Abstract

Background

Temperature sensitive lethal (tsl) mutants of the tephritid C. capitata are used extensively in control programs involving sterile insect technique in California. These flies are artificially reared and treated with ionizing radiation to render males sterile for further release en masse into the field to compete with wild males and disrupt establishment of invasive populations. Recent research suggests establishment of C. capitata in California, despite the fact that over 250 million sterile flies are released weekly as part of the state’s preventative program. In this project, genome-level quality assessment was performed, measured as expression differences between the Vienna-7 tsl mutants used in SIT programs and wild flies. RNA-seq was performed to provide a genome-wide map of the messenger RNA populations in C. capitata, and to investigate significant expression changes in Vienna-7 mass reared flies.

Results

Flies from the Vienna-7 colony showed a markedly reduced abundance of transcripts related to visual and chemical responses, including light stimuli, neural development and signaling pathways when compared to wild flies. In addition, genes associated with muscle development and locomotion were shown to be reduced. This suggests that the Vienna-7 line may be less competitive in mating and host plant finding where these stimuli are utilized. Irradiated flies showed several transcripts representing stress associated with irradiation.

Conclusions

There are significant changes at the transcriptome level that likely alter the competitiveness of mass reared flies and provide justification for pursuing methods for strain improvement, increasing competitiveness of mass-reared flies, or exploring alternative SIT approaches to increase the efficiency of eradication programs.

Keywords: Medfly, Ceratitis capitata, RNA-seq, Sterile insect technique, Irradiation, Sterilization

Background

The Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) is a polyphagous insect of great economic importance. Native to Africa, this fly is now distributed worldwide, with established populations in southern Europe, the Mediterranean region, Africa, Australia and some South American countries [1]. C. capitata was introduced to Hawaii in 1907 and considered established by 1910 [2,3]. It represents a major and ongoing threat to the continental United States, particularly in the agriculturally rich regions of Florida and California. Each year, detections of C. capitata are made, and efforts are ongoing to eliminate invasive populations in order to prevent further establishment and spread in the mainland. For example, each week, over 250 million sterile male mass reared flies are released in California to disrupt establishment of invasive populations. Despite this effort, a recent analysis of historical capture patterns suggested that C. capitata, along with other tephritid pests, is already established in California [4]. Establishment of C. capitata in areas despite mass reared sterile males release suggests a weakness or failure of this approach, possibly rooted in the quality of the mass reared flies.

The sterile insect technique (SIT) is a very important and useful tool for the control of the Mediterranean fruit fly. It makes use of laboratory reared sterile males which are released in large numbers to compete with wild invasive males for fertilizing females. In rearing flies for SIT programs, the presence of females in release colonies is undesirable as it reduces the number of males that can be reared from a set amount of diet. Additionally, release of female flies along with sterile males would confound the SIT approach through additional fruit damage caused by oviposition, and through competition with wild females for mating with the sterilized male flies [5-7]. For these reasons, to improve the efficiency and reduce the cost of SIT implementation, several genetic sexing strains (GSS) were developed that allow for the selection or elimination of females early in the rearing process. GSS traits include pupal color, differential development time, and temperature sensitivity [6]. Current GSS systems in C. capitata are based on a translocation that links the selectable trait with the Y sex chromosome. Among these GSS, the temperature sensitive lethal mutants (tsl) allow for the elimination of female eggs through incubation at elevated temperature. The tsl trait is often linked with a white pupal trait (wp), which allows for straightforward visual confirmation of presence of the trait during the pupal stage. Mutants carrying these traits have been developed by researchers at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna Austria (IAEA) and thus the C. capitata tsl strains are named “Vienna”; several independent lines have been developed from independent transformation events, with newer lines attempting to reduce trait breakdown by creating breakpoints closer to the sexing traits (e.g. Vienna-7 and Vienna-8) [5,8].

An important factor that determines the success of SIT is the competitiveness of the mass-reared sterile males with the wild males. Sterilization of males is achieved by gamma-irradiation in doses up to 145 Gy (http://www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/pdep/prpinfo). Irradiated males are known to be at a mating disadvantage in terms of attractiveness to wild females, courtship behavior, or acceptance of the courtship by females [9,10]. The process of irradiating flies may not only render fly males sterile, but ionizing radiation may potentially cause multiple unknown mutations in the genome. Additional disadvantages in fly quality can arise from long term inbreeding of colonies reared on highly artificial environments [11]. Insects growing in captivity for several generations would likely adapt to confinement conditions and experience inbreeding depression through changes in the frequencies and allele state of mutations present in the population, reducing the genetic diversity and fitness in the wild [12-14]. Other factors such as shipping to the target program location and handling of irradiated pupae may also reduce the quality of flies.

Together, these factors bring to question the overall efficiency of mass-reared SIT flies, and demonstrate the importance of investigating differences between mass reared flies and their wild counterparts from alternative perspectives. By cataloguing and quantitatively assessing these differences at the genome and transcriptome levels, measurable change can be determined, helping to understand why mass reared flies may be outperformed in the wild. In the present work the transcriptome of C. capitata was constructed from adult and pupal males, and the transcript expression profiles were compared between a wild C. capitata strain found in Hawaii and the mass-reared GSS Vienna-7 utilized in the Mediterranean Fruit Fly Exclusion Program by the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA), reared in their facility in Waimanalo, Hawaii. Analyses were done with the aim of providing a basic landscape of C. capitata transcriptome, as well as to shed light on the effects of long term mass rearing of the Vienna-7 line, as well as effects of gamma-irradiation. The hypothesis is that through long-term mass rearing, selection, and irradiation, there will be consistent changes in expression patterns in Vienna-7 derived flies that are indicative of reduced quality of these flies when compared to their wild counterparts. Overall, comparative analysis of expression and genetic changes that arise through mass rearing will provide insight into developing more competitive mass reared flies in SIT programs.

Results

Sequencing and quality filtering

For RNA-seq analysis, approximately 190 million paired 76 bp reads were obtained from Illumina Hiseq 2000 sequencing, totaling over 28 Gb of data (Table 1). These reads were evenly distributed between all of the libraries sequenced. All raw reads were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers SAMN02208095 – SAMN02208112 associated with BioProject PRJNA208956. From 190,186,205 raw read pairs, filtering and normalization reduced the read abundance to 17,217,414 (9.05%) reads used as input into the Trinity assembly, greatly reducing the computational requirements for assembly and avoiding complicating de Bruijn graphs with low quality or overabundant sequences.

Table 1.

Number of raw reads obtained from samples obtained from the Illumina GAIIx sequencing

| Sample | Rep | Number of raw read pairs | Number of reads mapped to filtered transcriptome (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna7 adults, γ-irradiated |

1 |

13,192,327 |

6,136,921 (46.52) |

| Vienna7 adults, γ-irradiated |

2 |

9,595,143 |

5,075,214 (52.89) |

| Vienna7 adults, γ-irradiated |

3 |

11,360,677 |

5,236,787 (46.10) |

| Vienna7 pupae, γ-irradiated |

1 |

10,582,671 |

5,035,268 (47.58) |

| Vienna7 pupae, γ-irradiated |

2 |

9,548,323 |

4,830,945 (50.59) |

| Vienna7 pupae, γ-irradiated |

3 |

11,750,225 |

5,906,277 (50.27) |

| Vienna7 adults |

1 |

11,893,729 |

5,540,467 (46.58) |

| Vienna7 adults |

2 |

9,207,645 |

4,767,827 (51.78) |

| Vienna7 adults |

3 |

11,887,697 |

6,077,674 (51.13) |

| Vienna7 pupae |

1 |

13,700,496 |

7,150,689 (52.19) |

| Vienna7 pupae |

2 |

5,836,933 |

3,234,876 (55.42) |

| Vienna7 pupae |

3 |

4,698,850 |

2,473,191 (52.63) |

| Wild Hawaiian adults |

1 |

7,463,699 |

3,524,921 (47.23) |

| Wild Hawaiian adults |

2 |

10,915,724 |

4,983,183 (45.65) |

| Wild Hawaiian adults |

3 |

11,412,891 |

4,996,645 (43.78) |

| Wild Hawaiian pupae |

1 |

12,312,072 |

5,689,915 (46.21) |

| Wild Hawaiian pupae |

2 |

11,240,088 |

5,219,322 (46.43) |

| Wild Hawaiian pupae |

3 |

13,587,015 |

6,175,680 (45.45) |

| Total | 190,186,205 | 92,055,802 |

De novo transcriptome assembly, assembly filtering and gene prediction

The raw assembly of the C. capitata transcriptome was constructed using the Trinity assembly pipeline with all filtered reads from all eighteen libraries pooled into one dataset. This assembly yielded 190,958 contigs, with an N50 contig size of 2,686 bases, 64,803 contigs greater than 1000 bp, and a transcript sum of 236.1 Mb. While not all contigs produced by Trinity were likely to represent true transcripts in C. capitata, this contig set was used as a starting point for defining the transcriptome present in our sample. Filtering based off of read abundance and component isoform percentage removed 135,957 sequences, leaving 55,001 remaining. Further filtering through identification of likely coding sequence based on ORF prediction identified a total of 18,919 transcripts across 10,775 unigenes, with an N50 transcript size of 3,546 bp and transcript sum of 53.00 Mb. This filtered assembly is considered a high quality transcript set, and was used for downstream analysis.

Gene annotation

Transcripts and genes identified in the final filtered assembly were annotated using public databases as described in Methods. More than 90% of the translated transcripts had homologs in the Uniprot database (e value < 1.00E-5) (Table 2). The resulting annotated transcript sequences were submitted to NCBI as Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly SUB276938, under Bioproject (PRJNA208956).

Table 2.

Transcript and gene annotation summary

| From total, high-quality identified and retained transcripts (18,919) | From total, high-quality identified genes (10,775) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Proteins (Uniprot) |

17,402 |

9,814 |

|

Curated Proteins (UniRef) |

14,143 |

6,840 |

|

Protein families (Pfam) |

13,646 |

7,886 |

|

Signal Peptides (SignalP4.1) |

2,106 |

1,150 |

|

Transmembrane domains (TMHMM) |

4,598 |

2,005 |

|

eggNOG |

12,292 |

5,828 |

| GO | 13,648 | 6,552 |

Pfam abundance

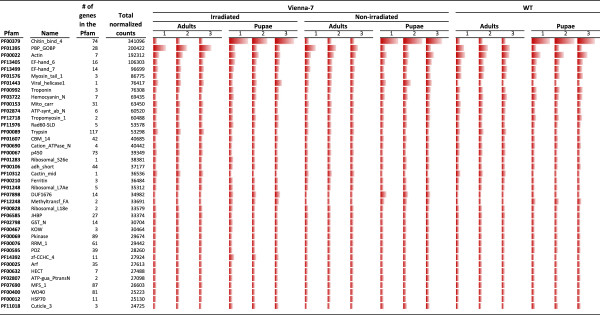

From the 10,776 unigenes identified in the assembly, 7,886 had a Pfam annotation based on translated sequence. These annotated genes belonged to one of 2,711 unique Pfam families. Forty six percent of these families could be placed into a Pfam Clan, for a total of 333 unique Pfam clans. The abundance of TMM normalized reads on each protein family was calculated to assess the global transcriptome composition (Additional file 1: Table S1). The protein family most abundant across unigenes was PF00089 (trypsins), followed by PF00069 (protein kinases). The protein family with the highest read counts was PF00379, annotated as chitin-binding proteins, representing structural proteins likely part of the insect cuticle; this family was over-represented in all pupae libraries of Vienna-7 and wild type. Interestingly, the second and fifth protein families with the highest read abundance corresponded to viral sequences: PF00910 (viral RNA helicases), and PF08762 (CRPV capsid protein-like family). These viral-related families showed very high counts in the Vienna-7 libraries as opposed to the wild type flies, making for up to 43% of the normalized counts in one of the irradiated libraries.

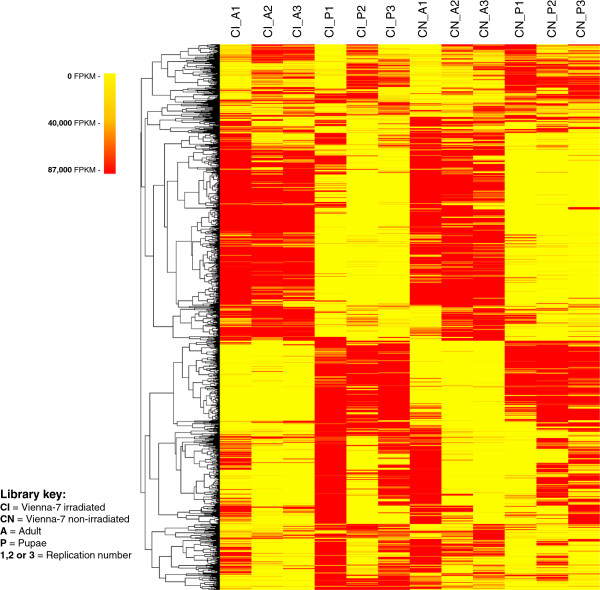

To better visualize the protein family makeup of the C. capitata transcriptome, the two top viral protein families were removed to overcome expression bias due to viral infection. Also, a family of peptidases (PF12381) with the sixth most abundant count numbers was removed as 98% of the counts were derived from a single library, clearly representing an outlier of a single replication. The absolute abundance of each of the top 40 Pfams is shown in Figure 1 together with the total of normalized counts for that family across all the libraries. The PBP_GOBP (PF01395), a family of olfactory receptors was the second most abundant family after chitin-binding proteins.

Figure 1.

Absolute abundance of unigenes across all libraries and total normalized counts on each library for the 40 Pfams with highest count values. The unigenes identified in the sequencing fell into one of 2,711 unique Pfam families. TMM normalized read counts on each protein family were calculated. Viral protein families were removed to overcome expression bias. Also, a family of peptidases (PF12381) with the sixth most abundant normalized count numbers was removed as 98% of the counts were derived from a single library, clearly representing an outlier of a single replication. Chitin binding proteins were the most abundant (PF 00379) followed by a family of olfactory receptors (PF01395).

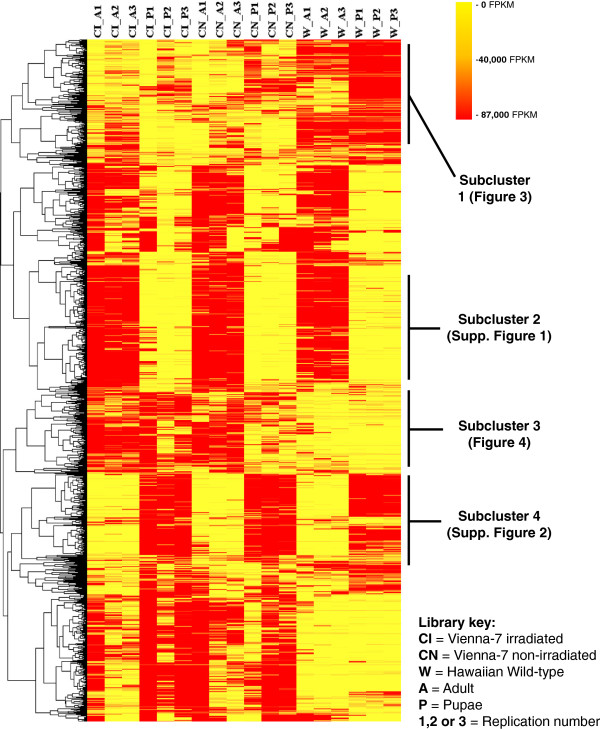

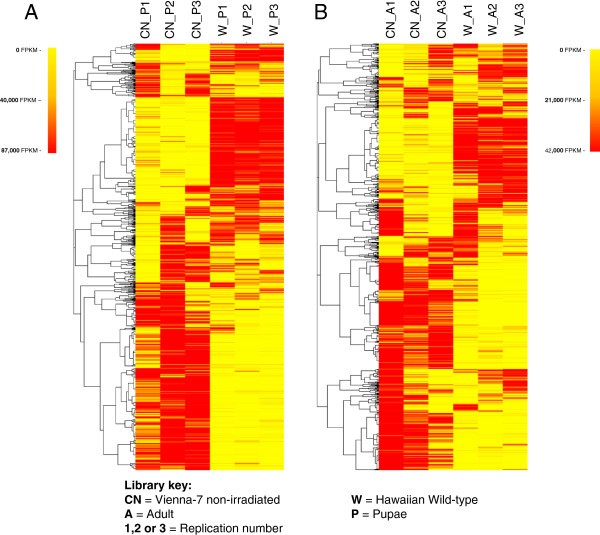

A cluster based on Spearman rank-based correlation coefficients was created to group similarly expressed protein families (Figure 2). The heatmap representing the clustering showed marked grouped differences between the wild Hawaiian colony and Vienna-7. Differences between adults and pupae were also visible and perhaps more abundant, these subclusters are shown in Figure 1. Derived subclusters with Pfam annotations are presented in Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2, Figures 3 and 4. A second clustering was run using only untreated flies from both the artificially reared colony and the wild Hawaiian population at either adult or pupal stage. These clusters show that at least 50% of the protein family composition differs in abundance between both types of flies at both stages tested (Figure 5a and b). Finally, irradiated and non-irradiated fly libraries (Vienna-7 flies only) were clustered together, using the same algorithm; most of the segregation was observed between the growing stages, while differences between irradiated and non-irradiated samples were minimal and mostly concentrated in the pupal stage (Figure 6). In addition, in this last clustering, we observed that the differences in protein family abundance between irradiated and non-irradiated samples were inconsistent across replication, pointing to the randomness of the irradiation effects on the genome.

Figure 2.

Heatmap showing the hierarchical clustering of the 2,711 identified Pfams across the 18 sequenced libraries. Clusters were constructed using Spearman rank-correlation coefficients on TMM-normalized counts on each of the libraries. Marked differences in normalized counts are shown between Vienna-7 and Hawaiian colonies and between developmental stages. Derived subclusters with Pfam annotations are in Additional file 2: Figures S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2, Figures 3 and 4. Derived subclusters with Pfam annotations are presented in Additional file 2: Figures S1 and Additional file 3: Figure S2, Figures 3 and 4.

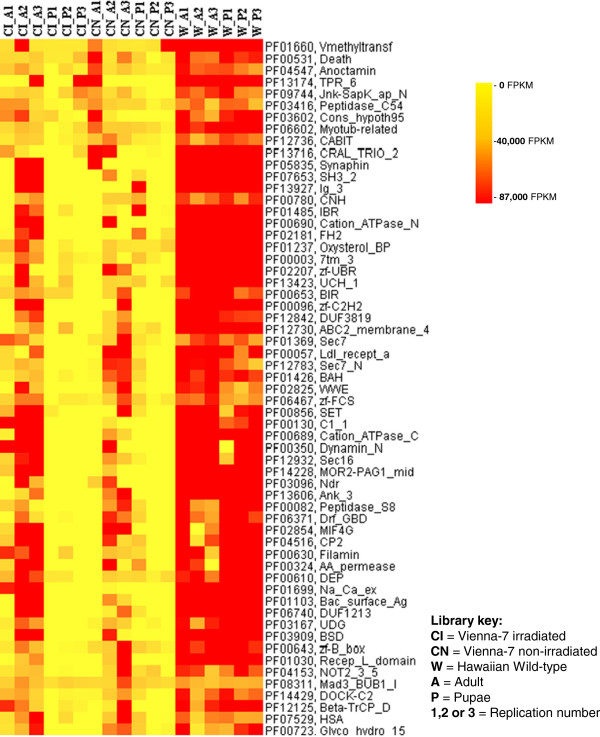

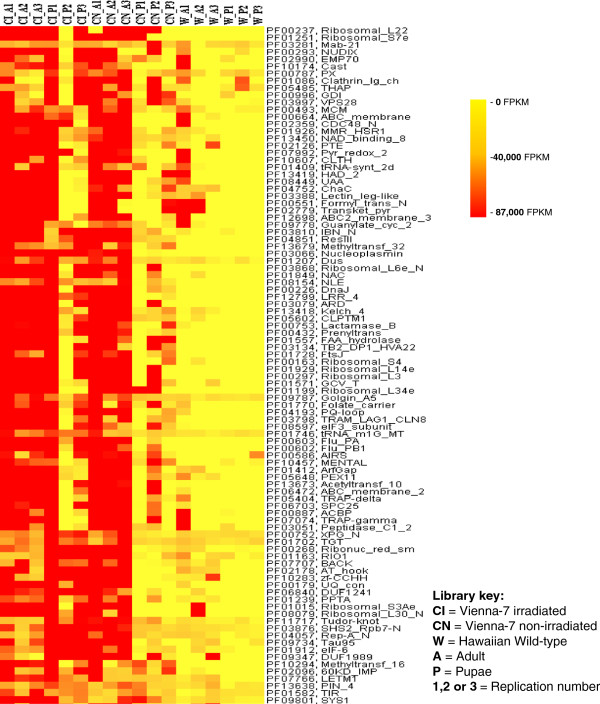

Figure 3.

Sub-cluster of identified Pfams derived from Figure 2. Differences between libraries of the Vienna-7 and the Hawaiian flies showing Pfams overrepresented in Wild Hawaiian flies.

Figure 4.

Sub-cluster of identified Pfams derived from Figure 2. Differences between libraries of the Vienna-7 and the Hawaiian flies showing Pfams overrepresented in the Vienna-7 libraries.

Figure 5.

Clustering of identified Pfams present on untreated flies from the artificially reared colony and the wild Hawaiian population. Figure 5a displays pupal stage and Figure 5b displays adult stage. At least 50% of the protein family composition differs in abundance between both types of flies at both stages tested.

Figure 6.

Clustering of identified Pfams in irradiated and non-irradiated fly libraries (Vienna-7 flies only); Most of the segregation was observed between the growing stages, while differences between irradiated and non-irradiated samples were minimal and mostly concentrated in the pupal stage.

Differential gene expression

Fold change

A statistically based measurement is necessary to identify the most potentially differentially regulated genes between repeated sequenced mRNA libraries. The overall differences between the two types of flies (Wild vs. Vienna-7), between adults and pupae, and between irradiated and non-irradiated flies from the Vienna-7 colony were tested. For these three effects a total of 5,619 unigenes were identified as statistically differentially regulated in at least one of the comparisons (FDR corrected p-value < 0.05). Not surprisingly, the comparison between adults and pupae yielded the highest number of differentially regulated transcripts (4,634 genes), followed by the comparison between the wild and Vienna-7 (968 genes). The comparison between irradiated and non-irradiated flies showed only 17 genes significantly differentially regulated. Additionally, six independent pair wise comparisons between replicated libraries were tested (Table 3); each of these yielded a range of differentially expressed genes, varying from 148 genes (Vienna-7 irradiated pupae vs. non-irradiated pupae) to over four thousand genes (wild adult vs. wild pupae).

Table 3.

Number of declared significantly differentially regulated genes in sample pairwise comparisons

| Comparison tested | # of significantly differentially regulated (FDR pval <0.05) |

|---|---|

| Vienna7 vs. Wild Hawaiian wild type (overall) |

968 |

| Adults vs pupae (overall) |

4,634 |

| Irradiated flies vs. non-irradiated flies |

17 |

| Wild Hawaiian adults vs. wild Hawaiian type pupae |

4,345 |

| Vienna7 adults vs. Vienna7 pupae |

3,360 |

| Vienna7 pupae vs. wild Hawaiian type pupae |

3,094 |

| Vienna7 adults vs. wild Hawaiian type adults |

1,694 |

| Vienna7 irradiated adults vs. Vienna7 non-irradiated adults |

364 |

| Vienna7 irradiated pupae vs. Vienna7 non-irradiated pupae | 148 |

Gene ontology term enrichment of differentially expressed genes

Gene Ontology (GO) classification coupled with term enrichment analysis was used to group statistically differentially regulated genes by biological function allowing for a better understanding of the biological differences between the flies used in the experiment. The term enrichment results for the comparison between adults and pupae showed highly significant enrichment on up-regulated genes with terms related to primary metabolism, including amino acid, carbohydrate, lipid and general anabolism and catabolism processes (e.g. GO:0044710, GO:0019752, GO:1901564, GO:1901605, GO:0044723, GO:0032787). Genes with down-regulation in the adults vs. pupae comparison (or with more abundance in pupae) showed very high term enrichment in cell adhesion processes (i.e. GO:0007155, GO:0022610, GO:0016337, GO:0007156, GO:0016339) and development including general anatomical, respiratory, and epithelium development (e.g. GO:0048856, GO:0007424, GO:0044767, GO:0060541, GO:0048731, GO:0030036, GO:0060429, GO:0048569). The top 40 up- and down- regulated GO terms are shown in Additional file 4: Table S2 with their respective expected values and significance p-values.

The term enrichment for the comparison between flies from the translocated Vienna-7 flies vs. wild-type flies showed an over-representation of nucleic acid processes in the artificially reared Vienna-7 (e.g. GO:0090304, GO:0006259, GO:0006139, GO:0090305, GO:0034660) Also, terms related to viral life cycle were present in this group (i.e. GO:0019079, GO:0019058 and GO:0019058). Signaling, sensory, and neurological-related processes were more abundant in the wild-type colony than in Vienna-7 (e.g. GO:0030182, GO:0050877, GO:0048699, GO:0007423, GO:0023052) (Table 4). To better understand the differences between colonies, GO term enrichment was also run on the list of significantly differentially regulated unigenes obtained from the separate pair wise comparison between Vienna-7 pupae only and wild pupae only (3,094 unigenes) and between Vienna-7 adults only and wild adults only (1,649 unigenes). Vienna-7 pupae compared to wild pupae showed several stress-related terms with higher abundance in the Vienna-7 flies, including response to cold (GO:0009409, GO:0009631), disease response (GO:0009617), and oxidative stress (increase in antioxidant machinery in response to reactive oxygen species originated by stress)-related terms (such as electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation: GO:0022900, GO:0022904, GO:0042773, GO:0006119, and GO:0042775). In addition, several viral-related terms were present, four of them in the top 40 most significant terms, with an additional “gene silencing” term (GO:0019079, GO:0019058, GO:0016032, GO:0022415, GO:0031047). Terms with less abundance in the Vienna-7 pupae than in the wild corresponded to those in signaling and neurological processes (e.g. GO:0007154, GO:0023052, GO:0044700, GO:0007165, GO:0050877) (Table 5). Comparing adults between both colonies showed more abundance of a vast amount of nucleic acid metabolism, DNA replication and cell cycle-related terms in the Vienna-7 colony (Table 6). Interestingly, the wild-type colony showed a distinctly high enrichment in terms related to response to light stimuli including phototransduction processes, rhodopsin signaling, detection of visible light and the like. A term related to perception of chemical stimulus was also found among the top highly significant GO terms, suggesting impact on both the visual and olfaction systems. This last comparison also showed higher abundance of motility-related terms in the wild fly compared to Vienna-7, these terms including muscle cell differentiation, striated muscle cell development and differentiation, locomotion and motility (Table 6).

Table 4.

Top 20 Vienna7 vs. wild Hawaiian type differentially regulated genes GO term enrichment

| Term | Annotated | Significant | Expected | Fisher exact test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Up-regulated genes

| |||||

| GO:1901360 |

Organic cyclic compound metabolic processes |

1289 |

130 |

81.06 |

6.70E-11 |

| GO:0090304 |

Nucleic acid metabolic process |

948 |

105 |

59.61 |

7.10E-11 |

| GO:0006259 |

DNA metabolic process |

239 |

42 |

15.03 |

3.50E-10 |

| GO:0006725 |

Cellular aromatic compound metabolism |

1231 |

123 |

77.41 |

7.40E-10 |

| GO:0006396 |

RNA processing |

166 |

33 |

10.44 |

1.30E-09 |

| GO:0006139 |

Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

1166 |

117 |

73.32 |

2.20E-09 |

| GO:0046483 |

Heterocycle metabolic process |

1212 |

120 |

76.21 |

2.80E-09 |

| GO:0044260 |

Cellular macromolecule metabolic process |

1441 |

135 |

90.61 |

5.50E-09 |

| GO:0090305 |

Nucleic acid phosphodiester bond hydroly… |

78 |

21 |

4.9 |

5.70E-09 |

| GO:0019079 |

Viral genome replication |

13 |

9 |

0.82 |

7.70E-09 |

| GO:0042254 |

Ribosome biogenesis |

60 |

18 |

3.77 |

1.10E-08 |

| GO:0034660 |

NcRNA metabolic process |

74 |

20 |

4.65 |

1.30E-08 |

| GO:0034641 |

Cellular nitrogen compound metabolic pro… |

1291 |

123 |

81.18 |

1.90E-08 |

| GO:0022613 |

Ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis |

73 |

19 |

4.59 |

5.70E-08 |

| GO:0006260 |

DNA replication |

93 |

21 |

5.85 |

1.60E-07 |

| GO:0044237 |

Cellular metabolic process |

2258 |

181 |

141.99 |

3.90E-07 |

| GO:0019058 |

Viral infectious cycle |

18 |

9 |

1.13 |

4.00E-07 |

| GO:0034470 |

NcRNA processing |

53 |

15 |

3.33 |

4.60E-07 |

| GO:0006807 |

Nitrogen compound metabolic process |

1455 |

128 |

91.49 |

1.30E-06 |

| GO:0006281 |

DNA repair |

82 |

17 |

5.16 |

8.90E-06 |

|

Down-regulated genes

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GO:0048468 |

Cell development |

610 |

94 |

42.38 |

1.30E-15 |

| GO:0048646 |

Anatomical structure formation |

662 |

95 |

45.99 |

9.90E-14 |

| GO:0051239 |

Regulation of multicellular organismal processes |

413 |

67 |

28.69 |

5.00E-12 |

| GO:0030182 |

Neuron differentiation |

331 |

58 |

23 |

7.30E-12 |

| GO:0003008 |

System process |

462 |

70 |

32.1 |

4.20E-11 |

| GO:0030154 |

Cell differentiation |

927 |

112 |

64.41 |

4.60E-11 |

| GO:0009653 |

Anatomical structure morphogenesis |

761 |

97 |

52.87 |

8.80E-11 |

| GO:0048869 |

Cellular developmental process |

964 |

114 |

66.98 |

1.20E-10 |

| GO:0050877 |

Neurological system process |

385 |

61 |

26.75 |

1.60E-10 |

| GO:0048699 |

Generation of neurons |

356 |

58 |

24.73 |

1.60E-10 |

| GO:0007267 |

Cell-cell signaling |

264 |

48 |

18.34 |

1.70E-10 |

| GO:0044767 |

Single-organism developmental process |

1185 |

131 |

82.33 |

2.40E-10 |

| GO:0048513 |

Organ development |

697 |

90 |

48.43 |

2.90E-10 |

| GO:0007423 |

Sensory organ development |

191 |

39 |

13.27 |

3.20E-10 |

| GO:0023052 |

Signaling |

980 |

114 |

68.09 |

3.50E-10 |

| GO:0044700 |

Single organism signaling |

980 |

114 |

68.09 |

3.50E-10 |

| GO:0048749 |

Compound eye development |

122 |

30 |

8.48 |

3.90E-10 |

| GO:0044707 |

Single-multicellular organism process |

1699 |

169 |

118.04 |

4.10E-10 |

| GO:0007154 |

Cell communication |

996 |

115 |

69.2 |

4.50E-10 |

| GO:0042692 | Muscle cell differentiation | 123 | 30 | 8.55 | 4.80E-10 |

Table 5.

Vienna7 pupae vs. wild Hawaiian wild-type pupae differentially regulated genes GO term enrichment

| Term | Annotated | Significant | Expected | Fisher exact test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Up-regulated genes

| |||||

| GO:0006412 |

Translation |

103 |

45 |

20.64 |

2.90E-08 |

| GO:0022900 |

Electron transport chain |

48 |

24 |

9.62 |

3.00E-06 |

| GO:0019079 |

Viral genome replication |

13 |

10 |

2.61 |

1.60E-05 |

| GO:0009409 |

Response to cold |

8 |

7 |

1.6 |

8.40E-05 |

| GO:0019058 |

Viral infectious cycle |

18 |

11 |

3.61 |

0.00016 |

| GO:0006091 |

Generation of precursor metabolites |

117 |

40 |

23.45 |

0.0002 |

| GO:0009631 |

Cold acclimation |

5 |

5 |

1 |

0.00032 |

| GO:0022904 |

Respiratory electron transport chain |

12 |

8 |

2.41 |

0.00058 |

| GO:0006626 |

Protein targeting to mitochondrion |

10 |

7 |

2 |

0.00086 |

| GO:0070585 |

Protein localization to mitochondrion |

10 |

7 |

2 |

0.00086 |

| GO:0072655 |

Establishment of protein localization |

10 |

7 |

2 |

0.00086 |

| GO:0065004 |

Protein-DNA complex assembly |

27 |

13 |

5.41 |

0.00093 |

| GO:0042773 |

ATP synthesis coupled electron transport |

8 |

6 |

1.6 |

0.00123 |

| GO:0042775 |

Mitochondrial ATP coupled electron transport |

8 |

6 |

1.6 |

0.00123 |

| GO:0044237 |

Vellular metabolic process |

2258 |

492 |

452.56 |

0.00136 |

| GO:0016032 |

Viral reproduction |

39 |

16 |

7.82 |

0.00211 |

| GO:0044764 |

Multi-organism cellular process |

39 |

16 |

7.82 |

0.00211 |

| GO:0008152 |

Metabolic process |

2745 |

586 |

550.16 |

0.00217 |

| GO:0016125 |

Sterol metabolic process |

36 |

15 |

7.22 |

0.0024 |

| GO:0007017 |

Microtubule-based process |

186 |

53 |

37.28 |

0.00298 |

| GO:0006119 |

Oxidative phosphorylation |

9 |

6 |

1.8 |

0.00307 |

| GO:0006767 |

Water-soluble vitamin metabolic process |

9 |

6 |

1.8 |

0.00307 |

| GO:0034660 |

NcRNA metabolic process |

74 |

25 |

14.83 |

0.00365 |

| GO:0006839 |

Mitochondrial transport |

21 |

10 |

4.21 |

0.00405 |

| GO:0006457 |

Protein folding |

52 |

19 |

10.42 |

0.00407 |

| GO:0042254 |

Ribosome biogenesis |

60 |

21 |

12.03 |

0.00467 |

| GO:0042982 |

Amyloid precursor protein metabolism |

7 |

5 |

1.4 |

0.00468 |

| GO:0045940 |

Positive regulation of steroid metabolism |

7 |

5 |

1.4 |

0.00468 |

| GO:0031047 |

Gene silencing by RNA |

28 |

12 |

5.61 |

0.00491 |

| GO:0015931 |

Nucleobase-containing compound transport |

53 |

19 |

10.62 |

0.00518 |

| GO:0009617 |

Response to bacterium |

72 |

24 |

14.43 |

0.00528 |

| GO:0044267 |

Cellular protein metabolic process |

609 |

146 |

122.06 |

0.00579 |

| GO:0000226 |

Microtubule cytoskeleton organization |

137 |

40 |

27.46 |

0.00594 |

| GO:0022415 |

Viral reproductive process |

32 |

13 |

6.41 |

0.00598 |

| GO:0007379 |

Segment specification |

22 |

10 |

4.41 |

0.00611 |

| GO:0008202 |

Steroid metabolic process |

54 |

19 |

10.82 |

0.00653 |

| GO:0001666 |

Response to hypoxia |

43 |

16 |

8.62 |

0.00663 |

| GO:0006379 |

mRNA cleavage |

5 |

4 |

1 |

0.00674 |

| GO:0034433 |

Steroid esterification |

5 |

4 |

1 |

0.00674 |

| GO:0034434 |

Sterol esterification |

5 |

4 |

1 |

0.00674 |

|

Down-regulated genes

| |||||

| GO:0065007 |

Biological regulation |

1938 |

577 |

429.5 |

5.50E-28 |

| GO:0050794 |

Regulation of cellular process |

1625 |

503 |

360.13 |

4.80E-27 |

| GO:0007154 |

Cell communication |

996 |

346 |

220.73 |

4.00E-26 |

| GO:0023052 |

Signaling |

980 |

341 |

217.19 |

8.30E-26 |

| GO:0044700 |

Single organism signaling |

980 |

341 |

217.19 |

8.30E-26 |

| GO:0050789 |

Regulation of biological process |

1780 |

533 |

394.48 |

4.40E-25 |

| GO:0003008 |

System process |

462 |

185 |

102.39 |

2.30E-20 |

| GO:0048646 |

Anatomical structure formation |

662 |

240 |

146.71 |

9.10E-20 |

| GO:0044699 |

Single-organism process |

2913 |

755 |

645.58 |

1.90E-19 |

| GO:0044763 |

Single-organism cellular process |

2412 |

653 |

534.55 |

2.50E-19 |

| GO:0009653 |

Anatomical structure morphogenesis |

761 |

265 |

168.65 |

3.80E-19 |

| GO:0050877 |

Neurological system process |

385 |

158 |

85.32 |

1.50E-18 |

| GO:0048468 |

Cell development |

610 |

222 |

135.19 |

2.20E-18 |

| GO:0007165 |

Signal transduction |

804 |

274 |

178.18 |

2.40E-18 |

| GO:0044707 |

Single-multicellular organism process |

1699 |

491 |

376.53 |

7.30E-18 |

| GO:0044767 |

Single-organism developmental process |

1185 |

369 |

262.62 |

7.60E-18 |

| GO:0030182 |

Neuron differentiation |

331 |

140 |

73.36 |

8.60E-18 |

| GO:0032501 |

Multicellular organismal process |

1737 |

497 |

384.95 |

4.10E-17 |

| GO:0048513 |

Organ development |

697 |

242 |

154.47 |

4.10E-17 |

| GO:0010646 |

Regulation of cell communication |

412 |

161 |

91.31 |

1.90E-16 |

| GO:0035556 |

Intracellular signal transduction |

359 |

145 |

79.56 |

2.90E-16 |

| GO:0048731 |

System development |

1025 |

324 |

227.16 |

2.90E-16 |

| GO:0023051 |

Regulation of signaling |

417 |

162 |

92.42 |

2.90E-16 |

| GO:0048699 |

Generation of neurons |

356 |

144 |

78.9 |

3.20E-16 |

| GO:0007267 |

Cell-cell signaling |

264 |

115 |

58.51 |

8.30E-16 |

| GO:0007268 |

Synaptic transmission |

181 |

88 |

40.11 |

9.20E-16 |

| GO:0048856 |

Anatomical structure development |

1301 |

389 |

288.33 |

1.60E-15 |

| GO:0009887 |

Organ morphogenesis |

316 |

130 |

70.03 |

2.30E-15 |

| GO:0032989 |

Cellular component morphogenesis |

362 |

143 |

80.23 |

4.50E-15 |

| GO:0016043 |

Cellular component organization |

1160 |

353 |

257.08 |

4.90E-15 |

| GO:0050793 |

Regulation of developmental process |

339 |

135 |

75.13 |

1.40E-14 |

| GO:0007275 |

Multicellular organismal development |

1356 |

398 |

300.52 |

1.90E-14 |

| GO:0030154 |

Cell differentiation |

927 |

292 |

205.44 |

3.70E-14 |

| GO:0035637 |

Multicellular organismal signaling |

206 |

93 |

45.65 |

4.60E-14 |

| GO:0019226 |

Transmission of nerve impulse |

203 |

92 |

44.99 |

4.70E-14 |

| GO:0000904 |

Cell morphogenesis involved in different… |

249 |

106 |

55.18 |

8.40E-14 |

| GO:0009966 |

Regulation of signal transduction |

363 |

140 |

80.45 |

9.10E-14 |

| GO:0007399 |

Nervous system development |

617 |

210 |

136.74 |

1.20E-13 |

| GO:0048666 |

Neuron development |

294 |

119 |

65.16 |

1.70E-13 |

| GO:0000902 |

Cell morphogenesis |

315 |

125 |

69.81 |

2.10E-13 |

| GO:0048869 | Cellular developmental process | 964 | 298 | 213.64 | 3.00E-13 |

Table 6.

Vienna7 adults vs. wild Hawaiian wild-type adults differentially regulated genes GO term enrichment

| Term | Annotated | Significant | Expected | Fisher exact test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Up-regulated genes

| |||||

| GO:0044260 |

Cellular macromolecule metabolic process |

1441 |

270 |

190.73 |

7.90E-14 |

| GO:0006396 |

RNA processing |

166 |

56 |

21.97 |

3.50E-12 |

| GO:0044237 |

Cellular metabolic process |

2258 |

372 |

298.87 |

1.40E-11 |

| GO:0022613 |

Ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis |

73 |

31 |

9.66 |

4.60E-10 |

| GO:0043170 |

Macromolecule metabolic process |

1839 |

311 |

243.41 |

5.20E-10 |

| GO:0008152 |

Metabolic process |

2745 |

425 |

363.33 |

1.40E-09 |

| GO:0034660 |

ncRNA metabolic process |

74 |

30 |

9.79 |

3.40E-09 |

| GO:0071704 |

Organic substance metabolic process |

2587 |

403 |

342.41 |

6.90E-09 |

| GO:0042254 |

Ribosome biogenesis |

60 |

26 |

7.94 |

7.30E-09 |

| GO:0006364 |

rRNA processing |

35 |

19 |

4.63 |

8.00E-09 |

| GO:0034470 |

ncRNA processing |

53 |

24 |

7.02 |

9.60E-09 |

| GO:0016072 |

rRNA metabolic process |

36 |

19 |

4.76 |

1.50E-08 |

| GO:0044238 |

Primary metabolic process |

2432 |

382 |

321.9 |

1.70E-08 |

| GO:0090304 |

Nucleic acid metabolic process |

948 |

175 |

125.48 |

1.20E-07 |

| GO:0006457 |

Protein folding |

52 |

22 |

6.88 |

1.80E-07 |

| GO:0034641 |

Cellular nitrogen compound metabolism |

1291 |

221 |

170.88 |

8.10E-07 |

| GO:0046483 |

Heterocycle metabolic process |

1212 |

209 |

160.42 |

1.20E-06 |

| GO:0006725 |

Cellular aromatic compound metabolism |

1231 |

211 |

162.93 |

1.60E-06 |

| GO:0006139 |

Nucleobase-containing compound metabolism |

1166 |

201 |

154.33 |

2.30E-06 |

| GO:0044267 |

Cellular protein metabolic process |

609 |

118 |

80.61 |

2.50E-06 |

| GO:1901360 |

Organic cyclic compound metabolism |

1289 |

218 |

170.61 |

2.90E-06 |

| GO:0006974 |

Response to DNA damage stimulus |

136 |

38 |

18 |

3.00E-06 |

| GO:0000075 |

Cell cycle checkpoint |

44 |

18 |

5.82 |

4.30E-06 |

| GO:0031570 |

DNA integrity checkpoint |

33 |

15 |

4.37 |

5.80E-06 |

| GO:0030163 |

Protein catabolic process |

110 |

32 |

14.56 |

7.30E-06 |

| GO:0044265 |

Cellular macromolecule catabolic process |

143 |

38 |

18.93 |

1.10E-05 |

| GO:0071156 |

Regulation of cell cycle arrest |

47 |

18 |

6.22 |

1.30E-05 |

| GO:0000077 |

DNA damage checkpoint |

28 |

13 |

3.71 |

1.90E-05 |

| GO:0009451 |

RNA modification |

18 |

10 |

2.38 |

2.50E-05 |

| GO:0007050 |

Cell cycle arrest |

58 |

20 |

7.68 |

2.70E-05 |

| GO:0016071 |

mRNA metabolic process |

122 |

33 |

16.15 |

2.80E-05 |

| GO:0051603 |

Proteolysis involved in cellular protein… |

88 |

26 |

11.65 |

4.00E-05 |

| GO:0006807 |

Nitrogen compound metabolic process |

1455 |

234 |

192.58 |

5.70E-05 |

| GO:0006270 |

DNA replication initiation |

10 |

7 |

1.32 |

5.70E-05 |

| GO:0044257 |

Cellular protein catabolic process |

90 |

26 |

11.91 |

6.10E-05 |

| GO:0019079 |

Viral genome replication |

13 |

8 |

1.72 |

6.30E-05 |

| GO:0007093 |

Mitotic cell cycle checkpoint |

31 |

13 |

4.1 |

7.00E-05 |

| GO:0022403 |

Cell cycle phase |

246 |

54 |

32.56 |

7.10E-05 |

| GO:0009057 |

Macromolecule catabolic process |

201 |

46 |

26.6 |

8.70E-05 |

| GO:0010389 |

Regulation of G2/M transition of mitotic… |

28 |

12 |

3.71 |

0.0001 |

| GO:0051329 |

Interphase of mitotic cell cycle |

73 |

22 |

9.66 |

0.00011 |

|

Down-regulated genes

| |||||

| GO:0071482 |

Cellular response to light stimulus |

14 |

11 |

1.59 |

9.80E-09 |

| GO:0007603 |

Phototransduction, visible light |

10 |

9 |

1.14 |

2.70E-08 |

| GO:0016056 |

Rhodopsin mediated signaling pathway |

10 |

9 |

1.14 |

2.70E-08 |

| GO:0048646 |

Anatomical structure formation involved… |

662 |

118 |

75.31 |

4.80E-08 |

| GO:0007600 |

Sensory perception |

142 |

39 |

16.15 |

6.40E-08 |

| GO:0009583 |

Detection of light stimulus |

29 |

15 |

3.3 |

9.60E-08 |

| GO:0009584 |

Detection of visible light |

19 |

12 |

2.16 |

9.80E-08 |

| GO:0042692 |

Muscle cell differentiation |

123 |

35 |

13.99 |

1.20E-07 |

| GO:0001539 |

Ciliary or flagellar motility |

11 |

9 |

1.25 |

1.30E-07 |

| GO:0051239 |

Regulation of multicellular organismal processes |

413 |

81 |

46.98 |

1.70E-07 |

| GO:0003008 |

System process |

462 |

88 |

52.55 |

1.90E-07 |

| GO:0009581 |

Detection of external stimulus |

38 |

17 |

4.32 |

2.00E-07 |

| GO:0016059 |

Deactivation of rhodopsin mediated signa… |

9 |

8 |

1.02 |

2.20E-07 |

| GO:0022400 |

Regulation of rhodopsin mediated signali… |

9 |

8 |

1.02 |

2.20E-07 |

| GO:0009582 |

Detection of abiotic stimulus |

39 |

17 |

4.44 |

3.20E-07 |

| GO:0055002 |

Striated muscle cell development |

86 |

27 |

9.78 |

4.00E-07 |

| GO:0007602 |

Phototransduction |

21 |

12 |

2.39 |

4.60E-07 |

| GO:0055001 |

Muscle cell development |

92 |

28 |

10.47 |

5.00E-07 |

| GO:0030239 |

Myofibril assembly |

36 |

16 |

4.1 |

5.10E-07 |

| GO:0061061 |

Muscle structure development |

174 |

42 |

19.79 |

9.80E-07 |

| GO:0050953 |

Sensory perception of light stimulus |

70 |

23 |

7.96 |

1.20E-06 |

| GO:0051606 |

Setection of stimulus |

48 |

18 |

5.46 |

2.10E-06 |

| GO:0071478 |

Cellular response to radiation |

20 |

11 |

2.28 |

2.40E-06 |

| GO:0007018 |

Microtubule-based movement |

53 |

19 |

6.03 |

2.40E-06 |

| GO:0007601 |

Visual perception |

68 |

22 |

7.74 |

2.80E-06 |

| GO:0050877 |

Neurological system process |

385 |

73 |

43.8 |

3.00E-06 |

| GO:0048468 |

Cell development |

610 |

104 |

69.39 |

3.70E-06 |

| GO:0009653 |

Anatomical structure morphogenesis |

761 |

124 |

86.57 |

3.80E-06 |

| GO:0044707 |

Single-multicellular organism process |

1699 |

239 |

193.27 |

4.80E-06 |

| GO:0051146 |

Striated muscle cell differentiation |

108 |

29 |

12.29 |

5.40E-06 |

| GO:0030182 |

Neuron differentiation |

331 |

64 |

37.65 |

6.90E-06 |

| GO:0032501 |

Multicellular organismal process |

1737 |

242 |

197.59 |

9.10E-06 |

| GO:0031032 |

Actomyosin structure organization |

44 |

16 |

5.01 |

1.20E-05 |

| GO:0040011 |

Locomotion |

380 |

70 |

43.23 |

1.40E-05 |

| GO:0009416 |

Response to light stimulus |

55 |

18 |

6.26 |

1.90E-05 |

| GO:0032101 |

Regulation of response to external stimuli |

55 |

18 |

6.26 |

1.90E-05 |

| GO:0071214 |

Cellular response to abiotic stimulus |

28 |

12 |

3.19 |

2.20E-05 |

| GO:0007606 |

Sensory perception of chemical stimulus |

56 |

18 |

6.37 |

2.50E-05 |

| GO:0032989 |

Cellular component morphogenesis |

362 |

66 |

41.18 |

3.70E-05 |

| GO:0048699 |

generation of neurons |

356 |

65 |

40.5 |

4.10E-05 |

| GO:2000026 | Regulation of multicellular organismal development | 228 | 46 | 25.94 | 5.10E-05 |

The term enrichment for the overall comparison between irradiated and non-irradiated samples in the Vienna-7 colony showed high significance for terms related to hormonal synthesis and related compounds in up-regulated genes (i.e. GO:0016126, GO:0008299, GO:0006694), suggesting an increased activity of these pathways as a result of irradiation. On the other hand, genes with higher expression values in the non-irradiated samples resulted in a term enrichment of high significance for several viral-related terms (e.g. GO:0019058, GO:0022415, GO:0016032, GO:0)006278 (Additional file 5: Table S3). Because of our special interest in the effects of irradiation on the Vienna-7 colony, the differential expression between irradiated and non-irradiated samples from adults and pupa were separated and the GO term enrichment for these pairwise sample comparisons were analyzed. Terms related to virus/transposon sequences were found enriched only in the down-regulated irradiated vs. non irradiated pupae dataset, suggesting that irradiation somehow affects the presence of virus or transposon mobility in the Vienna-7 colony, but only when applied to pupae. Additionally, two GO terms related to reproduction were among the top 20 found down-regulated in pupae irradiated vs. non-irradiated flies (i.e. GO:0022414 and GO:0000003), perhaps pointing to the desired sterilization results expected from the treatment (Additional file 6: Table S4). Up-regulated terms in irradiated vs. non irradiated pupae samples were highly enriched for DNA repair-related mechanism (e.g. GO:0006974, GO:0006281, GO:0006302), suggesting DNA damage (Additional file 6: Table S4). In adults, irradiation effects seemed to be very random, with biological processes affected ranging from ion transport to amino acids metabolism (Additional file 7: Table S5).

Discussion

Whole transcriptome analyses are of growing importance for the understanding of biological processes that take place in organisms of interest. We have generated a de novo transcriptome assembly of the pupal and adult stages of male Mediterranean fruit fly, C. capitata, using paired-end RNA-seq analysis. The assembly identified 18,919 transcripts and 10,775 unigenes which were annotated and used for a descriptive and comparative analysis of the mRNA composition of Hawaiian wild flies and mass reared GSS Vienna-7 flies at adult and pupae stages, before and after ionizing radiation treatment. With the data, we were able to delineate a general protein family-based composition of C. capitata, as well as identify specific genes and protein families present in specific libraries. In addition, we have built and made public extensive data obtained from the sequencing. This data can be used for generation of new hypotheses regarding different aspects on the biology of this important pest as well as a resource for developing assays for assessing the quality of mass reared flies.

Differences between adults and pupae across both types of flies showed that several developmental processes were significantly overrepresented in pupae as compared to the adult. Also, the four most significantly enriched GO terms were related to cell adhesion, a process which is known to play a key role in development and tissue morphogenesis [15,16]. While these results are not surprising, they provide a means of verification on the quality of the experiment and the data analysis performed.

Grouping absolute expression values by Pfam and clustering the data, we noted considerable differences between the artificially reared colonies and the wild Hawaiian flies. Furthermore, by contrasting the Vienna-7 with the Hawaiian wild flies’ relative transcript levels and statistical significance, we have identified the presence of several viral-related sequences among the sequenced transcripts, which suggests the existence of a virus in the mass reared colony; this is supported by the occurrence of several stress-related transcripts. Preliminary analyses showed that these sequences may belong to a picornavirus; however, it is possible that these transcripts are an indication of increased or activated transposon activity in the Vienna-7 colony. That the possible presence of virus is detrimental for the quality of the reared colonies needs to be tested, as several endogenous viruses have been found in different strains of C. capitata and are commonly found in other fruit flies [17-19]. Nonetheless, this is an interesting point to investigate and simple measures could be employed to monitor viral levels in mass reared colonies and measures put forth to reduce the impact of virus on fly quality. Additionally, by comparing the Vienna-7 colony to wild pupae and adults, the differential expression analyses showed marked down-regulation of signaling and neurological processes. In adults, two important sensory mechanisms were observed to be down-regulated in the Vienna-7 flies: light response processes and chemoreception. A third marked difference was observed in genes related to muscle development, muscle differentiation and locomotion, which were also reduced in abundance in the Vienna-7 colonies compared to the wild Hawaiian flies. Given the number and consistency of GO terms in the above mentioned categories, we hypothesize that Vienna-7 flies may have reduced fitness and competitiveness due to impaired response to light stimuli as a consequence of mass rearing in artificial conditions under low/artificial light, this impairment being reflected at the signaling (perception and signal transduction) and neuronal levels (responsive mechanism). Vienna-7 may also have reduced host and mate finding ability due to decreased chemical sensory development. In addition muscular development is diminished, reducing movement or flight ability in the flies as well as having potential impacts on longevity. As for irradiation effects, Pfam abundance clustering demonstrated the marked randomness of the irradiation effects, while few genes may be consistently affected by the treatment. This is not to say that irradiation does not have a deleterious effect on the fly, just that expression level changes are not consistent between replicate treatments. The study showed high induction of statistically differentially regulated genes in GO terms related to DNA repair mechanisms, demonstrating the DNA damage that occurs in the irradiated samples. Single and double stranded DNA damage caused by ionizing gamma radiation has been extensively reported in mammals [20-22], and is very likely one of the effects in flies. The data also showed that irradiation may somehow affect the presence of virus in pupae. One possible explanation of this is that the proportion of the population that is virus infected is weaker than other flies, and thus do not survive the impact of irradiation. In general, we can conclude that long-term artificial rearing of flies, added to the effect of ionizing radiation, may affect several specific pathways and biological processes in the fly, all of which may translate into reduced quality of individuals released for SIT.

Conclusions

The California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) reports a weekly release of approximately 125,000 sterile flies per square mile over more than 1,200 square miles by the USDA-CDFA Mediterranean Fruit Fly Exclusion Program, at an annual cost of approximately 15 million dollars for preventive purposes (http://www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/pdep/prpinfo/pg1.html). Under that perspective, it is highly desirable that the released sterile flies are of the best possible quality and with a high rate of competitiveness in the field. The basic principles under which current SIT methods are applied at this time (long term captivity and gamma irradiation) may limit its potential utility, and alternatives to SIT or modifications to it should be considered. One such potential approach involves transgenesis, a concept already tested in C. capitata through the insertion of a tetracycline-repressible transactivator [23-25], and in Olive fly (Bactrocera olea) with the use of a dominant, female-specific lethal genetic system [26]. Another alternative is population replacement. This method has been widely studied in the control mosquito-borne diseases with insects carrying anti-pathogen genes and thus unable to transmit disease [27]. Similar approaches could be utilized to produce only male progeny from mated females, and subsequent mating with these males will continue spreading this trait, effectively allowing the wild population to serve as the rearing mechanism. Additionally, in population replacement approaches, repeated mass release of flies would not be required, and the trait is pushed through the population. Those males carrying the trait are wild derived, and thus there is not expected to be a reduced fitness cost compared to flies derived from the wild population. As the International Atomic Energy Agency has expressed its interest in developing alternatives to gamma irradiation used for SIT programs [28], recent advances in gene silencing through RNAi methods should also be considered which could induce sterilization. These alternative approaches would have reduced impact on the quality of the fly as irradiation is not performed, which has been shown to impact courtship behavior. Overall, the analysis presented here provides the foundation for beginning to evaluate mass reared flies at a genomic level, and to develop tools for better monitoring the quality of these flies over generations of colony production.

Methods

Sampling of Ceratitis capitata Vienna-7 colony and Hawaiian wild fly

C. capitata Vienna-7 derived mass reared flies were obtained from the California Department of Agriculture medfly mass rearing facility in Waimanalo, Hawaii. Newly formed pupae were collected (~40 ml) in triplicate before irradiation. In addition, triplicate samples were subjected to gamma-irradiation at the USDA-APHIS irradiation facility (140 Gy) following the standard methods used for mass reared flies being shipped to California for SIT release. Both irradiated and non-irradiated flies were transferred to the USDA-ARS Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center (PBARC) for use in this study. Pools of five pupae were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen from each replicate approximately 1 day prior to adult emergence for RNA extraction and sequencing. A subset of pupae was placed in emergence cages and adult male flies were allowed to emerge. Adults were held in emergence cages under standard rearing conditions for 2 days post-emergence and then snap frozen in pools of five for each replicate. In addition, C. capitata infested coffee cherries were collected at Kauai Coffee (Kalaheo, HI, USA) and transferred to USDA-ARS-PBARC. Cherries were placed on a ¼ inch mesh screen elevated above sand in a fiberglass container, allowing C. capitata pre-pupae to emerge from the fruit and pupate in the sand. Pupae were allowed to develop until approximately 1 day prior to adult emergence. Sex of the pupae was determined by observing presence or absence of the spatulate bristle visible through the pupal cuticle. At this time, five male pupae for each replicate were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction. The remaining male pupae were put into adult emergence cages and adults were collected in the same manner as the Vienna line described above.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the triplicate samples from both pupal and adult stages of each treatment (wild, Vienna non-irradiated, and Vienna irradiated) using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufactures procedures with the following modifications. Approximately 30 – 50 mg of liquid nitrogen snap-frozen tissue was placed in 600 μl Buffer RLT with 1% β-mercaptoethanol and ground carefully with a disposable micropestle in a microfuge tube. This solution was then passed through a QIAshredder column and then through a gDNA Eliminator column. In addition, before final elution, on-column DNase treatments were performed to ensure full removal of genomic DNA from sample. RNA concentration and quality was assessed using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) as well as an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA) following standard protocols and assays.

Each of these total RNA samples was prepared for sequencing using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), barcoded, and all 18 libraries pooled and sequenced on a single lane of Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis (West Haven, CT, USA).

In silico library normalization and de novo transcriptome assembly

De novo reconstruction of the transcriptome was done utilizing the Trinity package [29]. Raw reads obtained were first normalized to reduce redundant read data and discard read errors using Trinity’s normalize_by_kmer_coverage.pl script with a kmer size of 25 and maximum read coverage of 30. The Trinity de novo RNAseq assembly pipeline (Inchworm, Chrysalis, and Butterfly) was executed using default parameters, implementing the --REDUCE flag in Butterfly and utilizing the Jellyfish k-mer counting approach [30]. Assembly was completed in 3 hours and 13 minutes on a compute node with 32 Xeon 3.1 GHz cpus and 256 GB of RAM on the USDA-ARS Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center Moana compute cluster (http://moana.dnsalias.org).

Assembly filtering and gene prediction

The output of the Trinity pipeline is a FASTA formatted file containing sequences defined as a set of transcripts, including alternatively spliced isoforms determined during graph reconstruction in the Butterfly step. These transcripts are grouped into gene components which represent multiple isoforms across a single unigene model. While many full length transcripts were expected to be present, it is likely that the assembly also consisted of erroneous contigs, partial transcript fragments, and non-coding RNA molecules. This collection of sequences was thus filtered to identify contigs containing full or near full length transcripts or likely coding regions and isoforms that are represented at a minimum level based off of read abundance. Pooled non-normalized reads were aligned to the unfiltered Trinity.fasta transcript file using bowtie 0.12.7 [31], through the alignReads.pl script distributed with Trinity. Abundance of each transcript was calculated using RSEM 1.2.0 (RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization) [32], utilizing the Trinity wrapper ‘run_RSEM.pl’. Through this wrapper, RSEM read abundance values were calculated on a per-isoform and per-unigene basis. In addition, percent composition of each transcript component of each unigene was calculated. From these results, the original assembly file produced by Trinity was filtered to remove transcripts that represent less than 5% of the RSEM based expression level of its parent unigene or transcripts with transcripts per million (TPM) value below 0.5.

Coding sequence was predicted from the filtered transcripts using the ‘transcripts_to_best_scoring_ORFs.pl’ script distributed with the Trinity software from both strands of the transcripts. This approach uses the software Transdecoder (http://transdecoder.sourceforge.net/) which first identifies the longest open reading frame (ORF) for each transcript and then uses the 500 longest ORFs to build a Markov model against a randomization of these ORFs to distinguish between coding and non-coding regions. This model is then used to score the likelihood of the longest ORFs in all of the transcripts, reporting only those putative ORFs which outscore the other reading frames. Thus, the low abundance filtered transcript assembly was split into contigs that contain complete open reading frames, contigs containing transcript fragments with predicted partial open reading frames, and contigs containing no ORF prediction. The resulting retained transcript sets containing transcripts above the abundance threshold and containing a likely open reading frame were merged and subjected to annotation and utilized in subsequent analysis.

Gene annotation

The filtered transcripts were annotated using the UniRef SwissProt database, Pfam-A, eggNOG, and gene ontology utilizing a beta release of the Trinotate annotation pipeline. The filtered transcript set was first subjected to blastp alignment against the UniRef-Swissprot database (downloaded 12/11/2012) using blast-2-2-26+ with e-value cutoff of 1.0E-5. In addition, protein domains were identified through searching the Pfam_A database using HMMER 3.0. Signal peptides and transmembrane regions were annotated with SignalP 4.1 and TMHMM 2.0, respectively. The resulting outputs were loaded into a Trinotate database where eggNOG and Gene Ontology terms were added and the resulting annotation set was exported as a delimited file for further analysis. In addition, transcripts were subjected to blastx alignment against the Drosophila melanogaster protein set (http://Flybase.org, Dmel-r5.44) [33,34] and UniRef90 using an e-value cutoff of 1e-5 to identify homologous genes in these databases.

Read library mapping and expression analysis

Because the Trinity assembler is able to accurately predict splice isoforms, gene and isoform expression quantification was performed using RSEM, which is particularly well suited to work with multiple isoforms where the same read may map to multiple sequences. The filtered transcript set described above (containing transcripts passing a minimum read abundance cutoff and containing predicted full or partial ORFs) was used for analysis to avoid skewing expression quantification results with non-coding and fragmented data. Reads from each sequencing library were independently mapped to this high confidence transcriptome assembly using bowtie (v 0.12.7) using the alignReads.pl script distributed with Trinity. The resulting bam formatted mapping files were sorted and used to produce fragment abundance estimation by RSEM. Transcript abundance values were produced as expected read count at both unigene and individual transcript isoform level.

Absolute expression analysis by Pfam

Read count values for unigenes were normalized using the trimmed mean of M values (TMM) method and transformed into fragments per feature kilobase per million reads mapped (FPKM) for each gene and the individual isoforms that compose each gene for each developmental library using scripts provided by Trinity. TMM-FPKM normalized read counts across genes in the same Pfam family were added together to assess family abundance. For clustering, Pfams with less than two gene members and normalized counts less than 50 in at least one library were removed. Pfams were clustered using Spearman rank correlation coefficients with complete linkage as distance measurement using Cluster v3.0 software [35,36]. Clusters were visualized in a heatmap using Java TreeView (http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net).

Differential expression analyses

Transcript abundance values were compared among samples using the EdgeR package (bioconductor) to assess statistical significance [37]. The general linear models capability (glm EdgeR) was used to account for the multiple factors in the experiment (i.e. colony, developmental stage and irradiation treatment). The non-normalized expected counts for each gene, calculated by RSEM in the previous step, were used as input for EdgeR; contrasts were built between the three main overall effects and between the six pairwise comparisons of biological relevance for a total of nine comparisons. The data was normalized between each pair of groups or samples with the TMM method using the calcNormFactors function to account for the effect of RNA composition. Out of the 10,775 genes identified, a total of 9,920 genes were used for differential analyses after filtering out genes with count per million mapped reads less than 2 in any of the three replicate samples.

Gene ontology term enrichment

The bioconductor package “topGO” was used to run a GO term enrichment analysis on the data [38]. Genes declared significantly differentially regulated on each of the treatment-wise comparisons and mapped with GO terms were used as predefined lists of genes of interest. Terms with less than 5 annotated genes were cut-out from the GO hierarchy during the enrichment using the nodSize option, and only the “biological processes” ontology was used. GO terms were then subjected to the classic Fisher’s exact test included in the topGO package.

Availability of supporting data

All raw reads were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers SAMN02208095 – SAMN02208112 associated with BioProject PRJNA208956.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SMG. Performed the experiments: SMG. Analyzed the data: BC, BH and SMG. Evaluated conclusions: BC, BH, SH and SMG. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: BC, BH, SH, and SMG. Wrote the paper: BC, BH, and SMG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Abundance of TMM normalized reads on each protein family.

Sub-cluster of identified Pfams derived from Figure 2. Differences between adults and pupae libraries across both types of flies. Subcluster shows Pfams with higuer abundance in the adult stage.

Sub-cluster of identified Pfams derived from Figure 2. Differences between adults and pupae libraries across both types of flies. Subcluster shows Pfams with higher abundance in pupae stage.

Top 30 enriched GO terms in adult vs. pupae.

Top 30 enriched GO terms in Irradiated vs. non-irradiated.

Top enriched GO terms in irradiated vs. non-irradiated Vienna7 pupae.

Top enriched GO terms in irradiated vs. non-irradiated Vienna7 adults.

Contributor Information

Bernarda Calla, Email: bernarda.calla@ars.usda.gov.

Brian Hall, Email: bhall7@hawaii.edu.

Shaobin Hou, Email: shaobin@hawaii.edu.

Scott M Geib, Email: scott.geib@ars.usda.gov.

AcknAcknowledgements

We thank Steven Tam for laboratory assistance; Song Min So at the CDFA Waimanalo medfly mass rearing facility for providing access to irradiated and non-irradiated Vienna line medfly; Kauai Coffee for providing infested coffee cherry for wild medfly collection; Yale Center for Genome Analysis for Illumina HiSeq services. This work was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS). Opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

References

- De Meyer M, Robertson MP, Peterson AT, Mansell MW. Ecological niches and potential geographical distributions of Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) and Natal fruit fly (Ceratitis rosa) J Biogeogr. 2008;15(2):270–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mediterranean Fruit Fly. http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/fruit/mediterranean_fruit_fly.htm.

- Vargas RL, Harris EJ, Nishida T. Distribution and seasonal occurrence of ceratitis capitata (wiedemann) (diptera: tephritidae) on the island of kauai in the hawaiian islands. Environ Entomol. 1983;15(2):303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos NT, Plant RE, Carey JR. From trickle to flood: the large-scale, cryptic invasion of California by tropical fruit flies. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2013;15(1768) doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz G, Gencheva E, Kerremans P. Improved stability of genetic sex-separation strains for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Genome. 1994;15(1):72–82. doi: 10.1139/g94-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerremans P, Franz G. Isolation and cytogenetic analyses of genetic sexing strains for the medfly, Ceratitis capitata. Theoret Appl Genetics. 1995;15(2):255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00220886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AS, Cirio U, Hooper GHS, Capparella M. Field cage studies with a genetic sexing strain in the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Entomol Exp Appl. 1986;15(3):231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1986.tb00533.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franz G, Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS. Sterile Insect Technique. Netherlands: Springer; 2005. Genetic sexing strains in mediterranean fruit fly, an example for other species amenable to large-scale rearing for the sterile insect technique; pp. 427–451. [Google Scholar]

- Lance DR, McInnis DO, Rendon P, Jackson CG. Courtship among sterile and wild ceratitis capitata (diptera: tephritidae) in field cages in hawaii and guatemala. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2000;15(5):1179–1185. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746(2000)093[1179:CASAWC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelly TE, Whittier TS, Kaneshiro KY. Sterile insect release and the natural mating system of the mediterranean fruit Fly, ceratitis capitata (diptera: tephritidae) Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1994;15(4):470–481. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza HML, Matioli SR, de Souza WN. The adaptation process of Ceratitis capitata to the laboratory analysis of life-history traits. Entomol Exp Appl. 1988;15(3):195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1988.tb01180.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henter HJ. Inbreeding depression and haplodiploidy: experimental measures in a parasitoid and comparisons across diploid and haplodiploid insect taxa. Evolution. 2003;15(8):1793–1803. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriwada T, Kumano N, Shiromoto K, Haraguchi D. Effect of mass rearing on life history traits and inbreeding depression in the sweetpotato weevil (coleoptera: brentidae) J Econ Entomol. 2010;15(4):1144–1148. doi: 10.1603/EC09361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist AS, Cameron EC, Sved JA, Meats AW. Genetic consequences of domestication and mass rearing of pest fruit Fly bactrocera tryoni (diptera: tephritidae) J Econ Entomol. 2012;15(3):1051–1056. doi: 10.1603/EC11421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgakova NA, Klapholz B, Brown NH. Cell adhesion in drosophila: versatility of cadherin and integrin complexes during development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;15(5):702–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg C-P, Fässler R. Cell–cell adhesion and extracellular matrix: diversity counts. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;15(5):559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huszar T, Imler JL. Drosophila viruses and the study of antiviral host-defense. Advances in virus research. 2008;15:227–265. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plus N, Veyrunes JC, Cavalloro R. Endogenous viruses of ceratitis capitata wied. «J. R. C. Ispra strain, and of C. Capitata permanent cell lines. Ann Inst Pasteur Virol. 1981;15(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/S0769-2617(81)80057-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terzian C, Ferraz C, Demaille J, Bucheton A. Evolution of the gypsy endogenous retrovirus in the drosophila melanogaster subgroup. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;15(6):908–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulston M, Fulford J, Jenner T, de Lara C, O’Neill P. Clustered DNA damage induced by γ radiation in human fibroblasts (HF19), hamster (V79‒4) cells and plasmid DNA is revealed as Fpg and Nth sensitive sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;15(15):3464–3472. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikjoo H, O’Neill P, Wilson WE, Goodhead DT. Computational approach for determining the spectrum of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2001;15(5):577–583. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0577:CAFDTS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oneill P, Fielden EM. Primary free-radical processes in dna. Adv Radiat Biol. 1993;15:53–120. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari OS, Matzen Kelly D, Marshall John M, Huang H, Ward Catherine M, Hay Bruce A. A synthetic gene drive system for local, reversible modification and suppression of insect populations. Curr Biol. 2013;15(8):671–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CM, Su JT, Huang Y, Lloyd AL, Gould F, Hay BA. Medea selfish genetic elements as tools for altering traits of wild populations: a theoretical analysis. Evolution. 2011;15(4):1149–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM, Hay BA. Confinement of gene drive systems to local populations: a comparative analysis. J Theor Biol. 2012;15:153–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ant T, Koukidou M, Rempoulakis P, Gong H-F, Economopoulos A, Vontas J, Alphey L. Control of the olive fruit fly using genetics-enhanced sterile insect technique. BMC Biol. 2012;15(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. The effect of gene drive on containment of transgenic mosquitoes. J Theor Biol. 2009;15(2):250–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency IAE. 56th IAEA Annual Conference: 2012. Vienna, Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency; 2012. Developing Alternatives to Gamma Irradiation for the Sterile Insect Technique - NTR 2012 Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotech. 2011;15(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marçais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;15(6):764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg S. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;15(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey C. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinforma. 2011;15(1):323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Pierre SE, Ponting L, Stefancsik R, McQuilton P, Consortium tF. FlyBase 102—advanced approaches to interrogating FlyBase. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;15(D1):D780–D788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marygold SJ, Leyland PC, Seal RL, Goodman JL, Thurmond J, Strelets VB, Wilson RJ. Consortium tF: FlyBase: improvements to the bibliography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;15(D1):D751–D757. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hoon MJL, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;15(9):1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch A, Eisen M. Exploring the conditional coregulation of yeast gene expression through fuzzy k-means clustering. Genome Biol. 2002;15(11):research0059. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-11-research0059. 0051–research0059.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]