Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the prevalence, spatial patterns and clustering in the distribution of soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections, and factors associated with hookworm infections in a tribal population in Tamil Nadu, India.

Methods

Cross-sectional study with one-stage cluster sampling of 22 clusters. Demographic and risk factor data and stool samples for microscopic ova/cysts examination were collected from 1237 participants. Geographical information systems mapping assessed spatial patterns of infection.

Results

The overall prevalence of STH was 39% (95% CI 36%–42%), with hookworm 38% (95% CI 35–41%) and Ascaris lumbricoides 1.5% (95% CI 0.8–2.2%). No Trichuris trichiura infection was detected. People involved in farming had higher odds of hookworm infection (1.68, 95% CI 1.31–2.17, P < 0.001). In the multiple logistic regression, adults (2.31, 95% CI 1.80–2.96, P < 0.001), people with pet cats (1.55, 95% CI 1.10–2.18, P = 0.011) and people who did not wash their hands with soap after defecation (1.84, 95% CI 1.27–2.67, P = 0.001) had higher odds of hookworm infection, but gender and poor usage of foot wear did not significantly increase risk. Cluster analysis, based on design effect calculation, did not show any clustering of cases among the study population; however, spatial scan statistic detected a significant cluster for hookworm infections in one village.

Conclusion

Multiple approaches including health education, improving the existing sanitary practices and regular preventive chemotherapy are needed to control the burden of STH in similar endemic areas.

Keywords: soil-transmitted helminths, hookworm, Ascaris, Trichuris, intestinal parasites, tribal

Introduction

Soil-transmitted helminths, namely roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworms (Trichuris trichiura) and hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale), affect more than 2 billion people worldwide (WHO 2012b,c). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, over 1 billion people are infected with roundworm, 740 million with hookworm and 795 million with whipworm (WHO 2012c). In 2001, the World Health Assembly of the WHO resolved to achieve a target of 75% coverage of preventive chemotherapy for pre-school and school-aged children by the year 2010 in all its regions (WHO 2001), but globally only 31% has been achieved, with 38% in India (WHO 2012a). Lack of resources in terms of health infrastructure, manpower, drugs, political will, traditional beliefs and customs are some of the common barriers to achieving the target. Non-availability of accurate information on the prevalence or burden of disease in the community is another major obstacle to the timely implementation of preventive strategies.

The prevalence of STH infections among Indian tribal populations is presented in Table 1. Recent unpublished data from Vellore and Thiruvannamalai districts of southern India, among school going children, show a prevalence of <10% with strong evidence of clustering (Kattula et al. 2013). The prevalence in the tribal population in these districts is unknown even though they have a number of high risk behaviours including open defecation, employment in agriculture, and close contact with livestock and domestic animals.

Table 1.

Soil-transmitted helminth prevalence among Indian tribal populations

| Place | Year | Prevalence of Soil-Transmitted Helminths (STH) |

Age groups, Study population and sample size |

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh | 1988–1993 | Overall hookworm – 15.6% | All age groups belonging to Abujhmaria, Baiga and Bharia tribes (N = 9653) | (Chakma et al. 2006) | |||

| Andaman and Nicobar | 1996 | Hookworm – 2.4%, Ascaris lumbricoides – 70.7% and Trichuris trichiura- 24.4% | Age 0–6 years Pre-school children Among Nicobarese (N = 41) | (Sugunan et al. 1996) | |||

| Hookworm – 4%, Ascaris lumbricoides – 28% and Trichuris trichiura – 32% | Adults of Nicobarese and Onge tribes N = 46 | ||||||

| Meghalaya (Nongkya and Umsning) | 1996–1999 | Pre-monsoon (March– June) | Monsoon (July– October) | Post-monsoon (November– February) | All age groups. Three tribal populations living in Nongkya, Sutnga and William Nagar (N = 2087) | (Lyndem et al. 2002) | |

| Hookworm | 31.8% | 41.3% | 45.6% | ||||

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 43.2% | 48.2% | 52.6% | ||||

| Trichuris trichiura | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.9% | ||||

| Andaman and Nicobar | 1997 | Hookworm – 0%, Ascaris lumbricoides 90%, Trichuris trichiura – 37.5% and Mixed infection – 27.5% | All age groups. Onge tribes N = 40 | (Rao et al. 2006) | |||

| Madhya Pradesh | 2000 | Hookworm – 16.3% and Ascaris lumbricoides – 18.5% | School going children (6–14 years) of Baiga, Abuihmadia and Bharia tribes N = 409 | (Chakma et al. 2000) | |||

| Madhya Pradesh (Kundam block, Jabalpur District) | 2000–2001 | Intestinal parasites 59.5% Mixed infections reported (hookworm commonest) | Adolescent boys and girls from 11 to 19 years N = 783 | (Rao et al. 2005) | |||

| Orissa | 2002–2003 | Hookworm Bondo tribes – 21%, Didayi tribes – 18.7%, Juanga tribes – 14% and Kondha tribes –18.2% | All age groups of four primitive tribes of Orissa | (Indian Council for Medical Research 2003) | |||

| Kerala | 2002 | Area | All age groups of Kani and Malampandaram tribes living two areas, N = 258 | (Farook et al. 2002) | |||

| Achankovil | Kottur | ||||||

| Hookworm | 58.8% | 18.6% | |||||

| Ascaris lumbricoides | 41.1% | 74.4% | |||||

| Rajasthan (Dungarpur district) | 2006 | Hookworm – 16.6%, Ascaris lumbricoides – 36.7% and Trichuris trichiura – 25.4% | Age 5–50 years. Tribal individuals N = 870 | (Choubisa & Choubisa 2006) | |||

| Rajasthan (Udaipur district) | 2010–2011 | Hookworm – 0.9%, Ascaris lumbricoides – 4.5% and Trichuris trichiura – 0.4% | All age groups of Bhil tribal individuals N = 224 | (Choubisa et al. 2012) | |||

Heterogeneity in the distribution of STH infections at the household and community levels has been documented previously (Saathoff et al. 2005; Brooker et al. 2006; Pullan et al. 2008, 2010). Studies from Brazil and Uganda have demonstrated strong evidence of clustering of helminth infections, both within and between households (Brooker et al. 2006; Pullan et al. 2008, 2010). In contrast, a study in rural Cote d’Ivoire reported a random distribution (Utzinger et al. 2003). No studies have, however, been conducted to determine the spatial patterns and risk factors of STH infection in a tribal community in India.

The primary objectives of this study were to 1) estimate the prevalence of STH infections among children aged 1–15 years and persons of age 16 and above, 2) study the factors associated with STH infections and 3) identify spatial patterns in the distribution of STH infections in the tribal population of Jawadhu Hills, Vellore/Thiruvannamalai districts of Tamil Nadu, India.

Methods

Study area and population

Jawadhu Hills (JH) is an area located on the borders of Vellore and Thiruvannamalai districts of Tamil Nadu in southern India. A total of 80 000 people, mostly Malaiyali tribes, predominantly farmers, live in these hills. The average rainfall is 1100 mm and average temperature is 29 °C. JH has 11 panchayats (groups of villages with a common administration) with about 250 villages; each village has 15–100 households. The area has poor road access, lacks adequate potable drinking water and has poor sanitation facilities, typical of any tribal village in a developing country. In 2008, the Community Health Department (CHD), Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, updated its census list and began to provide primary health care and referral services in 106 villages in this area.

Study design and data collection

A cross-sectional study design with single-stage cluster sampling was used to recruit participants from these villages. Of the 106 villages covered by CHD, those that were accessible either by road or a maximum of 45-minute walks from the road and had more than 150 residents were selected. A minimum of 30 eligible households per village was recruited. In each household, one child participant of the age 1–15 years and one adult, older than 15 years, who were willing to participate, were recruited. The study was carried out from November 2011 to April 2012.

The CMC Institutional Review Board approved the study. Additionally, local leaders were consulted and permission for the study was obtained. All study participants provided written informed consent. Participants of 18 years and older signed their own consent form. Parental consent was obtained for participants <18 years. For participants between 7 and 17 years, written assent for participation was obtained in addition to parental informed consent. Participants were visited at home by field workers, who recorded demographic data and behavioural patterns using a structured questionnaire, which had previously been piloted for language and comprehension. The socio-economic status (SES) of the participants was assessed using the CHAD SES scoring scale, which has been validated for rural areas of Vellore (Mohan & Muliyil 2009). Each family was scored on the following five characteristics: caste, type of house, occupation and education of the head of the household, and land ownership (in acres). They were then classified as low, middle or high SES categories using the 33rd and 66th centile of the study population as cut-offs. For analysis, participants in the low and middle SES categories were grouped together.

Data on footwear usage during each of the following activities were captured: defaecation, outdoor activities, going to school, travel outside of the village, and farming. A composite footwear usage score, ranging from 0 to 5, was then computed using these 5 parameters, where a score of 0 meant no footwear usage during any of the activities and 5 meant usage of footwear during all activities. Median scores were calculated separately for adults and children, and subjects with a total score less than the median cut-off were considered as ‘poor’ footwear users.

Stool sample collection and testing

The participants were given containers and visited at home the following day to collect the stool samples. Each participant was requested to collect five samples on alternate days. The samples were transported with ice packs to the parasitology laboratory in CMC for microscopic examination, both by direct saline/iodine preparations and after formal-ether concentration. Any participant with any STH (Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, hookworm) in any sample was considered positive.

Data management and analysis

Double data entry by two operators used Epi-Info 3.5.1 (CDC, GA, USA), and the two data sets were compared and cross-verified with the questionnaire. Analysis used SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) and STATA 10 (StataCorp., TX, USA) software. Statistical tests were carried out at 5% significance level (P < 0.05) and confidence interval (CI) set at 95%. Bivariate analyses were performed to identify the association between risk factors and the outcome. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to test the statistical significance of the associations. The effect of household clustering was accounted for by using the survey (‘svy’) commands in STATA software, which takes into account the complex survey design for the estimation of 95% CI (Kreuter & Richard 2007). Univariate logistic regression was performed for selected variables and odds ratio (with 95% CI) calculated to ascertain the strength of association between the exposure and outcome variable. Multiple logistic regression analysis was also performed to build a model using predictors that were statistically significant or near significant.

Spatial mapping and analysis

The boundaries of the study villages, water sources, taps, important landmarks and commonly used defaecation fields were mapped using a hand-held global positioning system (GPS) receiver Garmin GPS V (Garmin International Inc., KS, USA). The ‘waypoints’ and ‘track points’ provided by the GPS were downloaded using GPS Utility 4.10.4 software (GPS Utility Ltd., Southampton, UK). They were then converted to ‘shapefiles’ using ArcView GIS 10 software (Environmental systems Research Inc., CA, USA). The attributes were then layered to ascertain spatial relationships.

Spatial clustering of hookworm and Ascaris cases was ascertained through a discrete Poisson model with villages as units, using SaTScan 9.1.1 software (http://www.satscan.org/) (Kulldorff 1996). The centroids for the villages were used as location identifiers. An initial unadjusted analysis, followed by adjustment for potential confounding variables such as the proportions of subjects in each village involved in agricultural work, with un-trimmed nails, with pets at home, who lived in households with six or more members, who never used soap for hand washing after defecation, had poor footwear usage practice and belonged to low and middle socio-economic status, was performed.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 1237 subjects were recruited from 680 households. Data and samples were obtained from both children and adults in 557 (81.9%) households, from children only in 63 (9.3%) households and from adults only in 60 (8.8%) households. Of 1237 participants, 617 (49.1%) were adults and 620 (50.9%) were children, with equal proportions of males (49.9%) and females (50.1%). The average number of participants per cluster was 56, with a range between 25 and 112. Of 1237 participants, 45%, 11%, 12%, 12% and 19% provided 5, 4, 3, 2 and 1 sample, respectively. The baseline household characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline household characteristics of the study population in Jawadhu Hills

| Characteristic | Frequency (N = 680) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Caste | |

| Scheduled caste and scheduled tribes | 679 (99.9) |

| Agricultural/artisan caste | 1 (0.2) |

| Type of family | |

| Nuclear | 642 (94.4) |

| Joint | 37 (5.4) |

| Extended | 1 (0.2) |

| Type of house | |

| Hut | 219 (32.2) |

| Thatched | 227 (33.4) |

| Kutcha | 13 (1.9) |

| Tiled house | 71 (10.4) |

| Terraced | SO (7.4) |

| Government built house | 100 (14.7) |

| Type of electrification | |

| Paid | 23 (3.4) |

| Free | 640 (94.1) |

| No power connection | 17 (2.5) |

| Presence of toilet | |

| Yes | 4 (0.6) |

| No | 676 (99.4) |

| Socio-economic status | |

| Low | 180 (26.5) |

| Mid | 271 (39.9) |

| High | 229 (33.7) |

| Presence of animals | |

| Yes | 568 (83.5) |

| No | 112 (16.5) |

| Presence of pigs | |

| Yes | 327 (48.1) |

| No | 353 (51.9) |

Prevalence of STH infections

The overall prevalence of STH infections was 39% (95% CI 36–42%). Hookworm was the predominant STH identified with a prevalence of 38% (95% CI 35–41%), followed by Ascaris lumbricoides with a prevalence of 1.5% (95% CI 0.8–2.2%). Five (0.4%) people had mixed infections with both hookworm and Ascaris. None of the participants were infected with Trichuris trichiura. The prevalence of STH infections across the study clusters is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics and prevalence rates of soil-transmitted helminths across the study clusters of Jawadhu Hills

| Percentage of subjects |

Prevalence percentage |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | Villages | Total Population |

Study subjects |

Total Stool samples |

Male | Living in overcrowded houses |

Living in close contact with animals |

Low SES category |

Had de-worming recently |

With a toilet at home |

STH | Hookworm | Ascaris |

| 1 | Neeplampattu Amirthi Palapiraampattu |

494 | 71 | 280 | 38.0 | 29.6 | 83.1 | 59.2 | 8.6 | 4.2 | 59.2 | 59.2 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Pallathur Mallimadu Nagalur |

472 | 79 | 273 | 63.3 | 34.2 | 83.5 | 67.1 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 64.6 | 60.8 | 5.1 |

| 3 | Nadupattu Muthalaimadu |

402 | 42 | 159 | 59.5 | 50.0 | 88.1 | 88.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 0.0 |

| 4 | Keezh- sarananguppam Thaathankuppam |

565 | 70 | 230 | 52.9 | 28.6 | 68.6 | 54.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.7 | 35.7 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Melkanavayur Kavampattu |

493 | 71 | 209 | 46.5 | 45.1 | 49.3 | 73.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.2 | 26.8 | 1.4 |

| 6 | Eriyur Saramarathur |

250 | 60 | 247 | 45.0 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 43.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 55.0 | 55.0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | Pulikondranvazhi | 165 | 42 | 191 | 35.7 | 38.1 | 76.2 | 69.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 47.6 | 47.6 | 0.0 |

| 8 | Mutnaattur Keezhnadanur Patnur |

706 | 52 | 168 | 44.2 | 32.7 | 53.8 | 59.6 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 32.7 | 0.0 |

| 9 | Nambiampattu | 726 | 49 | 200 | 42.9 | 34.7 | 93.9 | 79.6 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 38.8 | 38.8 | 0.0 |

| 10 | Kalathukottai Chinnaveerapattu Periaveerappattu |

630 | 54 | 164 | 38.9 | 20.4 | 81.5 | 79.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.2 | 33.3 | 1.9 |

| 11 | Melnambiampattu Velliyur |

427 | 50 | 167 | 46.0 | 18.0 | 90.0 | 82.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 0.0 |

| 12 | Keezhkovilur | 211 | 42 | 179 | 38.1 | 23.8 | 100.0 | 59.5 | 7.3 | 4.8 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 0.0 |

| 13 | Kovilaandur | 304 | 36 | 122 | 50.0 | 11.1 | 100.0 | 75.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 |

| 14 | Mandapaarai Kallipaarai |

417 | 55 | 174 | 49.1 | 21.8 | 100.0 | 89.1 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 41.8 | 36.4 | 9.1 |

| 15 | Arasavalli | 192 | 45 | 185 | 62.2 | 33.3 | 91.1 | 31.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 42.2 | 31.1 | 11.1 |

| 16 | Bargur | 336 | 49 | 163 | 46.9 | 10.2 | 95.9 | 87.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.7 | 32.7 | 0.0 |

| 17 | Puthupattu | 917 | 112 | 354 | 58.0 | 32.1 | 62.5 | 60.7 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 0.0 |

| 18 | Veerappanur | 494 | 37 | 75 | 45.9 | 54.1 | 94.6 | 27.0 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 0.0 |

| 19 | Theerthanur | 339 | 25 | 72 | 44.0 | 36.0 | 84.0 | 60.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 0.0 |

| 20 | Odamangalam | 374 | 99 | 363 | 56.6 | 47.5 | 100.0 | 74.7 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 52.5 | 51.5 | 3.0 |

| 21 | Vilankuppam | 230 | 30 | 125 | 53.3 | 13.3 | 100.0 | 73.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 |

| 22 | Patraikkadu Amattankollai |

313 | 67 | 246 | 41.8 | 16.4 | 80.6 | 56.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.3 | 40.3 | 0.0 |

| Overall | 9457 | 1237 | 4346 | 49.1 | 30.6 | 83.3 | 66 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 39.3 | 38.2 | 1.5 | |

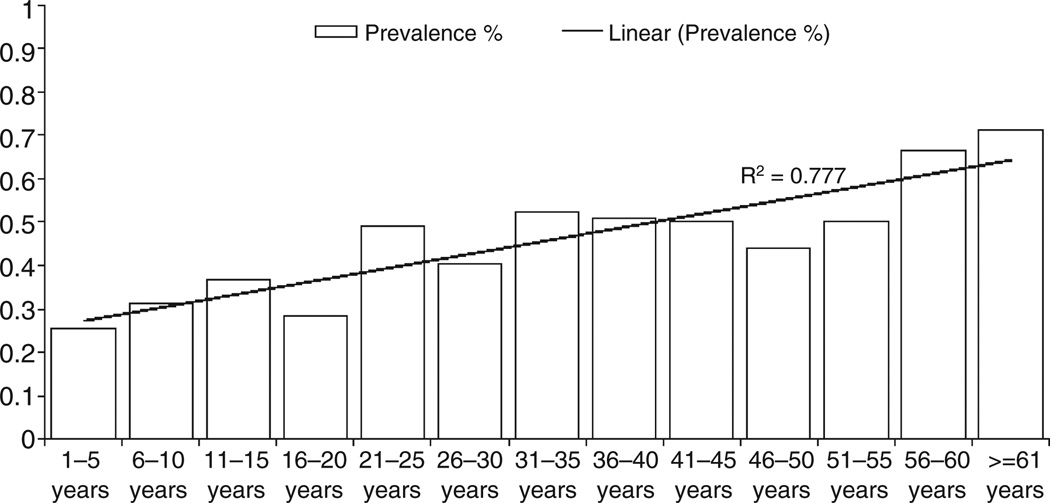

The prevalence of hookworm infection increased with increasing age (χ2 test for linear trend, P < 0.001; Figure 1). However, no relationship between age and Ascaris lumbricoides infection was observed (χ2 test for linear trend, P = 0.129). There was no significant association between gender and hookworm (P = 0.147) and Ascaris (P = 0.881) infections.

Figure 1.

Prevalence and linear trend of soil-transmitted helminth infections across the age categories.

Risk factors for STH infection

In the univariate analysis, people who worked on farms had higher odds of acquiring hookworm infections when compared to people not doing any agricultural work (OR 1.68; 95% CI 1.31–2.17; P < 0.001). When compared to people who worked on farms for 1–2 days per week, people who worked for 3–4 days and more than 4 days had higher odds of 1.37 times (95% CI 0.94–1.99, P = 0.098) and 1.61 times (95% CI 1.04– 2.47, P = 0.032), respectively, of hookworm infection. Presence of untrimmed long dirty nails, not washing hands before eating, usage of a designated area for defaecation, pig rearing and having domestic animals were not significantly associated with an increased risk of hookworm infection. Washing hands with soap and water after defaecation had a protective effect, as people who never washed hands with soap and water had odds of 1.84 (95% CI 1.27–2.67, P = 0.001) for hookworm infection, which remained statistically significant even after adjusting for other variables in the multivariate model. Having a cat as a pet increased odds to 1.55 (95% CI 1.10–2.18, P = 0.011), which remained significant in the multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with hookworm infections by multivariate logistic regression analysis in the study population of Jawadhu Hills

| Variable | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Sig. | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category Children (Reference) | ||||

| Adults | 2.045 (1.61–2.58) | <0.001 | 2.31 (1.80–2.96) | <0.001 |

| Socio-economic status High (Reference) | ||||

| Low | 0.97 (0.76–1.24) | 0.867 | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) | 0.828 |

| Overcrowding 5 or fewer members (Reference) | ||||

| Six or more members | 1.09 (0.85–1.39) | 0.494 | 1.07 (0.83–1.39) | 0.570 |

| Pig rearing Not rearing (Reference) | ||||

| Rearing | 0.94 (0.75–1.18) | 0.617 | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) | 0.716 |

| Presence of cat at home No (Reference) | ||||

| Yes | 1.41 (1.02–1.94) | 0.032 | 1.55 (1.10–2.18) | 0.011 |

| Peeling vegetables before cooking Yes (Reference) | ||||

| Not peeling | 2.71 (0.64–11.36) | 0.157 | 1.36 (0.27–6.76) | 0.701 |

| Presence of untrimmed nails No (Reference) | ||||

| Yes | 0.79 (0.62–1.01) | 0.069 | 0.80 (0.61–1.04) | 0.097 |

| Foot wear usage during various activities Good (Reference) | ||||

| Poor usage | 1.07 (0.85–1.36) | 0.524 | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) | 0.413 |

| Using designated area for defaecation Never (Reference) | ||||

| Regular usage | 0.82 (0.53–1.26) | 0.376 | 0.71 (0.44–1.14) | 0.160 |

| Washing hands with soap and water after defaecation Yes (Reference) | ||||

| No | 1.34 (0.96–1.87) | 0.085 | 1.84 (1.27–2.67) | 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.489 | 0.014 | ||

People with a cat at home were also found to have a higher risk of Ascaris infection (OR 4.38, 95% CI 1.74–11.07, P = 0.001) in the univariate analysis. None of the other factors were found to be significantly associated with Ascaris infection.

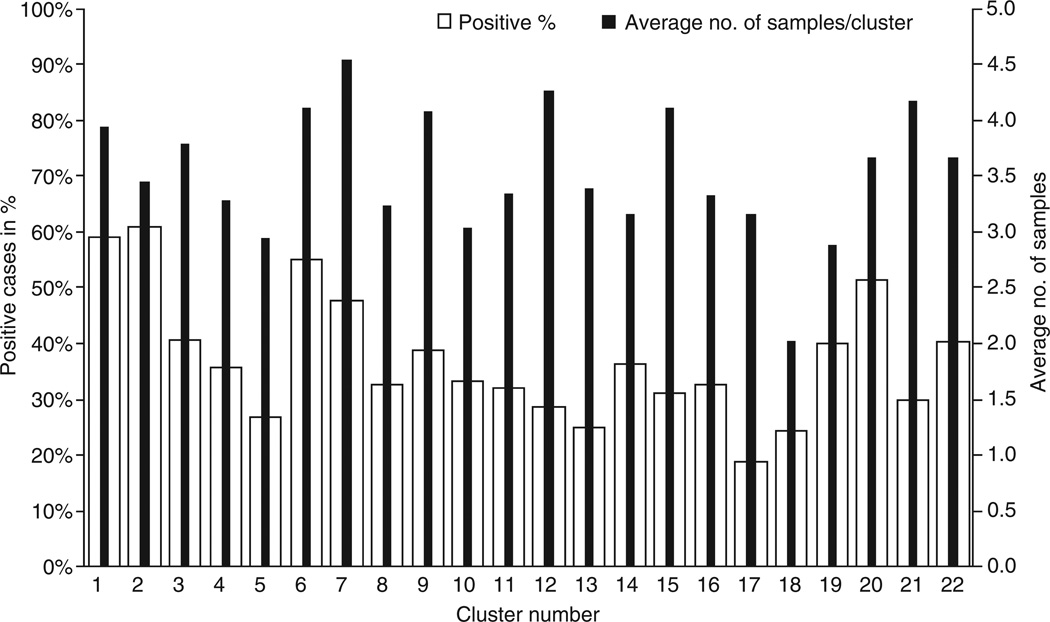

Analysis for presence of household clustering

The average number of samples collected was 3.5 (Standard deviation (SD) –1.6) per participant, this varied among clusters from 2 (SD –1.2) to 4.5 (SD –1.2) per individual in the cluster. STH positivity ranged from 19 to 64% among the 22 study clusters (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infections and number of samples obtained across the clusters.

Assessment of the effect of clustering showed a design effect of 1.04, indicating that there was no evidence of household clustering of STH cases. Similarly, no household clustering of either hookworm (design effect 1.04) or Ascaris (design effect 1.24) cases was noticed, when ascertained separately.

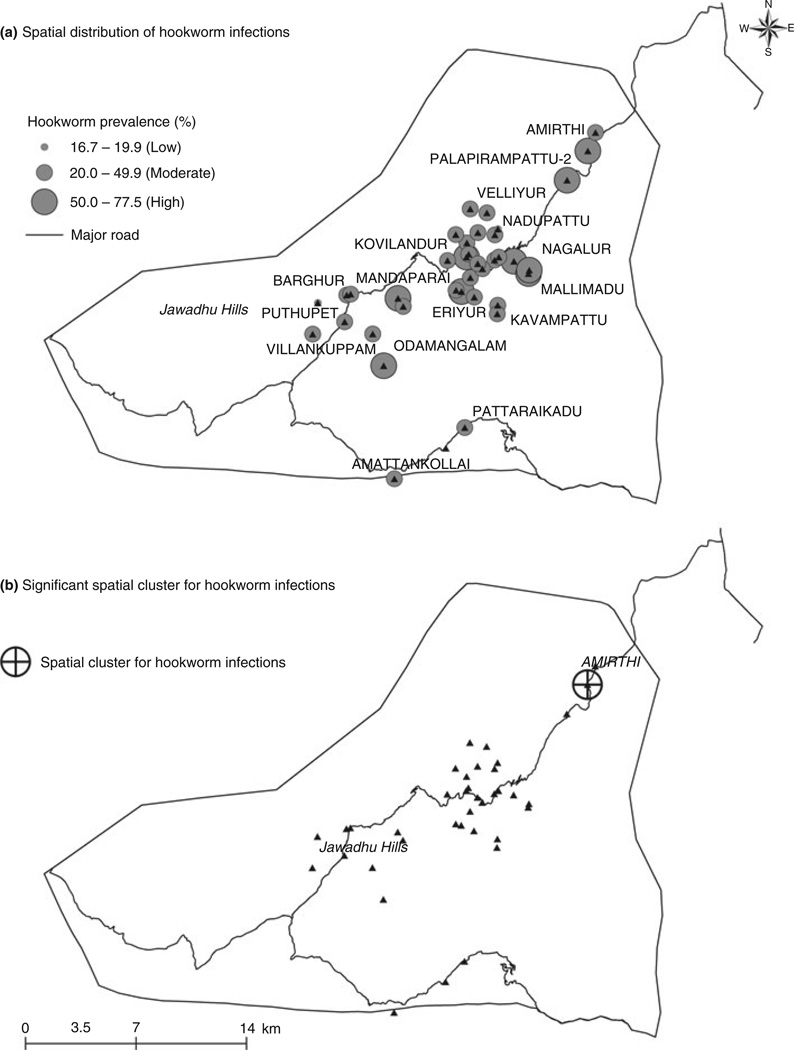

Spatial patterns and clustering of hookworm infections

The prevalence rates for hookworm infections ranged from 20 to <50% in a majority (70%, 26/37) of the study villages; 24% (9/37) of the villages had hookworm positivity rates 50% and above. The spatial pattern of hookworm infections across the study areas is presented in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

(a) Spatial distribution of hookworm infections in the study villages. (b) Spatial clustering of hookworm infection in the study area.

Unadjusted analysis using SaTScan identified significant spatial clustering of hookworm cases in one village (RR = 2.10; P < 0.05) as presented in Figure 3b. However, this clustering was not apparent on adjustment for potential confounders, which could suggest that the clustering of cases was possibly due to socio-demographic and behavioural differences between villages. No spatial clustering of cases of Ascaris lumbricoides was observed in the study villages.

Discussion

Soil-transmitted helminths generally infect people who live in poverty with poor sanitary conditions and lack of adequate safe water (Sorensen et al. 1996). Socioeconomic status and socio-cultural factors are significantly associated with STH infections (Schad et al. 1983; de Silva et al. 2003). In this study, there was a moderate-to-high prevalence of STH in the tribal population surveyed, almost entirely comprising of hookworm infection. The infection rates increased significantly with age, from childhood to school age or adolescent and further in the older age groups. This increase in prevalence with age has important public health consequences especially in developing countries (Gandhi et al. 2001; Bethony et al. 2002), where the populations most affected are the economically productive age groups, but preventive chemotherapy programmes primarily target pre-school and school age children (WHO 2001).

No infections with Trichuris trichiura were detected; this could be due to the geographical distribution of these helminths, as Trichuris and Ascaris are more common in urban areas and hookworm infections are predominant in rural settings (Albonico et al. 1997). Studies have shown a gender difference in hookworm infection rates with males having higher burden than females (Albonico et al. 1997; Hotez et al. 2003). In our study, we did not find significant difference in the burden between males and females, possible reasons being that in this tribal community, men and women have similar occupations and behaviour patterns. There was no significant association between SES and STH infections in the univariate analysis, possibly because of the homogeneity of the Malaiyali tribal community, as 99.9% (679/680) of the households were from the same community. The SES scale used in this study was originally designed and validated in rural areas of Vellore district where a caste hierarchy system exists generally, and even though agriculture is the predominant occupation, a substantial number of families depend on various other non-agricultural activities for their daily living. The tribal population in this study are a homogenous population belonging to the same tribe who settled in this hilly area a few hundred years ago and depend on agriculture as their main source of livelihood. Access to education has been very limited in the past and has only gradually begun to improve in recent years. The SES scale used in this study has its limitations as the components of caste, educational level of the head of the household and type of house were similar for the majority of the families in these tribal communities.

Studies have shown that about 5–15 min of dermal contact is required for the hookworm to pierce the skin and gain entry (Matthews 1982; Hotez et al. 1990). The timing and duration of contact with infested soil plays a major role in determining the acquisition of hookworm infection (Schad et al. 1983). This study found a significantly higher risk among farm workers with people working for 3–4 days and more than 4 days per week experiencing 40% and 61% higher risks of acquiring hookworm infection respectively compared to people working for 1–2 days, thereby suggesting an exposure related dose–response.

Although footwear usage is a protective factor reported in many studies, there are some concerns that this could be an over estimate (Bethony et al. 2002; Hotez et al. 2003). In this study, no association between footwear usage and hookworm infection was noticed.

A strong association between toilet usage and decreased STH infections has been demonstrated in developing countries. A systematic review of 36 studies revealed a significant overall protective effect of 51% for STH infections in general and 60% for hookworm infections (Ziegelbauer et al. 2012). In this study, as only six participants used toilets, we could not assess the association between toilet usage and STH infections.

Multiple stool sample examinations are better in finding the true prevalence of STH infections (Kang et al. 1998; Knopp et al. 2008). In this study, although the overall prevalence was 39% for all subjects, the prevalence among subjects who gave all five samples was 49% (277/559), indicating that the actual prevalence of STH infection may be higher than reported here.

A strong clustering of cases was reported in a Brazilian study, where 48% of the subjects who had STH infections were from 5% of the households in the study area in a 690 metre radius (Souza et al. 2007). STH clustering was associated with poor socio-economic status and overcrowding of households (Souza et al. 2007). Spatial clustering of intestinal parasites has also been reported in Tajikistan among primary school children (Matthys et al. 2011). This study also detected a significant spatial cluster for hookworm infection, although this was no longer significant after adjustment for potential confounders.

A major limitation of this study was the inability to ascertain the intensity of STH infections in the study population. This study was conducted in a difficult-to-reach tribal area with little or absent health infrastructure, and hence, stool samples had to be transported to the central laboratory in Vellore (approximately 60 km away) for processing. Studies have shown that time delay between excretion and laboratory processing of stool samples significantly decreases the faecal egg count, especially for hookworm infection (Dacombe et al. 2007; Krauth et al. 2012). As this could have resulted in a misclassification of the worm intensity, only prevalence was assessed. Future studies should, however, consider measuring worm intensity for a better assessment of the impact of STH in this population.

Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infections in this tribal area was much higher (39%) and had a marked predominance of hookworm when compared to the regional estimates (7%) (Kattula et al. 2013). This relatively high prevalence of hookworm appears associated with socio-economic, socio-cultural, occupational, environmental and behavioural factors. Compared to urban and rural areas of the developing countries, the tribal population has poorer facilities for sanitation, safe drinking water and access to health care.

Given the linear association between age and hookworm prevalence, periodic mass deworming of the entire population, as opposed to the current strategy of selective deworming of the pre-school and school-aged children, might be more effective in hookworm endemic areas. Long-term sustainability of any hookworm control programme will, however, require improvement in hygiene and sanitary conditions of the affected population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants. We are grateful to field workers, the field co-ordinator Mr. G. George Martin and Mr. J. Senthilkumar who collected data, the statisticians Mr. R. Karthikeyan, Mr. V. Srinivasan, Mr. V. Vasanthakumar who helped in entering the data and analysis and Mrs. S. Selvi, Mrs. M. L. Lilly Michael Rani, Mr.Umar Ali, Ms. K. Divya who helped with the laboratory testing.

References

- Albonico M, Chwaya HM, Montresor A, et al. Parasitic infections in Pemba Island school children. East African Medical Journal. 1997;74:294–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethony J, Chen J, Lin S, et al. Emerging patterns of hookworm infection: influence of aging on the intensity of Necator infection in Hainan Province, People’s Republic of China. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35:1336–1344. doi: 10.1086/344268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker S, Alexander N, Geiger S, et al. Contrasting patterns in the small-scale heterogeneity of human helminth infections in urban and rural environments in Brazil. International Journal of Parasitology. 2006;36:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakma T, Rao PV, Tiwary RS. Prevalence of anaemia and worm infestation in tribal areas of Madhya Pradesh. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 2000;98:570–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakma T, Rao PV, Meshram PK, Singh SB. Health and nutrition profile of tribals of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Proceedings of National Symposium on Tribal Health; Jabalpur. Regional Medical Research Center for Tribals; 2006. [accessed 22 November 2012]. pp. 197–209. Available at: http://www.rmrct.org/files_rmrc_web/centre%27s_publications/NSTH_06/NSTH06_26.T.Chakma.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Choubisa SL, Choubisa L. Intestinal helminthic infections in tribal population of Southern Rajasthan, India. Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2006;30:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Choubisa SL, Jaroli VJ, Choubisa P, Mogra N. Intestinal parasitic infection in Bhil tribe of Rajasthan, India. Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2012;36:143–148. doi: 10.1007/s12639-012-0151-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacombe RJ, Crampin AC, Floyd S, et al. Time delays between patient and laboratory selectively affect accuracy of helminth diagnosis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;101:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farook MU, Sudharmini S, Remadevi S, Vijayakumar K. Intestinal helminthic infestations among tribal populations of Kottoor and Achankovil areas in Kerala (India) The Journal of Communicable Diseases. 2002;34:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi NS, Chen JZ, Koshnood K, et al. Epidemiology of Necator americanus hookworm infections in Xiulongkan Village, Hainan Province, China: high prevalence and intensity among middle-aged and elderly residents. Journal of Parasitology. 2001;87:739–743. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0739:EONAHI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P, Haggerty J, Hawdon J, et al. Metalloproteases of infective Ancylostoma hookworm larvae and their possible functions in tissue invasion and ecdysis. Infection and Immunity. 1990;58:3883–3892. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3883-3892.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez PJ, De Silva N, Brooker S, Bethony J. Disease Control Priorities Project. Working Paper No. 3. Fogarty International Center. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2003. [accessed 22 November 2012]. Soil transmitted helminth infections: The nature, causes and burden of the condition. Available at: http://www.dcp2.org/file/19/ [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council for Medical Research. Health status of primitive tribes of Orissa. [accessed 22 November 2012];ICMR Bulletin. 2003 :33. Available at: http://icmr.nic.in/BUOCT03.pdf.

- Kang G, Mathew MS, Rajan DP, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in rural southern Indians. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1998;3:70–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattula D, Sarkar R, Ajjampur SS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for soil transmitted helminth infection among school children in south India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2013 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopp S, Mgeni AF, Khamis LS, et al. Diagnosis of soil-transmitted helminths in the era of preventive chemotherapy: effect of multiple stool sampling and use of different diagnostic techniques. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2008;2:e331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauth SJ, Coulibaly JT, Knopp S, Traore M, N’Goran EK, Utzinger J. An in-depth analysis of a piece of shit: distribution of Schistosoma mansoni and hookworm eggs in human stool. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6:el969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter F, Richard V. A survey on survey statistics: what is done and can be done in Stata. The Stata Journal. 2007;7:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kulldorff M. A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods. 1996;26:1481–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Lyndem LM, Tandon V, Yadav AK. Hookworm infection among the rural tribal populations of Meghalaya (Northeast India) Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2002;26:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BE. Skin penetration by Necator americanus larvae. Zeitschrift fur Parasitenkunde. 1982;68:81–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00926660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys B, Bobieva M, Karimova G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of helminths and intestinal protozoa infections among children from primary schools in western Tajikistan. Parasites & Vectors. 2011;4:195. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan VR, Muliyil J. Mortality patterns and the effect of socioeconomic factors on mortality in rural Tamil Nadu, south India: a community-based cohort study. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103:801–806. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullan RL, Bethony JM, Geiger SM, et al. Human Helminth co-infection: analysis of spatial patterns and risk factors in a Brazilian community. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2008;4:e352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullan RL, Kabatereine NB, Quinnell RJ, Brooker S. Spatial and genetic epidemiology of Hookworm in a rural community in Uganda. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4:e731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VG, Aggrawal MC, Yadav R, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections, anemia and undernutrition among tribal adolescents of Madhya Pradesh. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2005;28:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rao VG, Sugunan AP, Murhekar MV, Sehgal SC. Malnutrition and high childhood mortality among the Onge tribe of the Andaman and Nicobar Island. Public Health Nutrition. 2006;9:19–25. doi: 10.1079/phn2005761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saathoff E, Olsen A, Sharp B, Kvalsvig JD, Appleton CC, Kleinschmidt I. American Journal of Tropical Medicine. Ecologic covariates of hookworm infection and reinfection in rural Kwazulu-natal/South Africa: a geographic information system-based study. 2005;72:384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad GA, Nawaunsk TA, Kochar V. Human Ecology and the Distribution and Abundance of Hookworm Populations. In: Croll NA, Cross JH, editors. Human Ecology and Infectious Diseases. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 187–223. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Montresor A, Engels D, Savioli L. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. Trends in Parasitology. 2003;19:547–551. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen E, Ismail M, Amarasinghe DK, Hettiarachchi I, Das-senaieke TS. The prevalence and control of soil-transmitted nematode infections among children and women in the plantations in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Medical Journal. 1996;41:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza EA, Da Silva-Nunes M, Malafronte RS, Muniz PT, Cardoso MA, Ferreira MU. Prevalence and spatial distribution of intestinal parasitic infections in a rural Amazonian settlement, Acre State, Brazil. Cademos De Saúde Pública. 2007;23:427–434. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugunan AP, Murhekar MV, Sehgal SC. Intestinal parasitic infestation among different population groups of Andaman and Nicobar islands. The Journal of Communicable Diseases. 1996;28:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utzinger J, Muller I, Vounatsou P, Singer BH, N’Goran EK, Tanner M. Random spatial distribution of Schistosoma mansoni and hookworm infections among school children within a single village. Journal of Parasitology. 2003;89:686–692. doi: 10.1645/GE-75R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The Fifty-fourth World Health Assembly, Fifth Report of Committee A: Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth infections. Geneva: WHO; 2001. [accessed 22 November 2012]. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA54/ea5451.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO I PCT databank. WHO; 2012a. [accessed 22 November 2012]. Available at: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/preventive_chemotherapy/sth/en/ [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO I Soil-transmitted helminths. WHO; 2012b. [accessed 22 November 2012]. Available at: http://www.who.int/intestinal_worms/en/ [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO plans major scale-up of interventions for soil-transmitted helminthiases (intestinal worms) WHO; 2012c. [accessed 22 November 2012]. Available at: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/STH_scale_up_2012/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelbauer K, Speich B, Mäusezahl M, Bos R, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Effect of Sanitation on soil-transmitted helminth infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medcine. 2012;9:el001162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]