Abstract

Chemotherapy is the most common treatment for cancer. However, multidrug resistance (MDR) remains a major obstacle to effective chemotherapy, limiting the efficacy of both conventional chemotherapeutic and novel biologic agents. The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), a xenosensor, is a key regulator of MDR. It functions in xenobiotic detoxification by regulating the expression of phase I drug metabolizing enzymes and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, whose overexpression in cancers and whose role in drug resistance make them potential therapeutic targets for reducing MDR. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous negative regulators of gene expression and have been implicated in most cellular processes, including drug resistance. Here we report the inversely related expression of miR-137 and CAR in parental and doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells, wherein miR-137 is down-regulated in resistant cells. miR-137 over-expression resulted in down-regulation of CAR protein and mRNA (via mRNA degradation); it sensitized doxorubicin-resistant cells to doxorubicin (as shown by reduced proliferation, increased apoptosis, and increased G2-phase cell cycle arrest) and reduced the in vivo growth rate of neuroblastoma xenografts. We observed similar results in cellular models of hepatocellular and colon cancers, indicating that the doxorubicin-sensitizing effect of miR-137 is not tumor type-specific. Finally, we show for the first time a negative feedback loop whereby miR-137 down-regulates CAR expression and CAR down-regulates miR-137 expression. Hypermethylation of the miR-137 promoter and negative regulation of miR-137 by CAR contribute in part to reduced miR-137 expression and increased CAR and MDR1 expression in doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells. These findings demonstrate that miR-137 is a crucial regulator of cancer response to doxorubicin treatment, and they identify miR-137 as a highly promising target to reduce CAR-driven doxorubicin resistance.

Keywords: microRNA, constitutive androstane receptor, miR-137, MDR1, doxorubicin

INTRODUCTION

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is the leading cause of cancer treatment failure. Members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family mediate cellular efflux to protect tissues from xenobiotics. The xenobiotic receptors, constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and pregnane X receptor (PXR) regulate the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters that contribute to drug resistance. 1 Because of the constitutive activity of CAR, 2 therapies that modulate CAR expression may effectively deter CAR-driven drug resistance.

Drug resistance is regulated in part by microRNAs (miRNAs), 3 which cause direct mRNA cleavage or translational repression via sequence-specific base pairing with the 3′ UTRs of target mRNA. 4 miRNAs regulate many biological processes,5, 6 affect cancer prognosis, 7 and may influence response to chemotherapy. 8, 9 The differential expression of miRNAs in drug-sensitive versus drug-resistant cells 10–13 suggests that modulation of miRNA expression may reduce or reverse drug resistance.

Neuroblastoma causes 15% of all childhood cancer-associated mortality. 14 It initially responds well to chemotherapy but frequently recurs in a chemoresistant form. Evidence suggests that chemoresistance increases with increased drug efflux mediated by up-regulation of ABC transporters, including MDR1, 15–17 and epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes through DNA hypermethylation. 18, 19 Identification of additional biomarkers independently associated with survival, and elucidation of their function, may offer greater insight into the underlying biology of the disease and the mechanisms of treatment response and relapse. Although miRNAs have not been extensively implicated in drug resistance in neuroblastoma, several studies have identified miRNAs associated with poor clinical outcome. 20–23

We investigated the functional relation of miRNAs to CAR, MDR1 (P-glycoprotein), and chemoresistance. miR-137, one of the few miRNAs predicted to target CAR, was selected for study because 1) it is broadly conserved in vertebrates, 2) it is reportedly hypermethylated in cancers, and 3) its absence in cancers is associated with reduced survival. 24–28 CAR expression was greater and miR-137 expression was less in doxorubicin-resistant versus -sensitive neuroblastoma cells. Further, miR-137 targeted the 3’UTR of CAR and negatively regulated CAR expression in neuroblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colon adenocarcinoma cells, identifying CAR as a bona fide target of miR-137. Restoration of miR-137 sensitized doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells and significantly reduced the growth of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts in vivo. Unexpectedly, CAR negatively regulated miR-137 expression and, together with hypermethylation of the miR-137 promoter, reduced miR-137 expression in doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma. These findings warrant further investigation of the clinical potential of reducing MDR by manipulating miRNA regulation of CAR.

RESULTS

Inverse relation of miR-137 and CAR levels in neuroblastoma cells

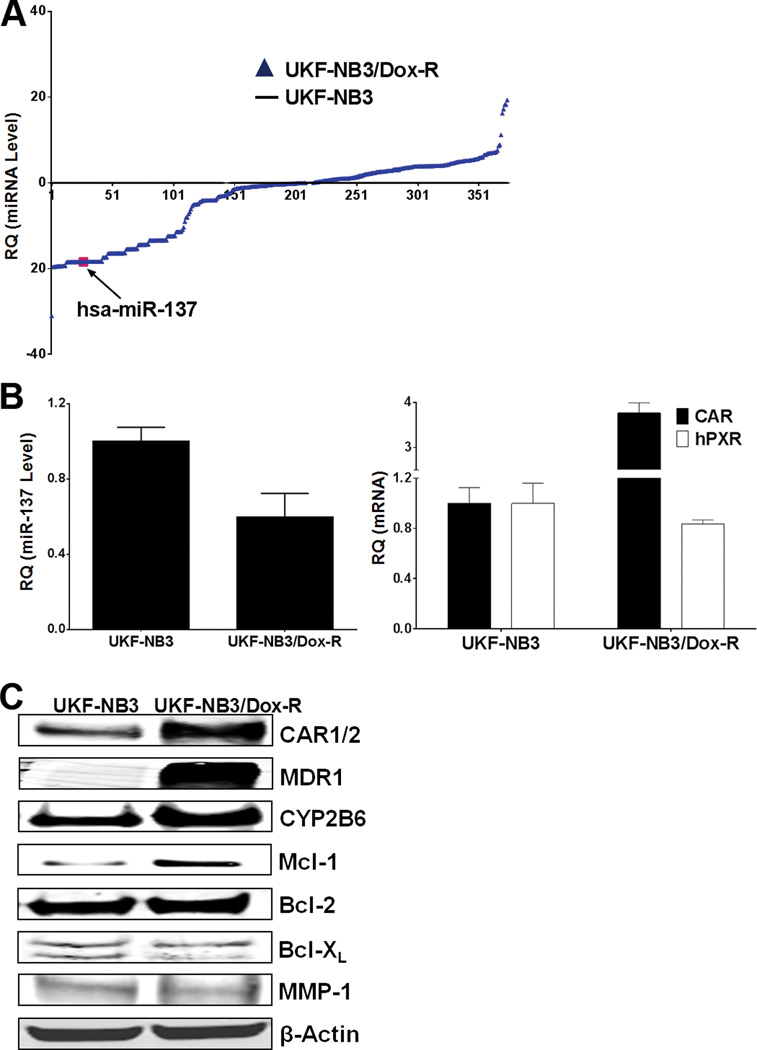

Recent studies have linked cancer drug resistance to altered expression of miRNAs.11 To investigate the change in miRNA expression in drug-resistant cancer cells, we used the parental (UKF-NB3) neuroblastoma cell line, isolated from bone marrow metastases from N-myc-amplified stage 4 neuroblastoma patients, and its doxorubicin-resistant sub-line, UKF-NB3rDox20 (UKF-NB3/Dox-R) generated by adapting the cells to grow in the presence of doxorubicin (20 ng/ml) as described, 29, 30 as experimental models. In UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells, miR-137 was among the miRNAs dramatically down-regulated, whereas CAR mRNA was up-regulated with little change in PXR mRNA (Figure 1A & 1B). Western blot analysis indicated greater expression of CAR and of its transcriptional target genes, MDR1, 31 CYP2B6, 32 and to a lesser extent, MCL1, 33 in resistant cells than in parental cells (Figure 1C). Mcl-1 participates in CAR-mediated anti-apoptotic effects and contributes to doxorubicin resistance. 34–36 In contrast, levels of doxorubicin-regulated Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, and MMP-1 37–39 were not found to differ significantly (Figure 1C). To determine whether the observed inversely related expression was cell type–specific, we measured CAR mRNA and miR-137 in parental and doxorubicin-resistant hepatocellular HepG2 and colon LS174 cancer cells by qRT-PCR. In doxorubicin-resistant cells, expression of miR-137 was lower and that of CAR mRNA was higher than in parental cells (Supplementary Figure 1A, B & C). However, HepG2 and LS174 cells expressed significantly greater CAR mRNA and lower miR-137 than UKF-NB3 cells (Supplementary Figure 1B & C). Taken together, these data suggest that prolonged doxorubicin treatment down-regulated miR-137, leading to up-regulation of CAR and its target gene MDR1, and contributed to doxorubicin resistance.

Figure 1.

Reciprocal expression of miR-137 and CAR in parental and doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma. (A) miR-137 expression is down-regulated in doxorubicin-resistant cells. The Megaplex Pools for microRNA Expression Analysis (Applied Biosystems Inc) were used for microRNA arrays. miRNA levels are expressed in log scale. (B) miR-137 expression is lower and CAR mRNA expression is higher in UKF-NB3/Dox-R than in UKF-NB3 cells. QRT-PCR was used to measure levels of miR-137 (left) and CAR mRNA (right). (C) Levels of CAR, MDR1, and CYP2B6 are higher in UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells than in UKF-NB3 cells, while levels of doxorubicin-regulated Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, and MMP-1 are similar. β-actin was used as loading control for Western blots. In experiments shown in (A) and (B), the miR-137 or CAR level was set to 1 in UKF-NB3 cells.

miR-137 as a negative regulator of CAR

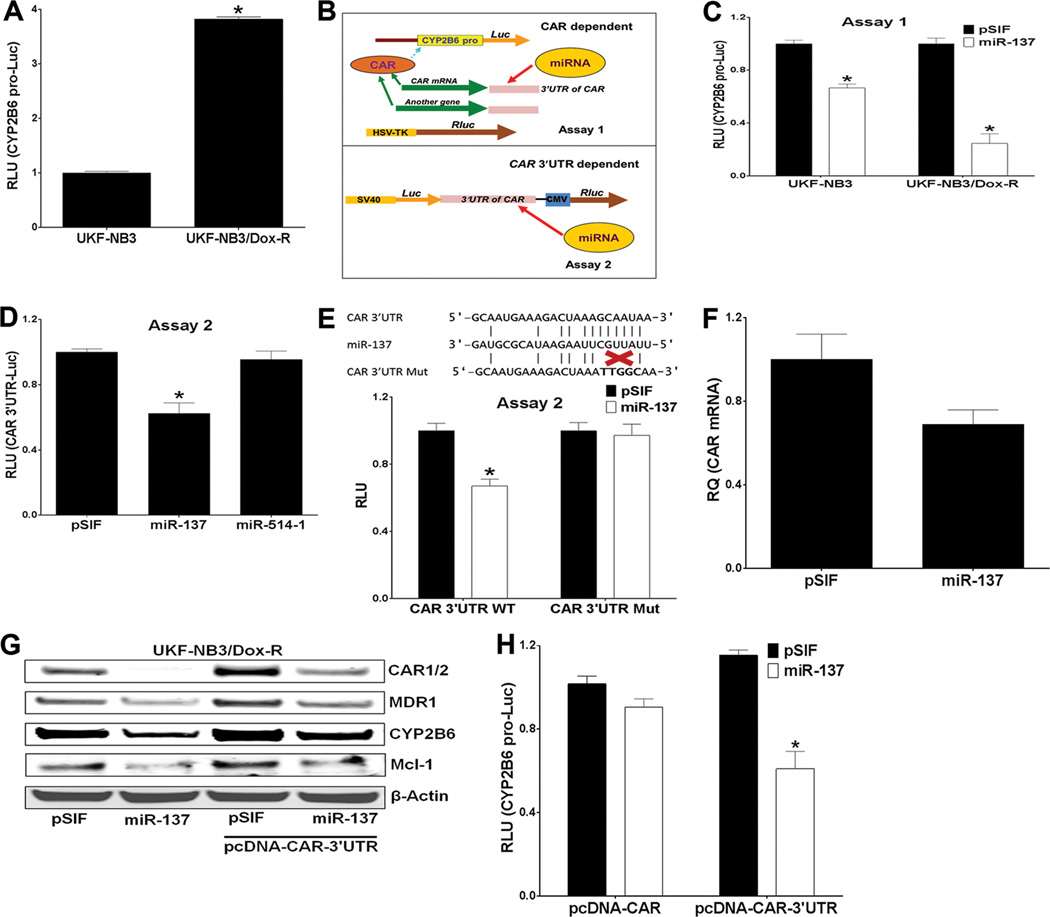

To determine whether elevated CAR levels in doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells increase the transcriptional activity of CAR, we performed a reporter luciferase assay in UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells co-transfected with the CAR-regulated CYP2B6 promoter reporter (CYP2B6pro-Luc) 32, 40 and a Renilla luciferase (Rluc) construct (as transfection control) for 48 h. As expected, CYP2B6pro-Luc activity was significantly greater in the doxorubicin-resistant cells than in the parental cells (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

miR-137 negatively regulates CAR by directly targeting its 3'UTR. (A) CYP2B6pro-Luc activity is higher in UKF-NB3/Dox-R than in UKF-NB3 cells. Luciferase assay was performed 48 h after transfection. The y-axis denotes the relative luciferase units (RLU) of CYP2B6pro-Luc (normalized to the co-transfected Renilla luciferase reporter, Rluc). RLU in UKF-NB3/Dox-R was compared to that in UKF-NB3 cells (set to 1) in the Student’s t test. (B) Outline of Assays 1 (to determine whether miR-137 represses CAR) and 2 (to determine whether miR-137 directly targets the CAR 3'UTR. (C) In Assay 1, miR-137 down-regulates CYP2B6pro-Luc. pSIF control expressed scrambled sequence. A Dual-Glo luciferase assay was performed 48 h after transfection. The y-axis denotes RLU of CYP2B6pro-Luc (normalized to Rluc). (D) In Assay 2, miR-137, but not miR-514-1 (a nonspecific control), down-regulates pEXZ-CAR 3'UTR-luc (the CAR 3'UTR is placed directly downstream of the luciferase gene) in 293T cells in a Dual-Glo luciferase assay 48 h after transfection. The y-axis denotes RLU of CAR 3’UTR-Luc (normalized to Rluc). (E) Modulation of Luc expression by miR-137 is abolished by a mutant CAR 3'UTR. A schematic representation of complementary binding of miR-137 to the CAR 3'UTR and CAR3'UTRmut (in which the miR-137 binding site is mutated) is shown above the bar graph depicting reporter activity from cells transfected with pSIF or miR-137 plus either WT 3'UTR or 3'UTRmut. (F) CAR mRNA is reduced by miR-137 overexpression. HepG2 cell were transfected with pSIF or miR-137 and mRNA level was assessed by qRT-PCR. (G) Immunoblotting shows that expression of endogenous and exogenous CAR and its transcriptional targets MDR-1, CYP2B6 and Mcl-1 is reduced by overexpression of miR-137 in UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells. β-actin was used as loading control. (H) miR-137 down-regulates pcDNA-CAR-3’UTR but not pcDNA-CAR. HepG2 cells were co-transfected with plasmids as indicated. * Indicates p ≤ 0.05. In the Student’s t test, RLU from miR-137 or miR-514-1 was compared to that from pSIF transfected cells (set to 1) in experiments shown in (C), (D), (E), and (H).

To determine whether miR-137 directly targets the CAR 3’UTR, we used reporter assays outlined in Figure 2B. 41 In Assay 1 over-expression of miR-137 significantly down-regulated reporter activity of CYP2B6 pro-Luc (Figure 2C). In Assay 2 we used pEXZ-CAR 3′UTR-luc, which contains the CAR 3′UTR cloned directly downstream of the luciferase gene, and Rluc under the control of a CMV promoter as transfection control. The pEXZ-CAR 3′UTR-luc construct was co-expressed with pSIF, miR-137 (predicted to target CAR), or miR-514-1 (not predicted to target CAR). miR-137, but not miR-514-1, down-regulated the activity of pEXZ-CAR 3′UTR-luc (Figure 2D). When mutations that disrupt the binding of CAR 3′UTR to the miR-137 “seed” sequence were introduced into pEXZ-CAR 3′UTR-luc (to generate CAR 3′UTR Mut), the down-regulation of luc by miR-137 was abolished (Figure 2E), indicating that CAR is a bona fide miR-137 target gene. Steady-state CAR mRNA levels were significantly reduced when miR-137 was overexpressed (Figure 2F), indicating that mRNA degradation likely contributed to miR-137–mediated CAR suppression. As expected, overexpression of miR-137 reduced CAR (both endogenous and exogenously expressed from the pcDNA-CAR 3'UTR), CYP2B6, MDR1, and Mcl-1 proteins (Figure 2G). Furthermore, miR-137 negatively regulated CYP2B6 pro-Luc when co-expressed with a pcDNA-CAR-3’UTR construct but not when co-expressed with pcDNA-CAR (lacking the 3'UTR) (Figure 2H), further demonstrating that miR-137 regulation of CAR is CAR-3’UTR–dependent. Collectively, these data indicate that miR-137 is a bona fide negative regulator of CAR.

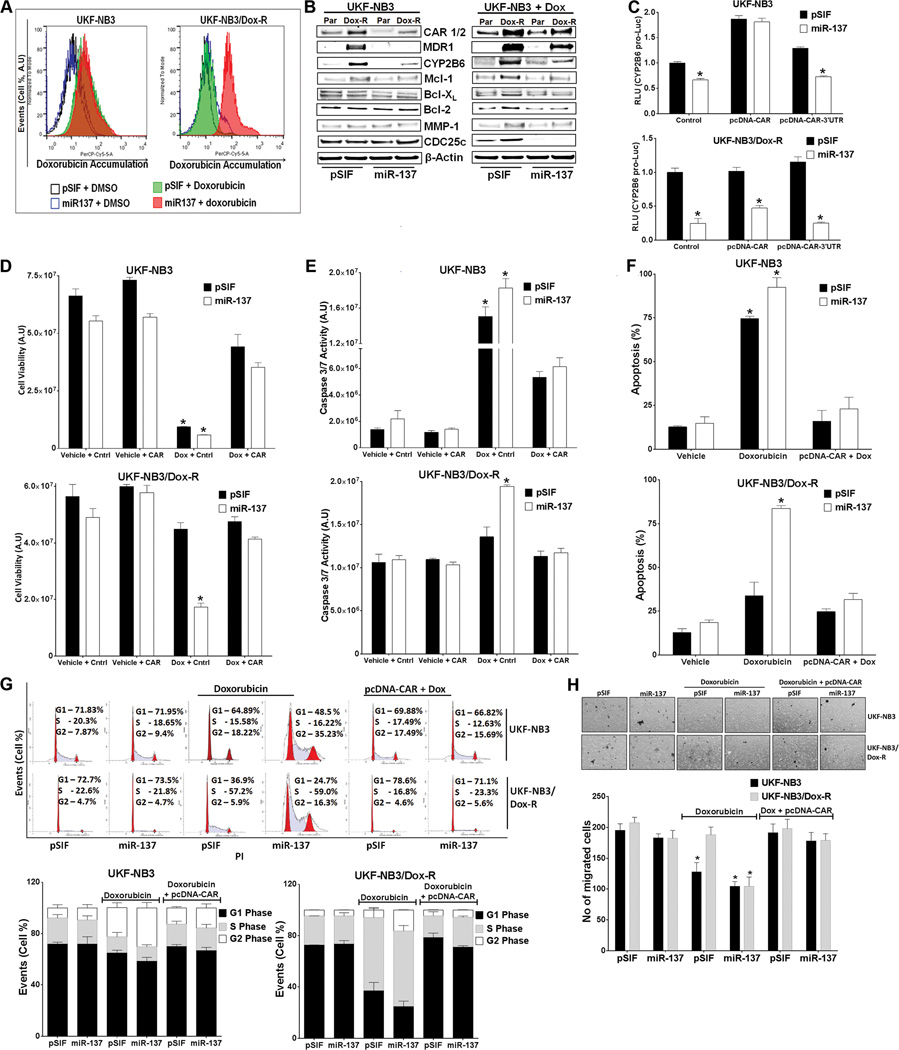

miR-137 down-regulates CAR expression and re-sensitizes doxorubicin-resistant cells to doxorubicin

Tumor-suppressive miRNAs generally target oncogenes or repress cell growth–promoting factors. miR-137 is viewed as a tumor suppressor down-regulated in cancers. 24, 42, 43 Doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells expressed a lower level of miR-137 and a higher level of CAR and MDR1 than did parental cells (Figure 1). Doxorubicin is a substrate of MDR1.44, 45 To test the hypothesis that increased miR-137 reduces levels of CAR to increase intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin and drug sensitivity, we ectopically expressed miR-137 stably in parental and doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells. Ectopically expressed miR-137, but not vector control, caused intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin in UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells (Figure 3A). Over-expression of miR-137 down-regulated CAR, CYP2B6, MDR1, and Mcl-1 protein levels in both cell lines (Figure 3B). Consistent with the intracellular accumulation caused by ectopically expressed miR-137, doxorubicin treatment resulted in down-regulation of doxorubicin-regulated Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, MMP1, and CDC25c in doxorubicin-resistant cells when miR-137 was overexpressed (Figure 3B, right panel). These data suggest that overexpression of miR-137 decreases CAR and MDR1 to increase intracellular doxorubicin levels. miR-137-mediated down-regulation of CAR reduced CAR transcriptional activity, which was rescued by pcDNA-CAR but not by pcDNA-CAR-3’UTR (Figure 3C). In UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells, pcDNA-CAR only modestly rescued the effect of miR-137 (Figure 3C) (it is likely that the high level of endogenous CAR masked the effect of exogenously expressed CAR).

Figure 3.

miR-137 down-regulates CAR expression and function and sensitizes doxorubicin-resistant cells to doxorubicin. (A) miR-137 increases intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin in UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells. UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells stably expressing pSIF or miR-137 were treated with vehicle or 0.5 µM doxorubicin for 6 h, and intracellular doxorubicin was measured by flow cytometry. The y-axis denotes events (no. of cells) and the x-axis denotes emitted fluorescence (the level of doxorubicin). (B) Immunoblotting shows that miR-137 overexpression reduces protein levels of CAR and its transcriptional targets MDR-1, CYP2B6, and Mcl-1 (as compared to that in pSIF control cells) in UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells. Doxorubicin-regulated Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, CDc25c and MMP-1 are reduced in UKF-NB2/Dox-R cells treated with 0.1 µM doxorubicin only when miR-137 was overexpressed. β-actin was used as loading control. (C) Down-regulation of CYP2B6pro-Luc by miR-137 is rescued by pcDNA-CAR. Cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids or control (pcDNA3.1+). RLU from miR-137 was compared to that from pSIF-transfected cells in the Student’s t test. (D-H) miR-137 re-sensitizes UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells, an effect rescued by pcDNA-CAR. Cell Titer Glo cell proliferation (72 h treatment) (D), caspase 3/7 activity (24 h treatment) (E), Annexin V apoptosis (24 h treatment) (F), cell cycle analysis (24 h treatment) (G), and cell migration (H) assays were performed with and without transfection with pcDNA3.1+ (Cntrl) or pcDNA-CAR (CAR) and with vehicle or 0.5 µM doxorubicin (Dox) treatment. (G) Top: representative data from a single experiment. The y-axis denotes events (no. of cells) and the x-axis denotes emitted fluorescence. Bottom: bar graphs summarize data from three independent experiments. (H) Top: representative images of cell migration. Bottom: bar graphs summarize data from three independent experiments. * Indicates p ≤ 0.05. In the Student’s t test, samples were compared to the control sample (cells transfected with pSIF, Cntrl and treated with vehicle) in experiments shown in (D), (E), (F), and (H).

Doxorubicin reduces Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL to reduce cell proliferation and increase apoptosis 39, 46; inhibits MMP-1 to reduce cell migration 37; and down-regulates CDC25c to arrest cell cycle progression. 47, 48 Consistent with the intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin (Figure 3A) and expression levels of doxorubicin-regulated genes (Figure 3B), miR-137 re-sensitized doxorubicin-resistant cells to doxorubicin treatment, as indicated by decreased cell viability (Figure 3D), increased activation of caspase 3/7, apoptosis, and G2 cell cycle arrest (Figure 3E–G), and reduced cell migration (Figure 3H), all of which were rescued by ectopically expressed CAR (pcDNA-CAR lacking the 3’UTR). Similar results were observed in doxorubicin-resistant HepG2 and LS174T cells (Supplementary Figure 2; cell migration assay not performed), indicating that the effect of miR-137 on doxorubicin resistance is not tumor type–specific and that miR-137 may reverse CAR-driven drug resistance in tumor cells by increasing intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin.

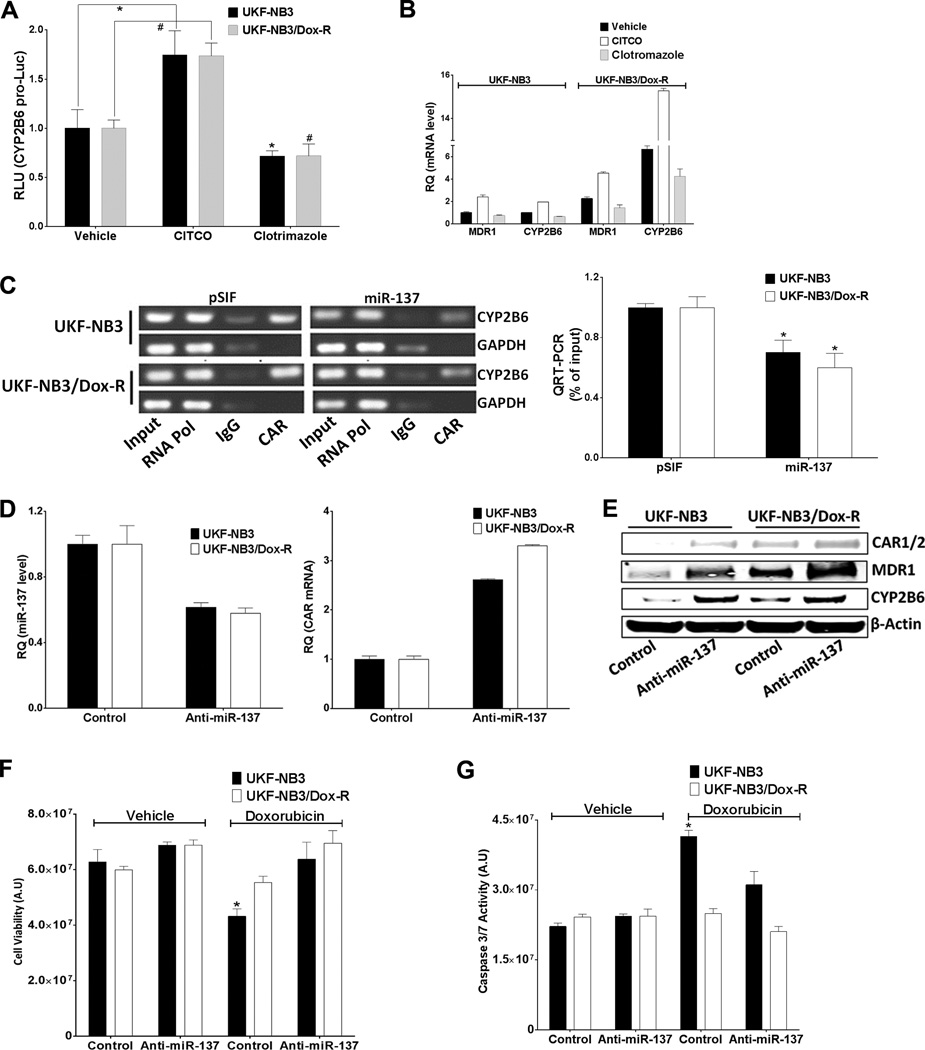

To further confirm that the overexpressed CAR was functional and could be modulated, we showed that the CAR inverse agonist clotrimazole decreased, while the CAR agonist CITCO increased, CYP2B6 promoter activity (Figure 4A) and endogenous MDR1 and CYP2B6 mRNA levels (Figure 4B). In addition, in a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay, CAR bound to CYP2B6 promoter, and this binding was decreased when miR-137 was ectopically expressed (Figure 4C). IgG and anti-RNA polymerase II were used as non-specific negative and positive controls, respectively, in the ChIP assay. To further confirm the inverse relation between miR-137 level and CAR, we used anti-miR-137 (antisense oligonucleotides harboring complementary reverse sequences of miR-137 expressed from a plasmid) to reduce the level of endogenous miR-137, which increased the level of CAR mRNA (Figure 4D) and CAR, MDR1, and CYP2B6 protein (Figure 4E) in doxorubicin-sensitive neuroblastoma cells (which possess higher levels of endogenous miR-137). Anti-miR-137 also reduced the doxorubicin sensitivity of UKF-NB3 cells, as measured by cell viability and caspase 3/7 activation (Figure 4F & G). CITCO, clotrimazole, and anti-miR-137 produced similar effects in colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (Supplementary Figure 3). Collectively, our findings showed that the overexpressed CAR in doxorubicin-resistant cells is functional and that increasing levels of miR-137 reduce CAR and MDR1 levels, increase intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin and re-sensitize the doxorubicin-resistant cells.

Figure 4.

CAR is functional in UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells. (A) CYP2B6 promoter is activated by CITCO but inhibited by clotrimazole. Cells were transfected with CYP2B6pro-Luc and RLuc 24 h before treatment with vehicle, 100 nM CITCO, or 1 µM clotrimazole for 48 h, followed by Dual-Glo luciferase assay. In the Student’s t test, RLU from CITCO or clotrimazole was compared to that from vehicle (* for UKF-NB3 and # for UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells). (B) MDR1 and CYP2B6 are induced by CITCO but reduced by clotrimazole (48 h treatment). qRT-PCR was used to measure expression of MDR1 and CYP2B6 mRNA. (C) CAR binds to the CYP2B6 promoter, but binding is reduced by miR-137 in a ChIP assay. Right: bar graphs show fold change in relative binding. Input shows 10% of sample used; IgG and anti-RNA Pol II were used as non-specific negative and positive controls, respectively. In the Student’s t test, activity from miR-137 was compared to that from pSIF for each cell line. (D-G) Anti-MiR-137, but not control vector (Control), inhibits miR-137, thereby reducing miR-137 (D), inducing CAR (D and E), MDR1, and CYP2B6 (E), and significantly reducing the doxorubicin sensitivity of UKF-NB3 cells, as shown by cell viability (F) and caspase 3/7 activation (G) assays. * and # Indicate p ≤ 0.05. In the Student’s t test in experiments shown in (F) and (G), samples were compared to the control (cells transfected with control vector and treated with vehicle).

CAR and miR-137 form a negative feedback loop and hypermethylation of the miR-137 promoter contributes to reduced miR-137 expression in doxorubicin-resistant cells

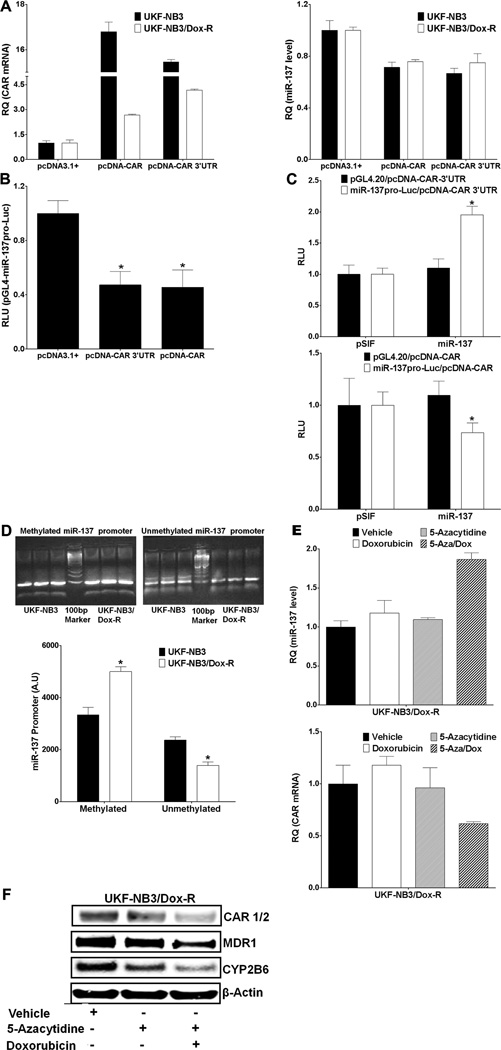

CAR is involved in both transcriptional activation and transcriptional repression.49 To determine whether CAR contributes to reduced miR-137 expression in UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells, we performed qRT-PCR after overexpression of CAR. Exogenously expressed CAR led to reduced miR-137 expression (Figure 5A). Of the two putative promoters that might regulate expression of miR-137, the distal promoter should also regulate miR-2682. Overexpression of CAR did not affect expression of miR-2682 (Supplementary Figure 4), suggesting that CAR represses miR-137 expression at the proximal promoter. For confirmation, we cloned the miR-137 promoter into the pGL4.20 vector directly upstream of the luciferase gene (miR-137pro-Luc) and co-expressed this construct with pcDNA-CAR plasmid. We found significantly less miR-137pro-Luc activity in cells expressing CAR than in those expressing pcDNA3.1+ (Figure 5B). To determine whether CAR repression of the miR-137 promoter is compromised by ectopically expressed miR-137, we examined the activity of miR-137pro-Luc in HepG2 cells co-transfected with pSIF or miR-137 and pcDNA-CAR or pcDNA-CAR 3'UTR. miR-137pro-Luc activity increased in cells co-transfected with miR-137 and pcDNA-CAR 3’UTR but not in cells co-expressing miR-137 and pcDNA-CAR (construct lacking the 3'UTR) (Figure 5C). These results indicated an unusual negative feedback loop between miR-137 and CAR.

Figure 5.

Methylation of the miR-137 promoter and expression of CAR reduce miR-137 expression in doxorubicin-resistant cells. (A) qRT-PCR shows that exogenous CAR overexpression (left) reduces miR-137 expression (right) in UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells. (B) Luciferase activity of a miR-137 promoter cloned directly upstream of the luciferase gene in the pGL4.20 vector (pGL4-miR137pro-Luc) is reduced by co-transfection with pcDNA-CAR or pcDNA-CAR3’UTR in HepG2 cells (compared to pcDNA3.1+ control in the Student’s t test). (C) pcDNA-CAR3’UTR inhibition of miR-137 promoter (miR137pro-Luc) activity (top), but not of pcDNA-CAR (bottom), is rescued by miR-137 overexpression (activity from miR-137 was compared to that from pSIF in the Student’s t test). (D) Methylation-specific PCR shows greater methylation of the miRNA-137 promoter in doxorubicin-resistant than in doxorubicin-sensitive neuroblastoma cells. Primers for fully methylated and fully demethylated alleles of the promoter were used to amplify bisulfite-converted genomic DNA. Top: a representative gel. Band intensity was quantified by using ImageJ software. Bottom: values on bar graph represent the mean and SD of three samples. AU (arbitrary unit) from UKF-NB3/Dox-R was compared to that from UKF-NB3 cells in the Student’s t test. (E and F) UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells were treated for 72 h with 2.5 µM 5-azacytidine (Sigma), alone or together with 0.5 µM doxorubicin. Drug and medium were replaced every 24 h, followed by qRT-PCR (E) and Western blot analysis (F). * Indicates p ≤ 0.05.

Several studies have shown down-regulation of miR-137 in various tumors,24, 42, 43 and hypermethylation at the miR-137 promoter contributes to the down-regulation. 24–26 We performed methylation-specific PCR of the miR-137 promoters and found that the promoters were more methylated in UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells than in UKF-NB3 cells (Figure 5D), suggesting that methylation contributes to the reduced miR-137 expression in these cells. In UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells cultured in doxorubicin, methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine (72 h treatment) increased miR-137 expression, reduced CAR mRNA (Figure 5E) and reduced protein levels of CAR, MDR, and CYP2B6 (Figure 5F).

Collectively, these data indicate a negative feedback loop between miR-137 and CAR, wherein CAR negatively regulates miR-137 expression and miR-137 negatively regulates CAR expression. Increased methylation of the miR-137 promoter also contributes to the lower miR-137 expression in doxorubicin-resistant cells. Therefore, miR-137 promoter hypermethylation and CAR overexpression contribute to down-regulation of miR-137 in doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells.

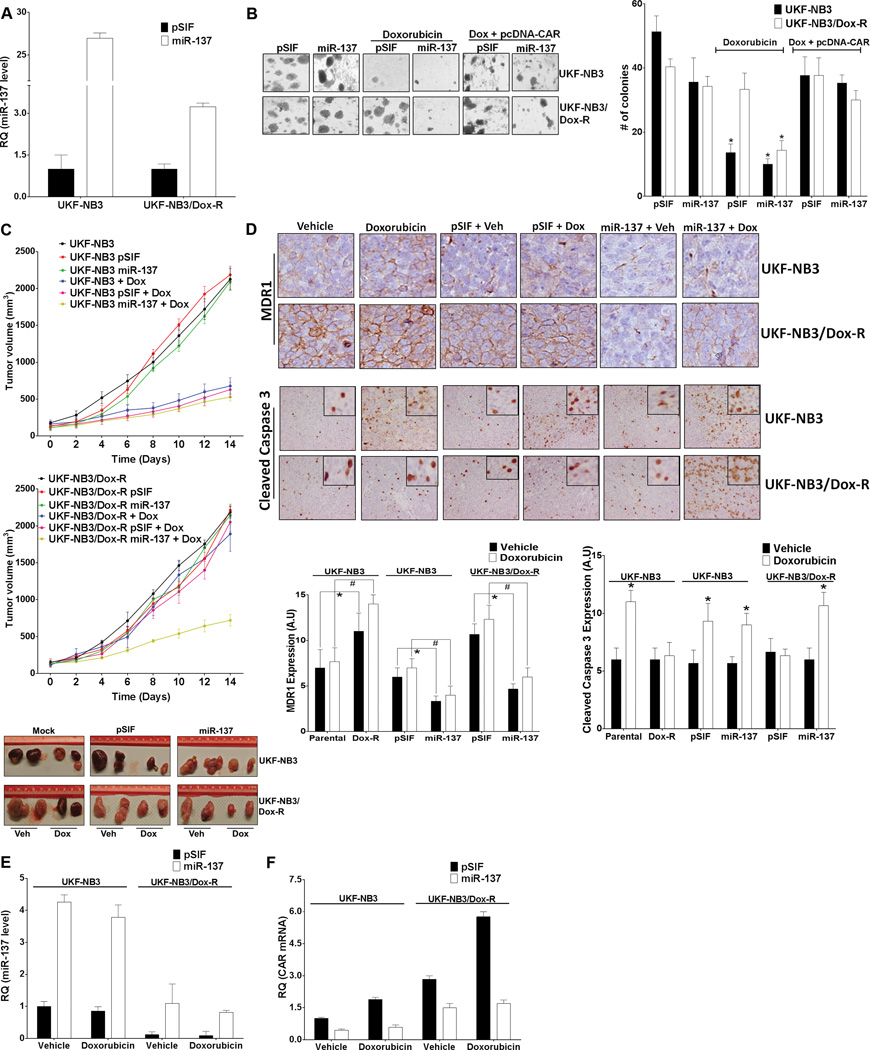

miR-137 reduces growth of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts

Soft-agar colony formation assays are routinely used to detect anchorage-independent growth (a hallmark of cell transformation). We used this assay to investigate whether miR-137 sensitization of doxorubicin-resistant cells was sufficient to reduce their transformation capability. UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells stably expressing pSIF or miR-137 (Figure 6A) were incubated in soft agar for 2 weeks, with vehicle or doxorubicin treatment every 72 h. Without doxorubicin, the two cell lines formed colonies of similar number and size, regardless of miR-137overexpression (Figure 6B). With doxorubicin treatment, pSIF- and miR-137–expressing doxorubicin-sensitive UKF-NB3 cells formed smaller and fewer colonies (smallest in miR-137–expressing cells). Significantly, miR-137–expressing UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells formed smaller and fewer colonies with doxorubicin treatment than did pSIF-expressing cells (Figure 6B). Exogenous overexpression of CAR rescued the reduced colony formation, indicating that this reduction was CAR-dependent (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of miR-137 reduces the growth of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts. (A) Levels of miR-137 indicated by qRT-PCR in neuroblastoma cells stably transduced with lentivirus containing pSIF or miR-137. (B) Stable expression of miR-137 sensitizes neuroblastoma cells to doxorubicin-mediated reduction of anchorage-independent colony formation. Left: representative image of colonies. Right: bar graphs summarizing data from 3 independent experiments. Number of colonies from doxorubicin-treated cells (“Doxorubicin” group, the 4 bars in the middle; and “Dox + pcDNA-CAR” group, the 4 bars on the right) was compared to that from corresponding vehicle-treated cells (the first 4 bars on the left) in the Student’s t test. (C) Growth of UKF-NB3 neuroblastoma xenografts is significantly reduced by doxorubicin (top), but growth of UKF-NB3/Dox-R xenografts is reduced only when cells express miR-137 (center). Top and center panels show tumor growth rate over time (days); bottom panel shows tumor volume (two xenografted tumors per treatment group were shown) after 2 weeks of doxorubicin treatment. (D) In UKF-NB3/Dox-R tumors, MDR1 is down-regulated by miR-137 but cleaved caspase 3 is up-regulated by doxorubicin only when miR-137 is overexpressed. Top: representative immunohistochemistry images showing MDR1 and cleaved caspase-3 levels. Bottom: values represent at least 3 independent immunohistochemistry assays. For the expression level of MDR1, samples as noted in brackets were compared in the Student’s t test. For the levels of cleaved caspase-3, doxorubicin-treated samples were compared with the vehicle-treated samples for each of the 6 cell lines. * and # indicate p ≤ 0.05. (E,F) qRT-PCR shows over-expression of miR-137 (E) and down-regulation of CAR mRNA (F) in xenografts generated from miR-137–expressing cells. Expression of miR-137 and CAR mRNA is normalized to expression in tumors generated from parental pSIF-expressing UKF-NB3 cells treated with vehicle.

We next used a subcutaneous xenograft model to determine whether miR-137 reduces the growth of doxorubicin-treated UKF-NB3/Dox-R tumors in vivo. The growth rate of the doxorubicin-sensitive tumor cells was reduced by doxorubicin irrespective of miR-137 expression (Figure 6C). In contrast, the growth rate of UKF-NB3/Dox-R xenografts was reduced by doxorubicin only when miR-137 was expressed (Figure 6C). MDR1 levels were reduced in all xenografts in which miR-137 was expressed, regardless of doxorubicin treatment (Figure 6D). In UKF-NB3 xenografts, doxorubicin treatment led to higher levels of cleaved caspase 3, irrespective of miR-137 expression. However, in UKF-NB3/Dox-R xenografts, doxorubicin treatment increased levels of cleaved caspase 3 only when miR-137 was expressed (Figure 6D). qRT-PCR confirmed the higher expression of miR-137 from miR-137-expressing tumors (Figure 6E and Supplementary Figure 5A) and the inversely related CAR mRNA levels (Figure 6F and Supplementary Figure 5B). Together, these results indicated that the miR-137 level is crucial to the response of neuroblastoma to doxorubicin.

DISCUSSION

Here we showed that expression of CAR and its target, MDR1, is higher in doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells than in their doxorubicin-sensitive parental cells, whereas PXR shows no change. This finding suggests that CAR, reported to be overexpressed in various other cancers, drives doxorubicin resistance via up-regulation of MDR1. We showed that negative regulators of CAR, such as miR-137, can reduce CAR-mediated drug resistance.

Evidence increasingly suggests that epigenetic changes play a crucial role in the development and progression of human malignancies.50 Altered expression of miRNAs, a common feature of malignancies,51, 52 has recently been linked to epigenetic mechanisms. 53 Methylation of the CpG island of miR-137 has been discovered in oral, 27 colon, 24, 25 and gastric 26 cancers, associated with poorer survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, 28 and detected in oral rinses from these patients, suggesting its utility as a cancer biomarker. 54 Balaguer et al. showed that miR-137 is epigenetically regulated in colorectal cancer and that reduced expression contributes to colorectal carcinogenesis. 24 miR-137 is considered to act as a tumor suppressor by targeting pro-survival genes such as those encoding CDK6, MITF, 42 CDC42,55 and ERRα.56 We showed that increased methylation of the miR-137 promoter contributes to reduced miR-137 expression in doxorubicin-resistant cells. Further, treatment of doxorubicin-resistant cells with the methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine resulted in up-regulation of miR-137 expression. We also found that CAR negatively regulates miR-137. Our findings demonstrate that CAR overexpression contributes to reduced miR-137 expression. Therefore, we have shown for the first time a negative feedback loop between CAR and miR-137, wherein each negatively regulates the other.

Down-regulation of CAR by miR-137 reduced expression of MDR1, suggesting that levels of miR-137 may affect intracellular drug levels. We found that intracellular doxorubicin levels were higher in miR-137–expressing than in pSIF-expressing cells, resulting in decreased expression of doxorubicin-regulated proteins (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, MMP-1, CDC25c) and increased sensitivity of doxorubicin-resistant cells to doxorubicin, as evidenced by increased G2 cell cycle arrest, caspase 3/7 activity, and apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation. Overexpression of miR-137 significantly increased the doxorubicin-mediated growth inhibition of xenografts in mice. The effect of miR-137 on doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma cells was not tumor-specific, as results were similar in doxorubicin-resistant colon cancer (LS174) and hepatocellular cancer (HepG2) cell lines.

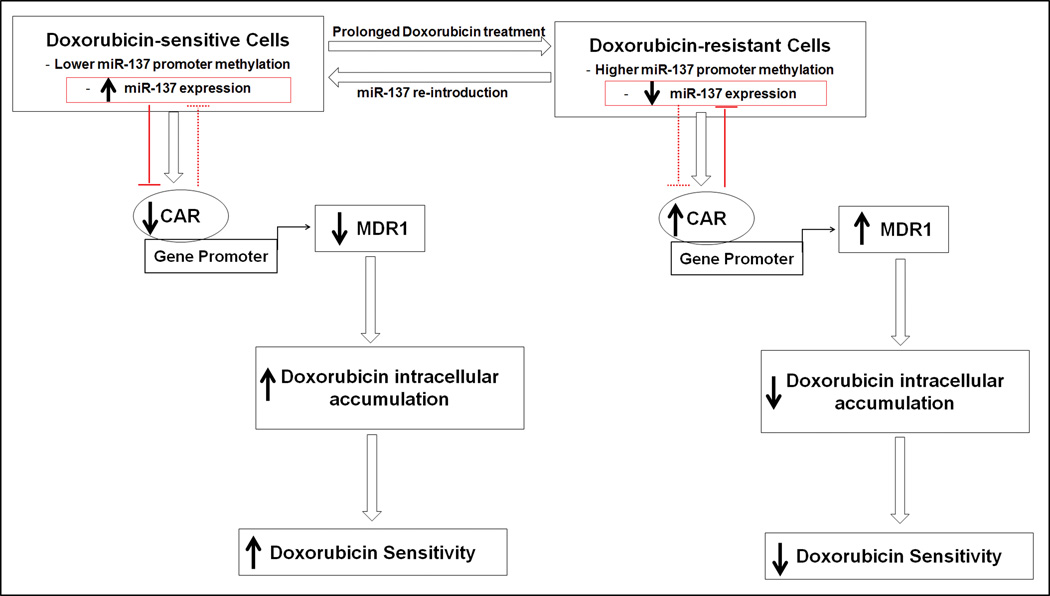

We observed lower expression of miR-137 and greater reciprocal expression of CAR and MDR1 in doxorubicin-resistant cells than in parental cells. Multiple studies have shown miR-137 to act as a tumor suppressor whose promoter is hypermethylated in cancer, 24–28 suggesting that miR-137 might play a role in carcinogenesis. We have demonstrated for the first time that epigenetic silencing of an miRNA (miR-137) in doxorubicin-resistant cells contributes to over-expression of CAR and, in turn, MDR1. miR-137, which negatively regulates CAR (and in turn MDR1 and CYP2B6), sensitized doxorubicin-resistant cells to doxorubicin. Down-regulation of MDR1 and CYP2B6 increased the intracellular doxorubicin levels, enhancing the therapeutic effect of doxorubicin. We also report for the first time a negative feedback loop between CAR and miR-137, in which one negatively regulates the expression of the other. Collectively, our results suggest a novel therapeutic possibility: incorporation of a miRNA into combination chemotherapy to reduce drug efflux in cancers that develop CAR-mediated drug resistance. Synthetic miRNAs (miR mimetics) can mimic the endogenous functions of an miRNA but have not yet demonstrated in vivo efficacy because of low stability and poor cellular delivery. 57–60 Alternative approaches to increase the expression of endogenous miRNA, including the use of small molecules, 41, 61 should be explored to further validate this therapeutic concept. Figure 7 summarizes the functional relationships of miR-137, CAR, MDR1, and cellular drug sensitivity revealed by our findings.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the functional inter-relationship of miR-137, CAR, MDR1, and cellular drug sensitivity. CAR negatively regulates miR-137; miR-137 negatively regulates CAR. Over-expression of CAR up-regulates MDR1 and reduces intracellular accumulation of and cellular sensitivity to doxorubicin. Solid arrows indicate high or low level or sensitivity. Open arrows indicate direction of events. Blunt arrows indicate negative regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transfection, and transduction

Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2. 293T, HepG2, and LS174 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured according to ATCC guidelines. UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R were cultured as previously described. 29, 62–64 The doxorubicin-resistant HepG2 and LS174 cells (HepG2/Dox-R, LS174/Dox-R) were generated by adapting the cells to doxorubicin (20 ng/ml) for 4–6 months in essential modified Eagle’s medium (EMEM, ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1% (v/v) antibiotic–antimycotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) or Fugene 6 (Promega; Madison, WI) was used for transient transfection. Dual luciferase assays were performed as previously described. 65 miRNAs were stably expressed by transduction with lentivirus carrying the MIR137 gene or the pSIF control vector. 41

Molecular cloning and assays

CAR 3’UTR was cloned by GeneCopoeia Inc. (Rockville, MD) directly downstream of a luciferase gene of the pEZX-MT01 vector, which also carries a Renilla luciferase (Rluc) gene controlled by a CMV promoter (transfection control). The pEZX-CAR 3’UTR mutant contains mutations at the binding site of the miR-137 “seed” region (5'…AGCAAUAA…3’ to 5'…AGTGGCGA…3’) (Mutagenex, Piscataway, NJ). We used the forward (5'-ATTCTAGAGGCCATGCTCACTTCC-3’) and reverse (5'-CTTTCTGATTTCGTTATTCGCCGGCGTA-3’) primers to PCR-amplify the CAR 3’UTR from pEZX-CAR 3’UTR and inserted it into pcDNA-CAR (containing the full human CAR coding sequence) directly downstream of the CAR gene to generate a pcDNA-CAR 3’UTR. The miR-137 promoter was PCR-amplified from HepG2 genomic DNA by using forward (5'-TCCGATCTGGAAGTTCCGCG-3’) and reverse (5'-GTAGCACTTTCTTGTTCTTTTC-3’) primers and cloned directly upstream of a luciferase gene in pGL4.20 (Promega) to generate the pGL4.20-miR-137pro-Luc. All miRNA constructs were obtained from an existing library, 41 and all DNA constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

The following primary antibodies were used in Western blot analyses: anti-CAR (sc-8540), anti-MDR1 (sc-55510), anti-CYP2B6 (sc-67224), anti-Mcl-1 (sc-12756), anti-Bcl-XL (sc-8392), anti-Bcl-2 (sc-509), anti-MMP-1 (sc-21731), anti-CDC25c (sc-55513) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); and anti-β-actin (AC-15) (Sigma). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-mouse, and donkey anti-goat IRDye 800WC or IRDye 680LT (LI-COR Biosciences; Lincoln, NE). An LI-COR Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR Biosciences) was used to detect protein bands.

MicroRNA array and quantitative real-time PCR

We used the Megaplex Pools for microRNA Expression Analysis (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA) to compare miRNA expression among cell lines. cDNA, generated by RT-PCR, was analyzed on an H7900-cycle 384-well TaqMan Low Density Array. Data were analyzed by using the Qiagen DataAssist software, arbitrarily assigning a value of 1.0 to expression levels in parental cells. We used TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems Inc.) to measure expression of mature miRNAs and CAR mRNA, using U6 RNA and β-actin mRNA as respective references. 66 Total RNA (0.1 µg) was generated from cells or xenograft samples by using the Maxwell 16LEV simplyRNA tissue kit (Promega).

Methylation-specific PCR

DNA was extracted from cells with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) and treated with sodium bisulfite using the Qiagen Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit. Methylated MIR137 promoter was amplified by methylation-specific PCR and separated on a 4% agarose gel. The primer sequences were: 5′-GCGGTAGTAGTAGCGGTAGC-3’ and 5′-ACCCGTCACCGAAAAAAA-3’ (for methylated alleles); 5′-GGTGGTAGTAGTAGTGGTAGT-3’ and 5′-TACCCATCACCAAAAAAAA-3’ (for unmethylated alleles) (expected amplicon, 86 bp each).54 Fully methylated and unmethylated bisulfite-converted human DNAs (Qiagen) were used as positive and negative controls. Band intensity was measured by using ImageJ software. Three samples were analyzed per cell line.

Doxorubicin intracellular uptake assay

UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells stably expressing pSIF- or miR-137 (1×106/well) were seeded into 6-well plates, incubated with DMSO or 0.5 µM doxorubicin for 6 hours at 37°C, washed ×2 with FACS buffer, and resuspended in FACS buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS). The intrinsic fluorescence of intracellular doxorubicin 67 was excited with an argon laser at 488 nm and emission was read in an LSR II Flow Cytometer (BD Bioscience), using a 620-nm filter.68, 69 Histograms were generated using FlowJo 10 software (Tree Star), and each included a minimum of 200,000 living cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells stably expressing pSIF- or miR-137 and plated in 10-mm dishes were cross-linked and processed as previously described. 70 Precleared chromatin solution was incubated overnight at 4°C with 5 µg of anti-hCAR (Perseus Proteomics), anti-RNA Pol II (positive control), or normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; negative control). Immunoprecipitates were collected and DNA was purified by using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The PBREM region of the CYP2B6 promoter was amplified by the SYBR green method, using the purified DNA as template and the primers CYP2B6-F: 5′-CTGCAATGAGCACCCAATCTT-3’ and CYP2B6-R: 5′-ACACATCCTCTGACAGGGTCA-3′ as previously described.71

Cellular assays

To determine whether miR-137 targets the 3’UTR of CAR, cells were co-transfected with pEZX-CAR 3'UTR (wild-type or mutated at the miR-137 “seed” binding region) and pSIF, miR-137, or miR-514-1 for 48 h in 96-well plates, and the Dual-Glo luciferase assay (Promega) was performed. Values were normalized to pSIF control. CAR transcriptional activity was determined similarly after co-transfection of cells with a CYP2B6 promoter-luciferase construct (CYP2B6pro-Luc), CMV-Rluc, pcDNA-CAR, or pcDNA-CAR 3’UTR and pSIF or miR-137 for 48 h. The effect of miR-137 on endogenous CAR activity was assessed in UKF-NB3 and UKF-NB3/Dox-R cells co-transfected for 48 h with CYP2B6pro-Luc, CMV-Rluc, and pSIF or miR-137. To determine whether CAR regulates the miR-137 promoter, cells were co-transfected for 48 h with pSIF or miR-137; pcDNA-CAR, or pcDNA-CAR 3'UTR; and pGL4.20 or pGL4.20-miR-137pro-Luc. Luminescence was read on an Envision Multilabel Plate Reader (Perkin Elmer; Waltham, MA).

Cell proliferation was assessed by using the Cell Titer Glo assay (Promega). Apoptosis was measured by using the Annexin V apoptosis assay (Miltenyi Biotec; Auburn, CA) in 6-well format and the Caspase Glo 3/7 kit (Promega) in a 96-well format. Cells were transfected in 96-well plates with pSIF or miR-137 with or without pcDNA-CAR and treated with vehicle or 0.5 µM doxorubicin for 72 h and 24 h, respectively, before the assays. Similar assays were performed after transfection of cells with an anti-sense miR-137 plasmid or a scrambled antisense control.

Cell migration was assayed in Matrigel-coated transwell chambers (Becton Dickinson) with 8-µm pores, reconstituted with fresh medium for 2 h. Cells (2 × 104 ml−1 in 0.5 ml serum-free MEM in 12-well plates) were added to the upper chambers, and 1 ml MEM supplemented with 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 0.4% crystal violet for 2 h. Non-migrating cells were removed with a cotton swab from the upper side of the filter. The filter was mounted on a glass microscope slide, and cells were quantified by using ImageJ software. Results were expressed as the mean number of migrated cells normalized to the number of live cells cultured in parallel. Cell cycle analysis was performed as previously described. 72

Soft agar colony–formation assay

Two thousand viable cells in 1.5 ml of culture medium containing 1% glutamine, antibiotics, and 0.2% soft agar were layered on 0.5% solidified agar in IMDM culture medium in 6-well plates, incubated at 37 °C for 2 weeks, and stained with MTT reagent. Colony foci were counted by light microscopy (magnification 4×). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Mouse xenografts and immunohistochemical analyses

All animal experiments were approved by the St. Jude Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male ~6-week-old immunodeficient NCr nude mice (Taconic Farms, Hudson, NY) (5 per group) were inoculated subcutaneously with 1 × 106 cells in 200 µl of 1× PBS. After 2 weeks, animals were randomly divided into two groups per cell line. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with doxorubicin hydrochloride (carboxylate form; Sigma) 0.5 mg/kg or with vehicle three times weekly for 2 weeks. Tumor volume (maximal length x width x height) was measured every two days.

The LabVision 720 IHC Stainer (ThermoShandon, Fremont, CA) was used for immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissue. Tissue samples on slides were incubated for 120 min with primary antibodies (anti-MDR1 [sc-55510], Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:100; or anti-cleaved caspase 3 [CP229C], BioCare Medicinal, Concord, CA, 1:100) and then for 30 min with secondary antibodies (rodent anti-mouse, rodent anti-rabbit [BioCare Medical; RMR622L], donkey anti-goat polymer-HRP [Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-2042], and Quanto mouse on mouse-HRP [Thermo Fisher, Fremont, CA; TL-060-QHDM]). The stained slides were counterstained with DAB chromogen and hematoxylin (ThermoShandon), evaluated histologically for proteins of interest by two independent, blinded observers, and scored according to intensity of staining (0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. Sample and control values were compared as indicated in the figure legends by using the two-tailed Student's t-test, and p ≤ 0.05 (* or #) was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Moore and Hongbing Wang for plasmids; the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Shared Resource, the St. Jude Animal Resources Center and Veterinary Pathology Core for technical assistance; other members of the Chen group and Drs. Yong Li, John Schuetz, and Kip Guy for valuable discussions; and Sharon Naron for editing the manuscript.

Support: This work was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH), National Cancer Institute grant P30CA027165, National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM086415, the Hilfe für krebskranke Kinder Frankfurt e.V., the Frankfurter Stiftung für krebskranke Kinder, and the Kent Cancer Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- 1.Chen Y, Tang Y, Guo C, Wang J, Boral D, Nie D. Nuclear receptors in the multidrug resistance through the regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1112–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Huang W, Chua SS, Wei P, Moore DD. Modulation of Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity by the Xenobiotic Receptor CAR. Science. 2002;298:422–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1073502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fojo T. Multiple paths to a drug resistance phenotype: Mutations, translocations, deletions and amplification of coding genes or promoter regions, epigenetic changes and microRNAs. Drug Resist Updat. 2007;10:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennecke J, Cohen S. Towards a complete description of the microRNA complement of animal genomes. Genome Biol. 2003;4:228. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabbri M, Croce CM. Role of microRNAs in lymphoid biology and disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2011;18:266–272. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283476012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blower PE, Chung JH, Verducci JS, Lin S, Park JK, Dai Z, et al. MicroRNAs modulate the chemosensitivity of tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Passetti F, Ferreira CG, Costa FF. The impact of microRNAs and alternative splicing in pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moitra K, Im K, Limpert K, Borsa A, Sawitzke J, Robey R, et al. Differential Gene and MicroRNA Expression between Etoposide Resistant and Etoposide Sensitive MCF7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haenisch S, Cascorbi I. miRNAs as mediators of drug resistance. Epigenomics. 2012;4:369–381. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodzic J, Giovannetti E, Calvo BD, Adema AD, Peters GJ. Regulation of Deoxycytidine Kinase Expression and Sensitivity to Gemcitabine by Micro-RNA 330 and Promoter Methylation in Cancer Cells. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30:1214–1222. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.629271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Jaarsveld MT, Helleman J, Boersma AW, van Kuijk PF, van Ijcken WF, Despierre E, et al. miR-141 regulates KEAP1 and modulates cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:203–216. doi: 10.1038/nrc1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manohar CF, Bray JA, Salwen HR, Madafiglio J, Cheng A, Flemming C, et al. MYCN-mediated regulation of the MRP1 promoter in human neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:753–762. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porro A, Chrochemore C, Cambuli F, Iraci N, Contestabile A, Perini G. Nitric oxide control of MYCN expression and multi drug resistance genes in tumours of neural origin. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:431–439. doi: 10.2174/138161210790232112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porro A, Haber M, Diolaiti D, Iraci N, Henderson M, Gherardi S, et al. Direct and Coordinate Regulation of ATP-binding Cassette Transporter Genes by Myc Factors Generates Specific Transcription Signatures That Significantly Affect the Chemoresistance Phenotype of Cancer Cells. J Biolog Chem. 2010;285:19532–19543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teitz T, Wei T, Valentine MB, Vanin EF, Grenet J, Valentine VA, et al. Caspase 8 is deleted or silenced preferentially in childhood neuroblastomas with amplification of MYCN. Nat Med. 2000;6:529–535. doi: 10.1038/75007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlet J, Schnekenburger M, Brown KW, Diederich M. DNA demethylation increases sensitivity of neuroblastoma cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray I, Bryan K, Prenter S, Buckley PG, Foley NH, Murphy DM, et al. Widespread Dysregulation of MiRNAs by MYCN Amplification and Chromosomal Imbalances in Neuroblastoma: Association of miRNA Expression with Survival. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7850–e7860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Stallings RL. Differential Patterns of MicroRNA Expression in Neuroblastoma Are Correlated with Prognosis, Differentiation, and Apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:976–983. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buckley PG, Alcock L, Bryan K, Bray I, Schulte JH, Schramm A, et al. Chromosomal and MicroRNA Expression Patterns Reveal Biologically Distinct Subgroups of 11q− Neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2971–2978. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulte JH, Schowe B, Mestdagh P, Kaderali L, Kalaghatgi P, Schlierf S, et al. Accurate prediction of neuroblastoma outcome based on miRNA expression profiles. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2374–2385. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balaguer F, Link A, Lozano JJ, Cuatrecasas M, Nagasaka T, Boland CR, et al. Epigenetic Silencing of miR-137 Is an Early Event in Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6609–6618. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandres E, Agirre X, Bitarte N, Ramirez N, Zarate R, Roman-Gomez J, et al. Epigenetic regulation of microRNA expression in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2737–2743. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Q, Chen X, Zhang M, Fan Q, Luo S, Cao X. miR-137 is frequently down-regulated in gastric cancer and is a negative regulator of Cdc42. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2009–2016. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozaki K-i, Imoto I, Mogi S, Omura K, Inazawa J. Exploration of Tumor-Suppressive MicroRNAs Silenced by DNA Hypermethylation in Oral Cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2094–2105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langevin SM, Stone RA, Bunker CH, Lyons-Weiler MA, LaFramboise WA, Kelly L, et al. MicroRNA-137 promoter methylation is associated with poorer overall survival in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2011;117:1454–1462. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cinatl J, Vogel J-U, Cinatl J, Weber B, Rabenau H, Novak M, et al. Long-term productive human cytomegalovirus infection of a human neuroblastoma cell line. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:90–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960103)65:1<90::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michaelis M, Rothweiler F, Klassert D, von Deimling A, Weber K, Fehse B, et al. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by the murine double minute 2 antagonist nutlin-3. Cancer Res. 2009;69:416–421. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Wang Q, Yao X, Li Y. Induction of CYP3A4 and MDR1 gene expression by baicalin, baicalein, chlorogenic acid, and ginsenoside Rf through constitutive androstane receptor- and pregnane X receptor-mediated pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;640:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faucette SR, Sueyoshi T, Smith CM, Negishi M, LeCluyse EL, Wang H. Differential Regulation of Hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 Genes by Constitutive Androstane Receptor but Not Pregnane X Receptor. J Pharmacol and Exp Ther. 2006;317:1200–1209. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baskin-Bey ES, Huang W, Ishimura N, Isomoto H, Bronk SF, Braley K, et al. Constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) ligand, TCPOBOP, attenuates Fas-induced murine liver injury by altering Bcl-2 proteins. Hepatology. 2006;44:252–262. doi: 10.1002/hep.21236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji M, Li J, Yu H, Ma D, Ye J, Sun X, et al. Simultaneous targeting of MCL1 and ABCB1 as a novel strategy to overcome drug resistance in human leukaemia. Bri J Haematol. 2009;145:648–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wertz IE, Kusam S, Lam C, Okamoto T, Sandoval W, Anderson DJ, et al. Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature. 2011;471:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature09779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beilke LD, Aleksunes LM, Olson ER, Besselsen DG, Klaassen CD, Dvorak K, et al. Decreased apoptosis during CAR-mediated hepatoprotection against lithocholic acid-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Lett. 2009;188:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benbow U, Maitra R, Hamilton JW, Brinckerhoff CE. Selective Modulation of Collagenase 1 Gene Expression by the Chemotherapeutic Agent Doxorubicin. Clinical Cancer Res. 1999;5:203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiebig A, Zhu W, Hollerbach C, Leber B, Andrews D. Bcl-XL is qualitatively different from and ten times more effective than Bcl-2 when expressed in a breast cancer cell line. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lahoti T, Patel D, Thekkemadom V, Beckett R, Ray SD. Doxorubicin-Induced In Vivo Nephrotoxicity Involves Oxidative Stress-Mediated Multiple Pro- And Anti-Apoptotic Signaling Pathways. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2012;9:282–295. doi: 10.2174/156720212803530636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Faucette S, Sueyoshi T, Moore R, Ferguson S, Negishi M, et al. A Novel Distal Enhancer Module Regulated by Pregnane X Receptor/Constitutive Androstane Receptor Is Essential for the Maximal Induction of CYP2B6 Gene Expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14146–14152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takwi AAL, Li Y, Becker Buscaglia LE, Zhang J, Choudhury S, Park AK, et al. A statin-regulated microRNA represses human c-Myc expression and function. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:896–909. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201101045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bemis LT, Chen R, Amato CM, Classen EH, Robinson SE, Coffey DG, et al. MicroRNA-137 Targets Microphthalmia-Associated Transcription Factor in Melanoma Cell Lines. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1362–1368. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu M, Lang N, Qiu M, Xu F, Li Q, Tang Q, et al. miR-137 targets Cdc42 expression, induces cell cycle G1 arrest and inhibits invasion in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1269–1279. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen F, Chu S, Bence AK, Bailey B, Xue X, Erickson PA, et al. Quantitation of Doxorubicin Uptake, Efflux, and Modulation of Multidrug Resistance (MDR) in MDR Human Cancer Cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:95–102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tabe Y, Konopleva M, Contractor R, Munsell M, Schober WD, Jin L, et al. Up-regulation of MDR1 and induction of doxorubicin resistance by histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide (FK228) and ATRA in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2006;107:1546–1554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, Mao W, Ding B, Liang C-s. ERKs/p53 signal transduction pathway is involved in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells and cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1956–H1965. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clair SS, Giono L, Varmeh-Ziaie S, Resnick-Silverman L, Liu W-j, Padi A, et al. DNA Damage-Induced Downregulation of Cdc25C Is Mediated by p53 via Two Independent Mechanisms: One Involves Direct Binding to the cdc25C Promoter. Mol Cell. 2004;16:725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Estève P-O, Chin HG, Pradhan S. Human maintenance DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase and p53 modulate expression of p53-repressed promoters. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1000–1005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407729102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tojima H, Kakizaki S, Yamazaki Y, Takizawa D, Horiguchi N, Sato K, et al. Ligand dependent hepatic gene expression profiles of nuclear receptors CAR and PXR. Toxicol Lett. 2012;212:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lujambio A. CpG Island Hypermethylation of Tumor Suppressor microRNAs in Human Cancer. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1454–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langevin SM, Stone RA, Bunker CH, Grandis JR, Sobol RW, Taioli E. MicroRNA-137 promoter methylation in oral rinses from patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is associated with gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:864–870. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu M, Lang N, Qiu M, Xu F, Li Q, Tang Q, et al. miR-137 targets Cdc42 expression, induces cell cycle G1 arrest and inhibits invasion in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1269–1279. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y, Li Y, Lou G, Zhao L, Xu Z, Zhang Y, et al. MiR-137 targets estrogen-related receptor alpha and impairs the proliferative and migratory capacity of breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The Vitravene Study Group. Safety of intravitreous fomivirsen for treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:484–498. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elmen J, Lindow M, Schutz S, Lawrence M, Petri A, Obad S, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krutzfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, Rajeev KG, Tuschl T, Manoharan M, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with /`antagomirs/'. Nature. 2005;438:685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haldar S, Basu A. Modulation of MicroRNAs by Chemical Carcinogens and Anticancer Drugs in Human Cancer: Potential Inkling to Therapeutic Advantage. Mol Cell Pharmacol. 2011;3:135–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kotchetkov R, Cinatl J, Blaheta R, Vogel J-U, Karaskova J, Squire J, et al. Development of resistance to vincristine and doxorubicin in neuroblastoma alters malignant properties and induces additional karyotype changes: A preclinical model. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:36–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kotchetkov R, Driever PH, Cinatl J, Michaelis M, Karaskova J, Blaheta R, et al. Increased malignant behavior in neuroblastoma cells with acquired multi-drug resistance does not depend on P-gp expression. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1029–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Michaelis M, Cinatl Jaroslav, Cinatl J, Anand P, Rothweiler F, Kotchetkov R, Deimling Av, et al. Onconase induces caspase-independent cell death in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2007;250:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu Z, Li Y, Takwi A, Li B, Zhang J, Conklin DJ, et al. miR-301a as an NF-[kappa]B activator in pancreatic cancer cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:57–67. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishan A, Ganapathi R. Laser Flow Cytometric Studies on the Intracellular Fluorescence of Anthracyclines. Cancer Res. 1980;40:3895–3900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krishan A, Sauerteig A, Wellham LL. Flow Cytometric Studies on Modulation of Cellular Adriamycin Retention by Phenothiazines. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1046–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Venne A, Li S, Mandeville R, Kabanov A, Alakhov V. Hypersensitizing Effect of Pluronic L61 on Cytotoxic Activity, Transport, and Subcellular Distribution of Doxorubicin in Multiple Drug-resistant Cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3626–3629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cherian MT, Wilson EM, Shapiro DJ. A Competitive Inhibitor That Reduces Recruitment of Androgen Receptor to Androgen-responsive Genes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23368–23380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.344671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen T, Tompkins LM, Li L, Li H, Kim G, Zheng Y, et al. A Single Amino Acid Controls the Functional Switch of Human Constitutive Androstane Receptor (CAR) 1 to the Xenobiotic-Sensitive Splicing Variant CAR3. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:106–115. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin W, Wu J, Dong H, Bouck D, Zeng F-Y, Chen T. Cyclin-dependent Kinase 2 Negatively Regulates Human Pregnane X Receptor-mediated CYP3A4 Gene Expression in HepG2 Liver Carcinoma Cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30650–30657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806132200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.