of SIL after oral administration of 2.5 mg/kg of SIL in rats.

Discussion

In the present study type 1 diabetes was induced by the STZ in experimental rats [18] and the AUC and C max of SIL were compared with control rat. Diabetic Nephropathy was marked by increase in the Serum creatinine, Blood urea nitrogen in blood and albumin urea in urine [19]. In the present study diabetic nephropathy was conformed as there were significant increases in these values.

Sildenafil citrate is widely used as selective inhibitors of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-specific phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED) [20,21]. They can also be efficient as therapy for a range of cardiovascular diseases, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [22-24]. The major route of elimination of sildenafil is hepatic metabolism, with renal excretion of unchanged drug [25].

Diabetic patients have higher level of circulating glucose in the blood, leading to non-enzymatic glycation of several proteins including albumin. Glycated albumin exhibits atherogenic effects in various cells [26]. Non-enzymatic glycation of albumin produces conformational changes in the structure of albumin (affinity of the phenytoin binding site on albumin based on a modification of the lysine group) [27], which can increase the free fraction of acidic drugs in patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes (for more detail, see Table two) [28-35]. Worner et al. [28] reported a 50% decrease in binding of dansylsarcosine to albumin in diabetic patients, whereas the concentration of circulating albumin was the same in diabetic patients [36,37]. Glycation of blood and plasma proteins leads to reduction in protein binding capacity [38-40]. A linear relationship has been reported between the degree of albumin glycation and the unbound fraction of drug in the serum of diabetic patients. Thus, for highly albumin bound acidic compounds the reduction in the plasma serum protein binding capacity has been shown in diabetic patients [41].

In DN and Control rat single dose of SIL was given orally, and different pharmacokinetic parameters were assessed. As DN leads to decrease in the GFR [42] and protein content in the blood as there is microalbuminurea in DN. This may increase the bioavailability of SIL in DN rat. There was (Table 2) increase in the pharmacokinetic parameters like AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, Cmax, Tmax, Kel and T1/2 in DN rat compare to normal control rat.

Conclusion

Increase in the pharmacokinetic parameters of SIL confirms its increased bioavailability in DN rats.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. PMM: Performed the analysis of data, drafting and editing, Dr. AVC: Supervision, proof read and edited the manuscript. AST: principle investigator, wrote the proposal, conducted the study and did the initial drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Alok S Tripathi, Email: shloksk@gmail.com.

Papiya M Mazumder, Email: papiyamm@gmail.com.

Anil V Chandewar, Email: avchandewar@rediffmail.com.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful P. Wadhwani College of Pharmacy, Yavatmal (MS), India and Birla Institute of technology, Mesra for providing the financial support for this work.

References

- Melmed S, Polonsky SK, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 12. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders; pp. 1371–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale J. India’s Diabetes Epidemic Cuts Down Millions Who Escape Poverty. Retrieved: Bloomberg; 2010. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McGill M, Felton AM. New global recommendations: a multidisciplinary approach to improving out comes in diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2007;1:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama J, Wang D, Kondo T, SaitoI, Takagi K, Takagi K. et al. Toxicity of diazinon and its metabolites increases in diabetic rats. Toxicol Lett. 2007;170:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Tang D, Yin X, Gao Y, Wei Y, Chen Y. Pharmacokinetic study of rutin in normal and diabetic nephropathy rats. Acta Acad Med Xuzhou. 2009;29:708–712. [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Duan H, Wei Y, Zhang D, Li B, Wu X. Comparison on the pharmacokinetic of metformin hydrochloride between normal and diabetic rats. Chin J Mod Appl Pharm. 2009;26:433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wu K. Pharmacokinetics comparison of berberine in gengenqinlian detection between normal rats and diabetic rats. China Pharm. 2010;13:467–468. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons RL. Drug absorption in gastrointestinal disease with particular reference to mal absorption syndromes. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1977;2:45–60. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197702010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki MT, Aleksunes LM, Sawant SP, Dnyanmote AV, Mehendale HM, Manautou JE. Renal and hepatic transporter expression in type2 diabetic rats. Drug Metab Lett. 2008;2:11–17. doi: 10.2174/187231208783478425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimojo N, Ishizaki T, Imaoka S, Funae Y, Fujii S, Okuda K. Changes in amounts of cytochrome P450 isozyme sand levels of catalytic activities in hepatic and renal microsomes of rats with streptozocin- induced diabetes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:621–627. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90547-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Frassetto L, Benet LZ. Effects of renal failure on drug transport and metabolism. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier G, Riveline JP, Varroud VM. Management of drugs affecting blood glucose in diabetic patients with renal failure. Diabetes Metab. 2000;26:73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoyan X, Bin M. Cellular and humonal immune responses in the early stage of diabetic nephropathy. J Autoimmnity. 2009;32:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saisho K. et al. Extraction and determination of sildenafil (Viagra) and its N-desmethyl metabolite in rat and human hair by GC-MS. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:1384–1388. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno Y, Iyoda M, Shibata T, Hirai Y, Akizawa T. Sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor, attenuates diabetic nephropathy in non-insulin-dependent Otsuka Long- Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162(6):1389–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi AS, Sheikh I, Dewani AP, Shelke PG, Bakal RL, Chandewar AV, Mazumder PM. Development and validation of RP-HPLC method for sildenafil citrate in rat plasma-application to pharmacokinetic studies. Saudi Pharm J. 2012;21:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson KC, Gardiner SM, Hebden RA, Bennett T. Functional consequences of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus, with particular reference to the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44:103–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauer SM, Steffes MW, Ellis EN, Sutherland DE, Brown DM, Goetz FC. Structural-functional relationships in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1143–1155. doi: 10.1172/JCI111523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonia P, Rigatti F, Montorsi P. Sildenafil in erectile dysfunction: a critical review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:241. doi: 10.1185/030079903125001839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langtry HD, Markham A. Sildenafil: a review of its Use in erectile dysfunction. Drugs. 1999;57:967. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957060-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croom KF, Curran MP. Sildenafil: a review of its Use in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drugs. 2008;68:383. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotella DP. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors: current status and potential applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:674. doi: 10.1038/nrd893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montani D, Chaumais MC, Savale S, Natali D, Price LC, Jais X, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Sitbon O. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in pulmonary arterial hypertension Adv. Ther. 2009;26:813. doi: 10.1007/s12325-009-0064-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meibohm B, Mehrotra N, Gupta M, Kovar A. The role of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:253. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MP, Ziyadeh FN, Chen S. Amadori-modified glycated serum proteins and accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetes: pathogenic and therapeutic implications. J Lab Clin Med. 2006 May;147(5):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JF, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Nonenzymatically glucosylated albumin: in vitro preparation and isolation from normal human serum. J Biol Chem. 1979 Feb 10;254(3):595–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Cabello F, Erill S. Abnormal serum protein binding of acidic drugs in diabetes mellitus. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984 Nov;36(5):691–695. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worner W, Preissner A, Rietbrock N. Drug-protein binding kinetics in patients with type I diabetes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43(1):97–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02280763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns GL, Kemp SF, Turley CP. et al. Protein binding of phenytoin and lidocaine in pediatric patients with type I diabetes mellitus. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1988;11(1):14–23. doi: 10.1159/000457659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp SF, Kearns GL, Turley CP. Alteration of phenytoin binding by glycosylation of albumin in IDDM. Diabetes. 1987 Apr;36(4):505–509. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovik TS, Jaeger R, Jorde R. et al. Plasma protein binding of catecholamines, prazosin and propranolol in diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43(3):265–268. doi: 10.1007/BF02333020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovik TS, Jaeger R, Jorde R. et al. Reduced sensitivity to beta-adrenoceptor stimulation and blockade in insulin dependent diabetic patients with hypoglycaemia unawareness. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994 Nov;38(5):427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidenberg MM, Drayer DE. Alteration of drug-protein binding in renal disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1984 Jan;9(Suppl. 1):18–26. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198400091-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller F, Maiga M, Neumayer HH. et al. Pharmacokinetic effects of altered plasma protein binding of drugs in renal disease. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1984;9(3):275–282. doi: 10.1007/BF03189651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti G, Crema F, Attardo-Parrinello G. et al. Serum protein binding of phenytoin and valproic acid in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ther Drug Monit. 1987 Dec;9(4):389–391. doi: 10.1097/00007691-198712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara PJ, Blouin RA, Brazzell RK. The protein binding of phenytoin, propranolol, diazepam, and AL01576 (an aldose reductase inhibitor) in human and rat diabetic serum. Pharm Res. 1988 May;5(5):261–265. doi: 10.1023/A:1015966402084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zini R, Riant P, Barre J. et al. Disease-induced variations in plasma protein levels. Implications for drug dosage regimens (part II) Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990 Sep;19(3):218–229. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199019030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zini R, Riant P, Barre J. et al. Disease-induced variations in plasma protein levels: implications for drug dosage regimens (part I) Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990 Aug;19(2):147–159. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199019020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe N, Hashizume N. Drug binding properties of glycosylated human serum albumin as measured by fluorescence and circular dichroism. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994 Jan;17(1):16–21. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwilt PR, Nahhas RR, Tracewell WG. The effects of diabetes mellitus on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in humans. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1991 Jun;20(6):477–490. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199120060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. Diabetic nephropathy. Medicine. 2010;12(38):639–643. [Google Scholar]