Abstract

Purpose

Long-term childhood cancer survivors may be at increased risk for poor social outcomes as a result of their cancer treatment, as well as physical and psychological health problems. Yet, important challenges, namely social isolation, are not well understood. Moreover, survivors' perspectives of social isolation as well as the ways in which this might evolve through young adulthood have yet to be investigated. The purpose of this research was to describe the trajectories of social isolation experienced by adult survivors of a childhood cancer.

Methods

Data from 30 in-depth interviews with survivors (9 to 38 years after diagnosis, currently 22 to 43 years of age, 60 % women) were analyzed using qualitative, constant comparative methods.

Results

Experiences of social isolation evolved over time as survivors grew through childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. Eleven survivors never experienced social isolation after their cancer treatment, nor to the present day. Social isolation among 19 survivors followed one of three trajectories; (1) diminishing social isolation: it got somewhat better, (2) persistent social isolation: it never got better or (3) delayed social isolation: it hit me later on.

Conclusions

Knowledge of when social isolation begins and how it evolves over time for different survivors is an important consideration for the development of interventions that prevent or mitigate this challenge.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Assessing and addressing social outcomes, including isolation, might promote comprehensive long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors.

Keywords: Survivorship, Adolescent and young adult, Childhood cancer survivor, Qualitative, Psychosocial, Social isolation, Social outcomes

Introduction

More than 82 % of children diagnosed with cancer are now cured of their disease and become long-term survivors [1]. This growing population is at increased risk for physical and psychological health problems as they age, such as a second cancer, cardiac dysfunction, neurocognitive dysfunction and psychological distress [2]. A subset of these survivors also endures social challenges in areas such as educational achievement, employment and financial independence, friendships and social interactions, intimate relationships and marriage as they progress through young adulthood [3–6]. Although previous research offers insights into specific social outcomes, important social challenges, in particular social isolation, are not well understood. Moreover, long-term childhood cancer survivors' perspectives of social isolation have not been systematically studied, nor have the ways in which this might evolve as survivors move through young adulthood. The purpose of this research was to describe the trajectories of social isolation experienced by childhood cancer survivors in their young adult years.

Background

Social isolation is often conceptualized as a paucity of contact with others (social disconnectedness) and a perceived lack of social support, and feelings of loneliness and not belonging (perceived isolation) [7, 8]. Social relationships and networks, or the lack thereof, have consistently been associated with poor health status and survival outcomes among the general population, patients with chronic medical conditions, and adults with cancer [9–14]. Although some childhood cancer survivors report feelings of not fitting in, loneliness and social isolation [15], these complex experiences are not fully understood among this population. There is also limited knowledge of the potential changing nature of social isolation as survivors mature. In one study, children and adolescent cancer survivors reported differences in the importance of social relationships and that as they aged, peer relationships and support became increasingly important while the need for family support continued [16]. Overall, however, research has not examined how social isolation arises, evolves over time or influences long-term survivors' lives and future expectations.

Recent evidence suggests that most childhood cancer survivors do not experience psychosocial late effects, but a subset of survivors do endure social challenges that do not dissipate and might underlie further social difficulties during adulthood [2, 17–19]. Childhood central nervous system tumour survivors and those treated with cranial radiation are at risk for poor social functioning and adjustment [5, 20–28]. These survivors are also at risk for educational difficulties including repeating a grade in school, requiring special education or learning disabilities programs, not entering or completing post-secondary school and struggling with notions of incompetence in educational settings [3, 19, 29–35]. During adulthood, relationships with family and friends can be complicated by disruptions in psychological developmental, chronic medical conditions and delays in achieving autonomy from the nuclear family. Childhood cancer survivors report having fewer friends, difficulties forming close friendships and a lower likelihood of spending leisure time with friends [3, 36, 37]. Intimacy appears to be affected such that some survivors experience significant levels of sexual dysfunction, are older when they have their first boyfriend or girlfriend and sexual relationship, and they are less likely to marry compared to siblings and national averages [19, 36–42]. The evidence consistently demonstrates that brain tumour survivors and those who received cranial radiation are the most vulnerable to the above-mentioned social difficulties.

Young adulthood, in particular, is a stage of development involving many life-related changes, including decisions about education, employment, relationships and family that can be severely affected by the social late effects of cancer. The perspectives of cancer survivors who are currently in their young adult years have remained on the periphery of health and social services development and policy making [29, 43]. Yet, this evidence is crucial for understanding and meeting the needs of this unique population. This knowledge is also essential for developing relevant social supports and resources to prevent, as well as mitigate, social late effects like isolation. Addressing medical but also psychosocial challenges in adolescence and young adulthood is a key to bolstering the formative years that promote, or limit, lifetime potential.

Methods

This study was conducted in the context of a larger study examining the medical and psychosocial challenges and needs of long-term childhood cancer survivors.

Guiding theory

The collection and analysis of data were informed by the theory of relational autonomy [44, 45]. This theory has shaped previous investigations of patient decision making related to genetic testing [46], hereditary cancer risk-reduction [47], medical treatment for breast cancer [48], as well as family caregiving in oncology [49], truth-telling to cancer patients [50] and ethno-cultural disparities in older breast cancer patients [51]. In contrast to an individualistic, objective view of autonomy, relational autonomy highlights the interconnectedness and interdependence of individuals, and the dynamic balance among people who are closely involved in each others' lives [48]. A relational view of autonomy characterizes the individual as embedded in relational networks that include family, friends and health professionals, as well as institutional, political and social systems [44, 52]. These relational networks are accompanied by social obligations, including roles and responsibilities, which provide the framework within which individuals act [44]. Using a relational autonomy lens initially helped us formulate the specific research questions and interview guide to enable an exploration of survivors' experiences in the context of their interpersonal relationships. For example, we asked participants to describe their social life and any challenges they had experienced, as well as to reflect on how family, friends, health care professionals and organizations helped and/or hindered them in managing or coping with social challenges. While inductively coding the transcripts during data analysis, we noted when participants identified different individuals who made up their social networks. During data analysis, we also diagrammed survivors' social life and challenges paying particular attention to their descriptions of the different roles peers, friends, family members and co-workers played in their lives and how these changed over time.

Study participants

Cancer survivors who were diagnosed with cancer prior to 19 years of age were recruited through follow-up clinics in British Columbia, Canada. Study fliers were given to potential participants who attended a Post-Pediatric Late Effect Clinic at the adult cancer centre and a Long-Term Follow-Up Clinic at a children's hospital. Study notices were also posted in relevant online forums and websites. A convenience sample of 30 long-term childhood cancer survivors participated in this research. Participants ranged in age from 22 to 43 years (mean 31 years) at the time of interview and were 9 to 38 years (mean 22 years) from the time of diagnosis. See Table 1 for demographic information and Table 2 for disease characteristics and late effects. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Ethics approval was granted through the University of British Columbia.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information, by trajectory of social isolation

| Demographic characteristics | All, n = 30 (%) | Never isolated, n = 11 (%) | Diminished isolation, n = 9 (%) | Persistent isolation, n = 4 (%) | Delayed isolation, n = 6 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–24 | 16 | 9 | 33 | 25 | 0 |

| 25–29 | 27 | 36 | 0 | 25 | 50 | |

| 30–34 | 30 | 36 | 11 | 50 | 33 | |

| 35+ | 27 | 19 | 56 | 0 | 17 | |

| Gender | Male | 40 | 45 | 22 | 25 | 67 |

| Female | 60 | 55 | 78 | 75 | 33 | |

| Place of residency | Greater Vancouver area | 70 | 82 | 56 | 50 | 83 |

| Other | 30 | 18 | 44 | 50 | 17 | |

| Marital status | Single | 73 | 55 | 89 | 75 | 83 |

| Married | 27 | 45 | 11 | 25 | 17 | |

| Living arrangement | Alone | 30 | 27 | 33 | 25 | 33 |

| With roommates | 13 | 18 | 11 | 0 | 17 | |

| With a partner/spouse | 27 | 45 | 11 | 25 | 17 | |

| With parents | 30 | 9 | 44 | 50 | 33 | |

| Level of education | Did not complete high school | 7 | 9 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| Completed high school | 23 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 33 | |

| Completed university/college | 70 | 73 | 78 | 50 | 67 | |

| Employment status | Unemployed | 13 | 0 | 22 | 25 | 17 |

| Student | 10 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 33 | |

| Employed part- or full-time | 77 | 100 | 78 | 50 | 50 | |

Table 2.

Participant disease characteristics and late effects, by trajectory of social isolation

| Disease characteristics and late effects | All, n = 30 (%) | Never isolated, n = 11 (%) | Diminished isolation, n = 9 (%) | Persistent isolation, n = 4 (%) | Delayed isolation, n = 6 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first diagnosis | 0–4 | 27 | 18 | 45 | 0 | 33 |

| 5–9 | 33 | 18 | 33 | 50 | 50 | |

| 10+ | 40 | 64 | 22 | 50 | 17 | |

| Type of cancer | Leukemia or lymphoma | 53 | 55 | 56 | 25 | 67 |

| Brain tumor | 20 | 0 | 22 | 75 | 17 | |

| Sarcoma (not including brain) | 20 | 27 | 22 | 0 | 17 | |

| Other solid tumours | 7 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Treatments | Radiation therapy | 90 | 82 | 89 | 100 | 100 |

| Chemotherapy | 97 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 100 | |

| Surgery | 37 | 27 | 22 | 75 | 50 | |

| Bone marrow transplant | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Late effects and health problems | Second cancer | 30 | 9 | 22 | 50 | 17 |

| Learning difficulties or cognitive impairment | 30 | 9 | 44 | 50 | 33 | |

| Impaired growth and development | 43 | 0 | 44 | 100 | 17 | |

| Bone, joint, or soft tissue late effects | 40 | 27 | 56 | 75 | 33 | |

| Visual impairment | 23 | 18 | 78 | 50 | 17 | |

| Hearing impairment | 27 | 9 | 44 | 25 | 17 | |

| Impaired sexual development or infertility | 30 | 0 | 33 | 50 | 50 | |

| Cardiovascular late effects | 17 | 36 | 22 | 25 | 33 | |

| Respiratory late effects | 17 | 27 | 22 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dental late effects | 13 | 27 | 22 | 0 | 0 | |

| Endocrine late effects | 30 | 18 | 11 | 25 | 0 | |

| Digestive late effects | 20 | 18 | 56 | 50 | 0 | |

| Anxiety or depression | 37 | 0 | 44 | 100 | 50 | |

Data collection procedures

One investigator (FH) conducted 30 in-depth interviews lasting 45 to 120 min. Twenty of the interviews were conducted in person, while ten were done over the phone due to participant's availability and/or living outside of the city centre. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. An interview guide was used to ensure common themes and topics were explored across interviews, and questions were open-ended to obtain participants' perspectives about their experiences. The interview questions were designed to draw out the medical and psychosocial challenges and needs of survivors, which also captured details about social life and challenges. For example, we asked the survivors to describe their perspectives of: the medical, emotional and social challenges they experienced; how they managed and coped with these challenges; who or what (including peers, friends, family, health care professionals, institutions and organizations) helped and/or hindered their managing and coping with these challenges; how medical and emotional challenges affected their social life and/or relationships; how the way they manage their medical, emotional and social challenges has changed over time (from when they finished cancer treatment until the present); and how their health and well-being has changed over time (from when they finished cancer treatment until the present). As analysis of early interviews proceeded, questions became more specific in subsequent interviews to fill in gaps and explore in more detail important ideas that arose in preceding interviews and preliminary analysis. For example, participants in the initial interviews discussed the importance of peer relationships and how friendships and their social life had changed as they matured. Therefore, participants in subsequent interviews were asked to describe their friendships and social life when they were younger and at the present time, and to reflect on the differences.

Data analysis procedures

Interview data was analyzed using thematic analysis and constant comparative methods. Interview transcripts were read several times and coded by one investigator (JTDB) for important concepts, events, interpretations and experiences relevant to the research questions of the larger study, using an inductive approach [53]. The data was coded using NVivo 10TM, a qualitative software program. One of the broad themes arising from this inductive coding was social life and challenges with peers, friends, partners and family. Three investigators (AFH, JTDB and KS) then developed and reviewed constructed narratives for each participant that summarized their cancer history, medical and psychosocial challenges, significant events and experiences related to these challenges, and the role that individuals (including peers, friends, partners and family) and organization had played. All transcript data in the broad social life and challenges theme was then retrieved, as was the section of the constructed narratives that summarized the participant's social life and challenges and the role of different individuals (including peers, friends, partners and family) in their past and current life. This data was reviewed by two investigators (AFH and JTDB) to identify important themes that recurred within the interviews and were evident in multiple participants' accounts, again using an inductive approach. At this point, social isolation was identified as a main theme, with varying degrees of severity represented across participants.

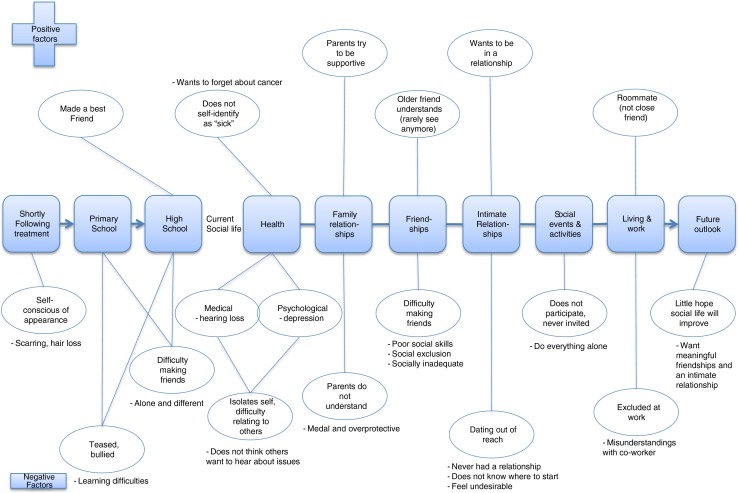

Three of the investigators (AFH, JTDB and KS) then diagrammed each participant's constructed narrative as it related to their social life and challenges, allowing for the investigators to group participants according to similarities and differences in experiences of social isolation [54]. These linear diagrams depicted change over time by beginning with early social experiences, such as those during childhood and elementary school, and progressing through to current social life. These diagrams listed the salient factors and experiences that participants perceived shaped their social life, such as type and quality of peer, friend, family and intimate relationships, participation in specific social events/activities/camps, past and present living and work arrangements, and medical and emotional challenges. These diagrams included details about these factors and experiences specific to the participant, and the ways in which the participant coped with formative experiences. These salient factors and experiences were qualified as positive or negative and either contributing to or easing social isolation, with all positive elements placed on the top half of the diagram and negative elements placed on the bottom of the diagram. Rather than provide an example of one of the study participant diagrams, which contains detailed, personal and identifying information, Fig. 1 depicts a generic composite diagram without quotes or participant specific examples. These diagrams were discussed at great length and four predominant trajectories of social isolation were identified. Three of the investigators (AFH, JTDB and KS) then compared and contrasted these four groups [54, 55], focusing on the evolution of participants' experiences, the antecedents and consequences of social isolation, coping mechanism when social isolation occurred, and talk of the future. This process continued until all ideas, interpretations and trajectories were accounted for in the final description, which was then refined by all investigators for clarity.

Fig. 1.

Generic composite diagram of social life and challenges constructed narrative

Results

Experiences of social isolation evolved over time as the survivors grew through childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. Eleven survivors never experienced social isolation following their cancer treatment, nor to the present day. Social isolation among 19 survivors followed one of three trajectories; (1) diminishing social isolation: it got somewhat better, (2) persistent social isolation: it never got better or (3) delayed social isolation: it hit me later on. Table 1 displays the participant's demographic characteristics according to the four main trajectories, while Table 2 displays their disease characteristics and late effects by trajectory. These trajectories shared some similarities but also differed in key life events, stages and dimensions of the survivors' lives, such as school experiences, parental support, strategies for coping with difficulties and future outlook, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key events and components of social isolation trajectories

| Key events | Never isolated, n = 11 | Diminished isolation, n = 9 | Persistent isolation, n = 4 | Delayed isolation, n = 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return to school | Easily reintegrated | Experienced severe social isolation and bullying | Experienced social isolation and bullying | Have friends and “normal” school life |

| Family support | Supportive, encouraging | Supportive, close | Mixed | Supportive, positive |

| Peer or professional support | Some peer support accessed when younger, but not needed later on | Some peer and professional support accessed when younger | Some peer and professional support accessed, but not beneficial | Some peer and professional support accessed, but not beneficial |

| Ways of coping | Control over cancer identity | Finishing high school, partying | Self-isolating strategies | Anxiety about socialization |

| Current social life | Strong social network | Fulfilling social life | Social isolation persists, social functioning is difficult | Progressive social isolation and left behind by peers |

| Education and employment | Successful | Successful | Delayed, struggling | Delayed, struggling |

| Intimacy and dating | No difficulties | Limited, feel that peers are passing them by | Out of reach | Out of reach |

| Late effects | Have not interfered with social ability or outlook | Have not interfered with social ability or outlook | Have interfered with social ability, daily life and outlook | Have interfered with social ability, daily life and outlook |

| Depression | Did not experience depression | Struggled intermittently with depression | Depression and loneliness are pervasive | Depression and loneliness as young adults |

| Cancer survivor identity | Cancer is in the past | Cancer is in the past | Did not elaborate | Cancer is still part of current life and identity |

| Future outlook | Positive | Optimistic | Powerless | Uncertain |

No social isolation

Eleven of the cancer survivors in this study never experienced social isolation.

No social isolation after treatment

After completing treatment, these survivors returned to elementary or high school without significant physical or cognitive impairments and they continued with social activities, sports and “regular life things,” which enabled them to maintain their friendships. They were not bullied or socially excluded, and many had friends who stuck with them throughout their cancer treatment.

I had taken that entire time off of school, so as an adolescent I was relieved that I could get back into it and get back into the social aspects of life and play sports again and all of that. So I was very focused on things getting back to normal… [I] didn’t feel like I was ostracized at all at school. I felt like I had a lot of support from my peers and, it wasn’t a difficult reintegration at all. [Lymphoma survivor]

These survivors commonly described the supportive relationships they had with their parents and siblings as essential in assisting them to build self-confidence and encouraging their participation in activities that would “get me into the social environment” after completion of their cancer treatment. A few of these survivors attended a camp for children diagnosed with cancer when they were younger, and at that time, benefited from friendships with other survivors.

Current social life

These survivors currently have fulfilling social lives, close relationships with old and new friends, and friends from a variety of networks, such as work, school and sports teams. They continue to draw on the positive support of friends and family.

I have such an amazing group of friends and family that if I ever worry about it [cancer recurrence] or if I ever get sent for way more tests than the regular, then maybe I get a little bit more worried and speak with my family and friends but I think my family is quite unique and very supportive and maybe other people don’t have that… So I’m grateful for them. And I think if I didn’t have them I probably would seek out help. [Nephroblastoma survivor]

These survivors are comfortable meeting new people and engaging in social activities, because they have the skills to control how they present themselves and how others perceive them. Even though many of these individuals have visible physical signs of having had cancer, such as a scar, short stature or facial hypoplasia, they do not associate their physical appearance with any social challenges. These survivors developed strategies for incorporating or not incorporating information about their cancer history into social relationships. Some are open about disclosing their cancer history, while others wait before sharing this component of their life.

When I meet people for the first time I don’t bother mentioning it [cancer history] because I feel like there’s no point because I make people uncomfortable… If they notice something different [appearance] then usually I just make up something. But if I actually get to know them and I feel like we’re becoming actual good friends then I might casually mention it and usually it just goes off really easily. And I always close [with] something like, if you have any questions or if you want to talk about things I’m really open to it. I think at that point in our relationship because we both know that we’re becoming friends it becomes way easier to talk about. [Sarcoma survivor]

These same skills were useful in dating and intimate relationships. These survivors did not have challenges with physical or emotional intimacy related to having had cancer; half are married, and the others are currently in a relationship or dated in the past.

Future expectations

Moving on and past cancer was relatively uncomplicated for these survivors, and therefore, they did not have the need for professional or peer support. They are aware of their health risks, but this does not factor into their relationships or participation in social activities. Their thoughts for the future are not defined by having had cancer, and most have a positive outlook.

Diminishing social isolation: it got somewhat better

Nine of the cancer survivors experienced social isolation after completing their cancer treatment during their pre-adolescent and adolescent years, but this improved somewhat after graduating from secondary school.

Social isolation after treatment

These survivors recalled spending significant time in the hospital during treatment where they felt surrounded by adults, had few friends to confide in and missed out on social activities and learning how to socialize with others their age. Beginning school afterwards was a negative and scary experience, particularly for those who were self-conscious about their appearance after having lost their hair, having impaired eyesight or hearing, or having gained weight. Difficulty making friends and extreme bullying at school exacerbated feelings of social isolation. School was overwhelming not only because of difficulties keeping up with the schoolwork but also because of the survivor's desire to fit in socially.

You’re trying to make friends, you’re trying to deal with the fact that so and so is playing with so and so and you’re not invited… then at the same time you’re not getting your math and your spelling is horrible and it takes you three times longer to read anything than anyone else and it just feels like everything is piling up on you. [Leukemia survivor]

The diagnosis of a learning disability, likely related to cancer treatment, was a side effect that not only physically isolated these survivors but also contributed to their feeling different from peers. These survivors had teaching assistants, attended extra classes for assistance when other students were participating in extracurricular activities, and sat in a separate room to accommodate special needs equipment. Social anxiety and depression intensified during high school when their desire to “fit in” became even more important.

Because of all the weight I gained on my medication and through the chemo like all the prednisone and stuff, it was very hard for me to lose the weight. So it was the opposite. It wasn’t wanting everyone in your class to understand what you were going through, like when I was in my elementary… You want to be just like everyone else. [Leukemia survivor]

To cope, nearly all of these survivors accessed formalized psychosocial support as an adolescent from a psychologist or a cancer-specific support group. While some found comfort and support in talking with other survivors, others did not benefit from this experience.

Current social life

Social isolation diminished after high school such that these survivors currently have fulfilling social lives relative to their adolescent years. They have meaningful relationships with at least a few friends with whom they enjoy spending time. The close relationship these survivors had with their parents and siblings when they were younger continued through young adulthood, with many survivors citing them as good friends and confidants.

While feelings of social isolation waned overall, social difficulties lingered for some. A few felt abandoned when their parents offered less social support, or, in contrast, felt smothered when their parents constantly meddled in their social life. Four of these survivors struggled intermittently with depression, feeling lonely or different, and some coped by isolating themselves. Others turned to alcohol, illicit drugs and partying to help them forget about their problems, build self-confidence and overcome feeling shy.

I have kind of a life with my friends and I kind of go out and do things and party. Partying is not good but it’s a factor for me because I have to let it out . . . I feel better about myself and I feel better that I’ve let myself go and let all that frustration out. Like when you’re drinking you’re not really aware of the real world, what’s going on? [Leukemia survivor]

Most had limited experience with dating or romantic relationships, and felt that their peers were passing them by in terms of marriage and having children. A number of the survivors now felt ready to meet a life partner.

I’ve never really had a serious relationship but, that’s something I would definitely want, maybe marriage… In the past it would have been disastrous, I think probably nothing would have lasted because I was looking for another to complete who I was. But now I only would want to have a relationship with somebody if I know who I am. [Leukemia survivor]

Future expectations

These survivors focused on putting cancer in the past and were optimistic about their future, wanting to be happy, healthy and have a family. They did not want peer support now because they wanted to “forget about cancer,” they did not want to identify as “sick” and or were “tired of complaining about problem” [Lymphoma survivor]. Even those who continue to be plagued by health issues, such as early menopause or a cancer recurrence, had a positive outlook, expecting that their health and social well-being was “only going to get better” [Lymphoma cancer survivor].

Persistent social isolation: it never got better

Four of the survivors in this study experienced persistent social isolation that began at a young age and never improved. Three of the four were survivors of a brain tumour.

Social isolation after treatment

These survivors experienced social isolation and were bullied by their peers prior to or beginning at the time of their cancer diagnosis. Feeling alone, shy, withdrawn, different, less than their peers and socially inadequate shaped the development of their self-concept.

I’d been bullied a bit and neglected by my peers somewhat up until my diagnosis and any friend that I had at the time [of diagnosis] sort of disappeared…. The neglect kind of continued because I was different. I was phenomenally [different], I was this reminder that we’re not, you know, immune to death. [Leukemia survivor]

They perceived that their social development was interrupted, impairing their capacity to function in social situations and connect with others.

My social development was sort of interrupted too because I was diagnosed right at that age where you’re starting to kind of find yourself in a way? … So I missed out on a lot of that social development so I was kind of behind everybody else in that sense too and I don’t think I’ve ever really been able to pick that up. [Leukemia survivor]

While in school, these survivors also suffered from cognitive impairments and learning disabilities, for which they were ridiculed, further exacerbating feelings of being different and affecting their ability to succeed scholastically. Despite assistance from teachers and their parents, school was difficult for these survivors. The three survivors who attended peer mental health, cancer support groups or retreats as adolescents derived little benefit because they did not relate to others nor did they form lasting friendships.

Current social life

Marked social isolation continued throughout young adulthood for these survivors. They carry the hurt of being excluded and bullied and still self-identify as different and socially inadequate. These survivors perceived that their impaired social functioning coupled with continued social exclusion made forming new relationships difficult. While one survivor receives tremendous social support from family members, the others had troubled relationships with parents or siblings that have not improved. Even though three of these survivors were either working or in school part time, they felt excluded and “not part of the group.” They also described not having meaningful relationships or enjoying social interactions.

[I] lack [the] ability to have fun even now… Maybe if I had more of a circle of friends then I would have more opportunity but I haven’t really discovered ways that I feel good about myself… Or have fun or just like let go, I always worry about what people think. [Brain tumor survivor]

As young adults, these survivors became frustrated when others did not understand or accommodate their special needs. For example, one survivor who struggled with cognitive impairment, hearing loss and anger management recounted multiple instances of misunderstandings and conflicts with co-workers, employers, acquaintances and even strangers. Dating and intimacy were perceived to be out of reach by all but one individual who was married.

Depression and loneliness were pervasive themes in these survivors' lives, which some attributed to anxiety about their health, individual events, such as loss of employment or a relationship break-up, or low self-esteem.

I have a really strong voice in my head that’s always either putting me down or, you know, criticizing… The other day I tried to come up with times when I felt good about myself, and I couldn’t really think of any. [Brain tumor survivor]

Two survivors took comfort in their faith or having pets, while another coped by using alcohol, illicit drugs, harming himself and gaming. However, some of these coping strategies may perpetuate depression and social isolation.

Future expectations

These survivors desperately wanted a more fulfilling social life.

Honestly, I’d pretty much do anything, somebody would have to, would have to like invite me but I’m, I like hiking, I like all the outdoor things, I’m willing to go out to whatever and I’m willing to do anything, but I know no-one invites me out anywhere. [Brain tumor survivor]

These survivors were consumed with their current life challenges, seemed to feel powerless in changing their social situation, lacked hope about their future and described waiting for someone or something to change.

Delayed social isolation: it hit me later on

Six of the survivors in this study experienced unexpected, delayed and progressive social isolation that began in young adulthood.

Social isolation after treatment

These survivors formed close friendships and for the most part, had “normal” social interactions during elementary and high school.

Current social life

As these survivors grew into young adults, they were surprised when they began to feel socially isolated.

I had a few close friends [in university] but not so much anymore. And one of my friends said something to me he was really close to me and he said, “I used to like you more back in like early university days,” because I was the life of the party and I was the happy go lucky guy and I’ve slowly lost that. [Leukemia survivor]

These survivors feel “stuck” and are struggling to move on to the next phase of their life. They encountered difficulties reaching milestones common in young adulthood, such as finishing post-secondary school, establishing, succeeding or progressing in one's career, forming an intimate relationship and having children. These survivors witnessed their peers pass them by in reaching these milestones, which they equated with happiness and a “normal life.” Over time, their social interactions diminished because friends were increasingly occupied with work and family commitments, while they were not. The survivors felt socially “left behind,” their life path diverged from those of their peers, and they could not relate to others.

The late effects of cancer treatment, including neurocognitive disability, facial hypoplasia, hearing loss, headaches, fatigue and chronic infections, limited these survivor's willingness and ability to engage in social activities.

I don’t have a lot of energy for a large group of friends or to go out. And I find going out with a large group, I mean I do get drained really fast. But, oh, another side effect I have is when I’m talking to somebody and there’s other sounds around or other conversations I can’t block that out. I still hear that, it’s regular level. I know when most people are talking they’re able to focus on that specific conversation, so it takes a lot of energy and effort for me to focus specifically on one conversation. [Brain tumor survivor]

Also limiting their perceived ability to socialize were the survivors' fears of being disliked, low self-confidence and low self-esteem. Group interactions were particularly intimidating because of anxiety about talking to others and performing socially. These survivors also struggled to relate to others because they felt more mature.

I find it very difficult to socialize with people around my age group because I’ve had a lifetime worth of experiences. So I feel I’m at a different stage in my, I don’t even know how to say it. I’ve gained a lot more wisdom than most people, so I find it difficult to relate to people who are still concerned and worried about all the superficial stupid stuff that doesn’t matter. [Brain tumor survivor]

Intimate relationships, and the lack thereof, were perceived to be out of reach for four of these survivors because they had never had a boyfriend or girlfriend and had trouble meeting a potential partner.

I’ve never had a boyfriend before, I’ve never kissed or whatever. And so it’s frustrating because, you know, my friends are growing up, moving on with their lives”. [Leukemia survivor]

These survivors did not trust potential partners easily and worried that medical issues, such as infertility or a second cancer, would interfere with a romantic relationship.

Five of these survivors experienced depression as young adults, when emotional and social challenges intensified. Although some received effective professional support, appropriate forums for peer support that consisted of social activities and networking with other cancer survivors were not available.

Future expectations

These survivors perceived their future as uncertain because of current or potential medical issues, such as a cancer recurrence. They were losing hope that their life would not turn out the way they had expected regarding their career, a relationship and having children, further distancing them from peers.

I try not to think too far ahead. I’m at the point where I don’t think I’ll be going back to work. It’s hard because all my friends are working and starting families and I don’t see that in my future anymore. It is tough because I think all, all little girls think of that in their future. Well I try not to think about it too often. [Leukemia survivor]

Discussion

Even though social isolation was a significant issue that many of the childhood cancer survivors struggled with at some point following cancer treatment, it is noteworthy that this never appeared to be an issue for other survivors. The feeling of social isolation was not a static aspect of the survivors' lives, but rather, evolved over time. Social isolation eased for some of the survivors as they left childhood and adolescence behind, yet this was unrelenting and continues to the present-day for others. There were also survivors who experienced unexpected and delayed social isolation that began in young adulthood.

Research to date indicates that brain tumour survivors and those treated with cranial radiation are at highest risk for poor social outcomes [3, 19, 56]. Although survivors in our study who experienced unrelenting social isolation included brain tumour survivors, it was not only brain tumour survivors who described social difficulties. Moreover, there were brain tumour survivors who felt their social circumstances improved in young adulthood. It is possible that physical, psychological and social late effects contribute to a cascade of additional social difficulties and that social isolation is one result of the culmination of life challenges. In this study, survivors who experienced social isolation also discussed medical (i.e., facial hypoplasia, impaired hearing and vision, fatigue and headaches) and psychological (i.e., anxiety, depression and fear of cancer recurrence) issues; however, the relationship between these late effects and social isolation remains unknown. Future research that identifies and examines the ways in which various factors, such as patient characteristics, treatments, and medical, psychological and social factors, contribute to social isolation would have theoretical utility and might also help identify those survivors at highest risk for social isolation. Our results also suggest value for future studies of childhood cancer survivors to include measures of perceived social relationships, social networks and social support and to further characterize the trajectories of social isolation identified in our study, as well as potential additional trajectories. This knowledge, as well as a comprehensive understanding of the implication of social isolation, would advance theoretical understandings of this concept.

The survivors in this study connected their current social functioning and circumstances with early positive and negative experiences, most often school related. Reintegrating into social activities and returning to normal routines assisted survivors in perceiving themselves as socially competent at a young age and, seemingly, in adulthood. In contrast, the school environment did not effectively foster social integration for others. Survivors who recounted painful and vivid memories of not fitting in, feeling different, and being excluded, picked on or bullied described carrying these traumatic social experiences with them as they aged, even among those who felt their social circumstances improved somewhat in young adulthood. This finding is in line with those of van Dijk and colleagues, who reported that bullying in childhood and the subjective experience of impairment are the main predictors of poor social functioning and overall quality of life among retinoblastoma survivors [57]. Even though social experiences during the formative childhood and adolescent years were significant in the survivors' narrations of their present social life, future investigations into how these experiences influence social outcomes in adulthood are warranted.

It is possible that these early experiences influenced the survivor's self-esteem and self-confidence, which some indicated influenced their ability to engage in social activities and build requisite social skills. This provides insight into reports that self-esteem is positively related and may serve as a protective factor for educational and social outcomes for childhood cancer survivors less than 17 years of age [3]. Yet, it remains unknown whether low self-esteem predisposes an individual to early traumatic social experiences, or whether negative early social experiences result in low self-esteem. It is likely a bit of both. Our finding that socially isolated survivors reported low self-esteem or self-confidence and appeared to suffer disproportionately from depression aligns with previous research wherein social skills and self-worth played important roles in depressive symptoms among brain tumour survivors (<18 years of age) [58] and lower levels of self-esteem were associated with lower quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer [59]. The participants in our study who experienced delayed social isolation attribute this, in-part, to functional late effects, such as hearing loss, and low self-esteem. This adds to research suggesting that health/functional status, psychological self-perception (body image and physical self-confidence) and related social anxiety can worsen with age [60, 61].

This study provides evidence that social isolation can develop among young adult survivors who previously had full and meaningful social lives and that not fitting in and reaching milestones common in young adulthood (career, marriage, children) are contributing factors. The importance of peer acceptance and support during adolescence is well recognized, but it also appears that childhood cancer survivors continue to compare themselves to their peers well into their young adult years [29, 62]. This highlights the significance of socially constructed ideas of what constitutes a happy and fulfilling life and that survivors compare themselves with mainstream ideas and messages of normal and different. It is unknown whether psychosocial support or interventions could assist these survivors to cope with unexpected social challenges before or when they arise during adulthood, and thus, research in this area is needed.

In this study, survivors who experienced social isolation had limited structural social support, that is, smaller and less integrated social networks that could assist them to cope with demands and achieve goals [8]. Details of parental social support were less prominent in descriptions provided by survivors who considered themselves socially isolated. In a review, Decker concluded that adolescent cancer survivors report adequate levels of support from parents and that they value this support [8]. It is possible that the degree and nature of social support previously provided by parents in this study changed as children matured into adults, a change some survivors possibly struggled with, contributing to feelings of social isolation. It is also possible that the quality and nature of the parent–child relationship as well as parent–child attachment style could play an influential role in survivors' ability to re-engage in social activities following cancer treatment and into adulthood. There is evidence that childhood cancer survivors' perceptions of their relationships with their parents are linked to their current psychosocial adjustment and well-being [63–65]. Orbuch et al. [64] found long-term childhood cancer survivors' reports of more positive father–child relations were associated with social and psychological well-being, while more positive mother–child relations were associated with psychological well-being. Hill et al. [65] found that among young adult survivors of childhood Wilms and leukemia, lack of parental encouragement, higher maternal involvement, lower paternal influence and discord with mothers were associated with poor adult relationships. Research is needed that further explores the effects of the parent–child relationship when children mature into adulthood, particularly in situations where survivors struggle with independent living and continue to experience health challenges.

Forming friendships is a critical developmental task that promotes social competence, psychosocial adjustment and mental health. Moreover, social relationships and networks, or the lack thereof, are associated with cancer mortality [14]. Our findings enrich our understanding of previous evidence suggesting that friendship, marriage, parenthood and sexuality can be areas of concern for survivors, particularly those diagnosed with a central nervous system tumour or leukemia [19]. However, it is unknown how social isolation and social life continues to evolve for survivors throughout the life course and research with middle and older age adults is appropriate. Moreover, research is sorely needed that investigates the long-term effects of social isolation on childhood cancer survivors' risks for chronic disease, late effects (including a second malignancy) and mortality.

The adult survivors who were socially isolated in our research had a deep desire for full and meaningful relationships but were unable to access effective assistance or support, pointing to the need for accessible interventions. Carefully crafted school reintegration interventions that partner with school staff, promote peer acceptance and take into account the school environment will likely ease the post-treatment transition to regular school life [66, 67]. The development of interventional strategies that prevent or mitigate early social challenges, especially teasing, bullying and social exclusion, during the formative childhood and adolescent years might also promote initial, but also long-term, social functioning. Moreover, family-based interventions that take into account the parent—child relationship might be particularly beneficial [67, 68]. Multifaceted interventions that assist individuals to cope with medical and psychological late effects that can contribute to social isolation are likely to be more effective, as are interventions that build on survivors' strengths and bolster self-esteem and self-confidence. Our research suggests that while many childhood cancer survivors are resilient, a subgroup is in need of support and assistance to enhance social functioning and adjustment. Yet, even within this subgroup, survivors with different trajectories of social isolation will require different approaches at different points in time. Our findings also suggest that there are different degrees or gradients of social isolation experienced by participants, and future research that explores this in greater depth would provide essential evidence for the development of interventions tailored to individual's level of need. The challenges is, thus, to identify level of need and to provide interventions tailored to those needs, delivering the most intensive treatments to those who are most in need at the appropriate time. There is preliminary evidence that interventions can effectively teach social skills and promote social participation [69–71]. Clearly, intervention research is an essential next step.

There are limitations inherent in this research. All study participants were recruited in one Canadian province. Therefore, caution must be exercised when determining the relevance to other settings. Study results reflect the characteristics of study participants, who were recruited through follow-up clinics. It is possible that survivors attending these clinics are more likely to experience medical late effects and associated life disruptions, perhaps putting them at greater risk for social isolation. However, the perspectives of survivors who are severely neurocognitively and functionally disabled are underrepresented in this research, even though they are likely at high risk for social isolation, because all individuals who participated in this research judged themselves capable of taking part in an interview. It is also possible that survivors who consider themselves to be socially incompetent declined to participate in this research knowing that they would be interviewed.

Conclusion

This research lends support to the conclusion drawn by McDougal and Tsonis [72] that personal and environmental factors, like self-esteem, supportive care needs and societal attitudes, influence social outcomes and play an important role in the lives of childhood cancer survivors. Future prospective longitudinal research that follows survivors as they age would help illuminate the relationships between early experiences, late medical and psychological late effects and social outcomes in adulthood. Research that determines the degree of social isolation that is significant to survivors and warrants intervention would also complement the existing study. As with physical late effects, survivors might benefit from information about potential social late effects as well as screening for social late effects during long-term follow-up. Finally, the findings from this study suggest that one approach to providing support to prevent or mitigate social isolation is not appropriate—survivors with different trajectories will require different approaches at different points in time.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the survivors who took part in this study and shared their experiences for the benefit of others.

Funding information

This study was made possible by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Team for Supportive Cancer Care (#AQC83559). Dr. Fuchsia Howard holds a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Post Doctoral Research Trainee Award.

Disclosures

We have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ellison LF, De P, Mery LS, Grundy PE. Canadian cancer statistics at a glance: cancer in children. CMAJ. 2009;180:422–424. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, Zebrack B, Casillas J, Tsao JC, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clinic Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrera M, Shaw AK, Speechley KN, Maunsell E, Pogany L. Educational and social late effects of childhood cancer and related clinical, personal, and familial characteristics. Cancer. 2005;104:1751–1760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, van Dijk FJ. Adult survivors of childhood cancer and unemployment: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;107:1–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz KAP, Ness KK, Whitton J, Recklitis C, Zebrack B, Robison LL, et al. Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clinic Oncol. 2007;25:3649–3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zebrack BJ, Zevon MA, Turk N, Nagarajan R, Whitton J, Robison LL, et al. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of solid tumors diagnosed in childhood: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:47–51. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50:31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker CL. Social support and adolescent cancer survivors: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2007;16:1–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:229–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clinic Oncol. 2006;24:1105–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroenke CH, Quesenberry C, Kwan ML, Sweeney C, Castillo A, Caan BJ. Social networks, social support, and burden in relationships, and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis in the Life After Breast Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB. Layton JB Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;75:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foley KL, Farmer DF, Petronis VM, Smith RG, McGraw S, Smith K, et al. A qualitative exploration of the cancer experience among long-term survivors: comparisons by cancer type, ethnicity, gender, and age. Psychooncology. 2006;15:248–258. doi: 10.1002/pon.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derevensky J, Tsanos A, Handman M. Children with cancer: an examination of their coping and adaptive behavior. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1998;16:37–61. doi: 10.1300/J077V16N01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zebrack BJ, Zeltzer LK, Whitton J, Mertens AC, Odom L, Berkow R, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia, Hodgkin's disease, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:42–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JC, Recklitis C, Armstrong G, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidem, Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:435–446. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, Nicholson HS, Nathan PC, Zebrack B, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clinic Oncol. 2009;27:2390–2395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyer KH, Willard VW, Gross AM, Netson KL, Ashford JM, Kahalley LS, et al. The impact of attention on social functioning in survivors of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and brain tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:1290–1295. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Psychosocial functioning in pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:9–27. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannatta K, Gartstein MA, Short A, Noll RB. A controlled study of peer relationships of children surviving brain tumors: teacher, peer, and self ratings. J Pediatr Psychol. 1998;23:279–287. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.5.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulte F, Barrera M. Social competence in childhood brain tumor survivors: a comprehensive review. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1499–1513. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA, Wells RJ, Noll RB. Intensity of CNS treatment for pediatric cancer: prediction of social outcomes in survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:716–722. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkman TM, Palmer SL, Chen S, Zhang H, Evankovich K, Swain MA, et al. Parent-reported social outcomes after treatment for pediatric embryonal tumors: a prospective longitudinal study. J Clinic Oncol. 2012;30:4134–4140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin Newby W, Brown RT, Pawletko TM, Gold SH. Whitt JK Social skills and psychological adjustment of child and adolescent cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2000;9:113–126. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<113::AID-PON432>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Upton P, Eiser C. School experiences after treatment for a brain tumour. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vance YH, Eiser C, Horne B. Parents’ views of the impact of childhood brain tumours and treatment on young people’s social and family functioning. Clinic Child Psychol Psychiat. 2004;9:271–288. doi: 10.1177/1359104504041923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boydell KM, Stasiulis E, Greenberg M, Greenberg C, Spiegler B. I'll show them: the social construction of (in)competence in survivors of childhood brain tumors. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008;25:164–174. doi: 10.1177/1043454208315547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lancashire ER, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Glaser A, Hawkins MM. Educational attainment among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: a population-based cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:254–270. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, Zevon MA, Gibbs IC, Tersak JM, et al. Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97:1115–1126. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch SV, Kejs AM, Engholm G, Johansen C, Schmiegelow K. Educational attainment among survivors of childhood cancer: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. British J Cancer. 2004;91:923–928. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boman KK, Lindblad F, Hjern A. Long-term outcomes of childhood cancer survivors in Sweden: a population-based study of education, employment, and income. Cancer. 2010;116:1385–1391. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenzi M, McMillan AJ, Siegel LS, Zumbo BD, Glickman V, Spinelli JJ, et al. Educational outcomes among survivors of childhood cancer in British Columbia, Canada: report of the Childhood/Adolescent/Young Adult Cancer Survivors (CAYACS) Program. Cancer. 2009;115:2234–2245. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langeveld NE, Ubbink MC, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA, Voute PA, De Haan RJ. Educational achievement, employment and living situation in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer in the Netherlands. Psychooncology. 2003;12:213–225. doi: 10.1002/pon.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. The course of life of survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14:227–238. doi: 10.1002/pon.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackie E, Hill J, Kondryn H. McNally R Adult psychosocial outcomes in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and Wilms' tumour: a controlled study. Lancet. 2000;355:1310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Jenkinson HC, Hawkins MM. Long-term population-based marriage rates among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. Internatl J Cancer. 2007;121:846–855. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den BE, Kaspers GJL, van Dam EW, Braam KI. Huisman J Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17:506–511. doi: 10.1002/pon.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, Manley PE, Kenney LB. Recklitis CJ Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a report from Project REACH. J Sexual Med. 2013;10(8):2084–2093. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, Leonard M. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:814–822. doi: 10.1002/pon.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dieluweit U, Debatin K, Grabow D, Kaatsch P, Peter R, Seitz D, et al. Social outcomes of long-term survivors of adolescent cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1277–1284. doi: 10.1002/pon.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodgate R. Life is never the same: childhood cancer narratives. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15:8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherwin S. The politics of women’s health: exploring agency and autonomy. PressPhiladelphia, PA: Temple University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doane GH. Varcoe C Family nursing as relational inquiry: developing health-promoting practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.d'Agincourt-Canning L Genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: responsibility and choice. Qual Health Res 2006; 16:97–118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Howard A, Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL. Rodney P Preserving the self: the process of decision making about hereditary breast cancer and ovarian cancer risk reduction. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:502. doi: 10.1177/1049732310387798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilbar R, Gilbar O. The medical decision-making process and the family: the case of breast cancer patients and their husbands. Bioethics. 2009;23:183–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Surbone A. The difficult task of family caregiving in oncology: exactly which roles do autonomy and gender play? Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:617–619. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0510-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Surbone A. Telling the truth to patients with cancer: what is the truth? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:944–950. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70941-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surbone A. Anonymous Management of Breast Cancer in Older Women. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. Kagawa-Singer M Culture, Ethnicity, and Race: Persistent Disparities in Older Women with Breast Cancer; pp. 349–369. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anne Donchin Autonomy and interdependence: quandaries in genetic decision making. In: Catriona Mackenzie, Natalie Stoljar. Relational autonomy: feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency, and the social self, New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- 53.Morse JM. Field PA Qualtiative research methods for health professionals. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strauss A. Corbin J Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Speechley KN, Barrera M, Shaw AK, Morrison HI, Maunsell E. Health-related quality of life among child and adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. J Clinic Oncol. 2006;24:2536–2543. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Dijk J, Imhof SM, Moll AC, Ringens PJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Rijmen F, et al. Quality of life of adult retinoblastoma survivors in the Netherlands. Health Quality Life Outcomes. 2007;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barrera M, Schulte F, Spiegler B. Factors influencing depressive symptoms of children treated for a brain tumor. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26:1–16. doi: 10.1300/J077v26n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langeveld N, Grootenhuis M, Voute P, De Haan R, Van Den Bos C. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:867–881. doi: 10.1002/pon.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boman KK, Hörnquist L, De Graaff L, Rickardsson J, Lannering B, Gustafsson G Disability, body image and sports/physical activity in adult survivors of childhood CNS tumors: population-based outcomes from a cohort study. J Neurooncol 2013:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Pendley JS, Dahlquist LM, Dreyer Z. Body image and psychosocial adjustment in adolescent cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:29–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Banner LM, Mackie EJ, Hill JW. Family relationships in survivors of childhood cancer: resource or restraint? Patient Educ Couns. 1996;28:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(96)00901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orbuch TL, Parry C, Chesler M, Fritz J, Repetto P. Parent-child relationships and quality of life: resilience among childhood cancer survivors*. Fam Relat. 2005;54:171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-6664.2005.00014.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill J, Kondryn H, Mackie E, McNally R, Eden T. Adult psychosocial functioning following childhood cancer: the different roles of sons’ and daughters’ relationships with their fathers and mothers. J Child Psychol Psychiat. 2003;44:752–762. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kazak AE. Evidence-based interventions for survivors of childhood cancer and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:29–39. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prevatt FF, Heffer RW, Lowe PA. A review of school reintegration programs for children with cancer. J School Psychol. 2000;38:447–467. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00046-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meyler E, Guerin S, Kiernan G, Breatnach F. Review of family-based psychosocial interventions for childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:1116–1132. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Varni JW, Katz ER, Colegrove R, Dolgin M. The impact of social skills training on the adjustment of children with newly diagnosed cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1993;18:751–767. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/18.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barakat LP, Kazak AE, Meadows AT, Casey R, Meeske K, Stuber ML. Families surviving childhood cancer: a comparison of posttraumatic stress symptoms with families of healthy children. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:843–859. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khan F, Amatya B, Rajapaksa I, Ng L. Outcomes of social support programs in brain cancer survivors in an Australian community cohort: a prospective study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;1:24–33. doi: 10.14312/2052-4994.2013-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDougall J, Tsonis M. Quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review of the literature (2001–2008) Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1231–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]