Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) agonists like pioglitazone (PGZ) are effective antidiabetic drugs, but they induce fluid retention and body weight (BW) gain. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) inhibitors are antidiabetic drugs that enhance renal Na+ and fluid excretion. Therefore, we examined whether the DPP IV inhibitor alogliptin (ALG) ameliorates PGZ-induced BW gain. Male Sv129 mice were treated with vehicle (repelleted diet), PGZ (220 mg/kg diet), ALG (300 mg/kg diet), or a combination of PGZ and ALG (PGZ + ALG) for 14 days. PGZ + ALG prevented the increase in BW observed with PGZ but did not attenuate the increase in body fluid content determined by bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS). BIS revealed that ALG alone had no effect on fat mass (FM) but enhanced the FM-lowering effect of PGZ; MRI analysis confirmed the latter and showed reductions in visceral and inguinal subcutaneous (sc) white adipose tissue (WAT). ALG but not PGZ decreased food intake and plasma free fatty acid concentrations. Conversely, PGZ but not ALG increased mRNA expression of thermogenesis mediator uncoupling protein 1 in epididymal WAT. Adding ALG to PGZ treatment increased the abundance of multilocular cell islets in sc WAT, and PGZ + ALG increased the expression of brown-fat-like “beige” cell marker TMEM26 in sc WAT and interscapular brown adipose tissue and increased rectal temperature vs. vehicle. In summary, DPP IV inhibition did not attenuate PPARγ agonist-induced fluid retention but prevented BW gain by reducing FM. This involved ALG inhibition of food intake and was associated with food intake-independent synergistic effects of PPARγ agonism and DPP-IV inhibition on beige/brown fat cells and thermogenesis.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, edema, white adipose tissue, adipocyte size, brown adipose tissue, beige fat

agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) are antidiabetic drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes. In addition to increasing insulin sensitivity, these agents have favorable effects on lipid metabolism and inflammation (3, 47). However, PPARγ agonists can induce fluid retention and body weight (BW) gain, which are important clinical limitations, especially in patients with heart failure (29). PPARγ in the renal collecting duct has been implicated in PPARγ agonist-induced fluid retention and BW gain, although the molecular mechanism remains unclear (15, 50).

More recently, dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) inhibitors have been developed as new antidiabetic drugs (56). DPP IV is a glycoprotein detectable in plasma as well as in cell membranes of intestinal epithelial cells, inflammatory cells, and adipose tissue and cleaves NH2-terminal dipeptides from a variety of substrates (56). Two substrates of DPP IV, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (so-called incretin hormones), are released from the intestinal mucosa into the systemic circulation in response to glucose intake and increase postprandial insulin secretion by stimulation of pancreatic islet β-cells (9, 46). DPP IV inhibitors suppress the breakdown of these incretins, thereby acting as stimulators of insulin release (9). In addition to targeting pancreatic islets, DPP IV inhibition has favorable effects on other tissues, including the kidney, where DPP IV is strongly expressed in proximal tubular brush border and where inhibition of the enzyme induces acute diuretic and natriuretic effects (6, 33, 37). These effects on the kidney occur independent of the presence of the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) (37) and may involve inhibitory effects on the Na-H-exchanger NHE3 (13, 14, 33, 37). Thus, whereas both principles are effective antidiabetics, the natriuretic and diuretic effect of DPP IV inhibition contrasts the fluid retention induced by PPARγ agonism.

Therefore, in the present study, we tested the hypothesis that the high-affinity, high-specificity DPP IV inhibitor alogliptin (ALG) ameliorates PPARγ agonist pioglitazone (PGZ)-induced BW gain via a reduction in body fluid volume. Since the effects of DPP IV inhibition and PPARγ agonism on body fluid homeostasis occur independent of their antihyperglycemic properties and to prevent confounding effects of glucose-lowering on body fluid homeostasis, we tested this issue in nondiabetic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and study design.

All animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System. Male Sv129 mice (10 wk of age) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and housed in standard rodent cages on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to food (1% K+, 0.4% Na+, 4.4% fat; Harlan Teklad TD.7001) and water. At 20–24 wk of age (average BW 28.8 ± 0.3 g) the mice were separated into four groups of matched BW (n = 8–10/group), vehicle (Veh), PGZ, ALG, and combination of pioglitazone and alogliptine (PGZ + ALG). After basal measurements, the Veh group was fed the repelleted standard diet. The PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG groups were fed the same repelleted standard diet that included PGZ [220 mg/kg diet (50); Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Deerfield, IL], ALG [300 mg/kg diet of free base (26); Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA], or a combination of both PGZ (220 mg/kg diet) and ALG (300 mg/kg diet), respectively. This corresponded to daily doses of ALG and PGZ of 35–40 and 25–30 mg/kg BW, respectively.

BW and food and fluid intake.

BW was determined daily at the same time before and during 14 days of treatment. Daily intake of food and fluid was also determined over the whole treatment period, whereas the mice were maintained in their standard rodent cages.

Body fluid and fat analysis by bioimpedance spectroscopy.

After 14 days treatment, bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) was performed under terminal anesthesia with ketamine (100 mg/ml, 2.5 ml/kg BW ip) and xylazine (20 mg/dl, 2.5 ml/kg BW ip) using the ImpediVet BIS1 system (ImpediMed, San Diego, CA) to analyze total body water (TBW), extracellular fluid (ECF), intracellular fluid (ICF), and fat mass (FM). BIS determines body composition on the basis of its electrical characteristics in response to the application of low-amplitude alternating electrical currents (4). BIS has been used extensively for fluid volume and FM determination in humans (18) and more recently for fluid volume evaluation in rats and mice (4, 42). Briefly, animals were shaved in the areas where the four electrodes were placed to gain good skin contact. The bioimpedance data were converted to appropriate values using the specific resistivity coefficients of the extracellular (Re) and intracellular (Ri) compartment (Re: 421.3; Ri: 1,053.7) of Sv129 mice. These coefficients were precalculated using all Veh group records to average normal TBW/BW and ECF/BW ratios of 58 and 20%, respectively, as described previously in C57BL6 mice (4). Results were expressed as percentage of total BW and in absolute terms (ml or g). We used MRI (see below) (28) as an independent method to confirm unexpected results on FM measured by BIS.

Hematocrit and plasma analysis.

After completing BIS and while still under terminal anesthesia, nonfasted animals had blood collected by retrobulbar plexus puncture. Hematocrit was measured after centrifugation. Plasma DPP IV activity was measured using a homogeneous luminescent assay, DPP IV Protease Assay (Promega, WI), as described (37). Data were expressed relative to Veh, set as 100%. Plasma free fatty acid (FFA) concentration was determined using an enzyme-based FFA quantification kit (Biovision). Plasma glucose was determined by the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method (Infinity, Thermo Electron).

Analysis of FM and fat distribution by MRI.

In a separate set of mice and a 16-day treatment with PGZ or PGZ + ALG, MRI was used to determine FM and fat distribution using a Bruker 7T/20 MRI scanner with a magnetic field strength of 7.0 Tesla (Bruker-Biospin, Ettlingen, Germany) immediately after euthanasia with CO2. Contiguous coronal slices were acquired using a multi-slice, multi-echo sequence (repetition time/echo time = 1,115.4 ms/10.5 ms) with up to 65 coronal planes, depending on the size of the mouse, each 0.5 mm thick and two averages. The field of view was 9 × 3.6 cm, with a matrix size of 256 × 128 complex points. Using Amira 5.4.2 software (Visage Imaging, Berlin, Germany), body FM, body lean mass, and abdominal visceral and subcutaneous FM were analyzed independently by two investigators, as described previously (22). The abdominal region between the xiphisternum and the base of tail was included in visceral and subcutaneous FM measurements.

Determination of adipocyte size.

Adipocyte size was measured in frozen adipose tissue (Veh, PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG) and fresh adipose tissue (PGZ and PGZ + ALG). Frozen adipose tissue refers to epididymal white adipose tissue (WAT), which was excised during anesthesia after 14 days of treatment (after BIS measurement) and being immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in −80°C freezer without fixation at time of harvest. Fresh adipose tissue refers to epididymal and inguinal subcutaneous WAT, which was excised from mice after 16 days treatment (after MRI measurement) followed by immediate fixation. Both frozen and fresh tissues were fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin embedded fat tissue was cut into 5-μm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Pictures were taken on an Olympus IX81 microscope, and adipocyte cross-sectional area was determined using Image J 1.45s (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), as described previously (11). At least 300 adipocytes per mouse were analyzed.

Expression analysis of transmembrane protein 26 in adipose tissue by immunofluorescence.

Inguinal and retroperitoneal WAT and interscapular brown adipose tissue (BAT) were excised after 16 days of treatment, immediately fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded fat tissue was cut into 5-μm sections and prepared to analyze transmembrane protein 26 (TMEM26) expression by immunofluorescence, as described previously (54). Rabbit anti-TMEM26 (1:50; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (1:200; Invitrogen) were used. Samples were visualized with fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and quantified by Image J, as described previously (27). Fluorescence signal was quantified by scoring the percent of pixels per image that exceeded an intensity threshold. Data were collected from at least 40 random fields per group (n = 4–5/group) with a ×20 objective lens.

Uncoupling protein 1 mRNA expression analysis in epididymal WAT.

After 14 days of treatment, epididymal adipose tissue was excised under terminal anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine (see above) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) mRNA expression analysis was performed using an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System, as described previously (51). Amplification efficiencies were normalized against the fat tissue housekeeping gene 36B4 (12), the expression of which was not affected by any treatment (data not shown; in contrast, expression of rpl19 and cyclophilin was affected by treatment, and therefore, it was not used). The specific primer sequences were as follows: UCP1: forward ACTGCCACACCTCCAGTCATT, reverse CTTTGCCTCACTCAGGATTGG; 36B4: forward TAAAGACTGGAGACAAGGTG, reverse GTGTAGTCAGTCTCCACAGA. Each RNA sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Pair-feeding study.

In a separate set of male Sv129 mice using the same diets, pair-feeding was performed to further delineate the influence of the food intake-lowering effect of ALG on changes in BW and expression of TMEM26 in inguinal WAT and interscapular BAT and to determine effects of the drugs on rectal temperature. Pair-feeding was performed by giving the ALG-treated group free access to the diet and adjusting on a daily basis the amount of diet given to the other three groups. BW and food and fluid intake were determined as described for 16 days. Then the rectal temperature was determined twice in each mouse on 2 consecutive days during brief and standardized isoflurane anesthesia. Spontaneous urine samples were collected to determine concentrations of sodium, potassium, and creatinine in awake mice, and blood and fat tissue were collected under terminal anesthesia to determine hematocrit and analyze for adipocyte size and/or TMEM26 expression, respectively, as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical differences were analyzed by Student's t-test in studies with two groups only (for comparison between PGZ + ALG vs. PGZ alone) or ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc testing (Holm-Sidak) for pairwise comparisons and for comparison with vehicle group when more than two groups were compared. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

ALG prevented the PGZ-induced increase in BW.

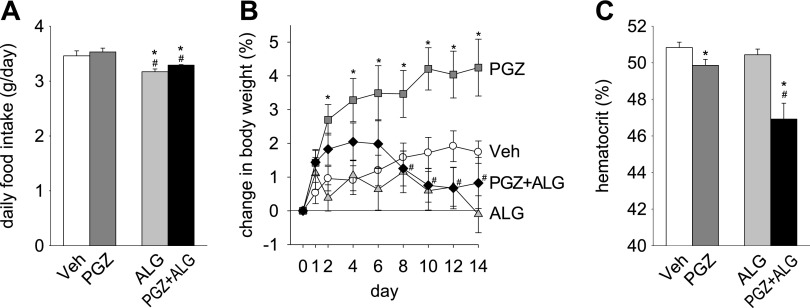

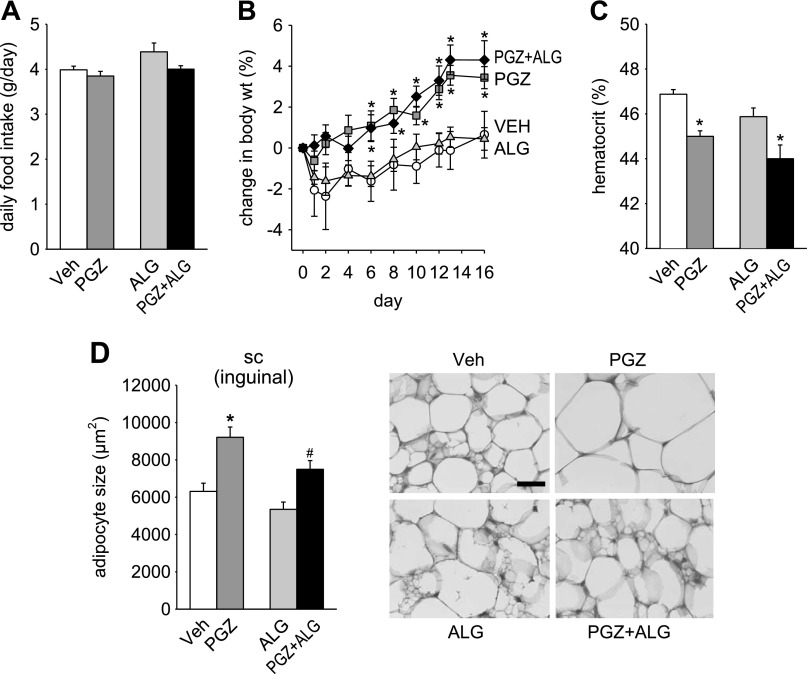

Basal BW before treatment was not different among the groups [Veh 28.7 ± 0.8 g, PGZ 28.8 ± 0.6 g, ALG 28.7 ± 0.7 g, and PGZ + ALG 28.9 ± 0.5 g; n = 8–10/group, not significant (NS)]. PGZ increased BW compared with Veh (Fig. 1B). ALG did not siginificantly lower BW compared with Veh (Fig. 1B). However, ALG added to PGZ prevented the increase in BW seen with PGZ alone (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Alogliptin (ALG) prevented the pioglitazone (PGZ)-induced increase in body weight (BW). Effect of 14-day treatment with PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG on food intake (A), BW (B), and hematocrit (C). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (Veh); #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; n = 8–10/group.

PGZ did not significantly change the mean daily food or fluid intake over the 14-day period compared with Veh [Fig. 1A (fluid intake not shown)]. By comparison, ALG lowered food intake in the presence and absence of PGZ by 6–8% (Fig. 1A). Fluid intake was not significantly changed by ALG alone or cotreatment with PGZ (data not shown). Thus the BW-lowering effect of ALG was associated with a lower food intake.

ALG did not attenuate PGZ-induced fluid retention.

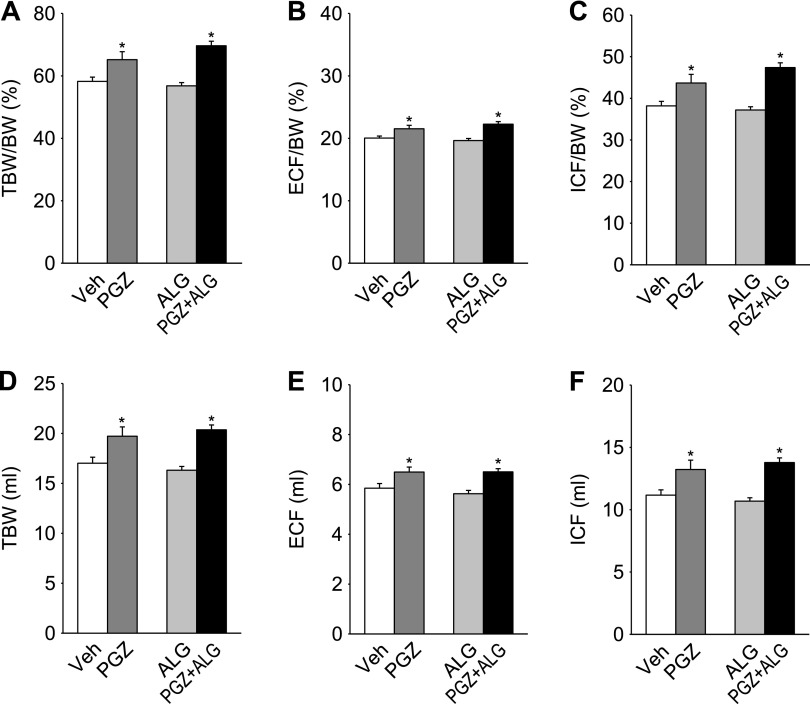

A decrease in hematocrit has been related to fluid retention and increased vascular permeability in response to PPARγ agonists (43, 50). PGZ decreased hematocrit compared with Veh, whereas ALG alone had no effect (Fig. 1C). PGZ + ALG decreased hematocrit to a greater degree than PGZ alone (Fig. 1C). As determined by BIS, PGZ significantly increased TBW/BW, ECF/BW, and ICF/BW compared with Veh, whereas ALG alone had no effect on these parameters (Fig. 2, A–C). PGZ + ALG increased TBW/BW, ECF/BW, and ICF/BW to a similar degree as PGZ alone (Fig. 2, A–C). Similar results were obtained for absolute values of TBW, ECF, and ICF (Fig. 2, D–F). Consistent with the results for hematocrit, the BIS data demonstrate that PGZ induced fluid retention and that cotreatment with ALG did not attenuate this response. Therefore, the ALG-induced prevention of BW gain in response to PGZ was not due to an effect on fluid retention.

Fig. 2.

ALG did not attenuate PGZ-induced fluid retention. Bioimpedance analysis of total body water (TBW), extracellular fluid (ECF), and intracellular fluid (ICF) after 14-day treatment with PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG. A–C: results relative to body weight. D–F: absolute values. *P < 0.05 vs. Veh; n = 9–10/group.

ALG prevented PGZ-induced BW gain by reducing visceral and subcutaneous FM.

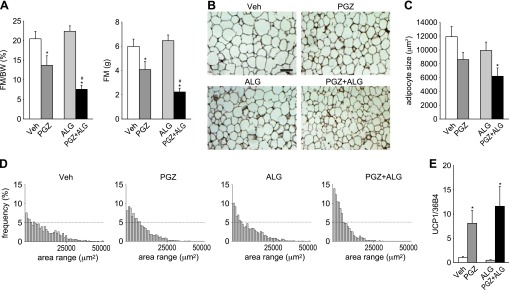

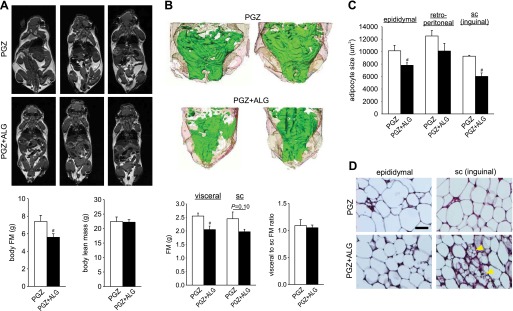

It has been reported that PGZ decreases adipocyte size in obese rats (7) and ALG ameliorates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy (39). Therefore, we used BIS to determine whether PGZ and/or ALG altered FM. We found that PGZ significantly decreased FM relative to BW and in absolute terms, whereas ALG alone had no effect compared with Veh (Fig. 3A). Notably, PGZ + ALG further decreased FM compared with PGZ alone (Fig. 3A). These BIS results indicated that PGZ decreased FM and that ALG potentiated this effect on FM. To confirm the BIS results on FM by an independent method, we used MRI, an established evaluation tool for FM (28), in a separate set of mice after 16-day treatment with PGZ vs. PGZ + ALG. Similar to BIS data (Fig. 3A), PGZ + ALG decreased absolute FM significantly (Fig. 4A) compared with PGZ alone. In comparison, body lean mass was similar between PGZ and PGZ + ALG (Fig. 4A). PPARγ agonists, like PGZ, can induce a shift of fat distribution from visceral to subcutaneous adipose tissue, which is associated with improvement of insulin resistance (25). Therefore, we measured visceral and subcutaneous FM using MRI. PGZ + ALG decreased visceral FM significantly and subcutaneous FM numerically compared with PGZ alone such that the visceral/subcutaneous FM ratio was similar among the groups (Fig. 4B). The studies show that the reduction in body FM explained the ALG-induced prevention of BW gain in response to PGZ and that both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue were affected similarly.

Fig. 3.

Fat mass (FM) reduction explained the prevention of PGZ-induced BW gain by ALG. A: bioimpedance analysis of FM after 14-day treatment with PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG. Left: FM relative to BW; right: absolute values. *P < 0.05 vs. Veh; #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; n = 9–10/group. B: hematoxylin and eosin staining of epididymal white adipose tissue (WAT). Scale bar, 200 μm. C and D: quantification (C) and histogram (D) of adipose cell cross-sectional area after 14-day treatment with PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG. E: PGZ increases epididymal WAT mRNA expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). *P < 0.05 vs. Veh; n = 4–5/group.

Fig. 4.

ALG reduced body FM and adipocyte size in epididymal and subcutaneous (sc) inguinal WAT in the presence of PGZ. Comparison of FM and adipocyte size between PGZ and PGZ + ALG. A, top: MRI images across the bodies of mice after 16-day treatment with PGZ and PGZ + ALG. White areas indicate fat tissue, and each image is a different mouse. A, bottom: body FM (left) and body lean mass (right) calculated by MRI image using software. B, top: 3-dimensional images of abdominal region reconstructed by 2-dimensional MRI images using software. Green areas indicate visceral WAT, and light brown areas indicate sc WAT in PGZ and PGZ + ALG. B, bottom: visceral and sc FM (left) and visceral-to-sc FM ratio (right). C: quantification of adipose cell cross-sectional area in epididymal, retroperitoneal, and inguinal sc WAT in PGZ and PGZ + ALG. D: hematoxylin and eosin staining of epididymal and inguinal sc WAT in PGZ and PGZ + ALG. Islets of multilocular fat cells within inguinal sc white fat depot are shown in PGZ + ALG (arrowheads). Scale, 100 μm. #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; n = 5–6/group.

Synergistic effect of ALG and PGZ on adipocyte size in epididymal WAT.

To analyze further the effect of ALG and PGZ on adipose tissue, we examined adipocyte size in epididymal WAT (Fig. 3, B–D). PGZ or ALG alone did not significantly change mean adipocyte size (Fig. 3C). In comparison, PGZ + ALG decreased adipocyte size significantly compared with Veh (Fig. 3C); a lower mean value of adipocyte size in response to PGZ + ALG was associated with a redistribution to smaller adipocytes (Fig. 3D).

Analyses in a separate set of mice (after MRI) revealed that, in addition to epididymal WAT, inguinal subcutaneous adipocyte size was also decreased significantly in PGZ + ALG compared with PGZ alone (Fig. 4, C and D). These results indicated that FM reduction in PGZ + ALG vs. PGZ alone was associated with a shift to smaller adipocytes in epididymal and subcutaneous inguinal WAT.

PGZ, but not ALG, lowered epididymal WAT mRNA expression of UCP1.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis in epididymal WAT revealed that PGZ alone and together with ALG increased the mRNA expression of the thermogenesis mediator UCP1 (54) vs. Veh, whereas ALG alone had no effect (Fig. 3E).

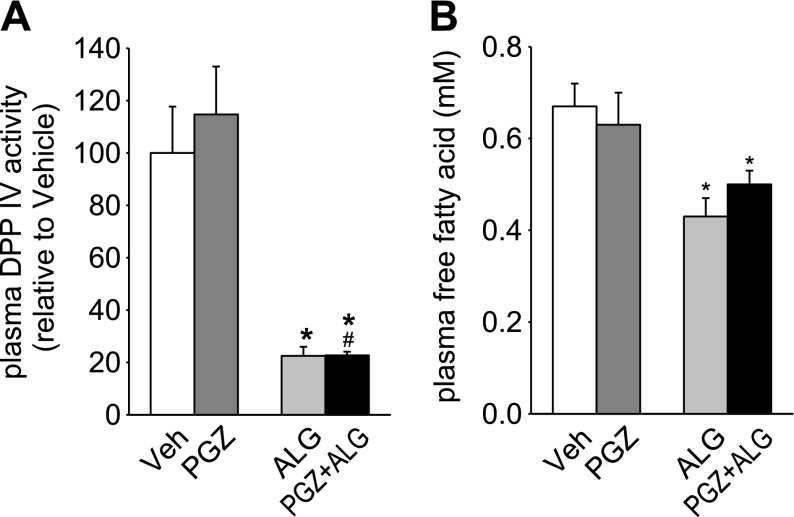

ALG, but not PGZ, reduced DPP IV activity and the concentration of FFA in plasma.

Circulating DPP IV levels and activity are positively correlated with adipocyte size (21), and plasma FFA concentration is known to positively associate with FM (19). We observed that ALG decreased plasma DPP IV activity and plasma FFA concentrations in the presence and absence of PGZ, whereas PGZ alone had no effect (Fig. 5, A and B). Blood glucose concentrations were not significantly different between ALG, PGZ, and PGZ + ALG vs. Veh (11.5 ± 0.5, 12.5 ± 0.5, and 12.1 ± 0.4 vs. 12.9 ± 0.4 mM, NS) and difficult to interpret since measurements were performed in nonfasted animals and under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia, which is known to acutely increase blood glucose levels.

Fig. 5.

ALG, but not PGZ, reduced dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP IV) activity and the concentration of free fatty acid in plasma. Effect of 14-day treatment with PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG on plasma DPP IV activity (A) and plasma free fatty acid (B). *P < 0.05 vs. Veh; #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; n = 7–10/group.

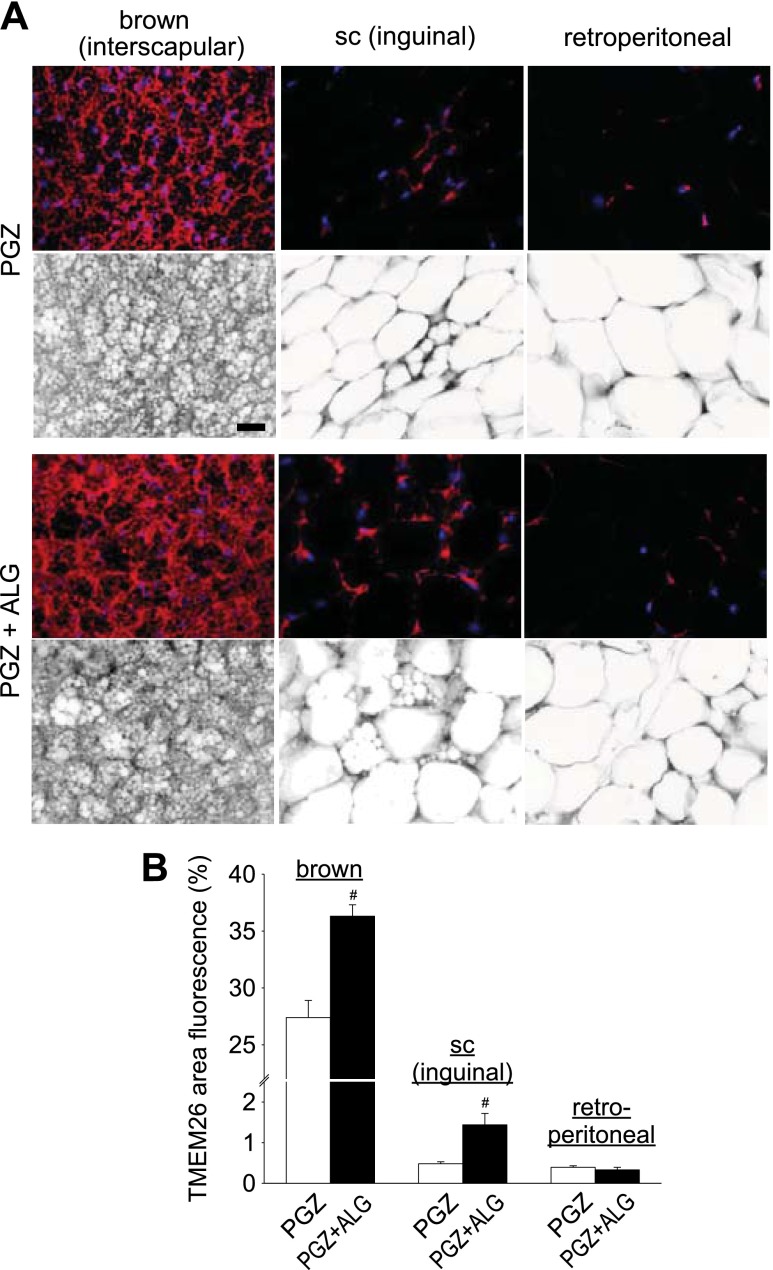

ALG increases brown-fat-like “beige” cells in inguinal subcutaneous WAT in the presence of PGZ.

Brown fat-like “beige” cells, which show islets of multilocular cells, can be found in inguinal subcutaneous WAT in mice and induce thermogenesis like classical BAT (54). We found that PGZ + ALG increased the abundance of multilocular brown fat-like cells in inguinal subcutaneous WAT compared with mice treated with PGZ alone (Fig. 4D). To follow up on these findings, we examined the expression of beige cell marker TMEM26 (54) in inguinal subcutaneous and retroperitoneal WAT as well as interscapular BAT. Compared with PGZ alone, PGZ + ALG significantly increased the percent area of TMEM26 fluorescence in inguinal subcutaneous WAT and interscapular BAT (Fig. 6, A and B). By comparison, TMEM26 expression in retroperitoneal WAT was similar among the groups (Fig. 6, A and B). The mean intensity of TMEM26 was similarly altered such that the ratio of the mean intensity to percent area of TMEM26 was similar between PGZ alone and PGZ + ALG (data not shown). These data are consistent with the notion that ALG increased the abundance of brown fat-like beige cells in inguinal subcutaneous WAT and possibly interscapular BAT in the presence of PGZ.

Fig. 6.

ALG enhanced beige cell marker transmembrane protein 26 (TMEM26) expression in interscapular brown adipose tissue (BAT) and inguinal sc WAT in the presence of PGZ. A: immunofluorescene double staining for TMEM26 and DAPI (nuclei marker) of interscapular BAT, inguinal sc WAT, and retroperitoneal WAT in PGZ and PGZ + ALG. Top: images under fluorescence mode; bottom: images under inverted mode. Each pair image (top and bottom) is the same area. Scale bar, 100 μm. B: TMEM26-positive area (%) of interscapular BAT, inguinal sc WAT, and retroperitoneal WAT in PGZ and PGZ + ALG. #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; n = 4–5/group.

Pair-feeding studies: role of food intake in ALG effects on BW and synergistic effects of ALG and PGZ on TMEM26 expression in interscapular BAT and subcutaneous inguinal WAT and rectal temperature.

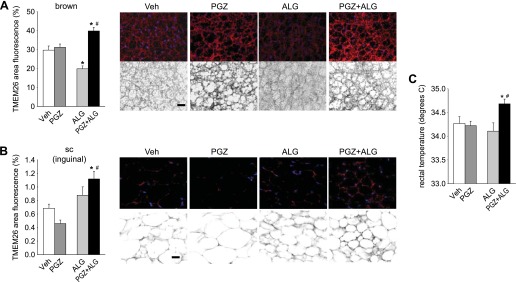

Basal BW before treatment was not different among the groups (Veh 32.8 ± 0.9 g, PGZ 32.4 ± 0.8 g, ALG 32.7 ± 0.5 g, and PGZ + ALG 32.3 ± 0.5 g; n = 8–9/group, NS). Pair feeding established similar food intake in all groups (Fig. 7A) and eliminated lower food intake as a confounding factor in response to ALG. The PGZ-induced increase in BW compared with Veh was maintained. As shown in Fig. 7B, pair feeding prevented the BW-lowering effect of ALG that was observed in non-pair-fed mice (for comparison, see Fig. 1B). Both PGZ and PGZ + ALG lowered hematocrit to a similar extent vs. vehicle (Fig. 7C), consistent with a similar fluid retention as proposed by BIS data in non-pair-fed mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 7.

Pair feeding prevented the BW-lowering effect of ALG. Effect of treatment with PGZ, ALG, and PGZ + ALG on food intake (A), BW (B), hematocrit (C), and adipocyte size in inguinal sc WAT (D). In D, quantification of adipose cell cross-sectional area (left) and representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (right) are shown. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (Veh); #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; n = 8–9/group.

As observed in non-pair-fed mice (Fig. 4C), PGZ + ALG lowered adipocyte size vs. PGZ in inguinal subcutaneous WAT (Fig. 7D). PGZ alone increased adipocyte size in this tissue vs. vehicle, whereas ALG alone was ineffective. As in non-pair-fed mice (Fig. 6), PGZ + ALG increased the percent area of TMEM26 fluorescence vs. PGZ in inguinal subcutaneous WAT and interscapular BAT (Fig. 8, A and B). Notably, the TMEM26 fluorescence signal was greater in PGZ + ALG vs. Veh in both tissues. ALG alone lowered the percent area of TMEM26 fluorescence in interscapular BAT and had no significant effect in inguinal subcutaneous WAT. By comparison and as observed in non-pair-fed mice (Fig. 6), TMEM26 expression in retroperitoneal WAT was not different among groups (not shown). These changes were associated with an increase in rectal temperature in PGZ + ALG vs. Veh, whereas PGZ and ALG alone were ineffective (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Synergistic effect of PGZ and ALG on beige cell marker TMEM26 expression in interscapular BAT and inguinal sc WAT and rectal temperature. A and B, left: quantification of TMEM26-positive area (%) of interscapular BAT and inguinal sc WAT is shown. A and B, right: immunofluorescene double staining for TMEM26 and DAPI is shown (nuclei marker). Top images in each treatment are those under fluorescence mode, and bottom images are those under inverted mode. Scale bar, 100 μm. C: rectal temperature determined under brief isoflurane anesthesia. #P < 0.05 vs. PGZ alone; *P < 0.05 vs. Veh; n = 8–10/group.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows for the first time that a DPP IV inhibitor can prevent the PPARγ agonist-induced BW gain due to a reduction in FM, but not in fluid retention. The FM reduction was associated with a reduction in adipocyte size, including epididymal and inguinal subcutaneous WAT. The reduction in BW was prevented by pair feeding, indicating a prominent role for the food intake-lowering effect of ALG. In addition, we show that a DPP IV inhibitor and PPARγ agonist together increase the expression of TMEM26, a marker of brown fat-like beige cells, in inguinal subcutaneous WAT and interscapular BAT, which is paralleled by an increase in rectal temperature, whereas each drug alone was ineffective. These effects occurred independent of the ALG effect on food intake.

ALG did not prevent PGZ-induced fluid retention. This was demonstrated unequivocally by measurement of hematocrit and body fluid content using BIS. We reported recently that acute inhibition of DPP IV activity by ALG induces diuresis and natriuresis (37), confirming previous studies (6, 33). The diuretic and natriuretic effect by ALG did not require an intact GLP-1R (37) and therefore may involve DPP IV substrates beyond GLP-1 [potential candidates include brain natriuretic peptide 1–32 (2)]. Chronic inhibition of DPP IV activity can also induce diuresis and natriuresis (13, 33). However, a study with the DPP IV inhibitor sitagliptin in rats indicated that diuretic and natriuretic effects decreased gradually after 3 days of treatment (total of 8 days of treatment) (33), which in part, may be due to the activation of compensatory antinatriuretic mechanisms. Consistent with similar food intake and steady-state conditions, we found similar urinary sodium and potassium to creatinine ratios in spontaneous urine samples in all groups during the 3rd wk of treatment in the pair-feeding studies (data not shown). Furthermore, we reported previously that ALG had no acute diuretic and natriuretic effect in diabetic db/db mice, although the drug was effective in nondiabetic db/− mice (37). Thus, the effect of DPP IV inhibition on renal excretion may depend on the duration of treatment and the metabolic status. Although further studies are needed to better understand these issues, the present studies do not support the notion that DPP IV inhibition can significantly affect PPARγ agonist-induced fluid retention.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the combined effect of a DPP IV inhibitor and a PPARγ agonist on FM. A recent report indicated the usefulness and reliability of BIS to detect changes in FM in rats by showing that FM measured by BIS was highly correlated with chemical carcass analysis (r2 = 0.966) (42). In the present study, we showed using BIS that PGZ alone and PGZ + ALG significantly reduced FM compared with Veh. We further confirmed the usefulness of BIS to detect changes in FM in the mouse by comparing the results with MRI, a gold standard for FM measurement (28). Both methods revealed that the application of ALG to PGZ-treated mice reduced FM/BW ratios and absolute FM by 20–46%. By comparison, ALG alone did not affect FM. These findings indicated a synergistic effect of ALG and PGZ on FM.

PPARγ agonists have been shown to enhance differentiation of preadipocytes into mature adipocytes and promote fatty acid storage in adipose tissue (24, 36). PPARγ agonists have also been described to decrease the number of large adipocytes (32) and thereby increase the percentage of smaller adipocytes (7, 32). We found that PGZ alone increased mean adipocyte size in subcutaneous inguinal WAT compared with Veh, but this was not observed in epididymal WAT. Whether PPARγ agonists decrease or increase absolute FM appears to depend on the model studied and the metabolic conditions and possibly the source of WAT. PGZ has been reported to increase total FM (by 26%, measured by MRI) in obese Zucker rats (7) but decrease abdominal FM (by 10%, measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) in patients with type 2 diabetes (1). Furthermore, the PPARγ agonist troglitazone decreased epididymal fat pad weights in lean Zucker rats (by 15%; wet tissue) but increased this parameter in obese Zucker rats (by 30%; wet tissue) (32). However, the interpretation of wet fat tissue weight is difficult based on the well-established increase in fluid content of epididymal WAT in response to PPARγ agonism. We found that PGZ alone reduced total FM in nondiabetic Sv129 mice. This mouse model is a nonobese model, which might have facilitated FM reduction in response to PGZ treatment. PPARγ agonists have been shown previously to elevate UCP1 expression in epididymal and inguinal subcutaneous WAT, and this has been linked to FM reduction in mice (34, 38). UCP1 is expressed mainly in classical BAT and defends against obesity and hypothermia by inducing thermogenesis at the expense of ATP (54). PGZ alone increased UCP1 gene expression in epididymal WAT eightfold compared with Veh, and thus our data are consistent with the notion that PGZ induces FM reduction in part by metabolic uncoupling and thermogensis in WAT.

In the present study, ALG alone had no apparent effect on FM. How then can ALG enhance the PGZ-induced FM reduction? There could be a small reduction in FM by ALG, independent of PGZ, that we missed to detect. Studies in obese mice reported that the DPP IV inhibitors ALG and sitagliptin can reduce visceral fat pad weights (by 15–20%) (8, 41) and total abdominal FM (by 25%; measured by MRI) (39), respectively. DPP IV inhibitors can modestly decrease mean adipocyte size and shift the adipocyte size distribution to smaller values (8, 41). We did not detect significant effects of ALG alone on adipocyte size in epididymal and subcutaneous inguinal WAT but found that ALG consistently lowered adipocyte size in WAT in the presence of PGZ, indicating synergistic effects of ALG and PGZ. Whereas PPARγ agonists have been reported to induce a shift of fat distribution from visceral to subcutaneous adipose tissue (25), we found that adding ALG to PGZ treatment did not change fat distribution but similarly lowered visceral and subcutaneous WAT.

Previous studies showed that mice lacking DPP IV were protected against high-fat diet-induced FM gain due to higher UCP1 expression in BAT and reduced food intake (5). The incretin GLP-1, which is inactivated by DPP IV and increased with DPP IV inhibition, activates the GLP-1R in the central nervous system, thereby increasing BAT thermogenesis via activating the sympathetic nervous system (23) and inhibiting food intake via stimulating satiety centers (49). In accord with the findings of these studies, we found that ALG lowered food intake and that pair feeding prevented the BW-lowering effect of ALG in the presence of PGZ. Plasma FFA levels are determined by food intake and the release of FFA from adipose tissue (20). FFA release from adipose tissue is well regulated to maintain plasma FFA concentration within normal limits (20); however, extreme food intake causes excess FFA release and higher plasma FFA concentration and increased adiposity (20). In accord with these observations, plasma FFA levels are positively associated with FM (19). We found that ALG lowered plasma FFA, consistent with a previous study in obese mice in which chronic inhibition of plasma DPP IV activity (by 90%) with FE 999011 for 19 days decreased plasma FFA (by 40%) as well as food intake (by 20%) (44). In patients with type 2 diabetes, ALG alone and together with PGZ produced similar significant reductions in total postprandial triglyceride responses as well as triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (10). Therefore, we propose that the DPP IV antagonist ALG lowered BW in PGZ-treated mice in part by lowering food intake and plasma FFA.

In the current study, adding ALG to PGZ treatment enhanced the abundance of islets of multilocular cells in inguinal subcutaneous WAT, reminiscent of previously reported brown fat-like “beige” cells in this tissue (54, 55). Beige or “brite” cells resemble white fat cells in that they have extremely low basal expression of UCP1, but like classical BAT they respond to cAMP stimulation with high respiration rates (54). Beige cells have a gene expression pattern distinct from either white or brown fat and express the gene Tmem26 (54), which encodes a 41.6-kDa transmembrane protein that is conserved throughout evolution but whose function remains unknown (48). PPARγ agonists have been proposed before to induce a white-to-brown/beige fat conversion preferentially in subcutaneous WAT (31, 40). Our studies did not find consistent effects of PGZ alone on TMEM26 expression in WAT, but we found that adding ALG to PGZ treatment increased the expression of brown fat-like beige cell marker TMEM26 in inguinal subcutaneous WAT. Previous studies indicated that depots of BAT in adult humans as well as children are composed of beige adipocytes, which also express TMEM26 (40, 54). In this regard, we found that PGZ + ALG also increased the expression of TMEM26 in interscapular BAT of adult mice compared with PGZ alone. Moreover, PGZ + ALG increased the expression of TMEM26 in both interscapular BAT and inguinal subcutaneous WAT above the levels observed in VEH, whereas PGZ and ALG alone were ineffective. These changes also occurred when we controlled food intake by pair feeding and were associated with an increase in rectal temperature in PGZ + ALG vs. Veh, whereas PGZ and ALG alone did not affect rectal temperature. Thus, integrated changes in the TMEM26 expression in inguinal subcutaneous WAT and interscapular BAT paralleled the changes in rectal temperature. This is consistent with the notion that DPP IV inhibition by ALG may have lowered FM in PGZ-treated mice in part by synergistic effects of ALG and PGZ on thermogenesis in beige/brown fat cells. This food intake-independent increase in thermogenesis/browning of inguinal subcutaneous WAT and interscapular BAT should, in the context of equal food and energy intake, result in reduced BW. The finding that application of ALG to PGZ-treated mice did not lower total BW in the pair-feeding studies indicates that energy balance and BW regulation are more complex. Further studies are needed to carefully analyze energy expenditure and organ mass and better define the molecular nature of the synergistic interaction of DPP IV inhibitors and PPARγ agonists on the level of the adipocytes.

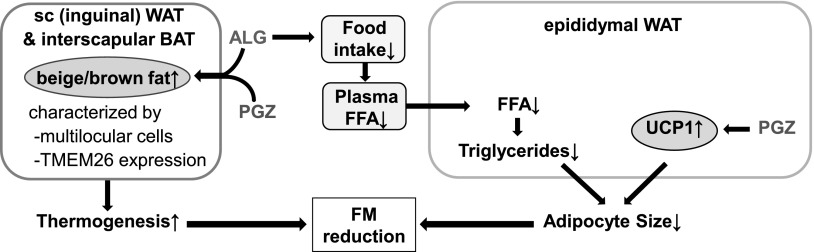

In summary, DPP IV inhibition did not attenuate PPARγ agonist-induced fluid retention but prevented BW gain by reducing FM. This involved ALG inhibition of food intake and was associated with food intake-independent synergistic effects of PPARγ agonism and DPP IV inhibition on beige/brown fat cells and thermogenesis (Fig. 9). An increase in FM is a crucial risk factor for the progression of cardiovascular disease and metabolic dysfunction (16, 52). Furthermore, an increase in the number of beige cells in WAT has been associated with protection against diet-induced obesity and metabolic diseases (35, 55). Therefore, we propose that combination treatment with a DPP IV inhibitor and a PPARγ agonist is a potent approach to lower FM and affect fat cell phenotype and deserves further experimental and clinical evaluation.

Fig. 9.

Proposed mechanism for synergistic effects of ALG and PGZ on FM. ALG decreases food intake and plasma FFA, which together with PGZ-induced UCP1 in epididymal fat lower the size of epididymal WAT and FM. ALG and PGZ act together to enhance TMEM26 expression and beige/brown fat cells in inguinal sc WAT and interscapular BAT, which are expected to enhance thermogenesis and lower FM.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants provided by the National Institutes of Health (DK-56248, HL-094728, and P30-DK-079337 to V. Vallon), the American Heart Association (Grant in Aid 10GRNT3440038 to V. Vallon), the Department of Veterans Affairs, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA (to V. Vallon). T. Masuda was supported by a fellowship of the Manpei Suzuki Diabetes Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

V. Vallon has received research grant support for basic science studies from Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA within the past 12 months.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.M., Y.F., and V.V. contributed to the conception and design of the research; T.M., Y.F., A.E., J.C., M.A.R., A.K., M.G., and V.V. performed the experiments; T.M., Y.F., M.S., and V.V. analyzed the data; T.M., Y.F., A.E., J.C., M.A.R., M.G., and V.V. interpreted the results of the experiments; T.M., Y.F., and V.V. prepared the figures; T.M. and V.V. drafted the manuscript; T.M., Y.F., A.E., J.C., M.A.R., A.K., M.G., A.E.F., M.S., and V.V. edited and revised the manuscript; T.M., Y.F., A.E., J.C., M.A.R., A.K., M.G., A.E.F., M.S., and V.V. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Bussell (University of California San Diego Center for Functional MRI) for technical support of MRI and Joanna Thomas (Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System) for critical suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basu A, Jensen MD, McCann F, Mukhopadhyay D, Joyner MJ, Rizza RA. Effects of pioglitazone versus glipizide on body fat distribution, body water content, and hemodynamics in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29: 510–514, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boerrigter G, Costello-Boerrigter LC, Harty GJ, Lapp H, Burnett JC., Jr Des-serine-proline brain natriuretic peptide 3–32 in cardiorenal regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R897–R901, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cariou B, Charbonnel B, Staels B. Thiazolidinediones and PPARgamma agonists: time for a reassessment. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23: 205–215, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman ME, Hu L, Plato CF, Kohan DE. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for the estimation of body fluid volumes in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F280–F283, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conarello SL, Li Z, Ronan J, Roy RS, Zhu L, Jiang G, Liu F, Woods J, Zycband E, Moller DE, Thornberry NA, Zhang BB. Mice lacking dipeptidyl peptidase IV are protected against obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6825–6830, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crajoinas RO, Oricchio FT, Pessoa TD, Pacheco BP, Lessa LM, Malnic G, Girardi AC. Mechanisms mediating the diuretic and natriuretic actions of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F355–F363, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Souza CJ, Eckhardt M, Gagen K, Dong M, Chen W, Laurent D, Burkey BF. Effects of pioglitazone on adipose tissue remodeling within the setting of obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 50: 1863–1871, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobrian AD, Ma Q, Lindsay JW, Leone KA, Ma K, Coben J, Galkina EV, Nadler JL. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor sitagliptin reduces local inflammation in adipose tissue and in pancreatic islets of obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300: E410–E421, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 368: 1696–1705, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliasson B, Möller-Goede D, Eeg-Olofsson K, Wilson C, Cederholm J, Fleck P, Diamant M, Taskinen MR, Smith U. Lowering of postprandial lipids in individuals with type 2 diabetes treated with alogliptin and/or pioglitazone: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia 55: 915–925, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang S, Suh JM, Atkins AR, Hong SH, Leblanc M, Nofsinger RR, Yu RT, Downes M, Evans RM. Corepressor SMRT promotes oxidative phosphorylation in adipose tissue and protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 3412–3417, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Festuccia WT, Blanchard PG, Turcotte V, Laplante M, Sariahmetoglu M, Brindley DN, Richard D, Deshaies Y. The PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone enhances rat brown adipose tissue lipogenesis from glucose without altering glucose uptake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1327–R1335, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girardi AC, Fukuda LE, Rossoni LV, Malnic G, Rebouças NA. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition downregulates Na+-H+ exchanger NHE3 in rat renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F414–F422, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girardi AC, Knauf F, Demuth HU, Aronson PS. Role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in regulating activity of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 in proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1238–C1245, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan Y, Hao C, Cha DR, Rao R, Lu W, Kohan DE, Magnuson MA, Redha R, Zhang Y, Breyer MD. Thiazolidinediones expand body fluid volume through PPARgamma stimulation of ENaC-mediated renal salt absorption. Nat Med 11: 861–866, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsueh WA, Law R. The central role of fat and effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma on progression of insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 92: 3J–9J, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito A, Suganami T, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Takeya M, Kamei Y, Ogawa Y. Role of MAPK phosphatase-1 in the induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 during the course of adipocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 282: 25445–25452, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaffrin MY. Body composition determination by bioimpedance: an update. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 12: 482–486, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen MD, Haymond MW, Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Miles JM. Influence of body fat distribution on free fatty acid metabolism in obesity. J Clin Invest 83: 1168–1173, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koutsari C, Jensen MD. Thematic review series: patient-oriented research. Free fatty acid metabolism in human obesity. J Lipid Res 47: 1643–1650, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamers D, Famulla S, Wronkowitz N, Hartwig S, Lehr S, Ouwens DM, Eckardt K, Kaufman JM, Ryden M, Muller S, Hanisch FG, Ruige J, Arner P, Sell H, Eckel J. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a novel adipokine potentially linking obesity to the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 60: 1917–1925, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesniewski LA, Hosch SE, Neels JG, de Luca C, Pashmforoush M, Lumeng CN, Chiang SH, Scadeng M, Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Bone marrow-specific Cap gene deletion protects against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med 13: 455–462, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockie SH, Heppner KM, Chaudhary N, Chabenne JR, Morgan DA, Veyrat-Durebex C, Ananthakrishnan G, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Drucker DJ, DiMarchi R, Rahmouni K, Oldfield BJ, Tschöp MH, Perez-Tilve D. Direct control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by central nervous system glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling. Diabetes 61: 2753–2762, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowell BB. PPARgamma: an essential regulator of adipogenesis and modulator of fat cell function. Cell 99: 239–242, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyazaki Y, Mahankali A, Matsuda M, Mahankali S, Hardies J, Cusi K, Mandarino LJ, DeFronzo RA. Effect of pioglitazone on abdominal fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 2784–2791, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moritoh Y, Takeuchi K, Asakawa T, Kataoka O, Odaka H. The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor alogliptin in combination with pioglitazone improves glycemic control, lipid profiles, and increases pancreatic insulin content in ob/ob mice. Eur J Pharmacol 602: 448–454, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray JW, Thosani AJ, Wang P, Wolkoff AW. Heterogeneous accumulation of fluorescent bile acids in primary rat hepatocytes does not correlate with their homogenous expression of ntcp. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G60–G68, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Napolitano A, Miller SR, Murgatroyd PR, Coward WA, Wright A, Finer N, De Bruin TW, Bullmore ET, Nunez DJ. Validation of a quantitative magnetic resonance method for measuring human body composition. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16: 191–198, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, Fonseca V, Grundy SM, Horton ES, Le Winter M, Porte D, Semenkovich CF, Smith S, Young LH, Kahn R; American Heart Association; American Diabetes Association Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. October 7, 2003. Circulation 108: 2941–2948, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohashi K, Parker JL, Ouchi N, Higuchi A, Vita JA, Gokce N, Pedersen AA, Kalthoff C, Tullin S, Sams A, Summer R, Walsh K. Adiponectin promotes macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. J Biol Chem 285: 6153–6160, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohno H, Shinoda K, Spiegelman BM, Kajimura S. PPARgamma agonists induce a white-to-brown fat conversion through stabilization of PRDM16 protein. Cell Metab 15: 395–404, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okuno A, Tamemoto H, Tobe K, Ueki K, Mori Y, Iwamoto K, Umesono K, Akanuma Y, Fujiwara T, Horikoshi H, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T. Troglitazone increases the number of small adipocytes without the change of white adipose tissue mass in obese Zucker rats. J Clin Invest 101: 1354–1361, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pacheco BP, Crajoinas RO, Couto GK, Davel AP, Lessa LM, Rossoni LV, Girardi AC. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition attenuates blood pressure rising in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 29: 520–528, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem 285: 7153–7164, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian SW, Tang Y, Li X, Liu Y, Zhang YY, Huang HY, Xue RD, Yu HY, Guo L, Gao HD, Liu Y, Sun X, Li YM, Jia WP, Tang QQ. BMP4-mediated brown fat-like changes in white adipose tissue alter glucose and energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E798–E807, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rangwala SM, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25: 331–336, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rieg T, Gerasimova M, Murray F, Masuda T, Tang T, Rose M, Drucker DJ, Vallon V. Natriuretic effect by exendin-4, but not the DPP-4 inhibitor alogliptin, is mediated via the GLP-1 receptor and preserved in obese type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F963–F971, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sell H, Berger JP, Samson P, Castriota G, Lalonde J, Deshaies Y, Richard D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonism increases the capacity for sympathetically mediated thermogenesis in lean and ob/ob mice. Endocrinology 145: 3925–3934, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah Z, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Zhong J, Pineda C, Ying Z, Xu X, Lu B, Moffatt-Bruce S, Durairaj R, Sun Q, Mihai G, Maiseyeu A, Rajagopalan S. Long-term dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis and inflammation via effects on monocyte recruitment and chemotaxis. Circulation 124: 2338–2349, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharp LZ, Shinoda K, Ohno H, Scheel DW, Tomoda E, Ruiz L, Hu H, Wang L, Pavlova Z, Gilsanz V, Kajimura S. Human BAT possesses molecular signatures that resemble beige/brite cells. PLoS One 7: e49452, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shirakawa J, Fujii H, Ohnuma K, Sato K, Ito Y, Kaji M, Sakamoto E, Koganei M, Sasaki H, Nagashima Y, Amo K, Aoki K, Morimoto C, Takeda E, Terauchi Y. Diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation and liver steatosis are prevented by DPP-4 inhibition in diabetic mice. Diabetes 60: 1246–1257, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith D, Jr, Johnson M, Nagy T. Precision and accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy for determination of in vivo body composition in rats. Int J Body Compos Res 7: 21–26, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sotiropoulos KB, Clermont A, Yasuda Y, Rask-Madsen C, Mastumoto M, Takahashi J, Della Vecchia K, Kondo T, Aiello LP, King GL. Adipose-specific effect of rosiglitazone on vascular permeability and protein kinase C activation: novel mechanism for PPARgamma agonist's effects on edema and weight gain. FASEB J 20: 1203–1205, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sudre B, Broqua P, White RB, Ashworth D, Evans DM, Haigh R, Junien JL, Aubert ML. Chronic inhibition of circulating dipeptidyl peptidase IV by FE 999011 delays the occurrence of diabetes in male zucker diabetic fatty rats. Diabetes 51: 1461–1469, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki R, Tobe K, Aoyama M, Sakamoto K, Ohsugi M, Kamei N, Nemoto S, Inoue A, Ito Y, Uchida S, Hara K, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Kadowaki T. Expression of DGAT2 in white adipose tissue is regulated by central leptin action. J Biol Chem 280: 3331–3337, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda Y, Fujita Y, Honjo J, Yanagimachi T, Sakagami H, Takiyama Y, Makino Y, Abiko A, Kieffer TJ, Haneda M. Reduction of both beta cell death and alpha cell proliferation by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition in a streptozotocin-induced model of diabetes in mice. Diabetologia 55: 404–412, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem 77: 289–312, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Town L, McGlinn E, Davidson TL, Browne CM, Chawengsaksophak K, Koopman P, Richman JM, Wicking C. Tmem26 is dynamically expressed during palate and limb development but is not required for embryonic survival. PLoS One 6: e25228, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turton MD, O'Shea D, Gunn I, Beak SA, Edwards CM, Meeran K, Choi SJ, Taylor GM, Heath MM, Lambert PD, Wilding JP, Smith DM, Ghatei MA, Herbert J, Bloom SR. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 379: 69–72, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vallon V, Hummler E, Rieg T, Pochynyuk O, Bugaj V, Schroth J, Dechenes G, Rossier B, Cunard R, Stockand J. Thiazolidinedione-induced fluid retention is independent of collecting duct alphaENaC activity. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 721–729, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vallon V, Rose M, Gerasimova M, Satriano J, Platt KA, Koepsell H, Cunard R, Sharma K, Thomson SC, Rieg T. Knockout of Na-glucose transporter SGLT2 attenuates hyperglycemia and glomerular hyperfiltration but not kidney growth or injury in diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F156–F167, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Pelt RE, Evans EM, Schechtman KB, Ehsani AA, Kohrt WM. Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E1023–E1028, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Liu J, Zhang A, Cheng P, Zhang X, Lv S, Wu L, Yu J, Di W, Zha J, Kong X, Qi H, Zhong Y, Ding G. BVT.2733, a selective 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor, attenuates obesity and inflammation in diet-induced obese mice. PLoS One 7: e40056, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, Huang K, Tu H, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Hoeks J, Enerbäck S, Schrauwen P, Spiegelman BM. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 150: 366–376, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu J, Cohen P, Spiegelman BM. Adaptive thermogenesis in adipocytes: is beige the new brown? Genes Dev 27: 234–250, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yazbeck R, Howarth GS, Abbott CA. Dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitors, an emerging drug class for inflammatory disease? Trends Pharmacol Sci 30: 600–607, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]